#2010s ebola outbreak

Text

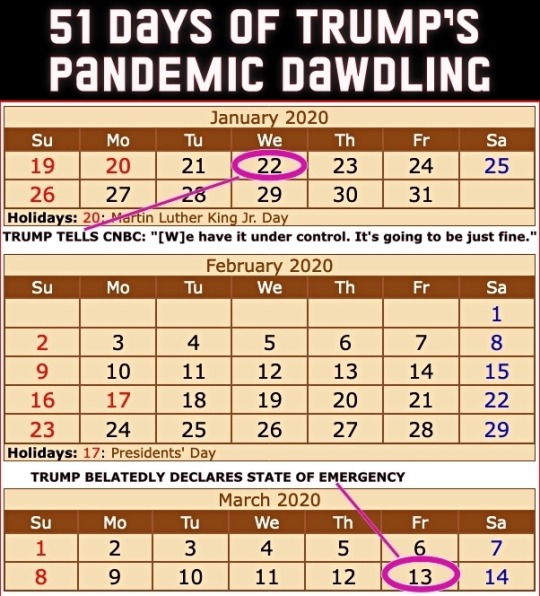

Four years ago today (March 13th), then President Donald Trump got around to declaring a national state of emergency for the COVID-19 pandemic. The administration had been downplaying the danger to the United States for 51 days since the first US infection was confirmed on January 22nd.

From an ABC News article dated 25 February 2020...

CDC warns Americans of 'significant disruption' from coronavirus

Until now, health officials said they'd hoped to prevent community spread in the United States. But following community transmissions in Italy, Iran and South Korea, health officials believe the virus may not be able to be contained at the border and that Americans should prepare for a "significant disruption."

This comes in contrast to statements from the Trump administration. Acting Department of Homeland Security Secretary Chad Wolf said Tuesday the threat to the United States from coronavirus "remains low," despite the White House seeking $1.25 billion in emergency funding to combat the virus. Larry Kudlow, director of the National Economic Council, told CNBC’s Kelly Evans on “The Exchange” Tuesday evening, "We have contained the virus very well here in the U.S."

[ ... ]

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi called the request "long overdue and completely inadequate to the scale of this emergency." She also accused President Trump of leaving "critical positions in charge of managing pandemics at the National Security Council and the Department of Homeland Security vacant."

"The president's most recent budget called for slashing funding for the Centers for Disease Control, which is on the front lines of this emergency. And now, he is compounding our vulnerabilities by seeking to ransack funds still needed to keep Ebola in check," Pelosi said in a statement Tuesday morning. "Our state and local governments need serious funding to be ready to respond effectively to any outbreak in the United States. The president should not be raiding money that Congress has appropriated for other life-or-death public health priorities."

She added that lawmakers in the House of Representatives "will swiftly advance a strong, strategic funding package that fully addresses the scale and seriousness of this public health crisis."

Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer also called the Trump administration's request "too little too late."

"That President Trump is trying to steal funds dedicated to fight Ebola -- which is still considered an epidemic in the Democratic Republic of the Congo -- is indicative of his towering incompetence and further proof that he and his administration aren't taking the coronavirus crisis as seriously as they need to be," Schumer said in a statement.

A reminder that Trump had been leaving many positions vacant – part of a Republican strategy to undermine the federal government.

Here's a picture from that ABC piece from a nearly empty restaurant in San Francisco's Chinatown. The screen displays a Trump tweet still downplaying COVID-19 with him seeming more concerned about the effect of the Dow Jones on his re-election bid.

People were not buying Trump's claims but they were buying PPE.

I took this picture at CVS on February 26th that year.

The stock market which Trump in his February tweet claimed looked "very good" was tanking on March 12th – the day before his state of emergency declaration.

Trump succeeded in sending the US economy into recession much faster than George W. Bush did at the end of his term – quite a feat!. (As an aside, every recession in the US since 1981 has been triggered by Republican presidents.)

Of course Trump never stopped trying to downplay the pandemic nor did he ever take responsibility for it. The US ended up with the highest per capita death rate of any technologically advanced country.

Precious time was lost while Trump dawdled. Orange on this map indicates COVID infections while red indicates COVID deaths. At the time Trump declared a state of emergency, the virus had already spread to 49 states.

The United States could have done far better and it had the tools to do so.

The Obama administration had limited the number of US cases of Ebola to under one dozen during that pandemic in the 2010s. Based on their success, they compiled a guide on how the federal government could limit future pandemics.

Obama team left pandemic playbook for Trump administration, officials confirm

Of course Trump ignored it.

Unlike those boxes of nuclear secrets in Trump's bathroom, the Obama pandemic limitation document is not classified. Anybody can read it – even if Trump didn't. This copy comes from the Stanford University Libraries.

TOWARDS EPIDEMIC PREDICTION: FEDERAL EFFORTS AND OPPORTUNITIES IN OUTBREAK MODELING

Feel free to share this post with anybody who still feels nostalgic about the Trump White House years!

#covid-19#coronavirus#pandemic#public health#donald trump#trump's incompetent response to the pandemic#covid state of emergency#2020#trump recession#51 days of trump pandemic dawdling#obama pandemic playbook#2010s ebola outbreak#nostalgia for trump administration#republicans#election 2024#vote blue no matter who

108 notes

·

View notes

Text

Take the southwest corner of the West African nation of Guinea. One of the world's most biodiverse forests once covered the region. Large tracts of underdeveloped forests, being difficult for people to penetrate, had limited contact between forest animals and humans. Wild animals could live in the forest without encountering humans or human settlements.

That changed during the 1990s, as the Guinean forest was steadily destroyed. A wave of refugees descended upon the forest to escape a long, blood, complex conflict between armies and rebel groups from neighboring Sierra Leone and Liberia. (At first they'd tried to settle in refugee camps in the forest area's central town of Guéckédou, but rebel groups and government soldiers repeatedly attacked their camps.)

The refugees cut down trees to plant crops, build huts, and turn into charcoal. Rebel groups started logging the forest, too, selling timber to finance their battles. By the end of the 1990s, the transformation of the forest could be seen from space. In satellite images from the mid-1970s, the jungles in Guinea bordering Libera and Sierra Leone looked like a sea of green splattered with tiny islands of brown, where small clearings had been made for villages. Satellite images from 1999 showed a complete reversal: a sea of treeless brown, with tiny islands of green forest speckled in between. Of the entire region's original forests, only 15 percent remained.

Just how this wide-scale deforestation affected the forest ecosystem has yet to be fully described. Many species that lived in the forest probably just disappeared when humans moved into their habitats. What is known is that some species stayed. They squeezed in, resorting to smaller patches of remaining stands of trees, in increasing proximity to human habitations.

Bats were among them. It stands to reason: bats are widely distributed and resilient creatures. Of 4,600 species of mammals on earth, 20 percent are bats. And, as a study in Paraguay found, certain bat species thrive in disturbed forests in even higher abundances than in intact ones. Unfortunately, bats are also good incubators for microbes that can infect humans. They live in giant colonies of millions of individuals. Some species, like the little brown bat, can survive for as long as thirty-five years. And they have unusual immune systems. For example, because their bones are hollow, like those of birds, they don't produce immune cells in their bone marrow like the rest of us mammals do. As a result, bats host a wide range of unique microbes that are exotic to other mammals. And they travel around with these microbes over significant distances, because bats can fly. Some even migrate, traveling thousands of miles at a time.

As the Guinean forest was chopped down, new kinds of collisions between bats and people likely occurred. Bats were hunted for meat, exposing hunters to microbe-laden bat tissue when the animals were slaughtered. Bats fed on fruit trees near human settlements, exposing local people to their saliva and excreta. (Fruit bats are notoriously messy eaters; their modus operandi is to pick off ripe fruit and suck out the juice, littering the ground below with saliva-covered, half-eaten fruits.)

At some point – nobody knows just when – a microbe of bats, the filovirus Ebola, started to spill over and infect people. In humans, Ebola causes hemorrhagic fever and can kill 90 percent of those it infects. A study of blood samples collected from people in eastern Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Guinea between 2006 and 2008 revealed that nearly 9 percent had been exposed to Ebola: their immune systems had created specific proteins called antibodies in response to the virus. A 2010 study of over four thousand people in rural Gabon, where there'd been no outbreaks of Ebola, similarly found that nearly 20 percent had been exposed to the virus.

But nobody noticed. The ongoing conflict had severed supply routes and communication networks, leaving the refugees hiding in the jungle bereft of outside help. Even the most stalwart aid organizations such as Médecins Sans Frontières had been forced to withdraw. The isolation coupled with the violence compelled the United Nations to call the West African refugees' plight “the worst humanitarian crisis in the world.”

It wasn't until the political violence eased, in 2003, and the people hiding in the Guinean forest slowly reconnected with the rest of the world that the virus's presence became apparent. On December 6, 2013, Ebola virus sickened and killed a two-year-old child in a small forest village outside Guéckédou. Perhaps the toddler had played with a piece of fruit covered with bat saliva, fallen from a nearby tree. Perhaps the parents had been handling a recently slaughtered bat before picking up the child. It was probably not the first time someone in the Guéckédou area had encountered Ebola virus from a local bat. But this time, the people of Guéckédou were no longer as isolated as they'd been in the past. The virus was able to spread.

— Pandemic: Tracking Contagions, from Cholera to Ebola and Beyond (Sonia Shah)

#sonia shah#pandemic: tracking contagions from cholera to ebola and beyond#science#virology#epidemiology#ecology#deforestation#animals#zoology#warfare#refugees#sierra leone civil war#guinea#sierra leone#liberia#ebola#bats

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

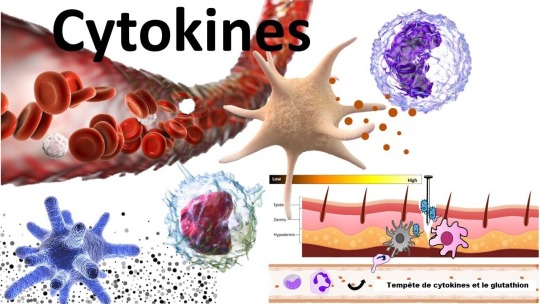

La tempête de cytokines – rôle des antioxydants et du glutathion

L’une des questions les plus fréquemment posées que j’ai reçues ces derniers jours concerne la tempête de cytokines et si l’effet du glutathion sur le système immunitaire joue un rôle positif ou négatif. Excellente question!

QU'EST-CE QUE LA "TEMPÊTE DE CYTOKINES"?

Je vais simplifier ici.

Le système immunitaire communique à travers diverses molécules de signalisation. Un groupe majeur de ces agents biochimiques s’appelle «cytokines». Elles peuvent envoyer des signaux pour augmenter l'activité immunitaire, pour baisser l'activité immunitaire, pour augmenter l'inflammation ou pour la diminuer. Les cytokines qui augmentent l'inflammation sont appelées «cytokines inflammatoires».

Certaines conditions, y compris diverses infections virales sévères (grippe, coronavirus, Ebola), entraînent une surproduction de cytokines inflammatoires. Elles sont destinées à endommager et détruire le virus, mais les choses peuvent dégénérer et elles commencent à endommager les tissus "normaux" également, comme le poumon. Cela peut se transformer en conditions plus graves comme le SRAS (syndrome de détresse respiratoire aiguë) et la mort.

COMMENT CELA EST-IL LIÉ AU STRESS OXYDATIF?

Une grande partie de l'inflammation passe par la libération de radicaux libres et d'autres substances hautement oxydatives. C'est pourquoi les niveaux de glutathion et d'autres antioxydants sont bas dans ces conditions.

EXISTE-T-IL DES ARTICLES DE RECHERCHE OÙ LES ANTIOXYDANTS ONT ÉTÉ UTILISÉS POUR COMBATTRE LA TEMPÊTE DE CYTOKINES?

Certainement. J'ai répertorié ci-dessous quelques articles. Certains antioxydants qui ont été étudiés incluent le NAC (qui augmente le glutathion), le resvératrol et la vitamine C. Rappelons que le glutathion est l'antioxydant "maître".

RÉFÉRENCES

La tempête de cytokines de la grippe sévère et le développement de la thérapie immunomodulatrice.

Geiler J, Michaelis M, Naczk P, Leutz A, Langer K, Doerr HW. N-acétyl-L-cystéine (NAC) inhibe la réplication du virus et l'expression de molécules pro-inflammatoires dans les cellules A549 infectées par le virus de la grippe A H5N1 hautement pathogène. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010; 79:413–420.

Médicaments pour guérir l'infection par la grippe aviaire-- plusieurs façons de prévenir la mort cellulaire.

Le rôle de l'acide ascorbique dans la maîtrise de la pandémie mondiale de la grippe aviaire. Ely JT Exp Biol Med (Maywood). Juil. 2007; 232(7):847-51.

L'expression de Nrf2 modifie l'entrée et la réplication du virus de la grippe A dans les cellules épithéliales nasales. Kesic MJ, Simmons SO, Bauer R, Jaspers I Free Radic Biol Med. 15 Juil. 2011; 51(2):444-53.

Inhibition de la réplication du virus de la grippe A par le resvératrol. Palamara AT, Nencioni L, Aquilano K, De Chiara G, Hernandez L, Cozzolino F, Ciriolo MR, Garaci E J Infect Dis. 15 Mai 2005; 191(10):1719-29.

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Text

Born April 25, 1994, Kerkula Blama alias Aketella is Liberian blogger, vlogger, On-Air Personality, singer, song writer and influencer.

Aketella has been into blogging since 2016. He started off with one of Liberia’s biggest music platforms PlusLiberia from 2016 up till 2018 when he saw it necessary to establish his own platform, Geez Liberia formerly called LIB Geez.

Before then, the name and idea of the mother company Geez Group Of Companies has been in mind and Geez Liberia only become a cooperation of that company. Alongside Geez Liberia are blogs and other smaller cooperation and companies such as Geez Salone, Geez Nigeria, Geez Ghana, Geez Sports, Geez Store and AME University Geez.

These platforms have been in the African Entertainment sectors for years and have made significant impact on shaping the society positively and efficiently.

Full Profile of Kerkula Aketella Blama:

Name: Kerkula Aketella Blama.

Born: April 25, 1994

Place of Birth: Salala, Bong County

Career: Blogger, Vlogger, On-Air Personality, Singer and Song Writer.

Kerkula Aketella Blama is a Liberian blogger, singer, song writer, vlogger and On-Air Personality born unto the union of Mr. and Mrs. Alphonso Blama in Salala Bong County.

Aketella as he is commonly known as grew up in the Snow Hill community Gardenersville where he started his primary education at the St. Phillip Elementary and Junior high school. Prior to life in Monrovia, Aketella was raised by his parents in Salala Bing County amidst the heated 1990 - 2013 civil crisis that was still ongoing in the country.

From Monrovia, his family later moved to the Firestone Rubber Plantation in 2004 where he began attending the Firestone School System; precisely the Division 14 Elementary School. Upon his graduation from elementary school he continued his studies at the Division 16 junior high school another Firestone School System school.

He graduated from Junior High school in 2010 and had to move to Harbel to live and study at the only high school in the plantation; The Firestone Liberia Senior High School.

In 2015, Aketella was amongst the 700 and more students who passed the WASSCE and all the courses prescribed in his school’s curriculum certifying him to become a graduate thereby acquiring a Diploma from the school in 2015. But because of the outbreak of EBOLA the graduation ceremony of which he was to be a part of, was delayed and postponed to 2016.

Kerkula Aketella Blama is currently a student at the African Methodist Episcopal University studying Management Major and Public Administration Minor, and also serving as the CEO and Founder of Geez Liberia, Geez Ghana, Geez Nigeria, Geez Sports, Geez Store and AME University Geez which are all a cooperation of Geez Group of Companies of which he is also the CEO/Founder of.

You can follow Aketella on all social media platforms by hitting these links.

Facebook:

https://facebook.com/aketellaoffcial

Instagram:

https://instagram.com/Aketella

Twitter:

https://twitter.com/_aketella

1 note

·

View note

Text

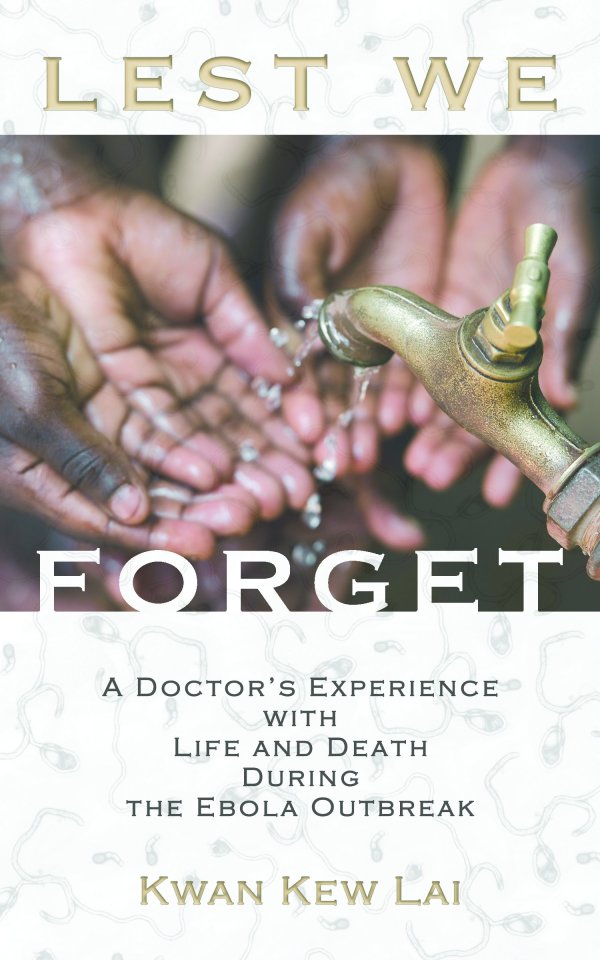

Wellesley Writes It: Interview with Kwan Kew Lai ’74 (@KwanKew), infectious disease physician & author of LEST WE FORGET: A DOCTOR’S EXPERIENCE WITH LIFE AND DEATH DURING THE EBOLA OUTBREAK

Kwan Kew Lai ’74, M.D., D.M.D., is an infectious disease specialist who has volunteered her medical services all over the world and the author of Lest We Forget: A Doctor’s Experience with Life and Death During the Ebola Outbreak. In 2004, after the Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami, she spent three weeks in India, caring for survivors. She soon left her position as a full-time Professor of Medicine in Infectious Diseases and Internal Medicine at UMass Memorial Medical Center and created a half-time position as a clinician, dedicating the other half of her time to humanitarian work.

Since 2005, Lai has volunteered as a mentor to health workers addressing the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Vietnam, Tanzania, Uganda, South Africa, Nigeria, Malawi and has provided earthquake relief in Haiti and Nepal, hurricane relief in the Philippines and drought and famine relief in Kenya and the Somalian border. She has also worked with refugees of the Democratic Republic of Congo and internally displaced people in Libya during the Arab Spring and South Sudan after the civil war and treated Ebola patients in Liberia and Sierra Leone. Most recently, she served as a medical volunteer in the Syrian refugee camps in mainland Greece and in Moria refugee camp on Lesvos, Greece for refugees from Syria, Afghanistan, Iran and the countries of the Sub-Saharan Africa and in the world’s biggest refugee camps for the Rohingya in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. Lai has blogged extensively about her experiences.

Originally from Penang, Malaysia, Lai came to the United States after receiving a scholarship to attend Wellesley, where she studied molecular biology. “Without that open door I would not have gone on to become a doctor,” Lai wrote in her Doctors Without Borders bio.

Lai has received numerous awards for her work, which include being a three-time recipient of the President’s Volunteer Service Award. In 2017, she was awarded Wellesley College Alumnae Achievement Award. In addition, Lai is the lead author of many publications and presentations. Her research has included HIV studies, infection control, hospital epidemiology, and antibiotic trials. She has served on many committees, task forces, and boards, including the Governor’s Advisory Board for the Elimination of Tuberculosis in Massachusetts. She is also an avid marathon runner and paints when she is inspired.

Wellesley Underground’s Wellesley Writes it Series Editor, E.B. Bartels ’10, had the chance to converse with Lai via email about Lest We Forget and about her experiences at Wellesley and beyond. E.B. would also like to make note that Lai made time to answer these questions even while busy with her 45th Wellesley Reunion!

EB: How did Lest We Forget come about? What inspired you to write the book?

KKL: I first became aware of the Ebola outbreak in March of 2014, I began to follow it very closely. I read about Ebola when I was in my training as an infectious disease specialist. It is a deadly viral infection but it usually occurs in Africa and I knew that it would be unlikely for me to see a patient with this infection. In the summer of 2014 when WHO finally acknowledged the seriousness of the situation, the nightly TV images of people desperate to get into a hospital and bodies lying in the streets because they were too infectious to be touched, moved me. I knew I had to be in West Africa to volunteer.

I started blogging a few years ago when I went to volunteer to enable my family and close friends to keep abreast of my situation and so I did the same when I started volunteering in the Ebola Treatment Unit (ETU). Deeper into my volunteering I was very moved by the courage and resilience of the patients and the dedication and dogged determination of the people who worked alongside me and who risked their lives working in the frontline. After my first stint in West Africa, I was interviewed by NPR international health correspondent, Nurith Aizenman, about my experience and she had urged me to write a book. I had thought about that as well before she brought it up but I was too taken up into my second stint of Ebola volunteer by then. When I was in Sierra Leone doing my second Ebola volunteering, I was also contacted by an agency who wanted to represent me with either writing a book or making a documentary. However just before I left for Sierra Leone, I signed with my first agent about my book on Africa which is about my experiences as a volunteered doctor in HIV/AIDS and my work in the refugee camps. I did not feel it was ethically right to deal with another agency. Nevertheless, writing a book about Ebola became more urgent, I wanted to write this in honor and memory of the people afflicted by Ebola and the frontline bola fighters who put their lives on the line. It took me awhile for me to convince my agent to present my book on Ebola first before my book on Africa.

EB: Lest We Forget is a work of nonfiction and, not only that, a book about a very intense topic. What was challenging about writing about that subject? What kept you wanting to write the book, even if it was difficult? And how did you handle writing about people's personal experiences, especially when dealing with sensitive medical information?

KKL: Keeping a daily blog helped to lighten the burden of writing about the trauma of the people all at once. The blog became my fact book that I could go back to if I did forget an event or a person. As I stated before, the book was written as a tribute to the people I wanted to honor and remember, that helped the process a great deal. I changed the names of the people as much as I could to preserve confidentiality. Keeping a blog daily also provided me an emotional catharsis while volunteering in the ETU. I also wanted to rejoice with the people who recovered from this grave illness.

EB: Is Lest We Forget is your first book? What was challenging about writing it, and what was rewarding about the process?

KKL: No, it is not my first book. In February 2014, I signed with an agent for my Africa book which I had been writing for a couple of years before Lest We Forget, which is about my volunteering experiences in Africa. Before then I attempted to write a book, a sort of coming-of-age story for my children, this has not been presented to anyone. My years of writing on my own have taught me that I still have a lot of work on that book and it would have to go through many more draughts. Keeping a blog or diary helps with one’s writing. Reading a lot and writing, both help with my writing.

I also learned a lot through trying to find an agent or publisher for my book, if there is no market for the topic of one’s book, it will not likely to be accepted by either. My book on Africa, tentatively titled, Into Africa: A Journey from Academic Medicine to Bush Medicine has been accepted a few months ago for publication next year, I found a publisher without the help of my agent. It will now go through many months of work with the editors, etc. before the actual date of publication. I was told nine to fifteen months from May.

EB: What advice would you give to someone writing a book? Perhaps someone also writing a nonfiction book about an intense topic?

KKL: Writing and rewriting many times over. Keep a blog on your experiences, despite the intensity, you would be surprised how your mind works to block the painful parts of the experiences. If you have some willing readers, it may be helpful to let others read your draughts.

EB: In addition to your work as an infectious disease specialist, have you always enjoyed writing? Did you write at all before this book? Did you study writing while you were at Wellesley?

KKL: As a professor of medicine, I presented in national and international conferences, wrote and published many scientific papers, and a few medical essays. As foreign students, we were all required to take a course in English as second language during our first year, I did not find this very helpful but it was required. In my junior year, I took a writing course in which we were required to write and critique each other’s writings. We met once a week at the professor’s home. I did not find this helpful either. It seemed quite subjective and I think it was an easy course for the professor who I think did not offer helpful advice on our writing. I find scientific writings tend to be precise, cut and dry, very different from creative writing and as my background is in science, I have a great deal to learn.

EB: How did your time at Wellesley influence you and your career path, if at all?

KKL: I was more influenced by what I read during my teenage years. Wellesley provided a safe and secure place for me to grow. Coming from an Asian background, we are not taught to seek guidance and friendship from the professors, they are often put on the pedestal to revere and not as someone you could seek advice, reveal your vulnerabilities, or share your ambitions with. In my later years, I’m often jealous of Wellesley classmates who kept up friendship with their professors after they left college. My foreign student advisor at Wellesley advised me not to apply to medical schools because many excellent foreign students in the past did not get admitted and that I should apply to other allied health professions instead. I was accepted at the Harvard School of Dental Medicine after my junior year but I realized that Medicine was still my first love and after my dental degree I went back to medical school.

EB: Who at Wellesley made the biggest impact on you and your career? Faculty, staff, fellow students? Which particular individuals?

KKL: As I expressed above, I wished I was freer in finding advisors in my professors. Jeanette McPherrin, who became the Dean of Foreign Students during my last years at Wellesley, will always be remembered by me as a friend who kept up a correspondence with me until she passed. I found her to be non-judgmental, genuinely kind, and interested in all foreign students as individuals.

The biggest impact for me was when Wellesley College offered me a full scholarship, this gave me the opportunity to get an education and fulfil my ambition to be a doctor. I remember being inspired by Dr. Tom Dooley and Dr. Albert Schweitzer who went to underdeveloped countries to provide medical care and Wellesley College’s motto of non ministrari sed ministare also spur me on to pay it forward.

EB: What else would you like our readers to know about you and/or your work?

KKL: I currently live in Belmont, MA and have three children. Last week, I received a letter from the Dean of my medical school that they have selected me to receive their Distinguished Alumnus Service Award in October 2019.

EB: That’s wonderful! Congratulations!

#wellesley#wellesley college#wellesley underground#wellesley writes it#wu#class of 1974#wellesley '74#kwan kew lai#e.b. bartels#eb bartels#class of 2010#wellesley '10#lest we forget#ebola#ebola outbreak#wellesley writes it series

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've been around for a bit, I'm creeping up on 52, but I don't recall the death totals for anything not resetting yearly. I think I've pointed this out before, but it's worth pointing out again.

1977-1980 The last known case of smallpox, a viral disease that plagued humans for millennia, is diagnosed in 1977 in Somalia.

1981- to present 1981 report by what is now the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) describes a rare form of pneumonia that is later identified as Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome, or AIDS. It is the most advanced stage of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV).

2002-2003 The Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) coronavirus, part of a family of viruses that commonly cause respiratory symptoms such as coughing and shortness of breath, is first identified in late 2002 in southern China.

2009-2010 A new influenza virus, labeled H1N1 and commonly referred to as the swine flu because of its links to influenza viruses that circulate in pigs, begins to spread in early 2009 in Mexico and the United States. Unlike other strains of influenza, H1N1 disproportionately affects children and younger people. The CDC calls it the “first global flu pandemic in forty years.”

2012 A new coronavirus, named Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), is transmitted to humans from camels in 2012 in Saudi Arabia. The largest outbreak occurs on the Arabian Peninsula in the first half of 2014, with the Saudi city of Jeddah as its epicenter.

2014-2016 In early 2014, cases of the Ebola virus, a rare and severe infectious disease that leads to death in roughly half of those who contract it, are detected in Guinea and soon after in Liberia and Sierra Leone. It is the first time the disease moves into densely populated urban areas, allowing for rapid transmission.

2015-2016 An outbreak of the Zika virus, first discovered in Uganda in the 1940s and transmitted mainly by mosquitoes, takes off in Brazil in early 2015. In February 2016, the WHO declares the outbreak a PHEIC, and by the middle of the year more than sixty countries report cases of the virus, including the United States.

Side Note:

2005 The WHO rewrites its International Health Regulations, rules originally drawn up in 1969 that are binding on all WHO member states. The new rules aim to boost collective defenses against global health challenges and improve pandemic preparedness and response. Entering into force in June 2007, they require states to notify the WHO of potential global health emergencies. They also grant the WHO director-general the authority to declare a public health emergency of international concern, or PHEIC, in order to mobilize a global response. The changes are meant to build on the GOARN established in 2000.

There are two reasons why everything but CoVID illnesses and deaths reset every year, control and fear.

The number has to look way worse by keeping the number inflated. If it reset every year there would not be that WOW factor of so many deaths. We would be able to see if the totals fall or rise each year we'd be able to think for our selves.

In the same time, late 2019 to now, 1,665,500 +/- people have died from heart disease (The #1 cause of death in the US.), 1,499,000 +/- people died from cancer, 432,500 +/- from accidents, and 390,000 +/- from Chronic lower respiratory diseases (chronic bronchitis, emphysema, and asthma).

The crazy thing is, most of those deaths over the last 2 ½ years were preventable. If the “Gooberment” put CoVID type effort into solving the top 4 reasons for death in the US more people would be alive today.

The government doesn’t want US to see that preventable death are killing us faster than CoVID. They don’t want you to see that broken down, CoVID is much less impactful that the top two reasons that kill our population by far.

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

Iris Publishers - World Journal of Yoga, Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation (WJYPR)

Global Health: Global Infectious Disease Control Systems

Authored by Shinu Kuriakose

Introduction

The fundamental issue concerning global healthcare policy is the recognition of the role various institutions, including nongovernmental agencies and countries, play to mitigate the spread of diseases and other pathological factors to prevent global morbidity and mortality. It is inherent that the role of not only screening, reporting, diagnosing and treating illness, with a potential to be a pandemic, be have clear command and control protocols but also timeliness and efficiency of this process is crucial. Poverty, maternal and child illnesses, disease prevention, vaccinations, and the paucity of food and water do play a crucial role for entities while framing foreign policy and regulations. The concept of rapid response to diseases, such as Ebola recently, can help reduce the number of casualties in a given population and furthermore help halt the spread of illness. It is the responsibility of the both the public and private sector to implement procedures in a manner with the understanding that a failure on their part could lead to disastrous consequences; a fact which lends itself to the recognition that the world is increasingly inter-connected and an ill person can just as easily spread a disease in New York, due to the immediacy and availability of air transport as h/she can spread it in their neighboring village in Asia.

The Oslo Declaration in 2010, signed by the foreign ministers of seven countries, has in its core the concept of how any proposed policy will affect healthcare in the region and important consideration must also be given to economic consequence of healthcare reform, collaboration between parties and the implementation of healthcare protection to provide sound medical protection on a global scale. Furthermore, The Disease Control Priorities Project (DCP2), in 2006, has attempted to formulate questions and responses a country must ask itself to assess its preparedness for an health outbreak; a process which takes into consideration the universal definition of a disease, the effectiveness and response to this malady, the priorities which need to be considered in rank order, the interventions which need to be implemented to achieve said objectives, the importance of cost-effective processes taking into consideration equitable health care with a focus on reducing disparities, preventative strategies focusing on food and water safety, vaccination and immunization protocols and effective sanitation and educational programs [1].

Discussion

World health organization

The World Health Organization is a part of the United Nations, founded in 1948, with a specific focus and emphasis on public health internationally. This organization is currently focused on the eradicating of communicable diseases such as Ebola, HIV and TB and has been successful in the elimination of smallpox [2]. WHO characterizes diseases into categories such as communicable (viral or bacterial), non-communicable (obesity and mental health and injuries (accidental or natural disasters) [3]. WHO’s priorities include supporting its member states in preparing their singular capacities to deal with epidemics and ensuring that enough warning systems are in place to screen for pathologies including laboratory facilities, implementing training programs for epidemic readiness, coordination among its members to deal with any pandemics and seasonal influenza, ensuring uniform protocols are in place to standardize both screening and treatment techniques and minting a ready stance to deal with any major outbreaks and providing support in the healthcare realm to its constituents [4].

In the recent Ebola outbreak, WHO played a pivotal role in the initial screening and understanding of this disease by sending its epidemiologists and health promotion officers, in early June 2014, to countries in West Africa where reports were emerging of a viral disease with lethal consequences. Its medical team had to track this illness to its source and look at the cumulative data from laboratories, patients, providers and hospitals to gain a better understanding of their healthcare adversary. Furthermore, WHO took the lead in preventing transmission of this disease by identifying folks with this illness, treating patients with Ebola, conducting safe burials and being the lead in prevention of spread of Ebola. Additionally, it attempted to halt the spread of Ebola in unaffected countries, deployed rapid response teams for new outbreaks, helped prepare unaffected countries in case of an outbreak, helped with infrastructure to isolate patients with this illness, helped develop rapid screening and treatment modalities and put resources in for research purposes in the realms of vaccinations for this disease [5].

Centers for disease control and prevention

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), founded in 1946, is the leading federal agency of the United States government, under the auspices of the Department of Health and Human Services, which deals with public health concerns. The CDC’s primary agenda is more nationalistic in nature and focused on the prevention of disease and disability of United States citizens in areas of public health such as infectious disease, occupational safety issues, environmental health, and food borne pathogens and in chronic illnesses such as diabetes and hypertension [6]. The CDC wears multiple hats when dealing with an outbreak like Ebola which has primarily been affecting West Africa by advising healthcare workers who treat Ebola patients in these countries, by assisting hospital not only in the United States but also abroad including West Africa on standardized approaches to treat Ebola victims, on advising travelers and students who may travel to these countries for medical missions or tourism purposes, on assisting providers and lay folks on the signs and symptoms of Ebola, including time frames where these symptoms may occur, so that timely screening, diagnosing and treating can begin. In addition, the CDC has been in the forefront of helping US hospital in preparing for Ebola by having specialized units built in case of an outbreak and training clinicians on best practices to handle Ebola patients including the usage of personal protective gear. Furthermore, the CDC has been advising hospital on how to sterilize equipment and rooms formerly used for Ebola patients and advising foreign governments on ways the transmission of Ebola can be halted including basic things such as hand washing techniques and appropriate breast-feeding to prevent further dissemination to babies by infected mothers [7].

Governmental Response

The countries most affected by Ebola in West Africa, including Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, have with the assistance of WHO, CDC and non-governmental organizations, have focused on the social underpinnings in their lands which has led this virus to flourish including lack of a robust health system, poor governmental organization and oversight, poverty and political conflict [8]. There is increased emphasis on enhanced screening of this disease, allowing international medical experts and agencies to come into their countries and evaluate the healthcare realities on the ground, assist agencies by providing the minimal resources they do have to help combat this epidemic. Furthermore, there is increased emphasis that better health system with more diligent screening and elimination of social stigma could encourage folks to treat care and enhance recovery efforts when dealing with this virus. Education also is key, as these nations have all suffered with the portrayal of HIV/AIDS destroying the lives of their citizens and the negative affect this can have on trade and tourism. The United States, with the assistance of the United Nations and other developed countries, has spent resources both medical, financial and social to help alleviate some of the difficulties this part of the world is facing with varying success; an attempt worth doing to help lay the ground for a more resourceful healthcare model for the next potential epidemic.

Summary

The challenges in front of the CDC, WHO, governmental organizations can seem at times insurmountable but through vigilance and dealing in a timely manner with issues such as Ebola can help mitigate this situation in the long term. In a bid to prevent a pandemic from occurring, these organizations have taken upon themselves, with assistance from other non-governmental sources to tackle this problem in an effective manner. Although, thousands of lives were lost in this epidemic, timely intervention did prevent it from evolving into a worldwide pandemic. It is imperative that coordination, as seen in West Africa ravaged by Ebola, can play a crucial part in not only educating citizens to seek care if stricken by disease but also to encourage change on a fundamental level to the social structure of these countries to remove the stigma associated with disease.

Recommendations

It is my firm belief that as the world gets increasingly interconnected, there will be an enhanced likelihood that diseases will spread faster across the globe in not tackled at the onset. It might be prudent to develop a rapid response disease team which can go anywhere in the world in 48 hours to deal with any potential calamity. Yes, this will require substantial resources but our options remain limited in this endeavor. Another option could be having a team like this based on every continent so the response time can be quicker, however this might lead to developed countries having teams with more resources and could lead to health disparities. Overall, it is in the best interests of all to ensure that timely universal healthcare be available to all the citizens of this world lest we falter to a pandemic with no regard to social standing

To read more about this article: https://irispublishers.com/wjypr/fulltext/global-health-global-infectious-disease-control-systems.ID.000517.php

Indexing List of Iris Publishers: https://medium.com/@irispublishers/what-is-the-indexing-list-of-iris-publishers-4ace353e4eee

Iris publishers google scholar citations: https://scholar.google.co.in/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=irispublishers&btnG=

#journal of yoga#World Journal of Physical therapy and Rehabilitation#journal of physical therapy#Journal of Rehabilitation

1 note

·

View note

Text

The only reason the CDC and states went to the extreme with SARS-CoV 2 and not MERS/SARS, Ebola, or the Swine Flu is how Contagious they are.

SARS/MERS were confined to hospitals. SARS-CoV 2 started in the community.

Ebola virus disease is not transmitted through the air and does not spread through casual contact, such as being near an infected person. Test and Trace was able to isolate them before it could spread.

SARS and MERS: Deadly, but not easily spread

In late 2002, an emerging pathogen that likely spilled over from the animal world started to cause severe respiratory illness in China. Sound familiar? Through the first half of 2003, the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) spread through 26 countries, infecting at least 8,098 people and killing at least 774.

If the name didn’t give it away, SARS was caused by a virus similar to the one that causes COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, but it didn’t have nearly the same impact. This is in spite of having a relatively high case fatality rate of 9.6 percent, compared to the current estimate for COVID-19: 1.4 percent.

SARS and MERS didn’t cause the same level of devastation that COVID-19 has largely because they aren’t as easily transmitted. Rather than moving by casual, person-to-person transmission, SARS and MERS spread from much closer contact, between family members or health care workers and patients (or, in the case of MERS, from camels to people directly). These viruses also aren’t spread through presymptomatic transmission, meaning infected people don’t spread it before they have symptoms. Once people got sick, they typically stayed home or were hospitalized, making it harder for them to spread the virus around.

“By and large, except for a couple of mass transmission events, almost all of the transmission of SARS was within the health care setting, when you have an aerosol-generating event like intubating someone or dialysis,” said Stephen Morse, an infectious disease epidemiologist at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health. “So basically, you could control SARS by improving infection control and prevention in the hospitals.”

SWINE FLU was highly contagious BUT NOT AS DEADLY.

Swine flu: Easily spread, but not as deadly

In the spring of 2009, a new version of the H1N1 influenza virus — the virus that caused the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic — emerged and began to spread rapidly. The swine flu killed anywhere from 151,700 to 575,400 people worldwide in its first 12 months, through April 2010, according to estimates from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and may have infected over 1 billion by the end of 2010.

The swine flu spread easily person-to-person, just like COVID-19, and possibly even from people who were presymptomatic. Its R0, or R-naught, a measure of how many people an infectious person could infect, is between 1.4 and 1.6. This is a little lower than COVID-19, which experts estimate has a R-naught of between 1.5 and 3.5, but it still means H1N1 is a very infectious virus.

So why didn’t the swine flu overwhelm our health care systems and grind our economies to a halt? The main difference is that it ended up being a much milder and less deadly infection. There are a range of estimated case fatality rates for swine flu, but even the highest, less than 0.1 percent, are much lower than the current estimates for COVID-19.

“The 2009 pandemic, the H1N1 swine flu, that [disease] spread very, very well, but the fatality rate was quite low, and that’s the reason why it wasn’t dubbed as a particularly serious pandemic,” said Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and a member of the White House’s coronavirus task force, in a February livestream.

Even with such a low case fatality rate, the swine flu had a high overall death toll due in part to how easily it spread. With an even higher case fatality rate and perhaps even a higher rate of transmission, COVID-19 has required drastic measures to prevent its spread.

Ebola: Very severe, but hard to contract

Ebola first emerged in 1976, and the world has weathered outbreaks at various points since then, including one in West Africa from 2014 to 2016. It’s a severe disease that kills, on average, 50 percent of people who become infected, according to the World Health Organization. Yet just over 11,000 people died during the 2014-2016 outbreak, which was largely isolated to the region where it emerged.

Similar to MERS and SARS, Ebola is not easily transmittable. Infected people don’t spread the virus until they start showing symptoms, and even then the virus is hard to catch because it is spread through direct contact with the bodily fluid of an infected person, like blood, sweat, and urine, rather than through the kind of particles produced when someone sneezes or speaks. Unless you’re nursing patients (either at home or in a hospital setting) or tending to their body after they’ve died, it’s unlikely you’d acquire the infection.

Ebola also tends to cause pretty severe and identifiable symptoms, such as fever and fatigue followed by vomiting and diarrhea. Not only can infected people not spread the virus until they’re sick, but once they become sick, they’ll know it.

“If you want to see illnesses which are controllable, they all have transmission very much tied to symptoms, and this includes SARS and Ebola,” said William Hanage, an epidemiologist at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “If you’re in an Ebola zone, you can be pretty sure whether or not the person you’re talking to is a potentially risky contact.”

This makes it easier to isolate infected individuals and protect health care workers to limit the spread, which is what occurred in the 2014-2016 outbreak. It’s a striking difference from COVID-19, which we know can be spread without any symptoms at all, and even when people get sick, some people might have symptoms so mild that they’re not sure they have COVID-19 in the first place.

In each of these cases, the viral outbreak lacked one of the key components that COVID-19 has that allowed it to tip over into a global pandemic. “SARS-CoV-2 is kind of a perfect storm,” said Angela Rasmussen, a virologist at Columbia University who specializes in infectious diseases.

COVID-19 can be mild enough that some people who have it don’t know they have it. It’s also easily spread, can be transmitted by presymptomatic people and is severe enough to kill a significant share of those who have it. All combined, the novel coronavirus has led to an outbreak that is unusually difficult to track and control. The seismic shift in our everyday lives is happening for a reason.

CORRECTION (April 15, 9:40 a.m.): An earlier version of this article misstated the number of people who died from swine flu since 2009. Between 151,700 and 575,400 people died in the first 12 months after the virus emerged; that range does not include all deaths since 2009. The article has also been updated to make clear that the swine flu infected over 1 billion people by the end of 2010 — again, that does not include all infections since 2009.

https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/why-did-the-world-shut-down-for-covid-19-but-not-ebola-sars-or-swine-flu/

1 note

·

View note

Text

Pandemic and Pandemonium: Sickness in Horror

Well, it’s official: Novel Coronavirus, COVID-19, has been declared a pandemic -- ie, a new and widespread infectious disease actively infecting people throughout the world. For most of us currently alive, this is the first time we’ve seen a pandemic. It’s certainly the first time any of us have seen the kind of city-wide or country-wide quarantine measures currently being employed.

It’s an anxiety-inducing situation for sure. And people are dealing with that fear in different ways. Some folks are hoarding bottled water and toilet paper. Some folks are checking the news compulsively. Some folks are finding 20-second-long songs to sing while washing their hands.

And some of us are looking for horror fiction that might just mirror our anxieties and give a momentary but welcome catharsis.

Germs have existed since, well...the beginning of life as we know it. And for as long as humans have been alive, we’ve sometimes gotten sick from these microscopic invaders. It’s just a part of being alive. Everything gets sick sometimes, and humans -- who live in large complex groups and have a lot of casual contact day-by-day -- get sick a lot.

There’s a lot to fear from widespread illness:

Germs are invisible to the eye, so you can’t necessarily see the threat coming for you

Because infection is carried from person to person, mistrust and even hostility can grow toward people who appear ill (whether or not they really are sick)

Controlling the spread of disease often requires social isolation and can invite a loss of rights (ie, confinement)

The disease itself can have terrifying effects, from gross symptoms to death

If enough people get sick, it can disrupt the machinery of society, causing problems with food, electricity, healthcare, law enforcement, you name it.

Now, in real life, things don’t usually get that bad, especially in modern times when we have advanced healthcare and science and great communication. History’s greatest pandemics, from the Black Death (bubonic plague) of Europe in the 1300s to smallpox in the US in the 1700s to the worldwide Spanish Flu epidemic in the early 1900s, have been devastating -- but obviously, humanity has survived them all, and the numbers have been less terrible each time. With the power of antibiotics and vaccines and anti-virals and advanced medical interventions, we can save a lot of lives.

But we can’t save all of them -- which is why anxiety still lingers, and why stories about pestilence remain compelling.

The Magic of Fictional Viruses

When it comes to fictional illness, viruses usually end up in the spotlight. Some of the nastiest diseases in history have been bacterial infections -- Bubonic Plague, syphilis, typhoid, tuberculosis. Now that we have antibiotics, these once-deadly illnesses are essentially wiped from the modern consciousness.

But viruses are trickier. We have not yet developed a singular treatment as effective against all viruses as antibiotics are against bacteria. Instead, we rely on vaccines to immunize us against them. But vaccines are individualized, working only for the specific disease they’ve been developed to treat -- and if a new virus pops up, it takes time to craft the response against it.

Viruses also function in ways that make them especially attuned for horror:

They are smaller and less complex than other microorganisms, and it’s debatable if they are even, strictly speaking, alive.

Their only method of reproduction is by invading a cell and injecting it with its own genetic material; viruses cannot reproduce without a living host.

Because they reproduce quickly and rely on their host cells, viruses can swiftly mutate and change

Some people can be carriers, able to spread the virus without ever knowing that they’re sick or showing any symptoms

It’s little wonder then that viruses in fiction can cause all kinds of things -- zombies, werewolves, insanity, infertility, even turning your body to stone. In modern horror fiction, viruses often fulfill the role previously occupied by magical curses.

Horror Recommendations for Disease Fiction

With a global pandemic currently active, the CDC is recommending that people self-isolate whenever possible -- working from home, avoiding large crowds, and abstaining from touching people. So do your part to protect yourself and the vulnerable people around you by staying home and watching movies or reading a book instead. Here are some thematic lists.

“Realistic” Contagion Stories

If you’d like to watch a tense medical thriller rooted at least partly in realism, try one of these:

Outbreak - A california town is quarantined to stop the spread of an Ebola-like virus.

Contagion - A woman brings home a deadly virus that triggers a quarantine, complete with social upheaval and looting.

Pontypool - A radio disc jockey reports on a dire, apocalyptic pandemic while in isolation in Ontario

Containment - A TV series about a city that falls under a quarantine to prevent the spread of an Ebola-like disease; it's partly medical drama, partly commentary on social conflict

Apocalyptic Stories

Curious about what happens after the fall of mankind? So are a lot of authors and filmmakers.

The Last Man - Did you know Mary Shelley wrote an apocalypstic novel about a world-ending epidemic as a way to process grief about her husband's death?

The Stand - Perhaps Stephen King's greatest epic, the book details the fall of civilization as we know it and its brutal, power-struggle-fueled rebuilding in the wake of a devastating flu.

Oryx and Crake - Margaret Atwood conceived of a trilogy of near-future dystopia focused on genetic engineering, a plague, and the horrors of technology. Start with this one and read all three if it grips you.

I Am Legend - Richard Matheson's short novel is often adapted, but you can't beat the original. A plague novel, a zombie novel and a vampire novel all rolled into one.

It Comes At Night - A story of isolation following a deadly outbreak, and also a question of sanity and the choices people make in difficult positions. (full disclosure: I didn’t like this movie much, but it’s very well-reviewed so you might like it more)

Weird Chaos Viruses

I’ve talked about zombies before at great length, so I won’t recommend anymore traditional zombie tales -- just go read my other list for those recommendations! But sometimes apocalypses come by not-quite-zombies, so let’s talk about those:

Bird Box - The novel by Josh Malerman or the film starring Sandra Bullock, take your pick. Both are about a woman trying to survive in a world torn asunder by a an eldritch evil that drives you to madness if you see it.

The Happening - One of M. Night Shyamalan's more ridiculous films, but one I can't help but guiltily enjoy. An unexplained event drives people to commit suicide (in increasingly ridiculous ways), creating a world-threatening pandemic.

The Crazies - The original 1973 film and the 2010 remake both deal with an outbreak of a bizarre illness that causes people to go, uh, crazy. In a murder way.

Cabin Fever - Eli Roth’s directorial debut, this is a classic gross-out film franchise about a flesh-eating virus that chews its way through a bunch of young campers.

Dreamcatcher - Basically exactly the plot of Cabin Fever, except with aliens and some It cross-over cosmic horror. A decent Stephen King novel and a fun, if cringey, film, take your pick.

Mimic - A sci-fi approach involving cockroaches, genetic engineering, and bad ideas. Did you know this was co-written and directed by Guillermo del Toro and was the first Norman Reedus movie?

Cold Storage - A wonderfully gross debut novel by David Koepp featuring mind-controlling fungus.

The Troop - Nick Cutter’s gross-out novel is billed as “28 Days Later meets Lord of the Flies” which is basically everything you need to know. Monstrous tapeworms + boyscouts = bad times for all.

The Thing - A research team encounters a terrible alien parasite in an isolated frozen wasteland.

Historical Horror

The Black Death is one of the oldest, best-known, most-historically-significant illnesses in the Western world, so lots of people have told stories about it -- but it’s not the only epidemic in town. If you prefer your disease horror with a side of history, try one of these:

Black Death - Not a great movie, but it has Sean Bean and Eddie Redmayne and some exceptional gore, so it gets a vote just for that. It’s not about the plague so much as it’s about witchcraft, but it fits.

The Masque of the Red Death - One of Edgar Allan Poe’s finest stories, in my opinion. You can read this online in multiple places if you don’t have a Poe collection handy, and there’s a lot of audio and short films for it too so take your pick.

Love in the Time of Cholera - Like it says on the tin, this is a book about life and love and a cholera epidemic. Gabriel Garcia Marquez is a masterful writer, so this is well worth picking up for the quality of prose and storytelling alone.

The Plague - Part social commentary, part plague story, this Albert Camus novel is heavy on philosophy, if you’re into that sort of thing.

Cabin Fever and Isolation

A lot of the stories already mentioned touch on themes of isolation, quarantine, and cabin fever, but if you’re staring down the long barrel of social distancing and want more stories about going crazy in enclosed spaces, consider adding:

The Shining - The Stephen King novel and the Stanley Kubrick film are both excellent in their own ways, and I recommend both. A family makes the unwise decision to stay alone in a haunted hotel through a long snowed-in winter. It ends badly.

Devil - However bad your life is, it’s probably not as bad as being trapped in an elevator with the literal devil, which is the premise of this film.

The Cabin at the End of the World -- You didn’t think I’d write about apocalypse scenarios without finding a chance to plug my favorite Paul Tremblay novel, did you? Part home invasion, part psychological horror, part cosmic apocalypse, 100% terrifying.

Now, go forth and enjoy many a movie night, or curl up and treat yourself. Social distancing never felt so deliciously spooky ;)

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

« Democrats want to govern because they believe government has a chance to do good. This means even the party’s most left-wing members will compromise to take a step or two forward even when they want to take four.

Republicans, on the other hand, are riven between those willing to govern — even, occasionally, with Democrats — and those who will be satisfied only if Trump is president. They presume this would allow them to roll over the left, the liberals and the moderates alike. »

— Columnist E.J. Dionne at the Washington Post.

Most Republicans are not really that interested in governing – except for persecuting people different from them and giving big tax breaks to the filthy rich. The perpetual culture war is all that really matters to the GOP.

Remember the famed "Infrastructure Week" during the Trump administration? If not, that's because it never happened during the 208 weeks of Trump's term. He was probably too busy rage-tweeting from the bathroom to be involved in the actual work of governing.

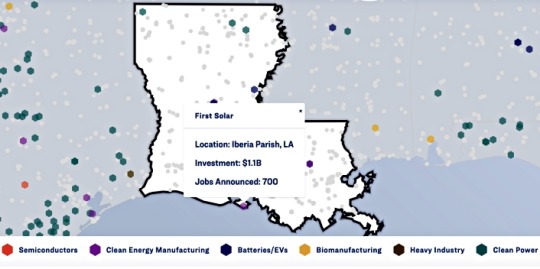

In contrast, infrastructure improvement was promised, passed, and is currently in the process of being delivered by Joe Biden. Check the map in the link below to see projects in your state.

Investing In America

Even in Speaker "MAGA Mike" Johnson's Louisiana there are many local people benefiting.

With Democrats you get job creation and investment. With Republicans you get vengeance and retribution with a heavy dose of incompetence.

Anybody who tells you that both parties are alike has the veracity of George Santos. Nobody talks about the Ebola outbreak of the early 2010s any more because the Obama administration handled it competently. The Trump administration completely botched the COVID-19 outbreak right from the start and America suffered much more because of his ineptitude and indolence.

#the two parties are not alike#governance#infrastructure#democracy#gop incompetence#“maga mike” johnson#louisiana#democratic job creation#joe biden#e.j. dionne#election 2024

6 notes

·

View notes

Link

Barack Obama’s efforts to replenish America’s stockpile of protective equipment for healthcare workers were repeatedly blocked by Republican lawmakers, an investigation has found.

The investigation by ProPublica found requests for funding to purchase protective equipment and train medical staff to prepare for future outbreaks were denied by a Republican-controlled House of Representatives that was filled with Tea Party-affiliated politicians.

Citing budget documents, as was as administration and congressional officials involved in negotiations, the report discovered that “had Congress kept funding at the 2010 level through the end of the Obama administration, the stockpile would have benefited from $321m (£259m) more than it ended up getting.”

Healthcare workers treating coronavirus patients across the country have complained about a lack of proper protective equipment. Many are having to reuse masks, which puts them at greater risk of contracting the virus.

As the coronavirus has continued to spread across the US in recent weeks, Donald Trump has repeatedly tried to shift blame for shortfalls in the government’s response to the outbreak onto his predecessor. Speaking last month, the US president said the Obama administration “made a decision on testing that turned out to be very detrimental to what we’re doing.” It was unclear exactly what decision the president was referring to.

Read more

Tracking the coronavirus outbreak around the world in maps and charts

When can we really expect coronavirus to end?

Everything you need to know on supermarket delivery slots

The dirty truth about washing your hands

Listen to the latest episode of The Independent Coronavirus Podcast

Mr Trump has also blamed the Obama administration and state governors for shortages of protective equipment for healthcare workers across the country.

Earlier this month he said he had “inherited a broken system.” He added: “They also gave us empty cupboards. The cupboard was bare … So we took over a stockpile with a cupboard that was bare.”

In fact, Mr Obama’s efforts to build up the stockpile and prepare for the next outbreak were stymied by a Republican-controlled House of Representatives that was heavily influenced by Tea Party-affiliated politicians elected on promises of cutting back government spending.

Speaking in 2014, Mr Obama argued it was necessary to set up a “public health infrastructure that we need to deal with potential outbreaks in the future.”

He said: “There may and likely will come a time in which we have both an airborne disease that is deadly, and in order for us to deal with that effectively we have to put in place an infrastructure, not just here at home but globally, that allows us to see it quickly, isolate it quickly, respond to it quickly, so that if and when a new strain of flu like the Spanish flu crops up five years from now or a decade from now, we’ve made the investment and we’re further along to be able to catch it.”

At the time, the former president was asking for hundreds of millions of dollars in funding to prepare the US for future pandemics, but the request was rejected by Republican politicians.

✕

The funding was a small part of an emergency request for $6.18bn (£3.98bn) to deal with the Ebola epidemic in 2014. As part of that package, hundreds of millions were to be set aside to help the country prepare for the next outbreak by procuring personal protective equipment for the country’s strategic national stockpile and training medical staff.

Most of that money was eventually secured, but funding for the future preparedness programmes was reduced. According to ProPublica, only $165m (£132m) went to the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention’s public health emergency preparedness programmes, which included the stockpile.

MORE ABOUT:

CORONAVIRUS |

BARACK OBAMA |

DONALD TRUMP

DAILY CORONAVIRUS BRIEFING

No hype, just the advice and analysis you need

Continue

Comments

Share your thoughts and debate the big issues

Learn more

Join the discussion

Loading comments...

24 notes

·

View notes

Link

Trump has learned well that, when the heat is on, he should just blame everything on that awful black guy and his supporters will eat it up. Thus, Trump has been loudly blaming President Obama for Trump’s own disastrous failure to handle the coronavirus pandemic.

Among other things, Trump has complained bitterly that the Obama administration didn’t leave behind a sufficient Strategic National Stockpile back in 2016. Trump, of course, had over three years under his own administration to remedy any supposed defects, and did nothing but demand more cuts. In reality, however, Obama did request more funding for the SNS, which the Republican-controlled Congress refused. If Congress had even just kept funding at the 2010 level through the end of the Obama administration, the stockpile would have had an additional $321 million.

“There had not been a big boost in stockpile funding since 2009, in response to the H1N1 pandemic, commonly called swine flu. After using up the swine flu emergency funds, the Obama administration tried to replenish the stockpile in 2011 by asking Congress to provide $655 million, up from the previous year’s budget of less than $600 million. ... Republicans took over the House of Representatives in the 2010 midterms on the Tea Party wave of opposition to the landmark 2010 health care reform law, the Affordable Care Act, also known as Obamacare. The new House majority was intent on curbing government spending, especially at HHS, which administered Obamacare. ... Congress allocated a compromise $534 million for the 2012 fiscal year, a 10% budget cut from the prior year and $121 million less than the Obama administration had requested. ...

“The next year, the ‘super committee’ failed to secure additional savings demanded by the Budget Control Act, triggering the automatic, across-the-board cuts. ... Under sequestration, the CDC, which managed the stockpile at the time, faced a 5% budget cut. In its 2013 budget submission, HHS decreased its stockpile funding request from the previous year, asking for $486 million, a cut of nearly $48 million. ‘The SNS is a key resource in maintaining public health preparedness and response,’ the administration said. ‘However, the current fiscal climate necessitates scaling back.’ ...

“In 2014, the Obama administration asked for and received billions of dollars to respond to the Ebola outbreak, but only $165 million went to the CDC’s public health emergency preparedness programs, including the stockpile. And in 2016, Congress granted emergency funding to respond to the Zika virus, but it gave the CDC less than half of what the Obama administration requested.

Congressional Republicans reversed their tactics as soon as the president was a fellow Republican: “During the Trump administration, Congress started giving the stockpile more than the White House requested.” No thanks to Trump, though, who has repeatedly demanded that Congress allocate less funding:

“During the Trump administration, the White House has consistently proposed cutting the CDC and the HHS Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response, which took over stockpile management from the CDC. Congress approved more stockpile funding than Trump’s budget requested in every year of his administration, for a combined $1.93 billion instead of $1.77 billion, according to budget documents.The White House budget request for 2021, delivered in February as officials were already warning about the dangerous new coronavirus, proposed holding the stockpile’s funding flat at $705 million and cutting resources for the office that oversees it.”

#coronavirus#Barack Obama#Donald Trump#novel coronavirus#COVID19#pandemic#Obama#President Obama#POTUS#Trump#President Trump#Trump lies#LiarInChief#lying liars who lie#scapegoating#blame#SNS#Strategic National Stockpile#Republicans#GOP#Congress#Tea Party#budget#federal budget#CDC#Centers for Disease Control#HHS#Health and Human Services#Department of Health and Human Services

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vaccine makers shielded from all liability as adverse reactions pile up

The potential health risks linked to fast-tracking vaccines loom large. On December 18, some 3 150 vaccine recipients had reported “Health Impact Events” according to the US CDC. This was from only 272 001 doses of the vaccine administered as of December 19.

Published: December 21, 2020, 8:52 am

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), a “Health Impact Event” means that someone is “unable to perform normal daily activities, unable to work, required care from doctor or health care professional”. The information was revealed by Dr. Thomas Clark, a CDC epidemiologist on the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, an independent panel that provides recommendations to the CDC.

Incidentally, the mRNA vaccines must be given twice, and the interval between the two doses is about three weeks. So one has a double risk of side effects.

At least five healthcare workers in Alaska experienced adverse reactions after getting the Pfizer vaccine, the Anchorage Daily News reported. One recipient, a nurse at the Bartlett Regional Hospital required emergency treatment for at least two nights.

An Illinois hospital halted vaccinations after four workers suffered adverse reactions.

The Washington Post quoted doctor and study participant David Yamane. He reported chills and headaches and having been so tired that he fell asleep on the couch in the afternoon and only woke up the next day bathed in sweat. “These symptoms are no joke,” the medical professional told the newspaper.

The reported allergic reactions that occurred in some are even more dangerous. They can show up in the form of rashes, but they can also cause shortness of breath and become life-threatening. It is believed that this reaction is caused by the nanoparticles in the lipid shell that surrounds the actual ingredient according to Dr. Peter Marks, the director of Food and Drug Administration’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research.

Four cases of facial paralysis also occurred when tested with the Biontech/Pfizer vaccine. The placebo group, i.e. those who received an ineffective injection instead of the vaccine, was not affected.

The most common short term – not long term – side effects that vaccine producer Moderna reported to the FDA were:

Injection site reaction in 91,6 percent of patients

Fatigue in 68,5 percent of patients

Headache in 63 percent of patients

Muscle pain in 59,6 percent of patients

Joint pain in 44,8 percent of patients

Chills in 43,4 percent of patients

Some have even argued that the Covid-19 vaccine could kill 8-16 times more senior Americans compared to no vaccine at all.

In October this year, US Secretary of Health and Human Services Alex Azar said a countermeasures fund should cover injuries from Covid-19 vaccines, giving drug companies complete immunity from potential liability lawsuits.

But as the Wall Street Journal reported, the fund is not remedy for the American public. According to lawyers and vaccine experts, since it began processing claims, the fund has paid out $6 million on 29 claims, averaging $207 000 per person, compared with $585 000 on average per person for an older vaccine injury fund.

The new fund has an almost impossible threshold for proving a relationship between an injury and the vaccine, experts say. The newer fund also has a shorter statute of limitations, no avenue for appeals and does not pay damages for pain or suffering. It was set up in 2010 to cover harm resulting from vaccines for a flu pandemic, or drugs to treat an anthrax or Ebola outbreak.

In November, India and South Africa approached the World Trade Organization (WTO) to waive patent protections for Big Pharma’s vaccine roll-out. Both countries said they wanted to ensure that poor countries had equal access.

“There are several reports about intellectual property rights hindering or potentially hindering timely provisioning of affordable medical products,” India and South Africa maintained. They were backed by Pakistan, Argentina and Venezuela and many US nonprofit activists.

The Trump Administration’s Operation Warp Speed has spent more than $10 billion to advance vaccine clinical trials, manufacturing and distribution, according to the WSJ.

All rights reserved. You have permission to quote freely from the articles provided that the source (www.freewestmedia.com)

1 note

·

View note

Link

0 notes

Text

Daniel Berehulak is an award-winning independent photojournalist based in Mexico City, Mexico.

A native of Sydney, Australia, Daniel has visited over 60 countries covering history-shaping events including the Iraq war, the trial of Saddam Hussein, child labour in India, Afghanistan elections and the return of Benazir Bhutto to Pakistan, and documented people coping with the aftermath of the Japan Tsunami and the Chernobyl disaster.

His work has been recognized with two Pulitzer prizes. In 2015, for Feature Photography for his coverage of the Ebola epidemic in West Africa and in 2017 for Breaking News Photography for his coverage of the so-called war on drugs in the Philippines, both for The New York Times. In 2011, he was also a Pulitzer finalist for his coverage of the 2010 floods in Pakistan. These are some of several honors his photography has earned including six World Press Photo awards, two Photographer Of The Year awards from Pictures of the Year International and the prestigious John Faber, Olivier Rebbot and Feature Photography awards from the Overseas Press Club amongst others.

Born to immigrant parents, Daniel grew up on a farm outside of Sydney, Australia. Their Ukrainian practicality did not consider photography to be a viable trade to pursue so at an early age Daniel worked on the farm and at his father's refrigeration company. After graduating from The University of NSW with a degree in History, his career as a photographer started humbly: shooting sports matches for a guy who ran his business from his garage. In 2002 he started freelancing with Getty Images in Sydney shooting mainly sport.

From 2005 Daniel was based in London and from 2009 in New Delhi, as a staff news photographer with Getty Images.

As of July 2013, Daniel embarked upon a freelance career to focus on a combination of long-term personal projects, breaking news and client assignments.

He is a regular contributor to The New York Times.

https://www.danielberehulak.com/about

Daniel Berehulak is an Australian Independent photojournalist and regular contributor to The New York Times, based in Mexico City. His work is a constant endeavor towards better understanding of concrete realities like the lives of those affected by war, natural disasters and social injustice. His work has been awarded two Pulitzer prizes, six World Press Photo awards, three Visa d'Or awards and has been a teacher at the Eddie Adams Workshop and has been a speaker at various Universities and also the American Museum of Natural History. Daniel has photographed history-shaping events including the Iraq and Afghan wars, the trial of Saddam Hussein, the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, the 2015 earthquake in Nepal, government impunity in Mexico, and most recently the so-called war on drugs in the Philippines.

https://www.panasonic.com/global/consumer/lumix/s/daniel_berehulak.html

A native of Sydney, Australia, and a regular contributor to The New York Times, he has visited more than 60 countries covering history-shaping events, including the Iraq and Afghan wars, the trial of Saddam Hussein, Ebola’s spread in West Africa and most recently the war on drugs in the Philippines. He focuses on news and social issues and on those affected.

In 2015 he was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for feature photography for his coverage of the Ebola outbreak in West Africa for The New York Times. In 2011 he was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for his coverage of the 2010 Pakistan floods.