Text

My Best Films of 2021

I’m not sure whether this year felt longer than the other ones – especially as last year sought to destroy all things. But then again, I cannot believe there was a Saw film released this year. I saw it in York. It had Chris Rock? No? Huh.

Anyway, cinema’s languid recovery from COVID looks to be jump-started in the form of Spider-Man: No Way Home. I could be pompous about how it had to be a Marvel film, but I’d be kidding myself if was going to be anything else. No Way Home might’ve secured record-breaking business which is sorely needed for cinemas, but I hope it won’t dampen any exposure to films outside of the Disney superhero machine. Fortunately, there isn’t any doubt that the quality of films haven’t fettered in the slightest during this test time.

1. Quo Vadis, Aida?

Nominated at this year’s Oscars for Best International Feature, writer-director Jasmila Žbanić has produced a film which builds enough foreboding dread, whilst not drifting away from the courageousness of the woman at the centre of conflict. Whilst there is an historical profoundness to Quo Vadis, Aida?, it is a tense film which deftly examines the nature of human fragility.

2. Drive My Car

The relationship between art and self is at the centre of this adaptation of one of Haruki Murakami’s short stories (Men Without Women). Drive My Car is almost three hours long, but there is a strange potent quality which has stayed with me longer. It might seem on-the-nose as a Chekov parallel, but I think the disquieting revelations makes Drive My Car hypnotic.

3. Summer of Soul (...or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised)

Questlove’s concert documentary goes beyond being a restoration project (although I certainly don’t deny how incredible it is to find and restore all that footage). Summer of Soul is a rich melting pot of audience appreciation, live wire performances from Stevie Wonder to Mahala Jackson, and historical significance. It’s unmissable.

4. The Green Knight

There hasn’t been a more luscious feast for the senses this year than David Lowery’s telling of the Sir Gawain and the Green Knight poem. Haunting and melancholic, The Green Knight is also about true heroism. The way that legends are not always filled with pomp and circumstance, but are about the courage to confront what has already been set by ones actions.

5. The Power of the Dog

Jane Campion’s best film since In The Cut, is an enrapturing Western full of psychodramatic observations about male idolisation and menace. At the centre is a slippery and sweaty performance from Benedict Cumberbatch (his best), and from there The Power of the Dog is a queasy and tense power-struggle for masculinity.

6. Petite Maman

Celine Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire was last year’s film of the year. This year is a shorter, if perhaps a comparatively slight, offering. Nonetheless, Petite Maman is just as affective and heartbreaking without bludgeoning the audience with over-sentimentality. It hits the right balance between glee and sadness. Hard to do with a film about a child and their loss.

7. Procession

A documentary about Catholic abuse victims trying to deal with their trauma through acting on film, could have been a mess. In other words, for a subject as harrowing as this, Procession does not look for an easy emotion-tug. Thankfully, it is tactful, powerful and sensitive to make sure the anger, heartbreak and humour of the main subjects is brought to life in their visions.

8. Titane

The winner of the Palme d’Or this year, Titane is first and foremost a film about acceptance. The much publicised body horror elements can come after. This is thanks to the committed performances of Agathe Rousselle as the shape-shifting woman on the run, and Vincent Lindon as a grief-stricken father convinced that she is his son. Like with the director’s previous film, Raw, it looks for humanity within the horror. It’s undeniably profound.

9. First Cow

Director Kelly Reichardt has a way of shooting the Pacific Northwest (look to the likes of Wendy & Lucy, Night Moves, Old Joy) which is so engrained that on a big screen you can feel the earth and smell the trees. Like her latest, First Cow, it doesn’t sound captivating, but it feels more authentic than most things committed to screen.

10. West Side Story

Spielberg doing West Side Story, in a year of a number of big budget musicals, didn’t exactly excite me. However, I’ll be damned if I don’t want to see it again and again. The heartfelt ecstasy of the stage musical is something which is fully embraced in his version and, dare I say, made better. The gangs actually feel dangerous, most of the dated features from the original are worked around, and Spielberg shows that he still knows a thing or two about thrills. Of course he did!

#best films#titane#west side story#petite maman#drive my car#first cow#procession#power of the dog#summer of soul#quo vadis aida#green knight#2021#film#movies

1 note

·

View note

Text

Top Five Favourite Films of 2020

All the covers will proclaim 2020 to be “The Lost Year”. I’m almost taking bets on it. Pixar’s stodgily lukewarm Onward has had more staying power in the box office - by default - than any other Pixar film. But then again, what does that even mean anymore? Onward feels like five years ago. As 9/11 was the solid ink-border from the one era to the next, undoubtedly so is COVID-19. I hope there is still room for cinema, but it will never be the same. It might be the last end-of-year list I make which has theatrical releases. If movie theatres are to survive, the model will need to be substantially re-evaluated to make it more accessible. They cannot be considered as just treats for the penny-pinching masses.

Luckily, the amount of great films released this year does not suggest any sort of slowdown. Not in terms of quality anyway. The Assistant was a soul-crushing depiction of inescapable abuse, and the stifling judgement of the everyday was effectively carried in Lynn and Lucy. In terms of animation, Wolfwalkers is absorbing (even outside the big screen), and Pixar produced some of its most sweeping work with Soul.

Works which just missed out on the Top Five include: Sarah Gavron authentic coming-of-age London tale Rocks; Saint Maud, the shuddering debut by Rose Glass; Adam Sandler dragging us through the Diamond District in Uncut Gems; the wicked Brazilian horror-western that is Bacarau; and finally, Possessor, Brandon Cronenberg’s menacing and glorious sci-fi horror.

1. Collective

In a year of societal anger and institutional abuses, a documentary like Collective leaves you in an exhaustive slump. It opens with horrific footage of the Collectiv Nightclub fire and from there you think it is a straight aim: a group of journalists calling to attention the corruption and ineptitude of the government. What I think is extraordinary about Collective is that it does not impasse judgement on the political system directly. In the end, there are no triumphs or victories and yet it is a tactful insight into a few key figures looking to do right amongst the hopeless backdrop.

2. Portrait of a Lady on Fire

A year ago after I saw Portrait of a Lady on Fire (released in the UK this year). Since then there are breathtaking images which are still imprinted into my mind since the first viewing. What director Celine Sciamma manages to do is thrillingly exploit ‘the gaze’, and capture it in all its striking beauty. If that sounds pompous, it’s because I’m making it sound more over-sentimental than it actually is. If last year was a long time ago, I will keep Portrait of a Lady on Fire.

3. Lovers Rock

Steve McQueen’s Small Axe anthology is quite an achievement that to gripe at some the televisual lapses is fairly irrelevant. However, the standout is Lovers Rock; the second film out of five. If one were to see it in a movie theatre, it would be near-impossible to not be enraptured by the energy of the midnight, and not be intoxicated towards the end. Lovers Rock is about the harmony of a house lit up in celebration. One of the best party films of all time.

4. Dick Johnson is Dead

Let’s start on a passive note: with a concept that could have been so maudlin and icky in execution, it is such a relief that Dick Johnson Is Dead is successful. For a therapeutic project about their father succumbing to dementia, Kristen Johnson makes celebration the focus of love and death. It’s a warm, touching and, most of all, playful love letter to their father. There is more happiness than sadness to come of it.

5. Never Rarely Sometimes Always

The last four years have given some urgency for filmmakers to make polemical statements (and why shouldn’t they?). Never Rarely Sometimes Always is a sober film about abortion, but a fleeting film about a teenage friendship. The performances of the two women at the centre lift a film that could have been, understandably, distressingly bleak. Director Eliza Hittman is ingenious to capture the whole foggy emotional and logistical journey.

#best films#2020#film 2020#favourite#movies#lovers rock#portrait of a lady on fire#collective#dick johnson is dead#never rarely sometimes always

0 notes

Text

The Best Picture 2020 Round-Up

It has been a short awards season. The Golden Globes were closer to Christmas than the Super Bowl, and the BAFTAs fell on the latter. In a way, this has made this year more exciting than most. The quick succession of award ceremonies has made predictions more manic. Today I’m flipping between whether this year’s Best Picture and Director combination is going to be AB or AA, Parasite or 1917, Klaus or Toy Story 4, For Sama or American Factory? The Academy logic sometimes catches me out.

The list of nine films up for Best Picture (why not ten?) are made up of seven satisfying films, and two I would’ve been happy to lose. In its place? What about the panic-inducing rush of Uncut Gems? Heck, how about another potent foreign-language entry in the form of Celine Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady On Fire? Dolemite Is My Name was one of the most funny feel-good films of last year. Let us not mention how Hustlers was shunned in by the stuffed shirts at the Academy. Jennifer Lopez have you met Adam Sandler? Congrats, you both got unfairly stiffed in the acting categories.

So, in dealing with what we have, here are the Best Picture nominees ranked:

1. Parasite

The crowning achievement in this year’s Best Picture line-up; an genre-twisting social commentary with thrills to satisfy a universal audience. There’s not much use blowing into the flames when the bonfire is already alight, but Parasite is brilliant. In craft and in tone, it is a multi-layered Swiss Watch of a film and, like the house, reveals hidden areas you don’t expect. So I will stop blowing my own horn and making this sound like hyperbole. Parasite needs to be seen.

2. Little Women

Greta Gerwig’s version of Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women is amazingly fresh. I say amazingly because it could’ve been a handsome adaptation with the Gerwig stamp, and a fresh-faced stellar cast. Fortunately, Little Women packs all the emotional intelligence and understanding beyond my expectations. There is nothing that feels sloppy about the back-and-forth timeline; it serves to highlight the kindship through ambitions, disappointments, and decisions. Nevertheless, the lack of nominations seems to draw a baffling consensus this is somehow easy to do.

3. Marriage Story

As adult divorce dramas go, Marriage Story is the most readily accessible in a while. The film is a relief in that it doesn’t dwell on the devastation, nor is it a cold and stiff depiction - which I have to admit, didn’t warm me to Noah Baumbach’s previous work The Squid and the Whale. No doubt, a good heft of Marriage Story’s comic-tragic achievements are through the performances. Plus, there is deft calculation to the film’s emotional heights. Be it through scenes that you wouldn’t imagine would turn into a fierce battle, or two contrasting sequences involving Sondheim.

4. The Irishman

The Martin Scorsese stamp is apparent throughout most of The Irishman. The moments which ring the loudest are sometimes too on the nose and, arguably, could be dispensed. Nevertheless, the film is a masterful self-reflection of the fading glamour of the criminal underworld. What I about The Irishman is how it captures the natural final destination any human being; simply becoming old. The last third of the film makes up for any slouches in the narrative.

5. Once Upon A Time In Hollywood

Quentin Tarantino plows on as the filmmaker who just can’t help himself. That is the downfall of most his films post-Jackie Brown. The good news is that Once Upon A Time In Hollywood is Tarantino’s best film in this aforementioned era. It is a riot most of the time, and infuriatingly ill-disciplined the some of the time (the Bruce Lee section feels like a self-inflicted intermission). Tarantino is a master of set-pieces and Once Upon A Time In Hollywood thrillingly reminds us there is still no one quite like him.

6. 1917

At the time of writing, the annual backlash of the over-achiever has already begun. This year, it is 1917. I think it is already burdened with an archetypal get from A-to-B wartime narrative. No question that’s what it mostly is, but the flourishes are remarkable none-the-less. The camerawork is undeniably gripping and impressive, and it contributes to the inescapable task the two soldiers face (I also extend my plaudits to George McKay). If 1917 looses out on Best Picture, we might raise our estimations again.

7. Ford Vs. Ferrari

Like Rush, I remember watching Ford Vs. Ferrari like a race car speeding by: you get a gust of wind which captures your breath, then it disappears into distance. My point is that James Mangold has made a dependable, Saturday afternoon blast of a film. With an ideal sound system, it is gloriously deafening to hear ever gear-change and engine rev. However, judging it as an awards contender, Ford Vs. Ferrari seems like a curious choice. That’s no con really. The film’s lack of pretension makes it stand alone in the Best Picture pack.

8. Joker

As divisive as Joker has become, it think it sits more uncomfortably in thematic areas. It is a comic book film with the coveted “Winner of the Golden Lion 2019” stamp on it. So with that in mind, it’s no biggie to say Joker is dunderheaded. Mental health, societal inequality, poverty – it has all the tact of an annoying toddler bashing you around the head with an inflatable hammer. Yet I don’t hate Joker. It’s a clumsy imitation of Seventies revenge flicks (and yes, The King of Comedy), and I guess you can’t fault the film’s commitment to that grimy tone.

9. Jojo Rabbit

Speaking of imitations, JoJo Rabbit desperately wants to chum up with Mel Brooks and Wes Anderson. It seems to be working with popular audiences, and not working with critics. I have to admit, I fall into the latter. Why? It’s not a bad film, but it’s a safe film. Most of the jokes are too broad and Taika Waititi as Hitler comes across as self-satisfying. Apart from one or two moments of effectual moments, the drama feels shop-bought. Jojo’s message is right, but it lacks the transgressive heights for which I wish it attained.

0 notes

Text

Best Films of 2019

As we stumble into the award season, there is a stick in my craw. Well, not just my craw: 2019 should be the year for truly exceptional works by female directors to be acknowledged. But still no. Nada. Even the usually reputable BAFTAs were in on it. Seriously, what makes Todd Philips the director of the year over Lulu Wang, Olivia Wilde, Marielle Heller, Lorene Scafaria, Claire Denis? Those list of directors alone made films which almost made my list. Out of all the years, I truly thought 2019 would be the turnaround year for female representation. The wait, infuriatingly, continues.

In the meantime, here are the honourable mentions of films which just missed the cut:

In Fabric

The Farewell

Ash Is The Purest White

Hustlers

Pain and Glory

Booksmart

High Life

Us

Capernaum

Atlantique

1. Parasite

Boon Joon-Ho’s Parasite already has a line-up of awards in its pocket and I’m sure more will follow, but it is typically sly and unpredictable in ways Korean blockbuster psychological thrillers tend to be. For instance, I was reminded of Burning last year; a love story twisting into a quasi-murder mystery. Parasite is an upstairs/downstairs tale about the infiltration of the upper class. The first half is like a societal heist movie, but what lurks underneath the house brings a tinge of horror and unexpected pathos. It is the most deserving winner of the Palme d’Or for a while, and a proven crowd-pleasing thrill.

2. Bait

Bait goes beyond a stylistic experiment. It is an intoxicating Cornish film shot on black-and-white 16mm film with an asynchronous, post-production dialogue track which smacks of a Pathe newsreels. Indeed Bait is about the past being frayed away and it is ingrained within the very fabric of the film, just like the crab traps which are rotting away and the gloom that lingers forebodingly over the Cornish seaside town. It’s hard not to feel swept in by the melancholia of local tradition fading away. Director Mark Jenkin is deft to not condemn the outside folk moving in. Bait is breathtakingly compassionate, weirdly funny and heartfelt.

3. If Beale Street Could Talk

There is a beautiful and potent harmony in Barry Jenkins’ adaptation of James Baldwin’s If Beale Street Could Talk. The opening crane shot is of two blossoming lovers walking in the park; the camera lolling above their heads as the Nicholas Britell score floats through the air with the leaves. Jenkins’ has already proven himself with Moonlight in terms of matchmaking mood with environment. This is prevalent in the pivotal lovemaking scene, which is hypnotic and monumental. In the face of racial persecution and justice which will never be found, If Beale Street Could Talk is about the hoariest of all life-affirming lessons: love conquering all.

4. For Sama

The Syrian horror story is an ever-present subject in documentary; from the hard-hitting intimacy of The Last Men in Aleppo to the Oscar winning short The White Helmets. The images of rubble and bodies does not get any easier to watch, and For Sama is as relentlessly heart-breaking as they come. Sama is a child born in the midst of the Syrian Civil War, and it doesn’t take long for her to adapt to the startling noise of explosions going off next door. Yet, miracles do happen in the film: one particular scene involving a stillborn child left me rocked in my seat and breathless with emotion. Through the never-ending trauma is a sense of resilience and a drive for life.

5. The Souvenir

In 2020, I eagerly await Joanna Hogg’s part two to The Souvenir. The romance at the centre is beguiling; it feels raw without resorting to outright hysterics. Both Honor Swinton Byrne and Tom Burke are fascinating, and the framing of their fractured communication is exhaustively captured; the audience prays for one half to bridge to the other. It is perhaps appropriate that Swinton Byrne plays a film school student: compromises are made, money is thrown, and how long can one afford to meet halfway before cutting the heavy losses? Love and making art, in The Souvenir it is a doomed romance.

6. Monos

Monos is one of the more sensual experiences this year. It is the marriage between the uncompromising environment of the Columbian wilderness and the savage breakdown of the human function, which makes Monos encapsulating (especially in a cinematic setting). Another thick layer is Mica Levi’s spectacularly reverberating score; combining primitive whistles and otherworldly electronic synths. How unfortunate it will not get a look in at this year’s award season. Monos is as close as you’ll get to the edge of the world.

7. Happy As Lazzaro

In a not-too-dissimilar camp to Monos is Happy As Lazzaro. Here, the titular character is a victim of a strange misfortune: a figure whose existence is a mystery. Lazzero’s compliance isn’t necessarily his own undoing, but the people see him as a tool and his family doesn’t value him any more than the world does. Nature is at the centre of Lazzaro’s fate and is the closest to being his true guardian. Writer-director Alice Rohrwacher tells a rich parable full of absurdist cues, imagery and compassion for the doe-eyed boy.

8. Marriage Story

If there is any true toxicity to the divorce in Marriage Story, it is prodded out by the systematic and legal process. With deservedly well-received performances by Adam Driver and Scarlett Johansson, the film portrays the kind of couple who would go out of their way to avoid battle. Compared to Noah Baumbach’s The Squid and the Whale, Marriage Story is more accessible. As marital dramas go, it does not conventionally dwell on the cold-heartedness. The film allows for a bit of rope to grip onto, in the form of humour and the odd Sondheim number.

9. Dolemite Is My Name

Dolemite Is My Name feels like the ideal Eddie Murphy project for this day and age; a wonderful balance between the crude humour that flew for him in the 80s, and a surprisingly insightful retrospective of the gap left in black mainstream cinema. Like Ed Wood and The Disaster Artist, it is a comedy with affection for the characters’ eccentricities. Whether the material is tasteful or not is beside the point, Dolemite Is My Name goes along with the rhythm and dress-up of Rudy Ray Moore’s act.

10. Little Women

Unfortunately, it looks like we are going to live in a year where Todd Philips is seen as a more deserving Best Director nominee over Greta Gerwig. Little Women is a crisp adaptation with the confidence to find something fresh with Alcott’s timeless novel. The time-hops is a device which pays off emotionally, and another ace-up-its-sleeve is a cast to die for (if one had to pick, Florence Pugh’s Amy is perfect). Little Women is a gem through and through. Like A Star Is Born last year, I never thought I needed another one.

#best films#2019#parasite#little women#dolemite is my name#for sama#if beale street could talk#the souvenir#movies#film#happy as lazzaro#bait#monos

0 notes

Text

Films of the Decade (1 - 10)

10. Bait

Bait slips onto the list in the nick of time It is a 90 minute, black-and-white film, shot on 16mm with a fully post-dubbed soundtrack, set in a Cornish fishing village. As a technical exercise, Bait is enrapturing. The village is trapped in a filmic past, with a Pathé-like atmosphere tied with a bygone era of thick fog and a thriving industrial landscape. This stylistic choice pares back the clutter of modern soundtracks and brings to the fore an elegiac and foreboding mood. Bait is a wonderfully strange film, and let’s hope the enthusiastic reception in Britain spreads internationally.

9. Mad Max: Fury Road

Mad Max: Fury Road has become the model/rebuttal for how high octane action should work. I don’t think it’s an original model. I still think a lot of the giddy nut-and-bolts foundations of Ozysploitation is carried on into Fury Road. Of course, this time the budget is larger and the audience is wider. Fury Road will be on many people’s list due to many technical elements coming together - believe or not - carefully and with precision. No big wonder that it was the most awarded film of the 2015. George Miller brings out the eccentricity of the characters and the cars with the same glory as we’d expect from a Tex Avery cartoon. So often we are used to action fatigue that when something like Mad Max: Fury Road crashes in, it’s like fresh oxygen. Too right, good action is the hardest feat to pull off.

8. Araby

Araby is a 2017 Brazilian film I just saw this year. A few critics have mused whether what they saw is the Film of the Decade (this claim was initiated by The Hollywood Reporter’s Neil Young, and followed up by Guy Lodge of The Guardian). It would probably be a stretch for me to include it as one of my Films of 2019, but no matter how many cinemas it missed, I still think Araby is indicative of the one-man’s odyssey through worn-down labour. What astounded me is how the film itself stumbles into a story: the first twenty minutes is a kitchen sink drama until a young boy finds a journal of a recently deceased factory worker. From there, it is a film about somebody else; the factory with a more lyrical story than expected. It’s a simple turn which makes sense. Araby is that journal; a precious story stumbled upon.

7. The Master

There Will Be Blood was the film of the Noughties. Over this decade, there were two end-of-year lists which had a Paul Thomas Anderson film at the top. Last year it was Phantom Thread, and back in 2012 it was The Master. The coolness of The Master is that most of the cinematic elements displayed have a drift to them - the hypnotic Jonny Greenwood score, the near-floating camera movements, and the frames which show Joaquin Phoenix as a character who could fly into an explosive rage or lie aimlessly hanging off a ship. It is, indeed, a demonstration of a filmatic masterclass. Phoenix and Philip Seymour Hoffman are the compelling acting duo ever put to film this decade.

6. Burning

South Korea has built a reputation of making some of the most warped psychological thrillers of the 21st Century. This year, Bong Joon-Ho’s simmering social treatise Parasite became the first Korean film to win the Palme d’Or at Cannes. The year before, Burning was touted as the being the frontrunner at the same festival. It is a film which is beautifully mysterious and an outstanding example of side-swiping the audience. What starts off as a love story turns into social critique, but then becomes a film about a possible murder mystery. It might be asking more questions than answering them, but all the questions are tactfully scintillating. Burning is two-and-a-half hours long, I was gripped enough to yearn for an extra hour.

5. The Act of Killing / The Look of SIlence

Joshua Oppenheimer’s double bill The Act of Killing and The Look of Silence make up for the most revealing documentaries of the decade. Both are gut-wrenching, devastating, and mentally exhausting. Especially in The Act of Killing. In what could’ve been a chargeless stunt, the participants of the Indeonesian Communist Massacre are given the resources to produce a film depicting their crimes. The end result is something disorientating, gleeful, and utterly grotesque. Something that lets us, the audience, into their callous ego. By the end, something manages to penetrate. One of the massacre orchestrators find introspection. It is an extraordinary moment. Unforgettable.

4. La Quattro Volte

La Quattro Volte is a made up of four segments, each encompassing the Pythagorean “Four Turns” of life: the human realm, the animal realm, the plant realm, and finally the mineral. As the synopsis indicates, it is a film with a lot to project. Deep thought, awe, and contemplation; the wonderful thing about La Quattro Volte is that it is dialogue free, only an hour-and-a-half long, and spatially aware without coming across as sparse. It’s a methodical film with room for humour. In fact, one long static shot of an uphill street gave one of the biggest laughs of 2010. It will be known as That Goat Film, but La Quattro Volte has more to say than most films twice its length.

3. The Social Network

For half the decade it seemed that The Social Network was set to be the defining film of the decade on the basis of social relevance and evocation. Yet Facebook grew exponentially and so are its issues and, arguably, its dangers in modern society, to the point that the Facebook of 2019 is not the Facebook of 2004. Yet David Fincher has a grapple on the foreboding; of what is lingering in the air. With Aaron Sorkin’s script, the characters are intimidating in their quick-fire smartassery. In the end, there is an inclination that they are stepping down into a rabbit hole. The Social Network is expertly crafted and understands that it need not be a film about Facebook. It’s a film about reputation, legacy and control.

2. Boyhood

For the last three years of the decade, I knew that the toss-up for the top spot was between Moonlight and Boyhood. It was pretty close to being a tie, and part of me wishes it would be. However, Richard Linklater’s Boyhood is an epic which lives up to its broad title. Better yet, it doesn’t follow through just one person’s navigation through life and phases: it follows the mother, the father and the sister. Linklater does it on a level which is without any hint of labour. Even with music and technological cues, it is still hard to pinpoint any jarring moments where the boy has gotten a year or two older. So take this as being indicative to Boyhood’s effortless brilliance: only now am I mentioning how the director filmed it over the span of twelve years.

1. Moonlight

Frustratingly, the envelope mix-up at the ceremony overshadowed any right Moonlight had to bask in prestige. It should’ve been a moment of pure celebration, because Barry Jenkins’ film is tremendous: a semi-tragic parable of a boy in three stages of inner turmoil. It is about sexual awakening, parental guidance and, yes, racial preconceptions of manlihood. On a stylistic level, Moonlight has a wealth of cinematic hues; Nicholas Britell’s poignant score feels like a boy trying to float on the surface of the ocean, the lighting is beautiful and it heightens those interludes in between the fights and shouting. Far from me to fawn over what has already been trumpeted, but Moonlight is extraordinary. The Academy may never be this right again.

Top 20 Films of the Decade

1. Moonlight

2. Boyhood

3. The Social Network

4. La Quattro Volte

5. The Act of Killing/The Look of Silence

6. Burning

7. The Master

8. Araby

9. Mad Max: Fury Road

10. Bait

11. O.J. Made In America

12. A Separation

13. You Were Never Really Here

14. Force Majeure

15. Paddington 2

16. Girlhood

17. Under The Skin

18. Dreams Of A Life

19. Song Of The Sea

20. Locke

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Films of the Decade (20 - 11)

What can be said with the utmost confidence is that the quality of film has not slackened. Every now and again, some curmudgeon will grumble that film “is not the same”, “not what it used to be”, “not like the classics”. Oh puff, it will continue to sustain and challenge. Always has, always will. The one ultimate takeaway from this decade is that of how film is seen. By the end of this year, Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman will be released on Netflix, thus proving financial carte-blanche for already established filmmakers is now available outside of the giant studios. Streaming is happening and next year the Disney juggernaut will follow suit with their own service - truly a new, somewhat unnerving era.

So in revealing my favourite films of the past decade, let’s celebrate the glut of amazing work these last ten years have produced. The list honorable mentions would stretch the circumference of the Earth, but I was close to including: Kathryn Bigelow’s nail-biting Zero Dark Thirty, Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s slow-burn procedural drama Once Upon A Time in Anatolia, the colonial fever dream that is Zama, Todd Haynes’ lush Carol, Leviathan and its biblical injustices, Gianfranco Rosi’s quasi-documentary Fire at Sea, the lip-smacking Raw, and Debra Granik’s outstanding Leave No Trace. Not to mention the countless animated features and documentaries which show no signs of letting up. Here’s to the bar being raised forever more as we sit in the dark.

20. Locke

If there is one film this decade for which the weight was placed entirely on the shoulders of one actor to make it work, it is Tom Hardy in Locke. Essentially, it’s about a man trying to “fix” things over the phone while driving at night. Ultimately, his professional and personal life is obliterating around him, all due to a silly one-night stand. What we hear are voices bombarding the tiny space of a car. What we register as an audience is down to the brilliance of Tom Hardy. It is a role many actors would relish and go to town, but Hardy’s performance is introspective, collected, yet far from calm. Locke would work brilliantly as a radio play, but what is also impressive is how it genuine it feels someone driving through the night; from the smooth humming of the company car to the amber lights overhead. It lends a crushing air of solitude.

19. Song of the Sea

Animation has been the most consistently reliable form of media over many decades. The bar is so high, that I honestly struggled to pick one for this list. I floundered between the ingenius of Pixar’s Inside Out, Isao Takahata’s beautiful swansong The Tale of Princess Kaguya, the jaw-dropping sweep of The Red Turtle, the laugh-riot of The Lego Movie, the list truly goes on. One film left me inconsolable with floods of tears, and that was Tom Moore’s Song of the Sea. It is a film soaked in folklore, but it doesn’t fall into the trap of being twee. There is wave upon wave of gorgeous animation being reinforced by themes of family grief, brotherly responsibility and heartbroken spite. Song of the Sea defines a terrific balance many animated films achieved this decade: sublime artwork matching exceptional storytelling.

18. Dreams of a Life

British documentaries continued the up-and-up throughout the 2010s. It was tough to decide between Clio Bernard’s innovative The Arbor, Asif Kapadia’s poignant Amy, the lovingly delicate Notes on Blindness and the compelling A Syrian Love Story. What Carol Morley manages to do with Dreams of a Life is bring poetic legitimacy to a heartbreakingly lonesome death: Joyce Carol Vincent wrapping presents in front of the TV, she dies suddenly, and is not found for another three years. The interviews with various friends and distant family confirms Joyce’s presence in the world, but the recreations provide her a body and soul so sorely deserved.

17. Under The Skin

There is a tragic forgone conclusion with Under The Skin. The interpretations are plentiful: is it a feminist discourse on male attraction? Alien alienation? Or the destructive nature of human beauty? Director Jonathan Glazer uses the recognisable star power of Scarlett Johansson to plunge her in the grit. She is an alien entity who scouts her prey on the Glaswegian streets. At first she obliterates the characteristic lustful male, then the lines shudder and blur. Her objective becomes lost and she wanders into the Highlands. Even if you don’t buy the meanings behind Under The Skin, it is a striking audiovisual exercise. Not least of all, Mica Levi’s haunting and quivering score.

16. Girlhood

Is it asking for trouble to include two ‘Hoods’ in amongst the pack (spoiler) ? Cèline Sciamma is one of the best female directors to come out of this decade (look out for the sublime Portrait of a Lady on Fire this year). Her ebullient compassion for her teenage subjects against the Banlieue is why Girlhood is a powerful entry in the already-reputable French social-realism subgenre. Where there is roughness there are some thrilling interludes of joy. In particular, one scene with the gang of friends dancing in a hotel room with stolen goods, all set to the affirming “Diamonds” by Rhianna. Sciamma knows how to capture the vibe of a moment of happiness and let it flower. It makes social realism less a one-note descent into collapse. It takes a knowing and deft hand to pull that off.

15. Paddington 2

Paddington has all the charm and playfulness of a well-crafted pantomime. Paddington 2 visually represents that perfectly through flip-book canvases, which pull back like a colourful and jaunty set change. What is lovely is how first film was a sigh of relief. In other words, Paddington as a beloved literary character has not only been untainted, but it has been brought so cleverly up-to-scratch. The warmth of its message about inclusiveness and family is nothing terribly new, but Paddington has so much heart to back it up. Comedically, the films pack just the right amount of innuendo and silent cinema show pieces, to make this sort of humour seem so fresh. Paddington 2 refines the winning formula.

14. Force Majeure

Force Majeure is about a family going on a skiing trip. The family are initially mundane in how well-maintained they are. They are financially stable, brush their teeth in a squeaky clean bathroom with their electric toothbrushes, and the children are all kitted up. However in one riveting long still shot, the solid family unit is doomed. It is the fallout of that one event and the marital crumbling which makes Ruben Östlund’s Force Majeure deliciously tense. Better yet, it makes one want to watch that one event again. Is the father’s one instinctive act a true reveal of his selfish character, or is it something worth forgiving in the heat of the moment? There are no sturdy answers and that is the consequence of a fleeting act.

13. You Were Never Really Here

Lynne Ramsay’s You Were Never Really Here is a psychological revenge drama in which the revenge is achingly taken away from Joaquin Phoenix’s contract killer and us as an audience. It is a film about trauma. The scenes of violence are either jolting or they are exhaustively unsatisfactory; that is how realistically it is portrayed. One scene in particular robs us of a clear picture of how violence plays out. Like Phoneix’s Joe, we are left with a cold sweat. Revenge is an unhealthy picture through and through. Ramsay makes us feel the discomfort and the lack of glory, at odds with what we are so used to seeing these days.

12. A Separation

A Separation is a constant roll-out of trail and consequence. The ‘separation’ has formally commenced in the opening scene. The couple addresses the camera with pleas and arguments. The judge they’re speaking to has a line waiting outside with couples in a similar predicament, but we’re dealing with one. The film presents the separation like a case study, and it continues to be gripping and emotionally charged throughout. Director Ashgar Farhadi scrutinises our judgement of these characters, for there is always one morsel of information that leaves us second guessing. In the end, the film is tragic because there is no right and wrong. What is clever about A Separation is that, whilst there is a steady underlying context which points towards Iranian society, it is a borderless film.

11. O.J. Made In America

“There’s no more powerful a narrative in American society than race”. O.J.: Made in America charts a monumental rise-and-fall narrative like no other. For the good part of 467 minutes, there is a wicked absurdity in how the American Dream is favoured and unstable. Ezra Edelman’s charting of O.J. Simpsons’ career, lifestyle and persona is set very knowingly against the relentless chronicle of racial injustice and poverty. It makes re-living the already well-documented murder trial gut-wrenching and compelling all over again. O.J.: Made in America is already touted as one of the best sports documentaries since Hoop Dreams. Like Hoop Dreams, it is little to do with sports, it is about everything around it.

0 notes

Text

Favourite Films of 2018

In lieu of a drastic shift in my personal development, going to the cinema has been getting harder. In July, I made the move to Vancouver and I confess that, even though I’m in closer proximity to a cinema in a big city, my schedule has been over-stuffed with growing up a bit more. Going to the cinema in Vancouver is a guilt-ridden treat now. Look at Vancouver in most photos or postcards, and you realise not many cities boast mountains lurking so close to the skyline. Assimilating to the culture means getting out. Being in a new environment pressures you more; like an obligation.

So this has been a year of two clean-cut halves: pre-move and post-move. In compiling a list of my favourite films, I realised there would be a territorial inconsistency. There is no conservative way of solving it, so this list is a hybrid of UK and Canadian releases. One or two of the films are not due for release in the UK until next year.

1. Phantom Thread

As much as I kept tossing between my top three films of the year for the top spot, Phantom Thread still stuck with me as being the most potent and exquisitely crafted. The film is presented like a piece of fabric; every bicker and interaction between three characters is compelling, the score is sublime, the acting is flawless, and the direction is of a filmmaker who is mastering every finite detail with such delicacy. In the end, Phantom Thread might not be saying quite as much as my next entry, but I’ll be damned if I’ve come to realise it.

2. Roma

Like Phantom Thread, Alfonso Cuaron’s Roma is not above artifice. Every shot looks like it is set up for a protracted I Am Cuba-esque tracking shot and there are truly breathtaking moments of spectacle and force majeure. What makes Roma beyond a social commentary caught within a technical exercise is Yalitza Aparicio as the heroic character at the centre. She is a sizable part of the bravado on display.

3. Leave No Trace

The compassion of Leave No Trace is largely down to the two lead performances. However, I would also add that Debra Granik has a natural way of managing to successfully capture the plight and hardship of outsiders finding their way (such as she did with Winter’s Bone). Nothing is overdone, but everything is heartfelt and done with a tremendous sense of humanity. We feel the pair’s sense of frustration in trying to adapt and cope.

4. Burning

I’m still pondering whether the film found a satisfying ending. If, eventually, I find out that it did; then there is no question that Burning is my film of the year. The film is a beguiling portrayal of male toxicity and social inequality, which then spears itself into a murder mystery. At times, Burning takes on a ghostly form, and just like the female subject at the centre of affection, is dancing and then wisped away.

5. Eighth Grade

At the beginning of this year, Brad’s Status presented social media angst in the form of a 40-something year old man. Eighth Grade, also takes aim at this subject with an insecure girl at the tail-end of middle school. Newcomer Elsie Fisher (a real find), portrays the eighth-grader whose anxiety attacks, her will to please, and embarrassment hits right on the nose. The film’s pain is matched with sensitivity. To put it another way, you want to be the father who tells her everything is going to be alright.

6. Zama

Watching Zama is like experiencing a fever. Director Lucrecia Martel adds that layer of deterioration through strange visual intrusions (mostly animals) and a soundscape which burrows into our heads. Just like the titular corregidor destined to be chipped away by his surroundings. Perhaps it is because of the arrogance of colonialism or of one man whose one act of voyeurism seals his fate.

7. You Were Never Really Here

As much as Lynne Ramsay is rightly admired as one Britain’s greatest directors, she is surely one of the most truly balls-to-the-wall. You Were Never Really Here is about insanity and trauma. Two themes you would’ve thought would be clumsily trivialised in a revenge drama, but in this case it is sorely felt and then some. Bringing it home is a sympathetic and devastating performance from Joaquin Phoenix.

8. 120 Beats Per Minute

What 120 Beats Per Minute manages to achieve is the bold hop-skipping between the urgency of a group of activists debating in a lecture theatre, and the exhilaration of fun time (dancing in nightclubs, joshing on the subway) and blooming relationships. These two areas bolster the film’s commitment to showing a very human side to AIDS activism: romancing the romance, not the epidemic.

9. Sorry To Bother You

Boots Riley’s lip-smacking Sorry To Bother You is like a fantasia of satirical genres; it doesn’t matter if it doesn’t manage to hold together all of the time, what matters is that the ideas are presented in crackling fashion and it is not afraid to swerve at a moment’s notice. Sorry To Bother You makes no bones about being wicked and loud. On the contrary, this is a satire that is unapologetic in bothering you.

10. Widows

Widows is a film of heartbreak, uncompromising attitudes, and grief. Hard to believe you can fit all this in the template of a heist thriller. Perhaps riskiness is not enough for some, but through some cleverly mastered shots, nail-biting interactions, and a brilliant ensemble cast, a few contrivances can be forgiven. Typical, then, that Widows will be passed by the wayside come award season.

#top 10#Top Ten#best films#2018#roma#leave no trace#widows#burning#you were never really here#zama#sorry to bother you#120 beats per minute#eighth grade#Phantom thread

1 note

·

View note

Text

Mid-Point: My Top 10 Films of 2018...So Far

1. Phantom Thread

Frustrating to have to succumb to Paul Thomas Anderson once again, but no film so far has been as well-crafted as Phantom Thread. I will also push for the fact that, if indeed he has chosen to retire this time, this is Daniel Day-Lewis’ best performance. Or, more accurately, I find this one to be his most satisfying. Beyond Phantom Thread’s nuances, it is a film which dexterously explores passion, vexations, and the sublime environment.

2. Zama

The top three films share a common hypnotic vision, which are highly inclusive to the audience. Director Lucrecia Martel creates a trapped and feverish atmosphere where llamas stalk the background and the soundscape pierces the mind like a parasite digging away. At the centre is corregidor who cannot slip the clutches of a Spanish Empire who wants him to remain stagnant. Zama is leisurely, but it deftly crawls underneath your skin.

3. You Were Never Really Here

With a glut of vigilante and gun-for-hire films which look for a blaze of glory and cheer, You Were Never Really Here opts for devastation and trauma. All of which is anchored by an earth-shattering performance by Joaquin Phoenix. Lynne Ramsay has an eye (Ratcatcher, Gas Man, Morvern Caller) for images which capture disorientation and a blurred sense of loss for what has gone before. Broken worlds don’t come harsher than this.

4. 120 Beats Per Minute

Winning the coveted Grand Prix at Cannes last year, 120 Beats Per Minute is not so much about HIV and AIDs as it is also about movements. How protests are clearly thought and approached against their anarchic sensibilities. Interspersed are exhilarating nightclub sequences, personal affections, and anger. Most of all, it expresses a sense of community.

5. Brad’s Status

Ben Stiller has chosen some incredibly well-suited films over this decade (While We’re Young, Greenberg, The Meyerowitz Stories), but Brad’s Status moved me a little bit more. Maybe it is the enduring and excruciating way that white middle-age angst is portrayed, or that it ends on a note which provides much sweet optimism in a way which wasn’t too hoary. Better yet, it confronts a lot of our fears about comparing our everyday lives with others.

6. Loveless

Director Andrey Zvyagintsev doesn’t give us any more reasons to be cheerful. Loveless is full of people devoid of happiness or joyful union. Instead that union only comes together at a tragic price: a boy running away from his home and into the wilderness to get away from his parents’ brutal separation. Whether you take that as a testament to a fractured society is up to you, but the gut-punch stays for a while.

7. Black Panther

The timely cultural aspect of Black Panther can be put aside for the moment, but out of all the Marvel films this ranks near the top. And it takes the bloated and over-stuffed Avengers Infinity War to realise that Black Panther was remarkably un-Marvel like. Strong villain, strong morals and traditions, and scenes which provided more vim than many blockbusters at the moment.

8. Tully

It’s a crying shame that not enough was being said about Young Adult back in 2011. With Diablo Cody, Charlize Theron, and Jason Reitman re-united, it seems like Tully will pass by in similar fashion. This time, Theron plays a mother struggling from the over-exhaustion of having to tend to three children. Well-written and performed, Tully is funny and candid about maternal panic.

9. A Quiet Place

Between the horror breakouts of A Quiet Place and Hereditary, I found the former slightly more consistent in its effectiveness. Given, it is an effective tool used confidently: no noise must be made, that’s how they find you. A Quiet Place knows how to taunt your sensitivity to sound, and it’s not above making sudden jolts of noise. However, it’s hard to deny the value of those scares.

10. Ready Player One

Two Spielberg films were released this year: the newspaper drama The Post and game-fantasy extravaganza Ready Player One. The first film had more prestige, whereas the latter was criticised for being long and indulgent. But you know what? I’d rather have fun and be dazzled by Ready Player One with all its length issues and contrivances, than having to watch a respectable but slightly unremarkable Oscar-nominated drama.

#top 10#film#movies#2018#phantom thread#zama#ready player one#a quiet place#tully movie#black panther#loveless#brads status#120 bpm#you were never really here

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Slap On The Wrist or A Pat On The Back: The 90th Academy Awards

The Oscars is, in a way, a perverse thing to follow. If you are serious about film then you know it’s not good for you. Yes, the politics. Yes, the tackiness. Yes, the phoniness of it all. However, the Oscars feed my unbearable smug sense of opinionated satisfaction. Like the Grammy’s, the Oscars usually pick winners according to their populist appeal, or who Harvey Weinstein happened to lobby for. But then again, the mood has changed and the self- congratulatory tone of Hollywood is under more scrutiny than it arguably has ever been. It’s not going to be enough to throw around a Kevin Spacey joke, there is going to have to be a careful acknowledgement about what needs to change.

Whilst that is going on, I would like to provide a quick throwaway roundup of this year’s main categories. The focus is on the big six – Picture, Director, Actress, Actor, Supporting Actress, and Supporting Actor. Unfortunately, the awards are set to a US release schedule. So whereas I’ve seen Loveless and The Square, I haven’t seen the three other nominees in the Best Foreign Language category.

Best Picture

Ever since the Academy decided to increase the nominees from five to nine or ten, there has been a greater chance to pick a number of films which don’t belong. Thank goodness there is only one this year: Darkest Hour. A broad historical drama which looks more suited for the BBC Original Drama slot on a Sunday evening. The other nominees range from timely offerings (The Post, Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri, Get Out), tender coming-of-age (Lady Bird, Call Me By Your Name) and filmmaking masterclasses (Phantom Thread, The Shape of Water, Dunkirk).

The gist is that this is between two frontrunners: Three Billboards and The Shape of Water. My personal gripe is that Three Billboards has been misconstrued as the ‘transgressor entry’ this year. Unlike what many commentators pointed out, I don’t think its attitude to race is the problem. The problem with Three Billboards is that too often, it likes to eat its cake. Too bad, because it has a message worth exploring. Instead, I think Get Out should’ve taken the mantle. It has more bite and wit to its social commentary, as well as being devilishly funny.

Three Billboards has dominated the Golden Globes and the BAFTAs, but I have a feeling The Shape of Water will edge it. It won at the Producers Guild Award for Best Film – which is usually a solid indicator for Best Picture – and lets not forget how we all thought La La Land was going to sweep the board

during award season, only to be pipped to the post by Moonlight. The point is the Oscars haven’t always been complicit with its forerunners.

If there is any outside heat come the night, it will most likely come from Lady Bird. My personal picks are split into two categories: the Best Film and the Defining Film of the Year. The exquisite and thrilling Phantom Thread for the former, and Get Out for the latter. Academy voters, if you want to make a genuinely interesting and deserving pick, pick Get Out.

Will Win: The Shape of Water Should Win: Phantom Thread Missed Out: The Florida Project

Best Director

One cannot put a finger wrong with the nominees in this year’s director category. Whatever you may think about Dunkirk – and it admittedly did leave me a bit cold - it has been directed within every inch. Christopher Nolan’s time will undoubtedly come, but he was just shy of making a truly great film. Plus, he has got to contend with Guillermo Del Toro for The Shape of Water. It’s hard to ignore the labour of love Del Toro has put into it, even if it’s a sum of a lot of elements he has explored before.

Otherwise, Greta Gerwig does a tactful job of directing the coming-of-age qualities of Lady Bird, and Jordon Peele brings a cracking intelligence to Get Out. The one nomination that niggles me the most is Paul Thomas Anderson for Phantom Thread. It’s probably because he has more discreetness to his mastery compared to the others, but moreover, he is in a different league. Therefore, he has the least chance. Go figure.

Will Win: Guillermo Del Toro (The Shape of Water) Should Win: Paul Thomas Anderson (Phantom Thread) Missed Out: Dees Rees (Mudbound)

Best Actress

For all my doubts about Three Billboards, everyone seems to be in agreement about one thing: Frances McDormand. I will go as far as to say she gives that film a lot more distance than it probably should’ve got. The

closest competition to her is between Sally Hawkins for her dexterous performance in The Shape of Water, and the faultless Saorise Ronan for Lady Bird. Both actors put themselves wholeheartedly behind two very personal projects.

Margot Robbie also deserves plaudits for her ferocious turn in I, Tonya. It’s a performance that is commanding, brimming with energy, but most of all it’s exhausting to take in. It’s a pity she is in a tough company of actors at the top of their game. Save for Meryl Streep with her serviceable presence in The Post.

Will Win: Frances McDormand (Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri) Should Win: Margot Robbie (I, Tonya)

Missed Out: Kristen Stewart (Personal Shopper)

Best Actor

Darkest Hour was built around showcasing one performance, and that obviously was Gary Oldman. So the Paul Newman award for Great Actor- Wrong Film (Best Actor) will go to him without a doubt. Ok fine, I’m being a bit snooty, but I’ll be damned if his Winston Churchill was the most affective performance out of the five nominees. Oldman puts his all into portraying the gargantuan politician, but it’s too tailor-made for the award circuit.

In my opinion, two performances stand out based on skill and insight. I’ll state the obvious: Daniel Day-Lewis is fantastic. More than that, it might be one of the best performances he’s turned in since In The Name of the Father. Better than his Lincoln, better than his Bill The Butter, maybe even better than his Daniel Plainview. The other is Timothée Chalamet for his part in Call Me By Your Name, which exudes intellect and heartbreak.

Will Win: Gary Oldman (Darkest Hour)

Should Win: Daniel Day-Lewis (Phantom Thread) Missed Out: Robert Pattinson (Good Time)

Best Supporting Actress

Again, it’s another tough category full of impeccable acting. I’d like to think this is as close as it was a month ago, but after the BAFTAs it looks like

Allison Janney will win out. Make no mistake; she brings out the toxicity as Tonya’s mother in I, Tonya. It’s a role so loud that it casts a shadow on the rest. Laurie Metcalf is wonderful as an exasperated mother trying to bring out “the best version” of her daughter in Lady Bird. Pretty much the central mother-daughter dynamic is what makes the film work so well. I think the Academy will underestimate that.

Out on the left field, Leslie Manville is on sniping form as a lurking overseer in Phantom Thread. It’s this years Mrs. Danvers. Octavia Spencer has a more grounded presence in The Shape of Water – which is much needed in retrospect. Finally, Mary J. Blige gives an impressive performance full of motherly strife in Mudbound.

Will Win: Allison Janney (I, Tonya) Should Win: Laurie Metcalf (Lady Bird) Missed Out: Tiffany Haddish (Girls Trip)

Best Supporting Actor

The presence of two supporting actors from Three Billboards, hammers home my earlier point about actors propping up a meretricious script. Sam Rockwell injects a captivating layer to his character, and Woody Harrelson is perfectly droll. This only leaves three other nominees. Christopher Plummer’s nomination is more like a frank acknowledgement for stepping in at the last minute (he replaced Kevin Spacey), and Richard Jenkins plays his role in The Shape of Water in a delicate manner.

However, this should be Willem Dafoe’s year. Not many American actors commit themselves in switching between mainstream and art-house, on a regular basis, quite like Dafoe. Whether it is European cinema (Pasolini, Antichrist, The Dust of Time), American Cult Cinema (Wild At Heart, Auto Focus, American Psycho) or Blockbusters (Spider-Man, The Fault In Our Stars, Speed 2). Need I say more? As a stringent, but caring janitor in The Florida Project he blends excellently into the flaky backdrop of a motel.

Will Win: Sam Rockwell (Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri) Should Win: Willem Dafoe (The Florida Project)

Missed Out: Hugh Grant (Paddington 2)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Netflix Roundup - Christmas 2017

Love, Actually (15, 135 mins)

Love, Actaully is a festive blancmange, and not necessarily in the worse way. This is what makes reviewing it incredibly frustrating. For every tacky Hugh Grant skit and a horribly misjudged opening narration, there are some funny moments and a truly heart-breaking scene with Emma Thompson, which still makes me tear up.

3/5

Arthur Christmas (PG, 97 mins)

It wouldn’t be fair to compare Arthur Christmas with previous Aardman offerings (it’s just a notch above Flushed Away), but it is an above average Christmas animation. Arthur Christmas has a witty and, although not wholly original, a warm sensibility.

4/5

El Camino Christmas (15, 89 mins)

As jet-black Christmas crime movies go, El Camino Christmas yearns to have the cynical wrapping of festive films like The Ref, Trapped In Paradise and Bad Santa. Instead, it comes off like a carbon copy. Also, Tim Allen is perplexingly miscast as a drunk and abusive Vietnam vet.

2/5

A Christmas Prince (PG, 92 mins)

The other Netflix Original offering is one I cannot even imagine harming an atom. A Christmas Prince is no more than a little Hallmark movie, which belongs to the overstuffed made-for-TV genre of Average-American-Girl-Falls-For-European-Prince (A Princess for Christmas, A Royal Christmas, the Prince & Me movies).

2/5

Scrooged (PG, 101 mins)

If you have Bill Murray in your film doing his shtick, you’re usually already halfway there. Scrooged may be a bit clunky and crude, but considering how tawdry the concept of a modern-day Christmas Carol could’ve been, the film still manages to have a little bite to offer. Again, that’s mostly down to Bill Murray.

3/5

A Christmas Horror Story (15, 99 mins)

As a quartet of horror threads cantered around Christmas, A Christmas Horror Story takes a little bit of this and little bit of that. It has nothing any hardened horror fan hasn’t seen before, but it is affective in a passing sort of way, and has a bloodthirsty Krampus tale to boot.

3/5

Christmas Inheritance (PG, 104 mins)

If frothy and light is what you want out of a Christmas film, then Christmas Inheritance will probably do. You can pretty much connect the dots: city socialite is sent out-of-town to wrap up family business, she hates the quaint little town, but eventually finds love in unexpected places. Blegh or meh, take your pick.

2/5

Deck The Halls (PG, 93mins)

I was never a huge fan of National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation, but I will hold it close with a thankful heart if Deck The Halls is brought at the table. It has all the jokes Christmas Vacation had, if the groan meter was ratcheted up to laborious levels. The worst of Deck The Halls is that it is truly heartless.

1/5

#netflix#christmas 2017#christmas#christmas prince#scrooged#love actually#arthur christmas#el camino christmas#reviews

0 notes

Text

My Top Ten Films of 2017

1. Moonlight

Moonlight is really something to treasure: possibly the best Best Picture in the Academy’s questionable history. The Oscar hoopla aside, the film has a vibrant and lyrical understanding of race, coming-of-age, parenthood and masculinity. Rarely does a film encompass all themes with such affection, but Moonlight is worth its stamp in film history.

2. My Life As A Courgette/The Red Turtle

If you were in the UK earlier this year, you would’ve been lucky enough to have the opportunity to catch a double bill of two sublime animated films. And you could see both in under two and a half hours. Every bit of that time is a bold display into what animation has to offer. My Life As A Courgette is a careful story on the rehabilitation of child trauma, and The Red Turtle features breathtaking visuals that almost belong on a canvas.

3. Toni Erdmann

Not escaping the earlier part of this year, Toni Erdmann sounds way too tacky to work: a two hour forty minute comedic drama about a father who goes under the guise of a buffoon, in order to save his daughter from corporate soullessness. What director Maren Ade manages to do is miraculously avoid the mawkishness, which could’ve easily made this film destined to fail. It’s remarkable that it doesn’t. Toni Erdmann is genuinely funny and crushing when it needs to be.

4. Call Me By Your Name

As much as Call Me By Your Name might be guilty of being too handsome in its exposition, it is also a film which soaks in. Whether it is the lush scenery, the piano-spittled soundtrack, or the moving performances (in particular, a star-making performance by Timothée Chalamet), it is a poignant film for which its intelligence is never testy.

5. The Florida Project

Director Sean Baker effectively carries his observations of individuals on the fringe of society into The Florida Project. What makes it accomplished is the ravishing cinematography, which captures Kissimmee as a playground full of beautifully garish motels, and the seamless mix between established actors (like Willem Dafoe) and discovered talent.

6. City Of Ghosts

Morbidly, there are many horribly enlightening documentaries coming out of the woodwork about Syria this past year. From Sebastian Junger’s Hell on Earth: The Fall of Syria and the Rise of ISIS to the searing Last Men in Aleppo, all of them have their place. City of Ghosts is a draining watch. It unflinchingly captures the trauma of a country and the resident journalists having to sift and endure through one calamity after another. Essential.

7. The Happiest Day In The Life of Olli Mäki

You wouldn’t really be at haste to ask for another film about boxing (especially when it’s in black-and-white), but The Happiest Day In The Life of Olli Mäki is a charming and wonderfully offbeat addition to the genre. Without cliche, it’s the best kind of underdog movie: one with a genuine dose of humanity.

8. Blade Runner 2049

It may take a while to sink, and somewhere further down the line it might be considered one of the best sequels of all time. However, for the moment, Blade Runner 2049 is never short of what it means to be a science fiction film with spectacle and ideas . Even if some of those ideas fall a bit short. To follow on from the prestige of Blade Runner, with even a trace of honour, must be worth something.

9. The Work

One of the most riveting documentaries this year is set in Folsom State Penitentiary, and focuses on a program set up to offer therapy sessions to inmates. It’s as intense as you can imagine; here men are unravelling their intimidating appearances to talk about depression, parental issues and addiction. Whatever way you look at it, expose like this is fascinating.

10. Raw

Not so much a film about cannibalism as it is about sisterhood, identity and (again) coming-of-age. Raw is a delve into the horror of initiations and trying to find a sense of belonging. Ultimately, despite its fiery provocation, it’s a film which cares about its central characters and it’s hard to ignore.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

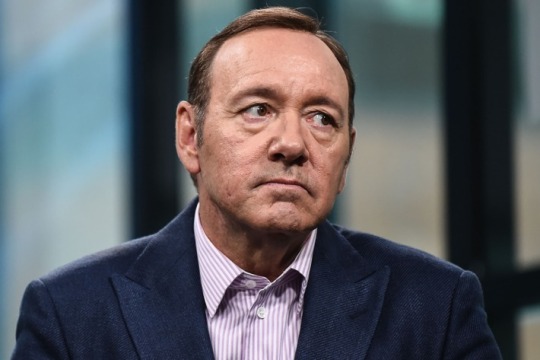

No Heroes Left: How I Was Fooled by Kevin Spacey

He’s plastered on my wall, he wrote me a letter to say thank you, and I saw him perform on stage. To have your hero disgraced is to almost hear him deceased. And rightly so. My sense of utter betrayal and unmitigated anger will never match those who were abused by Kevin Spacey. I’m even starting to think if eulogising the man is a good idea, but it’s a good lesson in how idolisation can destroy your perception and feed their image. Congratulations Mr. Spacey, you made me feel like an outright fool.

Fans of Kevin Spacey, like me, were seduced by his magnetism. A magnetism which was not so much through versatility, but by his own persona. It’s how we all identified him: the lather-like voice, a snide head-tilt now and again, and a commanding theatrical presence which yelled, “Look at the professional!”

Looking through the allegations thus far, the narrative is painfully there: a young person looks up to Kevin Spacey, Kevin plays with his own standing in the industry, plays out the slippery act, then he just can’t help himself. The Anthony Rapp allegation took place in 1986 (the year Spacey got his first significant film role as a mugger opposite Meryl Streep and Jack Nicholson), and the latest allegation being July of last year. But hey, why does your conscience need to kick in if no one has found out? For someone predatory, like Spacey, it’s not about reflecting on the reprehensible actions. The sadness at looking at this from someone as ignorant as I am, is in looking at some of the roles he performed throughout his distinguished career. I was foolhardy enough to trace a faint association between his characters and a charismatic man.

How could I be looking at the man who brought to life St. Jack Vincennes on screen? It’s possibly my most favourite role of his. L.A. Confidential is a film I watch each year before Christmas (as the first act is set during festive season). There is one scene where once an up-and-coming young actor - who was earlier in the film busted by Spacey’s Vincennes - is broke after his arrest. He is brought before Vincennes at a high-ranking party with a proposition by slimeball rag-gossip journalist Sid Hudgens: the kid will be paid a measly sum to perform oral sex on the District Attorney. The pivotal moment in L.A. Confidential strikes a dagger through the bravado of Vincennes. In the midst of an awkward conversation, he knows the kid is about to be sent to the dreck of Hollywood’s seedy exploitation:

“You know, when I came out to L.A., this isn’t exactly where I saw myself ending up”

“Yeah well...get in line, kid”

This scene ends with Jack hesitantly taking a $50 from Sid Hudgens to stay quiet and bust the young actor in the act. Next is a scene which gets to nub of my conflict in watching Kevin Spacey on screen now. Jack is having a stiff drink in the Frolic Room on Hollywood Boulevard. In a brilliant moment of crisis of conscience, Jack is sitting at the bar staring at a forlorn, sack-of-shit, half-drained reflection of himself. All the while, Dean Martin’s “Powder Your Face With Sunshine (Smile, Smile, Smile)” is cruelly playing in the background. Jack takes a moment, ponders his payoff $50 bill, and then decisively takes off without finishing his shot of whisky. Unfortunately, he’s too late and before he knows it finds the kid murdered in the motel.

The rest of the Vincennes strand is not just about him trying to find justice for the kid, but it’s also about redeeming himself. Kevin Spacey is playing a character in blissful compliance, who hangs onto the glamorous side of fame, has his sham and boastful exterior peeled back, and eventually tries to do the right thing. The last two points are a bitter and hurtful contrast to what we now know.

Then we need to talk about his ideals up to the point of the revelations. He famously said, “the less you know about me, the easier it is to convince you I am that character on screen”. Fair enough. Unlike many who pushed in the press to out Kevin, I was never bothered. It seemed clear from the outset that he was never going to come out easy, so why try? Is it our business? All I wanted to hear was his goodwill toward fellow actors and actresses. He stated that one of his most personal affinities was with Jack Lemmon, who got Kevin’s start in Broadway and taught him to pass the buck should the time arise. Kevin co-starred with Jack in the revival of Long Day’s Journey Into Night, at the same time the alleged abuse began - in 1986. It’s hard to grasp what would’ve been a sublime watershed moment for Spacey, it occurred at the same time he decided to make non-consensual advances toward a fourteen-year-old.

Kevin was never shy to present himself as a man of theatre. Imagine my excitement when I was fourteen. I was walking toward the junction of Waterloo Road and The Cut. My uncle pointed at The Old Vic and told me Kevin Spacey was about to become the new artistic director. Suddenly, the location lifted above the ground and felt the like centre of the world. My hero, Kevin Spacey, was only a commutable distance away. I remember sitting in a cafe on Baylis Road, not even half paying attention to what my uncle had to say. I kept staring at The Old Vic.

The next year, I was able to watch Kevin Spacey for the first time on stage. He was acting in a little play called National Anthems (American Beauty-lite). Arriving at The Old Vic gave me the most severe case of butterflies. The pedigree and aforementioned magnetism of the man was too much to handle before the curtain rose. I couldn’t lend an ear at that moment. At this time, I probably doubt I could love my mum as much as I could love Kevin Spacey. When he took to the stage, it was distracting. Instantly looking at the flesh of your idol, and in my mind I started cataloguing his screen roles. It was his screen material battling against his physical stage entity. It was fascinating.

Afterwards, I went home with an almost devout admiration for Kevin Spacey. He even took the time to sign autographs at the stage door. As his tenure at The Old Vic wore on, I saw him in more productions such as The Philadelphia Story, Richard II, I saw him return to Eugene O’Neill in A Moon for the Misbegotten, and David Mamet in Speed-The-Plow. I even went to see Robert Altman’s bash at Arthur Miller’s Resurrection Blues - a production so barbed with bad reception, it was closed after just three weeks.

When Kevin’s incumbency came to an end, he raised The Old Vic from a marginal theatre south of the Thames. I felt a sense of pride, and slight smugness against the naysayers. Granted his stardom brought more punters, but so be it. Especially when the competing theatre is the National just a few blocks away. He popped along to acting workshops ran by the NYT, he went on Parkinson (our premier talk show at the time) to promote theatre as being like watching a sport, and he had his own foundation to support talented young actors.

As time wore on and as I climbed out of adolescence, my Kevin Spacey fandom gradually became more muted. To me, Kevin was more of a showman and his shtick became less to marvel at. Nothing quite matched his enigmatic and cool characters in the Nineties. One of my favourite films is Seven, and I’ll never forget his entrance: he practically shouted at the top of his lungs that he arrived on screen. He lived up to the exceptional and tactile craft of that film. But maybe that’s what happens when you grow up; you tend to get these sorts of affections towards your idols, and then have a reality check.

However, it did not escape the influence Spacey had on many people like me, and unfortunately to those who had stayed silent for too long. I cannot imagine how devastating a sexual violation must be, at the hands of someone we thought we could respect. And of someone who had the gall to try and play his “coming out” as being connected to his predatory behaviour. As many commenters have already pointed out, this could only serve as fuel to the bigoted myth that gay people are sexual predators.

This, above all, is our own doing. And, admittedly, my doing. We’ve let the victims down. Back in 2005, Kevin filed a false police report that a mugger in Clapham Common assaulted him in the early hours. Before the metropolitan police were about investigate, he later changed his story to that of ‘he tripped over his dog’. I remember people telling me this sounded dubious. After all, Clapham Common has a reputation in the community for men exchanging sexual favours. He might’ve been embarrassed, but why was he quick to change his account? Was there shame? Maybe it was something else. After what we’ve heard, who’s to say he was the victim? At the time I didn’t want to hear it; because heroes don’t lie, they’re not amoral, and they don’t prey.

It’s worshiping heroes that set us up for crushing disappointment. We see it everywhere, and with social media we can get our undies in a twist loud and proud. My attitude was the reason why it took long for someone to pluck the courage, and peel back the illusion that Kevin Spacey is an extension of his mesmerising characters. As I type this, a breaking story has popped up that twenty people have now testified that inappropriate behaviour occurred frequently at The Old Vic. Of course every new detail is a blow to what I thought I believed in, but at the end of the day, I’m glad this is happening. Stardom should never, EVER be a tool against anyone too intimidated to raise their hand. This is a long time coming for the victims. If we think our sacrifice is grave, beg to think about the person who is trying to quell back the tears at night, staring at the ceiling, alone in the world. All the while, Kevin Spacey chucks the script and waits finish his shot of whisky at the bar.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Oscar Predictions 2017

Another year, a different political landscape and an exceptional set of films. At the end of the night, I believe La La Land’s technical wonder will bring in a hefty haul to rival Titanic and Lord of the Rings: Return of the King. That aside, I have to admit there are some categories I cannot summarize due to the usual hindrance of having films released yonks after the award season. Specifically, the Foreign Language category: I confess to only having seen two out of five (Toni Erdmann and Tanna), and Animation, three. Having said that, the former is likely to be a battle between the miraculous Toni Erdmann and Asghar Farhadi’s The Saleman – which has had a political boost, due to Farhadi being refused entry in the US.

BEST PICTURE

Out of the nine nominees this year, seven of them are stellar enough to make the shortlist. The other two? Fences and Hacksaw Ridge were not bad, but they had glaring weaknesses. Fences stubbornly refuses to allow much cinematic licence and Hacksaw Ridge has a soapy first half against a balls-to-the-wall second half. If I had my way, I would have happily replaced them with Whit Stillman’s droll adaptation of Lady Susan, Love and Friendship, and Andrea Arnold’s breath-taking epic, American Honey.

There is little doubt that La La Land will win the day. In a sense, it already has, ever since it premiered at Venice last year. It is a film which hooks you with a seductive and all-too crafted postcard of Hollywood. If anyone is to give La La Land a self-congratulatory hug, it will be the Academy. My personal thoughts on the film do not reflect the ravers or the detractors. It is a film which is beyond flaw in the first half, slags a bit in the second, and comes around in the final act. Yes, La La Land is a hip little busker with shiny shoes, but it is hard to not appreciate some of its spectacular moments, before we have that lecture on how jazz is being killed by blah-de-blah. In other words, I cannot bring myself to be that smug and say, “It’s overrated”.

If I have a flag to fly, I fly it wholeheartedly for Moonlight, which I’ve been banging on about since I saw it in New York. It is a remarkable film combining the gritty social realism of suburban Miami with strong trance-like tones which transcends Moonlight into a fleeting piece of work. My second place prize would go to another film dealing with a masculine crisis, and that is Kenneth Lonergan’s carefully written and expertly performed Manchester-by-the Sea. Having said that, I doubt you’ll see a more sensitive and touching film than Moonlight this year. It’s a shame it will be trumped by La La Land, but then again Boyhood was trumped by Birdman a couple of years back.

Should win: Moonlight

Will win: La La Land

BEST DIRECTOR

Barry Jenkins should win for Moonlight, but this is pretty much in the bag for La La Land’s boy wonder: Damien Chazelle. This is classic case of tactfulness verses craftsmanship and La La Land screams ‘craft’ whereas Moonlight has careful brush strokes. Elsewhere, Mel Gibson has got his pat on the back, Denis Villeneuve will win another day, and Kenneth Lonergan is more likely to have a better chance in the writing category. Gibson aside, it is a solid group directors on top of their game. Pity we couldn’t get Andrea Arnold for American Honey.

Should win: Barry Jenkins for Moonlight

Will win: Damien Chazelle for La La Land

BEST ACTOR