Photo

Apologies to whoever wrote this. Found in a Goodwill book.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alligator Pears

We were supposed to meet here. I have walked across the lake to this island where Andre’s cabin puffs chimney smoke into the gray sky, I have walked this water before. The lake had groaned below me as I made tracks in the snow. The hatchback was down a fire lane that had last been used maybe a month ago. The water was beginning to run through culverts, but there was still a lot of snow in the woods. There were no wildflowers. Nothing green, other than the firs.

The winter sky had begun to distinguish itself from the rest of the landscape: the still, pale trees. The flat canvas of ice. Now, there is only a small window of time when one should walk on a lake. A few decades ago, I could have driven out here. In April.

When I arrive, his cabin is empty, but a fire burns white in his old iron stove. I set my bag on his low, springy cot and sit at the small bachelor’s dining table. A bit of white powder incriminates a clipboard that pins down a sheet of notebook paper, blank except for some dark stains. I forgot my cell phone, of course. I remove my boot, my sweaty wool socks. It’s almost too warm. I imagine now he may have dropped through the ice, his own cell buzzing away in the frozen depths, waking the fish.

We were supposed to meet here. Andre is my go-to guy for a lot of things. He has blue tattoos on his knuckles and he’s tall and skinny and dresses like he lives in a sewer. We met many years ago, before the border closed. He has always been an entrepreneur of markets untapped. I originally met him when he was a photographer on a dried-out farm on the West coast. Things have gone downhill for him, but they didn’t have too many other places to go. On the wall is a poster: a bright illustration of a young mother with a black bandanna below her eyes and her baby’s mouth at her breast. Painted on the wall’s raw wood is a lime that is more egg-shaped than anything, covered with splotchy black dots and painted the wrong green.

A stack of black spray painted five-gallon-buckets leans against the wall.

There is a tin can on the table with four cigarette butts and a roach. An olive-colored Coleman drains onto the floor. This is where we were supposed to meet. He has the produce. It is getting cold, I feel it all over and all the way through.

It is Michelle who really needs the avocados. “I want some,” she said to me the other day, lying in our bleached sheets. “I haven’t seen an avocado in years. I could get a hooker, a gun, I could still get a gram of coke. but you just can’t get avocados anymore. At least not in the U.S. Nothing grows, and nothing is delivered” She was right, and I just need to please her. If she wants avocados, she needs them. I want her to get big and fat off essential oils. The other night I set my lips on her belly-button, that soft hub of life, and told her I’d call my old friend Andre. He can get these things, he’s in New England.

It had all been arranged. I lift the cover on the pregnant potbelly stove and look at the black logs and feel the blast of heat. I don’t know where Rico gets the things he gets. There are a lot of things people want that have grown harder to find in the past few decades: real cheese, nice clothes, coffee, citrus, real drugs and good songs. I’ve never been much of a reader, but I’ve heard complaints there as well. Michelle bought a gram of matcha, six ounces of pine nuts, and real champagne.

I have to do these things for her, now more than ever. When we first met it was her face. I am ashamed to admit it, but at the time I was interested in little else.

Her black and symmetrical (almost mannish) brows, and her washed-out blonde hair. After we moved in together I realized she did nothing to maintain her eyebrows, and it was all the work of a higher power.

I grope the avocados. Four are very green, one is small and almost black. Andre has left them in astraw basket on the counter. I put my boots back on and go outside. There is a green tarp pulled back to expose a woodpile, and a red tank of gasoline. I see footprints going around the house, but they are filled uo partway with old snow. The sun has set. I think about the ice.

“Andre?” The obvious echo. Andre, we were supposed to meet here.

I can hardly see the lake for the darkness. There are these footprints but I have no cellphone, so I begin to follow them, setting my feet directly within his tracks. We always met in odd places: down alleys, in stranger’s basements, in pool halls, parking lots, and trailheads.

“Andre, Andre,” I mutter. I feel the snot freezing in my nose. The pines moan all around me, occasionally shaking off a mantle of snow. Above all else I hope Michelle doesn’t worry and I hope for Andre’s safety.

I recall that my mother always bought avocados, years ago, usually five a week. She told me about how they were called alligator pears, because of their shape and reptilian hide. You used to be able to get them a dollar a piece, or two if they were organic. I brought sixty dollars for Rico. The market we went to when I was a kid had photographs of farmers from across the globe above the bright produce, where a sprinkler system drizzled on the fifteen-minute mark. A blast of coffee-smell greeted you around certain corners. No flowers were ever out of season, and pretty women with dry hair and soft skin tallied our careful purchases. My mom always had the burlap bags and a heavy black credit card.

I see the lake now: its teeming blankness. I stop in Rico’s cold path. It goes a bit further ahead of me over the shore and the footprints set a straight line in the drifted snow, one that heads onto the lake. I can only imagine Rico below the ice, the ink frost-bitten off his brown skin.

Now, he is probably bobbing in that giant frigid womb of lake water, his body awaiting the spoiled birth of spring.

“One week out of the year,” he had warned me over the phone. “Nowadays, there’s only one week you can make it to the island and back. If it cracks anywhere at all we’re both fucked.”

#avocado#shortfiction#writers on tumblr#dystopic#speculative fiction#drugs#fiction#myfiction#lit#literature#shortstory

1 note

·

View note

Text

Seeing Shapes (drafting)

In most games, there is a pattern. Not even like a puzzle, but like on a quilt: all the same thing stitched together, reversed and spread out. I don’t play them anymore, but I used to all the time when I was younger. I played video games that recycled faces and cars and words and signs. I am confident this is the best way I can describe it. The best comparison I can think of.

I do not drive. As a passenger, you learn many things. The luxury of watching the fields abutting the highway. Missing letters from the neon. Signs that flash late. As a passenger, you have the luxury of being irrelevant. Most importantly, you have the luxury of translating license plates. Busting down acronyms and mixings digits.

Today I saw “EVRAFTR” twice. Once on a black sedan outside the supermarket, and then on a blood-red caravan speeding down the interstate. In the end, it was the cars that got to me. I had tried to look in the deeply-tinted windows, but couldn’t even spot the driver.

Madison’s grandfather died the other day. He was a cruel man. I once saw him try to stomp on a pigeon. She went home after the service and I visited her. We talked about a position she was interested in at a company I had once worked for. She has some deviled eggs wrapped in tinfoil, and took them out of the fridge shortly after she put them in.

“My poor Papa.”

“He’ll be fine,” I console her.

“Yeah.”

Madison has a very clean apartment. Her bathroom has gleaming blonde hardwood floors, and two tall windows facing the claw foot bath. There are a few faces in the floorboards. There is one you can see sitting on the toilet. Sometimes I think it looks like a character from some anti-Semitic cartoon. Once, it was a basket of fruit.

#patterns#fiction#myfiction#drafting#clips#shortread#pareidolia#seeingshapes#videogames#first person narrative

0 notes

Photo

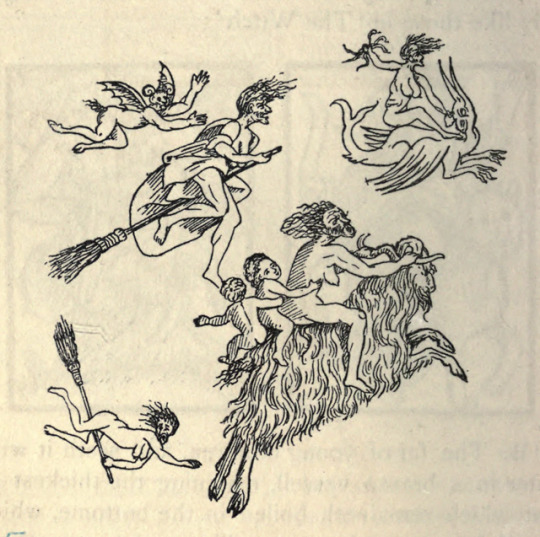

Witches in the air. The Devil in Britain and America. 1896.

11K notes

·

View notes

Text

Pools

0 notes

Text

Fowl

I.

I drove up to a familiar scene. Wooden chairs in the yard, flowers, American flags and silver cloudcover. My cousin is in one of these chairs, poking at a dying laptop. An orange extension cord snaked into the house, connecting back to the charger dangling over her fleshy, flattened thigh.

The house is three stories, not including the basement. The family uses official titles for different branches: the addition, the breezeway, the master bedroom, the patio, the entertainment room. The master bedroom. I’m in the guest room, or the basement, depending on who you ask. It’s the one name they don’t agree on.

My uncle takes pride in the house because he built it himself. When I was younger I imagined him doing everything alone from the ground up. Pouring concrete. Planting the hidden machinery of wires and pipes. Up on the roof, sweating on sunny days, hammering shingles.

It took me time to realize he needed help. He had hired people, and mostly just oversaw the project. It took time to realize he had more money, time, and energy than my father.

“Somebody try to shoot you?” My cousin points to the windshield.

“Of course.”

“Nobody’s home,” she sighs. “And there’s really nothing to do about it.” The clouds move, and the sun finds us for a moment.

II.

The sun was out all day after that. We’re drinking High Life on the porch. My cousin’s wearing a two-piece and I wondered what I’d look like in it. She isn’t thin but she’s healthy and dark. She has thick hips and round arms. She inhabits her body in a way that I, something like a grown woman, envy. She’s the youngest.

“Look,” she says, pointing to the yard. She’s always seeing things I don’t.

“What?”

“A turkey. A hen. Don’t you see it?”

“No, I don’t.” She leans over the railing, looking out over the grass.

“Oh. It’s gone.”

I swallow some beer and take off my dark glasses. I’ve been feeling a certain way.

III.

My aunt and I have the same name, and she left after her fourth son was born. Before this, the joke was that I’d grow up to be like her. Nobody talks about her much anymore, but the boys have when we’re alone. They use the past tense like she’s dead, but we all think she’s in Cincinnati.

My aunt used to write stories and she probably still does. There are copies and notes and drafts on a drive in the office. I read one the other night.

Two foragers are out picking mushrooms. One of them has a growth he’s been ignoring. The other is worried about ticks. They’re stopping at every rotten stump and talking about their lives. The one with the tumor isn’t talking about his medical worries. The one with the ticks isn’t mentioning the crawling in his socks, the tickle in his armpits. They crush through the leaves, snap twigs. They find one that isn’t in the book. It’s a false morel, said the man with cancer. The one with lyme disease shakes his head no: It looks like an ear, he tells his friend. It might be poison, it might be nothing. Unsure why, they pick it and carry on. But it does look like an ear, they both think. Hair even grows out the lobes. Within an hour they have found another ear, lips, a nose. Within another hour they’ve scavenged a whole head.

They divide it down the middle and eat it in a clearing lit by the setting sun, and walk home cured.

Just like her.

IV.

I got sick by June even though it was warming up. I was the one who was cold after all. In my sweatshirt laying on a deck chair I squinted at the sun through my tinted glasses. My cousin was with me, and she wore a gold cross that lay flat against her skin. She looked through a bright flyer from the grocer. I hadn’t gone to her graduation ceremony and she hadn’t gone to mine.

Her brothers and her father were all out working, driving, sitting in trucks in parking lots. She’s asking me about college.

“Do you still have friends? Like, did you lose them?”

“What do you mean?”

She was sitting cross-legged on the porch. Her dark hair was twisted up in a thick fist on top of her skull. The paper was flitting in the wind. Out in the yard, birds were picking at the grass and the mud. But they were quiet.

“I don’t know. Did you really learn anything? People say you don’t need to learn the things you do. I know a lot of people don’t think it’s worth it. I don’t see what’s wrong with learning something you can’t use.”

“You’re right.”

“But what did you learn? Do you remember it? You’d have to.”

“I guess.” I started to wonder if I did learn anything. I thought about a course on Disney. I thought about Cather, Conrad, Dante. I remembered watching Fellini instead of reading The Satyricon. Something about algebra. “Yeah, I read a lot. I know things, now.”

“Oh.”

“I took things in, you know? Honestly, I didn’t do all of the work. Nobody does. But I know some things that I liked. I might have been … a different person. That is, if I didn’t go. I wouldn’t know what I know now. Not that I can do anything with it.”

I thought of a friend I had who had fallen in the snow two years ago. She was alone crossing campus, and it was midday. A lot of people were around, but she was alone, and she fell. Someone told me she bled a little into the snow, out of her ear. Was I losing friends?

“So, you probably aren’t interested,” she began. “But do you want to go to a party? It’s a bonfire. People your age will be there.”

“How big is the fire?”

“What?”

“How tall? How wide?”

“Well, we do it in a field. So, it goes up high, and as wide as we want.”

Okay. What time?”

“Oh, later. Like Friday.”

It is Sunday. My cousin always plans ahead.

V.

I had started coughing. Neon dust is coating the cars, the deck chairs, every unmoving thing. Kids in the neighborhood drew on the car windows. A cock. A frown, a smile. Wash me. Pollen blew in through the window over the sink and coated the dirty dishes. I coughed up something a little less bright.

I was up late, reading one of her stories.

The husband of an accused witch – an owner of two cows and a father of seven – provides the court with evidence against her, in exchange for another cow. He says she sat on his chest in the nude throughout the night, her face cratered and rotting. There was a peacock. It scratched and screeched at his cows. It clawed him and the children. The Devil is in the woods, he says. He cries on the stand while his wife sits in silence.

I minimized the draft and went upstairs. I turned on the light and turned it off and took a beer out of the fridge. Do ghosts lived in new houses? Do they inhabit bodies and not homes, and follow you wherever you went? Do you have to die to haunt someplace?

VI.

Before I moved in for the summer, their dog choked in the yard. She was a golden retriever with a patrician attitude and a name I forget. The dog loved bones and rawhide and marrow. She always slept with my uncle. He would grill steaks and give her half. One afternoon toward the end of winter, she tried to swallow a bone. (They’ve told me this story over and over.) They came home and found her sprawled in the puddles, eyes at the sky. She’s buried in the woods.

I walked into the yard and the security light flicked on. There are still bones. They are big and hollow and tall grass has started to grow into and around them. My uncle doesn’t pick them up and when he mows the lawn he rides around them. I grabbed one and threw it beyond the light. I drank the last of my beer and placed it in the pale nest of grass where the bone was. All across the yard I picked dogbones out of the grass, tossing them into the woods, counting. There were fourteen I could find, and one chewed up tennis ball.

I picked up the ball and threw it. The light went off. I waved my arms, but it didn’t notice me. I jumped, and it ignored me. I stood in the dark. I heard a woman cough in the woods. I took a step forward and waited. This is what hunters must feel when an animal freezes up. They can hear a stillness. There is a restrained movement. I sneezed.

Nothing.

I went back inside, and the light turned on as I went up the porch. As I took another beer from the fridge and my uncle came down the stairs in his boxers.

“What the hell were you doing out there?”

“Fresh air.”

VII.

On Thursday afternoon, I went to finish the story about the witch. I looked for the flashdrive, and I couldn’t find it. I thought I had left it on the ping pong table in my room, but it wasn’t there anymore. I asked my cousin about it but she just shrugged. Again, she was cutting coupons she’d never use.

“Look at these deals.”

A stack on the glass table next to her shivered in the wind. She was wearing a thick flannel over her two-piece and a Red Sox hat.

“Watch out.”

She turned just as a gust picked up her clippings and blew them out across the lawn; she chased them to the railing. The sun was shining off her glasses and she blocked the light with her forearm.

“Where did the bones go?” she wondered, frowning.

I told her about the noise I heard the other night in the trees. Without looking back at me, she said it was just the turkeys.

“They sleep in the treetops, you know.”

VIII.

On Friday night we drove out to the party and I told her I wouldn’t drink too much. I could drive us home, I said. The fire was huge. There were cars parked around it with their doors open, bugs drifting in and out. Kids were laughing the dark. The car almost bottomed out as we climbed the hill. She had opened a beer and we sat there, watching everyone through the window.

“It’s been nice having you around.”

“Thanks. I haven’t done much since I got here. But it’s been cool.”

“I know.”

“When was the last time you talked to your mom?” This question had been stuck in my mind. It almost came out in other conversations, while we baked french fries, or talked about the weather.

“I’m not sure. It’s funny.”

“Is it?”

“I guess like, four years. Maybe more.”

“Is she okay, you think?”

“Why would I care?”

“Aren’t you interested?

“No,” she said. “Nope.”

“What if she were dead?”

The windows were rolled down and she reached out, playing with the mirror. “I wouldn’t care. I mean, I don’t think I would.”

“Do you think she’d haunt you?”

“It doesn’t work like that.”

“Why?”

“Ghosts don’t haunt people. They haunt houses or castles. Or forests and stuff. Or lighthouses. Not bodies. Bodies are already ghosts. Or spirits. Like a caterpillar, you know?”

“Do ghosts haunt guest rooms?”

“They haunt basements.”

IX.

She introduced me to some of her friends. A lot of them were older than her. One of them knew a guy from my school, and asked if I knew him.

“Eric? He’s super tall.”

The music got louder, the voices got bolder. I threw my cans into the fire and watched them twist and turn black. The flames were twenty, maybe thirty feet tall. I sat closer to the fire than anyone else and turned back from the heat.

I looked for things in the flames but didn’t see anything. I hoped to see faces, or numbers and letters. There wasn’t anything, though.

One of my cousin’s friends came over and sat next to me in the grass. She had thick eyebrows and short hair, I could see the makeup painting her cheeks in the firelight. She looked nice. We didn’t talk. I breathed in smoke. Over our heads, ashes floated off into the sky. When I looked around for the moon I didn’t find it.

Having some trouble, I walked into the woods to pee. With a hand against a thick tree, I squatted. On the way down my knees cracked. Nothing came out. I heard my cousin laugh and yell out I’m dead.

Finally, it came. When I was done I took a crumpled tissue from my pocket. My pants around my ankles, I heard a cough in the woods. I fell back, ass in the leaves. In my piss. This time I yelled but nobody heard me. The cough came again. A woman coughing, I knew. I pulled up my pants, and rolled over onto my side.

I watched as the thin legs of a hen stalked through the black leaves. Bird feet, something I’ve never felt. Over me, the turkey was gliding toward the field. A cough.

On my back, I looked up as she bent over me, a hood of bright hair dangling in the dark. A bare foot on either side of my head. She looked away, tilted up in the direction of the fire and coughed once more. Her nails are pale green. She wears bracelets that shake and smells like good laundry detergent. I know her from somewhere, I thought.

“You’re okay,” she told me. “It’s fine, it’s fine.”

And I thought I was cured.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Digit

I.

Marie was on the downstairs couch, a game of solitaire unfolding on the coffee table. She had made a pot of coffee midway through The Today Show. She drank it all and chased with a pinch of Antony’s weed. She sat crosslegged, slowly losing to herself in front of the muted television.

The house was remarkably unchanged, but Marie herself was a bit different from the last time she called it home. She was quieter. She had started watching a lot of television, and had begun losing energy she didn’t realize she had. She lost touch with the global tragedies she used to worry about. She didn’t read. She heard only other peoples’ music. She was 27, buzzing on her mom’s couch, waiting for her little brother to come home so she had someone to talk to. She also hadn’t won solitaire in three days.

She decided to clean a dewy-bottomed pineapple. It left a print on the counter from sweating on the granite. She found it was easy to be centered by these methodical tasks. Marie removed the crown. She lopped off the sweet-smelling bottom. The knife had a heavy, professional feel to it. Her parents always liked the finer things. The sticky juices spread out, seeping over, under, and into the teak board.

Time passed. She had expected someone to be home by sundown, but this didn’t seem like much of a possibility any longer. The heat of summer began to die off. She carried a grocery bag filled with the bits of pineapple skin and the spiky green dome out to the trash bins. A recent invasion of fruit flies was attributed to Marie’s laziness and she made sure to be extra clean. Also Thursday was trash day, so she needed it out tonight.

II.

There were tall pines, bare to the top. Like a Christmas tree, teetering. The bins were beside the garage in a latticed alcove. The arbor, her mother called it. The smell of suffocated trash snuck out the lid before she could even open it.

Removing the lid, she was hit: stagnant rainwater, forgotten produce. There was something less familiar, though. What caught her attention was the bag at the top of the trash pile. A plastic take-out bag covered with purple orchids, with scrawling gold type: Thank You! Thank You! Thank You!

She was confused as to how someone ordered what seemed to be Thai or Vietnamese food without informing her. Antony didn’t have the money. Of course, Adrianne would have gotten her food, but then talked about the sodium content. The few leaves that had turned and fallen skittered in the driveway, clacking like dry dice.

A dismal curiosity got the better of her, and she bent into the putrid plastic maw. She tore open the sack, and a corner of a dishtowel stuck out. Marie lifted the bag out of the canister, into the darkening evening. It spun, dangling from the trussed handles. Fully removing its load, she began to discover the red. She reached some parchment paper at the center of the towels, with deep dark stains. She knew it was blood. You! the bag accused.

She heard the imperceptible hum of her mother’s mint-green hybrid pulling up the lengthy driveway. Marie tucked the bloodstained paper wads into the pockets of her sweatshirt, and turned to walk toward those crystal-clear headlights that cut the now fully-realized darkness.

Later on, her mother accosted her while she watched the 6:00 news. “Do you remember those anti-drug commercials, with the girl melting into the couch?” Adrianne perched one hand on her unmotherly hip, titled at a calculating angle. Marie stared at the television.

“You look like that.” She spun into the kitchen. A cork was drawn from bottle of Pinot Grig.

To be fair, she was correct. However, no mother should address her daughter in the way Adrianne had been for the past 27 years. She imagined her making snide remarks all her life, leaning over the edge of her crib and critiquing her large ears and thick hair. What a little gremlin, she’d cackle, tilting back her shock of black hair.

The hard-nosed news caster looked back at her from the flatscreen television set, a blurry cityscape green-screened behind his steely shoulders. “A true tragedy, we can only pray those responsible are brought swiftly to justice.” He looked off-screen, and began to say something else, when the program cut to commercials.

III.

It was a finger. Wrapped in parchment paper, wound up in Williams-Sonoma dishtowels. It was pale, yet bruised. The pale parts were the color of young ginger. The dark was a dirty purple. The finger nail seemed like it may fall off. She held it gently in the lamplight of her bedroom desk, smoke swirling out of the glass pipe she stole from Antony’s room. He hadn’t noticed, and that was a month ago. For the first time in her life Marie was afraid of her mother. Her bedroom, which Marie had not seen the inside of since she returned home, lay at the other

end of the unnecessarily large home. She was probably passed out, alone, in the bed she shared with Saul when he wasn’t away.

Marie ate a chunk of pineapple. It occurred to her that pineapple did, in fact, taste somewhat like a blend of pine needles and apples. She also considered the possibility that Antony was responsible for this. Her head nodded down, her eyelids flickered.

It lay on a meticulously folded edition of The Hartdon Bugle, occupying the spotlight of her bowed lamp. She thought it might at any minute remember where it was supposed to be, and limp off like Thing in The Addams Family, down some dusty black and white corridor and offstage. But it never moved, which is what bothered her most. Marie had always watched movies and television and wondered why nobody had contacted the police, who she assumed would arrive promptly and sort the whole thing before any damage was done. This didn’t make for good television, she knew.

She now wondered, rather abstractedly, who this finger might belong to. The coarse and bloody hairs, gritty with blood and struggle, lay somewhat flat and extremely disheveled. What would lead Adrianne to do this? Was someone else responsible, and if so, why did Marie assume her mother was?

The limp and mottled index finger – or was it a ring finger? – reminded Marie of something she once threatened to do. She had come home to live with her family after she left a man she had been with for five years. “I can do better,” is what she said.

She stayed up waiting for Antony, watching Law & Order re-runs. Each episode began with the discovery of the corpse. Somebody jogging through the park sees a foot sticking out from under a shrub. Some city workers dredge an urban mummy from a storm drain. A man playing fetch with his dog sees it running toward him with a severed leg.

Marie often found herself dissecting plot lines of T.V. shows. Back in Indiana, she was co-owner of a three-person company that built sets for community theater productions. She had always hoped she’d end up working for an NBC show or anything low-brow and high-paying. Many of the sets the company built were for plays in which people were murdered. She had long ago picked up the plot devices. “Let’s get this to the lab!” a tired detective barked down the alleyway.

IV.

A car pulled into the driveway. Self-consciously slow-moving and quiet, as if the vehicle itself were ashamed of being out so late. Antony snuck through a side door, which he closed with a click and a whisper. He must have heard the television, because he came right into the basement.

“Sis.”

“Antony. We need to talk.”

Marie and Antony stood next to the bins. They had disabled the security light, so when they went out to the arbor they didn’t attract any undue attention from their mother. Antony had laughed when she first told him the story, but stopped after he saw it himself. They passed a crooked joint between them, rolling clouds of smoke into the chilly air.

“It wasn’t her. She’s crazy, but …” he shook his head. “It wasn’t mom.”

Marie didn’t say anything, she just nodded. Antony crouched down around the trashcan, shining the flashlight on his phone throughout the gravel and on the siding of the garage. Perhaps looking for some blood-spray, or ransom note, or a wedding band that would solve the whole thing. He pinched the bridge of his nose in an overwrought expression of tiredness and anxiety.

Marie heaved a foggy sigh. “God damn it.”

That night, she wrapped the finger back up in its packaging, and put it in a gallon Ziploc bag, and placed it in the freezer of the mini-fridge upstairs that her mother never used. A hole burned in her gut. She went to bed without brushing her teeth. Her mouth tasted like stale pot smoke and a chunk of pineapple was wedged in her incisors.

V.

The next morning, Marie woke up to an empty house. Downstairs, a cooling pot of coffee waited. A note from her mother read:

Marie -

I made you coffee! Although, if you go for a run (which I pray you do) drink it afterward, in case of a BM. Could you put the bins at the curb? Get Up, Get Out, and GET SOMETHING.

wait until sundown to self-medicate.

– Mother

Friday turned out similar to Thursday. Marie sunk into the couch. Her left eye twitched, and she quickly knit her brow to correct this spasm. These eyebrows dominated her face. Her ex compared them to an actress’s in a way that raised questions. She heard the garbage truck doing its routine outside, and discreetly parted two of the venetian blinds to watch the arm dump the cans into the belly. She sank further into the couch, flexing her softening muscles inside the sweatsuit she wore the day before.

They had a nice dinner that night. The bulbs above the table hung from thick cords attached to the rafters at odd intervals: spreading like the legs of a giant spider. New houses can have ghosts as well as the old ones. They ate the leg of a lamb, smeared with an emerald blend of minced herbs. Marie ate pistachios out of a black bowl and threw the shells on her empty plate.

Antony, regardless of what he did in his free time, was actually a rather diligent student. Marie forgot exactly what they were celebrating, but all three of them were proud of his achievement. At one point Marie watched as her mother’s tight face softened in the lamplight, her elbows resting on the table, her birdlike hands clasped in an unlikely pose. For a moment, she thought she had imagined tears filling Adrianne’s eyes.

“It’s a nice, nice night. I don’t have to worry.”

Adrianne went to bed shortly after letting that one slip.

VI.

Marie couldn’t find the moon. The wind blew cold from the far-off river, booming up through the pines. She looked up, and couldn’t distinguish the clouds from the sky. Depending on where she focused it could go either way.

She was sitting in what they called “Indian-style” when she was a kid. They probably didn’t call it that anymore. Across the sleeping yard, the snuffed security light was unable to betray her cautious movements. She was digging deep with a garden trowel. The earth would freeze up in about a month, so she had to do it now. The finger was in a Mason Jar, floating in a recipe for an all-purpose preservative she found online. She added a few sprigs of dill for a laugh.

Marie remembered burying a cat slightly deeper in the woods when she was seventeen. Adrianne and Saul had helped dig, as she stood by letting out the last of her tears. It was autumn then too, and she remembered the stillness of the pines and the golds and blushing reds of the oak leaves. Frowzy was about to have a bit of company, but just a bit.

She made sure she was right on the edge of the tree-line, at the foot of the sole paper birch, so she could remember the exact spot if she ever had to retrieve it. She caught the sloshing jar in the light of her cellphone one more time, the bobbing finger catching itself in the vortex of dill and brine. She set it gently into the soft, cold crater and began to fold it into the earth. When she was done, she built a cairn. The clouds separated themselves from the sky and exposed her to moonlight.

2 notes

·

View notes