Text

night on the town

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

after three weeks of binging steddie fics to cope with school starting again here is my contribution to the stranger things fandom thank god and also jesus himself for ao3 @written-mishaps @palmviolet @badpancakelol I am going to be so annoying about y’all’s writing and my friends are never gonna hear the end of it

#IM IN LOVE WITH THIS#I CAN'T BELIEVE I'M SEEING IT JUST NOW#AHHHHHHHHHHH#stranger things#stranger things fanfiction#steddie#steddie fanfic#steddie fanfiction#the one in which a time loop is fucking exhausting

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Well I just read the most insanely beautiful fanfiction that simultaneously smashed my heart into pieces and put it back together again. I now refuse to hear any slight hint of criticism at fanfiction being a less valid form of art. Also it’s 3 am.

#this is the best way to enjoy any fanfic#and tyty for reading mine!!!!#i love finding posts like these <33#(...i will eventually read all comments on the fic)#ao3#stranger things#the one in which a time loop is fucking exhausting

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

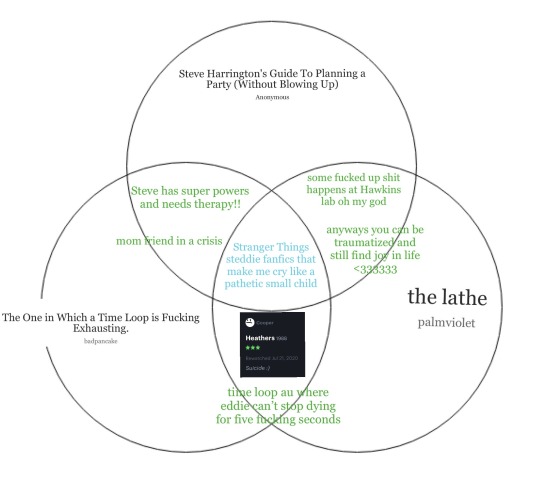

has anyone done this yet lol

#im in love with this#there is absoltuley something going on with us in the stranger things fandom where we just#want to see them suffer#but don't worry!!!#they'll eventually be okay#probably#the one in which a time loop is fucking exhausting

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

holy body

Steve does it, willingly, this time. He doesn’t enjoy it, no, but there were things worse than him. There were monsters that would wear human skin in a way that would make them almost invisible to the human eye, monsters who would speak and talk and move and walk as if they were anything but that — a monster. And Neil Hargrove is one of them. Was one of them.

He doesn’t make it quick. He knows what he has to do, but there are steps that he has to take, this time, to make sure that he is aware, that he is in control, that Neil knows what he did. Steve does not enjoy it, but it is something that has to be done. He drives home and he plans and he waits and he bides his time. Steve watches him — figures out the schedule of Neil Hargrove, what he does when he gets home (drink, watch TV, shout at Max and Billy), when he leaves work. It takes longer than Steve would have liked — planning on how to do this, spending days upon days, a couple weeks, planning. When the time comes, when he finally has everything he needs, when the hubbub of the previous dead body has died down, and his body has been lowered, Steve changes into his darkest clothes, stalks out Cherry Lane, and the Hargrove-Mayfield household.

Waits until Neil Hargrove leaves his house for a smoke.

And then, he lures him.

Steve feels his vocal chords constricting to take shape of those that are not his, that do not belong, but are part, of him. Mimics the sound of laughter, watches as it does nothing. He can hear his own breathing above all else, hot and heavy, and hopes that it can’t be seen in the cool air. Steve tries again — moves his mouth, shapes his lips so that the voice he occupies becomes other, nasally, insufferable, and wholly Billy’s. He’s heard it a hundred times at school. Some people just don’t know when to shut the fuck up. Steve didn’t like him. His father would say that hate is a strong word, do not use it lightly, but there’s just something about the makeup of his face that makes Steve angry. But it does not matter. He didn’t like him, but— this? He watches as Billy’s father steps out of the dull cast of the streetlamps. Nobody deserves this.

He lures him back, watches his steps to keep them, himself, quiet. Steve repeats phrases, what are you, a fucking pussy? Scared? Gonna punch me? Come at me! lures the man deeper into the woods. He watches the way that his mouth snarls, wishes that his hearing would die so that he would not have to bathe in the threats, the crack of his knuckles in glee, the limp in his step from a bad knee injury. He can hear the way that his bones creak against each other tiredly, and it spurs him on. As if they were calling out to him please! Put me out of my misery! Help me! Let me breathe!

It takes a while for Neil to even figure out that something bad is going to happen. It’s… pathetic. Really.

When the trees start to grow dense, and it’s more woods than town, Steve lets his bones shift and form. Does it slowly, lets his legs change, his skin tightening, bones breaking reforming under his skin, ribs shifting to touch each other in harmonious sigh. He lets Neil watch. And he lets his mouth lay closed, lips pressed together, eyes covering up, disappearing, where heat becomes sight and sight becomes nothing.

Steve doesn’t entertain his swears.

“Do you know what you’ve done?”

The man stays silent. He doesn’t even plead in the same way that other worm did. He just stays snotty, and he stays wide-eyed, as if he had been spat on. As if he had someone yank on his front teeth and tell him that they’re ready to be pulled out. Instead, Steve watches as he trips over himself, as he falls back and into the woods — in the wrong direction, in all his haste.

The sound of his shoes against the slippery-leaf floor is exhilarating. He lets his jaw fold and fall, lets his skull bore rot and bone, lowers himself to scratch nails and misshapen legs into a lunge, into a sprint.

He doesn’t make it quick. And he does not have fun. But some people deserved to be hunted.

Scared? Steve thrums, voice garbled and layered under the moonlight. He watches as Neil stops, as he turns to look around himself, to try and find the source. He clambers over, slowly, because he knows that Neil will not get far, and he walks. Steve Grabs Neil’s body by his neck, lifts him like he knows he has lifted others, brings him to where Steve thinks his eyes would be, where they would be if he had them.

Do you know what you’ve done? Steve lets it simmer in the air, lets Neil hear it vibrate through his soul.

He does not answer quick enough.

— — —

When Steve wakes, this time, as he goes to shower to do his hair, as he reaches tender fingers to silk, he feels something that is wholly, and not, him. It protrudes easily from his scalp — sharp shards of bone-wood where his horns would be if he were him. The hot water sprays freckles onto his skin, burns where it once brought comfort.

It shouldn’t be there.

It shouldn’t be bleeding into his everyday life, because it has already ruined enough. Steve had already had to deal with the fallout of what this thing and him, what he, himself, has chosen to do. He does not need it to appear on his skin in the way it does, appear through his scalp, through flesh and blood and bone, as bone.

The tap turns off. His breathing stills.

Don’t let anyone know. They would never understand. Can’t you see what’s happening?

Steam settles on the bathroom mirror. He watches as the silhouette of himself appears. Watches as what is and is not him makes itself scream.

The first thing he does is try and transform. He lets the skin recede, tries to close his eyes and image them to be gone like he had done so many times before. It had worked when he didn’t want to, in the woods that night, and it had worked when he had felt nothing but contempt for the man in front of him. Surely this combination, this prize-pool of information, still applies? He is met with nothing but a strained neck and veins that are all-too human.

And it’s… frustrating. It’s so fucking frustrating in a way that he doesn’t think that he’s ever felt before. Things have never truly gone his way. He didn’t want things to turn out like they have, like they have been. He didn’t want Nancy to leave him in the same way that he didn’t want her to stay. He didn’t want Eddie to hate him in the way that he leisurely conveys to Steve through his eyes and the curl of his lip, the unquestioning gaze that lands where a cut once was. He didn’t want the things in his childhood to end up two they did. With two parents who didn’t really love him, and dreams that make his eyes hazy-wet.

He has never wanted any of this. If he could have it his way, he would curl up into a ball in his room and never talk to anyone ever again. But, no. Nobody would want that, would they? They know woh he is, who he is meant to be, more than he could ever imagine himself.

“Why won’t you fucking help me?” Steve slams his fist down on the ceramic of the sink, watches it splinter. “I do all of this— all of this — and I’m still not allowed to—?”

The voice stays blessedly quiet. Figures.

He tries to smooth his hair over, dries it so that he knows what it will look like. Maybe it won’t show if he styles his hair just right, if he combs over his fringe, if he gels it up, mousses it down, pins it back. He pulls on tufts of hair in vain. Two small bumps continue to be there, glaring and obvious and whispering to him about what he’s done, about what he should do, about what he could do. But he doesn’t want this. He’s used the power that has been given to him, that has been placed on him, but he does not want this. He does not want people to know, or to continue. It was one slip up — a slip up that needed to be done, because nothing else was going to be done, so how was he to turn a blind eye — and it wouldn’t happen again.

It’s not easy — the decision.

He’s always been a little squeamish, trying to avoid situations where people might hurt him, where he might get hurt. Steven hadn’t learnt how to ride his bike until much later than his peers, in fear of scraped knees and burnt hands. The stove was not to be touched until he was left alone to the house, empty and unforgiving. Knives and scissors and sharp ends were tucked away, out of sight, until he could glance in their direction without panic. People would always praise him for it — parents and mothers and fathers — when he would babysit. He would scan the house as if puppeteered, sniffing out glimpses of glinting metal, under the guise of safety for the children!

It’s not that he’s afraid of the idea of pain, of pain itself. He’s been in fights. He’s scratched at his skin till bone would surely show. There are worse things in the world, things that can hurt more than kitchen utensils and a misplaced phrase. It’s just— the idea of what he has to do so that he can continue to keep living how he wants to, continue to live like a normal, ordinary teenager, with his normal, ordinary friends. He doesn’t like it. The idea of it— the image and the sound and the dust that has been kicked away to reveal itself in one horrible, terrible, idea.

Of course, he doesn’t have what he needs. He’s vain, yes, but not this much so.

He lets the light from the window flow into the hallway as he opens the bathroom door. He feels the temperature change between his toes from cold, slick, tile to carpet with— not crumbs, because they would never allow eating anywhere that wasn’t the kitchen— but the musty feeling of matted nothingness and age. The hairs on Steve’s skin pricks up, flows down his arms and chest in little bumps, unaccustomed to the cool air. One foot in front of the other, he lifts and walks down the hallway, passed the windows that look out onto the woods. In this way, it has been decided.

The door in front of him is fifty miles tall. It grows and it grows, and it feels as if he is only small, again, just tall enough to reach the handle. He is not allowed to knock. He is not allowed to bother them. He is not allowed to enter. It does not matter that he is tall enough, that there is hurt. He is not allowed.

But it needs to be done. He needs it like he’s never felt need before — as if what he thought was love was just lust and the want for companionship, the want to feel skin against skin, the want to feel love so much that he tricked himself into thinking that anything and everything was just so filled, that he had loved them. It is not the want that he thought was need. He can live without the want. He cannot live without this.

He lifts his hand, outstretched fingers delicately pressing themselves into the metal of the door handle. Steve enters the room, dust covered skirting boards and side tables turned to look at him, exaclty how they left it. Nothing has changed, no blanket untucked, or a pair of shoes missing. He can see from the doors the loose hairs from where his mother would brush hers, long strands stuck near the vanity. Her makeup will be long expired, now, perfumes gone foul and sharp. Steve does not look for his father’s memory.

It’s as if there’s something stopping him from entering. But what Steve needs is in here. He cannot stay on the outskirts forever. He needs to dive in.

(His heart beats against his ribs, once and once and once again. He shouldn’t be in here. He’s not allowed. Steven will get in trouble if he goes inside the room — more trouble than he will be in from just opening the door. And he does not want to be in trouble. He does not want the back of a cold palm. Bad Boys are those who get in trouble, and Steven is not a Bad Boy. His mother said that he was Good, so why does he do this?

He wants the warmth of fingers pressed into his scalp, uncurled appendages holding him close. He does not want what he will receive. But it has been decided. And he cannot change.

It beats again, reminds him that he, too, is alive.

It hurts).

The carpet does not feel any different from the hallway. Not softer, not cleaner, not warmer. The room itself is not alive in the same way that he is, in the same way that he will always be. It does not hold power over him. It is just a room. A dusty room that used to house terrible people that he will never have to see again. It is just a room that holds a dressing table, and a nail file.

It’s placed in the middle of the vanity set, placed delicately next to colours of reds and whites. Lipsticks still capped, gifted jewellery untouched, perfectly wrapped with small names printed on the edges. He wonders if she ever wanted any of it, if she was ever allowed to open her gifts. She would be forty-two, now. What presents would she have gotten if she stayed? Would she have been able to see them? To feel the pleasure of wrapping paper unwrapped from the seams? Or would it stay like this — a mass of unfeeling, unthinking gifts to be left to rot?

Steve takes what is now his, sees the way that the dust has left its mark.

The door stays closed, then. He leaves as quickly as he can, dust settling over the memories, again, and stamps his way back to the bathroom. Steve hauls in a barstool that has never been used, holds the tool up to his head, looks in the mirror, turns and turns until he can see the bone wood in all its horrible glory. It is too visible, and he does not like pain, but it needs to be done.

The nail file does the trick. He saws at it for hours, watches as the light disappears from the window, turns on the light, yellow cast his skin in sickness. Back and forth and back and forth he shaves down what is him, until his hair falls back into place, until the bone-dust has covered the tip of his nose and the rim of the sink.

Steve turns on the tap, washes it away, and it is gone.

— — —

The news comes faster, this time.

Steve isn’t surprised. He’d be a little bit more surprised, a little bit more worried about the police, if they hadn’t found Neil Hargrove’s body. It wasn’t as if he had just killed him in the woods, no, that man, for all his secrets and his parading and his lies, he deserved to be put on display. What was left of his flesh and bone, when it had been oh so conveniently placed on the place’s doorstep, was meant to be found. Monsters deserved to be culled, Steve thought bitterly, even if he is the one who has to do it.

“Sources say that the body of Neil Hargrove was found strung up to a lamp post outside of the Hawkins Police Department, with his chest split open.”

Steve watches as the woman on the TV screen is ushered away from the area, away from where Steve had been last night, by a police officer. There’s a glimpse of Hargrove’s body in the background, being lowered from the streetlamp. From this angle, with this quality, it’s hard to tell what’s really going on. But, even underneath the moon, he knows what he did, what it looked like. He can make out the outlines of Hargrove’s hands, tied up with offal, strung like man in sin. He sees the loll of the man’s head, mouth open wider and wider in unhearing shout, and wimpish scream. Ribs pulled forward and out like a flowerbed in bloom. Steve wants to ask if he’s ever been this pretty.

He hears the man shout something, off screen, watches the swing of the cameraman’s body back behind the tape.

“You’re not allowed to be here!” A man shouts. “You’re not allowed to go past this tape, or say those things until we—”

“Do you think that there’s a pattern?” The woman barrels on. “Do you think that whatever killed this man was the same thing that killed Tom Holloway in the woods—”

Steve turns off the TV. He doesn’t need to know anymore. He knows the details so vividly, already.

— — —

(What is surprising, is the letter. Or, note. Letter is too formal, and this is only a few words in garish handwriting that he can barley make out. At least it’s recognisable. There is no name signed, and there does not need to be. Steve can smell the scent of him on it, and even without that, the handwriting is a dead giveaway.

Meet me at our spot.

Steve knows that he probably shouldn’t. Should probably run in the opposite direction, and yet he still goes. There’s something compelling about Eddie, something in the way that he talks, in the look in his eye that leaves Steve wanting more. More of what, is the question — one with many more answers than Steve is willing to admit).

“You did it.” He says. “Again. Even though you said that you didn’t want to, that first time, that you didn’t mean to.”

It’s not that simple, though. Because Steve knows that there are reasons behind his actions — reasons that stem further than that of petty pleasure or personal gain. He is not who he once was, who he has been coasting as. It doesn’t stop the warping of Eddie’s face, the snarl that he holds, upticked lips curled around the next word that he so desperately tries to grasp at, and, failing words, he just stares. It doesn’t make him feel good, no. But what part of any of this has been good?

Steve can’t bare it. He can’t keep looking at Eddie the way that he wants to, that he thinks of to himself, and see the way he looks back. He knows that it is his fault, something to do with who he is, and what he is, and what is fundamentally part oh itself, what has formed and forged who he is— shaping into something wonderful and disgusting to his own heart.

“He deserved it.” Steve says. Because how is he supposed to make Eddie understand any of it? He can see the way that Eddie’s lips curl, and the change in his demeanour; no longer angry at him, now just… exhausted. Steve tries to find the words to say what he truly means before Eddie can comment, because that minute sigh, exhalation in disappointment, is too much to hear. “Nothing would have happened if I left him. If that man were still alive he would inflict more hurt than he would be he dead.”

“That doesn’t mean that you get to decide that!”

“And what would you have me do?” Steve asks. “Leave him to live? Leave him to destroy more lives than just his? Is he worth so much more than those he hurts?”

“You don’t get to be judge, jury and executioner— there are fucking laws—”

“Oh!” Steve laughs, prickly back against the wall. “Eddie Munson talking to me about the law—”

“Tell me you won’t do it again.”

“I—” He stops himself. He can’t keep that promise. He doesn’t know if he wants to. Eddie crosses his arms over his front, eyebrows drawn in something that Steve can’t name. He wants to know what to call it — what to call him — in this moment. Hair unkempt, eyes glassy, stained. Like a prophet, or warning, outlined in thick oil. There’s a pit in his stomach that opens into a thin ravine, losing bits and pieces of himself to his body.

He does not want to hurt anyone. He never does, at the beginning. People are too soft— flesh and bone too easy to press fingers into. Sometimes he isn’t aware of what he does, the way that the things he does effects people. He has never wanted to hurt anyone, but aren’t there some people that deserve it? The people who slip through the cracks, the one that inflict hurt on others in ways that should not be spoken of, that are hushed away and swept under carpets and closed behind neighbourhoods of two-to-three story houses with the woods bracketing their secrets. Don’t they deserve it?

Steve smiles.

“You’re in over your head, Munson.”

“Well it’s my head on the fucking line, Harrington.” Eddie spits the name to the ground, to Steve’s chest. He does not flinch. It does not hurt. “My god, it’s like you never fucking learn. Do you even remember anything from when we last did this? Satanic killings, rumours, blame — any of that ring a bell in your empty fucking skull?”

Eddie pushes off from against the wall, crowds Steve to his. He presses a finger into Steve’s chest, teeth bared as he speaks.

“It’s like you’re trying to blame it on me. If a violent murder in the middle of the woods wasn’t ritualistic enough, you just has to, what, string him up like some holy sacrifice? Did you stop to think of who they’re going to question, or point fingers at, huh?”

No. He didn’t. He just wanted to help Max. He just wanted to help Billy. Neil had to die. He was hurting them. He had to leave.

“They won’t question you.”

“And how do you know?”

Pin it on someone. You can do it. You’ve been doing so well. Won’t it be so easy? It would be so easy.

(Steve doesn’t want to blame anyone. Nobody will be blamed. Nothing bad will happen. Maybe time will implode and everything will revert and he will only be left knowing what once was, and he will be able to fix these things, and he will feel what he is meant to feel. He fill go back to being boring and playing his part. The dolls will be put to sleep, and their houses tucked back into the basement to collect dust and lose memories.

He will go back to playing his part. Smile and kiss and drink and fuck. Fail his tests. Wear ugly collared shirts that his father bought him. Wear the sneakers that his mother likes. Pretend to like smoking by the pool and tucking cigarettes behind his ears. Chug beer till he passes out. Drive. Never cry — because crying is an emotion, and men do not show emotion. Shout. Get angry.

(“Aren’t they emotions, too?”

“No. Not for us.” He says, the memory of him repeating behind fogged glass and blurry eyes. “Do you understand?”

“Yes.”

“‘Yes’ what?”

“Yes, sir.”).

He will become who they want him to be, and they will like it. And they will like him.

It will not be like this— not quite popular, not quite an outcast. An anomaly of a being that does not fit in where he is meant to fit in. Basketball player unfamiliar with team jokes. Classmate unwilling to participate. Neighbour that never introduces themselves. Boyfriend who can and can’t understand his girlfriend. Child who lives alone. Bad friend. Bad babysitter. Jobless. Floating. Unwilling. Willing. Taken. Hurt. Inflicting. Inflicted).

“I don’t.” Steve answers, quiet and unsure. “I don’t.”

Eddie nods, eyes justified. He leans his forehead against the brick wall next to Steve, shoulder brushing up against his shoulder. The shirt that he’s wearing clings to his back delicately, brushing up against the knobs of his spine. It’s weird to see Eddie without his jacket, without his vest, but it makes it easier to so the way he moves— the way he shifts out of the corner of his eye. Steve can see the way that he breathes, each intake of air exaggerated by his thin shirt.

A curtain has been made between them out of Eddie’s hair, and Steve turns to get a better look. The curls are uneven, no two the same. Thickly coiled hair shifts apart for a second to see his face, his eyes.

Oh.

“Are you—?”

“Just— gimme a second.” Eddie breathes. “Please.”

Steve nods, shifts back so that their shoulders touch. He lets his hands sit by his side, unsure of what to do with them, with what he’s allowed to do in this situation. Eddie is quiet. The only indication given that something is wrong is the laboured way his chest moves, exaggerated and emulating breathing slowly, and the droplets sinking into the soft sand and dirt beneath them.

“Did you—” Eddie sucks in a breath, wets his lips. “Did you talk to them?”

He doesn’t mean the police.

“I tried.”

“Not hard enough, I guess.” Eddie laughs, thunks his head against the brick wall. He’s quiet for only a beat too long that has Steve questioning if this is what does it— a petty conversation and not the revelation that he is not wholly human or himself, before— “There isn’t anything you can do to make them stop?”

“Eddie, you know how Hagan and Carver are—”

“Dicks?”

“Yeah,” Steve huffs. “Real fucking assholes. There’s some weird pissing contest going on between Billy and Jason right now— something to do with who’s gonna be team captain after I graduate.”

“I don’t think either of them are particularly good options,” says Eddie. “Too headstrong. Plus, they’re both—”

He spins around so that his back is now facing the wall, head directed towards Steve. There’s a shimmer in his eyes that wasn’t there before, as if something inside of him has been mended.

“Dicks?”

“Yeah.” Eddie says, smiles up at him. Then, smaller, he mutters something that Steve thinks he shouldn’t have heard, a thank you for trying that gets lost as they go their seperate ways to first period.

— — —

He doesn’t move. He knows that if he moves then they’ll look at him under the microscope again, draw more blood and squirm and test as he sits, strapped to the large folding table-chair. It’s like the ones that the mum’s used to put outside the school for bake-sales when he was younger (not as if he’s old, no, just… different. He can’t remember the last time he lost a tooth. The natural way, at least). So he doesn’t move, because he knows what is best for him — how to survive. It doesn’t stop it from hurting any less, though. The way that the people and their clinical stares stop and watch behind glass that they think he can’t see through: their demeanours are thick with anticipation and something that he would call lust if he knew what that word truly meant. Not in the way that he will learn it to mean, in the way that he will move and shift against others and kill it the l-word that isn’t the l-word that they want to hear, but, instead, something primal.

It is almost the same here. There is nothing comforting about the lust that they display, though. It is like they don’t even know it is there, as if they hide behind the medical masks and white rubber gloves covered in something sticky, behind pressed white shirts that crinkle at every movement. He is oh-so aware of how they move; every move they take, every breath they don’t.

It hurts. And there is no other way to put it. Not like getting a scraped knee, or sliding down the stairs in what he thought would be like sledding, or like a rough palm and warm rings, no. This is pain. This is what he had read about in the before, in the picture books that he could grapple onto before they were ripped from him, from the soft words of the teacher as she asked if he was alright. It’s not fair, and he knows this, deep down, he knows that it isn’t, but there is a part of him that wants to ask why. Why are they doing this? Is it because he had been too loud and too quiet and too hyper and too tired? Was he too much? Not enough?

No.

He knows why. But he latches onto excuses like rotten meat and stinking flies, like he is a decaying body and not here. Steven knows the reason. It is the same reason that leads them to do their little ‘medical tests’ for the sake of science, don’t you want to help humanity? and when that didn’t work, they asked don’t you want to help your country? They posed it — the thing within his blood that they so desperately try to taste — like they were doing good. Like they weren’t the bad guys in their black suits and guns and muscle just because they wore white shirts. Steven doesn’t know much about the world — not enough to know how to make a cocktail, or how to do long division, but he has read enough comics about Superman to know that this is not good.

They wait on the other side of the mirror, and Steven watches himself; the grooves of his hands turned in a way that they shouldn’t be. Like he is Stretch Armstrong, bent and re-shaped to be something that is not real.

They broke his hands.

That’s all there is to it.

There shouldn’t be any more to it.

They came in, and strapped him down, and the man with the white hair — old and ugly and too much like my father, Santa-coded horror — had shushed him with a kind smile and said that he knew Steven was capable of fixing things, you don’t want to hurt anymore, do you?

He tried not to scream as they did it. His father always said that showing emotions was a sign of weakness.

When he had, unintentionally, fixed them, his hands, because he had waited long enough, he thought, that they had all left and gone to sleep, because he had counted the painstaking seconds and mimicked a clock in his brain, trying to make a game out of it. How long can he go without blinking? His high score was three minutes and fifty-five seconds. He could see it now: flashing on the screen of the arcade that he had been in (once), before being dragged out and lectured about how to be a man.

He missed the arcade. Steven often wondered what new games they came up with while he was away. If, when he returned, his friends would welcome him with open arms, and ask about how his holiday in Europe was. He’d lie, of course. I saw the Eiffel Tower and drank a sip of red wine from my mum’s glass as she ate snails! And they’d all say ewww! because of the mention of the shelled-slug, and go looking for them in the garden, and then they’d forget about how Steven didn’t smile as much, how his arm looked like the man who lurked around the gas station that they bought cheap snacks from. He’d cover it with his mum’s makeup, he’d reckon. And they’d never know.

Don’t you see? Steven asked. They’ll all go away if we just wait. Everything will go back to normal.

He just needed to hold out until he was well enough, until they thought that he was nothing special. Steven just needed to be good enough to keep his arms limp in the chair, and hush the loud voice asking him, begging him to let it fix the hurt.

And we can be home again? It asks back. Small and quiet like it never has been before.

And so they wait. His hands lay limp at the wrists, because he knows that if he wiggles his fingers, they’ll move too much and start to rearrange in the way that they are supposed to bend. Not this deer-legged thing that he calls his wrists, but something more human.

Of course. Steven answers.

(It fixes itself. Not in the voice-inhuman way, but in the way that bodies do: with time. Bone fuses in a way that it isn’t supposed to, and Steven isn’t even worried about the pain anymore — how is he going to hide this from his friends? They’re not going to want to talk to someone whose hands look like his. This isn’t something that his mother’s makeup can conceal.

And so, they re-break it. The people with the gloves and the pressed shirts don’t appear this time. Instead, as he closes his eyes, he looks past the mirror and he sees a small head and a sloped nose, and he feels it in his wrists, slowly, shifting it back to how it once was.

It is then that he decides he doesn’t want to forget.

Because he knows, then, that there are others, with hands like his, with dreams like his).

— — —

He doesn’t want to be here, but he needs to keep appearances up. The basketball team has been positively up Steve’s ass recently— no, not about the murders (plural, now, which is wrong and horrible, and should have been stopped so soon, so quickly, but that one was needed), but about how many practices he’s skipped. As the pseudo-captain, they look to him for guidance, like little lost sheep, put it seems like they’re growing into themselves now: angry and hardheaded, stubborn and red.

The curfew hasn’t been lifted yet, and everyone here will leave before it is 11:30, time enough for them to be inside their houses, inside their rooms, by the time it strikes 12. Steve thinks that the curfew is a little useless, not because of why or who it was put in place for (he’s disregarding the fact that it is him that they are being protected from), but because people are normally dawdling their way home by 1. These parties (if you can even call them that) are just little get togethers that usually take place the day before important things. The night before the 4th of July, graduation, Christmas, exams. People in Hawkins, for being so fucking boring, have no idea how to plan around the minimal celebrations that happen, here.

It doesn’t help that, the place that everything takes place this time, looks so similar to that of the bathroom he and Nancy spoke in. It’s probably due to the fact that all of Hawkins is so single-minded in loving conformity that any and every house within the same tax bracket looks the same, but that is entirely besides the point. Steve can picture it all: shouting here, spilling the cup there, Jonathan racing through the room, heartbreak, heartache, nothing nothing, and, then, beginning.

So, he doesn’t want to be here, but he has to, because that is what normal people do, and that is what people who are on the basketball team do, because playing sport is all about the alcohol and the sex and looking away as people swap spit in the corner.

They’re a weird pair. That’s all he has in his mind as he watches Chrissy Cunningham and Eddie talk to each other, hushed as can be through the music. It’s hard trying to isolate their voices, and Steve is this close to asking someone to turn down the god-awful pop that he usually loves, grating on his brain. He needs to be able to hear them. He doesn’t know why — call it a gut feeling, a feeling of the voice.

Steve shuffles closer. As close as he feels he can get before his heart starts beating so fast that he has to recall the symptoms of a heart attack.

“…are you…”

It’s Eddie’s voice — bracketed by the booming music, but unmistakably his. Steve tries to read his lips, the way they move and push and bite, tries to sound them out with his own mouth, pictures what they might say. He can’t do it, really. He can try and fill in the blanks as best he can, but his mind is auto-supplying what the sentences could end in. Are you okay? Are you going to leave soon? Are you sure?

“Of course… he would never…”

He? There are too many people it could be. Steve tries to narrow it down, and it is surprisingly easy. Chrissy and Eddie are too weird of a pair to be able to communicate with each other so plainly if not for their linking ‘he’. To Steve’s knowledge, Chrissy would never take drugs. She’s like Nancy— generally pretty straight-laced, not wanting to ruin anything that isn’t already. So, it’s unlikely that Chrissy would be buying (and, Steve considers, if Chrissy did want to buy from Eddie, she probably wouldn’t do it out in the open, like this), so they have to be linked with who they know.

Steve almost throws his own name in the mix when he spots Jason cheering, beer almost slipping from his fingers as he raises his arms in cheer at— something. Steve isn’t interested. For someone who took Chrissy here — and he knows that he did, because, again, when has Chrissy Cunningham ever attended a Hawkins party like this? — he seems to be quick to ditch her. Especially when she looks, well. Concerned. Like she’s about to cry. Or throw up. Or both.

He’ll check in on her, later. Once this party is nothing but a stupid night to look back on, like every other stupid night.

“…if you’re sure…”

“I’m not… he’s always been like…”

Steve shifts closer, leans back against the countertop to try and make their voices clearer. He closes his eyes, tries to focus in on—

“Harrington!”

“Hargrove.” Steve acknowledges, opens his eyes enough to see his smarmy face.

“Enjoying the party?” He says something, but Steve tries to focus on both conversations, mind swimming.

“…find some way to help…”

“…been so long since you’ve shown your face, pretty boy…”

“…there’s nothing for you to do…”

“…been an asshole recently…”

“…are you sure? I can…”

“So, what do you think?” Hargrove says, closer, this time.

He doesn’t know what he asked. Steve doesn’t care. What matters is that he can hear the slight conversation of Eddie and Chrissy behind him, something that he needs to be able to hear, to be able to know and to make sure they’re okay, and Billy fucking Hargrove is standing in his way.

Tell him.

No! That’s not going to be productive, and will absolutely end in Steve getting his head slammed to the counter. He very much likes having his head attached to his body, thank you very much.

“Sounds interesting.” Steve answers. Passive. Safe.

Billy huffs. “‘Course you would say something like that. You weren’t even listening were you? I saw the way you just… stared off into the distance.”

Billy eyes him for a second. Steve doesn’t know how to answer that. How is he supposed to say I think something bad is going to happen tonight, and it is absolutely going to be my fault. And, also, I killed your father, even though I don’t like you, because nobody should have to live like that.

He doesn’t know how to answer, so he doesn’t. And Billy leaves. And Steve hears the words hurt me and I know someone who can help and nothing will change and then he gets the confirmation he needs— Jason’s name in high definition, past the music and the beer and the smell of sweat, and he closes his eyes, and he goes out the door, and everything is exactly the same as what once was.

— — —

Steve knows that he killed Jason.

He’s losing control.

He doesn’t even have the state of mind to bring himself back home. Because, when his body shifts back, when the feels bones folding in one themselves, fusing together like a sickly child who fell down a tree, he is met with the cold of the woods, the remains of Jason Carver, and a girl’s broken body, eyes unseeing, in the middle of the clearing.

Steve scrambles back— into Jason. He looks to his palms and the colour that they shouldn’t be. Oh god. It doesn’t get easier. Why? What happened? How did he get here? Why is there— who is— he doesn’t look anymore. Can’t make out the colour of her hair from the blood staining it. He doesn’t want to look any closer. He can’t.

He wipes his hands across his pants, tries not to let the metallic smell reach his brain, but when he has to side-step the girl and her almost-sleeping form, he almost vomits. Feels the saliva pile in the back of his throat, the feeling of his throat contracting. He presses hands towards his mouth, the smell too close too close too close, and swallows.

Steve just needs to get home.

— — —

There isn’t a school that he can hide in, this time. To wait and to bide his time, and to look at Eddie from a distance, feel his eyes on the back of his head— no. Eddie confronts him properly, this time, comes straight into his home, where Steve has been sitting since the confirmation that a Hawkins High student had been the latest victim of the serial killings. It is nothing, and exactly, like the first time it happened. The uncertainty is gone. He cannot just scare him, will him to leave him alone, and then pretend that nothing had happened when they enter school ground. No. Everything has changed, more than it had before, like nothing at all.

“What the fuck do you think you’re doing?” Eddie asks (shouts. He shouts it so loud that Steve thinks that the windows might break, that the neighbours might hear. It rings in his ears like a godforsaken choir, humming beneath his eyelids in static glee). “And don’t give me that oh I didn’t know what I was doing-schtick, Steve. It sure as hell didn’t work last time, and it’s not gonna work here.”

“I know.”

“I mean—” Eddie paces around the kitchen. There are no broken vase pieces, and yet he still side-steps around the carpet and the shame that Steve exudes into the house. “A kid. That’s what he was. Like, Jesus fucking Christ, Steve. Yeah, you had ‘reasons’,” and he twitches his fingers just so to be mocking, “for the last few ones, but, shit!”

Eddie paces a few more steps before using his hands to really show him what he means— waving and wild in a way that makes Steve think, if he were anyone else, hie might throw something.

“He was fucking seventeen, Steve. Seventeen. He didn’t even get to live long enough to graduate, or drink, or do any of the horrible wonderful stupid things that adults are allowed to do. Fuck—”

He sits down, then. And Steve watches. He doesn’t know how to comfort him. Because there is a part of him that knows what he did, is something that he shouldn’t. That he should have a code, a set of rules that said not to hurt those who have the possibility to change — but wouldn’t that stop him from inciting justice? Doesn’t everyone, theoretically, have the possibility for change? What makes a man a monster and a monster a man? Steve knows that he is both, and yet he does not have an answer.

There are those that do the monstrous things that would be considered immoral and hurtful, but when punishment is enacted upon them, people scream out and cry. Why are they afraid of it? Surely they must know that the unworthy must be punished? Nothing should stand in the way of justice. And so what if that justice has to be him? He will do what needs to be done.

Good. This is right.

If it were someone else, Steve knows that he would be dead. He wasn’t the best when he was Jason’s age, and if the thing in the woods was someone else, who acted exactly like him, he would no longer exist.

(Maybe that’s a good thing. Maybe then none of this would have happened. Or maybe it would all happen exaclty the same, and Steve Harrington would no longer be able to breathe, just like Jason Carver no longer walks).

“—Steve.” Eddie takes a deep breath before approaching Steve like he did in the woods. Timid and afraid, like he was then, his footsteps are steely and planted deep. “You know that this is wrong, right?”

“I didn’t want to—” That doesn’t answer the question. It does not matter what Steve does or does not want. “Yes.”

Eddie lets out a breath, slow through his nostrils, flaring in something that Steve hopes is not distaste. “So you know that there needs to be an end to this.”

Steve tilts his head, tries to pick him apart at the seams. Of course there will be an end to this. Steve is not immortal. He will not live forever. He will not do this forever. There are just, sometimes, people who do not deserve to do what they want, at any given moment. He tries not to take offence at the way that Eddie speaks downs to him — like he is a child that has swiped icing off his mother’s birthday cake.

“Yes.”

Eddie backs away. Runs a finger through his curls. Steve wonders what they might feel like. He knows what it smells like: cheap shampoo and no conditioner (something that he endeavours to change), hints of smoke and nervousness. No fear, though. Which always makes him feel a little better about what he’s doing. See? Not everyone’s afraid of him. That must mean that what he’s doing is not wholly and fully ‘bad’.

“My offer still stands. I can— if you let me help you,” Eddie says as he wets his lips, “we can figure this out. I can help you figure this out, and control this.”

(It doesn’t sound like a bad offer.

But why would you want to do anything different? Nothing bad has come of your actions.

Yet. Nothing bad has come of his actions, yet. But why would Eddie even want to help him? He hasn’t been the nicest person to him— and the last few times that Eddie had even suggested helping — the woods, the meetups, the house — Steve had scared him away with threats and teeth and blood. There is no reason for help to be given.

He does not deserve it).

“Why?” Steve says, finally. “Why would you want to help me? There’s nothing in this for you— and how would that even work? There are moments that I don’t remember, when I feel like it isn’t truly me that is there, that it is me but not, but different, like I’m floating above myself, aware and not, of everything that’s going on.”

“I could—”

“You saw it— me— on that first night.” The horns, the not-vision, unmoving teeth and shifting veins, “is that really something that you want to work with?” Am I really worth it? Steve says, but he does not, because Steven is not allowed to say things out of turn.

“Yes.” Eddie repeats back at him, paces forward in an aborted movement to move his hands somewhere close— to his face? To his shoulder? Steve does not know, but he finds himself yearning for the touch that almost-was— and awkwardly rests them on an invisible cabinet bracketing Steve’s face. “You asked for my help that time in the woods. It doesn’t matter how— we’ll figure it out, okay? Because you— you’re distraught—”

“I’m not—”

“—I can hear it in your voice and how it shakes and, fuck, Steve. When you were there, when you weren’t you, you tried so goddamn hard to tell me what was going on. So don’t sit there and tell me that you’re not allowed to change, not allowed to be helped, because you need it, and that should be enough.”

He smells like… warmth. Something that Steve wishes could be closer. He does not know why it feels like all time has stopped, or why his heart is beating faster than it should, or why his neck is too-red-hot, or why he can feel each individual spine of his hair sticking into his scalp like a porcelain doll, or why he feels as if there is an open, flowing, river that cascades down his cheeks and into the ridges of his nose, the swell of his chin.

“I can help you. You just have to let me.” Eddie rests his hands down, warm and cold through the fabric of Steve’s sweater. His thumb rubs circles into his collar bones, and Steve wonders why his eyebrows have drawn, and the air tastes like salt.

“I don’t know—” Steve clears his throat, because no Man is allowed to look unbecoming (Why? Why aren’t I allowed to— no, sir. I’m not—). “I don’t know what to do.”

“We can work our way backwards. Start from the freshest one, okay?” Eddie sits down on the chair next to Steve, turns so that he faces him. “You said that you didn’t want to… kill him, right?”

“No!” Steve lets himself sit back, relax. “No. I didn’t like Jason, but he was never— he was an asshole, but isn’t everyone? I didn’t go after him because I didn’t like him. It’s like— every time there’s something there — I saw what Hargrove had to go through at home with his dad, I saw the way that Holloway treated everyone around him — it’s always something.”

“Then what was Jason’s? What was his reason?”

“I don’t know— I’m sorry. I remember the party, and how Jason was pushing her, but it was just— I think it was just— stereotypical teenage relationship shit. Nothing special. I think. Sometimes it’ll come back to me a bit later, but I just can’t— I really didn’t mean to. I knew that I set out to do what I did to Hargrove’s dad. But Jason? I didn’t want to. Not consciously.”

Eddie sighs. “You don’t think this is like a, what’s it called?”

“Split personality? No. That’s not what’s happening here. It’s like— a passenger that’s tagging along. Sometimes it tells me things, lets me know when I’m doing something right, but it’s not like that.”

“So maybe like a possession or something?”

“I don’t know. It sounds more right, but I don’t know much about possessions. I feel like you’re more of the expert there.” Steve laughs wetly, allows himself to wipe at his cheeks.

“Yeah,” Eddie smiles. “Maybe.”

Steve tries, then, to remember. What did he do? Where did he go?

He remembers some things: the party and the sweat. He knows that he came to the party wanting to do something, to get away, to pretend, again, for a moment. Steve knows this. This is true. Things get a little foggy after that. He imagines that he met up with— no one. Because he’s not necessarily friendly with anyone outside of his small, non-partying, circle, and there’s now ay he would have approached the basketball club of his own accord.

He went to the party. He does not know if he enjoyed it.

(He does not think he did).

“I don’t think I can.”

Steve knows that at one point, with his arms resting against the table, he overheard murmurs. Words and phrases that tickled the back of his brain — things that he had heard of before, but had never heard said. Things that should not be said aloud, should be left to be thought and pushed away once realised.

“Let’s just try again, okay? Who do you remember. That might be easier than trying to figure it all out at once.”

Jason.

Chrissy.

Eddie.

He saw them. All of them. He knows this.

They don’t belong together. Steve remembers the words flowing round his head. They don’t belong together.

Eddie and Chrissy and Jason.

“…it becomes foggy after that. I just remember you and them.”

“Right, yeah, I remember Chrissy saying something about Jason and how he was— were you drinking?”

“Sober.” Steve answers.

Eddie paces back, “Maybe it has something to do with emotion? I know that Chrissy wasn’t… having a great time, to say the least. And Jason wasn’t really helping with any of that. Maybe you overheard the things that he was saying — because, trust me, they weren’t good words — and got mad, and, unintentionally, decided that he needed to ‘leave’?”

That sounds right. That feels right.

“I know that I was close to wanting to throttle him, myself. Which it— I probably shouldn’t say considering that he’s, ya know, dead.” Eddie huffs, awkward and gangly in a way that Steve wants to feel.

Jason is dead. Steve killed him. Maybe the help that Eddie is offering— the one that Steve so desperately needs, is one that he should accept.

They don’t mutter much after that — small things that are lost to the awkwardness of their now not-so-friendship-not-so-enemy relationship. Eddie steps back when the streetlights turn on automatically, glaring in the face of his windows, into his eyes. He mutters something that sounds like I should get home, and Steve agrees and mutters something about curfew, and Eddie steps away, like he was the Earth and Steve the Sun, pulling him closer and closer in such a proximity that makes Steve want to taste the air, and then Eddie is wiping his hands on his jeans, and Steve is walking him to the door, and they say goodbye at the same time, stopping because they are just out of sync, thinking the other has more to say — a pause, as if written on a stage-play — before Eddie is twirling his keys around his fingers, and Steve is saying get home safe as if he is not the only monster in Hawkins, shutting the door between them and staring and staring, because what he really wanted to say, under no influence of nervousness or distress of that voice that he is somehow complying with, was do you want to stay the night?

— — —

“How have you been?” Jonathan asks.

It’s something that Steve feels like he’s sick of hearing, of asking, of answering. He doesn’t think that anyone actually likes being asked how they’ve been, especially if they’ve actually been real shit. How are they supposed to respond, then? Actually, yeah, my whole life has been turned upside down in the last couple of months, I feel like I can taste your thoughts, and I think I might have a crush on a man. Steve doesn’t know which one Jonathan would be more surprised by. Probably the last point.

“Not bad, not bad. You?”

“Good, yeah. Nance and I have—” Jonathan scratches the back of his head, as if to realise himself, who he is talking to. “We’ve been… good. Yeah.”

Steve sighs. Of course. “You don’t have to, like, hold back on me, man. It’s just— weird not being able to talk to everyone like we’re still friends. I mean— we are, right? Still friends?”

(He has to ask. Because he still feels like there’s something that’s dividing them. Like there is a wall between them despite both of them trying — because this time, Steve is, this time he really truly wants to try — there is still something dividing them. Like the woods and the class and the money. Like the flesh that bore them and the blood that loves them. Too different, too similar, not enough of either to fix them together neatly).

“Yeah!” He answers. “Of course, it’s just—”

“Still weird?”

“Yeah, but also, I haven’t really seen much of Nancy or Barb, recently. I thought maybe they were avoiding me, or something.”

Steve thinks back to the last time he saw either of them. It wasn’t that long ago and nothing was… weird. They were acting like they usually would, talking about how they were going to have a little girls night sometime.

Maybe they were just very secretive in their planning. They always have been whenever they wanted to do something big — surprise birthday parties were their forte and, ever since the one time that they accidentally let Steve know and he accidentally ruined it, they’ve been pretty close about what they plan. Closed books.

“Maybe they’re just doing their girls night? They were planning one, recently.”

“Yeah, I’m probably just paranoid about it. I guess it’s just weird not spending a weekend together. It’s freaking me out a little, not seeing everyone together. Especially with everything that’s happening.”

Steve clears his throat. “Yeah. Freaky stuff, man.”

“I just can’t believe that nothing’s being done about it. Like, you’d think that they would be trying to catch this guy, right?”

Yeah, right.

Lights pull up beside them, and Steve stops himself from answering.

“Chief.”

“Hopper.”

“Jonathan, Steve.” He acknowledges.

If Steve could never see the Chief again he’d be all too glad. What Jonathan had said before feels too close for comfort— the police should be looking for him. Was there some way that this could be linked back to him? Well, of course Eddie still exists in all his glory, and Steve keeps telling him things but— he trusts him. Which is honestly the weirdest feeling because Eddie could just… break that trust. He could do whatever the hell he wanted. He has no obligation to Steve.

No— this is. They’re friends. No matter what anyone says. Maybe-friends. Almost-friends. It doesn’t matter that Steve feels like he wants more.

“The kids late again?”

Jonathan sighs, “Yeah, you know how they are. You say one time and they push it by half an hour.”

“I don’t even know what they do in there for that extra half-hour,” Steve sighs. “It’s the movies. Not the arcade.”

Hopper huffs air out of his nose in a semblance of a chuckle. “It’s no harm done. At least we know they’ll get home safe.”

The kids bundle out the movie theatre, almost-empty container of popcorn being pulled this way and that as they race towards the awkward pickup trio.

“I thought we agreed on 10?”

“Yeah, well, we thought we agreed on 10:30. Right guys?”

Steve turns to look at the rest of the party, all nodding their little heads as if he can’t tell that they’re lying. Beside him, Jonathan sighs and nudges Steve in the shoulder are if to so what can you do? He relents. Drops his hands from where they were crossed across his chest, lets his shoulders relax. Hopper has his hands against his hips, in a proper Dad Stance as he watches Jane with the rest of the group.

Steve doesn’t know why he’s so anal about sticking to the times — the times that were only put in place because of Steve existing in the first place — but maybe it just has to do with how he wants to please. Steve mirrors Hopper, tries to see what he does, in this little group. He’d always wondered what it would be like to have children. Would he love them like this? Would he care for them like this? He thinks he’d like that.

Dustin says something that Steve can’t make out, that has Jane swatting at his cap. Steve tries to focus on the words they say, on his own beating heart, but all he can think about is what could have been marker against her wrist.

Do they know? Do any of them know?

Steve tracks Jane with his eyes, tries to place her, tries to imagine her in that place. What was she like? Was she always there? Did they know each other? Hopper places a hand on her head and ruffles her short, curly hair. Did he know?

It’s her. She’s the one.

She can’t be. That wouldn’t make— it would make sense. He just doesn’t want it to be. He doesn’t want it to be real. He doesn’t want to image what that would mean if what he saw wasn’t just some fucking mistake.

Time resumes. He pulls out from the driveway. Steve doesn’t mention it. He pretends that he isn’t wide-eyed as he looks back to his car, as Hopper and the girl whose-name-probably-isn’t-Jane drive away.

“Get in the car, shitheads. We gotta go double-time to get you home.”

There’s a picture in his mind; this is how it will play out: Steve will drop all the kids home, with Jonathan taking Will and Mike, and Hopper taking not-Jane, and Steve taking the rest, and when he goes to drop off the last kid, he won’t be talked down to by the parents. No, instead, they’ll just give him a tight smile, one that he thinks says do better next time and he’ll give them a goodnight and they’ll shut the door, and he will do better next time, and he’ll just blame it all on what he thinks he saw.

At least, he’ll try. He doesn’t think that he’s allowed to keep promises, right now.

The kids pile in. They chatter on— some argument or another that Steve pretends to have a stake in. Why, yes, he does think the Star Wars movie with the little cute dudes is the best one. No, he doesn’t think that Superman is the best superhero. He lets the car sit for a moment, warm up just a bit, enough so that he waves to Jonathan as he pulls out of the carpark with Will, and into the road.

Secretly, he checks in on Max. How she huddles in the backseat between El and Lucas, crowded by their bodies. He hopes that she’s okay. Steve should know— that feeling of I shouldn’t mourn for this person, they were horrible in all the ways that matter fighting with but I knew them, but things have changed now aren’t easy things to deal with. No matter what age it happens, now matter how much time passes, it will always be hard.

It’s only been a few weeks since Steve killed her step-father. Neil. Only a few days since Jason. He wonders how many people will miss him. Probably a lot, if Steve had to guess. There’s a part of him that feels like he should miss Jason. He was the one to see him in his last moments, even if he can’t remember it. But every time Steve thinks of his face, of his words, they just jumble together into a gag-reel of his worst moments.

“You are so wrong!”

“How am I wrong? Supergirl would one-hundred-percent beat Wonder Woman. No competition.” Lucas says. Steve hears in his tone how he doesn’t believe it himself — or, at least, he doesn’t really care. Is just saying things for the sake of saying things. He doesn’t want the night to end. He doesn’t want to leave Max.

“Okay, yeah, Supergirl has all her flashy little powers, but she’s just some dude. Wonder Woman is Wonder Woman! Like, c’mon!” Her voice is so exasperated that she’s started to gesture and roll her eyes.

The continue like that until they reach the first house.

Lucas gets dropped off first, wide smiles and too-loud goodbyes for this time of night, Steve watches as he makes it to his front door, as he’s welcomed in by warm hands.

The kids continue the conversation, away from Supergirl vs. Wonder Woman, and towards other menial things. Do you think Mike will be on-time to first period tomorrow? Doubt it. I think I can convince Will to trade some of that homemade cake for some of my nougat. Nobody likes that but you, Dustin. We should make more friendship bracelets, have some for every season. I’d like that. And then they hug and Dustin runs up to his front door, cat meowing so loudly that even Max can hear it from down the driveway and in the car, until he is inside.

“How’re you holding up?” Steve asks, as if nobody has asked her before today.

She huffs out air from her mouth, head lolling against the back seat. “Can we just… not?”

Steve winces. “Yeah, okay. That’s fair.”

They pause — Steve watches her from the front seat, feeling all too like a Parisian taxi driver in the middle of the night chauffeuring a person who he will never see again. It’s almost peaceful.

“Everyone thinks that the monster in the woods got him.”

“Who’s ‘everyone’?” Steve knows, but he wants to hear it.

“Dustin, Mike, Will, Lucas… Jane.”

“How do you know it’s a monster?” Steve doesn’t want to focus on Neil. He knows that Max doesn’t want to, either.

“We don’t.” She says. “But they think it is.”

“What about you?”

“Hmm?”

“Do you think it’s a monster out there?”

“Maybe.” She says, head leaned back. “It can’t be all that bad if it got Neil. But, then again…”

She grimaces. Steve tries not to think of if she should have seen the body. Did she know before the news hit — or is that how she was told? A news reporter trespassing to get some ‘good content’. Surely it had only been described to her. They wouldn’t have made her see him, he reassures himself. If he thought that she would have had to see, he would have made it clean. Kept it hidden. Tried to make it look like she had just… disappeared.

“Yeah.” He says.

Max hums in agreement, eyes focussed outside, to the vast darkness of the woods.

“Do you think there’s it was a monster?”

Steve pulls into the driveway, parks. Thinks.

Does he think that he’s a monster? The easy answer is, well, yes. He’s killed people. He’s not fully human. There are parts of himself that crave the hunt that happens in the before. None of that really spells out anything but monster.

But he doesn’t want to scare her. He doesn’t want to scare any of them. Steve wants to keep them all safe, he realises. Even if they continue to think that there is a monster in the woods, even if they think that he is a monster, he wants to keep them safe.

He knows what he has to do. That wasn’t marker on Jane’s wrist. They were too-neat, too blue-faded to be sharpie. They were numbers. Which means that she knows the man, and the man knows her.

“I don’t know, Max.”

She studies his face, searching. Her eyes dart from his ears to his nose to his eyes, and she must find what she is looking for, because she is out the door with a nod, and the jangle of her keys as she lets herself in.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

STEVE HARRINGTON IS A BAD BOY ★ ( Wham! - Bad Boys edit ♫)

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

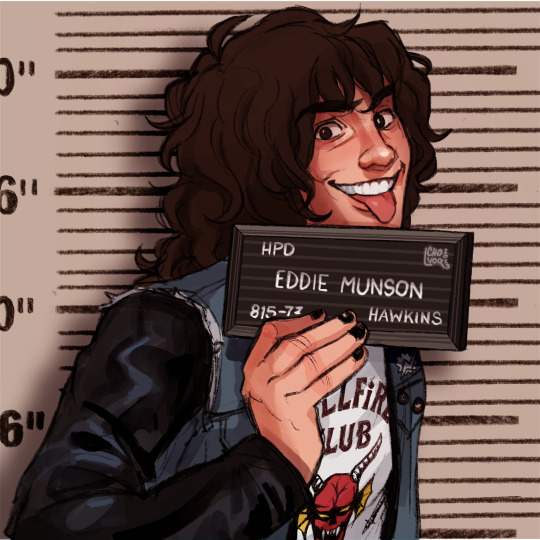

the one where steve is the monster in the woods: chapter 2

The dull fluorescent lights cast their sickly glow across the clinical cabinets — bouncing across the matte surfaces in the same way they do unpolished granite tiles: consuming all that lays before them, and barely giving anything back. They stay still on the ceilings, but it is a fickle thing, the way that they almost-flicker, no two lights the same. Circular and small, rectangular and long, acting as the sun for a curled up child who holds themselves on unsure knees, toes sticking to the tiles that they believe to be ruined. There is no upcurling of uncut, awkwardly and cheaply positioned bedroom flooring, but the curtains sag against their wayward souls; a curled child against their curséd sun, horribly still.

He doesn’t want to be here.

The man holding his hand is the same as always — with white hair that reminded him of Santa, and a warm smile that felt anything but. There was some sort of fictionality to him, as if he were trying too hard to appear comforting. Like some kind of uncanny-kindness that branded itself across his eyes, that had embedded itself into the smell of his coat. The man wants to be called a name that Steven does not want to repeat. The hand clasped around his palm is meant to make him feel better, and he doesn’t understand why it makes him feel sick. The door opens with an impressive creak, and Steven is deposited into the room with no windows and a large mirror.

The sound of shuffling behind the mirror, fingernails scraping across a table, a click of a button: “Proceed to the checklist.”

The checklist has always been there. For as long as he can remember. In his hand, on the wall, slipped under his door. He’s never completed it. Steven doesn’t want to be here, he knows that, he knows that he doesn’t want this. Knows that if he gives them what they want, then he will never be able to leave. He saw the way the other kids in the room were slowly carted off one by one — just like he was — for their weekly checkups. And Steven was cognitive enough to realise that some of them never came back. The small child with large eyes, the boy with blonde hair, the girl with the sloped nose.

Sometimes, late at night, he’ll dream of where they were taken. If they were the lucky ones that had escaped the lights and the doctors and Papa.

But, Steven thinks, if he does this, if he makes them happy, if he makes them write down the green ticks on their clipboards, he will be able to see his mother and his father, and maybe then will they want him.

— — —

It feels like everyone is fucking staring at him.

Steve knows that that isn’t true — because nobody would be able to know that what happened last night, that the body found in woods was his doing, that he had changed under the moonlight, after and during and before the Halloween party. It doesn’t stop him for being paranoid, though. Not when every turn he takes to get to his locker, to go to his classes, is met with the peering eyes just out of his vision. But Steve Harrington is not a murderer, a monster, in these peoples eyes, so there is nothing for him to worry about. None at all.

Except—

“How long d’you think Munson’s has been staring at you, Steve?” Tommy asks. And, really, Tommy H. is quite literally the last person that he wants to talk to right now.

“What?”

Carol squeezes herself between them, as if they were still pals, as if they weren’t dickheads. “I think the little freak has a crush.”

She says it in such a sing-song way that makes him think of her as a child. Teasing and pulling hair, and running to Steve about how Tammy and I kissed each other so we could practice for when we get boyfriends! Sometimes he wishes that she never changed. Or, maybe, he wishes that she grew up more.

“Well, now that little Stevie’s on the market, the queer probably thinks that he has a chance!”

Right. Nancy. The breakup. How he’s bullshit. Maybe that’s the reason that it feels like the entire student body is staring at him — trying to gauge if he’s heartbroken and sullen, or if he’s already looking for another chance with another person. The reality is, he forgot about it. Or, he would have forgotten about it if nobody mentioned it to him, because he was more worried about the dead man in the woods, and the way his skin seemed to break and stretch, and the voice inside his head that has been eerily silent since he cursed it out. He still can’t remember who he killed.

Tommy and Carol cackle to each other beside Steve, beside his locker, and a hum in the back of his brain tells him to punch them. Slam their heads into the metal of the locker. Hold Tommy’s hand so hard that the bones start to creak, and he gets that scared, wide-eyed look on his face that will inevitably end in a crushed palm, a sickeningly sweet crunch, tears and snot and blood and—

Steve raises his hand to press against the crown of his brow, pushing and pushing as if trying to invert his own skin. He lifts his other palm — maybe to push Tommy and Carol and their incessant squawking and squabbling (give in give in give in), and places it to his other eye like a man blind. He rubs harshly against his face in a way that would be seen as uncouth by anyone willing to watch, trying to rid himself of the violent-hungry feeling at the forefront of his skull. Smooth fingers meets smooth skin and the raised edges of—

A cut.

From last night, in the woods.

A cut on his cheek, from last night in the woods, that Eddie had given him.

He snaps his head around, looks over the sea of heads to find where Eddie is still looking, where he hasn’t stopped looking, at Steve’s face— no — at the cut on Steve’s cheek. But, no, it can’t be because of that, can it? Steve knows, partially, possibly, what he looked like when he was not himself. He knew that he did not look human. He knew that he had horns and no jaw and horribly inhuman proportions — he looked nothing like himself. And the cut, if you can even call it that, is barely there at all! His other skin had taken the brunt of it. So there is no possible reason for Eddie to be staring at the cut. No, he has to be staring at him because of the breakup, because of something else, something else.

(But, if someone knew where to look, it was fresh, and pink, and obvious).

“Fuck off, Tommy.” Steve says, hands by his sides, eyes glued to where Munson was standing before he retreated around the corner.

“Aww, has wittle Harrington gone soft—”

“Tommy.” Steve says, eyes turning first, head following a second later. If Tommy didn’t shut his goddamned mouth soon, Steve was going to show him how. “Fuck. Off.”

The two sneer at him as if he just pissed on their fancy carpet, and Steve may as well have. He needs to fix this. Steve needs to see if Eddie really knows — if he had figured it out, if he had told anybody about what what he thinks he saw — or if he was just as much of a gossip as the average teenager. But he can’t— Steve can’t just go up to him and say were you staring at me because you know that I was the monster in the woods, because you know that I killed that man last night? without completely, and utterly, outing himself.

The warning bell rings, the students scatter, Steve locks himself in a bathroom stall, and watches as the chunks of his breakfast swirl down the toilet.

— — —

First period passes too quickly. Sure, Steve’s never really been what you would classify as a star student, but he’s always been attentive enough that teachers haven’t faulted him for his work, and he’s been smart enough to not really have to listen in classes and still get mostly B’s. He’s never really enjoyed school, but don’t all teenagers? Isn’t that what makes him so normal and mundane, just like them? He’s never wished for class to go longer, but today, as he stands under the spray of the shower in the locker rooms in second period, he wishes that they did.

Hargrove mentions it on the basketball court. The girl who sits next to him in first period mentions it as soon as he places his bag down. He hears whispers of it through the halls, feels his hairs stick on end when the words reach his ears. And then, of course, there was everything that was going on with Munson, but one thing at a time, right?

“Did you hear, Steve?”

In their little group, Barb is the first one to bring it up during their break. He’s the last one to arrive — skin pink-kissed from the scalding hot water, hair damp and cold against the slight breeze. Nancy and Jonathan have nearly finished eating, but Barb’s food remains mostly untouched. It was one of those little quirks that she had — she said that it was always awkward when she was little and would show up to lunch late, and everyone else had finished. She would end up being the only one eating, everyone with their eyes on her, telling her to chew softer or drink quieter. So, whenever something would happen and one of them was late, they knew they could always count on Barb to join them.

It doesn’t make Steve miss, however, the hand that Nancy has placed within Jonathan’s. Their fingers are clasped together underneath the metal table, as if the piece of shitty furniture will stop Steve from seeing how deeply infatuated they are with each other. As if they hadn’t been pining for months, as if Steve didn’t feel the way that everything was slipping away from him. Nancy looks up at him from her empty plate as he takes a seat next to Barb, eyebrows furrowed, but Steve just smiles and nods and swallows his stapled heart.

“Did I hear what?” Steve asks. He already knows the answer, because it can only be one of two things: the man in the woods, or he and Nancy’s breakup. Judging from the way that Barb is looking at him with soft eyes but not pitying eyes, the way that she places her hand on the back of his and presses her thumb to his pulse in a soothing motion, he can guess which one she wants to talk about.

“They found a body of a man in the woods! It was all over the radio this morning. My dad says that it was probably just a bear or something, but my mum thinks that it might be something supernatural.”

“What, like bigfoot?” Steve snorts.

“No!” Barb says, and stabs her apple slice with her fork. “Okay, yeah, maybe. But wouldn’t that be cool? Hawkins’ own cryptid?”

“A man died, Barb. You can’t just say that it would be cool to have a Hawkins-branded-monster.” Nancy says.

“Maybe cool isn’t the right word, but it would make this town less boring, wouldn’t it? I mean, when was the last time anything even remotely news-worthy happened here?”

Jonathan turns his head to the side, and Steve can just hear the sound of his breath stilling, or the hairs on his arms standing upright and paralysed, because the last time something news-worthy had happened, it was his little brother going missing. Steve nudges Barb with his foot under the table, draws a little arrow on her skin with his finger tips towards Jonathan. He sees the moment that understanding crosses her face: the furrowing of brows, the wide eyes, the hunched shoulders. She didn’t mean any harm by the comment. Just, sometimes, words came out wrong, for her.

“Mike thinks it’s a monster.” Nancy says, her hand tightly squeezing Jonathan’s. “He said that his friend’s dad is on the police force, that they got a quick look at the body when they were still in the car.”

(Does he look different? Can they tell? He spent most of his classes picking at his fingers, looking at himself in the bathroom mirror, trying to see if he left something out. If he has a smear of blood across his hands, imbedded under his skin, his bones. Can he have one moment where someone doesn’t mention the dead man in the woods?).

“Monsters aren’t real.” Steve says, definitive, reflective. “Barb’s dad is probably right. It was probably just a bear attack.”

“Since when did we have bear attacks in Indiana?”

“Since forever ago, Jonathan.”

Jonathan snorts, and despite the weird almost-love triangle that’s going on between the three of them, it makes Steve happy to see him smile.

“Stacy in chemistry said that he worked for the paper,” Nancy says. “It could be a rumour but.”

She stops, as if that is the end of her line of thinking. Steve can see the cogs turning in her brain, listing all of the people from her and Jonathan’s internship that it could be. The janitors, the paper-boys, her boss, the board, the other interns, the secretary, front desk.

“Hey,” Jonathan says, leg lightly kicking the bottom of Steve’s shoes. “What’s his deal?”

Don’t be Eddie, don’t be Eddie, don’t be Eddie, don’t be Eddie. Steve turns around, slowly, as if he can fight it off, as if he can turn forever until the bell rings and they cart themselves back to the rest of their classes. It’s only a quick look that he spares, but it is enough to know — enough to confirm — that it is still Eddie who is peering at him.

He knows, he knows, he knows. He was there in the woods that night, he had seen, he had given, the cut on his face. There’s no way that he hasn’t figured it out yet, there’s no way that he isn’t going to confront Steve about it. But what can he prove? There is nothing to prove. There is no way that he can say that Steve was in the woods, because everybody knows, everybody else had seen him leave the party, and the lights were on in his house, and he had collected his car before anyone saw that it was still at Tina’s. There is nothing to prove, there is nothing that can be proven, so why does he still feel breathless whenever he spots Eddie’s eyes piercing though him?

“I don’t know. He’s been doing that all day though. Just… staring at me.”

“You haven’t done anything to piss him off?”

“Barb! You know Steve doesn’t do that anymore.”

“It was a valid question!”

“It’s alright, Nance.” Steve sighs. “But, no. I barely even talk to the guy.”

Barb snorts. “Who knows, maybe he thinks you’re the one who killed that man in the woods.”

“Yeah,” Steve says. “Wouldn’t that be funny.”

— — —

“If you don’t tell me how the fuck to deal with Munson right now everything is going to be fucked!”

Steve’s tried a couple methods, already, but the voice inside his head hasn’t responded to any of them. Not when he threatened to turn himself in, not when he pressed his palms close to his fireplace, not when he held his breath under the pool for as long as he could before breathing in as much water as his lungs could hold. It didn’t seem like the voice even cared about being caught, or for the state that his fleshy vessel was in. No, the voice didn’t care about Steve, didn’t care about what happened to him.