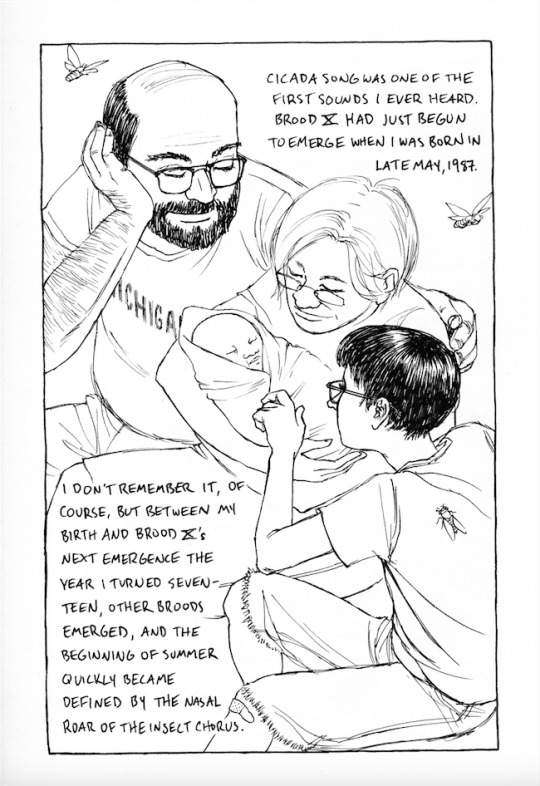

Text

Brooding

EJ LANDSMAN is a queer transgender artist living in Seattle. They create scientific illustrations of insects and plants, and comics about living with mental illness and other everyday struggles, all of which they share with the world at ejlandsman.tumblr.com. They want to be a crazy cat person when they grow up.

#ej landsman#comic#illustration#essay#essays#writing#art#experimental lit#litmags#zines#queer#cicadas#27#iamtwentyseven

89 notes

·

View notes

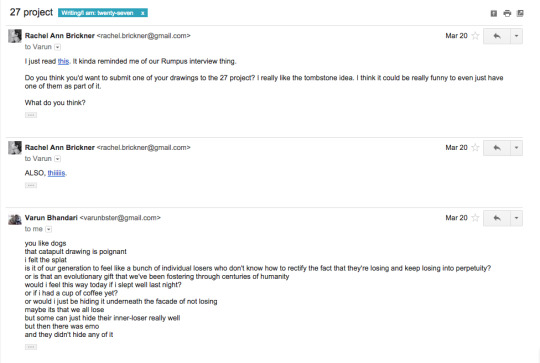

Photo

VARUN BHANDARI and RACHEL ANN BRICKNER

VARUN is a fart in human form and currently resides in Philadelphia where he types all day “making the Internet.” His dog, who is cuter than him, is named Ralph. He likes hoagies.

RACHEL is a human form of a turtle and cat missing link that creationists have been searching for. A true anomaly! It’s only when she’s caught licking her human paws that she retracts her head between her shoulder blades in shame but also in defense of an attack. She lives in Pittsburgh amongst bridges, ketchup, a cat named Faulkner (who is more human than she, by the way), and worries this piece was too vain for entry in her own zine. Who cares! She makes the rules!

^bios written by and for each other

hyperlinks: email one and email two

#varun bhandari#rachel ann brickner#creative nonfiction#email essay#essay#essays#writing#writers#experimental lit#litmags#zines#death#six feet under#mondays#27#iamtwentyseven

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I Quit My Job

It creeps up on you. It begins with your running routine tapering down to two days a week, one day a week, non-existent. Then there’s the increase in take-out food, which becomes your vice of choice. You tell yourself that you love going to bed at 7 PM, finally a schedule that fits you! Your friends work around your odd available hours, but you still start finding excuses for not being able to hang out.

Your long walks with the dog disappear. Turn into a block. Then to the lot across the street. And then you just start forcing him onto the back patio while you stand in front of the microwave, staring at the plate of stale pizza spinning in front of you. He starts having accidents. What the fuck is his problem, you ask yourself. He seems really bummed out. Didn't you read an article somewhere that said that pets mirror their owner's emotions?

You notice a new softness in your middle and your jeans start to wear in the crotch. You look at yourself naked in the mirror and things sag more than they did before. Your shoulders set the tone—they slump first, everything below follows suit.

Showers happen when you feel like getting out of bed to do it. You don't brush your hair afterwards, you just crawl back into bed in your robe. You wake up with kinked hair. You brush it briefly. You don't really care.

You sleep in every morning. You do not do your makeup. Often, you don't even put deodorant on. You are late to work nearly once a week now. Your clothes are tattered and reek of cigarette smoke and sour laundry. You smile at people, but no one engages you. At work you catch glimpses of your reflection. What a wreck, you think.

You drink, and you drink and you drink and you drink when you drink. You wake up with a fuzzy head. You felt good smoking that cigarette in front of the bar, laughing with your friends. You feel awful the next morning, afternoon, and evening, throwing up bile until 6 PM, a sharp and pounding pain in your head that is only relieved briefly when you're heaving into the toilet. But it returns tenfold as you crumple into yourself. You've called off of work again.

You have boyfriends. They provide temporary respite from the mundane day-to-day. They are fun—you go to bars, you go to dinner, you go to the park. They hold you and they tell that you are sweet and a little sad.

Once in a while you have a day off where you pay your bills, or you visit your grandma, or you clean your room. You end the day looking out the window introspectively. See! You can center yourself, you say. You go back to work at 4 AM the next day and chaos returns.

The toxic thing about the burn out is that it's these little omissions and exceptions, and they happen slowly, and you justify each downward step. I'm tired. I'm making good money. I've just got to prove myself to get to the next step.

When you finally decide to pick yourself up from it, you look around and find that the mess is much larger than you had thought. You put yourself a safe distance from alcohol, clearing your head just enough to realize that those hangovers are not the root of your unhappiness. You give yourself enough clarity to fall for someone whose company you enjoy outside of the neon glow of the bar. He expresses concern, not frustration. You apologize as you cry into the receiver when he calls. I'm going to make myself better, you say. I believe you, he says.

You ask for help at work. You tell them how hard things are for you, why you are struggling. You gave entire parts of yourself up for a job, calling it a passion but realizing in your misery that it’s okay for a job to be nothing more than just a job. It can just pay the bills and put gas in your car and pay for some nice things every now and then. You say to them, I don't want to give up, but—

The people you ask are trained to react with disconnected sympathy. They say, we don't want you to give up, either! They ask, but what are you doing in your personal life to cope with work stress? They say, we really think you need to adjust your attitude before you can move on from this position.

And you go home and you cry yourself to sleep at 1 PM thinking that maybe the word "passion" doesn't belong in the corporate workplace. And you wake up a few hours later, and you get on Craigslist and you say fuck it and you send your resume out and just like that, they email you back and just like that, you take a new job.

You told yourself that you were going to find something great. Your friends and family always asked, how is the job hunt going? You say good, I guess. But the hunt was just brief spurts of applications to positions you knew nothing about with long stretches of inactivity in between. The truth was that it didn't exist, you were too afraid to move. You'd settled into your own miserable place and you feared change more than you valued happiness. But you took that new job, feeling your back up against the wall, and you tearfully told your boss that you quit.

You imagined how your resignation speech would go. You dreamed of the freedom that it would bring. But you walked out the door of the office and into the bathroom and sat on the toilet and heaved. Heavy, sad sobs. Where was the relief? Your friends congratulated you, begged you for celebratory drinks. You felt overwhelmed. You were not, just like that, back. You had altered yourself so severely that the person you wanted back wasn't going to just appear and slip into your skin comfortably. Your return to normalcy, you found after your two weeks notice, was going to take some time.

You can feel it, every now and then. You cook yourself nourishing food. Your laugh has deepened and people respond positively when you approach them. You play with your dog. Your strolls are still short, but if his mood is truly reflective of yours then you can give him the type of comfort that you long for. You take an impulsive trip to New York City with the boyfriend who matters, refreshed even as you sit in traffic on the Verrazano Bridge. You moisturize your cracked hands and brush some mascara on every morning, but you’re still tired. In between public bouts of tears and entire days alone in bed, you're still there. It's just taking a little longer than you had expected to find you.

KATE RATH is a 27-year-old in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. This is her first published piece outside of the blog that she maintains so her dad can follow her writing. She has a pet cat and a pet dog.

#kate rath#creative nonfiction#essay#essays#writing#writers#literature#lit#litmags#zines#27#iamtwentyseven

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Others’ Memories

Editor’s note: The names of the author’s parents have been changed to protect their privacy. M (Michael) refers to her father, A (Anna) refers to her mother, and D refers to Ms. Levsky herself.

D: I recall memories that are not my own. They live and breathe in the minds of my parents, my Mama, my Papa, and resonate in HD picture through my mind. I grew up with stories of waiting in long lines for toilet paper in the Soviet Union, of camping adventures through Ukraine and farm volunteer hours in Russia, of how my parents came to know each other at 13 and love each other at 20, of my family’s departure to America, of how happy this country made them. There are certain images that are permanently entangled in my own recollections; they are so vivid, so real, and yet, they are just stories.

M: We were both on the cusp of turning 27 when we left the Soviet Union. That was 1992 and it was a very interesting year. Like everyone else who declared his or her departure, we were fired from work pretty quickly. Most of the year was spent selling off things from our apartment. We sold the cabinets, Anna’s favorite bed. Most of our advertisements were plastered on the bus stop sign when we didn't have enough to put one in the paper. Anna cried when we sold that bed.

We sold somany miscellaneous things. Just anything and everything we could. Buckets, chipped cups. People were willing to buy this junk because there was barely anything to be found in the supermarkets. Lines around the stores would last four, maybe six hours, and all for a gloriously overpriced stick of butter. So we sold everything. Not for much, but we were able to get by.

Buying anything was so expensive. The prices were just insane. I can’t even explain how expensive it was just to buy some vegetables. No, wait; yes, I can. We sold almost every component of our kitchen: the chairs, the table, cabinets, closets. For that, we were able to get my purple winter coat. It’s the same one I use to shovel snow in now.

A: I cried when we sold that bed. I had never slept on a more comfortable bed in my life before. The mattress was this rouge color, from Czechoslovakia. It molded to our shapes perfectly. Later, when we moved here, I learned that what I had been sleeping on was essentially a sofa bed. For that pink futon, I got a single pair of shoes.

Michael’s father made us a bed. Back then, we saved up all of our glass bottles. You could go to the store and exchange them for pennies. There, his father exchanged the bottles and also found some wooden crates that he fashioned into a bed for us.

My 27th birthday was March 4, 1992 and we arrived in America on April 27, 1992. In March, we had to make all of our travel arrangements. The plane tickets from Moscow were already paid for, but we had to pay for the suitcases, the train ride from Kiev, and a taxi to the airport in Moscow.

So many people were leaving the Soviet Union at the time that train tickets were hard to come by. It was slightly terrifying, because on the taxi ride from the train station to the airport, a lot of people were mugged, robbed, and even killed by bandits. There were gangs who understood that these people were leaving with only their most prized possessions, but when those prized possessions didn't serve any monetary value, they just took their money and killed them.

One of our friends referred us to what we knew was another gang that offered safe passage from the train station to the airport for an exorbitant price. If, say, a taxi ride cost 100 rubles, these personal rides cost 1000 rubles. It was a very interesting moment because we had no idea if we were actually going to be taken to the airport or if we were going to be sold off to the other bandits. When we climbed into the private vehicle, it was Michael, my mother, and my very sick father. I guess all you could do was pray to your God that nothing terrible should happen.

When we arrived in America, we realized that we would have had nothing to give away to those bandits. We might as well have brought empty suitcases, because all we ended up using was toothpaste, soap, the kitchen coat, and the sofa-bed shoes we brought.

M: Almost after we arrived, our friend Misha, who had been in Chicago for a year now, called me up and started badgering. “What are you doing, not working? Think you’re walking around like a free man now, eh?” He set me up with a job as a pizza delivery boy.

We all lived in one apartment in a building on Touhy. I worked most of the evening shifts in the bad parts of town. Anna would worry. Her mother would worry more. When I came home, they would tell me over and over again that it was time to quit this job, that it was dangerous. Then, we would all eat the delicious pizza I brought back and complain about eating so late. We repeated this process over and over again, every night until the middle of the summer.

With the money I earned, we went to buy our first car. No one in the Soviet Union really owned cars. At least, no one that lived within a 20 mile radius around us did. I took driving lessons just before we left Ukraine so I already knew how to drive and just had to pass a driver’s test here.

The first time we went to a car dealership, Anna was in tears again.

A: The car dealership was one of the most beautiful things I had ever seen. No one had cars in the Soviet Union. I mean, some people did, but they were smuggled in or a gift from the corrupt government. None of them were obtained in a normal setting. But this wasn't one car, it was many cars, maybe even hundreds, just standing there and waiting to be bought. I felt as if I had landed on another planet. Michael was touching the cars, he even sampled a ride in a bright green Cadillac.

This couldn't have ever happened there. If a car dealership opened up in the Soviet Union, they would have been stolen altogether or had parts removed from them within a day. There would be nothing left of the lot.

And it wasn't just the cars. It was all the stores. All the merchandise, the groceries. I got lost in an Aldi the first time I went inside. I was so fixated on the different pastries, cookies, trying to differentiate the prices at the beginning of the store that I was separated from the group and couldn't find my way back out of the store.

One of the first things we bought in America was an iron. In Ukraine, it was a necessity to have an iron, because all the clothes were made with pure cotton and we had no dryers to speak of. Here, with synthetic materials woven into our new clothes and dryers readily available on every corner, we never ended up using the iron.

M: American food was very strange and very exciting to us. For the first few months that we were in America, we received food packages because we were considered refugees. Most everyone in our building was Russian, except for an older Korean couple who also received the packages. Each package contained an enormous quantity of peanut butter, which we had never tried before. Everyone in the building agreed that it was disgusting.

Anna tried to do something about it. She found a recipe on the jar of peanut butter to make pastries and decided to give them a try. After handing them out to the entire building, she discovered that they were totally inedible and disgusting. We ended up throwing so much of it away.

We didn't go to many restaurants, but finally, on my 27th birthday in September, we went to our first restaurant: McDonald's.

A: I hated McDonald’s. I had just found out I was pregnant a month before and so I had become overly sensitive to smells. McDonald’s smelled just terrible to me. So did every smoker we passed by on the street.

We somehow managed to clothe ourselves and furnish the apartment, too. As refugees, we were welcomed into a secondhand store where we could get a bag of clothing for free. The owner of the store took a shine to me and insisted I try on fake fur coats, one after the other. Perhaps the coats came from the same source, but they were all incredibly short on my arms. We took one just to appease him. It was actually very fun being able to pick up new clothes without having to worry about our budget.

Furniture we knew we would have to pay for. So, instead, we resolved to drive around at the end of the summer, looking for couches and chairs that others had disposed of to make room for new furniture. For some reason, we would always happen to be out collecting furniture when it had just rained. We picked up a couch, moved it into the apartment, noticed a terrible smell, and then would heave it out the fifth story window towards the dumpster. We did this five times and had even more fun than with the free clothes.

D: When my mother was pregnant with me, she turned down a job to work at a chemical laboratory and started taking English classes at a school in Uptown with my father. They were awarded a grant for refugees and were able to save some of their class money for food and rent. My mother told me that she had never had a professor as brilliant as the one who taught her English. He not only knew the language well, but he savored teaching every word and reveled in the success of his students. While I was growing inside her womb, she was taking in every passionate lesson from this man. In a way, I’d like to think I was taking it all in, too.

DANIELLE LEVSKY currently lives, writes, laughs, and cries in Chicago; most of the time she works as a graphic designer and copy editor for the Chicago Tribune. She holds a B.A. in English Writing and a minor in French Language and Literature from the University of Pittsburgh. Her work has appeared in numerous online and print publications. Learn more about the Russian redhead at dlevsky13.wix.com/daniellelevsky.

#danielle levsky#interview#interviews#writers#writing#memories#soviet union#kiev#america#chicago#ukraine#russia#27#iam27#27yearsold#litmags#zines

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

False Light

Josh Mayfield has retired from professional baseball, and now my half-brother is older than every player in the major leagues. As a kid, he tells me, he didn’t believe he’d ever grow as old as Pete Rose or Lou Brock. At thirty, he tells me, he still saw a handful of warhorses as old men—Hershiser, Gwynn, Ripken. Now Josh Mayfield has retired, and James isn’t a kid anymore.

I remember July afternoons when he was on break from Kent State, my mother filling prescriptions at Prairie Pharmacy, our father filling cavities at the health center. James would toss wiffle balls over a home plate of splintered plywood while I swung a yellow plastic bat with all the grace of a wounded mule, my naked toes twisting around the stems of dandelions. Mom and Dad would come home within an hour of one another, and we’d eat a supper of corn or salad or grilled tilapia. Between mouthfuls of asparagus, James imparted the outcomes of his new education. Actually, he’d say, Foucault believed that Marxist thought belonged solely to the eighteen-hundreds. In the evenings we watched baseball in the garage, our father tinkering with the lawnmower engine, and James, beginning that one summer, draining a six-pack of National Bohemian over the course of nine innings.

Now, three weeks before his divorce, James smokes a pipe on his back patio. A new habit, he says, and he can’t seem to keep the tobacco lit, burns through match after match. My fiancée and I sip coffee from identical green mugs: we are visiting from our apartment in Champaign, two biologists in love. The yard is broad and flat—a nice, country yard. An early snow has fallen, and through a threadbare string of maples at the edge of the property, I see the neck and antlers of a young buck rising from the earth. The sky paints the air gray. James lights another match against the striker of a matchbook, dips the flame into the bowl of his pipe. Charring light, he says. False light. Just drying the strands.

We talk for a while about pipesmoking, about cheesemaking and pottery. I lay my arm across Angela’s thighs, and she traces circles on my palm with her fingernail. James asks about her dissertation, and she straightens in her seat, offers a few words about biofilm and aromatic degradation pathways. I watch leaves descend from the trees, somersault like gymnasts through the air. James and Angela talk, and I think about autumn. This autumn, last autumn, my first autumn in Illinois, when I toasted the Alma Mater and drank wine from a paper cup. I think about future autumns, when Angela and I land VAPs in the Northeast, when some Research-I bio department takes me on just so they can have her, when we marry in her Iowa hometown, beneath a crown cover of orange and red leaves. (Sometimes, scrutinizing a peach at the Urbana Saturday market, she bites her bottom lip hard enough to break skin, and I could kiss her for millennia.)

Let’s replenish our cups, James says. He taps his cashed tobacco into an empty coffee tin. Inside, a few cardboard boxes sit next to the refrigerator—his wife’s china, inherited from her grandmother, Virginian stoneware, the toaster. James fills our mugs from a carafe of French roast, says he’ll brew some more. We sit on barstools at the island and nibble from a bowl of cashews. You still into model trains? he asks.

I don’t have the space, I say. For a moment I remember detailing boxcars with dirt gathered from our mother’s garden, adding graffiti tags with a gel pen. I remember James, home from his postdoctoral residency, walking down to our father’s basement, nodding at the display, saying, Not too shabby. I envied him then, his life in the classroom, in books and in bars. I envy him still.

My half-brother pours two shots of whiskey into his coffee, apologizes. It’s eleven-thirty in the morning. He loves us, he says. I hold Angela’s hand in my lap, and she touches her shoulder to mine, traces her fingertip around the rim of her coffee mug. James looks through the bay window above the sink, out over the cold, wet lawn. He jangles the keys in his pocket. Otherwise, the sound of this room could put you to sleep—a sloshing dishwasher, a gurgling percolator, the purr of a furnace through baseboard registers. I watch James, whose eyes don’t move from his backyard. His thin, grim mouth and the flecks of silver in his stubble.

Your house is gorgeous, Angela says. With a paper napkin, she daubs droplets of coffee from the countertop. She looks down as speaks, uncrosses her legs. I wonder if he’ll live here much longer.

James sets his mug in the sink, takes a moment to tuck the hem of his shirt into wrinkled khakis. He sighs, and the sigh sounds affected, almost theatrical. Put on your coats, he says.

He wants to take us to the model train show at Second Presbyterian, held the third Saturday of each month, a little display in the basement, a few lonely enthusiasts who ache to share stories of watching diesel engines on the Ohio Southern thirty years ago, covering their ears at the brassy horns. A short Saturday afternoon jaunt, he says, and then we’ll return home for a venison roast (courtesy of a neighbor down the lane), for wine and duck pâté. I scratch the skin beneath the wool cuff of my sweater.

In the driveway, James and I wait for Angela to finish in the bathroom. He examines the chamber of his pipe, holds the device with two hands. Leaves are snow-pasted to the front windows of his house, to the dark shingles of the roof. He slips the pipe into the front pocket of his coat—a corduroy coat with a furry collar that reminds me of our father. Got damn cold, he says, and I nod into the wind. A blue Ford Explorer passes on the street, which winds past sloped lawns and maples and small firs, past houses of brick and broad windows. After a minute, Angela opens the front door and lowers her head to the cold air; she shoves her hands into the pockets of a dark pea coat. Through wind-flustered hair, she smiles at us, and for the first time, her smile seems crooked, maybe a little beguiling.

She takes the front passenger seat, and I sit behind her, studying the long strands of her dark hair, the flush surface of her cheek. James waves to a neighbor and a bullmastiff that pulls on its leash and sniffs at the roots of young elm. I rest my temple against the window and look upward, try to focus on a single leaf above me, one orange or yellow appendage on the boughs stretching over the road. But the car moves too fast, and they run together like spilled paint.

PHIL ORTMANN lives and writes in Pittsburgh. He holds a B.A. in English from the University of Pittsburgh and an M.F.A. from Penn State, where he cofounded the university’s first literary yearbook. His work has appeared in numerous publications and has been awarded an AWP Intro Journals Project award.

2 notes

·

View notes

Audio

LINER NOTES

BACK AT THE SUN - an expression about the reality of aging and the fear of not living up to my fullest potential while at the same time denying that my behaviors and circumstances are the cause of falling short.

ESPLANADE - a song about a middle aged woman who projects all her hope and passion for life onto a man. "Will you dance the esplanade when he comes back to you?" A realization as much as a question, it became clear that even if the event that took this man away hadn't happened, that passion to live "to dance" would probably not be there.

IN THE MUD - two lovers past that joyous and youthful explosion of the initial infatuation are faced with their first hardship. The first questions why everyone would applaud their love, a seemingly fated event, and equally feels lost by the "rules" that others have for love, so much so that it causes doubt about the love. The second attempts to ignore the new circumstances "she tries to keep her eyes off the pain" but she knows that the hardships are true as she's already spoken about them in relation to her definition of love. Too late to go back now, time to move forward and allow room for growth.

LULLABY - a simple love song for the setting sun of youth and a literal message and prayer to a world weary friend.

NOWHERE TO GO - "I've dreamt this presence for too many years." By 27 I was beginning to feel the weight of the perceived chaos of shackled fate as a truth I was denying for my entire life but could no longer look away from. Terrified of the possibility that we have no real choice in life, I lamented over the question of where do you go from this state of mind?

SUCH A FOOL - a heart feeling remorse for venturing back to old streets in a vain attempt to recapture a time long gone. The streets once were well lit, but the sun has long since set on this place and to go there now is to choose darkness over the light of the present.

UNDER BELLS AND BIRDS - the last of the songs recorded in this short collection felt like a rebirth guided by actual birds and church bells that happened to be echoing in the background as I recorded. The refrain comes back to the questions asked in "Nowhere to Go." "How do you deal with someone else behind the wheel?" Both a recognition of the lack of control perceived over my environment and an acceptance that the person I am now was not the person I was even a few moments ago. So, how do I deal with this new set of perceptions, this new persona behind the wheel? Almost 5 years later, I'm still searching for answers to that question, but maybe less so for a definitive answer, and more so with an excitement that a new answer will always arise.

DEWDROP MIND is a singer-songwriter cloaked in indigo child anonymity. He began recording songs on his laptop in the basement of the childhood home he boomeranged back to as a quasi post-grad far-in form of self-exploration and deprecation. Nearly a decade later dewdrop mind continues recording low-fi spontaneous introspections as audio memoirs. He currently lives, loves and writes in Venice Beach, California.

4 notes

·

View notes

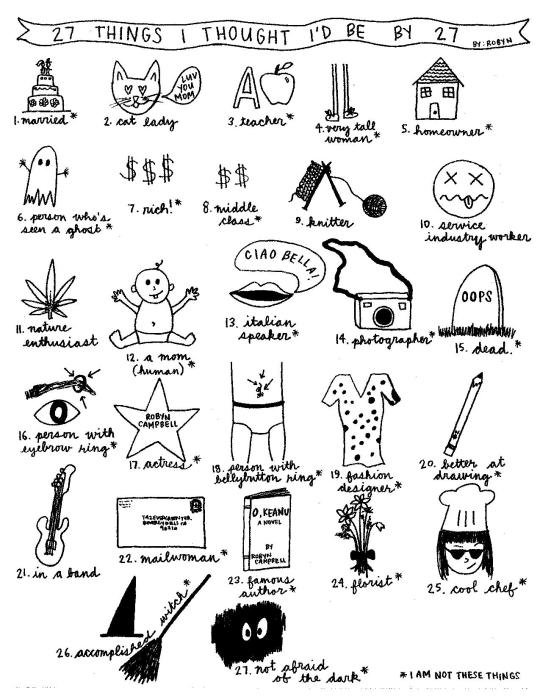

Photo

ROBYN CAMPBELL is a Pennsylvanian Pisces living and working and playing in bands in Philadelphia. Her poems have appeared here and there (details at palmsideup.tumblr.com) and her first chapbook, Bloom Where You, is currently available. She also edits Semiperfect, a zine of short works. You can reach her at [email protected]. But who cares? The important thing is that her birthday is the same as Kurt Cobain's and she is about to turn 27. Insert your favorite Nirvana quote here.

#robyn campbell#essay#comic#micro-essay#writing#writers#literature#lit#litmags#zines#27#iamtwentyseven

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Favorites

I enrolled in Russian 101 five falls ago, eager to learn what children’s books looked like in a Cyrillic alphabet, ready to sing pop songs in a language that made me feel like I was chewing on marbles.

We learned how to talk about cities first. The professor was a small woman with wiry hair. Gorod! she chirped. City!

Gorod, we agreed.

She asked us what our favorite cities were. I listened as the rest of the class went through the names of their cities, pronouncing them in cartoonish accents. Sahn Franseesco! they shouted. Denvair!

Don’t laugh, our small professor said. Moy lyubimiy gorod is Cleveland.

Cleveland! the class shrieked. Students tried out their new accents. Cleeevelaahnd.

It was my first love, the professor said. My first home in the U.S.

We all nodded, suddenly solemn. I didn’t know what to say. Did I say Portland, a city where I had lived too long? Or New York, where I didn’t quite live long enough? I didn’t know how to choose, how to reconcile one place over another. I had no lyubimiy gorod.

I decided on Vancouver, a place in which I’d never lived but had always admired. My dad was born there. It was always night, always raining, but the city loomed silver and green during my handful of visits. By no means a first love, just a crush. I could pronounce it in my new accent. Vancouvair, I said, nodding to the professor. She returned the nod and moved on to the next student.

REBECCA OWEN lives outside of Portland, Oregon, with a rescue dog and a rescue horse. She received her MFA from Minnesota State University Moorhead. There, she learned to tell the difference between twenty degrees and twenty degrees below zero. These days, she teaches writing courses at a community college, plays the cello in a local orchestra, and is working on a book about old horses. Her work has appeared in Oregon Quarterly and Equus.

#rebecca owen#portland#cleveland#vancouver#russian#essay#micro-essay#flash nonfiction#writing#writers#literature#lit#litmags#zines#27#iamtwentyseven

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pre-deployment

Blake and I had eaten our supper and settled in on rough upholstery in the living room. Blake sat up, attending to reruns of Family Guy, Futurama, or King of the Hill, while I nestled against the worn denim and soapy scent of his favorite Silvertabs, savoring the scent while I could, knowing that at any moment comfort could be washed away in a wave of nausea. In the early stages of pregnancy, I was learning a new vocabulary and extending definitions. Morning sickness was not confined to mornings.

Blake was learning, too. He paced the living room until I emerged from the bathroom after each wave of sickness. His eyes weighted with guilt, he would ask if there was anything he could do. He had learned to choose restaurants that offered a salad bar, so that at least if my stomach turned when my entrée reached the table I could find something to eat. So as we settled into our evening, he tried to stifle his laughter, hold his body still so that I could rest. His fingers followed the curve of hair along my temple. The ground outside lay frozen beneath thick snow, but inside I curled into Blake’s warmth, allowed his hollow laugh, muffled by flesh and fabric, to slow me into sleep.

But then something wrenched me awake: the smell of sienna powder; the sight of it dusted over apple slices sparkling with sugar; the soft flesh of caramelized fruit buried beneath crisp brown-sugar-and-oatmeal earth; the taste of it all blending, bleeding syrupy, cinnamon sweet. The craving had hit, and suddenly I felt myself springing from the couch, frantic for fulfillment.

I moved with such urgency that Blake followed instinctively, his long stride matching mine until I lunged at the fridge. He paused at the edge of the kitchen counter while I clawed at the fruit drawer. “Apple crisp,” I explained. “I’ve got to have some.” I watched his wide-eyed panic transform into a pinched confusion as I asked, “Do you want some?”

“Apple crisp?” His voice softened into a near laugh, his head bobbed in disbelief, “Apple crisp? No, no thanks.”

He left the kitchen and fell back onto the couch, legs stretched over cushions, arms tucked in at his sides, while I frantically peeled red-streaked yellow skins with a flimsy paring knife, filling a bowl of salt water with yellow-white apple moons. I checked the recipe scribbled in the back cover of a family cookbook, then pulled a chair to the stove front and stepped up to scour for ingredients inside the white, pressed-board cupboards.

After a few moments, my disbelief bubbled over. “You’ve got to be kidding!” The urgency in my voice jerked Blake back to the kitchen, where I continued digging through cookbooks, bags of flour and sugar, and plastic shakers of seasonings and spices in the baking cupboard. His wide eyes anticipated an emergency as he asked, “What’s wrong? What do you need?”

“Cinnamon. I’m completely out. Can you believe it?”

He smiled, lowering his brow as if reasoning with a child. “You mean you can’t make apple crisp without it?”

Something about the way I scowled, the way my shoulders dropped as my hands clung to the lip of the cupboard, the way I shrieked disbelief must have communicated the urgency of pregnancy cravings, because before I could answer, Blake was at the door, lacing his hunting boots. I moved to the frosty sliding glass doors that led to the deck and watched freshly falling snow fill the dotted-line his heavy boots left behind as he made his way across the parking lot to the convenience store to see if they sold cinnamon.

Watching him leave, I wanted to cry, because even though Blake and I had grown up in the same small town and had attended the same church and school all our lives, even though we’d said many goodbyes and spent months and years separated by state and country lines, watching him go—even across the parking lot—reminded me that he would be leaving again soon. Sometime after the wedding we’d scheduled for Memorial Day weekend 2005, probably before our baby’s October due date, Blake would be going to Iraq.

Seven years earlier, on New Year’s Eve, Blake and I walked together across a snow-covered driveway, abandoning a noisy party for the familiar, tight space of his dad’s dusty pickup, where we could speak softly, let our words linger like the smell of cigarettes in the worn upholstery. We’d spent many nights in that truck, driving around with his older brother, Brock, a case of Old Mil light, and piles of our favorite CDs. But that New Year’s Eve, we were alone.

Blake and I were rarely alone together. We spent time with friends, drinking in the dugout after summer baseball games, sometimes skinny-dipping in the pool in the middle of the night, or watching TV in his grandparents’ dairy where we slouched on rusty folding chairs surrounded by animal pelts and camouflaged jackets. I’d had a crush on Blake since junior high, when I watched his 7th grade basketball team play while I waited in my short blue and gold pleated skirt to cheer for the 9th grade game, so I wasn’t surprised by the way Blake and I tended to drift away from parties and into our own intimate conversations. I was surprised, though, that our friends noticed so quickly and began to ask, “What’s going on between the two of you?” I didn’t have an answer, yet.

In the truck, I leaned across a console filled with gum wrappers and change, a shotgun angled against it. My thin fingers dangled from the faux-leather console, fluttered just above Blake’s knee as he asked me about the literature classes I was taking in college. “Did you know rye was one of the staple foods in Salem and other places where people went on witch hunts? Some scholars think that the ‘bewitched’ women were really just high on fermented rye.” Blake was always up for a discussion or a debate, so he egged me on and challenged my newly acquired ideas. “Or maybe they were really witches that just happened to eat rye.” I loved the way his eyebrows peaked playfully as he questioned me, but I had questions for him, too.

“So, what about you?” I asked. “Why aren’t you going to school this year?”

“I’m joining the Guard,” he said. “Basic training starts next week and then AIT.”

The answer surprised me, even though it shouldn’t have. His older brother, Brock, was in the National Guard, and Blake had mentioned the possibility before. I squinted at Blake through the dark and asked, “You’re sure you want to do that?”

“Yeah, I’m sure,” he answered.

“I’m not saying it’s a bad idea,” I back-pedaled, trying to look into his downturned eyes, “it just seems like a big deal. What makes you so sure?”

“Because I have no idea what I want to do or what I want to be.” He traced the seam of his Levi’s. Then he looked up, but not at me. He looked through the windshield and said, “I’ve always known I would join the Army. I just know I can be good at this.”

All I could imagine of military service was camouflage uniforms and weapons. I’d never handled any kind of gun, except for the time my uncle took my cousins and me out to the slough by Grandma Evie’s and showed us how to fire a pistol. But in the dairy on a summer night I’d watched Blake meticulously piece a rifle back together after cleaning metal pieces I had no name for. I knew he was comfortable with guns. “So you aren’t going to go to college?”

“No, I will,” he said, “just not until fall.” My breath hung, visible in the January cold, as I wondered what to say next. After so many nights, so many conversations, and Blake still at a safe emotional and physical distance, it seemed significant that he was sharing these plans with me. But I remembered my cousin’s wedding reception six months earlier, how Blake placed his hands over the royal blue lace of my bridesmaid’s gown but held his forearms stiffly between us while the chords of “Desperado” carried us from side to side, how he pulled me towards him for an unexpected, rigid hug during the final note and whispered, “You look beautiful,” and then disappeared for the rest of the night. He seemed comfortable now, and I didn’t want to scare him off. So I held words and breath in my chest until Blake surprised me with an audible exhale and the words, “It would be nice to have someone to write to while I’m gone.”

The first letter with a return address of Fort Sill, Oklahoma, arrived a few weeks later. Back at South Dakota State University for spring semester, back in the four bedroom apartment I shared with four friends from high school, I tore the letter open in the kitchen and I read my way down the hall to my corner bedroom. The letter was short, one small sheet of unlined Army stationary. Blake was fine. Basic Training wasn’t as hard as he thought it would be, but he wanted me to have his address in case I had time to write.

I had time. I wrote a letter immediately, posted it the next day and began a daily mail check, anticipating another envelope from Fort Sill. When it finally came after two weeks, I blushed as my eyes flittered over his apology for being too busy to write and his appreciation for my letter. That was enough incentive for me to write more regularly. Letter after letter on the same college ruled paper. Summaries of every experience I thought might make him laugh, every idea he would engage if he were there with me. When I read Trainspotting and A Clockwork Orange in my Contemporary British Lit class, I wrote a casual critical paper for him, knowing he would have seen the movies and would add them to his list of novels he should read someday. When a Far Side joke from my desk calendar made me laugh, I tore it out and folded it between pages of blue lines and my erratic combinations of upper and lower case letters, cursive and printing.

Blake’s letters and postcards came intermittently, but I read and reread them every day, hearing his voice in my head as I followed the crooked lines of his choppy cursive. “Amber, I know I promised you a letter,” he wrote, “but this is a big postcard.” It was a big postcard, a 5x7 picture of illumination flares going off at night. I laughed when, after a couple sentences about the weather and the frustrations of downtime on an Army base, Blake wrote, “I know this is pretty crappy, but I’ve already put a stamp on it and have written some, and I don’t think I’ll have time to write another.” I’m sure my smile softened and my fingers curled over my collarbone as I read on:

“I thought a lot about home today and for the first time I was homesick. I forgot to lock my locker and caught it before I left when I needed to get my gloves. I said to myself, ‘Blake, what are you doing?’ It made me feel good because it’s all last names here and that is what I used to say to myself at home. So, you can imagine how nice your letter was.”

I flipped the postcard over in my hand, savoring the last sentence. I studied the postcard’s orange flares, the quote appearing beneath them in small caps. “A coward dies a hundred deaths, a brave man only once; but once is enough.” I knew Blake would have noticed the quote, because he always noticed everything, always planned his words and actions carefully. I wondered if he imagined himself a coward. I remembered “Desperado.” Blake had always insisted we end a night of beer drinking with that song. He always sang every word, and though not on key, he followed every slide from note to note. I suspected his letters were an attempt at bravery.

I could be sure after the next postcard came. Blake wrote that he was preparing for a 21 task test, but that he wasn’t worried because “the Army is set up for the stupidest man alive.” Then he added, “Speaking of witch,”—and yes, he did confuse the homonyms—“are you seeing anyone from class or anything?”

With hundreds of miles and three states between us, Blake’s letters slowed my breathing, drew my eyes shut so that I could feel his presence. I fell asleep at night with a pen in hand, the spine of a notebook pressing into my cheek, Blake’s letters beside my pillow. In my dreams, Blake and I were like World War II couples I’d seen on TV or in media images—white-capped soldiers kissing young wives in fur-collared coats on the pier. A couple drawn together by military service. I had cast myself in the role of his something-to-come-home-to.

A few months later, on the 4th of July, I was the one coming home to Blake. That summer, I had crossed my first international border, traveling to Oaxaca, Mexico for a month-long study-abroad trip. In Mexico, I felt my world expanding suddenly as I learned to communicate with street vendors and the bouncers and waiters who worked at the disco my friends and I visited on weekends. By the time I returned to South Dakota, I’d changed my class schedule for the coming semester, having decided to double major in Spanish and English. But I’d also spent hours in Oaxaca scouring souvenir shops for gifts for Blake and his brother, Brock.

I returned home just in time for the 4th of July street dance, where I presented Brock with his volcano-topped ashtray that funneled smoke from stubbed out cigarettes through the top of the snow-tipped mountain, and Blake with his bottle of orange flavored Mezcal. Blake and I spent the night sneaking to my car to drink shots of the stinging alcohol. By 4 am, he had drunk the worm, and the two of us had found our way to the baseball field, where we stood under a cottonwood at the entrance to the park.

Blake laughed nervously as I wrapped my arms around his waist, then he squeezed my bony hips with his thin fingers.

“So, what is this?” I asked. “What’s going on here?”

Blake pulled me towards him and we hugged like awkward kids at a junior high dance. “I don’t know. Nothing, I guess. Or something. It’s just that you’re Amber, you know.”

I didn’t know, I told him.

He placed his hands on my shoulders, putting distance between our bodies as he looked me in the eye and explained. “You’re Win’s daughter. Betty’s granddaughter. You’re smart and beautiful, and you’ve done so much more than I have. You’ve been to Mexico, learned another language. And I just don’t think I can do this. I can’t ask you out, because I’m afraid I’ll fuck …” He censored himself. “I know myself. I’ll mess it up.”

I was flattered, but as Blake explained how he held me up on a pedestal, I shook my head no. “What do you mean I’ve done more than you have? You’re in the Army—because you believe in it. Not because you want your college paid for, but because you believe you can do some good. You put off going to college for that. Don’t you think that’s something?”

He shrugged while I continued to shake my head. “And anyway, you’ll fuck it up by not trying, too.” I laced my fingers in his and pulled his hands together at the small of my back. “You have to try. We have to. Because I can’t stand it anymore. I need to know what this is.”

Finally, with a shy, closed-mouth kiss, he agreed.

Three years later, after abandoning the challenge of chasing after Blake for a new challenge—teaching English as a Second Language in Mexico—I sat on the tile floor of my Guadalajara apartment, coiling a phone cord around my finger as I waited for my dad to explain the reason for his call. I knew it was important, because I always called home. Mom always grumbled about her confusion over international prefixes and the cost of international phone calls, and Dad didn’t even seem to know it was possible to call out of the country, so something significant had to have happened.

I’d seen Blake each time I visited home, felt the pull of his body as we cruised country roads in his brother’s truck, listening to our playlist of “Midnight Train to Georgia,” “Piano Man,” and “Tracks of my Tears,” felt the brush of his thigh against mine as he sang “Desperado,” but I’d kept any lingering attraction I had to him, any lingering hope of a relationship, from moving to Mexico with me. I thought I had moved on. But when my dad’s voice rumbled, “Blake’s going to Iraq, I thought you’d want to know,” my vision crossed, blood rushed through my veins, my eardrums throbbed, and I found myself reeling back toward Blake like a tape measure curling back into its casing. I pictured his wide grin, his uneven penmanship on the back of postcards, the childish picture of a deer and evergreens he’d sketched to fill up one page of stationary. I remembered his profile against a frosted truck window, the glance of his eyes towards me as he said, “It would be nice to have someone to write to while I’m gone.” I was supposed to be there when this happened, I thought. I was supposed to give him something to come home to.

When I called Blake, though, he didn’t seem to need me. I could picture him, in his worn grey t-shirt, baggy carpenter jeans, hair tousled and sleepy expression when he came to the phone. I told him how I’d learned about his deployment, how I felt I really needed to talk to him before he left, how worried I was. I expected his response to be slow, weighted with regret.

�� Instead, he chirped dismissively, “Oh, yeah. We head to Fort Sill in a couple of weeks.”

“Wow, Blake. I’m sorry.” I paced as far as my phone cord would allow, wishing I could explain how much he still meant to me, how much it still mattered to me that he return safely, how I would probably abandon my boyfriend of 2 years and my job in Mexico to return to Bryant, South Dakota if he needed something to come home to.

“No, don’t be sorry,” he laughed. “This is what I’m supposed to do. This is why I joined the Army. You shouldn’t worry about it at all.” I remembered our New Year’s conversation, his reasons for joining the military. Apparently I still didn’t understand, because the duty that seemed like a burden, a tragedy to me, a reason to call and console was expected, welcomed even, by Blake. “It’s really nothing to be sorry about,” he told me. Blake’s confidence, his willingness to change the subject and find out what I was up to in Mexico, was reassuring, but it was disappointing to know that the identity I had imagined for myself—his something-to-come-home-to—had been my own construction. He really didn’t need me at all.

“Okay, well, good luck,” I said at the end of our call. It seemed like the wrong thing to say, so I tried again. “Take care of yourself.”

“Yeah, you, too,” Blake said. “And, hey, thanks for calling. Really.”

When I moved back to South Dakota on Memorial Day weekend of 2004, I didn’t think the return had anything to do with Blake. I thought our story was written in the past tense. But I remembered the recurring events of that narrative—the amateur baseball games on Wednesdays and Sundays, the Old Mil light, the slow drives over gravel roads—and during that first week home, found myself walking through the dark toward the baseball field. I knew the game would be over, but the players would still be there, scattered around the dugout and on coolers along the third baseline.

I was two blocks away when I heard Blake laugh. It was a drunken laugh, a series of loud staccatos that stopped me in the middle of the street. My pulse quickened, and I froze. I knew that if I didn’t turn around, didn’t walk back to my parents’ house on Main Street, I’d be walking toward Blake.

When I stepped into the dugout, gravel slipped beneath my feet, and several players turned toward the sound. Conversations paused, open mouths hovered on the lips of cans, as people squinted to make out a new face in the dark. I recognized Blake’s slender frame, his dangling-armed posture, even in the shadows, and exhaled relief as he responded, jumping up from the worn, green bench. “Amber? Is that you? What are you doing here? I didn’t know you were home.” He rushed towards me.

“Just moved back this weekend,” I said. “So, yeah, I’m home.” I hesitated, glancing at my feet, and was surprised when suddenly Blake’s arms were around me. It was an awkward, firm hug that trapped my arms at my sides.

Blake left his arms around me as he pulled back and asked, “For good? You mean you’re staying?” I slid my hands up to the small of Blake’s back and leaned back until my stomach pressed into his hips and our eyes met. As I tilted my head, but before I could stutter an answer, a red-headed kid lifted his baseball cap, scratching his head and walking toward us as he said, “Jensen, who’s the girl? You act like she’s the love of your life or something.”

“It’s Amber,” Blake said, grinning, still looking me in the eye, holding me there, tightly, in his arm. “I can’t believe you’re here.” He shook his head. “We beat Castlewood tonight—and we never beat Castlewood—and now you’re here. What are the odds?”

Blake turned, one hand cupping my elbow, the other reaching into a cooler beside him. He shook droplets of water off a silver can and led me to a bench in the dugout where we assumed our familiar positions—bodies turned into one another, knees brushing, my head titled down so that I peered up at him as I talked. We returned to our comfortable conversations—baseball and hunting stories I’d heard twenty times before—and our habit of retreating from the rest of the crowd as the night went on. Soon Blake was confessing to me how he had spent the last several years figuring himself out.

“I used to worry about stuff, about not doing things right. In college, I couldn’t even pick up the phone to order a pizza, sometimes, so you can imagine why I couldn’t call you.”

“I had no idea,” I said. “I mean, I just thought you were shy. I had no idea.”

“It’s okay, really.” We had turned so that we were side by side, but I was conscious of Blake’s t-shirt against my bare shoulder, his knee brushing my thigh. He twisted his neck to look me in the eye as he continued, “Because I’ve kind of figured myself out. First I went to a doctor, he gave me some kind of pills, and I took them for a while. But then I realized, I just didn’t feel like myself. I told myself, ‘You can’t let this ruin your life.’”

“Blake, that’s really amazing,” I said. I shifted uncomfortably, scooting slightly away as I placed my hand on the bench between us. But as I placed my weight on my hands, shoulders raising, I made sure the skin of our arms still met. “You know, I’m supposed to be getting married, Ernesto’s finishing his school in Mexico, he’s supposed to be moving to South Dakota next year.”

Blake didn’t hesitate. “If that makes you happy, that’s great,” he said. “It really is. I’ve met Ernesto, he’s a great guy. But I don’t see a ring on your finger, and you’re not married yet. All I’m asking for is a chance. So, my cousin’s getting married this weekend, and then I leave for two weeks of Army summer camp. Will you come with me to the wedding?”

By the time he asked the question, the edges of our bodies had been stitched up again—a tight seam from shoulder to knee. I answered, “We’ll see.” Within a few weeks, I was on the phone with Ernesto, explaining that my plans had changed. Within six months, Blake and I were picking out baby names and planning our wedding.

The whole story—of how Blake had become my soldier—passed through my mind as I stood at the patio door, watching for his return. He’d only gone to the gas station, had gone for cinnamon to satisfy my urgent craving, but as I waited for him to return, I imagined the urgency I would feel over the next year of my life: after Blake and I were finally married, after our baby was finally born, when I would be waiting for Blake to return from war.

I marveled at how Blake’s activation had caught me off guard. The significant events and dates alone should have been enough to prepare me for my future as a military wife—Basic Training and AIT, the 4th of July, Blake’s first activation, our reunion on one Memorial Day weekend and the wedding we were planning for the next—but I’d been swept up in the dramatic change, the romance-novel narrative of it all. It seemed our roles had reversed, like Blake had become my something-to-come-home-to, like I had moved home to my happily-ever-after. So by the time we found out we were having a baby, by the time we began planning our wedding, I’d stopped thinking of Blake as my soldier and begun reconceiving him as my husband, the father of my unborn child. And then Blake called with the news of his activation. His already deep voice rumbled like low static on an AM radio station when he said, “Amber, my unit’s being activated.”

“Your what? What does that mean exactly?” I waited for his response as the heat of my cell phone melted a flesh-colored film of makeup onto to its own plastic face.

“It means I’m going to Iraq.”

It was all so still new—the wedding plans and the baby names—that I had given myself permission to forget about the possibility of war until that moment, until Blake began apologizing for calling, not telling me face to face, for needing to get it off his chest, needing to just say it. I’d never really considered what it meant to be a military wife, not until that moment, when I found myself at the intersection of expected and unexpected, experiencing the word activated—really feeling it in my gut—and tasting the word Iraq. I realized that although I had known Blake essentially all my life, I was just learning to depend on the sound of his breathing to ease me into sleep at night, the slight weight of his hand on my bulging belly, to appreciate the fact that he would walk through snow for a few simple ingredients. I realized that soon he would be leaving and I wouldn’t know when he was coming back.

From my perch at the patio door, I spotted Blake’s lean body angling into wind-slung snow, his bare hand clutching a paper sack as he returned from the store. I blinked at the sight of him, then hurried to the kitchen and busied myself with the melting of butter and packing of brown sugar. I heard the security door rattle downstairs, and soon he was inside, smoothing his wet hair, handing me a little brown bag, inside a tiny red and white labeled shaker that probably cost four dollars at convenience store prices. I stopped him before he made his way back to the couch and kissed his full, smiling cheek.

Before the end of the night, Blake returned to the same store two more times—once for brown sugar, once more for ice cream. When he made those trips, I stayed in the kitchen, mixing ingredients, wiping counters, and washing dishes. I didn’t want to watch him leave. Finally, after all his work, I settled in on the couch next to him, a warm bowl cradled in my hands, one craving satisfied, at least temporarily.

AMBER JENSEN is an instructor at South Dakota State University, where she also coordinates the Veteran’s Writing Workshop. Now ten years past 27, she is blessed with a family that she adores and work that inspires her.

#amber jensen#south dakota#iraq#mexico#creative nonfiction#essay#essays#writing#writers#literature#lit#litmags#zines#27#iamtwentyseven

2 notes

·

View notes

Audio

I was a biter.

It felt good to take someone’s

flesh between my teeth.

And they’d come running,

pry me off, but the marks stuck:

little O of dents,

Stonehenge from a plane,

something ancient and holy,

sacrifical site.

They said I was bad.

I played along, feigned sadness,

but knew they were wrong.

We make others ours

when we grip them tight, taste fear

while we’re in control—

blood astonishments

mingled with their drier skin,

then I’d let them go.

*

Desire didn’t leave.

I’m no longer a biter,

it’s true, but still love

the taste of bodies

I love. I bit my school friends

because they would stay

and I could see what

I’d become in their eyes—see

pain so close to me.

Now biting is shared

with my lover, and takes us

out into the wilds

where the grass and moon

can get at our skin. We play

at the ragged edge

of desire, where the

animals hidden in us

roam the fields again.

DAVID ALLEN SULLIVAN has published, Strong-Armed Angels, three of its poems were read by Garrison Keillor on The Writer’s Almanac, Every Seed of the Pomegranate, a multi-voiced manuscript about the war in Iraq, and a book of translations from the Arabic of Iraqi Adnan Al-Sayegh, Bombs Have Not Breakfasted Yet. Black Ice is forthcoming from Turning Point. He teaches at Cabrillo College, where he edits the Porter Gulch Review with his students, and lives in Santa Cruz, California.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Search Warrant

I need to be married by age twenty-seven so I can have two kids, a boy and a girl, three years apart by the time I’m thirty-one. That way I’ll be mid-fifties when the last one graduates from college and my husband and I can start traveling.

I was almost engaged last summer to a six-foot-ex-Marine with a black cross tattooed on his bicep. For two months we raced his candy-apple-red Harley over country back roads and I thought we were really going somewhere. But then I learned that he voted right. Worse, he was Catholic.

Then I met Kurt at Jennifer’s wedding reception. After three plastic glasses of white wine apiece, we scooted our folding chairs close and dragged out our bios. Both lapsed Methodists. Both Gemini. That was enough to raise hope, so we rented a room with a jacuzzi and electric fireplace right there in the hotel. The sex was great, but between rounds, he sneaked into the bathroom with a copy of Wild Wet Girls on the Beach that he picked up in the hotel gift shop. Plus he sprayed toothpaste and dropped wet towels, so as soon as I got home Sunday night I texted goodbye.

My sister Eileen says I’m too picky. But who’s she to talk? At twenty-three she’s already been through a double-wide divorce from some guy who gave her two girls under age three and a bad case of herpes. Now she’s dating a guy she met bowling, who she says hardly ever uses drugs, just mostly at parties. I love her, but she invents disaster every day, and that’s not for me. I’ve got plans.

So next time I reel back to fish my own pond—Martin, a claims adjuster like me, eight-months-divorced, works in the next cubicle, nice voice on the phone. First date he shows up with white roses from his garden, so sweet. But after red dragon martinis and sea bass, he opens his wallet and shows me a photo of twin seven-year-old boys. “Both ADHD,” he sighs, rubbing his cheeks. “I get them alternate weeks.”

Maybe I am picky like Eileen says, but I’ve seen too many mistakes. Besides Eileen’s mess, my other sister Lexie came home early from zumba and found her husband Brad on the concrete floor of the garage with her neighbor’s husband. And my best friend Patty’s six-month-boyfriend packed his bags and her new laptop computer while she was at work and disappeared. She got a postcard of a polar bear cub from Toledo, but wasn’t sure if that was his final destination.

Then Patty hooks up with a new guy online, says I should try it, shortcut through the losers, let technology vet. After only ten dates, they’re planning an expensive surfing vacation in Costa Rica, so you know that’s going great.

Nothing to lose, right? My mind sees a cyber split screen—me on one side and a parade of good-looking guys on the other, each lasting until he picks a wrong answer and—whoosh—he’s whipped into cyberspace. No breakup, no tears, no lost time. Then after the losers are gone, the system freeze-frames my perfect match, like a CSI fingerprint search.

After a couple of weeks, I’m ready to meet my perfect match, Seth Anderbo, but just to be safe I arrive at Starbucks twenty minutes ahead so I can spot him and escape if I need to. He walks in five minutes later, wearing the aqua Hawaiian shirt he promised. I like punctual, so I’m impressed.

He orders skinny lattes, leans in, and grins, “You hate smoking, you’re not religious, you vote left, and you’d rather contribute to a food pantry than a political party. Am I right?” He nods, grins again, “I work with computers and they don’t make mistakes.”

Good. I’m too old for mistakes.

By 2:30 we’re locked in laser eye contact and speed-flipping up matching cards—we both love Damages, Petoskey stones, and the Traverse City Film Festival. Hate cilantro, hominy, Fox News, and the grit in morels. It’s like I’ve stepped into a mirror. This guy is perfect. Let’s go.

When I get back to the table, he stands and grabs my arm, “Let’s walk to my place, order a pizza, watch a movie.”

I’m in, but the sky’s black and it’s pouring rain. Can’t he see that? I say, “Great idea, but let’s take a taxi.”

He tightens his mouth, “But you said you like long walks, and this is only a mile.”

Trying to laugh, I admit, “Well, yes, I told the truth, but I don’t like battling hard rain in forty degrees.”

He’s smiling again, but like I’m mistaken and somewhat of a sissy. “Just a light sprinkle,” he insists, stepping away from the table and snapping a big black umbrella over my head. He’s still smiling, but his teeth disappeared, “And my phone says it’s 47 degrees.”

Doesn’t he know it’s bad luck to open an umbrella inside? My feet won’t move, and I notice a stain on his shirt, point it out.

He licks his thumb, daubs at the spot, “Nope, not a spot, just part of the pattern.”

“Don’t think so. It’s brown.”

He pinches the cloth, holds it toward me. “Nope. See? Not brown. Just part of the pattern.”

My molars clamp. “No, it’s definitely a spot. See? The color around it is lighter.”

His smile slips and he bites his upper lip, stares at the umbrella handle. “You can’t admit that you’re wrong?”

“I can, but I’m not,” I insist. “You are.”

“You’re stubborn,” he frowns.

“So are you,” I shoot back.

Well.

He distracts toward the window, nodding, lips pursed, jerking his free thumb straight up. “See? I was right. Rain’s stopping. Storm’s breaking up.”

I duck out from under his umbrella, grab my purse, head for the door.

Next Monday I’ll be twenty-seven.

TRUDY GORDON CARPENTER has published over a dozen pieces of fiction that range in style from Bambi to Deliverance. She has been nominated for a Pushcart twice and is crafting a collection of her short stories. She lives in a small green house on the rocky shore of Lake Michigan.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mod Weary

“You done too much, much too young.” —The Specials

“You stopped dancing.” —The Who

It was a mod dance in San Francisco, the fall of 1986. Every face at the club was wearing suits—which made me feel like hell. I was wearing white (well, by then, dusty grey) Levi’s and a black turtle neck under a white Fred Perry vest. My socks were navy blue errors around my ankles—I’d thought they were black socks when I pulled them on in the dim light of somebody’s city apartment, and kept thinking it until I saw them extended out from under a club table an hour ago—ending in my loafers.

I felt shabby and worn; I’d slept in these clothes on a couch that had hurt my neck and left me feeling all balled up and tight inside instead of like I’d slept. I ached everywhere.

I had four cigarettes left.

Music started.

I lit one.

Three left.

The latest mod girl I’d arrived with, Joy, bounded over. She was cute, but I’d begun to feel old when I went anywhere with her. She had to be at least 21, but even with make-up and mod dresses, she looked 15. She cashed in on it, too. She came up to my mid-ribs with soft blonde bobbed hair and china doll blue eyes that went round like a little girl’s when she was pleased. Half the faces I knew were in love with her.

She’d slept on that couch, too, but she’d woken fresh and charming—her mini-dress, albeit, was a tad rumpled about the collar and sleeve, but she somehow managed to look appealing in it, while I just felt grubby. Out of step. Even my parka, which I hadn’t slept in, was wrinkled—and there were two cigarette burns on the front right hand pocket that I had no idea how I’d gotten. I wanted to go home.

Joy dragged up a seat close to me and slung her feet on the rung of my chair. She’d been drinking.

“Isn’t this wonderful? Did you see all the mirrors? The Sorts are going to play another set. I can’t believe that Lewis is here with another girl and that Tina is pretending she doesn’t care. Can I have a cigarette?”

She didn’t actually ask that, she said it as a preamble to taking one, and, stopping to light it with another fellow’s proffered lighter as he passed between the tables, she continued on with her chatter.

I watched her eyes snap and move about the club, taking it all in. Drinking it. Breathing it. Seeing who was here. Who was wearing what. Who was with whom.

I felt really old. I was 27. Too many mates of mine had moved on, selling their three button suits to the faces wearing them now. The French-crew style cut I sported was on the way out and the bands were doing covers of the Specials. I felt robbed of something. I felt like some prehistoric thing who’d wandered into the wrong place and was left there to sit.

My cigarette was dragged out.

I had two left.

I slipped my cigarette case—brass plated and monogrammed, now slightly tarnished and dented from when I’d crashed my first Vespa, but still an ace—into the pocket of my parka as it lay heaped on the chair beside the table.

I wondered how long I could last with only two cigarettes.

J H HOBSON has been 27 for a few years now, with a body of work lurking in odd corners of the internet and old bookstores.

3 notes

·

View notes

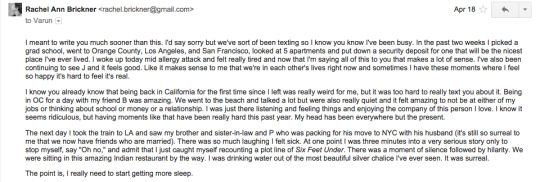

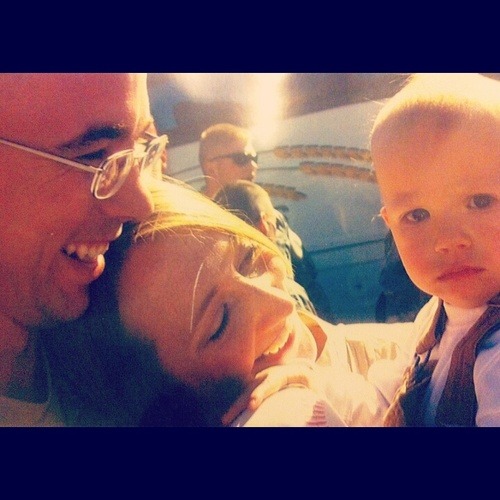

Photo

Twenty-seven was a teething, chewing sensation. Itchy, dissatisfied, hungry. It found me trying my damnedest to unbury myself from a paralyzing pile of good habits. My pictures had gotten really, really dull, probably in the name of professionalism. I wanted my eyes back. Adopting a new disregard for The Rules was a private, deliberate exercise, kinda like going commando. The new guidebook said, Alllllright, Hryciw: Daytime is for work, where we uphold the grand parade of meticulous habits, fuss over sixteenths of a stop, and judge sharpness magnified at 200 percent. After hours, though...that's when we let things go soft and dark, shoot with fluorescent bulbs and lampshades, don't sell a thing, don't second guess. Don't stop until something cool has happened. Anything can be a light source, not just a big white box. Anywhere can be a studio, not just a big black hole. Stolen freedom spilled over and seeped into the cracks. There was lot of staying out and getting sweaty. Howling at the moon. Listening to voices. Coming home to my batcave, standing at the open fridge door and eating with my fingers. If I should get the notion/ to jump into the ocean/ 'tain't nobody's business if I do. Kicking and flailing can't last forever, of course. The humblers were in the mail, poised and ready with a stinging slap to remind me that I didn't know shit. But that was another year.

HEATHER HRYCIW is a freelance photographer living in Oakland, California. Her eyes enjoy many activities such as blinking, peeping, teaming up on jobs, studying telephone pole flyers, pretending to have x-ray capability, and decorating her vacation home at hchphoto.tumblr.com.

#heather hryciw#photographs#photography#writing#writers#literature#lit#art#litmags#zines#27#iamtwentyseven

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the Spirit Of

I drove directly from San Francisco International Airport to San Jose, not stopping to admire any bridges, beaches or embarcaderos. My destination was the Sarah Winchester house, an architectural monument to the aftermath of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and the possible insanity of its designer, Sarah Winchester. The well-kept Victorian exterior barely masks the labyrinthine interior: doors lead to nowhere, windows are built into ceilings, stairs switchback three or four times then end in solid brick, a priceless Tiffany stained-glass window is inset on an interior and north-facing wall.

Sarah Winchester built her house almost nonstop, 24 hours a day, seven days a week, for nearly 40 years. According to lore, her motivation was fear, compounded by the death of her husband, the treasurer of the Winchester Repeating Arms Company, and the more distant loss of her only child, a daughter. When a Boston medium told a distressed and wealthy Sarah Winchester to start building a house for those who had been killed by the Winchester rifle, she complied. According to the medium, halting construction for any reason portended Sarah’s certain and immediate death. Sarah bought a small farmhouse with several acres of land and eventually expanded it into a 160 room Victorian maze.

My discovery of Sarah Winchester’s house in a library book at age 11 coincided with my newfound belief that my house was haunted. The closet of my childhood bedroom in a non-descript ranch-style house contained a door to an attic crawlspace. When the air conditioning was on, the garbage bag covering the crawl space door moved. Logical explanations aside, I convinced myself that something supernatural was living in the attic. Eventually, I came to believe that the entire house was haunted. I refused to be in the basement in the dark. I thought I spotted the ghost of Abraham Lincoln in our laundry room once. When my parents announced that they were building a new house about 500 feet down the road from our current house, I was relieved to move to a place that was decidedly unhaunted.

It took two years for my parents to design and build the house, which felt like 40 years to me. I crawled into bed at night with my mother and watched her use graph paper to lay out her dream house: a room for each of her four girls, an in-law suite in the basement, a study with custom art-deco doors. My mother drew each room to scale, sometimes falling asleep with a graphite pencil and a ruler in her hands. I’d remove the paper from her fingers, gently, and trace my fingers over the pencil lines and eraser marks. It looked like home.

When the foundation was freshly poured, my parents, sisters, and I pressed our palms into the tacky, grainy cement. As soon as I lifted my hands, I realized we had made a grave mistake: our handprints would make the foundation crooked. My parents laughed off my concern.

“It’ll take more than that to ruin this house,” my mother whispered confidently as she cleaned my hand with a damp baby wipe.

Once we moved in, my mother never stopped trying to make the house feel like home. She custom painted the foyer to make a wall look like marble, purchased new art and draperies, and nagged my sisters and me into routinely dusting the baseboards. Still, the house was too big to maintain and the credit card balances were too high to pay. Years after we moved into our not-so-new house, occasionally I’d hear my mother crying in the enormous walk-in closet she designed on graph paper and willed into existence. Sometimes I’d go sleep in another room to escape the noise, trading my vaulted ceilings and queen-sized bed for my sister’s twin mattress in a bubble-gum pink room. Other times I laid in bed quietly, hoping the noise would stop.

Supposedly, Sarah Winchester never slept in the same room twice in fear that the spirits she was running from would find her. On the tour, we walked through a succession of empty bedrooms and I wondered how she kept track of which rooms she had slept in, which rooms she hadn’t, and which rooms the ghosts had found. I opted into the behind-the-scenes tour, which culminated by leading us to the basement where we donned hard hats, grabbed flashlights, laughed awkwardly, and promised that we wouldn’t separate ourselves from the group.

“There are no blueprints for the house or for the basement. If we lose you down here, we can’t guarantee we’ll find you again,” the tour guide smiled through the warning.

When I was 18 and on week-long break from college, my father came into my bedroom while I was reading for literature class and told me that he and my mother were separating and our house was for sale. Soon the tours of prospective buyers started: most hated the wallpaper my mother had spent hours agonizing over, many wanted to paint over a lemon-yellow bedroom, a few stopped to appreciate the wood-paneled study. My mother’s projects were left half-finished and she stopped asking us to dust.

When Sarah died of natural causes, the construction finally stopped. Her belongings were auctioned off by a niece, the home left twisted, empty, and misunderstood. Eventually it was reclaimed and restored as a roadside spectacle for tourists on their way to the Golden Gate Bridge or Google. I spent an hour and a half walking through the building and the grounds of Sarah Winchester’s house, but there are still 50 rooms that I didn’t see and probably never will.

I have seen enough, before and after my trip to Sarah Winchester’s, to know that sometimes houses come to embody the dreams and fears of those who build them, no supernatural interference is required. There’s a theory that people who are still living can leave behind their energy in a space, effectively haunting one location while being very much alive in another. In the years since we’ve been out of the last house we inhabited as a family, I’ve come to wonder if we haunt it. Maybe the new owners made up stories about us based on the murals and paint we left behind. Maybe someone hears my mother crying in the walk-in closet or moves from room to room trying to escape our voices. Maybe it is haunted by something long dead and hidden in the soil that we disturbed, something truly supernatural.

All of the pictures I took the day I visited Sarah Winchester’s house are external, taken from the well-manicured gardens in front of the house. In a few pictures, there’s a gray figure in front of the window in the top center of the house, perhaps a trick of the light or a misleading shadow. But as the daughter of a woman who possibly built a haunted house, let me speculate: maybe it’s Sarah Winchester, maybe it’s her daughter or niece, maybe it’s a victim of the Winchester rifle, maybe it’s me 16 years before I was 27, making the journey to California in spirit from my mother’s warm bed in Pittsburgh, graph paper in hand. Or maybe it’s nothing at all.

SAMANTHA GOLDSTEIN was recently disappointed to find out that Abraham Lincoln has no connection to her childhood home in Pittsburgh, PA so it was probably not his ghost in the laundry room. She administratively advises PhD students in engineering and is always up for a good ghost story.

#samantha goldstein#san jose#pittsburgh#essay#essays#writing#writers#literature#lit#litmags#zines#27#iamtwentyseven

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

One Major League Ending, One Seriously Notable Beginning

Now that I’m an entry-level old person, I think about what I’m going to do in however many more years I’ll get. That number’s a secret but still I make plans – ironically, hopefully, whatever. One of those plans is for my next book. Right now it’s looking like a hybrid genre, a fat mixtape of memoir and other things TBD. The seeds of this book were planted the year I turned twenty-seven. In that year, 1970, I lived through one major league ending and one seriously notable beginning.