#william redfield

Text

Do you like Hamlet? John Gielgud? Richard Burton? Theatre and film history? The process of putting on a show? Snarky, insightful, really entertaining commentary on all of the above? Then you're in the right place! Emails from an Actor is a (mostly) real-time readalong of John Gielgud Directs Richard Burton in Hamlet: A Journal of Rehearsals and Letters from an Actor, two books written about the 1964 Broadway production of Hamlet. Both have been out of print for decades, but I acquired PDFs, extracted the text, edited it, and now they exist in accessible form, woohoo! (Edit: Letters from an Actor is coming into print again on March 5! I'm still going ahead with the emails, but buy it when it's out!)

John Gielgud Directs Richard Burton in Hamlet: A Journal of Rehearsals by Richard L. Sterne, is, well, what it says on the tin! Sterne, who played the Gentleman and understudied Laertes, secretly tape recorded rehearsals, going so far as to hide under a platform for a private rehearsal with just Gielgud and Burton. The book summarizes and quotes heavily from those recordings. It also includes a prompt-script for the production with descriptions of the blocking and acting choices - I haven't edited that part yet, but I plan to.

Letters from an Actor by William Redfield, who played Guildenstern, is less objective but way more fun. I love it so much that when I first got it in 2006, I just about killed my hands typing up quotes to share on Livejournal. Redfield had an extensive career in theatre, film, and TV. He's best known for playing Dale Harding in the film One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, but if you happen to be a musical nerd, you might know him as Mercury in Cole Porter's Out of This World. (Also relevant to musical nerds: Alfred Drake as Claudius, John Cullum as Laertes, and George Rose as the Gravedigger!) The book is structured as letters to a friend, Robert Mills, who wanted to know about life in the theatre. Redfield took Mills from his audition through opening night on Broadway, relating thoughts and anecdotes about his profession along the way. As in Hamlet, Richard Burton plays a major role, with stories of his own and a glimpse into his life with Elizabeth Taylor in the days surrounding their (first) wedding. The rehearsal process was frustrating for Redfield, and with all the time he and his Rosencrantz spend feeling lost, the book kind of comes across as a Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead AU.

I'll be sending out the journal entries and letters on the days they were written and/or are about, with just a little bit of jumping around in time. Subscribe here! I made it private for copyright reasons, but don't worry, I'll approve everyone. The emails will start with some introductory material on January 24 and continue through an epilogue in mid-April. Follow this blog for some extras! And reblogs, if people end up talking about this! Tag me or use the tag "emails from an actor" if you want me to see something.

I'm so excited to share these books with people! But mostly Letters from an Actor. Seriously, it's so good.

#hamlet#shakespeare#john gielgud#richard burton#elizabeth taylor#william redfield#is the guy in the icon by the way#rosencrantz and guildenstern are dead#(not really but i think people who like it will also like this so hey!)#emails from an actor

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

Every time Burton shares an entertaining anecdote about Olivier, he emerges as an unreliable narrator. And Redfield consistently proves to be a meticulous fact-checker. It raises suspicion that Burton might have fabricated some of his other stories about his colleagues. They are still great and amusing even if they are not true.

In "The Motive and the Cue," they incorporated an episode where Burton recounts a tale of Olivier supposedly severing his hand in "Titus Andronicus." However, all the Redfield’s incriminating observations are attributed to Gielgud, who reveals them only when he and Burton are alone. This allows him to expose Burton without undermining his credibility in his colleagues’ eyes:

The reason why you can’t remember the speech is because it isn’t there. Titus doesn’t even chop his own hand, Aaron the Moor does it. […] So I don’t know which speech of Sir Laurence Olivier’s you are remembering, but it was not that one.

#emails from an actor#the motive and the cue#laurence olivier#john gielgud#richard burton#william redfield

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Richard Burton said of his reading, “I have banged along so quickly because I am so nervous. In the recent production with Peter O’Toole at the Old Vic, they played the full four-hour text. Since there are no cabs outside the Vic in the late evening, a Londoner without a private car has to catch the 11:20 underground or he’ll spend the night with friends. According to O’Toole, the final scenes were played not in terms of Shakespeare but the subway. Actors simply used their lines to plead with the audience to remain. ‘Good night, sweet Prince’ was not a farewell to dying Hamlet but a sad good-by to departing patrons. As for Fortinbras, the people who saw the O’Toole production wouldn’t know him from the Second Gravedigger.”

— Letters from an Actor, William Redfield. Richard Burton on the troubles of shows with long run-times.

#Letters From An Actor#William Redfield#Richard Burton#Hamlet#theater#Emails From An Actor#quotes#words#this made me HOWL#The mental image of them mournfully watching the patrons rush out...#I imagine the Les Mis casts throughout the years experienced this a lot too.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

#one flew over the cuckoo's nest#Jack Nicholson#Miloš Forman#Ken Kesey#Jack Nitzsche#Louise Fletcher#Will Sampson#William Redfield#Brad Dourif#Danny DeVito#1975#70s

11 notes

·

View notes

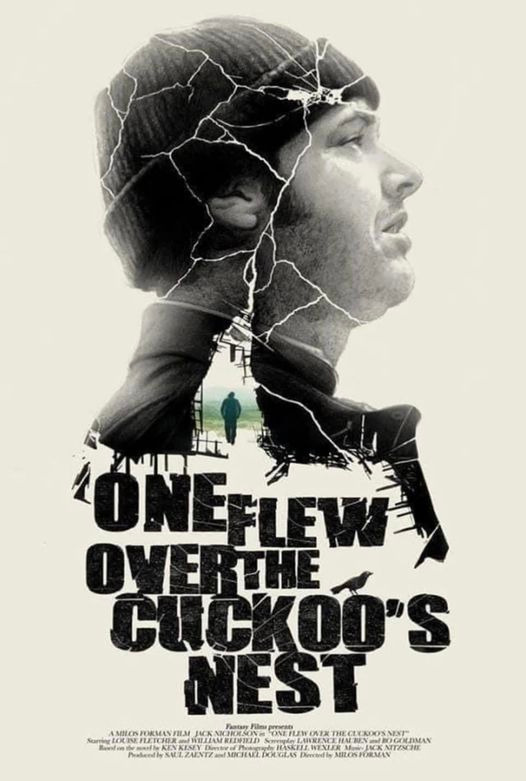

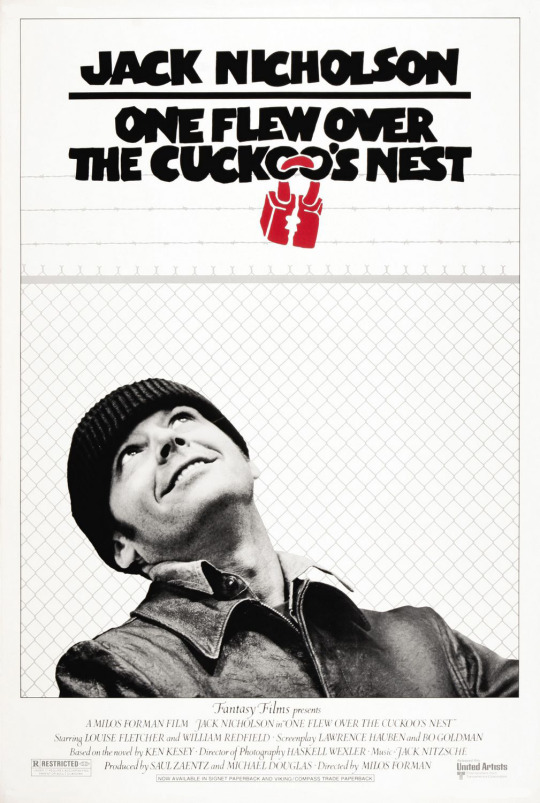

Photo

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975)

This is a Movie Health Community evaluation. It is intended to inform people of potential health hazards in movies and does not reflect the quality of the film itself. The information presented here has not been reviewed by any medical professionals.

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest has one scene where a light switch is flicked on and off several times to get the attention of the room, lasting about 30 seconds with the flashing being very mild.

A few intense scenes are filmed with handheld cameras with mild shaking. One sequence takes place on a boat that rocks naturally and turns in circles briefly. These parts of the movie take up a small amount of runtime, and the rest of the camera work is either stationary or very smooth.

Flashing Lights: 2/10. Motion Sickness: 2/10.

TRIGGER WARNING: The overall tone of indifference to the wellbeing of people with mental illness is likely to be upsetting. Stories are told of subjects that include statutory rape and suicide. Electroconvulsive therapy is depicted viscerally, with one character having an intense panic attack before being subjected to it. The aftermath of a death by suicide and of a lobotomy are shown. There are moments of cultural insensitivity against a Native American character.

Image ID: A promotional poster for One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest

#Movie Health Community#Health Warning#Actually Epileptic#Photosensitive Epilepsy#Seizures#Migraines#Motion Sickness#United Artists#One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest#November#1975#Jack Nicholson#Louise Fletcher#William Redfield#Miloš Forman#Rated R

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

#death wish#action#drama#movies#1974#1970s#charles bronson#william redfield#hope lange#michael winner#movie posters

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Connection (Shirley Clarke, 1961).

#the connection#the connection (1961)#shirley clarke#william redfield#arthur j. ornitz#richard sylbert#albert brenner#ruth morley

47 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#fantastic voyage#stephen boyd#raquel welch#edmond o'brien#arthur kennedy#donald pleasence#arthur o'connell#william redfield#richard fleischer#1966

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#charles bronson#michael winner#death wish#1970s#poster#movie posters#vincent gardenia#william redfield#movies#post#movie poster

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

You know a characther is fucked up and traumatized when they are wearing one of these

#ellie williams#rose winters#chris redfield#travis bickle#andrew garfield peter parker#james sunderland#and many more#i think#there's probably more#the last of us#resident evil#taxi driver#spiderman#silent hill#charlie kelly#ethan winters#john rambo#jesse pinkman#luke danes#lance mcclain#pete maverick mitchell#komaeda nagito#peter b parker#betty grof#dean winchester#leo valdez

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

Yesterday's Movies commits to One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Fantasy Films 1975.

View On WordPress

#70s#1975#Jack Nicholson#Louise Fletcher#Will Sampson#Brad Dourif#Danny DeVito#Christopher Lloyd#Scatman Crothers#William Redfield

1 note

·

View note

Text

Another excerpt from William Redfield's Letters from an Actor:

...but fate reserved a particularly horrendous booby trap for [Geoffrey] Toone in the production of Henry V. Whoever directed decided, somewhat academically, that it would be an interesting and decorative notion to dress Shakespeare’s fighting men in authentic 15th Century armor fashioned from iron. Mr. Toone was consulted in the matter, but, being a friendly and rather ingenuous young man, he agreed. It was also determined that young Harry’s “Imitate the action of the tiger” speech, in which he exhorts his troops to further battle, should be done straight front to the balcony rail—as though the audience itself were a troop of soldiers and Henry stood challengingly on a promontory before them. This naturally dictated that Mr. Toone’s Henry would be alone on stage when he began the speech.

On opening night, several actors endured almost insurmountable difficulties while trying to move about vigorously in their suits of armor. The rehearsals had been sketchy (as they often are at the Vic), and Toone himself had practiced in his armor only once. When he bounded onto the stage, all confidence, and began crying, “Once more unto the breach, dear friends, once more!” he realized that the armor was simply not going to cooperate with his agility. By the time he had completed his first pentameter, he fell down flat on the stage. Worse than that, he could not get up. The armor was simply too heavy. Having fallen on his back, he was turned Kafka-like into a helpless turtle or beetle or shell-backed what-you-will. Saddled with a burden of inhuman metal, he could do no more than wave his arms desperately and shout his battle cries from a supine position. The barely suppressed giggles of the audience made it clear to him fairly soon that any continuance of such an erect speech from such a prostrate position was positively grotesque. He paused for a moment but could do nothing but wave his arms again. He tried to move his feet but they lacked sufficient power. He gave a lurch with his body but the armor undid his efforts. He finally did something very brave indeed. He turned his head to the wings and shouted, “Help!”

Several supernumeraries appeared on the double and lifted their Prince to his feet. They appeared to be nothing so much as the derricks of Agincourt in human form. Once on balance again, Mr. Toone made certain to move neither his feet nor his hands too abruptly. Though he was bound and determined to avoid a second fall-down, he nevertheless conducted himself in such a robot-like fashion that he recalled nothing so much as the Tin Man in The Wizard of Oz. The laughter of the audience became gradually unrestrained. According to Richard Burton, Toone tells this tale on himself. Not only does this prove him ultimately courageous, we clearly see that he is blameless. Moreover, a man who swallows his pride sufficiently to shout for help when all else fails is a man with an obvious talent for survival.

Plenty more where that came from. :D Read it all with Emails from an Actor!

#henry v#shakespeare#geoffrey toone#he later played a doctor who villain among other things#william redfield#emails from an actor

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

Last month, "The Motive and the Cue" moved to the West End (originally staged at the National Theatre), symbolically finding a home at the Noël Coward Theatre, where John Gielgud played Hamlet back in 1934.

After less than two weeks of our read-along of "Emails from an Actor," I was so excited to see this play that I could hardly breathe when I saw "Day 1, The Play’s the Thing" projected on the black curtain! Honestly, this has been the best play I’ve seen in the last four or five months (and I go to the West End almost every week). The entire production revolves around the captivating power struggle between the legendary John Gielgud and the flamboyant Richard Burton, with Elizabeth Taylor acting as a calming force. Act one, aptly titled "The Motive," explodes with conflict, culminating in a public humiliation of Gielgud by Burton, and the second act, “The Cue,” focuses on the peace process and completes with reconciliation and a successful premiere. It’s rare to find an end of the play stronger and more cathartic than an end of the first act, but this play achieves it beautifully.

Johnny Flynn breathes life into Burton, portraying him as charismatic, expressive, and loud, yet hinting at hidden demons. However, I felt that he was trying too hard to mimic Burton's voice and mannerisms. Flynn's natural voice doesn't have the same level of hoarseness, so much of his performance feels more like an impersonation.

Tuppence Middleton steals the show as Taylor. Her captivating presence shines in every scene, offering a nuanced portrayal that deconstructs the stereotypical image of the airheaded Hollywood beauty. The connection she forms with Luke Norris' William Redfield, based on their shared childhood experiences as actors, is a delightful highlight. Redfield is arguably the most prominent supporting character, and his presence is impactful. But, unfortunately, there was no Sterne.

The real star and the absolute best part of it all was Mark Gatiss as John Gielgud. He is so natural in this role: knowledgeable, gentle, charismatic, witty, and extremely vulnerable. (By the end, you yearn to offer him a comforting hug.) This is exactly how I imagined Gielgud from what I’ve read so far in Redfield’s and Sterne’s texts. During the first rehearsals, Mark Gatiss even did something mentioned by Sterne: “he was also acting all the parts with the actors, mouthing the lines, reflecting the emotions in his facial expressions, and kinesthetically making all the gestures.” It was so lovely! And he did many things described by Redfield as part of Gielgud's ‘directing style.’ It was amusing to recognize quotes from both Redfield and Sterne throughout the whole play, even if repurposed for different situations.

The staging was both beautiful and smart. They used three locations: the big white rehearsal room, the smaller red hotel room (of Burton and Taylor), and the smallest blue room (of Gielgud). This last room was the most intimate space, where Redfield came for acting advice (and Gielgud told him that his advice cannot make him a better actor) and where Gielgud himself brought a sex worker boy ('I just wanted to do something reckless') – this is the most touching scene! I also liked the production’s attention to details: for example, when Taylor and Burton host a party in their room, we see vases with flowers – roses and tulips, and when we return to their room a few days later, we see these same flowers withered!

I really enjoyed the play. It was a captivating blend of wit, intelligence, and genuine tenderness. And it was nice to see our guys 'alive.' Gatiss/Gielgud is my big love! The whole experience made me very emotional.

The three rooms:

Our boy William (Luke Norris):

Mark Gatiss/John Gielgud:

#emails from an actor#the motive and the cue#mark gatiss#john gielgud#william redfield#luke norris#johnny flynn#tuppence middleton

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

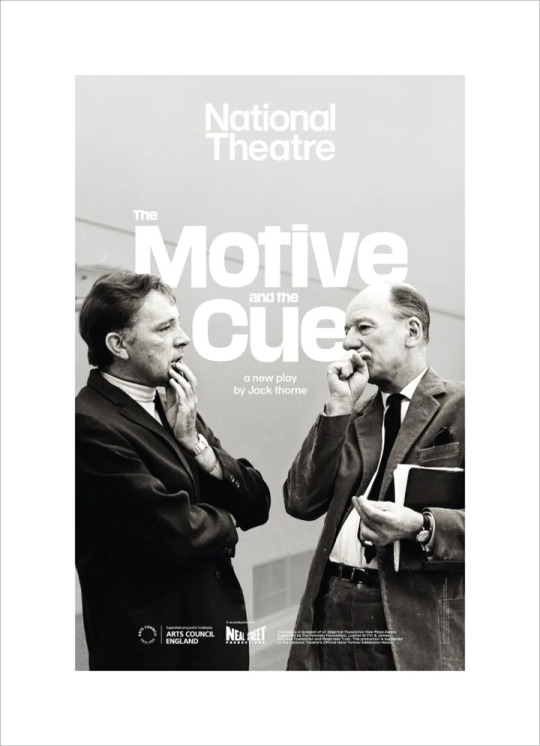

Gielgud, Burton, Hamlet and Taylor, too!

The clash of the titans: Gielgud and Burton. Theatre versus film. Art versus stardom. Classic versus modern. Veterans in their craft Gielgud and Burton try to reveal yet another side of Shakespeare's 'Hamlet' and show what they're made of.

Egoes and artistic differences start to dismantle the play before if fully becomes the play – at the rehearsals tension is tangible, to say the least, when the director (Gielgud) and the actor (Burton) don't see eye to eye when it comes to the version of 'Hamlet' they intend to produce.

Chaos expands with each day, devouring good intentions, bad tempers and even worse habits don't mix very well and the pile of wrongs threaten to bury everybody under it.

Fears and insecurities threaten to ruin the show, the vision and relationships. But it may be the fear and insecurity that will be its saving grace, where the friction becomes the edge and the edge produces the defining moment. The motive and the cue.

The company delivers an exceptional show (along with the deep dive into 'Hamlet', perhaps one you didn't know you needed, yet fascinatingly insightful). The chemistry between the actors is undeniable, Gatiss' Gielgud is awkward, seeping with knowledge about Shakespear and rigid about his vision, Flynn's Burton is changeable, unruly, larger than life, yet drowning in self-doubt star. You can't take eyes off of him, he's magnetic, mesmerising and every encounter with Gielgud provides sparks. Tuppence's Taylor might seem underperformed at first (even though there's no doubt that eyes of everyone gathered in the 'room' are indeed fixed on her as she hosts the parties for the company), but there is a very good reason why she's actually on the backseat of that ride. To paraphrase – she's happy to serve Richard for once and support him. She's a broker of peace, she's providing entertainment, she is his stimulus. But it's his time to shine.

Stage design is a beautiful, intricate clockwork: different 'rooms' appearing effortlessly within curtain's drop and raise. A paradox really, but classic and modern solutions working perfectly in sync together (machinery of stage design, décor, journal's entries projected on the black curtains).

Sam Mendes directs Mark Gatiss as Gielgud, Johnny Flynn as Burton and Tuppence Middleton as Taylor in this funny, brilliant, surprising play by Jack Thorne posing the question of art, stardom, revisiting classics and maybe even the essence of the theatre itself.

Inspired by 'Letters from an Actor' by William Redfield and 'John Gielgud Directs Richard Burton in Hamlet' by Richard L. Stern 'The Motive and the Cue' offers a look into rehearsals, an insight into the process and deep analysis of well known classic.

–

The Motive and The Cue.

Dir. Sam Mendes, play by Jack Thorne, cast includes: Mark Gatiss, Johnny Flynn, Tuppence Middleton.

In Lyttelton Theatre (National Theatre) until 15 July '23.

[photo: National Theatre]

#the motive and the cue#sam mendes#jack thorne#national theatre#play#theatre play#theatre#mark gatiss#johnny flynn#tuppence middleton#john gielgud#richard burton#elisabeth taylor#hamlet#shakespeare#william shakespeare#play review#letters from an actor#william redfield#john gielgud directs richard burton in hamlet#richard l. stern

1 note

·

View note

Text

#resident evil#william birkin#william birkin x reader#albert wesker#albert wesker smut#albert wesker x reader#billy coen smut#carlos oliveria smut#chris redfield smut#jack krauser smut#aot smut#eren yeager#armin smut#armin arlert#mikasa ackerman#levi ackerman#levi ackerman smut

1K notes

·

View notes