#when you learn to see things through an appreciative lens you sometimes direct that viewpoint inward

Text

What I think is so important to learning how to truly appreciate life is learning how to appreciate the creatures and things we've categorized as "disgusting" or "gross."

When I learned to appreciate wasps, I realized how much they just... don't really care about anything, and they're not trying to be an asshole because they're uniquely cruel. If they have any wants, it is to live. Why would I punish that when I also want to live?

This isn't to say you need to fall in love with the creepy crawlies that stalk this world or to love what you cannot, but to recognize that in their arrangement of atoms, they are trying to persevere, and in the end... aren't we all?

#positivity#bugs tw#this is why i think science is a love language btw#learning to love and appreciate through study is still love and appreciation#i've always been fine with bugs which might make this ring hollow to somebody with a phobia#and this isn't saying that people who are phobic of bugs are Evil or dumb (quite the opposite- humans are Good at fearing things)#what this is saying is find something you don't appreciate and learn about why you should appreciate it - for whatever reason#i learned to stop being neutral about bugs when i learned how cool they are - how they live!#i stopped being neutral about this planet when i learned how ancient it is!#i stopped being neutral about humans when i learned about how we lived and survived and loved!#i stopped being neutral about these things because i started to love them because i saw just how intricate EVERYTHING is#when you learn to see things through an appreciative lens you sometimes direct that viewpoint inward#so now instead of viewing myself as outside the universe i see myself and every little bug as PART of the universe#i stopped believing that i almost... wasn't worthy of being Part of Nature when i realized just how big everything is in the scale of it al#you should see my google searches omfg#everything is an argument and boy does this world have the ability to argue so well

177 notes

·

View notes

Photo

What I miss most: “the liminal, magical space that is the live concert venue.” ~June 8, 2021

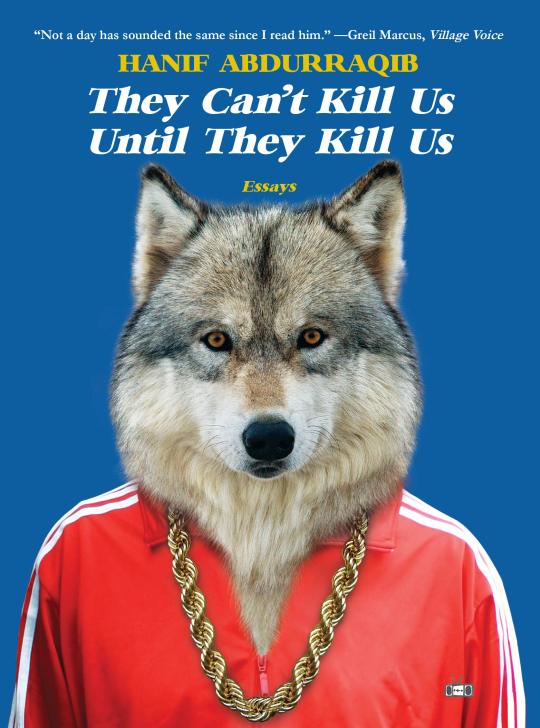

I’m so glad to have finally read this book after it was repeatedly recommended to me by several different friends. Hanif Abdurraqib has an absolute gift for crafting essays that braid his personal experiences with the (sometimes seemingly cosmic, and therefore daunting to explain or conceptualize) forces of racism, sexism, economic inequality, and nationalism in America. He also jumps seamlessly in scale and in scope, summarizing the heart of something hugely complex—a masterpiece album, a regional sound, a decades-long relationship—without reducing the irreducibly complex, without sacrificing specificity, without sounding trite. I don’t think I’ve ever read a book quite like this, although I haven’t read very much Creative Non-Fiction. Regardless, Hanif moves skillfully, masterfully. I love the collection’s confidence in narration, the love of language, the direct confrontation with that which makes us all deeply flawed (deeply human).

Each of these essays could stand alone. It’s a joy to read even one and Abdurraqib’s style shines through in just a couple pages. He crafts his stories with such dexterity. It’s clear that he comes from a background in poetry, as he celebrates language, builds vivid images, and thinks thematically. (I love the moments that are truly experimental—erasures of his own work, pieces without punctuation that flow on and on in one interlinked sequence). At the same time, he relies heavily on facts and content. Part of his conviction is born of research and depth of understanding. He knows his subject; yet, within this knowledge, he expresses personal preferences and sentimental love. I learned a ton from this book about music, about the history of particular musicians, about the relationship between racial inequality and self-expression within the field of music. Together, these essays form of complex tapestry of recent history in America seen through the lens of music. I absolutely loved the experience of coming to understand the interweaving of so many of our lives’ central questions and tensions through the history of music.

Art is inherently political, as many contemporary artists would agree (a viewpoint that counters the modernists before them who argued for the apolitical nature of art—art for art’s sake). Abdurraqib makes a very compelling argument for the deep integration of art with politics, social systems, economics, and trends. These things, however, are also deeply tied to the powerful forces of our choices, our identities, our love, and our compassion. It does not cheapen art of have it be so informed by, so shaped by political and social forces. In Abdurraqib’s worldview, art is the medium by which we reflect ourselves back to ourselves. And it’s also the medium by which we find freedom, by which we challenge ourselves to grow beyond the ways we understand ourselves to be. Race is the most central political and social theme that weaves throughout these essays, starting with the title of the book, which is introduced in the essay on Bruce Springsteen. “They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us” are the words that hang above Michael Brown’s memorial in Ferguson, Missouri. It might be hard to imagine an essay that weaves a Springsteen concert with a trip to Michael Brown’s resting place, a task that would certainly be daunting to any other writer, yet Abdurraqib navigates this with dexterity that seems natural, fundamental to how he thinks about the world.

Within the framework of race in America, some of the themes from these essays that I most appreciated and internalized included: Black joy (when it’s expressed and what it means), the markings of wealth (in the context of a journey out of poverty), and the policing of authenticity (or other forms of self-expression/emotion). Black joy is mentioned repeatedly in these essays, as something to be commented on for its rareness, while also positing the idea that music is a space that more boldly permits Black joy. Awareness of joy seems flow underneath these essays; it’s something not taken for granted, something treasured. I found this awareness of joy in the essay on Nina Simone’s Blackness and in the contrast between how she is portrayal by Hollywood and how she lives on in Abdurraqib’s childhood memories. I found this awareness of joy in the essay “Surviving Punk Rock Long Enough to Find Afropunk,” which focused on the exclusion of Black bodies from punk rock spaces (and the disregard for the handful of Black bodies that dared to enter anyway), while emphasizing the inherent survival in the African American experience that resonants deeply with punk rock’s values. A longing for a space that is joyful for Black people was addressed beautifully in the essay on Whitney Houston and Michael Jackson, in which Abdurraqib wishes for a home in the darkness of the photo of the two of them, where he sees “a small & black eternity.”

One of my favorite essays in the collection was the piece “Burning That Which Will Not Save You: Wipe Me Down and the Ballad of Baton Rouge,” which focuses on the rise of three Baton Rouge rappers—Foxx, Lil Boosie, and Webbie—in the years that followed Hurricane Katrina, which changed the outlook of Baton Rouge and its relationship to loud neighbor New Orleans. The essay breaks down the fundamental pieces of the rapper persona (circa mid-to-late 2000s): shoulders, chest, pants, shoes. For each of these elements, the essential nature of each is discussed, particularly as they relate to signaling both wealth and self-confidence: the dream realized. I loved this essay because it brilliantly articulated something I’ve always sensed (understood in myself in certain ways), but been unable to well-articulate, which is the power of “markings of wealth” in the life of someone who has survived through poverty, or an understanding of the proximity of poverty. For this person, the possession of wealth (things that show wealth, that communicate its presence to others, whether or not there is a real depth of wealth) feels and is different. Someone wears their wealth differently if they are conscious of it. This is a different look than that of the third-generation millionaire’s son for whom a real depth of security is so deeply ingrained as to limit the frame of imagination to always include it. I loved how this essay explained that wealth is not an universally proud/cocky look, but instead braggadocios, something that has a lot of context, a lot of nuance, a lot to do with environment and habit and understanding of temporary/permanent.

Sports, another space in which the economic and political forces of America come head-to-head with the personal and lived experiences of diverse Americans, also center several of these essays. Abdurraqib has a similar appreciation of sports—spaces of fandom, spaces of mass-appeal, spaces where the struggles and triumphs of a few become the struggles and triumphs of many—as he has of music. The social discussion around sports also holds a magnifying class to systemic racism, a process which Abdurraqib unpacks and examines. Serena Williams is discussed as an example of the policing of Black self-expression (policing how she expresses anger, how she expresses confidence, i.e. “too loudly” for the white Western world), topics also addressed in depth in “On Kindness.” “Black Life On Film” tackles the way violence is romanticized and compartmentalized as part of the Black experience, allowing an observation of violence for white viewers that is unhinged from a need to alleviate it, to address it. These same tensions and problems bubble forth in the dialogue around sports, as the eyes of the nation are turned to popular topics, which are filtered through (nearly exclusively, exhaustively) the same biased lenses.

As Abdurraqib develops these complex themes, he relies on a few central tools that are essential to his literary project. To point out these common tools is not to say that Abdurraqib only has a couple tricks up his sleeve. These aren’t “tricks” at all. Instead, these seem important to how he thinks about the world, things that are inseparable from his mode of observation.

His most central tool is the “parallel events” essay structure. With this approach, Abdurraqib details what happened for him personally as events occurred elsewhere that rocked the framework and landscape of America. A collapse of time collapses distance. Abdurraqib seems to have experienced many of these such moments of collapse, as he vividly recalls where he was and what he was doing as particular significant events unfolded. The eeriness of these experiences are not lost on a reader; we’ve all been there. To say that Abdurraqib has experienced many of these is to, perhaps, point out how much current events impact and rock him (as they always do those who belong to the groups that are, time and time again, targeted and destroyed in America). But it’s also, perhaps, to point out the precision of Abdurraqib’s memory. He holds onto details like a vice, capturing for us in painful and poignant specificity the situation in which he personally broke against the tragedy of the news (as the news breaks to us, we break against it, like waves). One of the delicate powers of Abdurraqib’s use of this essay structure is the way that his personal narrative is not cheapened, nor lessened when set up against the national event, the event we all remember. Instead, one is given the right urgency and the other given the right intimacy.

This technique for framing an essay (an experience, a life) begins in the essay “A Night in Bruce Springsteen’s America” in which a white older man at a Springsteen concert tells Abdurraqib he was at another Springsteen show on the evening Lennon was murdered. While this man wishes that “no one gets killed out there during the show this time,” there’s no world in which, for Abdurraqib, someone is not killed out there during this show. The cycle of loss that is stitched into Abdurraqib’s environment, his racial identity, is too great for him to ever hold that same hope. I think that this technique of parallel events (one personal and intimate, one tectonic and tragic) is best maximized in the short piece “August 9, 2014,” a poetic erasure of Abdurraqib’s own writing. In the main text, Abdurraqib recounts something that seems, on the surface, like an every day experience: another passenger complaining on the flight he’s boarding, a mother asking to switch seats so her son can look out the window. With the bulk of the text crossed out, the secondary narrative that emerges from the remaining words is of another mother asking for her son. The date in the title clarifies that this secondary mother-son narrative centers on the shooting of 18-year-old Michael Brown. The longing, the seeking, the asking of both mothers exists in a poignant overly. Perhaps what the mother on the plane asks for is trivial, all things considered, but Abdurraqib never dismisses her impulse to shelter her son, from fear, but, at the same time, to let him see the world beyond the plane’s window. The personal and small that occurs in Abdurraqib’s unique experience takes on the sacredness, the elevation of the cosmic, the tectonic plate shifts of death/life, and also the heralding in of a new/old era in America with the birth of the Black Lives Matter movement.

My favorite, though, of all these essays was “Fall Out Boy Forever,” one of the most personal in the collection. Abdurraqib places the loss of his closest friend to suicide into the context of the rise, fall, and rebirth (as if from the ashes) of the band they both loved. Abdurraqib’s long-term fan following of Fall Out Boy works like pearls on a string, moments in time that span years, yet unite into a collective personal narrative. This narrative rang so, so true to me, as someone for whom the bulk of the past six years has been shaped by my relationship to a specific band. Their narrative contains my narrative; my narrative contains their narrative. Their concerts, their albums, their successes, their growth—these things exist like glowing points on the thread of my experience. I recall my life within this thread, anchored by it. I know the previous time I was able to see my grandparents, down to the exact date three years ago, because it followed on the heels of a particular BTS album that played in my ears over and over that week. I know when and where I traveled within the timeline of their music. I know when my friendships blossomed, pinned to the backdrop that is their musical evolution. I know the ways they challenged and changed me, changed my writing, grew my sense of myself. I know how inseparable I am from BTS, and I saw this so poignantly reflected in Abdurraqib’s journey with Fall Out Boy.

Like any true fan (the fan who is not self-interested, the fan who is there for the ups and downs, the fan who is there for the real story), Abdurraqib observes the members of Fall Out Boy with such astuteness (this made me go and listen to more Fall Out Boy songs than I ever had before). I loved the way he captures the dynamic between the band members. He’s great at this in general (his insights into the intra-band relationships in Fleetwood Mac and the production of the album Rumors was also so engaging), but there’s a different intimacy, a different kind of care with Fall Out Boy. Abdurraqib’s ability to so clearly reveal his own close relationship with Tyler in the context of Fall Out Boy’s inner life is striking and heart-breaking—from Patrick’s frantic internalization of his music (performed for himself, yet in front of a crowd) without Pete’s complimentary/conflicting (necessary) presence when Abdurraqib seems him perform solo in Austin, to Tyler’s DESTROY WHAT DESTROYS YOU patch that Abdurraqib casts into the pit at a concert after wearing it to shows for years. To me, Tyler leapt from these pages, alive in the space where Fall Out Boy and their audience come together, transcending his own life’s timeframe in the liminal, magical space that is the live concert venue. This essay made me feel less alone in my experience of life perceived through the lens of music. This essay was Abdurraqib’s project at its most intimate, where the perception that happens through the lens of music is, most fundamentally, that of one’s self.

#they can't kill us until they kill us#hanif abdurraqib#music criticism#important reading#race in the context of music#art is inherently political#writing about race#writing about music#rap#hip hop#pop music#creative nonfiction#popular culture#black lives matter#fall out boy forever

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Real Reason why Personal Development is Crucial in Mediumship

https://ift.tt/2TXzMhI

The journey toward becoming a medium can be a very exciting one — full of first-time, mind and soul altering experiences. After all, coming to know the unseen world in very personal and passionate ways is incredibly fascinating and unique, and no one pathway is ever quite the same.

Along the road we take classes, workshops, seek out mentors, read a plethora books and venture on many roads-less-travelled in search of a powerful connection to ourselves, the spirit world and the universe at large. One thing however, that we can sometimes miss, is the call from within to tend to blocks and wounds that may exist within our very selves.

We can sometimes be so motivated to help the other – to find ways to ease the suffering and spur the growth and healing of those who might need our help – that we miss the very first and most crucial aspect of any spiritual work, which is healing the self.

Getting It Right With Personal Development

As intermediaries between the worlds, Mediums have the honor and privilege of relaying messages of importance from those in spirit to those here in the living. But along with that ever-important task, the vocation carries with it tremendous responsibility to ‘get it right’. But what does ‘getting it right’ even mean?

It has been a fascinating journey over years of teaching and mentoring new mediums to develop and hone their skills. Skill development alone is a long-term commitment. It requires care, attention, focused learning and practice.

Progressing from your first real contact with a spirit person to sitting as a professional in service to others (and being consistently good at it) can take years, indeed.

Development circles, classes and having peak spiritual experiences are all par-for-the-course in the unfoldment of a mediumship practice. And each of these aspects of development and learning are critical — absolutely required.

Expanding Soul Consciousness

In the teaching of hundreds of students, some of whom are excellent professional mediums, intuitives and healers, I have consistently found tremendous value, and in fact necessity, in moving beyond just the skill development aspects of mediumship.

As much as understanding and mastering the ‘mechanics’ behind spirit communication is an essential part of the learning process, so too is the development of greater levels of one's own soul-consciousness (you could also think of this as becoming more spirit-like, or shifting into a greater identity of self as a soul rather than just a personality). This process of transformation of identity or level of consciousness usually has to be preceded by some level of healing within the personality or ego bodies.

Guiding students to enter into their own wounding, in search of meaning, purpose and eventual healing, should probably be as much a part of the long-term syllabus in mediumship development as exercises and experiences with the formless.

Healing

Healing is a big word though, and it can get lost in a sentence quite easily. What exactly is meant by ‘healing’? I have always found the word itself needs to be understood more clearly, and in order to achieve that, we must anatomize it — we must unpack it a little.

Whether you are a student of mediumship or a soul-journeyer, the unpacking of the term healing is all-important. For me, healing is about extracting the learning that is available to you out of a negative or wounding experience, and then integrating that learning or growth into your life in a meaningful way.

The process of healing really begins when we are able to assign or identify some meaning and purpose behind the challenges, or behind the ache. Or we are able to see what good can come out of it – we realize and step into the power to create our life out of what we are left with, and we make something meaningful out of it.

In order to discover meaning and purpose and eventually enter into the healing, we must touch the wound. We must find it. And we must come to know it honestly — deep as ever.

No Mud, No Lotus

Photographer: Jay Castor | Source: Unsplash

This is the part of personal development that can be scary — because it can hurt. But with the right guidance or mentorship from a soul-based coach, counsellor, or other trusted and soul-conscious individual or professional, you can absolutely enter into the woundedness and shift into healing. It is a beautiful universal truth and promise that following the darkness, we will enter into light. The light, or the new version of ourselves, isn't about restoring who or what we were before. Rather, it is a re-birthing of our new selves.

But we must truly and authentically walk through that darkness, taking with us all there is to learn and know about the experience — no by-passing, no puddle jumping.

Walking through the mud is a good way to think of it…and the mud will eventually lead you to solid ground if you keep going. This truth is also demonstrated through the phrase, "No mud, no lotus".

We all have the choice to walk through the dark and make our way to the light, but conversely, we can also enter into the shadow and choose (consciously or unconsciously) to not walk through to the other side – into the learning, the freedom and the growth. Each of us has free will choice to do as we please. And may we never judge the choices of others, but rather see them (and ourselves) as we are with a heart full of love, compassion and kindness.

Understanding Universal Truths

Photographer: NASA | Source: Unsplash

Within the context of mediumship, shadow and wound work hold much relevance. When spirit people transmit messages, the messages are usually two-tiered in that they touch two levels of a reality; they touch the specific or particular and form aspects of a reality, and they are also steeped in the universal aspects of a reality – also referred to as a greater reality than what the form world so easily perceives.

Their messages at the surface can be specific and pertinent, and often very resourceful in nature. For example, “Getting fired from your job was necessary and essential for you, even though you can’t see how it’s beneficial from your current viewpoint. A new opportunity is sitting in the field of potentiality for you once you have done a little more processing of the anger and fear that surfaced after you lost your job. Consider being open to opportunities presented to you by a close female friend”. Behind (or more accurately, above) the resourceful message will be a universal truth being communicated. Strip away the details, and what is the spirit person saying?

Filtered upward into a universal nature or theme, this message is stating a number of universal realities that need to be communicated, some of which could include:

– All that we experience holds meaning and purpose, even if we can’t identify what they are right away

– Doors will close that are not meant for us

– Doors will open when the timing is right and appropriate for us, and not before or after

– There is no blame to be issued and the consciousness of blame is heavy and non-life-affirming

– While we have experiences within a life that are pre-planned by the soul, we also have free-will choice. This means that certain experiences will not come into our earthly life unless and until we have met other factors, which we reach through our own conscious choices to move forward and look at something with a deeper, more soul-infused lens

– Perceived negative experiences (wounds) highlight within us our own shadow – the parts of our soul consciousness that are not active, not identified with. In this way, woundedness is a powerful experience that points us in the direction of where we need to grow – it shows us our own shadow that is asking to be illuminated by the light of soul – it shows us parts of our soul that we are disconnect from and not identified with

– All woundedness teaches us to stop relying on others to fulfill the needs of our soul and empowers us to self-generate the qualities we want and need to experience. This puts us in a power position in our own life rather than in a victim consciousness. Because of this, we can and may eventually be grateful for the wound

Would you believe that in addition to the message specifically about being fired from a job, spirit wanted you to say all of this stuff, too? Well, they did, indeed. Fully transitioned souls in the otherworld are conscious beyond what we can perpetually obtain while here in form — while we are still influenced by and expressing through the form bodies.

The vibrational frequency of a transitioned spirit person far exceeds what we can achieve for any appreciable length of time while in form.

Their consciousness or lens through which they ‘see’ things is always one of knowingness, lovingness and power, and as such, they want to impart this level of insight and wisdom to their loved ones here in the physical world. Why? Because they want to help in our understanding, healing, and growth.

Honoring the Role of Messenger

This leads us to our own growth, healing, and understanding of the nature of spirit and the universe at large. Because spirit people wish to have universal truths and realities communicated to their loved ones here in the physical, and we as mediums have made a commitment to honor the role of messenger, then we must be equipped to share the messages; undistorted, unfiltered, unbiased.

If we do not tend to our own personal work throughout the journey of becoming intermediary between worlds, then we will have no personal understanding of universal truths because we will not have experienced the manifestation of those realities in our own lives. If we have no lived experience, then how will we be able to communicate these levels of truth to someone else?

Universal truths such as: our thoughts and beliefs create our experiences, consciousness or soul survives physical death, hard experiences are teachers for us, we have agreements with others souls in our life, everyone is doing the best they can from the level of consciousness they have in the language of the universe there is no pass or fail, there are simply experiences, etc. are best known and expressed to others from a place of lived experience.

If we have not successfully walked through some level of wounding to healing ourselves, how can we help lead someone else there, authentically?

There is a case to be made for any individual in walking into hurt and pain for the purposes of emerging more empowered, more loving, more understanding, and more soul conscious. Becoming greater versions of ourselves is one of the gifts we can give ourselves during the earth walks we choose. The case is of even greater importance for those who wish to be the messengers for the other side.

if(window.strchfSettings === undefined) window.strchfSettings = {}; window.strchfSettings.stats = {url: "https://the-otherside-press.storychief.io/personal-development-in-mediumship?id=12776853&type=2",title: "The Real Reason why Personal Development is Crucial in Mediumship",id: "ff9f9eef-5765-4d6d-bd86-ed78b42ea041"}; (function(d, s, id) { var js, sjs = d.getElementsByTagName(s)[0]; if (d.getElementById(id)) {window.strchf.update(); return;} js = d.createElement(s); js.id = id; js.src = "https://d37oebn0w9ir6a.cloudfront.net/scripts/v0/strchf.js"; js.async = true; sjs.parentNode.insertBefore(js, sjs); }(document, 'script', 'storychief-jssdk'))

from The Otherside Press https://ift.tt/2FRSsug

via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

What IS A Dolphin? The Idealist vs Pragmatist

I just started my second (and final) year of my master’s program in forensic science. One of the classes I’m taking is called Foundations of Criminal Justice, which is deliciously philosophical. And believe it or not friends, I have found some interesting parallels in the marine mammal world with some of the stuff I have been reading in my textbook.

This is my life right now

In the second chapter, the author writes about idealists versus pragmatists, and how they would develop and implement aspects of the criminal justice system. But the thing is guys, the author used an animal to illustrate the difference between the two perspectives. And I realized HOLY CRAP THIS IS IT. THIS EXPLAINS THE MAIN DISSONANCE BETWEEN THE GENERAL PUBLIC AND THE REST OF US.

So let's just not pay attention

To put it bluntly, idealists tend to develop an idea about something without much (or any) legitimate facts/evidence to support it. Their goals are led by what they believe is the right or wrong ways to view/do things. Pragmatists take a scholarly approach, letting the evidence and systematic observation of events or data develop and flesh out the goal. So I'm reading this and then boom, suddenly I read how an idealist sees a dog (heroic, loyal, Rin Tin Tin) versus a pragmatist (something that pees in the house and eats all of your cupcakes). And it is basically exactly like how most people see dolphins.

Dog-shaming is definitely an exercise in pragmatism

I could focus all my energy on school and really hone my understanding of this concept through the lens of my next chosen field, but I decided it would be better off in a blog.

Here are some major idealist (read: most of the general public, including myself before I became a dolphin trainer) concepts of dolphins, and the pragmatist (zookeeper) response. Bold is idealist, normal font is pragmatist.

Dolphins live in tropical waters that are also 78,000 feet deep

This is especially directed at obnoxious ARAs

Wrong. Raise your hand if you have told someone about dolphins living in cold water and they look at you like you just ate someone else’s toenails. I’ve encountered this when talking to guests about where they can go whale-watching in New England and geek out on the chance that they will see either Atlantic white-sided or white-beaked dolphins and they are like, “Uh, you moron, dolphins don’t live in cold water.”

Or these guys, who can ONLY live in cold water

The other bizarre part of this is that some idealists (myself included!) are shocked to learn that in many cases, warm water dolphins live in pretty shallow water, because that is where the fish are. Until I moved to Florida, I thought all fish lived in deep water because like…you know, the bigger the fish tank the better or something.

Dolphins will save drowning or distressed swimmers

Don't count on dolphins helping you

Okay, this may have happened once or twice. Maybe. But most of the time, if you get into trouble, dolphins will just sit underwater and laugh at you. Or think, “Wow, that sucks. Not my problem.” Sounds a little familiar.

Dolphins are gentle creatures who live in peaceful societies

Amiright

Plants don’t even live in peaceful societies. Next question.

Dolphins are extremely intelligent and are friendly towards people

KNOW THE TRUTH

Yeah, those of us who know dolphins know that they are individuals whose intelligence and friendliness exist on a pretty broad spectrum.

But the fact is, there are Jerk Dolphins out there. Usually, they are the insanely smart ones. They WILL steal your iPad. They WILL bite your toes. They WILL zoom into one of your guest’s um, male nether region. They will dismantle hardware in the habitat and hide all the pieces so you freak out for hours trying to locate them while the guilty dolphins look at your and laugh and laugh and laugh and laugh

Dolphins are the only animals other than humans who have sex for pleasure

Side note: IT IS BASICALLY ALMOST HALLOWEEN

I admit, I bought into it when I thought that dolphins were somehow “higher” than other animals (and when I thought that there was such a linear ladder of intellectual and behavioral complexity in animals, silly me). However, sex should feel good for at least one party in sexually-reproducing animals, otherwise it wouldn’t happen.

It’s not like a horse suddenly gets this idea in her head, “Oh, I can just magically tell I am ovulating. Better find a genetically-fit stallion so we can copulate and contribute another data point to the Selfish Gene Hypothesis.” No. Like the rest of us (dolphins included), the chick horse is like, “I NEED A MAN. THAT GORGEOUS ONE OVER THERE. GET OVER HERE AND DO GOOD WORK, SIR.”

...and zookeepers are over here like....

Dolphins do use sex as a social tool more than some other animals, but they are not the only ones to do so (bonobos and gold diggers are classic examples).

All dolphins want to do is play

World domination is serious

No. Sometimes they want to eat. Sometimes, they want to sleep. Other times, they sit around and plot the demise of humans (spoiler: they are well on their way).

I've worked with a couple of dolphins who were just business-oriented, both in and out of sessions. They would play once in a while, but for the most part they were basically like Dwight Schrute.

MARRY ME DWIGHT

Most of us have idealist viewpoints on many subjects, and that is not a bad thing. I don’t really think it’s a good idea to be firmly in one camp or the other. And it is easy to move from one to the other, especially when it comes to an understanding of animals and what they are like as a species AND as individuals. I definitely learned a lot more about dolphins after actually working with them, despite all that I had read and studied.

And while I am poking fun at the generalized, incorrect myths of dolphins people believe, I also realize that you know what? That's how our brains work, until we get new information to assimilate into our understanding. In the case of understanding animals, the job of a zookeeper is to provide accurate information to our guests who may think that all dolphins are nice, or that rattlesnakes are evil, or whatever misconceptions they have about their generalized idea of whatever species. Having an “idealist” concept of an animal doesn’t mean you are dumb. It just means you get to learn some more cool facts, and have an even BETTER appreciation for that critter!

from The Middle Flipper http://ift.tt/2eRL7hH

0 notes