#timor leste

Text

In Dili, Indonesia’s future means trying to forget about Timor-Leste’s past

Indonesian President-elect Prabowo Subianto, a former military officer, has been linked to alleged atrocities in Timor-Leste.

At Timor-Leste’s museum of memory, Hugo Fernandes supervises exhibits chronicling resistance and oppression during the Indonesian occupation – an era when Prabowo Subianto, now Indonesia’s president-elect, is alleged to have overseen atrocities.

Fernandes runs the Centro Nacional Chega! museum, a former prison in the capital Dili that dates to when Timor-Leste was a Portuguese colony. Faded photographs of Timorese resistance fighters and messages scrawled on the walls by prisoners who languished here during Indonesia’s brutal 24-year rule line its galleries.

Despite the shadows cast by history, the impending ascent to power of Prabowo, a former army special forces commander who was declared the winner of the Feb. 14 Indonesian general election, has been greeted with diplomatic decorum in this tiny young nation of 1.3 million people also known as East Timor.

“Prabowo’s specific actions remain unclear due to limited information,” Fernandes, the museum’s director, told BenarNews. “Accusations of human rights violations have persisted, but concrete evidence and verification are difficult to obtain.”

“Chega!,” which means “enough! in Portuguese, stands as a testament to Timor-Leste’s efforts to navigate the delicate path between preserving the memories of its dark past and promoting reconciliation with its giant neighbor next-door.

“There are differing voices within the nation,” Fernandes says. “Some activists advocate for answers regarding past atrocities, while others emphasize the importance of moving forward with Indonesia.”

In 1999, East Timor voted overwhelmingly to break away from Indonesian rule, through a United Nations-sponsored referendum. Before and after the vote, pro-Jakarta militias engaged in widespread violence and destruction. East Timor gained formal independence in 2002 after a period of U.N. administration.

The occupation, which followed after Indonesia invaded East Timor in December 1975, was marked by famine and conflict. The number of deaths attributed to that era ranges from from 90,000 to 200,000, the Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation in East Timor reported.

This figure includes nearly 20,000 cases of violent deaths or disappearances. The commission’s findings indicate that Indonesian forces were responsible for about 70% of these violent incidents, set against the backdrop of East Timor’s population of around 900,000 in 1999.

And according to the Genocide Studies Program at Yale University, “up to a fifth of the East Timorese population perished during the Indonesia’s 24-year occupation … a similar proportion to the Cambodians who died under the Khmer Rouge regime of Pol Pot (1975-1979).”

Since 1999, the relationship between Timor-Leste and Indonesia has evolved, with Jakarta acknowledging its former province as a “close brother” and supporting Dili’s bid to join the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).

Timor-Leste President José Ramos-Horta welcomed Prabowo’s election win and expressed readiness to collaborate with Indonesia’s upcoming new leader.

“Very pleased, very pleased,” Ramos-Horta told BenarNews when asked about Prabowo’s victory.

As a young man, Ramos-Horta, now 74, was a founder and leader of Fretilin, the armed resistance movement that fought to liberate East Timor from the Portuguese first and then the Indonesians.

He said he had personally called Prabowo, now Indonesia’s defense minister, to congratulate him, and that the ex-general planned to visit Timor-Leste before his inauguration on Oct. 20.

Prime Minister Xanana Gusmão, a former guerilla leader who spent years in an Indonesian prison, was also happy with the news, Ramos-Horta said.

“President-elect Prabowo will contribute a lot, first to Indonesia, continuing stability and prosperity in Indonesia, and then in the region, as well as strengthen relations with Timor-Leste,” he said, adding Prabowo had “many friends” in his country, including his own brother, Arsenio.

When asked about Prabowo’s human rights record in Timor-Leste, Ramos-Horta said, “That is past. It’s already almost three decades, and we do not think of the past.”

Prabowo was a key figure in the military operations that crushed the East Timorese resistance.

The Timor-Leste National Alliance for an International Tribunal (ANTI), a coalition of civil society organizations, survivors, and families of victims, said reports had implicated Prabowo in a 1983 massacre in Kraras.

Some estimates said that 200 people were killed there, earning the area the nickname the “town of widows.”

In a statement released in November, the alliance said that as the head of the Indonesian army’s special forces command, Prabowo had directed actions resulting in severe human rights abuses and crimes, including the establishment of pro-Indonesian militias blamed for post-referendum violence in 1999.

In addition, Prabowo is linked to a 1991 massacre at the Santa Cruz cemetery in Dili, where some 250 peaceful demonstrators were killed, the alliance said.

In 1998, Prabowo was discharged from the military after a council of honor officers found him guilty of several violations, including involvement in the abduction and disappearance of pro-democracy activists during the 1998 student protests that led to the downfall of Indonesian dictator Suharto.

Prabowo, 72, has denied any wrongdoing and said he was only following orders from his superiors. He has never been tried in a civilian court for the alleged crimes.

Prabowo’s presidential campaign team said that witnesses, including religious figures in Timor-Leste, had denied his connection to the Krakas killings.

For many Timorese, the memories of Indonesian occupation are hard to erase.

Naldo Rei, 50, a former child guerrilla-fighter who was repeatedly imprisoned during that period, said he could not overlook Prabowo’s human rights record.

“While I don’t want to meddle in Indonesia’s internal matters, when it comes to human rights issues, Prabowo has a very distressing track record,” Rei told BenarNews, his soft-spoken and gentle demeanor belying his resistance years.

Rei spent his youth evading capture in the Los Palos jungle after the loss of six family members, including his father, to Indonesian military action.

In the early 1990s, he sought refuge first in Jakarta, then in Australia, before settling in an independent East Timor.

Rei, who is the author of “Resistance,” a memoir detailing his experiences, voices apprehension about the trajectory of Indonesian democracy.

“Prabowo’s victory, from my perspective, squanders the democracy that the people have fought for,” he said. “How many lives have been lost? He and other generals have blood on their hands.”

Januario Soares, a second-year medical student at the National University of Timor Lorosae, represents a growing sentiment focused on the future.

“Indonesia has chosen its leader. We need to focus on the future,” Soares said as he sat in the shade of a mahogany tree outside his campus in Dili.

He believes strengthening relations between the two countries is vital.

“The civil war left us divided, and in that division, we inadvertently opened our doors to Indonesia,” Soares said. “What followed was a period of violence against our people, a scar in our history.”

Yet, when it comes to Prabowo’s role in that history, Soares admitted he did not know much.

“The Indonesian people have made their choice. Perhaps Prabowo is the best among the contestants; that’s why they chose him,” he said.

Soares said he opted for a pragmatic approach toward the past, focusing on improving the quality of life and seeking benefits for the present and future.

“People change over time, and I believe Prabowo has changed too.”

Damien Kingsbury, a political expert specializing in Timor-Leste, said Timorese leaders were obligated to maintain a delicate diplomatic stance due to the small nation’s reliance on Indonesia for imports and its aspirations to join ASEAN, the Southeast Asian bloc. Indonesia is one of ASEAN’s founding members.

“Of course, Ramos-Horta must be diplomatic,” said Kingsbury, a professor at Deakin University in Australia, who has written extensively on Timor-Leste and Indonesia.

“He is president of a small country that has an unhappy history with Indonesia and does not want to create any possible problems,” he told BenarNews.

Kingsbury pointed out that while Ramos-Horta, a Nobel laureate and prominent diplomat, is well-versed in the language of diplomacy, there is a generational gap in awareness of the nation’s tumultuous past.

“Younger people may not be aware of events of 20, 30 and 40 years ago, but that does not mean they did not happen,” he said.

“It must leave a bitter taste in the mouths of many that Timor-Leste’s leaders need to be polite to Prabowo.”

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

An illustration of the folklore Liurai of Ossu from Timor Lorosae.

We made an illustrated book filled with folklore and tales from South East Asia, check it out here.

#book illustrations#timor leste#timor lorosae#folklore from south east asia#broken gun#flowers#fern#tales of eleven#oracle of eleven#hibiscus#dove#a call for peace#folklore from timor loroase#south east asian folklore

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Please reblog for a bigger sample size!

If you have any fun fact about East Timor, please tell us and I'll reblog it!

Be respectful in your comments. You can criticize a government without offending its people.

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dili, Timor-Leste

#dili#timor-leste#timor leste#asia#southeast asia#dailystreetsnapshots#travel#photography#street#streets#places#blue skies#ocean#beach#tropical#tropical places

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Population: 277,488

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Comment:

The Australian public's relationship with the East Timorese is close, especially after the nightmare years of Indonesian occupation from 1975 ended with the independence vote in 1999.

Not suprisingly, Australia's more liberal, if evolving views on same-sex relationships has made it a magnet for same-sex folk from all over Asia, and the huge talents and passion they bring. Our East Timorese refugee community is no different, and now it is having a mimetic effect by example - brilliant!

Extract:

“Timor-Leste, with all the trauma that it has been through to the fact that through grassroots coordination have been able to hold their own Mardi Gras, is quite remarkable,” [Nuno] Carrascalão said. “There is a common thread that the fight for independence is the same fight for equality.”

During Carrascalão’s visit, he met with the president – José Ramos-Horta – and helped organise for the next year’s Timor-Leste pride parade to end at the presidential palace.

Despite these advances, LGBTQ+ people still face a frequent lack of acceptance, violence and discrimination, Guterres said, something he hoped having a Timor-Leste float as part of Sydney’s Mardi Gras could change.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

East Timor

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

For Timor Leste Independence Day, I’ve put together a hype playlist for East Timor pride. Please give it a listen https://open.spotify.com/playlist/4fqjJ2RRbDVUXavzyGcxwg?si=rsrA2HzIQk6TDGsCvgrSJQ

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Timor Leste by Dana Irfan

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

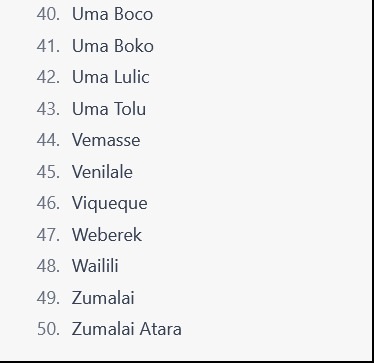

I've checked a lot of these, and most of them are real settlements, according to Google Map or Google at large. At least two of them are major settlements, and a few of them I can't figure out what they are, but it starts off basically ok. Later on you'll see it duplicates a couple, with alternate spellings. A lot of them seem to be too big to be villages.

But 'Uma Lulic' is the one I'm most interested in, because as far as Google can tell, there is no such settlement. In Tetum it means 'sacred house' and they are a common tourist attraction. It seems that ChatGPT has made up a village, by picking a plausible-sounding Tetum name. Then again, I don't actually know anything about East Timor, so maybe it's just a very obscure settlement.

Zumalai is an administrative region, and as far as Google can tell, there is no Zumalai Atara.

If anyone has more information, I would be interested to know.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Não vão todos ao mesmo tempo..."

1 note

·

View note

Text

Asia’s youngest nation emerges as a voice of conscience on Myanmar

Two decades ago, freedom fighters on a mountainous island in southern Indonesia won a long, bloody struggle against a corrupt military regime, establishing East Timor, also known as Timor-Leste, the first independent state of the 21st century. Memories of airstrikes and indiscriminate killings are still fresh here. And they’ve led the country’s leaders to take an unusual interest in another fight for freedom in Southeast Asia.

In 2021, a group of generals overturned an elected government in Myanmar, formerly known as Burma, starting a civil war that some conflict monitoring groups consider the most extreme in the world today. Many countries have looked away — much as they did for 24 years, East Timor’s leaders say, as Indonesian soldiers fought Timorese independence fighters.

“For so long, nobody paid attention to us,” Xanana Gusmao, the prime minister of East Timor, said during an interview in the capital, Dili.Gusmao led the insurgency against the Indonesian military, later serving two terms as East Timor’s president and now, his second as prime minister. At 77, with a head of white hair and a stiff back from years of imprisonment, he still remembers every person he saw killed or tortured in the jungles of Timor, he said.

“I do not accept the suffering of the Burmese people,” Gusmao said. “I cannot.”

Many in East Timor, even opposition politicians and civil society leaders critical of Gusmao on other issues,said in interviews that they agree. The country of 1.3 million, with an economy one-seventh the size of Vermont, has gone further than almost any other in supporting the Myanmar resistance, receiving its leaders as state representatives and openly advocating on their behalf at international forums.In the coming months, East Timor will let Myanmar pro-democracy groups open offices in the country to help coordinate resistance activities and take in a number of political refugees, officials say.

Increasingly, human rights activists say they see Dili as a voice of conscience, challenging more powerful countries that have been too distracted or too divided to press for change in Myanmar. “What the Timorese are doing is vital,” said Debbie Stothard, a Malaysian rights advocate.

Regional inaction

The U.N. Security Council has repeatedly called on Myanmar’s military government to comply with a peace plan adopted by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), and Western officials, including from the United States and the European Union, have also cited that plan for resolving the conflict.

But ASEAN, which operates on a principle of “noninterference” and includes Myanmar as a member, has largely failed to convince the junta to cooperate.

In 2021, ASEAN adopted the “Five-Point Consensus” on Myanmar, which calls for a cessation of violence and a dialogue among all parties. The junta signed the plan but has ignored it with little consequence. The military has ramped up airstrikes to a rate of nearly once a day, according to conflict monitoring groups, and faces mounting allegations from human rights groups of carrying out mass killings, beheadings and other atrocities. Myanmar has declined invitations from ASEAN to meet with resistance leaders.

“The five-point consensus has failed,” said Saifuddin Abdullah, who served until last year as foreign minister for Malaysia, an ASEAN member. The plan, which has no enforcement measures, is being disregarded not only by the Myanmar government but by other ASEAN members, Abdullah said.

In April, Thailand’s foreign minister traveled to Myanmar and met with junta leader Gen. Min Aung Hlaing without notifying other ASEAN members. Thailand, which borders Myanmar, has also hosted secret meetings with junta officials and mooted the idea of ASEAN “fully re-engaging” military leaders.

By normalizing relations with the Myanmar opposition, East Timor is trying to pull the region in the opposite direction — but at some risk to itself. The country is in the final stages of negotiating admission into the bloc and was allowed last year to attend meetings as an “observer.” Its outspoken stance on Myanmar could jeopardize its application or otherwise alienate some of its neighbors, analysts say.

East Timor can’t afford to be excluded from ASEAN, Gusmao admitted. With more than 40 percent of its population living in poverty, the country is in dire need of foreign investment. It has 15 years to find an alternative to its dwindling petroleum revenue, according to the International Monetary Fund, and has struggled since independence to feed its people,a problem set only to worsen with climate change.

At the same time, political scientists say, the country’s history has made it particularly sensitive to authoritarianism. East Timor has become probably the most robust democracy in Southeast Asia, according to experts.It’s the only country in the region ranked “free” by the think tank Freedom House and was recently listed 10th in the world for press freedom by Reporters Without Borders.

Smoking as he paced a meeting room in Dili’s government palace, Gusmao said that when he watches extensive coverage of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on television, he often thinks about suffering elsewhere, in Yemen, Somalia, Myanmar. Powerful countries aren’t obliged to care about crises that don’t affect them, Gusmao said.

Among small, fragile nations, he added, “all we have is our solidarity.”

A diplomat expelled

When Gusmao was inaugurated in Dili two months ago, a visitor from Myanmar was seated in the front row alongside cabinet ministers and diplomats from various countries. It was Zin Mar Aung, foreign minister for Myanmar’s National Unity Government (NUG), formed in opposition to the junta after the coup.

That event marked the first time any country had formally received an NUG official and sparked indignation from Myanmar’s military government, which demanded that Dili cut contact with what it called “terrorist groups.” The following month, when East Timor hosted a second NUG official in Dili, the junta expelled Avelino Pereira, East Timor’s top diplomat in Myanmar.

While some countries have downgraded diplomatic relations with Myanmar, the junta had not thrown out any foreign representatives until Pereira and hasn’t since.When other governments meet with opposition officials, they’ve done so privately or informally. Dili’s actions were “public and senior level barbs” at the junta, said a Western embassy official in Yangon, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because that person had not been given authority to speak on the issue.

“It showed great courage,” said Aung Myo Min, the NUG’s minister for human rights, the second opposition official to visit Dili. “It empowers us to know we’re not alone.”

Some Timorese officials worry Pereira’s expulsion could affect the country’s ASEAN bid. But President Jose Ramos-Horta, who was behind both invitations to the Myanmar opposition figures, said he was unperturbed. “It was an honor,” he said, eyes crinkling behind dark Ray-Ban sunglasses during a recent interview as he was traveling between official engagements in Dili.

Ramos-Horta, who shares the 1996 Nobel Peace Prize with Bishop Carlos Filipe Ximenes Belo for his opposition of Indonesian oppression, led the “diplomatic front” for East Timor’s sovereignty. Over years, Ramos-Horta formed alliances with activists from other countries, including Myanmar.

In recognizing Myanmar’s opposition government, Ramos-Horta, 73, said he was paying back the support that Myanmar pro-democracy groups gave East Timor. But he was also, he said,acting in line with historical precedent: During World War II, the Allied powers recognized Free France, a government in exile, over the Vichy government that collaborated with Nazi Germany.

“Are we supposed to accept the norm that elections can be disregarded?” asked Ramos-Horta. “The answer, at least for us, is no.”

‘Who is listening?’

When Gusmao attended the semiannual ASEAN summit in August, he was feeling contrite, he said.

He’d been chided by his staff a few weeks earlier for saying East Timor would reconsider its ASEAN application if the bloc couldn’t end the violence in Myanmar. Those were “uncontrolled” remarks, he reflected later, and at the summit in Jakarta, he had intended to stick to his prepared speeches.

But faced with leaders from the United States, China and Russia, Gusmao decided again to go off-script. News reports had said Aung San Suu Kyi, Myanmar’s deposed civilian leader, was ill, Gusmao told the room. The junta should provide medical care, he appealed. No one responded.

“We will speak out, always. But we are a small country,” Gusmao said as he recounted the incident. “Who is listening?”

Diplomats and aid workersin Dili say Gusmao and Ramos-Horta might have a bigger impact than they know. The two leaders have allies in places from Europe to Africa, and they command respect as that rare breed of statesmen who fought for freedom and won, said Olufunmilayo Abosede Balogun-Alexander, the U.N. resident coordinator for East Timor. On the world stage, she added, “they have an outsize voice.”

Earlier this year, at the World Economic Forum meeting in Davos, Switzerland, Ramos-Horta said he watched as heads of state and chief executives rose one after another to lambaste Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and rally Western governments to supply Kyiv with weapons. He was stunned, he remembered, that virtually no one mentioned Myanmar.

“Next year, I will,” said Ramos-Horta, days before departing for the U.N. General Assembly session last month in New York, where he again met with the NUG. “I will say something,” he continued. “So at least people there will hear the word, ‘Myanmar.’”

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

3 mars : le Timor oriental célèbre ses anciens combattants contre l’Indonésie

Le Timor oriental célèbre la Journée des anciens combattants (Dia dos veteranos). Ce jour férié a été créé pour honorer ceux qui ont lutté pour la souveraineté de leur pays pendant l'occupation indonésienne du Timor oriental de 1975 à 1999.

L'occupation indonésienne du Timor oriental avait duré de 1975 à 1999 et a entraîné la mort d'environ 100 000 à 300 000 personnes. Le Front révolutionnaire pour un Timor oriental indépendant (FRETILIN) avait tenté de résister à l'invasion. En 1978, le leader du FRETILIN Nicolau dos Reis Lobato avait été tué par les forces spéciales indonésiennes et la branche militaire armée du FRETILIN s’était engagée dans une guérilla contre les occupants lors d’une Conférence nationale de la résistance, le 3 mars 1981, c’est le 45e anniversaire de ce sursaut de la Résistance qui est célébré aujourd’hui.

Les célébrations ont débuté le 1er mars par une messe à 9 heures du matin à l'église paroissiale de Balide à Dili. S'ensuit une marche depuis Dili jusqu’au Jardin des Héros et Martyrs de la Patrie, à Metinaro, pour y déposer des fleurs ; suivi d’une fête au siège du Conseil des Combattants de Libération Nationale (CCLN). Le 2 mars, un séminaire s’est tenu au Convention Center (CCD) de Dili, avec des conférences du lieutenant-général à la retraite, Lere Anan Timur, du ministre des Affaires des combattants de libération nationale, Gil da Costa. Monteiro « Oan Soru » et le ministre de la Défense, le commodore Pedro Klamar Fuik.

Enfin, ce 3 mars, Journée nationale des anciens combattants, les célébrations se déroulent au Palais du Gouvernement, à partir de 8h15 avec la levée des drapeaux du RDTL, les discours officiels et la marche des anciens combattants vers le CCD, où un déjeuner de célébration est offert et avec des activités se déroulant jusqu'à 15h30, moment où le drapeau national est abaissé.

Au Timor-Leste, les « héros du pays » disposent de leur propre institution pour défendre leurs intérêts et bénéficient de certains privilèges, comme l'accès aux soins de santé à l'étranger et, pour leurs descendants, d'un régime différent d’admission à l'Université nationale du Timor-Leste. Cette année, l’argent public alloué au ministère des Affaires combattantes et de la Libération nationale (MACLN), à celui prévu pour l’ensemble du secteur de la santé du pays, en l'occurrence le ministère de la Santé. Ce traitement réservé aux anciens combattants par rapport au reste de la population est critiqué par de plus en plus de Timorais qui dénoncent l’existence d’une caste de privilégiés issue des cadres de la Résistance. Alors que cette année, pour le 25e anniversaire de la fin de l’occupation indonésienne, le slogan est « Ensemble, nous marcherons vers l'avenir ».

Un article de l'Almanach international des éditions BiblioMonde, 3 mars 2024

0 notes

Text

John Pilger

Sad to learn of the recent death of the Australian-born journalist John Pilger. He was a fearless and highly-awarded documenter of atrocities in the late 20th century, including the Australian treatment of Aboriginals, the war against Vietnam, the genocide in Cambodia, the brutal Indonesian invasion of East Timor, the plight of Palestinians, the Northern Ireland Troubles, and more recently his advocacy for Julian Assange and the vital importance of a free and independent press.

#journalism#john pilger#obituary#stolen generation#khmer rouge#cambodia#killing fields#vietnam#east timor#timor leste#palestine#northern ireland#troubles#julian assange#free press#freedom of the press#oppression#genocide#brave

0 notes

Text

Yamaha STSJ Beri Apresiasi Komunitas Maxi Yamaha Setelah Turing Timor Leste

Maxi Yamaha – motorrio.com – Kegiatan touring menjadi kegiatan yang banyak digemari oleh para bikers di Indonesia. Selain dapat berbagai hobi dalam menikmati kegiatan berkendara, aktivitas touring juga merupakan sarana untuk bersilaturahmi bersama dengan para bikers lainnya. Hal tersebut juga dilakukan oleh Komunitas skutik MAXI Yamaha yang dikenal dengan Komunitas GOMAX Adventure yang baru saja…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Video

youtube

DJ FINALISTA ( DL TERRA SANTA) SLOW REMIX - Musik Timor Leste Foun 🇹🇱 - ...

1 note

·

View note