#these each serve the same function within their respective appropriate genres

Text

here's a hot take for today

the narrative function of sex is the same as the narrative function of fight scenes is the same as the narrative function of songs in a musical

no i will not explain

#taz talks#writing#actually i WILL explain but i'll do it in the tags#these each serve the same function within their respective appropriate genres#each one is a kind of revelation#they heighten the connection between 2+ characters and highlight relationships and feelings and needs#they are out of place in genres where they do not belong and/or as curveballs when the narrative did not provoke them from the start#but they have the same sort of emotional/dramatic build-up#talk -> sing -> dance (talk -> yell -> stab) ((talk -> flirt -> You Know))#and they are all expressions of intense physicality and intimacy through physical gesture and interaction#they are fundamentally empty and boring if there is not a deeper purpose or drive behind them#although they can still occasionally be entertaining on their own if your audience is specifically seeking that experience out#people who do not like them will be very unhappy to encounter one where it isn't supposed to be#it is very easy to ruin the mood with poor word choice#many people have an inherent sense for terrible ones but it's often difficult or complicated to explain precisely why a bad one fails#when executed properly they are a very raw and intimate expression of a character's most fundamental needs and desires#the fluff is stripped away and there is nothing left but a series of needs. conflicting or cooperating.#and even when you're lying during one it's still a form of truth#none of these things are remotely necessary to tell a powerful or compelling story but if you're going to use them you need to do it right#also all 3 of these things are difficult if not impossible to write if you are not both interested in them and personally invested#this post brought to you by me trying to write smut about my dnd characters and failing because i generally hate /reading/ smut#so i have none of the vocabulary or instinct for it that i do for. say. graphic violence (or lyrical poetry)

190 notes

·

View notes

Text

Darkstar headcanons:

Laynia dresses in primarily dark cool colors with bright accents in the form of trims, patterns, or accessories. Due to coming from cold Russia, short bottoms aren’t in her wardrobe and most of her sleeves are long. She favors high-necked blousy belted tops with sleek pants and functional but pretty boots. Her long blonde is eternally pushed back. by some sort of headband. Cloth, plastic, wood, plain, pearls, bejeweled, patterned, she has them in near every variety possible and they are her most common accessory. She also owns a large assortment of stylish winter coats, scarves, gloves, and hats. Because, again, Russian. She's not much one for bracelets, preferring brooches and pendants more, typically in oval or starburst shapes. She has a love for black velvet, and it will show up for dressy events in forms such as a rhinestone-dotted envelope handbag or round-toed pumps with ankle straps.

Laynia collects small antique music boxes and crystal glass figurines of pretty things like ballerinas and swans. She likes black velvet jewel pillows, black flowers and black butterflies, gemstones (clear, black, or yellow) all sorts of museums (but especially art, astronomy, and natural history) and the sight of pure white snow under the street lamps at night before people can ruin it into dirty slush the next day.

She listens to classical, romantic, disco, pop, and synth music.

Laynia likes sweet delicate desserts like rock candy, powder candy, jujubes, marzipan, and bliny or oladyi with varenya style fruit preserves. She dislikes zhurek, tukmachi and any kind of preserved fish dish (fish should only be served fresh or not at all!)

She dislikes being asked about Putin, the Romanovs, etc. Basically, about the only things Americans know about Russian culture. She also dislikes how people don’t know the different between Russian and Belarusian.

Her favorite animals are white weasels/minks (because they're so pretty and cute) and wolves (because they're beautiful too, but also such social animals with strong family dynamics)

Laynia likes “slice of life” fictional media, such as domestic drama novels or family-centered sitcom shows. These are fantasies for her, these are escapes from what’s “normal” in her life. For the same reason, she avoids spy thrillers and similar genres, no matter how unrealistic they are in their depictions. She delights in mundane tasks.

Likes working in small groups (3-6 people counting herself), dislikes working alone or large groups.

She anthropomorphizes the Darkforce, calling it "she" and believing it has feelings or at the very least is capable of pain. What she actually feels when she feels the Darkforce in "pain" is due to simply her mental connection to her own Darkforce constructs that allows her to create, maintain, and manipulate them. When they are attacked, dissipated, or changed against her will, she feels that as pain, and interprets it as the Darkforce being in pain "herself"

Though not religious aside from a vague conception of Heaven and its goodness/judgement, Laynia is a strong believer in the supernatural, in particular of ghosts. She is not, however, a fan of them, and would prefer to stay away from anywhere that is rumored to be haunted, had a tragedy occur there, or simply feels creepy to her.

Due to her isolated upbringing within a lab, Laynia's social skills are rather lacking. She's extremely polite, but there are so many ways that one can commit a faux pas even with perfect manners, and the nuances of how to navigate complex personal situations escapes her completely. Of course, this applies to plenty of people who WEREN'T raised in a box, so she's really doing marvelously, considering her background. Overall, she comes off as well-bred but clueless, and many assume her to just be a naive rich girl cliche. Her Russian accent also helps with this, making many people attribute her social missteps as merely due to being foreign. Laynia gladly allows them to think this. During times of high emotion or action, Laynia's social niceties deteriorate further, and it's at these times she's at most risk of hurting others emotionally---which, also, is a time they'll most likely be hurt, if their emotions are also running hot.

Laynia is more than a little bit of a hypocrite with her morals when it comes to violence and killing in the line of duty. For the most part, she'll always use the minimum force needed to accomplish a task, and will resort to lethal means only when it is truly necessary. At least, until it comes to someone she personally cares about being hurt. For instance, she would probably just teleport a group of bank robbers to jail with her Darkforce powers, leaving them unharmed but contained, even if they shot a hostage. But if they shot her brother? Then they would die. Some people might see this as proof of her devotion to her loved ones, and it is, but it also means that she applies special standards to her own pain and loss over others, and loses her morals when they're actually in a position where it's difficult to uphold them. What's worse, she'll actually be downright irrational in these situations; she'd probably not only kill the person actually responsible for consciously choosing to murder her brother directly, but she'd also likely go after the person who sent them on the assignment. Laynia has precious few people close to her, and her mania at the prospect of having them taken away is something both dangerous and easily exploited. Un-hypocritically, she does understand this in others, seeing it as understandable to commit murder in righteous anger, but not in cold blood.

She also understands feelings of isolation, alienation, and being kept apart from others. When she sees someone or something (even an insect) kept prisoner, her instinct and desire is to free it, and she will do so if the being asks, even if it is an enemy.

She is far from blindly loyal, and will question her own side should they do things she doesn't agree with, and is also capable of respecting her enemy and even considering them possibly in the right. Despite having been raised to be obedient first and always, she has always had a strong conscience of her own, to the point that she will refuse to work with someone should their methods be too brutal, or reject a loved one if they commit a heinous act.

That said, she has trouble openly questioning those in positions of authority over her, specifically those of her own country. She is deeply loyal to Russia, and willing to do things she finds distasteful and wrong if it means saving her homeland, such as kidnapping or pressing someone into service. This same loyalty has made it easy for her government to deceive, manipulate, and just plain strongarm her into serving them in ways she finds wrong. Eventually, she is pushed too far and vows to never again serve the Russian government, but she deeply loves Russia itself and seeks to reform it from within, rather than defecting to the US. She’s basically in an abusive relationship with an entire government/country.

Since her only peers growing up were two boys that grew into very proud and aggressive men, it’s made her a bit sexist, tending to generalize men as always thinking they know best and as always fighting first without question.

She believes in battle-forged trust, and will typically consider someone a friend and automatically trustworthy if they fight on the same side together at any point, even if they don’t actually get to know each other at all, and be offended if they don’t think the same of her.

Despite her veneer as the softest member of her squad, Laynia is defiant in the face of torture and captivity—-and as kind as she can reasonably be when she is the captor rather than the captive, which has happened more than once when service to her country required her to commit kidnapping.

Laynia was raised only to be concerned with the physical well-being of herself and her teammates. It would not be accurate to say that she doesn’t care about the feelings of others, more that she just doesn’t always prioritize them as highly as she should. Because of this, she can frequently ignore or tread on the feelings of others, giving the impression she’s insensitive or mean. Ironically Laynia actually considers herself quite sensitive and emotionally astute, and would be very surprised to learn of such complaints against her. This is because growing up, she WAS considered the emotionally wise one—but only compared to her brother and Ursa Major!

Because Laynia was brought up not to complain, she often won’t express that something is bothering her or that someone has offended her. She thinks she’s doing the right thing, but many people would in fact far prefer that she speak up if she’s got a problem.

Laynia lacks a lot of basic life skills because they simply weren’t taught to her in the “school” she was raised in. For instance, what outfits are appropriate where, car maintenance, budgeting, cleaning, and cooking. She was taught how to find and prepare food in the Siberian wilderness should she ever be stranded or stationed there, but not how to go to the supermarket and make a normal meal in a normal kitchen. She knows to turn to Google for most of this stuff, she's not stupid, but it can be surprising to some people what she doesn't know, and she often doesn't even know it's something she needs to know until it comes up.

Laynia is automatically inclined to trust and obey doctors, professors, and similar people, as well as military personnel. It doesn’t mean she’ll do or believe absolutely anything they say, that depends what it is, but she gives their opinion and approval more weight than she does other people.

Laynia has a hard time making big decisions, and an even harder time sticking to them, frequently going back and forth even after she's made her initial choice.

Laynia takes criticism from her superiors very personally, but doesn't show it. Crying every time you get reprimanded of course wasn't something you're allowed to do when being trained by the State, so of course she'd never show it, but she would FEEL it because she was taught that her entire purpose was to serve said State, thus her self-worth hinges on it, and a failure hurts that self-worth. This need for approval from authorities means she’ll try to evade blame when something goes awry, and is loath to step out of line. This can make her a snitch, a suck up, and disliked by her peers for it. Laynia does her best to put up a kind and cordial demeanor to all, and retain a polite decorum even when it’s not returned. This is more to avoid making waves in the team than anything else. If there is discord in the ranks, she refuses to ever be the one to blame for it. It’s not that Laynia doesn’t question orders ever. She does. And she does sometimes find her moral conscience at odds with them. The problem is that she seldom acts on these thoughts, instead proceeding with her missions despite her misgivings.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Review

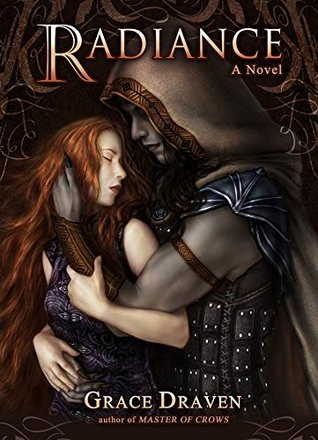

Radiance. By Grace Draven. Self-Published, 2014.

Rating: 2/5 stars

Genre: fantasy romance

Part of a Series? Yes, Wraith Kings #1

Summary: THE PRINCE OF NO VALUE

Brishen Khaskem, prince of the Kai, has lived content as the nonessential spare heir to a throne secured many times over. A trade and political alliance between the human kingdom of Gaur and the Kai kingdom of Bast-Haradis requires that he marry a Gauri woman to seal the treaty. Always a dutiful son, Brishen agrees to the marriage and discovers his bride is as ugly as he expected and more beautiful than he could have imagined.

THE NOBLEWOMAN OF NO IMPORTANCE

Ildiko, niece of the Gauri king, has always known her only worth to the royal family lay in a strategic marriage. Resigned to her fate, she is horrified to learn that her intended groom isn’t just a foreign aristocrat but the younger prince of a people neither familiar nor human. Bound to her new husband, Ildiko will leave behind all she’s known to embrace a man shrouded in darkness but with a soul forged by light.

Two people brought together by the trappings of duty and politics will discover they are destined for each other, even as the powers of a hostile kingdom scheme to tear them apart.

***Full review under the cut.***

Trigger/Content Warnings: sexual content, bullying, violence, blood; references to infanticide, ableism, torture, and incest

Overview: I learned of this book when an artist I follow on tumblr mentioned it as one of their favorites. I had high hopes after seeing so many 4 and 5 star reviews, but unfortunately for me, I wasn’t as enthusiastic as most people seem to be. While I did appreciate that the hero wasn’t a gruff, emotionally damaged, violent man, I personally found the story as a whole to be rather dull. There were way too many scenes that focused on domestic life at the Kai castles, and while that could have been an interesting plot in itself if the stakes were high enough, the political drama wasn’t developed enough to be thrilling, nor was the Kai court different enough from the human one to be a tale about immersing oneself in a new culture. Even looking at this book purely through the lens of romance, I don’t think there was enough there; while I don’t think the hero should have been mean to the heroine or something like that, I do think the relationship could have benefitted from developing a little more, and for Draven to have really dug into the nuances of what changes when a couple moves from friends to lovers. Thus, this book only gets 2 stars from me.

Writing: Draven has a simple writing style that fits well within the romance genre. It flows well and balances telling and showing so that worldbuilding doesn’t feel too info-dumpy. My biggest complaints are things that are easily fixable, like correcting typos and moving flashbacks around so that they occur at more appropriate moments. Other than that, I don’t have too much to say about the writing; it was fine.

Plot: In a way, this book is a Beauty and the Beast retelling: two people must overcome their revulsion to the other’s appearance before they fall in love with the good character underneath. Behind this main plot is a political drama in which several kingdoms are vying for territory, making and breaking alliances while a conniving queen does her best to stay in power.

Regarding the Beauty and the Beast plot, I really liked that Radiance seemed to adhere more closely to the core themes of the original fairy tale than a lot of other retellings I’ve encountered; instead of a story about a woman trying to tame the “bestial” man with her womanly charms, both characters in Draven’s book have to learn to see the other as beautiful by learning to appreciate one another’s culture. The main scenes that come to mind that do this well are the times when Ildiko (our heroine) finds beauty in the Kai death ritual (the mortem light) and when her expectations are subverted when it comes to the food the Kai eat (not the scarpatine, but the other dishes). I also liked that Draven devoted a lot of time to detailing why the Kai found human eyes so off-putting, and Brishen (our hero) comes to appreciate them when learning to read his wife’s emotions. If anything, my main complaint is that I think Draven could have done more to enhance these themes by tweaking her worldbuilding; the Kai were different from humans in a lot of ways, but so much was the same (court politics, social hierarchy, etc.) that I think the task of learning to appreciate a different culture wasn’t difficult enough. I would have liked to see the Kai have a completely different social structure, one that was so alien to the human characters that learning to see the beauty in it proved to be more of a challenge. Because adapting wasn’t too hard and Brishen and Ildiko seemed to have no moments where they suddenly realized they loved rather than just respected or liked the other, I was frequently bored, mostly because there were so many domestic scenes without relationship milestones - instances where Ildiko and Brishen came together as a couple, bonding over things that challenged them to grow as people.

The political plot, in my opinion, was a little ho-hum and wasn’t nearly present enough to be important. We are told that there are rising tensions between three kingdoms, and some people disapprove of the marriage alliance between Brishen and Ildiko, but it kind of felt like a background threat, in part because there were so many scenes depicting feasts (4, by my count) rather than political intrigue, or we get scenes like Ildiko dropping her mother’s necklace in a vat of dye and then Brishen offers to take her to the next town to repair it. Sure, a couple of bandits try to kill Brishen and Ildiko, and some treachery happens later in the book, but the middle section mainly consists of feast scenes, domestic life, or petty drama. I wanted a little more substance to the non-romance plot; perhaps the marriage could have been more explicitly important for the well-being of the Kai kingdom as a whole, and Ildiko has to use her skills to make the Kai more loyal to her. Or, Draven could have gone another route and made the Kai queen to have a clearer political agenda throughout the book other than just being mean to everyone around her. It is mentioned that Brishen and his brother are afraid to cross her in part because magical ability diminishes with each successive generation; maybe that could have been a major focal point or hurdle when plotting against the Queen, rather than an incidental detail that only returns later in the book. Either way, I wanted the politics to be more than just background, and for there to be much higher stakes that will be felt by more people than just Brishen and Ildiko.

Characters: Ildiko, our heroine, is a human woman who enters into an arranged marriage with a Kai prince in order to seal an alliance. I really liked that a lot of the story was centered on Ildiko learning to acclimate to Kai culture and navigate their court politics, and I think it was smart to show that her experience as a courtier in the human kingdom helped her survive the Kai one. I do wish Ildiko’s personal arc had been more about her overcoming her prejudices to appreciate a different culture; while Ildiko isn’t outright racist or resistant to adapting, I do think it would have been more emotionally satisfying if she had clearly entered the marriage with a lot of assumptions about the Kai that turned out to be untrue. If that didn’t sound appealing, maybe Ildiko’s ability to navigate court politics could have been more integral to the plot as a whole, rather than her rather passive role during the final showdown.

Brishen, our hero, was a pleasant surprise; he was kind and considerate, and he didn’t let his power-hungry parents turn him into a gruff, emotionally-unavailable husband. While I did like that he was kind, I also wish his personal arc had been more about overcoming his assumptions about humans or overcoming some other personal conflict, such as balancing his duty to his people/kingdom with his desire to escape the more toxic elements of it. In that regard, I think his romance with Ildiko could have served an interesting purpose: by teaching Ildiko about his culture, he learns to appreciate it more while also finding an escape in her. It would also be cool if he realized that duty doesn’t necessarily mean obeying the monarchs, but doing what’s best for the people.

Supporting characters were a mixed bag. Some, like Brishen’s cousin Anhuset, were interesting but didn’t seem to have a subplot of their own, while others, like Queen Secmet, seemed one-dimensional. In some ways, the one-dimensional characters ensured that most of the focus was on Brishen and Ildiko, but I would have liked a little less feasting and a little more high-stakes conflict that involved these side characters functioning in ways that developed their own arcs.

Romance: Ildiko’s and Brishen’s romance follows a friends-to-lovers arc. When the characters first meet, they instantly bond over their willingness to be honest about their feelings regarding the other’s appearance and culture. I liked that they didn’t start out as completely repulsed by one another, and the friendship bond made for a good safety net when Ildiko has to face the Kai court. I do wish, however, that there had been more explicit developments in showing how the relationship moves from friendship to romantic love. For example, I would have liked scenes where Ildiko has moments of realization regarding what a good man Brishen is, and where Brishen realizes how good a woman his wife is, both in reaction to major plot points (rather than what we get, which is stuff like Ildiko watching Brishen prepare to spar or something). Some of those moments are there in the plot as-is - I’m thinking scenes like when Ildiko learns what an honor it is to have Brishen carry a mortem light for someone beneath his class - but I think there could have been a more defined romance arc.

Worldbuilding: I really liked that Draven didn’t feel the need to overwhelm the reader with worldbuilding details, but I also think she should have done more to make the world feel more purposefully crafted. My biggest problem with Draven’s worldbuilding is that certain elements seemed to be present for no reason at all, or because they were convenient details. For example, the Kai make this very expensive dye called amaranthine, and though we’re told that humans benefit from trading for it, the amaranthine isn’t really involved in an interesting way other than for Ildiko to accidentally stain her skin with in a moment of thoughtlessness. Also, during the last big showdown, we’re randomly told that there are magefinders and a temple which shields the Kai from these magefinders. It felt like these details were inserted for convenience, and I wish more was done to make the setting feel like a character itself.

TL;DR: Radiance does a good job at subverting some expectations, but ultimately doesn’t have a plot that challenges the characters to grow, either individually or as a couple.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lord of the Rings: 6 Games That Brought Middle-earth to Life

http://bit.ly/2Le95WM

From text adventures to MMOs, Lord of the Rings games have never been in short supply. Here are some of the best...

facebook

twitter

google+

tumblr

News

Books

Phil Hayton

Apr 29, 2019

The Lord Of The Rings

There's no shortage of franchises, across the vast world of multimedia entertainment, that have tried to translate their success into a video game tie-in. Look at the huge pile of Star Wars games, for instance, or the sizeable stack of superhero games on the horizon.

While these releases will usually coincide with a blockbuster film or TV series, occasionally we get to experience the magic of our favorite franchises in video game form before Hollywood gets its hands on it. A great example of such a franchise is the work of J.R.R Tolkien, which has enchanted the imaginations of readers since before video games were even a thing.

Today, we are going to journey across six iterations of Lord of the Rings video games, exploring how each title brought Tolkien's vision of Middle-earth into the hands of gamers...

The Tolkien Software Adventure Trilogy

1982 | Commodore 64, ZX Spectrum

While trying to explain text adventures and microcomputers to a modern-day gamer might be a bit like showing a spaniel a card trick, it’s important to look at the humble beginnings of franchise-based video games. Microcomputers such as the Commodore 64 are where it all began for digital Middle-earth, with the release of The Hobbit Sofware Adventure in 1982.

The Hobbit by Beam Software was the first of four titles to be released on microcomputers of the time, with each game covering part of the LOTR saga. As you might expect, fancy visuals and audio have no power here, with the player's imagination and ability to read being the key parts of the experience. If you’re unfamiliar with the text adventure genre, the player is essentially given a description of the scenario that they’re in, which then requires an appropriate command to be typed in response. The best modern-day example of this is the Black Mirror episode "Bandersnatch," which features a similar text adventure, albeit with more psychological trauma.

The Hobbit was followed by another 3 titles by Beam Software: The Fellowship of the Ring, Shadows of Mordor (No, not THAT game), and The Crack of Doom. Each title also included its accompanying paperback novel as an added bonus, which was a fantastic way to introduce new fans of the time to the franchise. Meanwhile, here in 2019, a simple manual with your game is like finding a golden ticket in your chocolate bar.

You may have noticed a heavy emphasis on referring to these titles as software, which is probably wise considering it’s a text adventure. In terms of excitement, these games can’t really hold a candle to the arcade adrenaline rush that was in vogue back in the ’80s. However, this format is a perfect starting point for adapting a beloved work of fantasy into an interactive format, without doing anything silly, like turning it into a spaceship shooter. Despite the only visuals in the game looking like a Microsoft Paint masterpiece, the actual interactive functionality and depth of content within these games were the perfect way to experience Tolkien's fantasy epic at the time.

The Lord of the Rings Vol. 1

1994 | SNES

As we leave behind the horrors of cassette and floppy disk load times and move onto the luxurious world of '90s video games, we also get to experience the birth of LOTR action-adventure games. Produced by Interplay Productions, The Lord of the Rings Vol. 1 is an action RPG for the SNES, which resembles the likes of Secret of Mana.

The graphics weren’t exactly cutting edge and the gameplay itself left a lot to be desired, but in terms of its presentation and atmospheric soundtrack, this was a great start in terms of introducing gamers to Tolkien’s work. Not to mention this game supports four-player co-op via a multitap adapter, which allows players to take on the role of various iconic characters such as Frodo, Samwise, Legolas, and Gimli.

For a game based solely on works of literature, Interplay did a fairly good job of converting it into an action-adventure. The 16-bit world painted in this title does a good job of assisting the imaginations of gamers, who didn’t have much imagery to draw from until the dawn of Peter Jackson’s films.

The Fellowship of the Ring

2002 | PS2, Xbox, PC

Considering that the first New Line Cinema film based on LOTR was released in 2001, you’d assume that the officially licensed game was based on said film, right? Well, no actually, the 2002 Fellowship of the Ring game published by Vivendi Universal is yet another title based solely on the original book.

Featuring an action-adventure style, with a similar feel to the likes of Fable, this title features practically the same story as the first film, with certain sequences having an uncanny similarity. Many great adventure game aspects reside within this adaptation: item collection, puzzles, stealth, and combat all make the experience feel like a true video game translation.

The game’s story itself does do an adequate job of telling the story of Frodo’s departure from The Shire, yet was perhaps at the mercy of being compared to the films, which were ground-breaking for the franchise, after all. Let’s be honest, we know the difference between Ian McKellen and the voice of Professor Utonium from The Powerpuff Girls (No offense to Tom Kane).

For those unaware that this game wasn’t associated with the films, it’s likely that the rich environments and adventure style gameplay gave players a chance to walk merrily across Middle-earth in the bare feet of familiar characters.

The Two Towers/Return of the King

2002 | PS2, Xbox, GC

Despite Vivendi’s LOTR title being released just months before, EA also managed to get their hands on the license, with the added bonus of being able to make games associated to the films. Debuting in 2002, the movie-based titles featured less adventuring and more action, with core aspects of the gameplay being based around wiping out hordes of enemies during movie sequences.

While these games are definitely an effort to immerse players into the films, rather than the books, they still serve as a great way to deliver an interactive version of Middle-earth’s conflicts. Strangely, The Two Towers covers events that took place in the first film, which is perhaps down to the fact that EA couldn’t make a whole game based on that part of the story.

The following title, Return of the King, uses the same mechanics and style established in EA’s first title, which proved to be popular. Luckily, the series managed to avoid the stigma associated with movie games (i.e. that they're cash grabs), with legitimately fun gameplay and a respectful translation of the original story.

The Hobbit

2003 | PS2, GC

It may have taken until 2012 to finally get a film adaptation of the first part of Tolkien’s epic fantasy, yet this didn’t stop our old friends Vivendi Universal from taking matters into their own hands. Even though Vivendi first Middle-earth title failed to make the impact it desired, Inevitable Entertainment teamed up with Vivendi to create The Hobbit in action-adventure form.

This cutesy adventure featuring Bilbo Baggins bears a resemblance to The Fellowship of the Ring, with some slight changes, such as a more light-hearted aesthetic, faster movement, and a more fluid approach to combat. The developers also took some liberties with the dialogue and voice acting, being more confident in their approach, rather than repeating the first game's attempt to sound like the movie actors.

It’s easy to compare action-adventure titles like The Hobbit to others in the genre, but for what it's worth, this game is an amazing way to experience Tolkien’s fantasy prelude. With its colorful environments, quirky characters, and enjoyable gameplay, The Hobbit is a refreshing way to delve into the story of The Lonely Mountain without having to endure unsettling CGI.

The Lord of the Rings Online

2007 | PC

Most major movie franchises have tried their hands at MMO titles. While many of these attempts have failed to capture the success of juggernauts like World of Warcraft, with Lord of the Rings Online, a combination of a beloved world and a dedicated fanbase has managed to keep the game alive since its release in 2007.

The game features many of the MMO tropes that you’re familiar with, yet it puts emphasis on placing the player into the shoes of a citizen of Middle-earth during the third age, which matches up to the events of the novels. Unlike a lot of MMO and sandbox games, LOTR Online draws its attraction from having rich lore and landscapes that have already been established, which does well for attracting new players. The fact that this game is also now free to play means that players can experience a big portion of Middle-earth without the need to splash out.

There are numerous games that we haven't mentioned among these six key titles, and honorable mentions should go to the LEGO-themed games and the likes of Shadow of Mordor. Certainly, gamers aren't short of access to one of the best fantasy stories ever told. And with the recent announcement of Daedalic Entertainment's action-adventure game about Gollum, we can be sure that Middle-earth will stay in the palms of gamers for many years to come...

from Books http://bit.ly/2VGcstT

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Post R. Collated Quotes

Style:

Jim Jarmusch: “A career overview? I’m not a ‘big looking’ back guy, but I’ll do my best. I don’t even watch my films. Once I’m done with them they’re gone for me.” (Post E)

GA: “ It is entirely made up of discreet shots - every scene consists of one shot interrupted by black film - which is quite a formal or experimental way of telling the story. Why did you decide to do it and what is your interest in those formal things?’’ Jim Jarmusch: “I think it comes from really liking literary forms.” (Post G)

Jim Jarmusch: “The intention was to shoot short films that can exist as shorts independently, but when I put them all together, there are things that echo through them like the dialogue repeats; the situation is always the same, the way they’re shot is very simple and the same - I have a master shot, if there’s two characters, a two shot, singles on each, and an over-the-table overhead shot which I can use to edit their dialogue.So they’re very simple and because the design of how they’re shot is worked out already, it gives complete freedom to play; they’re like cartoons almost to me. And it’s a relief from making a feature film where everything has to be more carefully mapped out. So I like doing them and they’re ridiculous and the actors can improvise a lot, and they don’t have to be really realistic characters that hit a very specific tone as in a feature film. They’re really fun, I want to make more of them definitely. Sometime I will release them all together, but I don’t know when.’’ (Post G)

“I’m talking about a very particular, all too common response to his work – usually from fans, though also in some cases from detractors. It’s the notion that the main thing to say – indeed, perhaps the only thing to say – about Jarmusch and his films is that they are ‘cool’.” (Post I)

Peter Keogh “ You’re often referred to as a minimalist. Do you agree with that label?”Jim Jarmusch: “I think of minimalist as a label stuck on certain visual artists. But I don’t really feel associated with them.”Peter Keogh: “There are also literary minimalists - Raymond Carver, Anne Beaty”Jim Jarmusch: “I think maybe what they’re saying is that the films are very light on plot and therefore minimal stylistically as well. My style is certainly not Byzantine or florid or elaborate. It’s pretty simple. Reduced.” (Post J)

“Jarmusch can’t be easily pinned down to any cinematic wave or category. “I don’t know where I fit in. I don’t feel tied to my time.”He is certainly not on the same time scheme as the rest of cinema, or indeed, the rest of humanity – which is perhaps why Only Lovers Left Alive is one of several of his films, including Night on Earth and Mystery Train, to take place after dark. Tilda Swinton has said: “Jim is pretty much nocturnal, so the nightscape is pretty much his palette. There’s something about things glowing in the darkness that feels to me really Jim Jarmusch. He’s a rock star.” (Post K)

“As a director, too, there are recurring elements: a minimalist aesthetic, laconic but lovable characters (often played by musicians), a cool compositional remove that invites humour without sacrificing sincerity.” (Post L)

“The second premise of auteur theory is the distinguishable personality of the director as a criterion of value. Over a group of films, a director must exhibit certain recurrent characteristics of style, which serve as his signature. The way a film looks and moves should have some relationship to the way a director thinks and feels.” (Post M)

“…postmodernism reevaluates tradition and openly plays with its rich heritage, often in the form of pastiche.” (Post N)

“…modern American independent film,with Jarmusch as one of its leading representatives, presents us with stories that disrupt the clear unified and causal structure of Hollywood films, thus resembling the pattern of Lyotard’s “little narratives” . While Hollywood films fall into specific genres and strictly adhere to its conventions, the leading representatives of the modern American independent cinema (Jarmusch, Hal Hartley, Quentin Tarantino, the Coen brothers, David Lynch) breakup the generic structures, overthrowing the need for closure, one of the main characteristics of classic Hollywood. The temporal structure is distorted, as can be seen in Mystery Train or Pulp Fiction, while the focus of the films is not on the active, goal-oriented protagonist, but on the people from the fringes of society, outsiders who oppose the accepted social norms.” (Post N)

“The underlying tendency of Hollywood films is to present the world as ultimately presentable and knowable, but a more thorough analysis reveals the realism as only partly rooted and clearly distorting external reality. Mark Cousins labels the Hollywood style closed romantic realism, emphasizing the fact that actors seem to live in a parallel universe (494). Emotions are heightened, main characters idealized and able to over come any obstacle. Although presenting a parallel universe, Hollywood tries to create an illusion that the events shown on the screen correspond to the world around us, thus creating a falsified reality.” (Post N)

“Foucault’s and Baudrillard’s analyses are even more detailed, providing the useful concepts of hyperrealism and simulation. Illustrating his concept of the third-order image, Foucault claims that “Disney land is presented as imaginary in order to make us believe that the rest is real, when in fact all of Los Angeles and the America surrounding it are no longer real, but of the order of the hyperreal” (Post N)

“The concept of time has similarly been disrupted. Hollywood has always concentrated on kairos, the significant time, while completely abandoning the presentation of chronos, the ordinary time. The difference between these two concepts summarizes the inherent difference between Hollywood and the modern American independent film. While Hollywood has concentrated on action and dramatic aspects of storytelling, modern American independent films have explored the moments in-between, the events devoid of dramatic tension, which explains why Jarmusch chose not to present the most dramatic element in Down by Law, when the three cellmates escaped from prison.” (Post N)

“His second feature Stranger than Paradise, gloriously shot by Tom DiCillo in black and white cinematography, is divided into three parts and separated by fade-outs, whose function is to destroy the illusory nature of the Hollywood invisible style.The post-industrial and scapes of modern America are similar to those in Tarr’s Satantango , providing an anticipatory cultural link. The main protagonists come from Europe, which plays a vital role in many Jarmusch’s films, signifying the impact of the Other.” (Post N)

“All of this transpires at a pace that may admittedly prove frustrating for some viewers, but for me Only Lovers Left Alive it as its best during such sequences; in fact, it enters far more problematic territory precisely when it deviates from this rhythm.” (Post O)

“It also points to another significant aspect of the film, which is its use of music; this includes original contributions from Jarmusch’s own band SQÜRL, and a diverse list of other artists and tracks (including Charlie Feathers’s rockabilly classic ‘Can’t Hardly Stand It’). The music within the film functions as a soundtrack to persistent musings about the nature of art and the artist, and their resilience (or otherwise) with the passing of time” (Post O)

“In the end, Only Lovers Left Alive is exactly what you’d expect from a Jim Jarmusch vampire film: meditative and unhurried, wryly humorous and culturally allusive — and utterly beguiling. In fact, it turns out that the vampire makes for a curiously appropriate Jarmuschian figure, isolated and out-of-time. Its pair of undead lovers may have (quite literally) seen it all before, but they’ve ultimately provided a fresh take on the vampire genre.” (Post O)

Themes:

Jim Jarmusch: “Adam and Eve are sort of outside type characters, bohemian types, and they probably already were hundreds of years ago. They’re not exactly a representing the square world to start with. They’re kind of eternal. I hate the word ‘hipsters’, but they are certainly on the outsider’s side” (Post E)

“I guess most of my films are road movies’’ (Post E)

“His characters tend to be losers, drifters and strays.’’…’’His films are about communication, or crippled communication. People who love each other (or who will grow to love each other), but who can’t talk to each other. Often, foreigners can communicate more easily than fellow Americans, despite the language barrier.’’ (Post F)

“GA: The film has certainly got a serious side to it, but it is also very full of humour and that’s something that’s coursed through all of your work. Why is an element of comedy so important to you in your movies? JJ: Laughter is good for your spirit’’ (Post G)

“Nearly all of Jim Jarmusch’s 12 feature films to date are centred around a leading man, often playing a character in the midst of an existential crisis, whose sentiments and actions come to define the spirit of the movie.’’ (Post H)

“Now, it’s true that filmgoers hadn’t seen many movie protagonists like the slightly lazy, generally unremarkable Willie” (Post I)

“Time and again, Jarmusch seems to be telling us that love, friendship, respect for others, and an open, imaginative mind are key to answering that question.” (Post I)

“What fascinates Jarmusch in the vampire myth is less the usual blood-guzzling, though there’s plenty of that, than the educational opportunities afforded by supernaturally extended life.” (Post K)

“His films consistently flout the conventions of American screen storytelling. For one thing, their subjects are not always primarily American, and Jarmusch often shows the US from the perspective of foreign visitors: Italian, Hungarian, Japanese.” (Post K)

“The director’s seriousness is often underestimated, says New York critic and festival director Kent Jones: “There’s been an overemphasis on the hipness factor – and a lack of emphasis on his incredible attachment to the idea of celebrating poetry and culture. You can complain about the pretentiousness of a lot of his movies, [but] they are unapologetically standing up for poetry. [His attitude is] ‘if you want to call me an elitist, go ahead, I don’t care’.” (Post K)

“It’s hard not to see the theatrically suicidal Adam as Jarmusch in disguise, the director’s neuroses in almost human form.” (Post L)

“The third and ultimate premise of the auteur theory is concerned with interior meaning, the ultimate glory of the cinema as an art. Interior meaning is exploited from the tension between a director’s personality and his material…It is not quite the vision of the world a director projects nor quite his attitude toward life. It is ambiguous, in any literary sense, because part of it is imbedded in the stuff of cinema and cannot be rendered in non cinematic terms.” (Post M)

“Only Lovers Left Alive is Jim Jarmusch’s latest foray into genre filmmaking, after the equally idiosyncratic ‘psychedelic Western’ Dead Man (1995) and urban Samurai thriller Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai (1999), and casts the vampire as a typically offbeat, world-weary Jarmuschian outsider.” (Post O)

“Shot for shot, Only Lovers Left Alive is visually stunning, and nothing embodies this more than the sight of Adam and Eve standing back-to-back, his black hair and clothes contrasting with her platinum hair and white clothing, as they gaze up at the former glory of the Michigan Theatre.” (Post O)

“With unassuming casualness, Jarmusch’s soundtracks and cast lists have created a cumulative portrait of the US musical underclass, much of it African American, that reflects his films’ interest in the marginal or overlooked – the drifters, dreamers and beatniks who give that troubled nation its artistic character.” (Post P)

Collaborators:

“Joie Lee, the actress who features in one of the early Coffee And Cigarettes shorts, says Jarmusch is the only film-maker she knows who owns his own films. “Very few directors own their own films - Spike [her brother Spike Lee] doesn’t even own his own films. This pretty much puts Jim in a league of his own. What it means is that he doesn’t have to do things for the studio - he’s autonomous and can realise his artistic vision."’’ (Post F)

“‘’Right!’’ says the Coffee and Cigarettes cinematographer, Fred Elmes. ‘’He always asks my advice, collects the information and then makes the decision himself’’’’ (Post F)

Jim Jarmusch: “I’m not a director who says, “Say your line, hit your mark”, that’s not my style. I want them to work with me and everyone I choose to collaborate with elevates our work above what I could imagine on my own. Hopefully, if not it’s not working right. I’m like a navigator and I try to encourage our collaboration and find the best way that will produce fruit.” (Post G)

“The multi talented John Lurie worked on Jarmusch’s first three films as both actor and composer.” (Post H)

“Hiddleston presents viewers with a character who retains a small inkling of affection for the world, but his own skepticism has become an infectious poison” (Post H)

“It may indeed have at least something to do with Jarmusch’s good looks and his musician friends, but it may also be a consequence of the fact that he first caught the attention of many filmgoers (after his 1980 debut Permanent Vacation) with Stranger than Paradise, in which the protagonist, Willie – played by John Lurie of the Lounge Lizards – might be seen as someone at least trying to appear ‘cool’. Willie is keen to conceal his Hungarian roots (not to mention his Hungarian name), reluctant to play host to his visiting Hungarian cousin, and generally appears happiest with a way of life that’s fairly solitary, slacker-like and self-centred, save for his friendship with the more outgoing Eddie (Richard Edson).” (Post I)

Jim Jarmusch: “Usually I write for specific actors and have an idea of a character. I want to collaborate with them on. The story is suggested by those characters.” (Post J)

Jim Jarmusch: “We do a lot of improvisation in the rehearsal process”…”Then while we’re shooting, how much improvising we do depends on the actors. Obviously I prefer to improvise in rehearsals because you’re not burning money. But some actors need a longer leash.” (Post J)

“The more Hiddleston and Swinton share the screen, the better, because the film lives and breathes through their elegant interactions with one another, and in many ways it presents a portrait of a relationship that is as intimate and low-key as Richard Linklater’s triptych of films Before Sunrise (1995), Before Sunset (2004), and Before Midnight (2013) — just with more blood-drinking.” (Post O)

“The version of Detroit that is featured in the film is shot through a lens that implies it is the ideal landscape both to engender and reflect Adam’s ennui. In this, it clearly recalls the work of Yves Marchand and Romain Meffre in their hauntingly beautiful photography series ‘The Ruins of Detroit’, and the film as a whole boasts similarly striking cinematography by Yorick Le Saux (collaborating with Jarmusch for the first time” (Post O)

“From the start, he used musicians as actors and looked to music to provide the animating vitality that he resisted visually. Songs say what his characters cannot. Screamin’ Jay Hawkins’s throat-abrading scorcher I Put a Spell on You blasts from a tinpot cassette player in Stranger Than Paradise, in which the characters scarcely do more than grunt and glare. That film starred the stringbean-thin, cucumber-cool jazz saxophonist John Lurie alongside Richard Edson, the original drummer from Sonic Youth. It made Jarmusch’s reputation in 1984, back when “indie” really did mean “independent” rather than “the boutique arm of a major studio”. (Post M)

“You could assemble a musical supergroup from his casts since then. Lurie and Tom Waits sashayed through New Orleans in Down By Law, with Waits going on to score Night on Earth. Screamin’ Jay Hawkins played a hotel concierge in a spiffy tomato-red suit in Mystery Train; Joe Strummer and the ghost of Elvis also had walk-on parts. Iggy Pop (the subject of Jarmusch’s recent documentary Gimme Danger) showed up as a trapper in a bonnet in Dead Man, and the White Stripes discussed Nikolai Tesla in Coffee and Cigarettes, where RZA and GZA, both of the Wu-Tang Clan, could also be found knocking back the joe with Bill Murray. The RZA also lopes down the street in Ghost Dog: Way of the Samurai, a Jarmusch film he scored. (Post P)

Auteurism:

Jim Jarmusch: “A career overview? I’m not a ‘big looking’ back guy, but I’ll do my best. I don’t even watch my films. Once I’m done with them they’re gone for me.” (Post E)

Jim Jarmusch: “I don’t read good reviews of my films, I love negative ones. Maybe it’s a little masochism, but more of a matter of, ‘’What do they think? They must be very different to me…’’ (Post E)

“Is he a control freak? Yes and no, he says. He loves to work as a team, but ultimately he makes every decision. "Every tiny detail of a film - the design of a cup on a table, all that. I have the ability to create that world, so I’m very fanatical about it. My films are made by hand. I write the script, I’m there to get the financing, and I put together the whole crew and production. All my films are produced through my own company, then I am in the editing room every day, then I’m in the lab, then I’m out promoting the film, so that’s about three years’ work for each film.” (Post F)

Peter Keogh “Since ‘Stranger Than Paradise’ your sensibility and style seem to be dominant in American independent film-making, and also in film-making around the world, such as the Kaurismaki brothers. How do you account for it?Jim Jarmusch “It’s hard to respond to that. I don’t know if my early films have influenced those people or wether it’s a simultaneous reaction to things being glossy and quick cut.” (Post J)

“Of his generation of US independents, Jarmusch has stayed the course, and stayed weird, while others fell by the wayside (Hal Hartley) or learned to work with the mainstream (Spike Lee, the Coens).” (Post K)

“Another thing that makes Jarmusch distinctive is his genuine independence: he is extremely rare in that he has made a policy of keeping control of his own negatives. But his refusal to play the industry game has not made things easy for him. When Harvey Weinstein pressed Jarmusch to cut his 1995 western Dead Man, the director stuck to his guns – later claiming that his refusal had resulted in the film being half-heartedly promoted on release.” (Post K)

“Jarmusch’s unique sensibility doesn’t always appeal to the market. It took seven years to finance Only Lovers Left Alive, with the film finding no takers in the US. In the end, the project was adopted by European producers, Reinhard Brundig in Germany and British veteran Jeremy Thomas. Thomas sees individualists like Jarmusch as an endangered species. "He’s one of the great American independent film-makers – he’s the last of the line. People are not coming through like that any more,” he said.” (Post K)

“Auteur theory is, unsurprisingly, anathema. “I put 'A film by’ as a protection of my rights, but I don’t really believe it. It’s important for me to have a final cut, and I do for every film. So I’m in the editing room every day, I’m the navigator of the ship, but I’m not the captain, I can’t do it without everyone’s equally valuable input. For me it’s phases where I’m very solitary, writing, and then I’m preparing, getting the money, and then I’m with the crew and on a ship and it’s amazing and exhausting and exhilarating, and then I’m alone with the editor again … I’ve said it before, it’s like seduction, wild sex, and then pregnancy in the editing room. That’s how it feels for me.”

I tell Jarmusch that I always likened the process to preparing a meal. I see pre-production as listing the ingredients, production as shopping for them, and the pivotal step of post-production as the actual cooking. Jarmusch thinks this over for a moment, his eyes falling back to his empty plate. He stands, abruptly, and extends a big hand beneath a bigger smile: “Cooking is good too, but I prefer sex.” (Post L)

“I will give the Cahiers critics full credit for the original formulation of an idea that reshaped my thinking on the cinema.” (Post M)

“The three premises of auteur theory may be visualised as three concentric circles: the outer circle as technique; the middle circle, personal style; and the inner circle, interior meaning” (Post M)

“…the first premise of auteur theory is the technical competence of a director as a criterion of value. A badly directed or an undirected film has no importance in a critical scale of values, but one can make interesting conversation about the subject, the script, the acting, the color, the photography, the editing, the music, the costumes, the decor, and so forth.” (Post P)

“This creates the illusion that the music is emanating from inside that footage, which feels exactly right. Jarmusch came to prominence in the early 80s, when movies were first being used as tools to sell soundtrack albums, but his were different. Music wasn’t there to shift units; it lived in the fibres of the celluloid.” (Post P)

0 notes

Text

Lesley Henderson & Simon Carter, Doctors in space (ships): biomedical uncertainties and medical authority in imagined futures, 42 Med Humanit 277 (2016)

Abstract

There has been considerable interest in images of medicine in popular science fiction and in representations of doctors in television fiction. Surprisingly little attention has been paid to doctors administering space medicine in science fiction. This article redresses this gap. We analyse the evolving figure of ‘the doctor’ in different popular science fiction television series. Building upon debates within Medical Sociology, Cultural Studies and Media Studies we argue that the figure of ‘the doctor’ is discursively deployed to act as the moral compass at the centre of the programme narrative. Our analysis highlights that the qualities, norms and ethics represented by doctors in space (ships) are intertwined with issues of gender equality, speciesism and posthuman ethics. We explore the signifying practices and political articulations that are played out through these cultural imaginaries. For example, the ways in which ‘the simple country doctor’ is deployed to help establish hegemonic formations concerning potentially destabilising technoscientific futures involving alternative sexualities, or military dystopia. Doctors mostly function to provide the ethical point of narrative stability within a world in flux, referencing a nostalgia for the traditional, attentive, humanistic family physician. The science fiction doctor facilitates the personalisation of technological change and thus becomes a useful conduit through which societal fears and anxieties concerning medicine, bioethics and morality in a ‘post 9/11’ world can be expressed and explored.

Introduction

In his inaugural speech Dr Robert Wah, President of the American Medical Association (AMA), named Star Trek's iconic physician Leonard ‘Bones' McCoy as his favourite fictional character. In his view, McCoy embodied the qualities of an exceptional leader. He was willing to collaborate to solve problems and to question decisions from a scientific perspective while acting as an advocate for health. Wah explained that “Bones bridged the gaps between the extremes of logic and instinct, rules and regulation, scientific knowledge and human compassion”.1

There has been considerable interest in how doctors are represented in fictional television2–4 and significant research concerning how medicine and medical devices are used in science fiction futures,5–7yet little research to date examines doctors administering space medicine in science fiction.i This is surprising as cultural images of medical professionals have long been considered vital to sustaining the power of institutional medicine.8 Furthermore, the science fiction genre offers important spaces for valuable debates concerning medicine, technoscience and the ethical implications or social uses of biomedicine. We argue that the ‘space doctor’ personalises societal fears and anxieties concerning diverse social issues, including gender and diversity, ethics of surveillance and authority as well as medical enhancement and posthuman futures. Drawing on debates within Medical Sociology and Cultural Studies this article explores how the qualities, norms and ethics represented by doctors in space (ships) are intertwined with issues of gender equality, speciesism and posthuman ethics. Analysis of fictional media stories here starts from the principle that the production of meaning or signification within the narrative is itself a specific practice rather than a mere reflection of reality. The focus of analysis is on the way that narrative discourses become a field in which political and cultural articulations are played out in an attempt to establish hegemonic formations.9

Medical drama continues to occupy an extraordinary position in contemporary television with early series such as Dr Finlay's Casebook (1962–1971) and Dr Kildare (1961–1966) establishing the enduring role of the fictional doctor. Around the same time the character of the ‘space doctor’ became firmly fixed in television science fiction. Indeed, some of science fiction's most memorable characters have been medical doctors, and it could be argued that the character is now an essential ingredient of the genre. But what are the specificities of television science fiction rather than other forms of fictional drama? Perhaps the first, and most obvious, theme of science fiction is claims about futures. All fictional forms exist within an arena of cultural relationships that are historically specific, but science fiction, in both its utopian and dystopian forms, uses narratives to project visions of the future in order to disrupt the present—to remind us ‘that the future was not going to be what respectable people imagined’.10 This leads to a second, and related theme, found in science fiction that presumes that these narrative futures are the result of scientific gadgetry and sociotechnical change. Science fiction often seamlessly combines potential scientific or technological innovation with pseudoscience and pseudotechnology. Yet the important issue for analysis is not realism, but rather is a close reading of what the sign ‘science’ or ‘technology’ is attempting to constitute in the narrative—in this case, what is the use of medical technoscience trying to signify? The final theme, as argued by Suvin, is the Brechtian idea of ‘estrangement’ (verfremdungseffekt) that distinguishes science fiction from myth and fantasy. Myth and fantasy often see human relationships as fixed or supernaturally determined, whereas science fiction focuses on the variable future and problematises human relationships to explore where they may lead in the future. As a representation it ‘estranges… (allowing) us to recognise its subject, but at the same time making it seem unfamiliar’.11 In this paper our analysis draws on these themes to argue that the figure of ‘the doctor’ is discursively deployed to deliver medical care and frequently acts as a moral compass at the centre of the programme narrative—a conduit through which societal anxieties about the futures of health, sociotechnical change, bioethics and medical science can be expressed and explored.

A simple country doctor (in space)

Star Trek constitutes a self-contained subgenre within science fiction.12 The tremendous influence of Star Trek on the science fiction genre coupled with the global reach of the show means that we focus on this particular franchise in detail.ii The creator of the show Gene Roddenberry was a humanist, and it was originally intended to have a progressive political agenda, using the genre to tackle contemporary social issues in an enlightened way, though this aim was concealed from the networks at the time.13 The role of doctor has been a consistent feature throughout all the ‘Trek’ franchises with each recreation of the physician being distinctive and mirroring key aspects of the position of medicine in the era in which it was created. The first and best known of the regular Trek doctors from ‘Star Trek: the Original Series’ (ST:TOS1966–1969) was Leonard “Bones” McCoy, an idealised General Practitioner with a broad skill range, willing to carry out any procedure. While McCoy regularly used advanced medical technology he was also depicted as being uneasy with some aspects of space living and famously had a phobia about using the ship's matter transporters. He was characterised as becoming easily annoyed yet provided a friendly bedside manner. McCoy was frequently the moral centre of the original series and often argued with the unemotional and utilitarian Vulcan Science Officer, Mr Spock.

Early in the series, McCoy describes himself as a ‘simple country doctor’, undoubtedly a reference to the classic W Eugene Smith photo essay for LIFE magazine, ‘Country Doctor’ published in 1948.14 This influential photo essay helped to mythologise the idea of the community-based physician.iii LIFEresearched a suitably attractive location and selected an appropriate doctor, Ernest Ceriani, who was chosen partly for his looks and youth.15 Smith's study painted an evocative picture of a hardworking, emotionally drained physician firmly embedded with his patients in the rituals of rural community life. Like McCoy, Dr Ceriani is shown carrying out a wide range of activities—making house calls, talking to patients and conducting operations in surgical gowns. He also bore a more than passing physical resemblance to Dr McCoy. Both the LIFE photos and ST:TOS's Dr McCoy can be read politically in different and somewhat opposing ways. At the time of LIFE's publication, there was considerable debate in the USA about the introduction of compulsory health insurance to increase the number of doctors serving local communities. This was vehemently opposed by the AMA, and the political intentions of the photo essay were to provide a strong counterpoint to debates about US national healthcare or ‘socialised medicine’.15The pictures contrast Dr Ceriani striding across agricultural fields to make house calls, with him dressed in a surgical gown in a hospital operating theatre. The lone doctor was thus represented as both traditional and modern. This juxtaposition implies that additional physicians, funded by compulsory insurance, were not needed—a single community doctor could do it all. Yet politically Smith, a lifelong liberal, was at variance with the magazine's political intentions for the photo essay. The authentic depictions of medical failure and Ceriani's frozen exhausted stare undermine any message that implies America might not require more doctors.

Similarly, the fictional Dr McCoy presents audiences with a figure that is both traditional and modern. He exhibits some distinctly premodern beliefs about natura medica and the natural healing powers of the body while being comfortable with 23rd-century medical technology. The recurring motif here is the way in which McCoy carries out diagnoses. The Star Trek clinic is shown to contain numerous ‘gadgets’, including the medical tricorder, a non-invasive medical scanner. While McCoy almost always starts his diagnosis by using his tricorder, he is shown throughout ST:TOS using an older and more traditional diagnostic technique—that of palpation, the method of feeling with fingers and hands during a physical examination. For example, in ‘The Deadly Years’ (ST:TOS) a mysterious malady causes some crew members, including Captain Kirk, to undergo extreme ageing. During an examination, McCoy initially uses the tricorder on Kirk's body but concludes his diagnosis by making physical contact using fingers to manipulate his patient's joints. It is only after this material connection that he finds Kirk is suffering from advanced arthritis. In, ‘The Enemy Within’ (ST:TOS), the futuristic technology of the ‘matter transporter’ provides a plot device to explore good and evil in the human mind. A malfunction in the transporter causes Kirk to split into two (‘evil Kirk’ characterised by hostility, lust and violence and ‘good Kirk’ who embodies compassion, love and tenderness). When ‘good Kirk’, expresses revulsion that his evil doppelganger came from within himself it is McCoy who dispenses simple psychological advice about the human condition. He tells a troubled Captain Kirk that ‘we all have our darker side. We need it! It's half of what we are. It's not really ugly. It's Human’ (ST:TOS: ‘The Enemy Within’).

The role of McCoy in ST:TOS has to be understood in the context of other popular medical drama which emerged during this period. The portrayal of fictional doctors was being established in television series such as Dr Finlay's Casebook (1962–1971), Dr Kildare, (1961–1966) Ben Casey (1961–1966) and Marcus Welby MD (1969–1976). Story themes emphasised the dedicated doctor willing to move beyond their professional boundaries to help their patients, motivated not by financial reward but by a noble calling.16Each series centred on the medical hero who was concerned with the lives of their patients, sometimes to their own personal detriment. Many received an official ‘stamp of approval’ from The AMA Advisory Committee or the American Academy of Family Physicians. At this time medicine was becoming more reliant on high-technology science, which dramatically improved treatment and raised its cost, with severe consequences for patient-doctor relations in the USA:

As physicians' incomes rapidly increased, and the profession fought to preserve traditional fee-for-service medicine, many viewed the profession as avaricious and uninterested in public health.17

In other areas of the mass media and academic medical sociology18–21 the flaws in the medical establishment were being very clearly illuminated with critical accounts of medical negligence and lawsuits, rising healthcare costs, and patronising doctor-patient relations. Little of this was depicted in medical drama. Television audiences were captivated by these nostalgic cultural representations which embodied the type of doctors they desired rather than ones who bore a resemblance to their actual healthcare professionals. The television doctors were infallible, had endless time to spend with few patients and were not financially motivated.

The more rushed real-life doctors become, the more leisurely the pace of their fictional counterparts. And the same went for money: as American medicine became increasingly profit orientated, with tales of impecunious patients being turned away from casualty, American medical dramas depicted a medical practice where fees were almost never discussed, and patients never rejected because of their inability to pay.22

Setting an entire series in space facilitates significant creative freedom regarding representing the positive aspects of medicine where doctors have infinite time to care for patients and are untroubled by concerns about funding or payment. Turow argues that this utopian view of healthcare began a trajectory of medical drama in which audiences assume that healthcare is a limitless resource.4 In ST:TOS McCoy never needs to engage with financing problems. His role depicts a future in which futuristic technoscience and gadgetry has a medical role that complements the more traditional and idealistic functions of the physician. McCoy still has time to provide reassuring psychological advice to his patients and carry out physical examinations manually. Also, it is the futuristic technology in ST:TOS that often provides the defamiliarisation effect in the narrative, such as transporters splitting characters into evil and good dyads. McCoy then comes to stabilise and provides a counterpoint to narrative disruption by using time-honoured traditional medical techniques—those of the ‘simple country doctor’.

The female physician: empathy, sexualities, gender and bodies

Themes of estrangement and the problematising of human relationships dominate storylines involving female physicians in science fiction television. These self-confident female characters provide a crucial counterpoint to the first male-dominated medical dramas and to a wider media responsible for ‘the symbolic annihilation of women’.23 As a strong leading character in British series ‘Space 1999’ (1975–1977) Dr Helena Russell conforms to the theme of dedicated and independent physician. As with Dr Janet Fraiser, Chief Medical Officer in Stargate SG1 (1997–2007), Dr Russell could overrule the typical hierarchy of the military setting on the basis of medical authority and defended the ideals of medical ethics against the demands of military necessity. Significantly, within Star Trek: The Next Generation (ST:TNG) there is a gender-integrated crew. However, the two lead female characters are both healthcare related: Dr Beverly Crusher, the Chief Medical Officer and Deanna Troi, the ship's therapist. This shift from ST:TOS, where the most senior female was iconic communication officer Nyota Uhura, is significant and reflects more general debates which featured in the 1980s media concerning gender equality. These characters clearly represent some sort of progress regarding positive depictions of women in primetime television. However, as with Fraiser and Russell, both mainly reproduce traits (culturally constructed) which tend to be attached to women in fictional media.24 They possess skills associated with a constructed ‘femininity’ such as, sensitivity, perception and intuition. Both are at times preoccupied with concerns about their personal lives.25 Thus Deanna Troi is an extreme example of this constructed ‘femininity’ with ‘female’ medical abilities—she is a half-human, half-Betazoid empath who can telepathically read emotions and judge whether an individual is attempting deception or subterfuge.

At a time when debates were circulating concerning gender equality, Dr Crusher's character appeared to be designed as the fantasy woman. She is the most senior female officer in the Enterprise crew, leads a medical team and is a close confidante of the Captain. Crusher is also a single mother who occasionally also takes command of the starship. Crusher exhibits an extraordinary competence that borders on infallibility. ‘She is in all respects a superwoman’.26 Like McCoy before, Crusher's character has had an undoubted positive influence with material consequences beyond the show. One female medical student recalled ‘I think Dr Crusher had a real impact on my formative years—a woman physician who was strong, smart, and respected, who the guys went to when they didn't have the answers’.27

The role of female physician also provides opportunities to explore the ways in which science fiction television facilitates disruptions along the lines of gender and sexuality that would appear to challenge the heteronormativity of television drama and the media of the time. The ability for science fiction to offer provocative possibilities concerning sexuality and female power is coupled with the potential to disrupt traditional assumptions concerning gender, sexuality and bodies. However, such depictions are often limited by the prevailing sociocultural mores. In a ground-breaking episode which explores the complexities of sexuality, Crusher falls in love with a Trill ambassador, Odan (‘The Host’, ST:TNG). The Trill are a symbiotic species with the ability to bond with host bodies. After Odan is fatally injured he temporarily transfers his identity to a male Starfleet officer's body, William T Riker. Crusher is a close friend of Riker and initially struggles with this transition but eventually continues a sexual relationship. The ethical consequences of Riker providing a body, used for sexual purposes by his close colleague, were only hinted at in the narrative. However, when a woman arrives as Odan's permanent host, Crusher rejects her saying ‘perhaps it is a human failing; but we are not accustomed to these kinds of changes’. This exploration of transgender issues and ultimate rejection by Crusher on the grounds of universalism drew mixed responses from ‘Gaylaxians’iv who felt the episode embodied the ideological limitations of the show. It seems to imply that sexual relations with someone as they go through a gender transition are impossible, even in the 23rd century.28

Beyond human: identity, difference and diversity

Discussions concerning the fluid and unstable nature of identity were often reflected in the representations of doctors in science fiction that followed, with gender and sexuality being common themes. In particular, debates about intersectionality opened up the possibilities of subject positions being multiple and relational.29 For example, Doctor Phlox from ‘Star Trek: Enterprise’ (ST:ENT 2001–2005) is the alien (Denobulan) Chief Medical Officer on Enterprise—he is part of an ‘Interspecies Medical Exchange’. As well as being a fully trained Doctor he holds six degrees in interspecies veterinary medicine and is an advocate of a species-spanning approach to healthcare. He maintains a menagerie of plants and animals in the sick bay which he uses to prepare therapies to complement his traditional pharmaceuticals. Hence, as a multicultural physician of the future he is relaxed with technology and is able to draw on alternative healing methods—‘Dr. Phlox reflects the swelling backlash against failed technologies that presently lead so many to experiment with non-traditional or “natural” remedies’.26

In this prequel to ST:TOS his attitudes are contrasted with those of his fellow crew members and he maintains an open and positive stance on diversity (species and cultures). In ‘A Night in Sickbay’ (ST:ENT), the primary focus is on Captain Archer's companion animal, a dog named ‘Porthos’, who has been severely taken ill. But a subplot involves increasing tensions between Captain Archer and his female Vulcan First Officer, T'Pol. During a long night with Archer and the doctor together in sickbay, Phlox suggests that this conflict may be due to sexual tension:

for the past few months I've noticed increasing friction between you and the sub-commander, you must understand that I am trained to observe these things… when one person believes their sexual attraction toward another is inappropriate, they often exhibit unexpected behaviour (ST: ENT)

During a delicate procedure to transplant a pituitary gland from a Calrissian chameleon into Porthos, Archer asks Phlox whether his expertise on sexual matters was based on professional or personal experience. Phlox explains that he has two wives, who in turn each have two other husbands beside himself. His family unit consists of a total of 720 possible relationships, 42 of which have romantic possibilities, and 31 children (Archer ‘sounds very complicated’, Phlox ‘Very. Why else be polygamous’). The character of Phlox thus represents a complex and fluid chain of equivalences.30 His own sociotechnical background and non-species specific training, his use of alternative and traditional therapies and his non-monogamous group relationship and polyamory all represent floating signifiers which ascribe a diverse fluidity to his subject position. But his status as an ‘alien outsider’, visually marked as different, on board the Enterprise means this estrangement is narratively present, but effectively neutralised.