#the region is called Sápmi and they are Sámi

Text

Etymological origins of the names of the regions of Finland

Suomi, Häme = Of the same origin together with "Sámi". There is no certainty of their etymology, but a common theory suggests they'd be a loan from the Baltic "žemē", meaning "land". However, modern linguists seem to argue that this is also inaccurate.

Satakunta = From Swedish "hundare", a Viking Age and early Middle Age Scandinavian war and governance system.

Pirkanmaa = Possibly from "birk", a special legal protection given to trading centers (early 1200s).

Uusimaa = Translated from Swedish "Nyland" (New Land).

Kymenlaakso = "Valley of Kymi". Kymi is a river. The word itself means... a big river.

Pohjanmaa = "Northland".

Keski-Suomi = "Central Finland".

Savo = From "Savilahti" (Clay Bay), the old name of the Mikkeli area. The origin of "Savilahti" is still debated, if it was originally savi (clay), savu (smoke), sauvo, or possibly a Sámi word for a backwater (savo, savu).

Karjala = A bit unclear. It comes from the word "karja", and if this word is of Germanic origin, then it could mean (war)band.

Kainuu = Unknown. Theories include Germanic loan "kainu/kaino" (lowlands), "kainus" (knob-headed staff, wedge-shaped object), a Sámi origin (compare gaajnuo, gaajnuoladdje (non-Sámi peasant); kai´nōlatj (Swedish coastal peasant); kainolats, kainahaljo (Swedish or Norwegian peasant)), Old Icelandic "kveinir" (an unspecified Northern Nordic people) or Proto-Norse "gainuz" (gap, jaw) -> "kainu(s)" (dragnet, sleigh).

Lappi = The most controversial of them all, I'd say. "Lapp" name usually refers to Sámi people, although they do not like this term so don't call them that. As for the etymological origin of said word, two theories: 1) a translation of an ancient Sámi tribe name "wuowjoš", from the word "wuowˈje" (wedge, patch) -> "lapp" (patch, small piece of paper). Old Finnish term for Sámi people is "vuojolaiset". 2) Meaning a remote area. The region of "Lappi" in Finland is a combination of two lands: Peräpohjola (Back of the Northland) and the areas of Sápmi (in Finnish "Saamenmaa") which are within the borders of Finland. Former land is Finnish, the latter Sámi.

Ahvenanmaa = "Perch land". Two theories: either it comes from Proto-Norse "Ahvaland" (water land?), or the Finnish form is the original.

In Swedish in the cases where it differs from the Finnish origin:

Österbotten = "East Bottom". As opposed to West Bottom, Västerbotten, on the Swedish side of the Baltic Sea.

Kajanaland = From the historical Russian name for Kainuu, "Kajánij/Kayániy". Meaning unknown, though some say it means a land in which it is difficult to travel. Likely, it is connected to the word "Kainuu".

Tavastland = Apparently from Old Norse "Tafæistaland" (ᛏᛆᚠᛋᛏᛆᛚᚭᚿᛏ). Origin unknown, theories say the "ast" part could somehow be connected to Estonia.

Finland = Hahaha. Unknown. Old sources use the word "finn" and variants to refer to both Sámi and Finns and you never really know what's the intention (think of Finland and Finnmark). Theories say that the origin of the word could be connected to Germanic words such as "finthan" (find), "fendo" (wanderer).

Åland = "River land". Two theories: either it comes from Proto-Norse "Ahvaland" (water land?), or the Finnish from "Ahvenanmaa" (perch land) is the original.

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

"While the Venice Biennale has allowed Israel to participate year in and year out, in spite of its designation as an 'apartheid' state by Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and the Israeli human rights organization B’Tselem, Palestine has always been barred from having its own pavilion. To participate in the national section of the Venice Biennale, the country’s independent government must be acknowledged by the Italian Government, disqualifying Palestine.

"The Biennale appears to be politically neutral, following state protocol, but the Venice Biennale is actively involved in making and unmaking countriesʼ statehood. In 2022, the Sámi, a people indigenous to parts of Norway, Finland, Sweden, and Russia, were permitted to use the Nordic Pavilion even though Italy does not recognize the region of Sápmi as a sovereign nation. In March of that same year, the Biennale issued a statement declaring its 'full support to the Ukrainian people and to its artists' and 'expressing its firm condemnation of the unacceptable military aggression by Russia.' Yet, the festival has been deafeningly silent on the atrocities of Gaza."

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sámi Folklore and Magic

The Sámi (sah-me) are the traditionally Sámi-speaking people inhabiting the region of Sápmi, which in modern times encompasses large northern parts of Norway, Sweden, Finland, and of the Kola Peninsula in Russia. This area was formerly known as Lapland, and the Sámi have historically been known in English as Lapps or Laplanders, but these terms are regarded as offensive by the Sámi, who instead claim the area's name in their own languages. The Sámi are primarily known for their relationship with the culture of nomadic reindeer herding. For several complex reasons that I won’t get into here, reindeer herding is legally reserved for only Sámi people in some regions of the Nordic countries.

Learning about my culture has been a very wonderful, eye-opening experience for me and I want to share what I’ve found!

The Sámi, within the circles of people who know them, are recognized for three specific forms of magic. These are divination, drumming, and “gand”. Sámi people and their craft were believed to be very powerful by sagas.

Saivu and Noaidi:

Saivu is a term that typically means “another world”, as well as the being who live there. A noaidi refers to a person with the ability to communicate with spirits, travel to other worlds, and potentially even tell the future. The drum was one of the most critical tools for noaidi carrying out these spiritual tasks.

Faith and Mythos:

There is no set limit to the gods traditionally held in Sámi culture. Norse and Sámi mythology influenced each other frequently, and thus there are many notable similarities between the two. I.e. Both hold a belief in the figure of Thor.

Mythical creatures are a critical part of Sámi culture. Many today still believe in underground spirits, and figures of legend are still described through generations. Stállu (troll giants) and Čáhcerávga (river spirits/sea monsters) are used in stories to scare children from dangerous behavior on the ice or near other dangerous places.

Joik

Joiks are Sámi song traditions used to aid a noaidi in achieving a trance, especially so in pre-Christian dominance. Joiks also have function outside of such spiritual traditions and rituals. They are also used to calm and call to reindeer, and narrative joiks are powerful tools in storytelling.

The Drum

Meavrresgárri - North Sámi

Gievrie - South Sámi

Runebomme - Norwegian (Comes from early misunderstanding that the symbols represented on the drums were runes, newly appearing name is Sametromme)

Many drums are made of a wooden frame (South Sámi) or a hollowed bowl (North Sámi). Each are personalized, with the backs of these drums being decorated with various amulets of silver, animal claws, teeth, or bones. Whenever the drum is hit, the pointers move around and indicate to the symbols on the drumskin. Through this, noaidi are able to tell the future and communicate with gods and spirits. Drums are also powerful tools to aid in putting noaidi into a trance.

Gand

Originally claimed to be a “soul” or spirit that a person practicing Sámi sorcery could control/send out. This could be to gain information about distant lands, or even to cast harm onto others. By those who feared Sámi magic, gand was typically known as a malicious “projectile” of sorts that sorcerers could use at intense speeds and vast distances.

Healing:

Noaidi were believed to be able to heal people by retrieving their souls from the world of the dead. Traditions of noaidi healing are still in use to this day. Stemming bleeding, stopping someone’s bleeding through chanting, rituals and other forms of witchcraft) are still used not only in Sámi tradition but also throughout Norway as well.

Much of Sámi culture isn’t known by those outside of the culture due to much of it being received through oral tradition. It’s very important to respect the closed aspect of the culture, while still learning about important cultural aspects that preserve Sámi people’s place in the world.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Netflixable? Reindeer herders face a "Stolen" way of life in this Swedish thriller

Today’s “Around the World with Netflix” outing takes us to snowy, remote region we outsiders used to call Lapland (Sápmi, is preferred by the locals), that treeline on the edge of the tundra in northern Norway, Sweden, Finland and a bit of Russia. It is the home of the Sámi peoples, traditional reindeer herders who have lived in this cold place for thousands of years.

That makes for a striking…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Note

Hey, I saw your tags on the Arknights post and wanted to say that yes, OP is definitely aware of the name of that region, as it is the land of the Sámi peoples, of which they are one.

They have also made a comment about how that is NOT the name they chose to call their land, but rather a term that is derivative of the slur, that has been imposed on them by the colonisers. The correct term for the region is Sápmi. You can read what OP said about that in the comments on that post!

Aight thx for educating, I just vague remembered a name of a region from my mother tongue and only did a quick check to see if that region has the same name in English sorry

0 notes

Text

Tourists take a reindeer sleigh ride through Levi in Finnish Lapland, the ancestral home to the country’s nearly 10,000 Indigenous Sámi people. Photograph By Parker Photography, Alamy Stock Photo

Stereotypes Have Fueled a Tourism Boom in Europe’s Icy North. Can Things Change?

For decades, tourist experiences such as dog sledding have told a false narrative of Indigenous Sámi traditions.

— By Karen Gardiner | February 3, 2021

Winter visitors arriving in Arctic Europe are presented with a bucket list of activities, from chasing the northern lights to cross-country skiing and, increasingly, racing through the snow on a sled pulled by a team of huskies.

In recent years, dog sledding has become a symbol of Europe’s far north—known as Sápmi to the nearly 100,000 Indigenous Sámi who live there. In fact, a 2018 report by Animal Tourism Finland found 4,000 huskies working in Finnish Lapland alone. The problem? “Dog sledding was borrowed from other cultures and transplanted to Lapland’s tourism scene in the 1980s,” says Tuomas Aslak Juuso, president of Finland’s Sámi Parliament, the representative body for the roughly 10,000 Sámi who live in the country. “It is not a part of Sámi or Finnish culture.”

Besides being culturally inauthentic, dog sledding creates tension with Sámi reindeer herders. Unleashed or escaped dogs risk frightening, mauling, and killing reindeer. “Dog sledding activity is also considered a culturally invasive alien species,” Juuso adds, “causing ecological, financial, health, and social harm to traditional Sámi livelihoods that are originally part of our northern nature.”

This photo, taken around 1890, shows Sámi outside a traditional home. The Sámi are an Indigenous Finno-Ugric people who live in Sápmi, which today encompasses northern Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia’s Kola Peninsula. Photograph By Pump Park Vintage Photography, Alamy Stock Photo

From dog sledding to stereotypical images of Sámi in traditional dress, inaccurate representations of the area’s Indigenous communities have been marketed to visitors for decades. As tourism across Arctic Europe booms—revenue in Swedish Lapland is up 86 percent over the last 10 years—Sámi are finding ways to engage with the industry to tell their stories accurately.

In Finland, the Sámi Parliament in 2018 adopted the Principles for Responsible and Ethically Sustainable Sámi Tourism, a set of guidelines primarily aimed at non-Sámi tourism practitioners working in the Sámi Homeland, as well as visitors.

Highlighting dog sledding (along with the “igloo” hotels that have recently appeared around the region), the guidelines state the potential harm of these “borrowed traditions”—homogenization, “whereby tourist landscapes of the Arctic region begin to resemble one another regardless of [their] diversity and richness.”

Finland’s guidelines are just one step forward in telling the real story of the Sámi people. Across Sápmi, locals are banding together to correct the record, thereby hoping to enrich the travel experience in the region for all.

NGM Maps. Source: Lars-Anders Baer, Sami Parliament, Sweden 🇸🇪

Misinterpreting the Freedom to Roam

The Sámi Homeland in Finland is one part of Sápmi, a large, diverse area that encompasses northern Norway, Sweden, and Russia’s Kola Peninsula. While the northernmost regions of Sweden and Finland are both called Lapland, the entire Sápmi area has been imprecisely referred to as “Lapland” and promoted as an “untouched wilderness,” despite the long presence of people living and working there.

“Even though nature might seem untouched in many places in the North, it is almost always still utilized by the local people,” says Juuso. “The Sámi still use the area for reindeer herding, fishing, hunting, berry picking, and in other traditional ways. This is important to take into consideration when the tourism industry advertises the Finnish customary law of ‘Everyman’s Rights.’”

In the Nordics, “everyman’s rights,” or the “freedom to roam,” is considered a basic human right. In Finland, Sweden, and Norway, anyone can walk, cycle, ski, and camp nearly anywhere. With those rights comes the responsibility to behave respectfully, but visitors often seem less aware of this element.

Outi Kugapi, a tourism researcher from Finland’s University of Lapland, says that poor interpretation of these freedoms has led to tension between locals and dog sledding companies from other countries. “They don’t know anything about the area, they don’t know anyone, so they don’t really communicate with locals,” she says. “[But] they’ve read the everyman rights, that they have the right to be there and do these activities.”

Misunderstanding has led to tourists “wandering around people’s backyards and looking through the windows,” thinking “that this is okay to do,” Kugapi says. Developers make the same mistake but on a bigger scale. Ski resorts built on traditional reindeer grazing lands negatively impact a vital Sámi industry. Meanwhile, Sámi see “the large number of tourists, the litter and how more and more tourists are using the land, but [Sámi people see] very little of the income,” says Lennart Pittja, a longtime tourism professional in Sweden.

Left: Herding reindeer plays an important role in the Sami culture's income and diet. “I fear the government is taking more and more of our land,” says herder Danel Oskal. “I’m afraid that in the future, there will be no more land for the reindeer.”

Right: Aslak Tore Eira is a Sami reindeer herder in Troms County, Norway. Of the estimated 100,000 Sami spread out across northern Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia’s Kola Peninsula, only about 10,000 still herd reindeer for a living. Photograph By Scott Wallace

Though dog sledding is not authentic to the Indigenous Sámi people who live in Finnish Lapland, it’s often marketed to tourists as an Indigenous experience. Photograph By Jonathan Nackstrand, AFP/ Getty Images

Kugapi hopes that the Culturally Sensitive Tourism in the Arctic (ARCTISEN) project she launched with a group of researchers will help. ARCTISEN supports tourist businesses in Finland, Sweden, and Norway in creating products that accurately reflect and benefit the region. Through publications, digital toolkits, and a soon-to-launch free online course, the project highlights negative experiences and encourages local communities to determine how their cultures are used in tourism.

“Entrepreneurs will have concrete tools” for making their businesses more culturally sensitive, says Kugapi. Already, “our activities have raised awareness and made them think [about] tourism differently.”

“Cultural sensitivity is not something you can achieve, it’s more a state of mind, a way of working,” Kugapi continues. “We hope that the material we create will enhance tourism entrepreneurs’ [and] decision makers’ capacities to be more culturally sensitive in the future.”

Decades of Marketing Mistakes

Misunderstanding extends beyond physical spaces to identity. In Finland, which has the largest share of Arctic tourism businesses, marketing missteps about who the Sámi are date back to the mid-20th century, when people started traveling to ski in Finnish Lapland.

Sámi people became “an attraction and started to be used in tourism marketing,” Kugapi says. Tourists’ demand to see traditionally dressed Sámi became so great that workers were told to dress up and pretend they were Sámi. It’s now a single, stereotypical image that tourists have come to expect.

Worse, rituals were invented, such as the “Lapland baptism,” a ceremony in which a “shaman” wearing Sámi dress baptizes tourists. The dubious practice continues today.

Left: A traditional Sámi tent, called a lavvu, sits under dancing northern lights in Abisko, Swedish Lapland. Photograph By Roberto Moiola, Alamy Stock Photo Right: A Sámi reindeer herder tells stories about Sámi life and culture to tourists in Tromsø, Norway. Photograph By Joanna Kalafatis, Alamy Stock Photo

For visitors, seeking Sámi-led and -approved experiences can be complicated. A major problem, says Juuso, is that such experiences are marketed alongside inauthentic products. “Visitors are faced with a serious mismatch of products that may be marketed under the same umbrella of ‘authenticity,’ though only some of the products are truly of local origin,” he says. “And the tourists have no knowledge of how to separate [them].”

The Sámi Parliament in Finland foresees a future Sámi tourism certificate or label with both shared and country-specific criteria, as well as a Sámi Tourism Information Center to offer visitors guidance.

“There is an acute need for creating criteria, rules, and a monitoring system to guarantee the authenticity, responsibility, and ethical sustainability of tourism based on Sámi culture, as defined and accepted by the Sámi community concerned,” says Juuso.

Help For Finding Authentic Products

Such an authenticity program existed in Sweden about 10 years ago. Before it was discontinued due to lack of funding, VisitSápmi awarded the “Sápmi Experience” label to companies offering genuine, ethical, and sustainable Sámi experiences. The sustainable travel organization also tried to promote “more nuanced marketing of what Sápmi is, to get away from this stereotypical way of focusing on clothing,” says Lennart Pittja, who was the program’s project manager.

Throughout the Nordics, other similar efforts are on the rise. The Nature’s Best Sápmi label awards Sámi-led tourism products that meet criteria based on the Swedish Sámi Parliament’s sustainability program, Eallinbiras (“our living environment” in North Sámi). “One of the most important reasons for having a Nature’s Best Sápmi label is to let the Sámi themselves tell their story in their own way,” reads the website’s description.

In Norway, a collaborative project between the Sámi Parliament in that country and Tromsø Municipality launched in 2019 to ensure that information about Sámi culture is respectful. The goal of the project, named Vahca (“fresh snow”), is “for Tromsø to be a pioneer municipality in how to manage Sámi culture in tourism,” according to a statement on the Parliament’s website.

Back in Finland, Visit Finland distributes the country’s Sámi Parliament guidelines in the tourism organization’s “Sustainable Travel Finland” educational workshop, launched last year. “If we are made aware of unethical Sámi tourism practices in Finland … we do contact the company and discuss the principles of ethically responsible Sámi tourism with the company in question,” says Liisa Kokkarinen, manager of Visit Finland’s Sustainable Development project.

Sámi Leading The Way

More importantly, the tourism industries in these countries are seeing the value in having Sámi lead the way. The Johtit Project, whose name translates to “on the move,” is one example. Run by the Northern Norway Tourist Board and supported by the Sámi Parliament in Norway, the project is a network of 21 Sámi-owned tourism businesses offering activities that go beyond the stereotypes.

Left: The reindeer trudge through deep snow to find food in their winter grazing grounds outside Harrå, Sweden. Lichen is the staple of their winter diet, and they must push aside the snow to reach it. The wetter snow associated with warmer temperatures in recent years causes a frozen crust to form over the plants, which the reindeer can't break through.

Right: Frames of lávut are a common sight in Sami yards, where they are used for smoking meat. Sami have long used the tents as portable shelters—their wide bases and forked poles enable them to withstand winds of up to 50 miles an hour on the Arctic tundra. Easy to transport and erect, the frames were originally covered with reindeer skins, but waxed canvas or lightweight woven materials are more common today.

1 note

·

View note

Text

17. Reindeer

“I’ll go see the Lapps. They’re our best chance.”

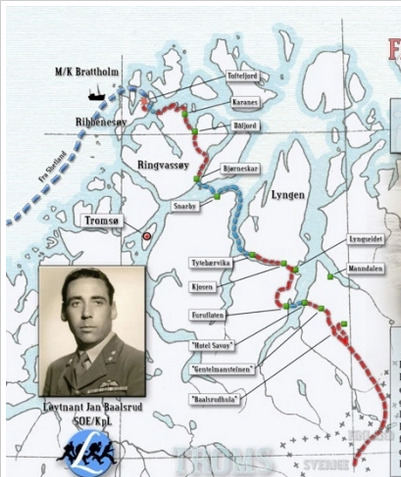

After having it on my list for years, I finally read a David Howarth’s We Die Alone, about a Norwegian commando, Jan Baalsrud, who escaped from the Nazis and by walking, rowing, skiing, and finally by sleigh, made it across the far north Norway, in the Arctic, to finally make it to safety in Sweden. Wikipedia puts it succinctly;

This mission, Operation Martin, was compromised when Baalsrud and his fellow soldiers, seeking a trusted Resistance contact, accidentally made contact with an unaligned civilian shopkeeper, with the same name as their contact, who betrayed them to the Germans.

To set the scene, take a look at this map, from a recent expedition retracing Jan’s exact route:

https://gjeldnes.com/in-the-footstep-of-jan-baalsrud/

Early in his journey, he makes a mistake by trying to charge through a town and outrunning the Germans on skis instead of taking his time and waiting for the all-clear. In doing so, he gets lost in a snowstorm, and nearly dies in an avalanche. He survives, but suffers from frostbite and is unable to walk, making his escape considerably more difficult.

There are many interesting aspects to the story, but I’ll focus on one part I found fascinating: while he was certainly assisted greatly by Norwegian partisans, he never would have made it out without the help of the Sámi people, who, with their sleigh pulled by reindeer, brought Jan to safety.

The Sámi people (also spelled Sami or Saami) are an indigenous Finno-Ugric people inhabiting Sápmi, which today encompasses large northern parts of Norway and Sweden, northern parts of Finland, and the Kola Peninsula within the Murmansk Oblast of Russia.

_ _

The Sámi people of Arctic Europe have lived and worked in an area that stretches over the northern parts of the regions currently known as Norway, Sweden, Finland, and the Russian Kola Peninsula. They have inhabited the northern arctic and sub-arctic regions of Fennoscandia for 3,500 years. Before that they were probably living in the Finno-Ugric homeland.

Source: Wikipedia

In fact, much of the book is about the time he spends waiting for help out in the snow on the side of a mountain, for the Sámi. The Norwegians, afraid of being caught assisting Jan, essentially leave him buried alive in the snow, while arranging for the Sámi to arrive with their herd of reindeer. The plan is for them to take Jan on their way to their summer pastures in Sweden. While the forbidding Arctic winter poses many problems for Jan, including a snowstorm which nearly ends his quest, the snow, providing a winter road for the reindeer, is also his only chance to avoid the Germans and get to Sweden. Sweden, being neutral, would be a safe haven for Jan.

What of the mysterious Sámi, who despite their significance, are relegated to a but a single chapter (17) in the book?

József K.

Perhaps I am interested not only as they are the key helpers in the story but also because my wife’s grandfather, József, a paratrooper in WWII, supposedly made it out of a Siberian prison camp on a sled pulled by reindeer. This is a story passed down by family members and seems almost mythical, especially to someone who grew up in more temperate lands and only knew that reindeer pulled Santa’s sled. And they could fly.

Now, there are other escape stories. Two I am familiar with are Lajos M., a Hungarian who is imprisoned near the Don river. A more popularized story is the “The Long Walk”, about a Polish officer, Slavomir Rawicz, who escapes from a Siberian prison camp in a snowstorm and treks 4000 miles to freedom. Now, this story is controversial, but that is because Rawicz seems to have borrowed the story, so it still likely has some elements of truth, while the names and places might be invented.

And there is more evidence that even if Rawicz didn’t do the walk, someone else did.

We learned of a British intelligence officer who said he had interviewed a group of haggard men in Calcutta in 1942 - a group of men who had escaped from Siberia and then walked all the way to India.

And then from New Zealand came news of a Polish engineer who had apparently acted as an interpreter for this very same interview in Calcutta with the wretched survivors.

These stories are second-hand, and far from conclusive proof, but for Mr Weir, they convinced him that there was an essential truth in the story that he wanted to retain.

“There was enough for me to say that three men had come out of the Himalayas, and that’s how I dedicate my film, to these unknown survivors. And then I proceed with essentially a fictional film.”

_https://www.bbc.com/news/world-11900920 _

Lajos M., 42 éves / Louis M, age 42

This is a book I picked up at my wife’s house, and is a powerful story of a Hungarian, also a paratrooper I think, that is caught behind enemy lines and send to a prison camp. This book solemnly relates Lajos M.’s incredible suffering as he somehow manages to stay alive in a prison camp. Somehow it was published during the communist times, perhaps that’s why it reads a bit darkly, fatalistically (Stoically?) like The Good Soldier Schweik, Catch-22, Chickenhawks, and Slaughterhouse Five, and other war stories of this nature.

He spends 13 years there until they are finally pardoned. I think at one point, like Dostoevsky, he is sentenced to death, but pardoned at the last minute. The story starts out with Lajos, now working at a factory in Hungary, stealing a blanket, so a co-worker wants to find out why one would steal a blanket, and so unravels the long story. You get the gist of the powerful, dreamlike quality of the story in this summary:

M. Lajos magyar közkatona elment a Donig. 1943-ban esett hadifogságba. Fogolyként elment az ember-lakta világ legeslegszéléig. És onnan is továbbment. Tizenhárom év múltán visszafelé is megtette ezt az utat. Hazafelé. Mindig azt tette amit mondtak neki. Csak közben M. Lajos eltévedt a történelemben.

Hungarian Lajos M. went to Don. He was captured in 1943. As a prisoner, he went to the very edge of the human-inhabited world. And from there he went on. Thirteen years later, he made this journey backwards. He always did what he was told. Meanwhile, M. Lajos was lost in history.

Unfortunately Lajos M. is an obscure Hungarian book, and I haven’t been able to figure out if this a true account, or some kind of merging of a bunch of stories, but no question, like Lajos M., József went to the eastern front, and he made it back, somehow.

Now with these precedents, especially with Jan’s story, could this amazing story of a Hungarian rescued by a reindeer be true? Now, it starts to make sense. Why, of course, the only way to escape would be by sled, it is as normal as a car is to us suburbanites, or skis are to Norwegians in the far north.

I have few details of this story other than this grandfather József K. was (as is often the case with paratroopers) captured behind enemy lines. Theorizing here, but the prison camp, being in Siberia, was so remote (perhaps an island as in Lajos M.’s case, or across 7 time zones like Magadan) that it was not as tightly secured as other, more urban camps might be, since it would be suicide to attempt to escape. Alcatraz was not protected by the prison walls, but by the San Francisco bay, with cold waters, strong currents and sharks.

In a recent New York Times article on Magadan, the caption to one of the photos echoed this idea

Clearing snow by a lighthouse. Residents refer to the rest of Russia as “the mainland,” a sign of how isolated the city feels.

The story goes that somehow József was assisted by some locals, and placed on a reindeer sled. No one “drove” the sled, according to my wife, “the reindeer knew the way to the next town.” And this is how Grandfather returned home. Now, why would these locals help a prisoner, a foreign invader? Given that they were herdsman, perhaps they realized József was a long-lost cousin, from their nomadic past? This is me entirely theorizing here, but there are tribes in Siberia that live a semi-nomadic existence, almost like American Indians in the States used to, and their language is (distantly) related to Hungarian.

The core Khanty vocabulary still contains numerous examples of vocabulary inherited from the Finno-Ugric proto-language (Collinder, 1962). Khanty is predominantly an agglutinative language with no prepositions and numerous affixes, each of which expresses a particular function.

Jan

Now, getting back to Jan’s epic tale.

With Jan’s tale, exhaustively corroborated in We Die Alone, as Howarth retraced Jan’s steps to validate the story, and even talked with the villagers who helped him, surely there is truth to József’s story too.

This certainly leads to the question of how much help the Norwegians were in the first place. For starters, the ethereal patriotism of the Norwegians is the main reason why the commandos were exposed. The commandos had a list of helpful partisans, so when they landed in Norway they made the unfortunate mistake of talking to the owner of a grocery store whose name matched one of the partisans on their list. However, in a twist of fate, it turned out he was not the person they were thinking of, he just happened to have the same name and now owned the same grocery store after the owner died. Surely some of the fault goes to the commandos, who aren’t careful enough to vet the supposed partisan, and they further compound the error the mistake by being nice and letting this chap go, and depend on his honor not to turn them in.

The grocer wrestles with the matter a bit before making a compromise and calling the town mayor or some other official to inform him, instead of calling the Nazi party directly.

Here’s a movie based on Howarth’s book:

Howarth notes the theory that the locals take their time in alerting the authorities, on the notion that this will give the commandos a chance to escape. Sadly, this nice gesture was not communicated to the commandos, but even if it had, they had no chance of escape in their sluggish fishing boat.

The Pathfinder?

This gets to an interesting side question on the subject of whistle blowers, much in the news these days, and I propose two simple types:

(1) the whistle blower who squawks because they fear for their safety if they don’t squawk and get caught

(2) The whistle blower who, at the risk of his own safety, blow the whistle because of a greater calling.

The Norwegian grocer and others who compromise the mission are “whistle blowers” in the former sense, allying themselves with the foreign Nazi menace due to fear of persecution. Here’s the reasoning of the Norwegian official who turns the commandos in:

“The story was bound to spread, and the Germans were bound to hear it; and then the official himself would be the first to suffer.”

Howarth does not discuss what happens to the few commandos who survive, but we can infer their suffering was great.

Now, as is the case with many pondering this story from the comfort of their armchair like myself, it is easy to blame the weak-willed grocer and local officials for talking, but we were not there, and likely, when push comes to shove, I would do the same I suppose.

Who knows what makes people like Oskar Schindler, a onetime wealthy businessman and Nazi sympathizer, to later put their life on the line? Christopher McDougall explored this idea in “Natural Born Heroes”, when he described a diminutive woman who disrupted the attack of a school shooter, despite, until then, having done nothing out of the ordinary. For another excellent study of this idea, see The Pathfinder, a film by Nils Gaup, in which a young man has to decide whether to save himself, or help a tribe chased by Russian invaders.

Most of the Norwegians Jan meets as he attempts to escape, while they are trustworthy and helpful, are very careful in extending any assistance. For example, rather than hiding Jan in their homes, the partisans keep Jan lodged first in an abandoned, unheated hut, and then nestled in a snowbank at the top of a valley.

To me, this alone is one of the most astounding challenges Jan faced. Clearly, the Norwegians were assuming the Sámi would arrive “any day now”, but as they are to find out, the Sámi have a different timetable. Howarth, like the frustrated Norwegians, seems to take issue with the Sámi and their concept of “the vague imponderable future”

Heroes

Howarth’s book focuses on the many Norwegian’s who assist Jan, so don’t need to mention them here as their story can be found in better detail in the book. There is the midwife who helps him recuperate after his initial escape, and the old Norwegian, Lockertsen, who puts himself greatly at risk, because he rows Jan across the fjord, going at night to evade any Germans potentially on watch, and drops Jan off at Ullsfjord.

The Sámi

No question the locals put their lives at risk, in fact over 100 Norwegians assisted Jan, but my thesis is that the Sámi are the great heroes of this story, next to Jan Baalsrud. Yet the Sámi are not even mentioned in the summary on the book’s back cover, and only are fully covered in the last chapter.

Howarth seems to take a dim view of the Sámi, considering them opportunists simply out for the trinkets that the Norwegians give them as payment. Further, he notes their strange concept of time “the imponderable future”, and other puzzling differences. Now, anyone who knows a strange culture, say the Hungarians, well, aren’t these admirable characteristics instead? As shown below, the Sámi herdsman who ultimately takes Jan to safety ponders the task, as he stands still for 3-4 hours, watching Jan.

Had Jan taken a similar amount of time to plan his route, rather than barreling through the middle of the town, depending on the prowress of the Norwegians in skiing, and the Germans lack of ability in the same, he might not have gotten himself in such a predicament.

I can’t imagine how he finally made up his mind to take him, but certainly the difficult state that Jan was in, and that he would surely die if he stayed in Norway, perhaps swayed him.

[Scene: Jan is in his snowbank refuge. After waiting there, above the village for almost a month, he has given up all hope. It took every ounce of strength of a few villagers to get him to a plateau where they hoped the Sámi would be. For the villagers, the Sámi with their reindeer would be like a helicopter to one of us, stuck on a mountain. But the snow is melting…]

When he opened his eyes there was a man standing looking at him. Jan had never seen a Lapp before.. the man stood there on skis, silent and perfectly motionless, leaning on his ski-sticks [ski poles, my British friend]. He had a lean swarthy face and narrow eyes with a slant. He was wearing long tunic of dark blue embroidered with red and yellow, and leather leggins, and embroidered boots with hairy reindeer skin and turned-up pointed toes.

In fact, this was one of the Lapps whom the ski-runner from Kaafjord had gone to see on his journey a month before. He had just arrived with his herds and his tents and family in the mountains at the head of Kaafjord, and must have been thinking over the message all the time. When he had first been asked, the whole matter was in a vague imponderable future….He did stand looking at Jan for three or four hours.

Howarth goes on to mention the blankets coffee brandy and tobacco procured at “enormous prices” to give to as payment for the escape. Other Sámi had turned down the offer, so we can gather they understood the risk, and knew the trinkets would not pay for a loss of life, but luckily for Jan, this Sámi (we never learn his name) agrees.

The next thing that brought Jan to his sense was a sound of snorting and shuffling, unlike anything he had ever heard before, hoarse shouts, the clanging of bells and a peculiar acrid animal smell, and when he opened his eyes the barren snow-field around him which hadd been empty for weeks was teeming with hundreds upon hundreds of reindeer milling around him with an unending horde, and he was lying flat on the ground among all their trampling feet. Then two Lapps were standing over him talking their strange incomprehensible tongue….They muffled him up to his eyes in blankets and skins, and lashed him and everything down … There was a jerk, and the sledge began to move.

A lapp on skis was leading it. It was one of the bell deer of the heard, and as it snorted and pawed the snow and the sledge got under way and the bell on its neck began a rhythmic clang, the herd fell behind it, five hundred strong.. the mass of deer flowed on behind, it streamed out in the hurrying narrow column when the sledge flew fast on the level snow.

All day the enormous beasts swept on across the snow.. the most strange and majestic escort ever offered to a fujitive of war.

Hurrah! How exhilarating! I picture the start of the American Birkebeiner ski race, with thousands of skiers churning up the snow, or the giant Vasaloppet in Sweden with 20,000 skiers.

I imagine that was a swell ride too, for József K, to finally leave the prison camp for home.

The Man Who Never Gave Up

https://nordnorge.com/en/artikkel/jan-balsrud-is-the-man-that-never-gave-up/

As Far as My Feet Will Carry Me

Here a German escapes from a Soviet prison camp in Kamchatka and eventually finds his way to Iran. As with “The Long Walk”, there are doubts as to the authenticity of the story.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zaq88ixc-FY

The Pathfinder

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pathfinder_(1987_film)

How The Long Walk became The Way Back

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-11900920

** **

Lajos M., 42 éves

https://www.antikvarium.hu/konyv/csalog-zsolt-m-lajos-42-eves-lajos-m-aged-42-37420

**The Good Soldier Švejk **

_The unfinished novel breaks off abruptly before Švejk has a chance to be involved in any combat or enter the trenches, though it appears Hašek may have conceived that the characters would have continued the war in a POW camp, much as he himself had done. _

The book includes numerous anecdotes told by Švejk (often either to deflect the attentions of an authority figure, or to insult them in a concealed manner) which are not directly related to the plot. [Source: wikipedia]

The 585 people appearing in The Good Soldier Schweik: http://honsi.org/svejk/?page=4&lang=en

Magadan, Russia

Nine Lives / Ni liv (1957)

youtube

1 note

·

View note

Audio

FREE DL : Mari Boine - Vuoi Vuoi Mu (Pérola Branca Edit) by Cosmovision Records

C๏sʍ๏tune ★ 2 - @perolabranca Mari Boine - Vuoi Vuoi Mu (Pérola Branca Edit) Release date: May 21 | 2019 Label: @cosmovisionrecords Mastering by: @felipenadeau ⋘ ────── ∗ ⋅◈⋅ ∗ ────── ⋙ We are really happy to welcome our second guest Pérola Branca for our playlist : " Cosmotunes". They made a beautiful edit of "Vuoi Vuoi Mu " by the norwegian Sami artist Mari Boine. ⋘ ────── ∗ ⋅◈⋅ ∗ ────── ⋙ About @perolabranca : "Pérola Branca is the project formed by the producers @gutopedigone and @mandruvamusic , longtime friends and creators of several underground parties in Minas Gerais, Brasil. The name means "White Pearl" in portuguese, which came out, actually, from an LSD trip when they both could see a shiny weird pattern though a piece of glass but spent 2 hours trying to describe the details. After this peculiar process and agreeing they were both seeing an white perl, they realised that they were seeing the same thing but in a completely different way. The Pérola Branca is, after all, the concept of how people see the world through their own lenses, experience it in their own way and, still, are able to have empathy with untranslatable and unique feelings." Follow their vision @perolabranca ⋘ ────── ∗ ⋅◈⋅ ∗ ────── ⋙ About Mari Boine (https://ift.tt/1aDkmlk) She was born and raised in Gámehisnjárga, a village on the river Anarjohka in Karasjok municipality in Finnmark, in the far north of Norway. Boine's parents were Sami. The Sami people, also spelled Sámi or Saami, are the Arctic indigenous people inhabiting Sápmi, which today encompasses parts of far northern Sweden, Norway, Finland, the Kola Peninsula of Russia, and the border area between south and middle Sweden and Norway. Their traditional languages are the Sami languages and are classified as a branch of the Uralic language. They made a living from salmon fishing and farming. She grew up steeped in the region's natural environment, but also amidst the strict Laestadian Christian movement with discrimination against her people: for example, singing in the traditional Sami joik style was considered "the devil's work". Sami languages, and Sami song-chants, called yoiks, were illegal in Norway from 1773 until 1958…in Russia, Sami children were taken away when aged 1–2 and returned when aged 15–17 with no knowledge of their language and traditional communities. As Boine grew up, she started to rebel against the prejudiced attitude of being an inferior "Lappish" woman in Norwegian society. Boine's songs are strongly rooted in her experience of being in a despised minority. She allways give a positive message thru her music, often singing of the beauty and wildness of Sapmi (Lapland). The title track of 'Gula Gula' asks the listener to remember 'that the earth is our mother. On 7 October 2012, Boine was appointed as a "statsstipendiat", an artist with national funding, the highest honour that can be bestowed upon any artist in Norway. ⋘ ────── ∗ ⋅◈⋅ ∗ ────── ⋙ Vuoi Vuoi Mu Lyrics Versions : #1#2 Vuoi my little yellowbird Vuoi my summernight bird cuckoo and eagle Vuoi my swallow Vuoi my swallow with nest under riverbanks Vuoi night owl with limitless vision Vuoi vuoi me Vuoi vuoi me Vuoi vuoi joy Vuoi vuoi joy with hearty laughter Vuoi sorrow Vuoi sorrow with oceans of salty tears Vuoi vuoi frost Vuoi vuoi frost winter and cold Vuoi summer with burning hot days Vuoi vuoi me Vuoi vuoi me Download for free on The Artist Union

0 notes

Text

Liberating Sápmi with Maxida Märak and Gabriel Khun

This week we are pleased to present an interview William conducted with Gabriel Khun and Maxida Märak on the 2019 PM Press release Liberating Sápmi: Indigenous Resistance in Europe’s Far North. This book, of which Khun is the author and editor and Märak is an contributor, details a political history of the Sámi people whose traditional lands extend along the north most regions of so called Sweden, Norway, Finland, and parts of Russia, as well as interviews conducted with over a dozen Sámi artists and activists.

Maxida Märak is a Sámi activist, actor, and hip hop artist who has done extensive work for Indigenous people’s justice. All of the music in this episode is by Märak and used with her permission, one of which comes off of her 2019 full length release Utopi.

In this episode we speak about the particular struggles of Sámi folks, ties between Indigenous people all around the world, and many more topics!

Links for further solidarity and support from our guests:

Pile o´Sápmi: http://www.pileosapmi.com/ WeWhoSupportJovssetAnte: https://wewhosupportjovssetante.org/ Gállok Iron Mine: http://www.whatlocalpeople.se/about/ Ellos Deatnu!: https://ellosdeatnu.wordpress.com/ Moratorium Office: https://moratoriadoaimmahat.org Arctic Railway: https://www.ejatlas.org/conflict/the-arctic-railway-project-through-sami-territory-from-finland-to-norway

. ... . ..

Music for this episode in order of appearance:

Maxida Märak - Järnrör

Maxida Märak - Kommer aldrig lämna dig - Utopi - 2019

Maxida Märak cov. Buffy Sainte-Marie - Soldier Blue

Check out this episode!

0 notes

Video

youtube

Áillohaččat (Ingor Ántte Áilu Gaup & Áillohaš)

Sápmi, Vuoi Sápmi! (Sápmi Lottážan I),

Audio recording, 22′ 26”, 1982

The yoik, a Sámi musical form that differs from what is commonly known in Euro-American music, was banned as devil’s music under centuries of Nordic suppression of Sámi culture, particularly by religious fundamentalists who went as far as associating it with drunkenness, sin, and barbaric behaviour. Áillohaš re-kindled the yoik as a living cultural form, introducing the unprecedented use of instruments. Joikuja (1968) was the first step in making this Sámi practice widely available. In the inaugural meeting of the World Council of Indigenous Peoples of 1975 in Port Alberni, Turtle Island (Canada), Áillohaš’s yoik is said to have electrified the delegates present, connecting deeply with their Indigeneity. This secured the acceptance of Sámi peoples within the larger international community, at a time when legal debates for Indigenous rights across the globe were gaining significant credence. Alf Isak Keskitalo, Pekka Lukkari, Ole Henrik Magga (who went on to become the first president of the Norwegian Sámi Parliament), Esko Palonoja, Aslak Nils Sara, Per Mikal Utsi, and Ingwar Åhren accompanied him as representatives from Sápmi.

Sami artists played an important role in one of the biggest public actions linked to environmental issues and exploitation in modern times. The People’s Action against the Áltá-Guovdageaidnu Waterway (c. 1978–1982) radically shook the course of history in the Nordic region. Its call to “let the river live” was launched against the construction of a large dam across the legendary Álttáeatnu River in Sápmi / Northern Norway. It grew from an unexpectedly broad movement across civil society, including Sámi, Norwegian, and international solidarity. The Áltá action grew in reaction to the profound impact that the flooding of large areas of Sápmi would have on Sámi communities, their livelihoods, cultural heritage, as well as on their role as environmental protectors.

As part of the social justice movement that developed across the Nordic region demanding Sámi rights at the time of the Áltá action, Áillohaš put together a series of recordings emblematic of the times. Sápmi, O Sápmi! is a recording with a circular sound geometry. Field recordings of the peaceful region, the river around which the controversy revolved, and the violence of the action, the ominous buzzing of police helicopters and the sound of protesters, were interlaced with the yoiking of the young Sámi musician Ingor Ántte Áilu Gaup. In this sound work, the yoik takes on a leading role as a mediator between the cosmos, nature, and humanity, and as the guarantor of a meaningful connection between all things.

0 notes