#the necrophilic landscape

Photo

new site

new books

new newsletter (drawing by angela fanche)

+ a 30-70% OFF sale. last 2 days...

stephen can you re-tumbl?

#2dcloud#big ticket#compact magazine#the necrophilic landscape#parc#frozengirl#stephen z hayes#morgan vogel#jul gordon#iku kawaguchi#raighne#yvan algabé#sarah cuje#brian bamps#liza kotlar#ellen plant#ash hg#samuel r delany#blaise larmee#katherine dee#altcomics#clair gunther#angela fanche#maggie umber#caveh zahedi#lale westvind#tara booth#paul peng#josiah parker#jason overby

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

#van gogh#necrophilic landscape#morgen vogel#sorrowing old man#at eternity's gate#comics#altcomics#alt comics

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

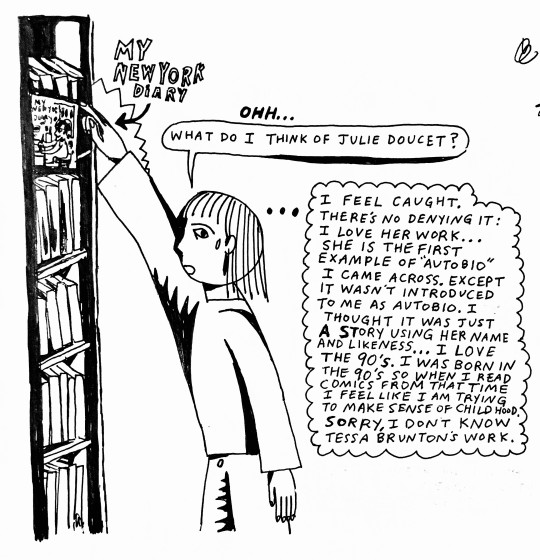

The Necrophilic Landscape by Morgan Vogel reviewed by Jason Overby

(2023)

Available for purchase at 2dcloud

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Necrology" is a literary work that delves into the realms of death, decay, and the blurred boundaries between the living and the dead. In this interview, authors Gary J. Shipley, Kenji Siratori, and Reza Negarestani provide insights into the themes and approaches within the book. The discussions touch upon topics such as horror, writing practices, and the merging of corporeal entities. Through their unique perspectives, the authors offer a glimpse into the dark and unsettling landscapes explored in "Necrology." Exploring Horror and Decay: The authors acknowledge that death and decay permeate every page of "Necrology." Gary J. Shipley considers reality itself as a horror, describing it as a carnivorous fog that devours people. Kenji Siratori presents a vivid imagery of the hells within bodies, evoking a sense of horror through surreal and visceral descriptions. Reza Negarestani notes that horror stories inherently concern decay, even when they delve into other themes. Together, these perspectives create a tapestry of unsettling and morbid explorations. Writing Practices and Approaches: Each author provides insights into their writing practices. Gary J. Shipley describes eavesdropping on the polluted organs of imagined creatures, engaging in graphomania fueled by nihilistic incoherence. Kenji Siratori's writing is characterized by a distinctive and chaotic style, drawing inspiration from the mysteries of the mind and the grotesque. Reza Negarestani mentions the necessity of making a pact with putrefaction and exploring the moment of nucleation with nigredo, emphasizing the intertwining of decay and creative expression. The Layout and Subject Matter: The two-column layout in "Necrology" is seen as a means to blend and unite the main bodies of text, reinforcing the themes explored within the book. Gary J. Shipley envisions mechanized deformities and blended tissue, while Kenji Siratori describes the brain of the dead in surreal and enigmatic terms. Reza Negarestani highlights the intimate relationship between intelligibility and a necrophilic intimacy, suggesting that the layout mirrors the fusion of living and dead elements. The Black Slime and the Destiny of Texts: The authors speculate on the destiny of the texts in "Necrology." Gary J. Shipley envisions cloistered hollows, vampire dreams, and inevitable absorption. Kenji Siratori describes the image of a centipede's lung and the apocalypse of the sun. Reza Negarestani discusses the necroses of the soul, emphasizing their role in the arrangement and intelligibility of the universe. Together, these visions evoke a sense of transformation and decay, emphasizing the interplay between life and death. In "Necrology," the authors engage with themes of death, decay, and the merging of living and dead entities. Their discussions highlight the horror inherent in existence, the unique writing practices employed, and the connections between layout and subject matter. Through their distinct perspectives, Gary J. Shipley, Kenji Siratori, and Reza Negarestani offer readers a glimpse into the unsettling and thought-provoking world of "Necrology."

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

When I Was A Princess

Ever since I was a little boy, the role of royalty in fairy tales has always confused me. My grasping young mind seized upon princesses ... their beautiful costumes, their perfect hair, how they always seemed to get the happy ending they wished for (whether or not they really deserved it). But my mental picture of life as a medieval princess had been mostly formed by Disney movies and treacly storybooks, and these cotton-candy fantasies were, of course, way out of whack with the harsh actualities of the Middle Ages: stinking gutters, festering sores, tooth decay, mass starvation. In fact, being a real princess probably sucked, day-to-day, though I'm sure it was still substantially nicer to be a princess than a peasant. I'd reckon that it still is.

I’ve come to realize that my fascination with princesses was due more to the aesthetic and romantic awakening such tales ushered into my imagination than any real admiration for wealth. Growing up as a queer kid, in every sense of the word, and trying to figure out my place on the gender spectrum, I had to admit that I often identified more with princesses than princes. Princesses had better outfits, for starters, and simpler narrative arcs; they basically had to just wait around for a handsome prince to come along, and he would whisk them away to an enchanting castle, which presumably had good ventilation and abundant fireplaces, and life would forever after be perfect.

The messages us kids got from these stories were of dubious morality. Cinderella married out of her class by virtue of her comeliness, an impractical shoe, and a little magical trickery. Sleeping Beauty was a princess disguised as a peasant, who could only be rescued from her coma by a wealthy and apparently none-too-picky heir. Snow White married a would-be necrophile. Rapunzel was a captive virgin with good shampoo.

An observant friend of mine once said about Disney movies that it was “better to not look under the hood.” These are the shitty takeaways I got from watching Disney tales: “Girlfriend Be Trippin’ If She Thinks She Can Marry Into Wealth And Escape From Her Lowly Social Strata ... But Oh Wait, Here Comes Drunk Magic Grandma, Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo, Have A Hoopskirt And Some Pearls, There, Problem Solved”; “Girlfriend Better Not Turn Sixteen Because She Already Pissed Off The Green Sorceress Just By Being Born An Attractive Female And Now She’s Gotta Watch Out For Dragons And Country Antiques, Oops, Well, Shit, She Pricked Her Finger And Now She's In A Coma, What A Bummer, Hope A Horny Prince Shows Up”; “Girlfriend Better Not Eat That Drugged Apple After Getting High As Balls On Mushrooms And Singing To Wildlife And Shacking Up With Seven Random Dudes She Met In The Woods Because Sleep-Rape Is Apparently An Acceptable Practice In This Moral Landscape, And By The Way, Her Stepmother Is A Murderous Witch Who Asked A Hunter To Bring Her Bloody Heart Back In A Box”; “Girlfriend Better Stop Singing About Freedom And Mobility And Start Reinforcing The Patriarchal Order Through A Sad Regime Of Self-Denial Or Else She’ll Be Cursed By The Scary Octopus Drag Queen Into Having A Body That Probably Menstruates”; “Girlfriend Better Not Try To Educate Herself Through Reading But Should Instead Cave In To Stockholm Syndrome So She Can Come To Love Her Hairy And Violent Captor Who's Really Deep Down A Sensitive Guy, Honestly, Despite His Animal Rages And Dangerous Possessive Behaviors And Obvious Psychological Instability”; “Girlfriend Better Cooperate With Racist Colonialists If She Knows What’s Good For Her”; “Girlfriend Better Dress Like A Dude And Wield A Sword To Get Anywhere In Life”; and so on.

Why did the storytellers of yore aggrandize the aristocracy? Weren't kings and princes and dukes, at least historically speaking, usually the oppressors? When many of these popular fables were being formed, the peasants were still suffering under the rule of the fortunate few. The real history of royalty is rife with incest, inbreeding, religious persecution, torture, suppression of dissent, excessive taxation. So why, then, were the rich and powerful so often made into the centers of our fairy tales? Why do we cheer for the “charming” prince, who rides into the scene and sweeps our poor lady protagonist up and away to a better life? Why do we lionize the merciful king who throws lavish balls and stays executions, or thrill to the plots of the wicked queen? Why do we confuse true love with economic agency?

We do this because power makes for a seductive escape. It's easier to imagine being rescued. The prince just showed up, with white teeth and a white carriage ... what could possibly go wrong?

But when I went to college and studied history and actually got a chance to view images of real royalty in action, I had to admit my disappointment. What I saw looked nothing like what Disney and company had prepared me for. All those tapestries and etchings revealed a much sadder, grimier life.

Poor princess. I see her in her lonely tower, wearing a dumb conical hennin and a heavy-lidded, somewhat dopey expression. She has the double chin, pouty mouth, and baggy eyes of a medieval woodcut, and she always looks like she’s suffering from a bad cold. She's attended by maids and a homely matron and maybe a unicorn, and she’s pretty much resigned to a lifetime of making bad embroidery and mooning over dreamy brigands. Her “entertainment” mostly consists of watching sad syphilitic jesters or doing that lame limpwristed dancing courtiers used to do. You know the kind I mean ... twirling about and hopping with hands upheld, bowing to one another, prancing back and forth across the flagstones, making uneventful circles, all to a namby-pamby melody of sackbuts and flutes. Blech. Given that I'm a homosexual with a crinoline in his closet, you'd probably think that I'd be gleefully clapping my hands for all this cutesy curtseying and jangling of tambourines and such ... but insipid pageantry totally turns me off.

It's really no different today. We have become so removed from the primary objectives of survival that we seek to derive meaning from media depictions, from virtual representations, rather than through our own direct experiences. We talk about movies now rather than myths, celebrities instead of heroes, plots instead of legends. We are encouraged to define ourselves by the roles we occupy within businesses, by our placements within economic taxonomies, and not by our vocations or passions. We accept the narrative that hard work and fair play will get us to a place of stability and harmony, to a land of plenty, and are disappointed when we don't get the expected results. The American Dream itself is a form of fairy tale, one in which each of us will get the castle we so richly deserve. For some, the handsome prince is a one-way ticket past the moat.

Reality television is so popular because it perfectly reflects the boredom and spiritual vacuity of our culture. We get off on rehab redemptions, ugly duckling makeovers, riches-to-rags stories. We obsess over famous trainwrecks, simultaneously envying and scolding those who are richer and more reckless than we'll ever get to be. In watching their lives unfold before us, we want to feel an attendant rush of adrenaline, while avoiding actual discomfort or injury. We ridicule celebrities for their failings, while aping their influence and purchasing the products they endorse. We gravitate towards images of the rich and powerful, yet we relish every reminder of their human frailty. Our grocery store aisles are filled with shame and schadenfreude. The next time you’re at the market, just take a look at the tabloids glaring at you. Look at all those princes and princesses, publicly flayed for real or imagined sins.

We used to slay dragons; now we covet expensive sneakers. We used to tell tall tales of royalty; now we tell tall tales of supermodels and gangsters. Not much has changed ... just the bling.

I remember learning as a kid how important brands had become. One's identity was tied to adherence to a brand strategy. Of course, being a nervous adolescent, I got just as caught up in the horseshit as everybody else. In middle school, I once threw a hissy fit because a pair of cool girls two grades above me suggested I wear a particular sweater/collared shirt combo, and my parents simply couldn’t afford it. I stamped my feet and howled and wished that I could be more like the princesses, who dressed smartly and had lots of money and who seemed to wield some kind of power that the rest of us didn’t have.

Since then, though, I've learned a thing or two about class. I discovered, with a mixture of surprise and relief, that it's been the same since the days of Versailles: your class and your economic prospects can often be determined by the costumes you wear. Sometimes a person's character is not described so much by their own interests, their strengths, their morality, but by their adherence to (or outright rejection of) a quickly changing code of fashion.

That said, people who actively transform themselves to better reflect their inner lives really move me. I am stirred by self-actualization, especially in the face of stifling conformity. One day in downtown Seattle, I saw a transwoman in what was obviously an early stage of public interfacing, walking out of a building for what may have been the very first time. And I say this without a drop of condescension or snark, but rather with the deepest admiration ... I was impressed. I could see her nervousness, the shaky breath she took before stepping out of the vestibule. I could tell that this was a giant leap of faith she was taking. It would have been wildly inappropriate for me to approach her, but I so desperately wanted to. I felt such a strong urge to cheer her on that tears came to my eyes; instead, I just gave her the biggest smile I could, which was returned with some visible relief. So I’ll say now what I wanted to say to her then.

“I see you, sister, taking your first tentative steps out in public. I see that you are making an artwork of yourself, revealing the sculpture of your femininity with a chisel. Okay, maybe at this point it's more like you’re using a jackhammer, but still … you’re working to define yourself aesthetically and conceptually. You're becoming who you were always meant to be. Maybe you’re just beginning this transformative work, armed with only with a tube of shitty dimestore lipstick, an ill-fitting dress, some awkward heels, a crooked wig … but the results, for all their sincerity and pluck, are beautiful. You are so much more a real princess in my eyes than Cinderella or Sleeping Beauty or any of those other doe-eyed confections Disney sold us on. I see your courage and your commitment. I see your grace revealing itself in stages. I see your majesty, your majesty. You don’t need a prince to rescue you. You’re rescuing yourself. You go, girl.”

When I was a kid, I wanted to be a princess, sort of … though I secretly and more fervently envied the starchy villainesses, with their high eyebrows and pointy shoulders and severe hair. They had more glamor, and power, and there was something satisfying about their unremitting bitchiness, something that spoke to my own nascent and unsatisfied cruelty. But I grew out of it. So now this is what I want to say to the younger me, the one who wanted to be a princess, or a queen: forget about the damnable royals. There's no time to waste in aping them bitches. Become yourself. Your youth is going to pass so swiftly. Focus on your family, your best friends. Ignore the cool kids, the shiny popular ones with good hair and good clothes, because they will peak early, and unremarkably. It'll be the outcasts who matter to you in the long run. Stick with the lonely ones, the nerds and the misfits and the dark mysterious ones with hooded eyes, because you will spend decades adoring them, because they'll become your most loyal friends, the ones who will see you and accept you for who you really are. Focus on your real wealth: the people you love, the people who will love you back. The fake princesses will die a thousand daily deaths, suffocated by their peroxide and pearls, humiliated by their own vanities … while you will remain surrounded by jewels, your genuine ones, your flawed and pitted and perfect treasures, your heroes, your royalty.

0 notes

Text

The Modus Operandi for Ritual Abuse–Torture

Changing the Landscape: Ending Violence—Achieving Equality, a study conducted by the Canadian Panel on Violence against Women (1993), is a credible report funded by the national government that names ‘‘ritual abuse’’ as a definite phenomenon of violence, identified as occurring in every region of Canada (p. 45). Pat Freeman Marshall, co-chair of the panel, stated that it heard stories of violence that she could relate only to the torture endured within prisoner-of-war camps (Cox 1992). ‘‘Tortured’’ was the word frequently used by women who spoke to the panel of their childhood ritual abuse victimization. Victimized persons repeatedly reported that they were tortured, so the term ‘‘ritual abuse’’ does not fit for them. Nor does that term comprehend the brutality, degradation, and dehumanization that one bears witness to when listening to the universal and transnational childhood stories of women, youth, and men involving both abuse and torture. Thus, the term ritual abuse–torture (RAT) was coined. A child, whether born into or taken into such families or groups, will endure the following violent ordeals in ways that reflect the idiosyncrasies of the perpetrators:

Child abuse. Going without food, being forced to sleep on the floor without bedding, and being called ‘‘good for nothing’’ may accompany pedophilic assaults that occur night or day. In these families or groups there is no safe place for children—they may be finger-raped in the car on the way to school or raped in bed or on a cold, hard barn floor.

Terrorization. Threatening, intimidating, and forcing the child to witness the harming of animals or other children delivers the message: ‘‘Don’t tell. If you do, this will happen to you.’’ If only one parent is involved in the ritual abuse–torture, he may threaten to kill the nonoffending parent.

Human/animal brutality. Using violence against a pet instills terror, promotes silence, and helps establish totalitarian control over the child. One woman, for example, described being forced to watch her father burn her pet rabbits alive. Such cruelty prevents the child from forming attachments to pets or to anything as they are made to feel that they are to blame for the harm animals suffer. Perpetrators know that nonattachment keeps the child feeling isolated, abandoned, and alone in his/ her victimization. Another act of cruelty commonly forced onto animals and children is bestiality.

Physical, sexualized, and mind–spirit tortures. There are no limitations to creative brutality. Tools useful for torturing, many commonly found in ordinary households, include belts, wooden bats, and wire clothes hangers useful for whipping and beating. Rope is used for tying children down, hanging them by their limbs, or looping around their necks. Knives, razor blades, and forks are cutting and scraping tools; hot spoons, hot stove elements, and lit cigarettes burn; toilet bowls, bath tubs, and sinks are used for holding the child’s head and face under water; cattle prods are for electric shocking; and pepper blown into the child’s eyes causes excruciating pain. Dog cages become child cages, a dog’s dish and food become the child’s dish and food, and a dog collar and leash control the child who is commanded to eat and be the dog she is told she is. Soiled cat litter, all forms of human bodily fluids— blood, urine, vomitus, semen, menstrual fluid, feces—are serviceable for smearing. Physical and sexualized pain, dehumanization, and degradation inflict fatal wounds upon the child’s relationship with herself, overwhelming her ability to cope, forcing her to have out-of-body experiences or to disconnect and dissociate. Feeling like an ‘‘it’’ and objectified further by enforced overdrugging, trained to self-harm, and schooled to be the ‘‘perfect victim,’’ the child faces a reality so severely altered and distorted that she becomes a danger to herself—at risk for suicide. All these torturous actions are directed by the ritual abuse–torture parent, family, or group in an attempt to destroy the humanness of the child victim. Such intentionally destructive actions are acts of human evil (Staub 1993).

Pedophilia. Rampageous hard-core parental pedophilic violence can and does occur at any time. Weekends, holidays, and school breaks are ideal times for a child to ‘‘disappear’’; absences are explained as visits to relatives or trips to summer camp. When the victim is the perpetrator’s child, pedophilic victimization is convenient, happening right in the home, in commercial buildings owned by the perpetrator, in summer or winter cottages, campers, hotels, motels, on boats, farms, or simply outdoors.

Necrophilia and necrophilic-like acts. The child victim may be overdrugged, hooded, choked, beaten, near-drowned, or suffocated into unconsciousness. Such experiences are often expressed by the child as ‘‘the darkness came.’’ This satisfies the ritual abuse-torturer’s need to express domination over life and death. Raping the child’s ‘‘dead-like’’ body gratifies the fiend’s hunger for sado-necrophilism.

Horrification. Beyond a state of terror, horrification involves seeing, hearing, smelling, feeling, and experiencing heinous ordeals perpetrated without moral restraint. Horrification leaves the child speechless, voiceless, without verbal language, for there are no words that can describe horror. Shocked, shivering from the depth of inner coldness, the child’s body tremors in response to being family- and gang-raped and forced into pornographic bestiality with large animals, such as horses, which are known to be used in bestiality (Associated Press 2005; Chronicle- Herald 2004; LifeSiteNews 2005).

Organized violent family and group gatherings. These gatherings are commonly coded as ‘‘rituals and ceremonies.’’ Ritual abuse-torturers intentionally use rituals to orchestrate pedophilic torture, which is the defining characteristic and central purpose for family and group gatherings.

Suicide and other self-harming acts. Some children are forcibly taught, conditioned, or programmed to self-harm and self-cut as a way of ‘‘forgetting,’’ replacing ‘‘remembering’’ with pain—then pain and forgetting with relief. Depending on the practices of the ritual abuse–torture family or group, the degree of self-harm conditioning and programming can include forcing the child to practice ways of committing suicide. This tactic provides protection for the perpetrators. If they fear a child is telling, they can attempt to force the child into committing suicide to prevent being exposed.

Exploitation and trafficking. Within ritual abuse–torture families and groups, a child can be exploited and trafficked locally, nationally, or transnationally, ‘‘off-street’’ or ‘‘on-street.’’ Off-street exploitation—transportation and trafficking—happens when the child is taken to family and group gatherings to be victimized. Trafficking off-street also happens when outsiders—pedophiles who are not members of the ritual abuse-torture family or group—‘‘rent’’ the child. When the child’s body has developed, becoming unmarketable to pedophiles, the child might be forced by ritual abuse-torturers to work on-street. ‘‘In-house’’ or ‘‘on-site’’ trafficking happens when ritual abuse-torturers organize ‘‘a party’’ in their home, for example. Often forced into criminal activities such as drug trafficking, the child is also used in all forms of pornography.

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

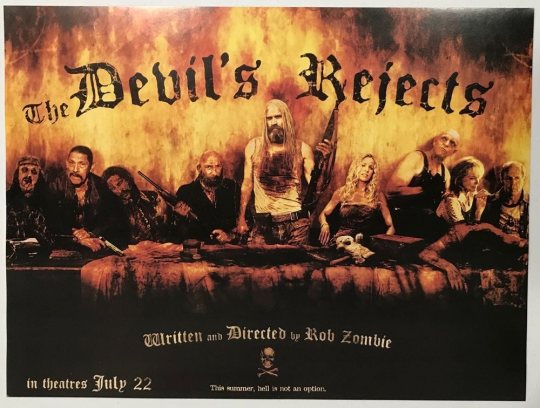

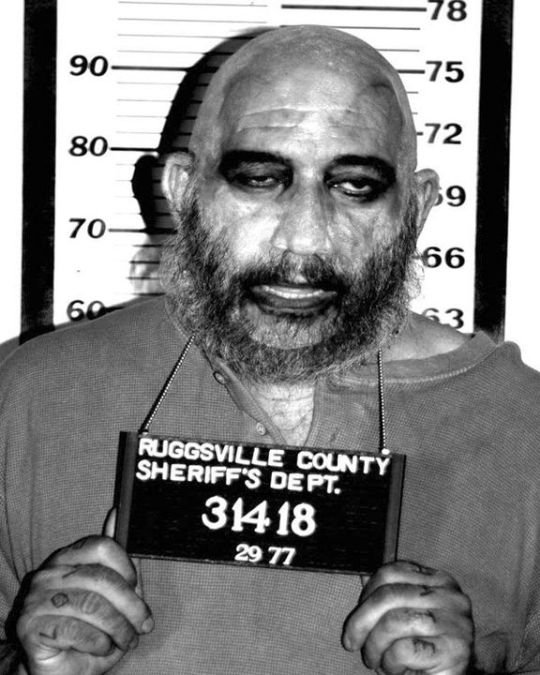

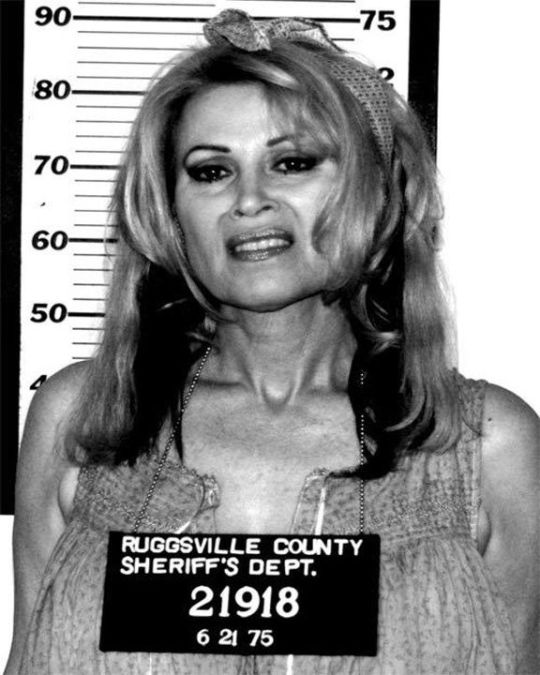

BLOGTOBER 10/2/2018: THE DEVIL’S REJECTS

The core ethos of Rob Zombie’s movies, if you can say that there is one, is individuality: a certain don’t-give-a-fuckness, a matter of being yourself at all costs, even if that means cutting holes in your pants for your ass to hang out of, not brushing your teeth, and murdering people who piss you off. In the spirit of that level of realness, I must confess that, even though I don’t have a lot of desire to defend it, a part of me really wants to like this messy, self-satisfied movie. Unfortunately, I can’t come clean about why, but that’s because I don’t really know.

It’s worth mentioning that THE DEVIL’S REJECTS is Rob Zombie’s sequel to his first feature, the incomprehensible HOUSE OF 1,000 CORPSES. This is worth mentioning precisely because it’s worth forgetting. The latter disaster, which to be fair Zombie was forced to make up on the spot in an impromptu pitch meeting, and which was plagued with production problems, amounts to a loose collection of pornographically violent cartoons, motivated by nothing other than the director’s love for his own ideas. It isn’t easy to take, but at least they are his own ideas. Whether or not I find it entertaining, I can find my way to appreciating a filmmaker just mashing up his personal fetishes, when so many movies are boringly predicated on one person’s condescending projection of what all of OUR fetishes are. Ultimately, Ho1KC’s lack of structure and...maybe I wanna say, point...makes all this fantasizing pretty irrelevant to anyone other than the fantasizer. Mercifully, THE DEVIL’S REJECTS finds Zombie squeezing a more carefully curated selection of his obsessions into a plot, with some character arcs and everything.

Ok, so it’s not like a masterpiece of mythology or anything. In fact, the movie’s fatal flaw, in spite of all this new coherence, is that it’s still too hard to tell what the point is. THE DEVIL’S REJECTS rescues the three strongest characters from its predecessor--Otis and Baby of the savage Firefly Clan, and Captain Spaulding, an ambiguous character from the first movie who is outed here as Baby’s father--and makes them over for this new effort. Their transition from being so broad that they might as well be puppets in a children's show, into salt of the earth psychos who you can practically smell, is a natural consequence of the new environment in which DEVIL’S REJECTS finds them. In fact, this sequel is part of a totally different genre than the Ho1KC, which clumsily smooshes together THE TEXAS CHAIN SAW MASSACRE and SPIDER BABY and THE ROCKY HORROR PICTURE SHOW. The new movie, however blood-drenched, sets out for something more like Sam Peckinpah territory. There’s a brief moment I like at the beginning of the movie, when Spaulding--or Cutter, as he’s more casually called here--peels out to go rescue Baby and Otis from the bloody police raid on the Firefly compound. You see the dusty, dilapidated shack where Cutter lives, fenced off from an apocalyptic-looking wasteland, and then as he swings out into the road, the rich green expanse of an industrial farm. The new world of the Fireflies is utterly mundane, even depressed, a place whose banality is shattered only by the random acts of violence perpetrated by our defacto heroes.

It’s a big relief to not to have a bunch of shrill, spoiled teenagers squirming around, existing only as living opportunities for cartoon villains to demo their personalities. DEVIL’S REJECTS rejects this obligatory horror trope, in an important first step toward Rob Zombie finding his footing as a filmmaker. He not only positions the ostensible bad guys more clearly as heroes, which falls in line with his true feelings, but he populates his movies with grownups. This sounds simple, but in an entertainment landscape dominated by co-eds finding themselves, and 30-somethings acting to the best of their ability like co-eds finding themselves, it’s extremely inviting to see adults in all shapes and sizes with creased faces, aging flesh, and wiry muscles clinging to the bone against the ravages of gravity. Groovy young nubiles are seen only in battered photographs, usually beaten beyond recognition.

Therein lies the rub, though--in the movie’s ambiguous victimology. We know that the media-dubbed Devil’s Rejects are responsible for the torture, rape, murder, and necrophilic violation of a growing mass of apparent innocents in Ruggsville County. In the context of the movie, they do away with a handful of touring country signers, in order to force them to help unearth Otis’ buried arsenal, and to hide out in the group’s hotel room until Cutter catches up with them. Of course there’s plenty of sadistic thrills in the mix, but the question remains: What do the Devil’s Rejects usually do? What I mean is: The Sawyer clan only busts out the chainsaws for trespassers. Jason Voorhees kills violators of a set of stuffy social mores. Freddy Krueger kills primarily for revenge. In HOUSE OF 1,000 CORPSES, the Firefly family seems to kill mainly to punish smug, judgmental tourists. But it’s hard to figure out what the Rejects really want in the present film, and this is pretty hard to ignore when they’re construed as outlaw folk heroes. With all their ferocious family loyalty, swagger and charisma (and what Rob Zombie takes to be sparkling banter, but is mainly just the word “fuck” repeatedly so often that it achieves a zen-like obliteration of meaning), it’s clear that we’re supposed to like these guys. But, if they just kill people for no reason most of the time, and I don’t even see enough of it to get a sense of how everything shook out, then I have to start thinking that maybe they’re just a bunch of assholes. Certainly when they’re degrading and torturing their victims to death at great length in a seedy hotel, the droning HENRY: PORTRAIT OF A SERIAL KILLER-type music communicates to me that I’m supposed to think of this murder as a bad thing, a depressingly unnecessary tragedy perpetrated by...you know, a bunch of assholes. And you don’t go on to play “Freebird” over a majestic slow motion shootout for a bunch of assholes. Do you?

Obviously Rob Zombie is doing something right, because I’ve seen this movie several times before, and I have now written an amount of analysis of it that no normal person would ever want to read. But here I am, grappling with my feelings about the movie’s atmosphere, its look, its genre-bending story. Probably the safest thing for me to say now, in the continued spirit of the movie’s fierce individuality, is that I am actively looking forward to the next movie in the series, THREE FROM HELL. I’m ready to be disappointed, but I’m also ready for Zombie to continue to flesh out what it really means to be a Firefly. Fingers crossed that there turns out to be more of the latter than the former.

#blogtober#rob zombie#sherri moon zombie#sid haig#bill moseley#the devil's rejects#house of 1000 corpses#thriller#action#slasher#road movie#western#sheri moon zombie

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

W11, W12, W13

30/12/2020

Waking the dead, life, love and gossip

Flakey, flake, flake flake. I admit it, I let myself down and my nearest and dearest. Oh, the fucking self pity. Despite the ever changing rules and regulations over lockdown, we had planned to get out and walk with our respective menfolk during Christmas and New Year. We set a date and located a route. The forecast looked splendid—crisp and clear—it was going to be amazing. The day came round. I got up late, too late for my early morning climbing session with my daughter. I got dressed in my walking gear, and half an hour before leaving I couldn’t do it. I just could not walk out the door. So I cancelled and went back to bed. Yup, the diary of a depressive. Jen was her usual sage self and pointed out it was ‘twixmas’ and everyone was feeling shit, upside down and the wrong way round, and I should stop beating myself up about it. As Jen and A were already on route they continued on and later sent a breathtaking photograph of the high moor with the sun setting in one direction and the moon rising in the other. Studying the image on my phone in bed, I might have been peering into another world—a martian landscape, the light from the setting sun scattering a Persimmon glow across the moor grass—bronze and gold, molten lava, heat and searing passion. Dear Persephone, Queen of the underworld, you should eat all the seeds. These are winters treasures. Am I looking at a take from an African plain or perhaps a still from the film Dune? No, this is Dartmoor in searing clarity. The sky divided, storm grey cloud drawn low on the horizon and above an endless cyan—a blue to swim in. I could breath the freshness, feel the cold stinging my skin. Oh, the guilt and longing. So, I went out for a run to try and temper the physical yearning, and the next day messaged Jen to see if she could squeeze in another Dartmoor visit, with the promise that I wouldn’t bail this time. Two seconds later—a ping back with ‘Hell yes’.

This time we kept our sights local, and though not a long walk we were going to colour in three whole squares on the 365 map: W11, W12 and W13. It felt like an accomplishment, nearly a full house—a line of colour beginning to emerge on the southernmost part of the map. The proposed route bypassed our previous walk to Western Beacon and headed for Ugborough Tor. The day arrived and clearly Santa Claus had been kind to Jennie. She cut quite a dash in her new walking gear, all booted and suited with military style walking shoes and thermal clothing. We exchanged gifts. From me to her a pair of essential gaiters—or ‘garters’ as Jennie likes to call them, and from her to me, some stylish ultra retro sunglasses. We agreed walking on the moor does not mean having to leave aside fashion. We parked up in the tiny hamlet of Harford and headed straight for St Petroc’s church, a Grade 1 listed building dated to the late 15th / early 16th century.

On this grey mizzly day at the very end of the year, the church looked bleak and unwelcoming. It wasn’t helped by the metal grill shuttered across the porch with a blunt no entry notice. We mooched around the graveyard at the rear of the church. Neglected and overgrown, it had a definite gothic air. We read the gravestones and pondered over the groupings of names and families. New to the term, I find out we are quickly becoming ‘tapophile’s’ or ‘grave stone tourists’—a person whose hobby or pastime is visiting cemeteries, graves and epitaphs; not to be confused with ‘necrophile’ and the perversion of showing a sexual or physical interest in the dead! Not so much a morbid past-time, but one that is curious about past lives. Anyway we are apparently in good company as Shakespeare was supposed to have been a ‘tapophile’, and the related study of ‘taphonomy’ investigating processes of decay in archeology sounds fascinating and important. The hierarchal order of a graveyard is telling. Usually the bigger the slab the more powerful, influential and wealthy the incumbent, closely followed by the decorated memorials of war heroes protecting the former, whilst the women and children and those that had to live out the consequences of the deeds of the big slabs are marked by simple headstones. With this in mind when we came across a large plot encircled by low iron railings, containing a headstone marked John Jeffrey Dixon, 1756-1828, and surrounded by several smaller plaques, engraved with initials and the year of death all listed as 1855, we were intrigued. What could have happened? Were these children? A family tragedy, disease or perhaps a virus or infection?

I should not be surprised to discover that I have leaning towards taphophilia. Death came a blunder-bussing down my family’s own door a few autumns ago bringing with it a tsunami of destruction that took away three loved ones in a matter of weeks. In our highly polished antiseptic 21st century lives, tragedy is supposed to happen elsewhere, on the telly or as macabre titillation on news feeds. Having seen the havoc caused by the sweep of death at such close quarters, I seem to have developed an ear for the hidden tragedy that lies behind the bureaucratic recording of birth and death dates. One such story came with the accommodation that Al rented in the early days of our relationship. He lived in what was part of a 15th century manor house, in the quarter that would have housed cattle whilst the servants lived above. It was basic and cold—think rickety immersion heaters, cranky plumbing and layering up to go to bed—it was also delightfully romantic and we found our own ways to keep warm. Sometime in the mid 19th century the resident family, farm-workers, lost all 9 children in a matter of months to either cholera or diphtheria, the parents surviving probably because they drank mead and not the contaminated water. Some of our friends said they picked up prickly vibes in one room, but we never did, though there was the one time when I woke up in the night to someone blowing gently on my leg dangling out of bed. It was so focused, like someone blowing through a pea-shooter on skin, and then it was gone. It definitely wasn’t Alex, he was snoring contentedly next to me, nor were there any drafts in that particular area, and so overcome was I by my primordial nighttime terror that I dare not look under the bed. I could never find a rational explanation for it, other than a waking dream, perhaps? I like to think that if there is any paranormal phenomena out there, spirits or otherwise, they would be up for having a laugh and hiding under the bed playing ghoulish peek-a-boo. Never mind wailing ghosts and ghouls, the universe seems set up for tragedy and comedy, see-sawing together, tempered with a dose of absurdity to keep the balance.

But how to imagine the desperation and hopelessness of loosing all your children, of not being able to do anything—no mercy forthcoming, from god or layman, through prayer or witchery. Heart wrenching, gut wrenching, unrelenting grief. The stuff of nightmares and surreal in the telling. A tragedy, they say. Indeed, a tragedy that reveals the limits of knowledge, failing systems and medical bungles. Death can tell so much about a time, and I needed to find out what had happened to this family in 1855.

I found limited information online so I contacted the church secretary and swiftly received a response that explained that a memorial existed inside the church to the Dixon family. The Dixon’s had been a local family, the father John Jeffrey Dixon dying in 1828 leaving behind a family of six daughters and one son. The daughters never married or had children and continued to live with their mother Mary Romeril Dixon. The son married and moved away. The eldest daughter Sophie Dixon (1799-1855) was a poet, of the Romantic tradition, and had had some of her work published. Maintaining a household of seven women and living the life of a published female poet in the early 19th century suggests a level of education, cultural knowledge and financial comfortability, however I could find no further detail on the fathers preoccupation. Instead I was delighted to find copies of Castalian Hours. Poems by Sophie Dixon (1829) online, alongside two travelogues she had written about walking on Dartmoor: A Journal of Ten Days Excursion on the Western and Northern Borders of Dartmoor (1830) and A Journal of Eighteen Days Excursion on the eastern and Southern Borders of Dartmoor (1830).

I find an online copy of the two journals bound together with an unauthored handwritten note that describes how the ‘two journals are seldom found together, and in this state are exceedingly rare’. The unauthored note instructs the reader not ‘to despise the untutored writing’ instead recognise that Dixon recorded what she actually saw, and ‘that she really saw a great deal more than most people’. Written nearly 200 years ago, the journals read anything but ‘untutored’ instead they present a style ahead of their time, combining acute observation with opinion that covers a range of subjects from education, poverty and religion that would not be out of place amongst the current plethora of travelogues and writings about place today. Nor was Dixon a faint heart—she was an endurance walker, with Donna Landry writing in The Invention of the Countryside how Dixon was not averse to enduring ‘incredible discomfort and fatigue’ walking up to 28 or 30 miles a day, and that she wrote to ‘expend feeling as much to capture or contain it’ (2001: 239). This is an impulse I can relate too. She was 30 years old when these works were published and was writing at a time that saw the countryside shift from being seen, at least by the middle classes, as a dangerous and impoverished place, to becoming appreciated for its leisure and therapeutic value. Despite Sophie’s passion for Dartmoor and poetry, little is recorded of her life unlike her male contempories—the walking poets—Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworth, nor are her writings given due acknowledgment in the round up of important historic literature about Dartmoor. A woman writing about walking across Dartmoor—a harsh and unforgiving landscape at the best of times—and being published at a time when women weren’t allowed to go to university is no mean feat. Sophie’s poetry and writing reveal a sensitivity, of trying to capture the immensity and rich diversity of the moor; an artist, creating through doing, striding out in all weathers, feeling the raw elements, being buffeted by the wind on the high tor’s. And all in Georgian attire, heavy skirted, possibly with pantaloons and with no GORE-TEX or triple layered waterproof performance technology in sight. Despite her absence in the text books Landry observes that ‘the slightness of Dixon’s oeuvre is no measure of the significance of her achievement’ (239). My impression after reading her works, is a writer who is capable, forward thinking, engaged in current affairs and confident in communicating her thoughts, yet I have so many remaining questions about Sophie that perhaps a historian will give the time to uncover. She deserves to be more than just an initial or a footnote in history.

But what of her death and her family? In her preface to Castalian Hours Sophie writes about the loss of her father and subsequent grief and illness effecting her writing, however further tragedy was to come. According to the GRO death certificate her mother died of heart disease on the 14th December, 1855 aged 80. Three days later her younger sister, Emma Romeril, died of Peritonitis, and ten days after that, on 27th December, Sophie herself died from what is recorded as Typhus at the age of 56. The two other sisters, Cora and Lucy, who are listed on the church memorial and on the grave stones as dying in 1855, actually died two weeks apart in 1876 at the age of 69 and 70 respectively of Bronchitis and exhaustion, a contagious illness undoubtedly spread through close contact. How they all came to be listed as dying in 1855 is a mystery, with the assumption given that the memorial was erected when the brother Clemsen Romeril died in 1893, and that somehow the dates were conflated or misremembered.

***

Wide, open moorland, away from the clutter and noise of modern life where we are constantly ‘ON’, hyper-stimulated, reading the codes, the signs, the subtext. Classification and analysis, polish the mask and smile ‘ta da', who do you want me to be today? It is exhausting. From my studio, I used to watch my chickens scratching and busying—pre bird flu lockdown—and envied their freedom, whilst I was penned in, tied to a screen and working 10/12 hours a day. Sometimes I forgot to move, going hours without drinking or eating. I had become a battery hen and no matter how many golden eggs I laid it was never enough. Putting in numbers and words that churned out more numbers and words until one day the machine broke. Now I have become frozen, a glitch in the matrix, stuttering and locked in. I have to rebuild, start again, set a new framework but to do that I have to first find a way to reboot the frozen system.

We marched up the hill chattering eagerly, airing and giggling over the silliness of families and Christmas frivolities. Despite the chill in the air we warmed up quickly and had to stop to strip off layers, breathing heavily and taking in the sweeping view. It stopped us in our tracks, the vastness of the rolling landscape calming us down, bringing us back to rights. Body and earth, right here, right now. We were heading for Spurrell’s Cross, a medieval stone cross that marks the crossing of two old tracks, one running from Plympton Priory to Buckfast Abbey and the other from Wrangaton to Erme Pound, but we had been too cocksure on setting off, wrongly assuming we were on familiar ground. As a result of our cocksurety we had missed the path and, as is becoming routine on our walks, we once again found ourselves stomping over tussocky ground. The lesson learnt from this walk is that perspective changes everything—so obvious in hindsight but familiarity, as they say, breeds contempt, which in our case was for the map. We were walking on the east side of Western Beacon and though only a few miles into our walk we had quickly become disorientated. The ground undulated unexpectedly hiding the tors previously used as landmarks and we realised that we hadn’t quite got to grips with distance on the map, and as a result could not work out whether we were too far north or south? Scanning across the moor, and with better long distance eyesight than I, Jen spotted a shape partially camouflaged against the moor grassland. With nothing to lose, except our bearings, we ploughed ahead and thankfully hit base, laying hands on the cold stone of the old cross in gratitude. Back on track, we were able to stroll comfortably up to Ugborough Tor.

A space to decant—we talk about all sorts, everything and nothing, from work to children, to ageing and sex; to clothes, cooking, cars, consciousness and ex's—the ex's are most fascinating, the other women, they are set up as the opposition that we share so much in common with and who you can never, ever, know too much—to fungi, lovers, philosophy and death. It is not so much Sex and the City but Sex and the Moor. Everything gets emptied out and overturned. Nothing is trivialised, it all has its place—the worries, the niggling anxieties, superstitions; the casting thoughts that might dissolve into nothing or rankle away and fester without the ear of a trusted confident. Our grandmothers were right all along, a good airing, whether clothes, houses, babies, people or thoughts, makes everything feel better. Men and children so often fascinated by what women talk about… and no wonder, women talk about the under belly of life, paring back the fat and gristle, sifting the wheat from chaff. The talk that unites, strengthens social bonds and builds trust—what social psychologists refer to as cultural learning. In the stone age, this chatter was crucial for sharing information that would enhance survival, and whilst we no longer have wild animals to fear, sense checking about who’s who and what’s what remains essential for our well being.

As children, Jen and I used to be fascinated by our mothers afternoon chats, tongues loosened by a dab or two of sherry. We’d quietly linger in the kitchen, turning the tap ever so softly to get a glass of water, or sit on the stairs ostensibly playing, all the while zoning in on the hushed tones, regularly punctuated by raucous laughter, our eyes widening at what we heard. Rogue men and wildish women, the drawn out agony of someones death, money—the lack there-of; clothes and weight gain, diets, boobs, hot flushes and farting. When they caught us listening they’d call us elephant ears and the conversation would drift to more mundane matters. On occasion the conversation would lower to a whisper, to more darker talk. We’d strain hard, catching snippets of a violent man and a vulnerable child. The school bully, the blond and pretty girl, always with shiny new things turned out had a not so happy home. This was a grown-up world that was somewhere else, far more entertaining and scandalous than watching an illicit late night episode of Dallas or Dynasty huddled together under the bed clothes.

Today out on the moor we find ourselves talking, amongst other things, about the origins of cellular life—as you do. Where once life was understood to have started at a particular point in time and from there on in evolution began spiralling outwards in a chronological timeline from A to Z. We’ve all seen the poster, some of us have the T-shirt—cell blob, lizard, monkey, ape-man, human, Trump. Then some clever spark asked the question, if life started at A—assuming it was down to 'abiogenesis'—where life emerges from non-living matter through natural processes as opposed to counter theories that posit life came from outer space, then surely life must have emerged previously, and continues to appear at point B and C, and so on and so on? Between huffing and puffing up the hill, it is not so much the biology but the shift in the question that fascinates us—alter the boundaries and framework of the question and a whole different perspective opens up, revealing the wood and not just the trees; the whole picture and not just the jigsaw piece. No surprise that Jen and I have dabbled in statistics—she in teaching the subject and I by presenting different sets of data, coloured pie-charts illustrating how the Arts can change lives, which is very difficult to prove in evidential terms but ask a slightly different question and the coloured pie-charts will look ever so pretty, so give us some money, please. It is all about the questions, the scientists and statisticians cry. If only we could step outside of ourselves we might understand so much more. But it is hard to shake off our human skins.

Keep turning the stone over and take a walk around the hill. Anything and nothing. Our conversation continues to spiral upwards and outwards. We bat around ideas, snippets of information snatched from radio, social media, books, conversation—finding relevancy, knitting them together. It feels like moulding and sculpting, work in the studio with most falling to the floor as detritus. The artist Paul Klee said drawing was like ‘taking a line for a walk’, and so it is with conversation—take it for a walk and give it a good airing. Walking in the time of viral contamination is vital. It has become the new 18th century coffee-house, the place renowned for scintillating conversation (if you were a man of course); it is George Seurat’s glistening Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, minus the fancy pants and with walking boots, purpose and pace. It is the city flaneur but without the pomp or privilege. It is Piet Mondrian's Broadway Boogie Woogie, but without the boulevards and pulsating lights. It is our mother’s sherry and Sophie’s journals. Hitch up your skirts and put on your garters and take a walk on the Wild Side. A walk in the park. An escape. Let the words wander or wonder, drawing shapes, hitting dead-ends and taking u-turns.

From the origins of life, depression and death our drawing circles around to the language of love, with Jen telling me how the ancient Greeks had several words for different kinds of love: love for children, love for god, sexual love, self love, whereas in the English language ‘love’ is pinned to its romantic roots—the all or nothing kind, of passion and intensity, valentines cards, red roses and the impossible happy ever after. We find ourselves wondering what is the word to describe the love between old friends?

We reach Ugborough Tor, the temperature has dropped and we think it might snow. In truth, this is the southernmost tor as Western Beacon is not classified as a tor. There are four rocky outcrops: Creber’s Rock, Eastern Beacon, Beacon Rock and Ugborough Beacon; several cairns and a tumulus—an ancient earth burial mound. The view to the East is striking, what is known as Beacon plain slopes gently away then suddenly descends steeply into a valley, so abrupt is the descent that we can’t see the bottom from our vantage point on the tor. The effect is dizzying; the fields and houses rising upwards on the yonder side of the valley look like play mobile houses. We are 378 metres high (1240 feet) above sea level and can see the A38, or the Devon Expressway, snaking northwards. Jennie points out a prominent landscape feature, what looks like a Drumlin, a large teardrop shaped hill probably caused by the receding ice flow of the last ice age some 11,700 years ago. It was previously understood that Dartmoor lay beyond the ‘Quaternary glaciations’ however recent research of the landscape has challenged this notion. We amble our way back and it starts to snow; big heavy flakes, some the size of coins come down thick and fast. We are alone in this vast landscape and run and whoop like children. Back at our cars, as we turn to say good bye, we shout ‘I love you’ to each other. I think we might have always said this, but now we know somewhere it has a name.

Later, I look up Aristotle’s definitions of ‘love’, in particular ‘philia’ which is usually translated as friendship love, or ‘brotherly love’, denoting an altruistic loyalty between equals. This research takes me on a journey that considers what Aristotle defined as ‘good’, and ‘diakaios’, meaning what is ‘fair’, ‘just’ and ‘right’ in accordance to the laws of the universe—laws that draw on the ancient Greek idea that there exists within the universe an order. According to Simon May in ‘Love: A History’, Aristotle elevates ‘philia’ above all other forms, including romantic love and the virtuous love of god. May then goes on to explain how self-knowledge, a virtue much prized by the Greeks, is essential to becoming a well-balanced human being, yet Aristotle understood that ‘it is hard to know ourselves’, we are masters of our own deceit and that we need the aid of a ‘second self’, a person who holds similar values but serves as a mirror reflecting back to us who we are. May goes on to explain that it is not so much that our second self tells us who we are, but that we see in them a part of ourselves, quoting Aristotle directly ‘… with us [humans] welfare involves a something beyond us, but the deity is his own well-being.’ Of course, for this to work the second person has to be the right person—a person who has similar virtues, or values, as ourselves, then ‘philia’ becomes ‘diakaios’—‘when it is in accordance with the laws of the other person’ nature … If love isn’t in such accordance it is inauthentic and hollow’. (67)

How does this analysis of love, nearly 2400 years old, relate to my life long friendship with Jennie? Without a doubt Jennie is suitably different in character to myself—more gregarious and outgoing, her humour is deliciously wry and observant; she is clever, astute and canny, her readings of people and situations are always spot on and she is open-minded whilst still being firmly rooted in reality (the latter being a virtue that I cannot always say about myself); she is a fierce and protective mother, committed to family; ambitious and tenacious. Equally, she is interested in ‘self-knowledge’, if not ‘self-love’, which our deferent Englishness finds a little too gushing, however, she has never been afraid to look in the mirror and face her demons, to own up, reflect and rebuild. Her honesty about our lived contradictions—how we say one thing and do another, that we self sabotage to avoid shattering our fragile self-image and so on—is so refreshing in a time when you might be socially hung drawn and quartered for taking thoughts and words for a walk that do not directly fit the current view. Some of these characteristics I share, others extend my world view. If she serves as a second self, then hell, I need to learn to love thyself! I can count on three fingers the friends I share this type of relationship with, though I’d argue that we are constantly shaping ourselves against our interactions with others—whether children, parents, the shop-assistant, the teacher or colleague. Perhaps I need to be more discerning in my choice of lovers and husbands, as when it comes to the language of love I am clearly better at ‘philia’ than the ‘eros’ kind. In the meantime I’m going for a walk.

SC

Reading

Crossing, William. (1888) Amid Devonia’s Alps; or, Wanderings & Adventures on Dartmoor Plymouth: Simpkin, Marshall & Co. Online, 05, January, 2021: https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/Amid_Devonia_s_Alps/lfoVAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1

Dixon, Sophie. (1829) Castalian Hours. Poems. London: Longman, Orme, Hurst, Brown, and Green, Print.

Dixon, Sophie. (1830) A Journal of Eighteen Days Excursion and Dixon, S.(1830) A Journal of Ten Days Excursion on the Western and Northern Borders of Dartmoor. Online, 05, January, 2021:https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=d_4GAAAAQAAJ&hl=en_GB&pg=GBS.PA2

Evans, D.J.A. and Harrison, S. and Vieli, A. and Anderson, E. (2012) 'The glaciation of Dartmoor : the southernmost independent Pleistocene icecap in the British Isles.', Quaternary Science Reviews., 45 . pp. 31-53.

Landry, Donna. (2001) The Invention of the Countryside: Hunting, Walking and ecology in English Literature, 1671-1831. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

May, Simon. (2011) Love: A History. London: Yale University Press.

Sampson, J. ‘Women Writing on the Devon Land: The Lost Story of Devon Women Authors up to circa 1965’. August 13, 2018. Online, 05, January 2021: https://newdevonbookfindsaway.blogspot.com/2018/08/on-ways-to-old-literary-roads-around.html

0 notes

Text

There are many dead in the brutish desert,

who lie uneasy

among the scrub in this landscape of half-wit

stunted ill-will. For the dead land is insatiate

and necrophilous. The sand is blowing about still.

Many who for various reasons, or because

of mere unanswerable compulsion, came here

and fought among the clutching gravestones,

shivered and sweated,

cried out, suffered thirst, were stoically silent, cursed

the spittering machine-guns, were homesick for Europe

and fast embedded in quicksand of Africa

agonized and died.

And sleep now. Sleep here the sleep of dust.

There were our own, there were the others.

Their deaths were like their lives, human and animal.

There were no gods and precious few heroes.

What they regretted when they died had nothing to do with

race and leader, realm indivisible,

laboured Augustan speeches or vague imperial heritage.

(They saw through that guff before the axe fell.)

Their longing turned to

the lost world glimpsed in the memory of letters:

an evening at the pictures in the friendly dark,

two knowing conspirators smiling and whispering secrets;

or else

a family gathering in the homely kitchen

with Mum so proud of her boys in uniform:

their thoughts trembled

between moments of estrangement, and ecstatic moments

of reconciliation: and their desire

crucified itself against the unutterable shadow of someone

whose photo was in their wallets.

Their death made his incision.

There were our own, there were the others.

Therefore, minding the great word of Glencoe’s

son, that we should not disfigure ourselves

with villany of hatred; and seeing that all

have gone down like curs into anonymous silence,

I will bear witness for I knew the others.

Seeing that littoral and interior are alike indifferent

and the birds are drawn again to our welcoming north

why should I not sing them, the dead, the innocent?

Hamish Henderson, 1942, from End of a Campaign

9 notes

·

View notes

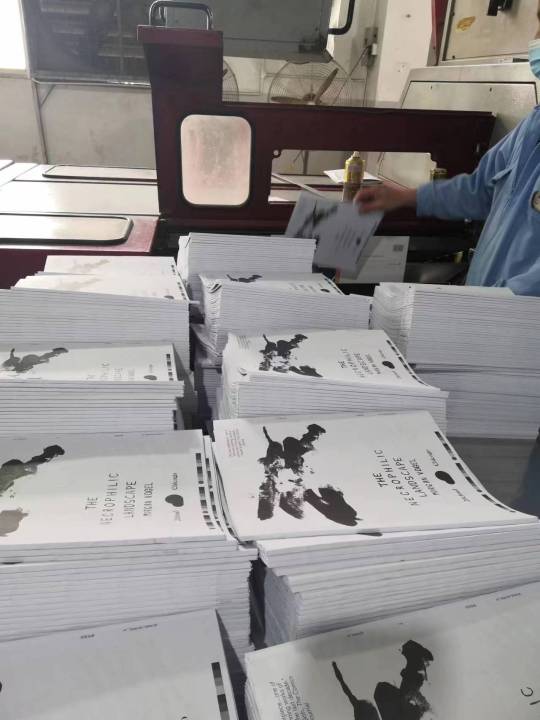

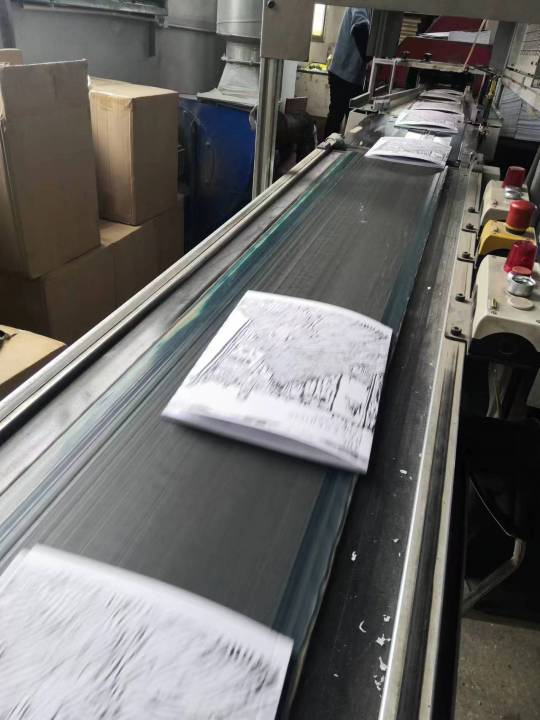

Photo

Printing, binding, packing. The Necrophilic Landscape by Morgan Vogel. ed + design by Raighne.

—>PRE-ORDER • Ships July 11th 2023

“[A] solo masterpiece...one of the most stunning works of comics art in the last decade.” —Austin English, The Comics Journal

“...some might even say 'edited' by the forces of nature.” —Noel Freibert, Old Ground

#The Necrophilic Landscape#Morgan Vogel#2dcloud#big ticket#comics#altcomics#graphicnovels#yearbooks#printing

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

ICYMI -- Small Press Comics Criticism and Whatnot for 4/24/17 to 4/30/17

ICYMI — Small Press Comics Criticism and Whatnot for 4/24/17 to 4/30/17

Highlighting some great small press comics criticism being published, as well as other random things that have caught my eye over the past week.

COMICS CRITICISM

* Greg Hunter talks about THE NECROPHILIC LANDSCAPE by Tracy Auch, “a bracing work, compelling both in spite of and because of its incompleteness.”

* Alex Hoffman reviews BOOK OF VOID by Viktor Hachmang, a book which asks “a specific…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Photo

The Necrophilic Landscape

Morgan Vogel

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

ICYMI -- Small Press Comics Criticism and Whatnot for 4/24/17 to 4/30/17

ICYMI — Small Press Comics Criticism and Whatnot for 4/24/17 to 4/30/17

Highlighting some great small press comics criticism being published, as well as other random things that have caught my eye over the past week.

COMICS CRITICISM

* Greg Hunter talks about THE NECROPHILIC LANDSCAPE by Tracy Auch, “a bracing work, compelling both in spite of and because of its incompleteness.”

* Alex Hoffman reviews BOOK OF VOID by Viktor Hachmang, a book which asks “a specific…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Greg Hunter reviews The Necrophilic Landscape by Tracy Auch

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tracy Auch, 2016

Why did you release The Necrophilic Landscape as you did, with the color removed and the title changed?

“The Necrophilic Landscape” was composed in 2010 and then shelved after being rejected for a grant. At that time the author was influenced by gothic and genre literature such as Melmoth the Wanderer and The Devil’s Elixirs, or Edogawa Ranpo’s Detective Stories. In my personal work I try to avoid nostalgia in the use of these generic references to male authors. I was asked to edit “The Necrophilic Landscape” and turn it into something suitable for release. I chose to foreground a theme that was only partially worked out in the original, that is-- that the narrative takes place in an almost entirely male world. The most obstructive editorial decision I made was to remove a central passage which contained the original’s only depiction of sex or a female character. The printed version of the book is more disjointed as a result of this decision, but it seemed to me that the only explanation for the narrative’s total mystification of sexual reproduction could be that it takes place in a fantasy world that contains only men and male children. The change in title reflects my critical distance as an editor and was meant to refer to a concept employed by a feminist theorist I like of a male drive towards necrophilia (versus female ‘biophilia’). I believe the color was removed because scans of the original artwork were not available.

What do you think of underground comics?

I’m interested in what it means for there to be a cultural or political “mainstream” against which can be defined various subcultures or genres or fringe political movements. In terms of my critical perspective on my own history, I feel like emotional investment in “subculture”, such as underground comics, or punk, or the cultural aspects of certain forms of leftist or queer or feminist political organizing, can express avoidance towards deeper questions of a person’s political role or subjectivation within a political system. By sending off social signals that I am part of and accepted in some form of fringe culture or another, I can maybe elide or make myself seems separate from aspects of my subjectivation that make me feel uncomfortable. And I might even feel emotionally justified in doing this, since it feels unfair to be implicated in a political and biological reality in which I never asked to take part. Of course then I’m diverting my energy into the symbolic and away from the material. I would like to counteract this tendency by being as “mainstream” as I can as a cultural producer but I doubt my art can change anything. My participation in political strategies of seperatism and “fringe-ism” seems separate to me from my practice as an artist.

How do you feel about the way in which you’ve been accommodated so far?

I feel like my peers have been very gracious in accommodating me as an artist despite the intensity of my specific needs and my constant undermining of my own practice. I still feel bitterness and feel excluded, although I am aware I mostly choose to exclude myself . I don’t represent myself as an artist on social media but I watch what other people are doing, and I feel special bitterness about the significance and complexity with which some of my artistic peers are able to implicate their bodies or personalities in their practice, versus my need for invisibility and my feeling that my showing my body would be pathetic. I feel conflicted in this desire to remove my body from my practice, versus my awareness that there is nothing significant or new to say at this moment that does not implicate the body and that the dematerialization of the body is a page or archetypal feint of patriarchal discourse. I often feel the desire to express myself as if I were someone else.

- Tracy Auch / Morgan Vogel / Caroline Hennessy / Caroline Bren

39 notes

·

View notes