#the dawn of everything

Text

times, places, and practices that I want to learn from to imagine a hopeful future for humanity 🍃

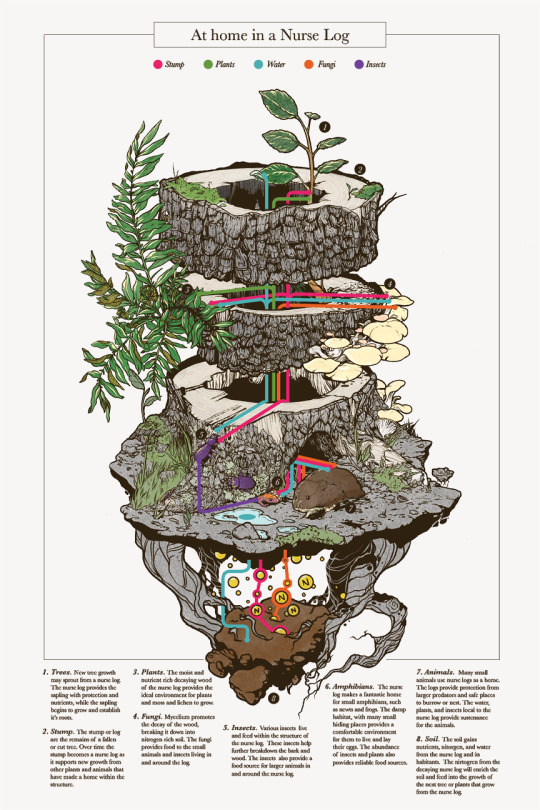

the three sisters (squash, beans, maize) stock photo - alamy // anecdote by Ira Byock about Margaret Mead // art by Amanda Key // always coming home by Ursula K. Le Guin // Yup'ik basket weaver Lucille Westlock photographed by John Rowley // the left hand of darkness by Ursula K. Le Guin // photo by Jacob Klassen // the carrier bag theory of fiction by Ursula K. Le Guin // article in national geographic // the dawn of everything by David Graeber and David Wengrow // braiding sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer // the birchbark house by Louise Erdrich // photo by John Noltner

I'm looking for more content and book recs in this vein, so please send them my way!

#solarpunk#hopepunk#braiding sweetgrass#just a collection of books and pictures that make me hopeful for the future#margaret mead#robin wall kimmerer#nature#ursula k le guin#ursula k. le guin#the left hand of darkness#the carrier bag theory of fiction#the dawn of everything#anthropology#future#hopecore#native plants#biodiversity#sustainability#eco#eco friendly#louise erdrich#civilization

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

The most common mistake people make when thinking about prehistory and how to avoid it.

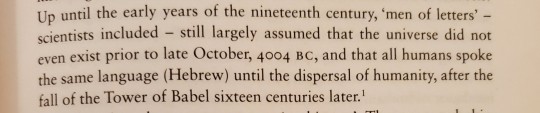

In "The Dawn of Everything, A New History for Humanity" David Graeber gives what I think might be the best piece of advice I've ever heard for understanding deep human history, and that is to get your mind out of the Garden of Eden.

People speculating about prehistory before modern archeology were quick to frame early humanity as existing in a "state of nature", either with pure innocent tribal communism, or being brutish barbarous cavemen, then something happened to bring us from the state of nature into "society". Did we make a Faustian bargain by domesticating plants and animals? Why is evidence of intergroup violence in prehistory so rare? How did we fall from the innocent state of nature? This, of course, smacks of the biblical creation story, so even if people don't believe it literally, they seem to have a hard time letting go of it spiritually even in a secular context.

This is pretty much nonsense, of course. Humans have existed for over 2 million years. Anatomically modern humans have existed for at least 300 thousand years. Behaviourally modern humans (with symbolism, art, long distance trade, political awareness) have existed for at least 50 thousand years, from our best evidence, but possibly a lot longer. The time between the Sumerians inventing writing and urban living 5,000 years ago and now is only a narrow slice of human history.

If we want to understand human history properly, we shouldn't understand people of the past as fundamentally different from us. They were intelligent, politically aware people doing their best in the world they found themselves in, just like we are today. We didn't fall from innocence with the development of behavioral modernity, religion, farming, war, money, capitalism, computers, or anything else. The world has changed a lot, but people have been experimenting with different ways to live for as long as there have been people, like this example I've posted before about disabled people's role in late pleistocene Eurasian society.

People have been the same as we are now for at least the last 50 thousand years. We have lived in countless different ways and will continue to experiment. There was no fall, and we don't live at the end of history.

363 notes

·

View notes

Text

Individual houses were typically in use for between fifty and 100 years, after which they were carefully dismantled and filled in to make foundations for superseding houses. Clay wall went up on clay wall, in the same location, for century after century, over periods reaching up to a full millennium. Still more astounding, smaller features such as mud-built hearths, ovens, storage bins and platforms often follow the same repetitive patterns of construction, over similarly long periods. Even particular images and ritual installations come back, again and again, in different renderings but the same locations, often widely separated in time....

as individual houses built up histories, they also appear to have acquired a degree of cumulative prestige. This is reflected in a certain density of hunting trophies, burial platforms and obsidian - a dark volcanic glass, obtained from sources in the highlands of Cappadocia, some 125 miles north. The authority of long-lived houses seems consistent with the idea that elders, and perhaps elder women in particular, held positions of influence. But the more prestigious households are distributed among the less, and do not appear to coalesce into elite neighborhoods.

a description of Çatalhöyük, a neolithic city from 7,400 bc. from the dawn of everything, by davids: graeber and wengrow.

this city remained settled for 1,500 years - "roughly the same period of time that separates us from amalafrida, queen of the vandals in .. ad 523"

#eezordalf's wisdom#the dawn of everything#david graeber#david wengrow#anthropology#paleoanthropology#books#prehistory#neolithic#Çatalhöyük#catalhoyuk#history#unfocus your eyes and let the vast maw of time take you#wizardblr#wizardposting

597 notes

·

View notes

Text

The freedom to abandon one’s community, knowing one will be welcomed in faraway lands; the freedom to shift back and forth between social structures, depending on the time of year; the freedom to disobey authorities without consequence – all appear to have been simply assumed among our distant ancestors, even if most people find them barely conceivable today. Humans may not have begun their history in a state of primordial innocence, but they do appear to have begun it with a self-conscious aversion to being told what to do. If this is so, we can at least refine our initial question: the real puzzle is not when chiefs, or even kings and queens, first appeared, but rather when it was no longer possible simply to laugh them out of court.

The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity by David Graeber and David Wengrow

#the dawn of everything#David Graeber#David Wengrow#archeology#prehistory#anthropology#history#upper paleolithic#paleolithic#human history#sociology#book recommendations#book quotes#nonfiction#readings#reading list#reading recommendations#book rec#cultural anthropology#history of science#inequality#anarchism#writings

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Most people today believe they live in free societies (indeed, they often insist that, politically at least, this is what is most important about their societies), but the freedoms which form the moral basis of a nation like the United States are, largely, formal freedoms.

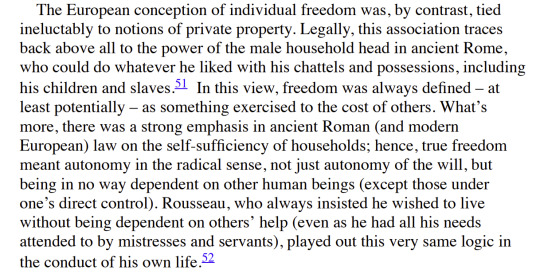

American citizens have the right to travel wherever they like – provided, of course, they have the money for transport and accommodation. They are free from ever having to obey the arbitrary orders of superiors – unless, of course, they have to get a job. In this sense, it is almost possible to say the Wendat had play chiefs and real freedoms, while most of us today have to make do with real chiefs and play freedoms. Or to put the matter more technically: what the Hadza, Wendat or ‘egalitarian’ people such as the Nuer seem to have been concerned with were not so much formal freedoms as substantive ones. They were less interested in the right to travel than in the possibility of actually doing so (hence, the matter was typically framed as an obligation to provide hospitality to strangers). Mutual aid – what contemporary European observers often referred to as ‘communism’ – was seen as the necessary condition for individual autonomy.

From The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity (2021), by anthropologist David Graeber and archaeologist David Wengrow

#history#world history#politics#political science#sociology#communism#anarchism#anthropology#archaeology#freedom#mutual aid#equality#philosophy#human rights#the dawn of everything#david graeber#david wengrow#quote#quotes#book quotes#wendat#native american#first nations

349 notes

·

View notes

Text

So what was really new here? Let’s go back to the archaeological evidence. Settlements inhabited by tens of thousands of people make their first appearance in human history around 6000 years ago, on almost every continent, at first in isolation. Then they multiply. One of the things that makes it so difficult to fit what we now know about them into an oldfashioned evolutionary sequence, where cities, states, bureaucracies and social classes all emerge together, is just how different these cities are. It’s not just that some early cities lack class divisions, wealth monopolies, or hierarchies of administration. They exhibit such extreme variability as to imply, from the very beginning, a conscious experimentation in urban form.

Contemporary archaeology shows, among other things, that surprisingly few of these early cities contain signs of authoritarian rule. It also shows that their ecology was far more diverse than once believed: cities do not necessarily depend on a rural hinterland in which serfs or peasants engage in back-breaking labour, hauling in cartloads of grain for consumption by urban dwellers. Certainly, that situation became increasingly typical in later ages, but in the first cities small-scale gardening and animal-keeping were often at least as important; so too were the resources of rivers and seas, and for that matter the continued hunting and collecting of wild seasonal foods in forests or in marshes. The particular mix depended largely on where in the world the cities happened to be, but it’s becoming increasingly apparent that history’s first city dwellers did not always leave a harsh footprint on the environment, or on each other.

David Graeber and David Wengrow, The Dawn of Everything

107 notes

·

View notes

Text

The more rosy, optimistic narrative – whereby the progress of Western civilization inevitably makes everyone happier, wealthier and more secure – has at least one obvious disadvantage. It fails to explain why that civilization did not simply spread of its own accord; that is, why European powers should have been obliged to spend the last 500 or so years aiming guns at people’s heads in order to force them to adopt it.

David Graeber and David Wengrow, The Dawn of Everything, p.493

325 notes

·

View notes

Text

On “Civilization” from The Dawn of Everything

One problem is that we’ve come to assume that ‘civilization’ refers, in origin, simply to the habit of living in cities. Cities, in turn, were thought to imply states. But as we’ve seen, that is not the case historically, or even etymologically. The word ‘civilization’ derives from Latin civilis, which actually refers to those qualities of political wisdom and mutual aid that permit societies to organize themselves through voluntary coalition. In other words, it originally meant the type of qualities exhibited by Andean ayllu associations or Basque villages, rather than Inca courtiers or Shang dynasts. If mutual aid, social co-operation, civic activism, hospitality or simply caring for others are the kind of things that really go to make civilizations, then this true history of civilization is only just starting to be written.

As we’ve been showing throughout this book, in all parts of the world small communities formed civilizations in that true sense of extended moral communities. Without permanent kings, bureaucrats or standing armies they fostered the growth of mathematical and calendrical knowledge. In some regions they pioneered metallurgy, the cultivation of olives, vines and date palms, or the invention of leavened bread and wheat beer; in others they domesticated maize and learned to extract poisons, medicines and mind-altering substances from plants. Civilizations, in this true sense, developed the major textile technologies applied to fabrics and basketry, the potter’s wheel, stone industries and beadwork, the sail and maritime navigation, and so on.

A moment’s reflection shows that women, their work, their concerns and innovations are at the core of this more accurate understanding of civilization. As we saw in earlier chapters, tracing the place of women in societies without writing often means using clues left, quite literally, in the fabric of material culture, such as painted ceramics that mimic both textile designs and female bodies in their forms and elaborate decorative structures. To take just two examples, it’s hard to believe that the kind of complex mathematical knowledge displayed in early Mesopotamian cuneiform documents or in the layout of Peru’s Chavín temples sprang fully formed from the mind of a male scribe or sculptor, like Athena from the head of Zeus. Far more likely, these represent knowledge accumulated in earlier times through concrete practices such as the solid geometry and applied calculus of weaving or beadwork. What until now has passed for ‘civilization’ might in fact be nothing more than a gendered appropriation – by men, etching their claims in stone – of some earlier system of knowledge that had women at its centre.

—The Dawn of Everything, Graeber and Wengrow

#civilization#history#anthropology#archaeology#political philosophy#human nature#sharing because I love this so much and need everyone to read it 🥲#finally some good fucking food#these guys spend the entire first chapter absolutely tearing apart all the enlightenment thinkers theories about social evolution#the dawn of everything

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Ever since Adam Smith, those trying to prove that contemporary forms of competitive market exchange are rooted in human nature have pointed to the existence of what they call 'primitive trade'. Already tens of thousands of years ago, one can find evidence of objects — very often precious stones, shells or other items of adornment — being moved over enormous distances. Often these were just the sort of objects that anthropologists would later find being used as 'primitive currencies' all over the world. Surely this must prove capitalism in some form or another has always existed?

"The logic is perfectly circular. If precious objects were moving long distances, this is evidence of 'trade' and, if trade occurred, it must have taken some sort of commercial form; therefore, the fact that, say, 3,000 years ago Baltic amber found its way to the Mediterranean, or shells from the Gulf of Mexico were transported to Ohio, is proof that we are in the presence of some embryonic form of market economy. Markets are universal. Therefore, there must have been a market. Therefore, markets are universal. And so on.

"All such authors are really saying is that they themselves cannot personally imagine any other way precious objects might move about. But lack of imagination is not itself an argument... In fact, anthropology provides endless illustrations of how valuable objects might travel long distances in the absence of anything that remotely resembles a market economy."

�� The Dawn of Everything, David Graeber and David Wengrow, p.22

325 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've said it before and I'll say it again, The Dawn of Everything by David Graeber and David Wengrow is basically nonfiction Good Omens.

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

from The Dawn of Everything

#repost of someone else’s content#the dawn of everything#graeber#wengrow#patriarchy#class society#adultism#child abuse#history

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I love this quote. It is exactly what I needed to read at this moment. It segues beautifully with these lines from The Dawn of Everything. Our false certainty about the past feeds our false certainty about the inevitability of an apocalyptic future.

#The Dawn of Everything#history#anthropology#David Graeber#David Wengrow#human history#social existence

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

This book continues to eff me up.

We know that basket weaving and other textile work has been considered "women's work" historically.

We also know that edible plants and uses of plants for textile work has been introduced side by side.

So it would be reasonable to believe that women were the 'scientists' conducting this "plant science".

Like i never thought to extend that line of logic.

Obviously this is more nuanced and complex but that shook my gendered assumptions of agriculture, cultivation, botany, and farming.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

We should also consider if the inhabitants of the mega-sites consciously managed their ecosystem to avoid large-scale deforestation... Archaeological studies of their economy suggest a pattern of small-scale gardening, often taking place within the bounds of the settlement, combined with the keeping of livestock, cultivation of orchards, and a wide spectrum of hunting and foraging activities. The diversity is actually remarkable, as is its sustainability. As well as wheat, barley, and pulses, the citizens' plant diet included apples, pears, cherries, sloes, acorns, hazelnuts and apricots. Mega-site dwellers were hunters of red deer, roe deer, and wild boar as well as farmers and foresters. It was 'play farming' on a grand scale: an urban populous supporting itself through small-scale cultivation and herding, combined with an extraordinary array of wild foods.

This way of life was by no means 'simple'. As well as managing orchards, gardens, livestock and woodlands, the inhabitants of these cities imported salt in bulk from springs in the eastern Carpathians and the Black Sea littoral. Flint extraction by the ton took place in the Dniestr valley, furnishing material for tools. A household potting industry flourished, its products considered among the finest ceramics of the prehistoric world; and regular supplies of copper flowed in from the Balkans. There is no firm consensus from archaeologists about what sort of social arrangements all this required, but most would agree the logistical challenges were daunting. A surplus was definitely produced, and with it ample potential for some to seize control of the stocks and supplies, to lord it over others or battle for the spoils; but over the eight centuries we find little evidence for warfare or the rise of social elites.

a description of talianki (located in modern day ukraine), a neolithic site from 5,700 years ago (inhabited from roughly 4100 to 3300 bc) from the dawn of everything by davids: graeber and wengrow

once again this book is fantastic - and one of its main theses is that "the agricultural revolution" and some of the conclusions we draw from it are, largely, not true.

the development of farming in human societies is a much much longer and more "playful" process than popular narratives would have us believe. 'agricultural revolution' suggests an on/off switch almost. and the way it's usually taught sees agriculture being "invented" and then spreading like wildfire to take over the globe - only then allowing for true cities and the "necessary evils" they entail. this simply isn't true. an urban, farming society is not automatically doomed to bureaucracy, inequality, and exploitation.

all across the world the archaeological evidence points to the domestication of plants taking literal thousands of years longer than it "ought to." and then, even when the domestication of a wild plant was complete there isn't an immediate rise of huge fields and class stratification (as the popular narrative goes). again - in the magnitude of multiple thousands of years. we have generations upon generations of humans with farming know-how who don't immediately begin a march of politics and inequality precipitated by farming.

agriculture isn't humanity's curse no matter what the memes and capitalists say. we are not doomed to our current ways - we can imagine, we can build, we can create new ways of being. the past is the present is the past. and fuck you capitalism and doomed "human nature" debates. and read the dawn of everything <3

#eezordalf's wisdom#anthropology#david graeber#david wengrow#books#history#wizardblr#wizardposting#the dawn of everything#talianki#ukraine#archaeology#neolithic#prehistory#studying my tomes#humanity i love you#the human condition#human experience

205 notes

·

View notes

Text

Colonial appropriation of indigenous lands often began with some blanket assertion that foraging peoples really were living in a State of Nature – which meant that they were deemed to be part of the land but had no legal claims to own it. The entire basis for dispossession, in turn, was premised on the idea that the current inhabitants of those lands weren’t really working. The argument goes back to John Locke’s Second Treatise of Government (1690), in which he argued that property rights are necessarily derived from labour. In working the land, one ‘mixes one’s labour’ with it; in this way it becomes, in a sense, an extension of oneself. Lazy natives, according to Locke’s disciples, didn’t do that. They were not, Lockeans claimed, ‘improving landlords’ but simply made use of the land to satisfy their basic needs with the minimum of effort. James Tully, an authority on indigenous rights, spells out the historical implications: land used for hunting and gathering was considered vacant, and ‘if the Aboriginal peoples attempt to subject the Europeans to their laws and customs or to defend the territories that they have mistakenly believed to be their property for thousands of years, then it is they who violate natural law and may be punished or “destroyed” like savage beasts.’ In a similar way, the stereotype of the carefree, lazy native, coasting through a life free from material ambition, was deployed by thousands of European conquerors, plantation overseers and colonial officials in Asia, Africa, Latin America and Oceania as a pretext for the use of bureaucratic terror to force local people into work: everything from outright enslavement to punitive tax regimes, corvée labour and debt peonage.

From The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity (2021), by anthropologist David Graeber and archaeologist David Wengrow

#the dawn of everything#david graeber#david wengrow#history#world history#colonialism#settler colonialism#imperialism#genocide#european colonialism#john locke#locke#archaeology#anthropology#quote#book quotes#native american

6 notes

·

View notes