#the best I can do is give basic info and then hyperspecific information about one character in the whole franchise

Text

Someone: * is very passionate about a certain topic and can tell a lot of info/lore *

Me:

#im very bad at knowing stuff#the best I can do is give basic info and then hyperspecific information about one character in the whole franchise#two if we're pushing it sjxhsksbjx#like I rlly wanna get into warhammer 40k lore but after a bit of reading on the chaos gods I got a headache from the walls of text#need to find a podcast or yt series cause I absorb info way better that way#thats what I get for watching a shit ton of rubixraptor vids#only once did I know a lot for a thing (but not as much as I thought) but once I left that interest I could never fill it again#f

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

How to write a five paragraph essay

This is going to be my third and last of these posts, unless people have questions that arise from them (at which point I am more than happy to make more - just let me know!) You can find my post about writing thesis statements here, and my post on essay conclusions here (both imbedded). Unlike my previous posts, this is going more in-depth about five paragraph essays, though I imagine you can take the tips here and apply them elsewhere.

Alrighty guys. Strap in because this one’s gonna be a bit long.

1) Prewriting

Okay. Since I hate prewriting as a concept (seriously. You do all this work and you don’t have any essay to show for it? what is this?), I tend to keep it pretty short and sweet, but it is necessary.

What do do?

Read through your source material, and get an understanding of what you’re going to argue about

As you’re reading, make sure you write down your sources or else doing your bibliography is going to be a pain (just copy/pasting urls should suffice at this point)

Create an argument (generally, what is the point you’re trying to get across)

Write your thesis. It’s important that you do this AFTER reading the material, as you won’t know what to argue if you come up with a thesis before doing the reading. Constructing your thesis is also important to do before you actually get to writing, as it informs a lot of the structure of the essay. For more info on how to construct a thesis, I made this post as part of this mini series not too long ago (same link as above).

Outline your essay. This can be detailed if you like it like that, or it can just be a few words for each paragraph. As I personally find outlines to be both necessary and a pain, I tend to go with the latter of the two (described further in the example below). However, experiement with both - some people work better when they have detailed outlines with all of their sources and arguments listed under each paragraph heading.

How to outline

(How to outline, as well as how to write the intro paragraph, body paragraphs, a link to how to write conclusion paragraphs, and general tips all under the cut)

As you may have guessed, there are a number of ways to outline. The most basic looks like this:

Paragraph 1: Intro

Paragraph 2: [insert topic 1]

Paragraph 3: [insert topic 2]

Paragraph 4: [insert topic 3]

Paragraph 5: Conclusion

From here, you can make things more and more detailed if you like. Some common things people put in outlines are:

evidence presented

points made

relevant sources for each paragraph

their topic sentence

etc...

My advice is to play around and see what works best for you. If you’re like me and really really hate prewriting, you may go with a simpler approach. Or, if you find drafting to be hell on earth, maybe put more time into prewriting to make drafting faster.

2) Introduction

This is arguably the most important part of your essay (at least, that’s what my middle school teachers always said). The common difficulty is that everyone seems to be saying how important it is, and how cructial it is, and how [insert synonym for important and crutial] it is, and all that jazz. Which means after a twenty minute lecture of WHY you should write an introduction, there never seems to be enough time to teach people how to actually WRITE it.

Here’s the thing. The point of your intro is to ease your reader into the topic. You don’t want to blind side them with something hyperspecific out of the blue. At the same time, you don’t want them to loose interest because you’re taking too long.

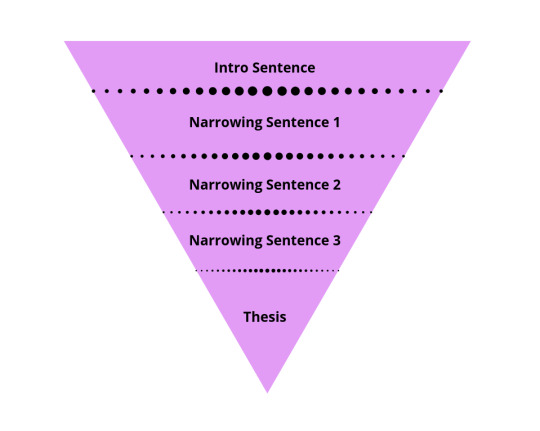

The trick is to use the funnel method.

It works like this: each sentence is a layer, and how wide the funnel is represents how broad your statement is. Your first statement is going to be huge - something that encompases a lot. Each sentence should encompass less and less, until you get to your thesis, which is very narrow.

A formula I frequently use (depending on if it’s applicable) is:

Intro: Sentence about humanity as a whole (establishes basic concept)

NS 1: Sentence that establishes that Intro thing applies to certain time/place (establishes the what/where)

NS 2: Sentence that specifies how, exactly, Intro thing applies to time/place (establishes how)

NS 3: Sentence that specifies relevant groups within this time and place

Thesis: the specific thing I am arguing.

In this (very generic, and also very fake) example, I’m going to bold every other sentence so they are easy to distinguish from one another. It’s the same pattern featured above.

Conflict is one of the universal truths of life. Throughout the ages, individuals and groups have found themselves on opposing sides of a disagreement, but few could compare to the 1789 B.C. Battle of the Frogs in what is now modern-day Tatooine. Dissention had been brewing for years, but when the Narnians finally stole all of native unicorns, the civillians of the sandy outer-rim planet finally hit a tipping point; they were prepared to sacrifice anything if it meant being free. Despite the epic proportions of the Battle, a few individuals were able to record the events of the conflict in journals that have survived to this day. In his journal “Of life on the Desert,” Percy Jackson describes the effects of war, including the impact it had on his family, his work, and the state of his village.

3) Body Paragraphs

These three paragraphs are where you will be backing up your thesis statement. This is a fair bit of space, to work with if you do it right, but it’s also not a lot of space, so you do have to make sure to use it wisely. An easy way to make sure you’re doing this right is to.....

Follow yet MORE paragraph formulas

(yay!)

Seriously though. Using formulas in your essays will set you free, and it makes it look like you know what you’re doing.

Sentence 1: Topic Sentence

This is usually going to start out with some kind of transition phrase such as “in addition to [previous thing]” or whatever. Then it’s going to introduce the thing you’re actually going to talk about in this paragraph.

Sentence 2 - Second to Last: Evidence and Analysis

For each paragraph, you’re probably going to want between three and four pieces of evidence (as two looks like there’s not actually solid evidence, and five becomes tedious).

For this structure, you’re going to want to spend a sentence introducing a piece of evidence, making sure to include the proper in-text citations (which I am not going to cover here, but I can cover in another post if someone asks me to).

After your evidence citation, you’re going to want to write at least one or two sentences of analysis, either picking apart just that piece of evidence, or linking that evidence to other pieces of evidence. For beginners, many teachers will expect about one line of analysis, from about sophomore year of highschool up, teachers begin to expect two or more.

Make sure that your evidence and analysis flows together - that is, organize your evidence into a logical order, and use transition words (there’s huge lists out there - google is your friend) to go from an analysis sentence to another piece of evidence.

Sentence 3 - Conclusion Sentence

This is one of the harder sentences to nail, but the idea is that you want to restate what your topic sentence is.

If you can’t think of a good conclusion sentence, you can write a transition sentence instead, and on the topic sentence of your next paragraph, leave off the transition.

4) Conclusions

I already did a post on conclusions, which is linked here (imbedded).

5) Miscellaneous Tips!

Never use “you” statements. This is because you can never be sure of your reader’s background, so it wrecks some of the credibility of your argument! If you’re describing something and you feel a burning urge to write “you might do X” or something along those lines, switch “you” out for the word “one”

Similarly, never use I statements. They make things look like opinions rather than facts. NOT GOOD. A good fix is to not use personal experiences that would force you to use I statements (unless explicitely asked to), and to cut off all phrases such as “I think” or “I researched.” These are implied, and you make your argument look stronger without them.

Avoid using the word “that.” If you can cut it out and the sentence still makes sense, cut it. It’ll make your narrative voice stronger.

If you need to make your essay look longer, find places where paragraphs end at the end of a line. Then, throughout the paragraph, un-abbreviate words that can be sensably un-abbreviated. This will push a few words onto the next line and give the apperance of a longer essay.

Similarly, if you want your essay to appear shorter (if you have a page limit or something), look for places where a paragraph just barely makes it onto a new line, and cut extra words so that the words move back until that new line isn’t there.

Keep track of all new sources as you go - it saves so much time.

Make in-text citations as you go, rather than trying to put them in after the fact.

Run spell check before turning in your work

Make sure your grammar is correct, and understand how to use colons and semi-colons (they will save your life)

Now, here are 1000 awesome points for reading until the end, and good luck with your essay!

#writing#writeblr#studyblr#writers on tumblr#school papers#essays#thesis statements#introductions#conclusions#body paragraphs#english#language arts#homework#schoolwork#olive’s writing vibes

19 notes

·

View notes