#tachibana hina render

Photo

#ken renders#ken renders hina tachibana#tokyo revengers#tokyo revengers hina#tokyo revengers hina tachibana#hina tachibana#hina tachibana render#tokyo revengers render#tachibana hina#tachibana hina render#female anime render#image anime render

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 2 (26): (1587) Third Month, Third Day, Midday.

26) Third Month, Third Day; Midday¹.

It was agreed that [only] kashi [would be served]².

◦ 4.5-mat [room]³.

◦ [Guests:] Jōko [紹古]⁴, Sōkei [宗惠]⁵.

[Sho [初].]⁶

﹆ Shunkyo [舜擧]⁷, painting of peach[-blossoms]⁸.

◦ Bon-san [盆山] Kiji [紀路]⁹.

◦ Kiri-gama [桐釜], [suspended on the] small[-linked] chain¹⁰.

◦ On the kyū-dai [弓臺]¹¹:

below:

﹆ mizusashi mu-mon [水指 無紋]¹²;

﹆ momo-jiri [モヽ尻]¹³;

﹆ kuchi-boso [口細]¹⁴;

﹆ guru-guru [クル〰]¹⁵;

◦ fukusa [服サ]¹⁶;

above:

◦ On a kō-bon [香盆]¹⁷: kōro Usu-gumo [香爐 薄雲]¹⁸, kōgō futae ao-gai [香合 二重青貝]¹⁹, kyōji-tate [キヤウシ立]²⁰;

◦ Habōki [羽帚]²¹.

After the kōro was passed around, a set of charcoal [was laid in the ro]²².

▵ Sakemono ju-ju [サケ物重〻]²³.

▵ Yomogi no mochi [ヨモキノモチ]²⁴.

▵ Nimono [煮物] tori ・ kushi-awabi ・ shiitake ・ mame ・ musubi-me [鳥 ・ 串アハヒ ・ 椎茸 ・ マメ ・ ムスヒメ]²⁵.

▵ Mizu-kuri [水栗]²⁶.

▵ Sake, two rounds.

Go [後]²⁷.

◦ The toko [was left] as it was.

◦ Kyū-dai [弓臺]:

below:

◦ as it was;

above:

﹆ chaire sasa-mimi [茶入 サヽ耳]²⁸;

◦ on a naka-bon [中盆]²⁹: natsume ・ kasane-chawan ・ ori-tame [ナツメ ・ カサネ茶碗 ・ 折タメ]³⁰.

_________________________

¹San-gatsu mikka, hiru [三月三日、晝].

The Gregorian date of this chakai was April 10, 1587. It was thus nearly high spring, and the earliest of the cherry blossoms would have been getting ready to open.

The occasion for this chakai was the Momo-no-seku [桃の節句], or peach-blossom festival (hence the kakemono). The occasion was also known as the Hina-matsuri [雛祭り], because on this day the girls of the household displayed their collection of hina-ningyō [雛人形] -- small dolls that were dressed and arranged to reproduce the scene of the Imperial court.

Because the morning was occupied with inspecting the dolls (many of which were precious antiques -- especially in the households of the wealthy machi-shū), and partaking of a morning meal replete with festive delicacies, Rikyū and his guests agreed beforehand to limit the food served during this chakai to kashi only (according to his notation).

Rikyū uses an impressive set of utensils, but his focus seems to be on the Peach Festival aspect of the day.

²Kashi ni te, yakusoku [菓子ニて、約束].

That is, he arranged with the guests beforehand that he would only serve kashi. (Though the selection of kashi actually seems at least as substantial as many of his fuller kaiseki -- probably to give the kama time to return to a boil after a new set of charcoal had been added to the fire, while making it clear that the limitation to kashi only was not a sign of parsimony.)

This gathering is what is now called a kashi-chaji [菓子茶事]. Whether it was also an impromptu chakai (as Shibayama Fugen suggests) cannot be known -- Rikyū does not mention when the agreement over the kashi was made -- though the rather large number of different kinds of kashi (most of which were cooked, and some of which required several hours of preparation time) served, along with the special utensils that Rikyū used, argues against this.

³Yojō-han [四疊半].

This was the 4.5-mat room in Rikyū's residence.

He is still in Sakai.

⁴Jōko [紹古].

Nothing is known about this person*.

That said, however, it is important to point out that both Shibayama Fugen and Tanaka Senshō give a different name: Jōsa [紹佐]†.

Jōsa [紹佐] would refer to the man known as Abura-ya Jōsa [油屋紹佐], the wealthy Sakai machi-shū and chajin who appears to have been a disciple of Jōō. Some scholars identify this person with the man who affected the (Japanese-style) name Date Jōyū [伊達常祐; ? ~ 1579] -- though, given the fact that the present gathering took place in 1587, this could not be him. Perhaps Jōsa was Jōyū’s son‡. The wealthy Abura-ya [油屋] firm, which dealt in oils, was headquartered in Sakai.

At any rate, in addition to his being mentioned several times as a guest in Rikyū's several kaiki, Jōsa is also said to have been closely connected to Kokei oshō -- and presented the monk with thirty strings of coins** for expenses when Kokei moved from Sakai to the Daitoku-ji in Kyōto.

__________

*This name is found only in the Enkaku-ji version of Book Two of the Nampō Roku (and in Kumakura Isao's modern Japanese rendering, which more or less follows the Enkaku-ji text).

Neither Hisamatsu Shin-ichi (the editor of the Sadō Koten Zen-shu [茶道古典全集] edition of the Enkaku-ji text), nor Kumakura Isao, do any more than list this name without comment.

The fact that the other manuscripts generally agree on a different name (as has been mentioned before, Tanaka Senshō had access to Jitsuzan's original notes -- the same notes from which Jitsuzan himself copied) suggests that Tachibana Jitsuzan may have made a mistake when he transcribed this kaiki from his notes into the notebook that he was preparing for presentation to the Enkaku-ji.

†Tanaka Senshō also includes a note suggesting that some other copies give the name as Jōrin [紹林] -- though he seems to feel that this is not credible.

Jōrin [紹林] would refer to Tateishi Jōrin [立石紹林; his dates of birth and death unknown], another machi-shū chajin from Sakai, who had apparently studied chanoyu with Jōō (as attested to by his name). Jōrin was a guest at chakai that Rikyū gave on the 25th of the Second Month, the 26th day of the Twelfth Month of the previous year; and he is also mentioned as having introduced Maruyama Bansetsu [丸山晩雪] to Rikyū (Bansetsu was entertained by Rikyū on the 27th Day of the First Month), suggesting that Jōrin and Rikyū were close friends.

‡And so Jōsa would have assumed the name of Jōyū when he succeeded to the headship of the Abura-ya firm -- as was customary in many families during that period.

Jōyū certainly studied chanoyu from Jōō; but Jōsa is held, by certain scholars, to have been a disciple of Rikyū. This conundrum could be explained quite easily if the two were indeed father and son.

**“Zeni san-jū kanmon” [錢卅貫文]: 30,000 copper coins -- weighing some 112.5 kg.

⁵Sōkei [宗惠].

This was Mizuochi Sōkei [水落宗惠; his dates of birth and death are unknown], a respected machi-shū chajin from Sakai*. He is also said to have been the father of Rikyū's son-in-law, the man usually known as Sen no Jōji [千紹二]†.

Sōkei is mentioned as having been a guest at several other chakai that are recorded in Rikyū's kaiki (his most recent previous appearance having been on the 5th day of the Second Month, together with Kokei oshō and Nambō Sōkei‡), as well as in many other documents that have survived from this period.

__________

*Some suggest that he was also one of Rikyū's disciples (though it is more likely that he was a member of the group that formed around Rikyū in the years after Jōō’s death -- given Sōkei’s contemporary reputation as a chajin).

†He is usually known as Sen no Jōji because Rikyū adopted him into the Sen family upon his marriage to his daughter (a common enough practice at that time when a man had fathered few or no sons).

‡Implying that he may have been a member of their circle as well.

⁶Sho [初].

This notation, which means the shoza, is not found in the Enkaku-ji manuscript -- though both Tanaka Senshō's and Shibayama Fugen's manuscripts are so marked.

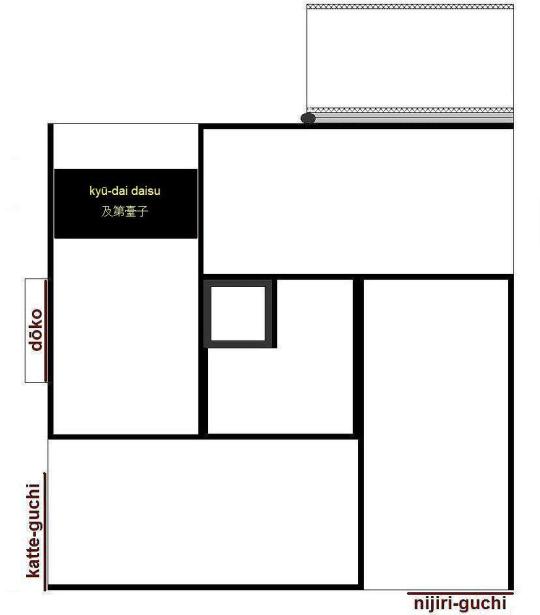

With respect to the kane-wari:

- the toko contained the kakemono, with a bon-san arranged on the floor in front of it, and so was chō [調];

- the room had the kama in the ro, meaning it was han [半];

- and as for the daisu, the kaigu were han [半] (because, while there were four objects, either the futaoki, or the koboshi, shared a kane with the shaku-tate), while the kō-bon and habōki on the ten-ita were chō [調] (each contacted yang-kane), giving a total of han [半] for the tana.

Chō + han + han is chō, which is appropriate for the shoza of a gathering held during the daytime.

⁷Shunkyo [舜擧].

Shùn-jǔ [舜擧] is one of the names used by the Chinese painter Qián Xuǎn [錢選; 1235 ~ 1305], who is also known as Yù-tán [玉潭], and who was active from the late Song into the early Yuan dynasty.

It is said that, though Qián Xuǎn was trained as a scholar, he did not succeed in advancing in the Song officialdom satisfactorily; while the collapse of the regime followed by the establishment of the Yuan dynasty, lead to a refusal to consider aiding the new overlords out of a sense of loyalty to Song (and so, China).

After 1276 Qián Xuǎn devoted himself to painting, and became famous for his realistic depiction of various textures (“fur and feathers”), as well as depictions of natural subjects. His works frequently display a nationalistic inclination, and harp back to the works of the Tang and Song dynasties.

⁸Momo[-no-]e [桃繪].

Among Qián Xuǎn's surviving paintings is one that is known as “a broken-off branch of peach blossoms” (Zhézhī táo-huā [折枝桃花]), shown below, though it is not certain whether this was the painting displayed by Rikyū on this occasion or not.

This painting, nevertheless, well illustrates Qián Xuǎn's technique.

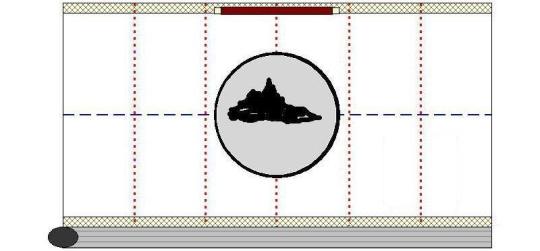

⁹Bon-san Kiji [盆山 紀路].

Kiji [紀路]* was the name of a famous bon-san [盆山]†. Below is a photograph of a different bon-san, known as Sue no matsu-yama [末ノ松山], which it may have resembled, arranged in the naka maru-bon [中丸盆] that was made for Ashikaga Yoshimasa by Haneda Gorō‡.

The Kiji viewing stone has never been located, if it still exists.

On this occasion it was displayed on the floor of the toko, in front of the scroll, as shown above.

__________

*This was the name of a road traversing the mountains, that was renowned for its scenic beauty, in the Province of Kii (Kii-no-kuni [紀伊の國]).

†Bon-san [盆山] means a mountain[-shaped stone] arranged in a tray. They are also known as bon-seki [盆石] (stones arranged on a tray), and sui-seki [水石] -- an abbreviation of the word sansui-seki [山水石], which means a landscape stone (that is, a stone whose shape evokes a landscape in miniature).

‡The original karamono naka maru-bon [中丸盆] was identical in size and shape to the tray seen in the photo. However, rather than being plain black lacquer, the Chinese tray had a brass plate (crafted to resemble a dragon) inlaid in the face, and a brass fuku-rin [覆輪] around the rim. While used for chanoyu (at the suggestion of the great dōbō [同朋] Nōami [能阿彌; 1397 ~ 1471]), the original tray seems to have been made for transporting hot dishes from the kitchens to the residential apartments (in China).

The original tray (along with the other five meibutsu trays) was lost when Yoshimasa's storehouse was destroyed by fire during the Ōnin wars.

In fact, many of these great treasures were originally mundane objects in their homelands; and their being esteemed in Japan suggests the lower technical level of native crafts, coupled with a fascination with the exotic.

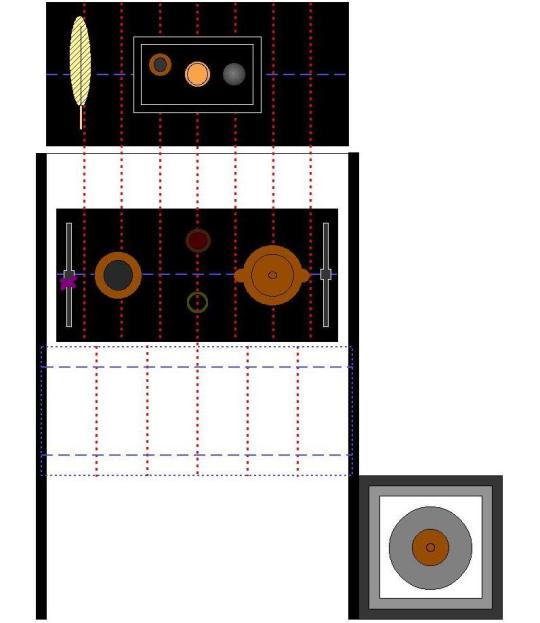

¹⁰Kiri-gama ko-kusari [桐釜 小クサリ].

This was the small kama, originally made for use with a small kimen-buro, that had formerly belonged to Jōō.

The kama was suspended over the ro on a chain with small links that has subsequently come to be known as Rikyū's azuki-kusari [小豆鎖].

This chain, along with Rikyū’s bronze tsuru and kan, is shown above.

¹¹Kyū-dai ni [弓臺ニ].

This refers to the kyū-dai daisu [及第臺子].

The ten-ita of this daisu is 2-shaku 9-sun 5-bu wide and 1-shaku 4-sun from front to back, while the ji-ita is 2-shaku 7-sun 5-bu wide and 1-shaku 3-sun deep. It, thus, can only be used in a room covered with kyōma-tatami and, because it has only two legs, it was originally not used with the furo (because the legs would interfere with the raising and lowering of the kimen-buro’s kan).

When arranged on the utensil mat, this daisu is placed 5-sun from the far end of the mat (rather than 4-sun 5-bu, as was the case with the shin-daisu), which means that there is 1-shaku 2-sun 5-bu between the upper corner of the ro and the front of the daisu. Consequently, the naka maru-bon [中丸盆] (which was 1-shaku 2-sun 3-bu in diameter) was the largest tray that can be used with this daisu.

¹²Mizusashi mu-mon [水指 無紋].

This was Rikyū's bronze mizusashi with kimen kan-tsuki [鬼面鐶付].

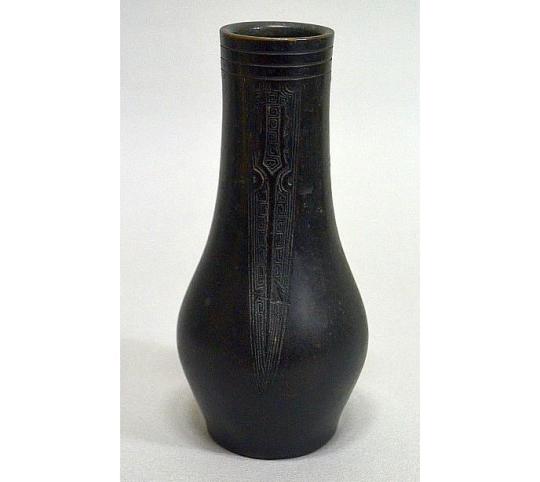

¹³Momo-jiri [モヽ尻].

This refers to the meibutsu hishaku-tate shown below.

Two kinds of momo-jiri shaku-tate are known from the time of Ashikaga Yoshimasa: one with bas relief decoration (shown above), and one without decoration (i.e., “mu-mon” [無紋], like the mizusashi)*. It is not known which of them Rikyū owned.

__________

*These pieces were originally made in pairs, for use as flower vases that were placed on the family altar. As this was something that almost every Chinese family had in the main sitting room of their house, both sorts of momo-jiri were easily available on the continent.

¹⁴Kuchi-boso [口細].

This was Rikyū's narrow-mouthed mizu-koboshi.

¹⁵Guru-guru [クル〰].

This was a ceramic ya-gaku [夜學] futaoki, probably of dark green ceramic (rather than the celadon shown in the photo).

The name suggests that the piece was etched with a stylus to look as if string had been coiled around it (before the openings were cut out). It has not been identified.

¹⁶Fukusa [服サ].

This was an ordinary temae-fukusa [手前袱紗]*. The fukusa, whatever its size, was folded in half, and then it was folded into thirds, as shown below†.

The fukusa was then knotted around the left leg of the daisu‡.

__________

*That said, it is actually not known what sort of cloth Rikyū used for his fukusa. Jōō and the chajin of his generation used Chinese donsu, of a size determined by the native width of the cloth from which it was made (people bought an entire roll of cloth, and made fukusa by cutting a length that was twice the width, which, when stitched, resulted in a not-quite-square wiping cloth); while Furuta Sōshitsu (and the tea men who came after him) used Japanese silk that was dyed dark purple. While this fukusa was copied from the small furoshiki that Rikyū used to wrap natsume of gift tea (and was identical to these in both size and color), it is unclear whether Rikyū eventually imitated Oribe's lead by using these cloths as temae-fukusa or not -- since surviving reports are contradictory, and should be considered propaganda intended to support the Edo period conventions espoused by the Sen families rather than historically accurate information.

The fukusa was (and, even in the present, should be) used for only one temae, and then discarded. And since it was a personal item, apparently none of Rikyū's ended up in any of his admirers' hands, and so none have survived.

†As always, the wasa [輪差] (the folded edge) is on the right, and the fukusa is folded in half away from you. Then the right hand slides from the upper corner to the lower one, so the wasa is in front, and at the top. Then the fukusa is folded in thirds, starting from the top (like a chakin).

‡The fukusa is held horizontally behind the leg of the daisu (with two folds at the bottom), and the knot is tied in front.

¹⁷Kō-bon ni [香盆ニ].

A “kō-bon” [香盆] could be any sort of tray that was large enough for the incense burner, kōgō, and (in this case) kyōji-tate [香筋建]* to fit on comfortably. In the present day small naga-bon (which does not conform with the dimensions of any of the classical trays described in the Nampō Roku) seem to be preferred by the modern schools, but in the classical period, square and round trays were used as well.

__________

*The kyōji-tate [香筋建] (it can also be written kyōji-tate [香箸立] -- though this form was considered rather inelegant) is like a miniature shaku-tate, in which the implements necessary for burning kyara [伽羅] incense in a hand-held censer are stood.

While the list may be abbreviated (and in the context of chanoyu, almost always is), the full set consist of:

- gin-yō-basami [銀葉挾] (a pair of pincers with flat heads that are used to handle the gin-yō [銀葉] -- mica squares on which the incense rests while being burned);

- kō-saji [香匙] (a sort of spoon used to scoop up the pieces of kyara when transferring them from the chopping block to the kōgō: incense wood is split into small pieces using a razor-sharp steel chisel, and the pieces are then handled with a special spoon in order to avoid contamination by the oils in the human hand);

- kyōji [香筋] (ebony chopsticks used to move one piece of kyara from the kōgō onto the gin-yō, in the kōro);

- an object called an uguisu [鶯], or uguisu-kushi [鶯串] (a flat platform, often shaped like a plum blossom, through which a long toothpick-shaped needle is poked: the uguisu is used to create a flat top to the mound of ash in the kōro where the gin-yō will rest; and, simultaneously, a chimney through which the heat from the charcoal rises upward: the name comes from the fact that the uguisu [鶯] feeds on the pollen of the plum blossom, hence the platform is shaped like a plum blossom, while the needle poking through suggests the bird's beak penetrating deep into the flower);

- koji [火筋] (metal chopsticks used to handle the burning tadon [炭團] -- the little briquettes made of processed charcoal that were used to heat the kōro);

- hai-oshi [灰押] (an object, shaped like a closed folding-fan, that is used to press the ash in the kōro into a conical shape after the burning charcoal has been put inside);

- and a miniature habōki [羽箒] (a feather duster used to clean the rim of the kōro after the ashes have been shaped).

¹⁸Kōro Usu-gumo [香爐 薄雲].

Usu-gumo [薄雲] is the name of a famous variety of kyara incense wood (not a kōro). Tanaka Senshō's manuscript (which was the document copied by Jitsuzan with the Shū-un-an papers before him) reads kō-bon ni kōro ・ usu-gumo mei-kō ・ kōgō futae aogai [香盆ニ香爐 ・ 薄雲 名香 ・ 香合 二重青貝], suggesting that Tachibana Jitsuzan made a mistake when transferring this information from his original notes to the notebook that he intended to present to the Enkaku-ji*.

As for the kōro itself, since Rikyū does not give a name, it was probably not the celadon Chidori kōro [千鳥香爐] that had been one of Jōō's treasures. Most likely, it was the ido-kōro [井戸香爐], that is shown below.

This kōro is now known as Kono-yo [此世], the name he wrote on its box (and presumably gave to it) just before his death.

__________

*While Shibayama Fugen states that Usu-gumo [薄雲] is the name of the kōro, it must be remembered that Fugen was relying on a set of notes set down by one of the auditors during the discussion of the Enkaku-ji manuscript that took place after Tachibana Jitsuzan had presented his text to that temple. In order to preserve the secrecy of the text, it appears that it was forbidden for the participants to write anything down while they were in the Enkaku-ji. Thus, this document was set down only after the person had returned to his home. (As such, it is rather remarkable that, on the whole, the text is exactly the same as the Enkaku-ji version. Copies taken from this manuscript circulated around Kyōto for many years, until the authentic Enkaku-ji version was finally published in the middle of the 20th century, and I have had the chance to inspected several of these copies on different occasions.)

¹⁹Kōgō futae ao-gai [香合 二重青貝].

Ao-gai [青貝]* is mother-of-pearl inlay.

Most surviving ao-gai kōgō from Rikyū's period are of the usual sort. A much smaller number have three levels (mie-kōgō [三重香合]). Kōgō with two levels (futae-kōgō [二重香合]) are all but unknown today, since they do not meet the modern demands as established by the tea schools†.

__________

*More commonly known as raden [螺鈿] today.

†A kōgō with two levels usually held the incense (enclosed within small envelopes) in the upper level, and a supply of gin-yō [銀葉] in the lower. Burned out incense pieces (which were fused to the gin-yō on which they were heated) were discarded into a separate taki-gara-ire [炷空入] -- often the kind of container used as a ceramic kōgō today.

A three-level kōgō includes a silver-, pewter-, or copper-lined lower level into which the burned-out incense is discarded.

It appears that Rikyū intended that the kōro be placed in the toko after the guests had finished appreciating the incense, so that it would continue to perfume the room during the remainder of the chakai. In fact, it may have been to suggest this intention that he did not arrange a taki-gara-ire on the kō-bon -- as would have been customary.

²⁰Kyōji-tate [キヤウシ立].

This is a vase-like object, usually made of metal, in which the implements used when preparing the kōro* are kept when not in use.

___________

*See footnote 17 for a complete listing of these things, including a description of their purposes. Rikyū probably abbreviated the number of things, since some of their functions could be performed by the utensils used during the sumi-temae (the regular ro-yō hibashi, for example, would have been used to transfer the burning tadon from the ro to the kōro; and the large habōki to dust the rim of the kōro).

²¹Habōki [羽帚].

This was an ordinary habōki, made from feathers around 1-shaku in length.

While it is not possible to know what kind of feathers were used, it was the season when the geese were flying north, and so these birds would have been taken from time to time by Hideyoshi's hawkers, with the feathers available to Rikyū for his purposes.

²²Kōro mawarite issumi ari [香爐マハリテ一炭アリ].

In other words, the tadon [炭團] (a small briquette of high-quality processed charcoal that is used to heat the kōro) were placed in the ro just before the guests entered the room for the shoza*, so Rikyū began the gathering by inviting the guests to appreciate incense, then prepared the kōro and offered it to them.

After they were finished, the kōro was placed in the tokonoma (probably by Rikyū)†, and Rikyū turned his attention to the ro. Because, according to san-tan san-ro [三炭三爐] practice, the fire in the ro should be rebuilt at midday (after having been laid at dawn), the charcoal would have burned down to mostly hot embers by this time‡, thus Rikyū would have added a more or less full set of charcoal, as he notes (rather than the several pieces added during the sumi-temae at a morning or evening gathering**). His use of the term issumi [一炭] implies that Rikyū had not replenished the fire prior to the arrival of his guests.

__________

*The use of the small tsuri-gama would have helped facilitate the insertion and removal of the tadon without having to take the kama out of the ro first.

When a large ro-gama was used, Jōō said that the gotoku should be moved diagonally toward the far left corner when the ro was set up, thus leaving more space in the front right corner for the host to reach in (with the ro-yō hibashi) to remove the tadon. (The koji [火筋] would never have been long enough to reach the tadon kindling deep in the ro.)

†The piece of kyara would not have been anywhere near exhausted by the time that the two guests finished passing it back and forth three times -- one piece of kyara (about 5-bu square) was intended to last long enough for five or six (or even up to ten) people to appreciate it three times each before its fragrance began to disappear. Therefore, to remove the kōro from the room would have been wasteful. The fact that Rikyū did not prepare a taki-gara-ire [炷空入] suggests that the idea of placing the kōro in the toko was planned beforehand (and the kane-wari for the goza also bears this out -- since the kōro was left in the toko until the end of the chakai).

Rikyū would have gone out to the katte and brought a small tray of some sort into the room that would serve as a base for the kōro when it was lifted into the toko. It would have been placed between the bon-san and the toko-bashira, forward of the midline of the toko, and associated with a yang-kane, as shown in the sketch.

‡Dawn occurs around 5:08 on April 10 in this part of Japan. Thus, the fire in the ro would have been burning for at least seven hours when this chakai began. The charcoal would have been reduced to ash-covered mounds (referred to as shira-zumi [白炭] by Jōō in the Hundred Poems), with perhaps only the large dō-sumi [胴炭] still partially intact. The dō-sumi would have been broken in half with the hibashi and moved to the middle of the ro, with the remaining embers (knocked free of their white ash coating) piled around it, after which shimeshi-bai would have been sprinkled over the white ash to make the ro look tidy. Then the wa-dō would have been placed on the right side of the pile of embers, toward the right-front corner of the ro, and then gitchō and wari-gitchō were added in a circle around the embers. This was how Rikyū arranged the charcoal.

During the ro season, the white eda-zumi [枝炭] -- carbonized azalea twigs coated with gesso -- were not used by Rikyū. These were used only during the furo season (if they were used at all by him), when laying the fire around a shita-bi of three burning gitchō. It is completely wrong to call the eda-zumi “shira-zumi” [白炭], and this mistake has lead to much confusion over the meaning of several of Jōō's verses in the Hundred Poems.

**The fire was added to the ro at dawn, so by the time of a morning gathering, the fire would still be fairly strong, with much of the charcoal still unburnt.

Likewise, the ro was emptied, cleaned, and a new fire was laid at dusk. Thus, when an evening chakai was scheduled, the fire would still be fairly strong, necessitating the addition of only a little charcoal to bring the kama back to a boil and keep it boiling until the service of usucha was concluded.

In the case of this chakai, however, the fire in the ro when the guests entered would have been the one laid at dawn (and, since a morning chakai had not preceded this one, the charcoal would have mostly burned down by this time). Consequently, the sumi-temae started with the collection of the burning embers into the middle of the ro, followed by the addition of a wa-dō [輪胴] -- the large circular piece cut from the thickest end of the long piece of charcoal as received from the charcoal shop -- which had to be retrieved from the bottom of the sumi-tori (unlike now, Rikyū placed the large pieces on the bottom and then piled gitchō and wari-gitchō on top to fill the sumi-tori; meaning that a number of these smaller pieces had to be moved into the haiki before the large piece on the bottom could be accessed, and the rest of the sumi-temae took place using the smaller pieces from the haiki) as the foundation for the new fire. Then a number of gitchō and wari-gitchō were used to encircle the embers. The arrangement, therefore, was much simpler than what evolved during the Edo period; but the very lack of strict rules meant that it also required careful thought on the part of the host -- so that he would add enough charcoal, yet not too much.

The elaborate sets of charcoal of different sizes and shapes concocted by the various tea schools during the Edo period were intended to make the task of building the fire as easy as possible -- so that even an incompetent host (someone with no real interest in chanoyu, for example) could manage to get the kama boiling without too much difficulty. And the go-sumi-temae [後炭手前], performed between the koicha-temae and the usucha-temae, meant that he did not have to worry that the kama would stop boiling before the service of tea was finished.

²³Sakemono jū-jū [サケ物重〻].

Both Tanaka Senshō and Shibayama Fugen have Sagemono-jū ni [サゲ物重ニ = 提げ 物 重 ニ] for this entry. A sagemono-jū [提げ 物 重] -- or sage-jūbako [提げ重箱] -- is a set of multi-tiered food boxes that can be carried by hand (such as to a picnic -- the purpose for which such sets of boxes were originally created). The particle ni [ニ], of course, means “in.” That is, the kashi enumerated below were all arranged in a stacked set of boxes, from which the guests were free to help themselves.

²⁴Yomogi no mochi [ヨモキノモチ].

This was mochi (steamed rice-cake) made with yomogi [艾] (mugwort, Artemisia princeps), which makes the mochi dark green and gives it an herbal flavor and smell. Yomogi-mochi were traditionally served on the Third Day of the Third Month.

In the old days, large sheets or cakes of mochi made with yomogi were cut into small pieces and simply served in that way. By the Edo period, mochi dough was wrapped around a ball of sweetened anko [餡子] made from the red azuki [小豆] bean. It is not known which sort of yomogi-mochi Rikyū offered to his guests during this chakai.

²⁵Nimono tori ・ kushi-awabi ・ shiitake ・ mame ・ musubi-me [煮物 鳥 ・ 串アハヒ ・ 椎茸 ・ マメ ・ ムスヒメ].

These “kashi” were all cooked by boiling in broth (nimono [煮物]). However, they would have been drained (and probably allowed to cool off) before being put into the box. These offerings consisted of:

- tori [鳥]: probably small birds (such as sparrows or finches), mashed into a paste and formed into dango [團子] (meatballs) that were threaded on a skewers in threes and so boiled;

- kushi-awabi [串鮑]: abalone that had been dried on skewers, rehydrated by boiling in broth, and then sliced;

- shiitake [椎茸]: probably dried shiitake mushrooms that were boiled in the broth after having been soaked in water overnight (the drying process makes them sweeter and more flavorful, and so better for boiling than the fresh mushrooms);

- mame [豆]: probably the large, white ōfuku-mame [大福豆], an especially large variety of the common ingen-mame [隠元豆] type of beans;

- musubi-me [結び芽]: wakame [ワカメ = 若芽] (a type of green seaweed, Undaria pinnatifida, that resembles a small size kelp), cut into short lengths that were then tied into decorative knots.

²⁶Mizu-kuri [水栗].

Raw chestnuts that have had part of the brown pellicle carved away with a knife, then soaked in water for several hours to remove the bitterness from the remaining pellicle before serving.

According to Tanaka Sensho, the pellicle was scratched away from half of the chestnut in a coma shape, resulting in a three dimensional futatsu-tomoe [二つ巴] design (the “yin-yang symbol”).

²⁷Go [後].

The go-za.

In terms of kane-wari:

- the toko, which now contains the scroll, the bon-san, and the kōro, would be han [半];

- the room remained han [半], since all it contained was the kama in the ro;

- and the daisu was also han [半]*.

Han + han + han is han. This is correct for the goza of a chakai held during the daytime.

___________

*The ji-ita remained han, and the ten-ita, with the sasa-mimi and a naka-bon bearing the kasane-chawan and a natsume, would have been chō. Han + chō is han.

²⁸Chaire sasa-mimi [茶入 サヽ耳].

The sasa-mimi [笹耳]* is a rather exaggeratedly etiolated chaire, originally made as a vessel for perfumed beauty-oil (the shape allowed it to be poured out without splashing); the pair of ears were there so that a cord could be tied onto one, crossed over several times as it passed over the stopper, and then tied onto the other ear to secure the lid and prevent spillage. Chinese sasa-mimi containers came in several different colors, with brown (as seen below) and egg-shell-white being most common.

Rikyū has marked this chaire with a red dot, indicating that it was one of the featured utensils -- probably as a nod to the fact that it was the Hina-matsuri.

Though described first, the tea in the sasa-mimi was used to serve usucha. Therefore, though the sasa-mimi was usually provided with a shifuku, the shifuku was removed and placed flat on the daisu on this occasion (to protect the lacquer of the ten-ita from being scratched by the foot of the chaire) with the sasa-mimi standing on top of it.

___________

*Sasa-mimi [笹耳] means “ears shaped like the leaves of the bamboo-grass.”

²⁹Naka-bon ni [中盆ニ].

This could have been either be a square tray or a round one.

³⁰Natsume ・ kasane-chawan ・ ori-tame [ナツメ ・ カサネ茶碗 ・ 折タメ].

The natsume (probably a ko-natsume [小棗], since there were only two guests) contained tea for the koicha*.

It is not possible to guess which chawan Rikyū used on this occasion†, though the chakin, chasen, and chashaku (shown below) would have been arranged in the upper of the two bowls.

The chashaku was one of Rikyū’s ori-tame, and example being shown below.

As for how the chashaku may have been displayed, there are two possibilities:

1) it may have been placed across the rim of the smaller chawan, as shown in the left sketch;

2) or, it may have been placed on the tray, with the handle resting on the front rim, between the kasane-chawan and the natsume, as shown on the right‡.

___________

*The tea in the container displayed on the tray was considered to rank above that in the container that was not placed on a tray.

†The word kasane-chawan [カサネ茶碗] appears several times in the Nampō Roku, but the particular chawan used by Rikyū for this purpose, or their sizes, are not discussed.

Somewhat later he used a pair of black Raku-chawan (known as o-guro [オグロ, 小黒], “small black,” and ō-guro [オーグロ, 大黒], “large black” – the smaller bowl, which still exists, is around 3-sun 8-bu in diameter; while the larger, which has disappeared, was a little over 4-sun in diameter) as his kasane-chawan; but at the time of this chakai Chōjirō does not seem to have started producing his black bowls yet. (They first appeared during the summer -- according to a questionable entry in this kaiki -- or early autumn of 1587, perhaps making a sort of debut to the tea world at the Kitano ō-cha-no-e [北野大茶會], which opened on the First Day of the Tenth Month of that year.) . As mentioned above, only the smaller bowl survives now, and somehow it has acquired the name of the larger of the pair.

In the sketch I suggested one of the ido bowls as the larger chawan, with an aka-chawan as the smaller, but this is pure speculation.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

#ken renders#ken renders hina tachibana#tokyo revengers#tokyo revengers hina#tokyo revengers hina tachibana#hina tachibana#hina tachibana render#tokyo revengers render#tokyo卍revengers#tachibana hina#tachibana hina render#female anime render#東京卍リベンジャーズ#image anime render

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#ken renders#ken renders hina tachibana#tokyo revengers#tokyo revengers render#hina tachibana#hina tachibana render#tachibana hina#tokyo revengers hina tachibana#tachibana hina render#female anime render#image anime render#東京卍リベンジャーズ#tokyo卍revengers

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#ken renders#ken renders hina tachibana#tokyo revengers#tokyo revengers hina#hina tachibana#hina tachibana render#tokyo revengers render#tachibana hina#tachibana hina render#female anime render#東京卍リベンジャーズ#tokyo卍revengers#image anime render

1 note

·

View note

Photo

#ken renders#ken renders hina tachibana#tokyo revengers#tokyo revengers render#tokyo revengers hina#tokyo revengers hina tachibana#hina tachibana#hina tachibana render#tachibana hina#tachibana hina render#東京卍リベンジャーズ#female anime render#tokyo卍revengers#image anime render

1 note

·

View note

Photo

#ken renders#ken renders hina tachibana#tokyo revengers#tokyo revengers hina#tokyo revengers takemichi#tokyo revengers hina tachibana#hina tachibana#hina tachibana render#takemichi x hinata#takemichi x hina#hina and takemichi#hina x takemichi#takemichi hanagaki#takemichi hanagaki render#tokyo卍revengers#東京卍リベンジャーズ#image anime render#couples anime render

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#ken renders#ken renders hina tachibana#tokyo revengers#tokyo revengers hina#tokyo revengers hina tachibana#hina tachibana#hina tachibana render#tokyo revengers naoto#tokyo revengers naoto tachibana#naoto tachibana#naoto tachibana render#naoto and hina#image anime render#東京卍リベンジャーズ#tokyo卍revengers

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#ken renders#ken renders hina tachibana#tokyo revengers#tokyo revengers takemichi#tokyo revengers takemichi x hina#takemichi x hinata#takemichi x hina#hina and takemichi#hina x takemichi#tokyo revengers hina#tokyo revengers render#hina tachibana#hina tachibana render#takemichi hanagaki#takemichi hanagaki render#takemitchy#tokyo revengers takemitchy#東京卍リベンジャーズ#tokyo卍revengers#couples anime render#tokyo revengers couple

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

happy new year 2022 to all the people who follow me

there have been a lot of interesting anime, some nice some very nice, but shadow house is the new anime I have preferred,I hope that in this new year new beautiful souls come out, always waiting for new hibike content I cross my fingers XD

#ken renders happy new year 2022#happy new year 2022#happy new year 2022 anime#2022 anime#watamote#shadow house#domestic girlfriend#shinigami bocchan to kuro maid#kuroki tomoko#tomoko kuroki#emilico#emilyko#shadow house emilyko#shadow hosue emilico#watamote kuro#watamote kuroki#rui tachibana#hina tachibana#kuroki tomoko happy new year#emilyko happy new year#emilico happy new year#anime edits#chibi anime#kawaii anime girls#watashi ga motenai no wa dō kangaetemo omaera ga warui!

19 notes

·

View notes