#sweny dublin

Video

youtube

Ireland is a beautiful country

#ireland rocks mohair#dublin#beautiful ireland#ireland weather#dublin castle#sweny dublin#irish people

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Musicians are leading the public in a rendition of Fairytale Of New York outside Sweny’s pharmacy in central Dublin. A large crowd has turned out for the funeral procession of Shane MacGowan before his funeral in Co Tipperary.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Glass Trunk, Richard Dawson (2013)

In Dublin once, I popped in to visit Sweny’s Pharmacy, a bookshop (and once an actual pharmacy) made eternal by James Joyce, and, after a series of circumstances I cannot remember, found myself being serenaded with Gaelic folk by a very old and very charming shopkeeper-slash-owner. It was a delightful experience; in that earthy shop, surrounded by historic nick-nacks and with the rain whistling outside, it felt appropriate, authentic. I appreciated it a lot.

But in many ways that sort of performance is very experiential; it relies so much upon circumstance and the performer, in its place in my life between where I was and where I was going. It isn’t necessarily something I’d necessarily enjoy at any time, in any place. And that, in many ways, reflects how I feel about Richard Dawson’s The Glass Trunk.

Employing aspects of sweeping a cappella, jagged guitar, winding storytelling, liquid in form, I understand that Dawson wouldn’t be the artist he is today without these kind of works, those that lay bare his historicity, creative method and well-versed appreciation for folk’s antecedents. The Glass Trunk is vital for Dawson’s listeners in that it helps form a fuller portrait of him as an artist, of where he’s been and the influences behind future tunes. But for me it’s more document than something to cherish. It is a work I’m rarely in the mood to re-experience.

Pick: ‘A Parents Address to His Firstborn Son on the Day of His Birth’

0 notes

Text

The bananas have ripened, which means I must eat all of them quickly. I should have put two in the fridge to stagger them. This is my first one in a long time, so it is especially delicious. I toast and butter two slices of sourdough and smash the banana into it’s sturdy fabric. Then, I reach for the fancy ginger shaved chocolate my mother has sent me to sprinkle on the top like the Dutch do. It’s intended as a drink, but this is the best way to have it.

It’s Sunday and the clocks have gone back, so only the dog walkers are out at 8. Dogs have their own uses for clock time, Pavlov’s creatures do not need to hear a bell, but they don’t know about this custom, so for her it is 9, and I have been lucky she has allowed me to postpone the outing for so long.

In the count down to the trip I have spent time looking at raincoats online. I actually own a long parka though, and although it’s not my favourite coat I might be best off accepting my irritation and taking it anyway. Better the devil you know. If it’s rainy in Ireland it’ll protect me, though the hood is very wide and blows back if caught in the wind.

Annette had told me about Sweny’s Pharmacy, the tiny museum to James Joyce, some time ago, and although I love him and have downloaded both Ulysses and Dubliners to relisten to on the trip I don’t feel an urgency to see it.

Andrew Scott reads Dubliners, he’s always a treat. I watch a series on Netflix about some young women muddling through their lives in Dublin. It looks like London, Georgian and Victorian bones swamped by glass and steel and I glumly wonder if I might just spend the week swimming in the hotel pool and hanging out in the room.

Then suddenly Belette shares something on Facebook about how Francis Bacon’s studio was taken apart in London and reconstructed in Dublin. Now, this I will make it my business to see. I don’t know why I had no idea that this reconstruction had happened, but there we have it.

There’s a particular famous photograph of the studio, showing the silted mess he worked in, taken from the doorway, with with a large, round, partially desilvered mirror in the centre, reflecting nothing, staring blankly back at the room. The conservators must have worked like archaeologists, so layered and complex was their task. Belette notes that they were careful to preserve not only the objects themselves but also the specific layer of dust each object had accrued.

I realise that I’ve been writing about autumn and comfort food and rain and care as though my thoughts themselves are cosy. They are not. On my dog walk I have been thinking about rage and disgust. It is as though there is a balance to be made and the more instability I feel inside the more stable I must make the conditions around me. I photograph a huge mushroom in the park which has grown massive since I photographed it a few days ago, when it was young and tall, only undisturbed because the area is fenced off. Growth itself is delicate. There are times when interruption is disruption. What a fragile and violent place is this earth.

#bananas#daylight savings#Ireland#Dublin#james joyce#ulysses#actually adhd#actuallyautistic#original writing#dubliners#francis bacon

1 note

·

View note

Link

“All of us become pilgrims at one time or another, even though we may not give ourselves the name.” –Richard Niebuhr

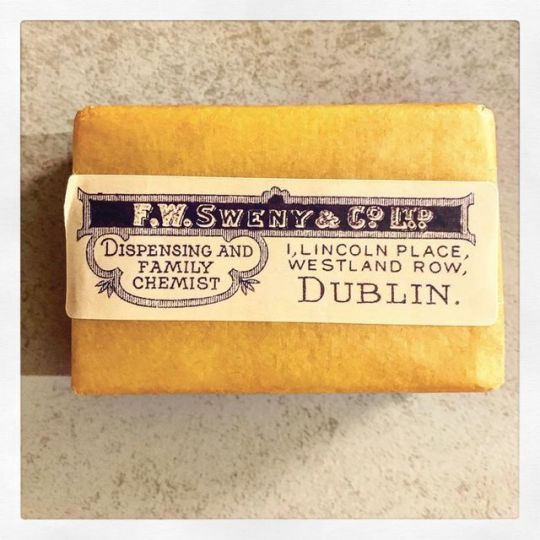

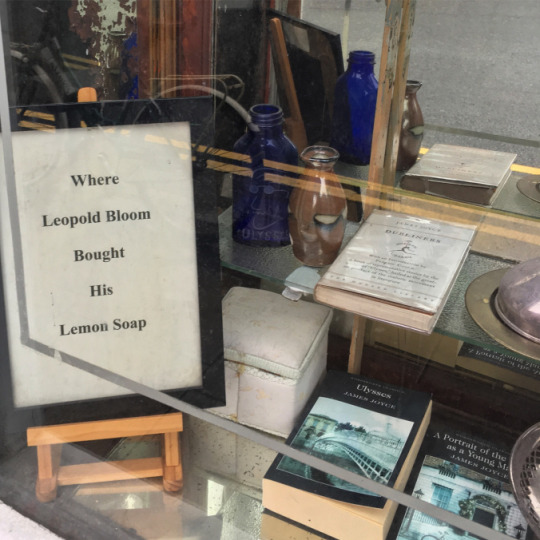

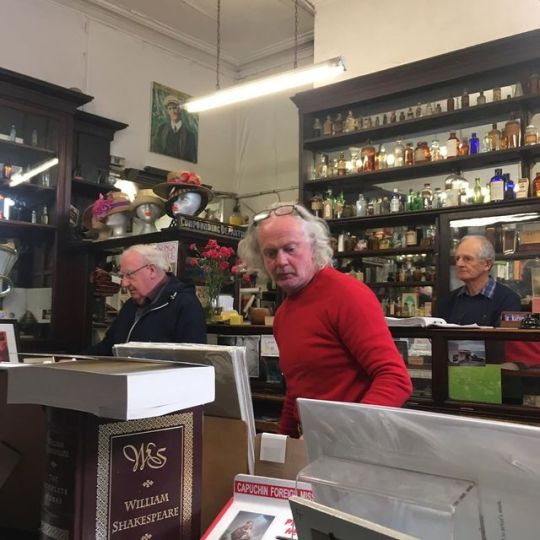

PJ, who presides over Dublin’s dusty shop Sweny’s, has read Joyce’s Ulysses 51 times in 6 different languages. Over a dark pint of Guinness, with the mist from the glass melting on his fingertips, PJ speaks about the lines from the book that are making his pulse race that minute. He doesn’t try to persuade you of their sacredness or its genius. He just smiles slightly, revealing coffee-stained and wayward teeth, and nods as he cites whole paragraphs. PJ loves Joyce. To PJ, Sweny’s, the shop where Leopold Bloom bought lemon soap for his wife Molly in Joyce’s epic, is an invaluable relic of Joyce’s Dublin, and he would do anything to protect its legacy. Even as rent steadily increases, PJ continues to sell bars of lemon soap in the chemist’s shop, now cluttered with old photographs, various editions of Ulysses, and hundreds of small glass bottles. PJ says with a wry smile, “the soap cleans the body while the book corrupts the mind.”

Every year on June 16, the same date that marked Leopold Bloom’s walk around Dublin in 1904, a host of literary pilgrims visit the city to pay tribute to Joyce. Sweny’s was a sacred stop on the tour for people I met last Bloomsday, people who came from Australia, Japan, Bosnia, South Korea, the United States, Germany, Spain, Argentina, England, France, and Switzerland.

In the Catholic tradition of pilgrimage, a location that is considered sacred is often referred to as a “thin place,” a place where the space between heaven and earth wanes, and becomes rarefied or thin. Such places typically mark the site of a saint’s ascension, a miraculous act, or some epiphanic moment. In other religions, places may be considered sacred because they have been saturated with meaning by God. What might a thin place be in a conversation about literary pilgrimage? Perhaps where the distance between an author’s imagination and a reader’s lived reality narrows and eventually collapses. And where the human being who generated meaning in the place—the author, the artist, the genius—begins to acquire divine status. Joyce certainly seems to assume deific qualities every year on Bloomsday as devotees travel to Dublin and re-enact the events from Bloom’s life, visit the places he walked, and read excerpts of Ulysses aloud.

In the home I grew up in, we consider all books sacred, and one of my family’s South Indian traditions has become practically reflexive for me. When someone accidentally drops a book or grazes one with a foot, we place our hand on the cover and gently touch our closed eyelids. We thus symbolically ask forgiveness for treating a book with inadvertent disregard. My parents instilled in me a deep appreciation for written words. Literary pilgrimage provides an opportunity to reflect on that appreciation, and on what happens when it extends beyond an individual gesture to a collective expression of reverence. Why do people become dedicated to one author, or one text? And how does that dedication evolve from fleeting infatuation to persistent devotion?

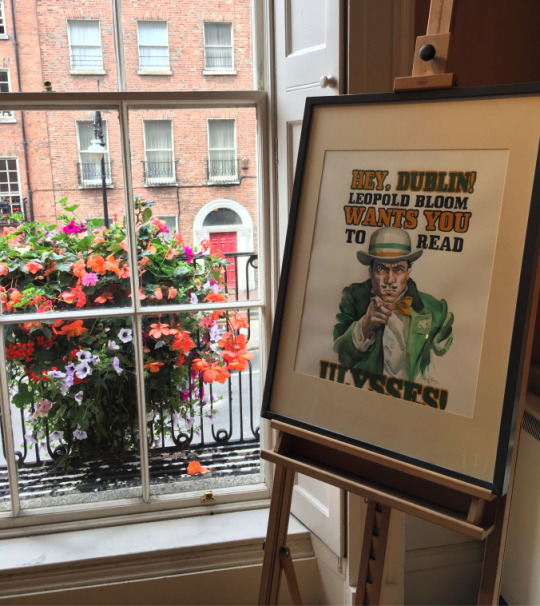

Last summer, on a quest to reckon with these questions, I attended the Bloomsday festival, which is primarily organized by the James Joyce Center on Dublin’s North Great George’s Street. Deirdre Ellis-King, the chair of the board of the James Joyce Center, notes that the center is committed to providing “different points of entry” into the text, be it “music and song, drama, costume, or food.” The entry points Ellis-King referred to are visible throughout Dublin on Bloomsday. As I walked down North Great George’s Street, people were dressed for the trends of 1904—most men sported black top hats, and carried walking sticks, while women donned petticoats, lace gloves, and parasols. One man even tipped his hat, saluted me, and said with a melancholic tinge, “what a shame, poor fellow, Paddy Dignam,” referencing the character whose funeral in Ulysses occurs on June 16.

When I arrived at Davy Byrne’s, a central pub in the novel, I witnessed a joyful uproar of Irish anthems and songs from the book. There were productions of Ulysses all over Dublin, from the Abbey’s adaptation of the entire epic to the Bewley Café’s staged reading of Molly Bloom’s monologue, and her famed finale, “and his heart was going like mad and yes I said yes I will Yes.” There were pub crawls across Dublin, not to mention food tours that took visitors down Bloom’s bizarre trajectory of consumption, from kidneys for breakfast to gorgonzola sandwiches and burgundy for lunch. All these events were meant to challenge the notion that Ulysses ought to be abstruse and abstract for readers. Bloomsday participants come with varying levels of Ulysses knowledge, but even if you haven’t read the book, you can still down a pint or digest a kidney.

Sam Slote, a professor at Trinity College Dublin, who has organized an academic symposium on Ulysses, cites Joyce’s remark, “If I can get to the heart of Dublin, I can get to the heart of all the cities of the world.” Slote comments that in order “to get to the heart of Dublin, Joyce represents the city in all its specificities.” In this way, he “gets to everywhere else and all their specificities.” Deirdre Ellis-King agrees, remarking that “Joyce and Dublin are synonymous, it’s any-man and every-man, you could be in any city in the world and enjoy the same kind of experiences of the streetscape.” Paradoxically, by being so precise, the text becomes universal. This stylistic technique is analogous to the character of Bloom. “It’s not that every man likes kidneys for breakfast, but every man has his particularities,” Slote says. It is in this way that Ulysses speaks to any reader, any person in motion, any pilgrim—not in the specifics of every human being, but in the specificity with which any human being can be represented. No one is special. Everyone is special. Stephen Dedalus, the other main character in the novel, has a line, “every life is many days, day after day.” This could be the motto for not only the epic, but also the festival commemorating June 16—any day, in any life, could be Bloomsday. The annual convergence of time and place restores significance to every ordinary and individual encounter, to every overlooked dollop of time.

Jessica Yates, who oversees the Bloomsday festival and manages the James Joyce Center, tells me she “converted” to Joyce (her word) because of Bloomsday. Unlike people who embark on a pilgrimage to honor the text they love, Yates casually went out to a pub on Bloomsday eleven years ago without any prior knowledge of Ulysses. It was there that she met “someone special,” and they set out on a project to read Ulysses before their first anniversary. She says with a trill of laughter, “I got so into Bloomsday.”

She recommends I sit in on one of the storied reading circles at Sweny’s. I do, and am struck by the variety of voices present. Some readers sit with a cane or walker leaning against theirs chairs, and others sprint over to the shop after class. As Joycean phrases echo in the small confines of Sweny’s, I hear accents from Argentina, South Korea, and France. One Dubliner named Paddy has been attending the reading circle on and off for about a decade. Paddy wears long trousers, a light blue button down shirt, and round reading glasses. He seems serious, but he also has a toothy grin. While some wanderers came into the bookshop after one or two beers, Paddy arrives early, eager to pour over the text he deems so valuable. He has read the book in 6-month cycles about ten or eleven times—he can’t recall exactly. He views Ulysses as a vessel through which he can access his own ancestors, a thin place with miraculous possibility. He explains, “I am from Dublin. My parents, my grandparents too. I have no non-Irish connections. I think I am deeply of Dublin, and there are few books deeply of Dublin. Ulysses is one of them.” He explains why the book resonates with him emotionally by pointing to its melodic qualities: “There is a music in the language, a rhythm in the speech. I can hear my parents who are now dead, my grandparents who are now dead, I can hear them talking, when I read it, I can hear their voices.”

Yet another regular at Sweny’s is Finon, a former student at Trinity College. He has been attending readings of Ulysses for four years, and he loves how Sweny’s regulars move “in a loop,” how the book itself is like a “carousel, no fun unless you get to do the whole thing.” “After all,” he chuckles, “if you haven’t finished, it’s not worth the money.” Like many sacred texts, Ulysses contains philosophical reflections, surprising imagery, and beautiful poetry. And like many religious holidays, which draw pilgrims from all over the world to a holy site, Bloomsday too, according to Finon, becomes a “spawning day,” to which “a lot of people return.” Both re-reading and pilgrimage are rituals of returning.

Attempts to disavow the sacred aspects of the festival sometimes sound inadvertently religious. When Finon describes the goal of Bloomsday, he seems a bit like a defensive missionary: “The attempt to popularize the text is really an attempt to create an invitation into it. I mean nobody’s looking to actively spread it onto people, but to keep it as welcoming as possible.” Similarly, Jessica Yates says she wants to get people excited about the text, but she insists, “I don’t want to impose it on everyone.” They are enthusiasts who hesitate to proselytize.

Indeed, Professor Slote of Trinity College Dublin notes with a hint of smug amusement that many people were asking him what he thought of Bloomsday from a scholarly perspective and he was “about to say something,” until he realized, “I’m not going to be this guy.” It would be understandable, from an academic standpoint, to scoff at some of what unfolds. For starters, many of the most devoted participants have never read the book. Take John, the James Joyce lookalike who has stood outside the James Joyce Center every June 16 for the last seven years. He carries a cane, and wears a black top hat, a suit, a healthy gray moustache and a tiny square beard. He peers through large circular spectacles, and takes photographs with tourists. Originally a hat-maker, John grew up in Dublin. He explains the mass of people at the James Joyce Center in an assured tone: “People don’t have to be readers to enjoy Bloomsday, people just like the association.” When I asked John what he thought when he read Ulysses for the first time, his eyes stretched open, and he raised his brows: “Read it? I wrote it!” I smiled, and he conceded, “I’m afraid I didn’t read it.”

For Joyce, a writer who said that if “Ulysses isn’t worth reading, then life isn’t worth living,” John’s confession could be considered blasphemous. But returning to Professor Slote’s less judgmental perspective, it’s unnecessary to “be that guy” who reads and analyzes Ulysses in order to have a genuine relationship with the text. Slote analogizes criticism of Bloomsday to what “we have in America—the [rhetoric of the] war against Christmas … the secularization of Bloomsday is not a bad thing.”

Is Bloomsday a sign that the religion of Joyce is somehow being compromised, challenged, thinned out in the public’s touristic, commercial and dangerously superficial imagination? Or is Bloomsday’s existence reaffirming the sacredness of Ulysses to its readers? After all, not everyone who travels to Lourdes has read the Bible, and not everyone who journeys to Mecca has read the Qur’an. The mastery of a text is not necessary, or at the very least, not a prerequisite for meaningful motivations. Pilgrimage provides a different kind of proof of faith.

As Slote elaborates on not wanting to be the Grinch of Bloomsday, he says, Bloomsday “is not a bad thing—usually it falls on nice, sunny weather,” and it’s “a pleasant excuse to have a bit of a lark.” He concurs with the organizers of the Bloomsday festival that it’s good to get people interested, and even though he says “my job is generally not to think about popularizing Ulysses,” he believes offering various points of entry for readers is noble. He elaborates on Joyce’s mission with Ulysses: “While it is a book that is studied at universities, it’s not just for those people. It has a wider audience. The way culture has moved, these things tend to be more academicized, [and] something like [Bloomsday] is a good counterbalance.”

Leslie Daugherty, from the North Side of Dublin, plays Leopold Bloom in the James Joyce Center productions of Ulysses, and he agrees that the so-called “secularization” of Joyce is a good thing. He describes the text as “a fabulous read,” but takes issue with some of the academics who treat Ulysses with the wrong kind of “reverence,” effectively “making Ulysses unattainable.” He objects to the notion that Ulysses is for “the posh people,” and shook his head as he said, in a throaty voice, “No. Ulysses is for everyone who has a mind of his own.”

Marty, a man from Donegal, Ireland, who is a marketing and events coordinator at the James Joyce Center, first encountered Joyce when he read A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, and he says with a chuckle that “a lot of teenage Catholic dudes in Ireland identified with it.” He describes being deeply moved by the part where Stephen is called to the priesthood but says, instead, that he is an artist. The tensions between religious tradition, devotion, expectation, and the inclination towards the life of an artist resonate with Marty.

Leopold Bloom, Ulysses, and Bloomsday itself are all fraught with similar tensions. Bloom is a man who loves his wife and preaches love but deceives her and behaves disloyally. Ulysses contains styles that contradict and challenge one another—clean prose, experimental stream-of-consciousness, advertisement jargon, and saccharine romantic-novel satire. Bloomsday has attendees who have read the text 51 times and people who have never heard of Joyce. The idea of “literary pilgrimage,” too, brims with ambiguity. Are books meant to be read, or to be revered? And does a book find its meaning in an isolated experience, or in a collective celebration?

In 1996, Jonathan Franzen revised an essay initially published as “The Harper’s Essay” and retitled it “Why Bother.” In it, Franzen laments the demise of a reading-culture, and describes his “despair about the American novel.” He writes about one novel he read in reverent prose, marking his gratitude “that someone besides me had suffered from these ambiguities and had seen light on their far side—that Fox’s book had been published and preserved; that I could find company and consolation and hope in an object pulled almost at random from a bookshelf—felt akin to an instance of religious grace.” The experience of literature, of reading as an act of worship, is often seen as an individual one, as it is in this passage. Indeed, the collection for which Franzen revised his essay is called How to be Alone.

Yet Bloomsday’s beauty is in its social activity. As many literary pilgrims have pointed out, Joyce wanted his text to be democratic. The point of Bloomsday is for “any man and every man,” and the text is about bringing reverence to our everyday. Ulysses itself, in various bodily and granular descriptions elevates the profane to an esteemed status. For example, in one instance, Joyce satirically describes a man seated at the foot of a large tower as a “broad-shouldered, deep-chested, strong-limbed, frank-eyed, red-haired, freely-freckled, shaggy-bearded, wide-mouthed, large-nosed, long-headed, deep-voiced, bare-kneed, brawny-handed, hair-legged, ruddy-faced, sinew-armed hero.” And just as Joyce plays with his characters, gifting them gallant qualities (albeit in a sardonic tone), so does Bloomsday toy with its visitors and their expectations, until people find communion in a collective, at times gimmicky, at times reverent experience. Ulysses motivates its readers enough that they want to change their physical circumstances, embark on an embodied passage, and develop another vantage-point—beyond the systems of logic and reason that we so often subscribe to. The book inspires people to find one another, to derive solace and soul, from an admittedly kooky community. This somewhat paradoxical combination of the sacred and the irreverent is what permeates Dublin on Bloomsday. There are pub crawls and exclamations of Joycean passages made shriller by grand glasses of Guinness. But there is also something reminiscent of what we see in churches and memorials—pilgrims, persons in motion—seeking answers, inspired by something that has no neat ending, maybe realizing as they wander, that they too, will never be complete.

Despite all the ambiguity and insecurity that is present when one sets out on a pilgrimage, there is also a yearning. People embark on a pilgrimage in search of something, be it healing, obligation, or understanding. And whether it is religious or literary pilgrimage, we can discover havens in vagrancy the way we do in words. As Franzen puts it, “to write sentences of such authenticity that refuge can be taken in them: Isn’t this enough? Isn’t it a lot?” There are not often clear answers in literature, but when paragraphs protect you, it doesn’t so much matter, does it? There are not clear lines drawn between the drawbacks and merits of Bloomsday either. Tourist Destination or Holy Site? One could easily say that the merits of Bloomsday are inits campiness, its accessibility, and its rendering a “thin place” palpable to readers. Franzen ends his essay with the image of a character discovering in a broken ink bottle “both perdition and salvation.” He writes, at peace without real resolution, “The world was ending then, it’s ending still, and I’m happy to belong to it again.”

Finon, one of the regular members of the Sweny’s reading circle, also embraces contradiction in Bloomsday. He believes that the festival is meaningful, but remarks with a knowing smirk that “on Bloomsday people like to drink and eat strange meat … [but] no one’s really talking about metempsychosis” (a concept of great significance in the novel). Finon asks if I had read Station Island by Seamus Heaney when I press him on the benefits and caveats of literary pilgrimage. I answer that I have not. He is keen to explain, “it’s a poem about revisiting a Catholic pilgrimage site, a catholic shrine …based on the idea that St. Patrick had a vision of purgatory there.” Finon outlines the context of the poem. “He was revisiting the place as a secularized figure … returning to a place he no longer believed in.” This raises an interesting question within a framework of literary pilgrimage. Is it possible to have a jarring return to a place you have lost faith in if all you have lost faith in is the sanctity of the literature (and not, for instance, the existence of God?)

In Heaney’s poem, various characters appear from disparate significant moments in the history of Ireland. And at the “dead center,” Finon narrates in a thrilled whisper, “he meets the ghost of the dead James Joyce.” Heaney doesn’t name him. He refers only to the storied image of Joyce that impersonators and photographers and readers and writers have memorialized for a century: a tall man with a cane, and the voice of a singer. Heaney writes that the figure held out his hand— “whether to guide or be guided I could not be certain,” because the man seemed blind. In this poem, an itinerant soul reckons with the loss of meaning in a formerly faithful location. That a hero of literature, a genius, artist, poet, is ambiguous in his leadership—that it is unclear whether he wants to lead or be led, demonstrates the deterioration and dismantling of Joyce as an idol, of Joyce as a God. Here Joyce’s hand is “fish-cold and bony,” and the onlooker knows him “in the flesh …wintered hard and sharp as a blackthorn bush.” This is a weathered, human being, a worn body, tired, old, nothing divine or eternal-seeming about him.

In many ways, this encounter could represent the ultimate challenge, a revisiting and reckoning with the sacred ground on which a metaphorical shrine to Ulysses was erected. In Station Island the character of Joyce does not seem wholly self-assured. He says, “your obligation / is not discharged by any common rite. / What you do you must do on your own … You’ve listened long enough. Now strike your note.” In this imagination of Joyce, the source of Ulysses’s genius, is not, on the surface, a divine force, because he feels entirely human. Yet, isn’t there something god-like in the command to strike out alone, to stop “listening,” and to embrace a new “rite”?

Considering Joyce as a simultaneously godly and ghostly figure is pertinent to the paradoxes of Bloomsday. Finon notes some logical dilemmas he observed on June 16 every year: “It’s a strange map in itself. I came to the real pub where a fictional character didn’t set foot. I came to the place where nobody bought the bar of soap. (laughs) It’s quite odd.”

Nonetheless, it seems hard to contend with the fact that Ulysses renders Dublin “a thin place.” It is the destination for wandering minds and bodies to relish and find refuge in words that feel mimetic of reality: the ugly, disturbing, devastating, and remedial stories that make up most of our lives. Letting Bloomsday be a thin place extracts communal joy from that solitary act of reading (or even of not-reading!) which can at times be isolating, and that private worship of Joyce, which can at times be embarrassing. A shared human soul pieced together from infinitely complex and individual particularities. One may plumb the mundane for miracles.

Niebuhr describes pilgrims as people “passing through territories not their own—seeking something we might call completion, or perhaps the word clarity will do as well.” I was passing through a territory not my own, and when I walked the streets of Dublin on Bloomsday, I felt both spiritual and giddy.

My very first interview, in the early morning of June 16, 2018, was with a couple from Trieste, and it felt like a moment of grace. I saw them loitering by the James Joyce Statue on the main street of the north side of Dublin. They were smiling and taking photos. It turned out that the man had read Ulysses as a young academic forty years ago. He matter-of-factly stated, “It was the text that inspired me to become a professor of literature.” As he spoke, his wife started laughing. I turned to her quizzically. She said, “Oh I’m sorry, it’s just my husband is really downplaying what this book means to him.” I asked her what she meant. “Well, when my first son was born—when I went into labor, what does my husband take along to the hospital? The thick fat book—Ulysses! He read it to me for twelve hours.” I turned to the man, now in his late 70s, a small smile playing on his lips, while a plum flush spread across his cheeks in patches. “Well,” he stuttered, “it’s sizzling…and brilliant…and so human.” This man wanted the very first words his son heard to be those of Joyce. What better anecdote could I have to demonstrate worship of this text? Yet, when I asked if he believed visiting Dublin for Bloomsday would lead to a more intimate understanding of Ulysses, he said, as his forehead creased slightly, “that would be too much, too big a claim.” His wife nodded knowingly. He added, “We’re here for more profane reasons.”

Literature enables both profane pleasure and reverence. On Bloomsday, no one has to choose.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Cheers PJ! @swenyspharmacydublin #swenyspharmacy @lovindublin #dublin @johnohare7 (at Sweny's Pharmacy) https://www.instagram.com/p/CJWuqFBH1e8/?igshid=mb095wwxcuyq

0 notes

Text

Jeudi 19 mars 19H-Cercle de Poésie - Paul Mathieu & Guy Denis

Jeudi 19 mars 19H-Cercle de Poésie – Paul Mathieu & Guy Denis

Suite aux succès des ateliers d’écriture avec Amandine Fairon, La Fée Verte vous propose une Soirée littéraire, lecture, poésie, débat, organisée et animée par Paul Mathieu et Guy Denis.

Venez (re)découvrir un 1/2 siècle de poésie, des vers d’hier et d’aujourd’hui, entre Ardenne et Gaume, retrouver l’esprit des cercles de lecture de la mythique Sweny’s Pharmacy, Lincoln Place, Dublinau coeur de la…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

#dublin #culturenight (at Sweny's Pharmacy) https://www.instagram.com/p/B2py-Tah41F/?igshid=3lna9sr2chzv

0 notes

Text

UP IN DUBLIN, LITERARY GHOSTS

UP IN DUBLIN, LITERARY GHOSTS

The door from 7 Ecceles street which Joyce made into a home for Leopold Bloom in his novel Ulysses

Haiku poetry based on Ulysses

James Joyce

Sweny Druggist in Dublin, featured in the novel Ulysses

Exterior of Blooms Hotel, Dublin

The Dublin Writers Museum

Beckett, Shaw, Wilde, Joyce, Behan, Yeats, Kavanagh, O’Brien…

Samuel Beckett

Bram Stoker

Oscar Wilde in Merrion Square

View On WordPress

#arts#Bram Stoker#Dublin#Dublin writers museum#History#Ireland#James Joyce#James Joyce Center#Leopold Bloom#Merrion Square#museum#National Library#Oscar Wilde#Samuel Beckett#Ulysses#WB Yeats#Writers

0 notes

Photo

#Sweny Dublin, Ireland 2017 ⠀ . . . . . #35mm #filmisnotdead #filmphotography #analog #london #stillifephotography #stillifelondon

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Saturday morning James #Joyce #Ulysses #reading group at Sweny’s Chemist #Dublin #Ireland where Leopold Bloom bought his #lemon #soap (at Sweny's Pharmacy) https://www.instagram.com/p/BxmeKq-HHfD/?igshid=1p76ejmczd5p0

0 notes

Text

Sweny’s Pharmacy

The former 19th-century pharmacy turned bookstore and craft shop was once visited by James Joyce and is even listed as a location in his world-famous novel, Ulysses. It was originally built in 1847 as a GP’s consulting room and became a pharmacy in 1853. It’s within 100 yards of the birthplace of Oscar Wilde and in 1904, the young James Joyce called to this very store. In Ulysses, Leopold Bloom, the fictional character, visits Sweny’s pharmacy to pick up a lotion for his wife, Molly. He consults with Frederick William Sweny the pharmacist at the time.

Stools are plotted around the room for visitors to sit, read and have a chat afterwards, creating a welcoming atmosphere.Unopened medicine bottles sit on shelves, ready to be curiously admired. A selection of second-hand books fill the space in the centre of the room, waiting to be browsed. Oh, and not to forget, there’s the lemon-scented soap on the counter, the very soap that made the shop famous!

Today it’s a must-see for any bibliophile on a trip to the Irish Capital.

Address: 1 Lincoln Pl, Dublin 2

Working Hours:

Tuesday 11a.m.–6:30p.m.

Wednesday 11a.m.–5p.m.

Thursday 11a.m.–6:30p.m.

Friday 11a.m.–6:30p.m.

Saturday 11a.m.–6:30p.m.

Sunday 11a.m.–6:30p.m.

Monday 11a.m.–5p.m.

0 notes

Photo

Day 4 was full of free time, which we used to wander and find interesting scavenger hunt items. The National Library, a statue in Temple Bar casually referred to as “The Tart with the Cart” (Molly Malone), and Sweny’s (a pharmicist in Ulysses that still exists today!). It was awesome to see the novel come to life right before my eyes. I wouldn’t trade this experience for anything.

0 notes

Video

#sweny #culturenight #dublin (at Sweny's Pharmacy) https://www.instagram.com/p/B2pvNGoAtio/?igshid=wjmm2eauuq82

0 notes