#selfobject

Text

The psychological paradoxes of Utsukushii Kare, part 1: Covert grandiosity and finding status through idealization

I’ve had some thoughts about Utsukushii Kare bouncing around in my head since the end of season 2. I started to post about them back then but my first attempts stalled out. Maybe the ideas involved were too complex, or I just needed to let them marinate a bit longer. I tried to give up on getting them on “paper,” but they just wouldn’t leave me alone. Eventually I returned to them and everything clicked. This is part one of my attempt to get those ideas down. After a ridiculous amount of tinkering, it seems like the right time to let it see the light of day. Subsequent posts are in different stages of readiness as well.

I wouldn’t have finished this without copious encouragement and feedback from @lurkingshan and specific edits from @wen-kexing-apologist. A kind comment from @nieves-de-sugui was a shot in the arm. And I’m always indebted to @porridgefeast for support, encouragement, and cute animal content.

I’ve written a lot about this series in the past; refer to my Utsukare master post for a continuously updated list. This includes some related posts on pursuer/distancer dynamics and attachment style in the series that have some overlap with what I’m discussing here, but this post should also stand on its own quite well.

A few things to note at the outset:

My focus here is on the series (both seasons), but I will refer to the movie, the novel, and a couple of vignettes when they illustrate points that are consistent with and relevant to the series.

My approach in this series of posts involves viewing fictional characters the way I would if they were real people--a bit like if I were to do a case conceptualization of a potential client. This isn’t always the approach I use, or the best one, but I thought it was a good fit for what I wanted to discuss here.

Quotes will be cited, but general information on sources will be given at the end of the post.

Now, to get down to business.

* * * * * * *

I’ve seen a lot of commentary from other Utsukare fans about Hira and Kiyoi and how much their self-worth–and the lack thereof–impacts their relationship. It’s a clear theme and lots of folks have had salient insights about it. But one thing I haven’t seen in any of the posts I’ve read is a full acknowledgement of the duality at play there–the way that both characters sometimes believe, or at least fear, that they’re irredeemably awful and at the same time believe, or perhaps hope, that they are better than everyone else.

I’m sure someone reading this is thinking, “Kiyoi is like that, sure. But Hira? Thinking he’s superior? Come on.” I get that it isn’t always apparent. In a genre that loves to portray profoundly smitten, devoted characters, Hira stands out as intensely, even excessively, whipped. But yes, Hira totally sees himself as superior to others in some important ways. Even before Noguchi Hiromi took his inventory about this so mercilessly, there were plenty of other signs.

covert grandiosity and idealization

Our introduction to Hira is his description of the “pyramid” social structure he experiences at school and how he’s at the lowest level of that pyramid (invisible at best, a visible target at worst). At first glance, this seems self-deprecating. But Hira is just describing where he falls in the structure, not endorsing the structure or his place in it. This sets up an important distinction that comes up continually in Hira’s thinking. Sometimes he really thinks badly of himself. But other times, he’s reporting how, in his view at least, others think of him. Sometimes he’s resigned to the ways others see him, but other times, he rebels against them. He doesn’t always make it clear which of these things he’s doing at a given time, but if you know what to look for it starts to be easier to pick out.

Mind you, it’s still very clear that there are ways in which Hira does view himself extremely negatively. His belief that he’s unworthy of Kiyoi is particularly strong. It inspires a lot of demeaning metaphors about himself, like calling himself a “pebble.” His belief in his unworthiness is linked to the belief that Kiyoi can’t possibly return his feelings or that if he does, it’s a bizarre miracle that can’t possibly last over the long term. The most remarkable thing about this belief is its incredible persistence, even in the face of example after example of evidence that Kiyoi loves and values him too and wants them to stay together. But denigrating himself in this context has a different meaning from what it would in others, as I'll get into in more detail shortly.

It’s a pretty universal human tendency to pay more attention to information that confirms our biases than information that challenges them. We’re also hard-wired to be more attentive to perceived threats (including threats to our sense of self-worth) than we are to less threatening things (and ideas). Both of these tendencies contribute to the fact that most of us fail to notice when our negative beliefs are being disproven.

I’ll be discussing this in more depth in part 2, but for now, I’ll just say that resistance to disproving a negative belief is very normal, but Hira’s stubbornness is way beyond what’s typical. He continually misinterprets or simply ignores clear signs of Kiyoi’s interest in and regard for him. I mean, most of us, no matter how poor our self-esteem is, no matter how jaded and pessimistic we are, would, if kissed by someone we’re in love with, at least entertain the possibility that they might like us a little bit. Not only does Hira not consider this possibility, he comes up with the rather bizarre interpretation that the graduation day kiss was Kiyoi’s way of telling him to leave him alone.

So, why would anyone be as stubbornly negative on this point as Hira is? Part of it is the strength of his negative beliefs and the degree of his bias. But there’s another reason as well, one I’m going to circle back to in a moment.

First, let’s look at Noguchi’s assessment of Hira in season 2, episode 4, which is very pertinent here. Talking about Hira’s submission to the Young Photographica contest, Noguchi says:

It was such a childish photo. You should've just chosen an empty place rather than erasing people. Going out of your way to [erase] people made it very clear that you hate this world. What I felt from your photo was tremendous selfishness and disgust. You haven't succeeded at all, but you think you're amazing. But instead of showing it outright, you make a shell by belittling yourself. You look down on this world with youth, stupidity, and ambiguity….You're just like the old me.

(dialogue from Viki subtitles)

It’s a little bit of a stretch, I think, to suggest that Noguchi can really tell all of this just by looking at a single photo (or even Hira’s entire portfolio). I think this partly happens just for the convenience of the story. But if I had to justify it, I’d say Noguchi has this much insight because, as he says, he used to be like Hira, making this a “takes one to know one” situation.

Hira confirms that Noguchi is correct here. “It’s like he sees right through me,” he thinks. So how do we reconcile this with Hira’s apparent negative self-image? Well, first off, it’s not unusual at all for very negative and excessively positive beliefs about the self to coexist in the same person. Take narcissism for example. People tend to think of narcissists as grandiose, thinking they’re amazing and special to a degree that’s clearly distorted. And that is one of the key symptoms of narcissism. But it’s also typical for narcissists to believe that if they aren’t remarkably special, they’re totally worthless. They have a hard time sitting with moderate (hence realistic) beliefs about themselves.

This kind of narcissistic tendency is really strong in people with Narcissistic Personality Disorder, but it’s present in a milder version in a lot of people (I suspect it’s present in most people, to some extent and under certain circumstances). Narcissistic personality traits are supposed to be linked to getting stuck at a developmental stage that ideally gets worked through during childhood. But a lot of us have at least a little bit of unfinished business from that period. I think Hira has a ton of unresolved stuff in this area. I definitely don’t think he would meet criteria for NPD. But I think that when he was in that developmental stage, he came up with some maladaptive strategies that helped him to get through it. As a result, he didn’t get stuck in the full-blown grandiose version of NPD, but he did get stuck with those maladaptive strategies, and they became a part of his personality instead. And he did retain 1) some of that highly polarized idea of self-worth (“I’m either the best ever or complete garbage”) and 2) some degree of belief in his superiority to others, no matter how shameful he finds it or how carefully he conceals it.

It’s also worth noting here that adolescents aren’t typically supposed to be diagnosed with personality disorders and even diagnosing young adults is often discouraged. This is because adolescence and early adulthood are times of intense change and development and the natural process of maturing can cause personality disorder symptoms to resolve even without mental health treatment. So that’s yet another reason to be wary of labeling Hira with any such diagnosis. This points to a major theme of the show, which is the fact that the central characters are works in progress. They aren’t fully formed adults yet, and that gives them a chance to improve themselves before they become set in their ways.

Getting back to Noguchi’s points: Hira is pretty misanthropic, although it’s often shown in pretty subtle ways in the show. This aspect of Hira is more noticeable in the novel. For one thing, the novel establishes early on that the erasing-people-from-photos thing isn’t some new or isolated phenomenon. Rather, the main thing Hira does with his camera at the beginning of the story is to intentionally take photos of populated areas and then carefully photoshopping out all of the people. And it’s explicitly because he dislikes, even hates, most of humanity. This tendency still comes through in the series. Sometimes it’s obvious–remember those mass shooting fantasies?--and other times, it’s more subtle. We know that this aspect of the character is definitely still present in the series version of Hira since he confirms what Noguchi says about how his photo shows “selfishness and disgust.” He really is disgusted by many of the people around him.

making a shell - perfectionism and covert grandiosity

What about the part of Noguchi’s spiel where he says that Hira “make[s] a shell by belittling [himself]?” It took me some thinking to realize what (in my view) he meant by that.

This actually syncs up really well with something Noguchi says about Hira in Utsukushii Kare: Eternal. It’s illuminating enough that I’m making an exception here to confining myself to the time period of the series.

In this scene, Kiyoi is scheduled to be photographed by Noguchi on a day that Hira isn’t present at his studio. He asks about Hira and he and Noguchi talk about him briefly. Hearing that Kiyoi was Hira’s high school classmate, Noguchi talks about how weird and confining high school is, a terrible “environment for growth.” He says that doesn’t apply to Hira, though, because he’s “a king in sheep’s clothing.” This catches Kiyoi’s attention. “I was just thinking that you understand him really well,” he tells Noguchi. “I do,” Noguchi replies. “Although he looks timid and weak, he’s actually really strong.”

As Noguchi continues, his comments become more metaphorical and get harder to understand. (I suspect that the metaphors he uses might be idiomatic or otherwise intelligible to a Japanese audience in a way that’s difficult to get across in translation.) The gist is that he sees Hira as “strong-minded,” but that “in his heart” he has a kind of “sanctuary” that he protects from others, and that this could end up either holding Hira back or being something he can use to get somewhere in life. I’m not sure what to make of the sanctuary part, but it’s clear that Noguchi understands that Hira has thoughts and emotions that he doesn’t share with anyone, and that his image as a “sheep” who is “timid and weak” masks an unseen strength and determination, along with a more king-like attitude toward the world than he typically shows to others.

Time for a quick psychological theory sidebar, this time on perfectionism.

Some researchers who study perfectionism have identified a type they call “narcissistic perfectionism.” Narcissistic perfectionists think that they are, or need to be, perfect, and they expect others to be the same way, thinking about them in highly negative ways if they don’t measure up. If you read about this idea, most of the examples given to illustrate it are people who have achieved a lot in their lives, who can point to big accomplishments. But perfectionism doesn’t always result in achievements. Sometimes it keeps people stuck in a mindset that anything but perfection is pointless, making them reluctant to really try to do anything at all. If you’re a perfectionist who has a need to believe you’re special, that you would achieve big things if you tried, actually trying means taking a risk that you’ll find out that when you try, the results aren’t actually perfect and amazing.

According to narcissistic thinking, this would mean that you’re worthless, because the options are either being the best or being complete garbage. Again, I think it’s an overstatement and an oversimplification to call Hira a narcissist, but he has unresolved self-worth baggage that takes a somewhat narcissistic shape. In this way, he shows a kind of perfectionism that seems clearly underpinned by his self-worth issues. Instead of fueling achievements, this perfectionism keeps him stuck, inactive, too afraid to attempt what he thinks he might be able to do while clinging to a fantasy of what he could do if he ever got un-stuck and really tried.

That’s usually a secret. Remember when Hira didn’t make it through the first cut of the contest? He thought, “Even though I always deny it out loud, I did think photography was the one thing I can do. It felt like I was being ripped apart for being conceited" (dialogue from a fansub by @lollipopsub). The fact that he would "deny it out loud" is notable. I also think that he’s still not being entirely candid. If he thought “photography was the one thing [he] can do,” that wouldn’t exactly be “conceited”--it would actually be quite modest (about photography) and harshly self-critical (about everything else). I think deep down he has thoughts that are truly conceited, thoughts that he’s not just competent when it comes to photography, but “amazing,” as Noguchi puts it. Once again, Hira confirms everything Noguchi said with his “he sees right through me” reaction, so he agrees with this assessment.

This conceited side of Hira is never supposed to see the light of day. This is the main reason he’s so intensely embarrassed when Noguchi understands him so well, I think. It’s what Noguchi is talking about when he says that Hira “make[s] a shell by belittling [him]self.” Acting as if he’s the lowest of the low is a defense. It does correspond to the part of himself that fears, at times even believes, that he’s worthless. But it’s also a way of hiding his grandiose side. This is a way of protecting himself from the reaction others would have if they could see how highly he thinks of himself despite not having made enough effort to accomplish the sorts of things he thinks he’s capable of. It’s also a way of protecting himself from his own awareness of his shortcomings and pretensions.

There’s another type of perfectionism researchers have identified, called “covert perfectionism,” in which the person’s outward expectations of others are low and they don’t show their perfectionistic traits outwardly very much, if at all. They’re supposed to be more likely than some types to get trapped in the kind of stuckness I mentioned earlier, in which perfectionism prevents the person from making a real effort at things they would like to do well. In some important ways, Hira’s perfectionism resembles this type as well. You could say that his type of perfectionism has definite narcissistic attributes, but he hides it well enough that it is also covert.

A number of different articles on perfectionism that I looked at cited the same Brene Brown quote about it, from her book The Gifts of Imperfection. I think it’s very salient here. She writes:

Perfectionism is a self-destructive and addictive belief system that fuels this primary thought: If I look perfect, and do everything perfectly, I can avoid or minimize the painful feelings of shame, judgment, and blame.

This is very characteristic of Hira. He doesn’t expect to “look perfect” in most respects (he’s more likely to simply try to go unnoticed). But he is obsessed with avoiding those painful emotions. He has spent his entire life being shamed and judged and living in fear of it happening still more. He’s very strategic and has given a lot of thought to how best to avoid being shamed. In fact, these efforts seem to be part of the reason he is such an avid observer of the social structures around him–learning about those structures is a survival skill for him.

idealization and affiliation: borrowing status

In addition to factoring in his covert grandiosity, I think there’s something else to account for when looking closely at Hira’s apparent self-hatred. Hira’s self-critical tendencies can appear inflated if we lump examples that pertain to his relationship with Kiyoi in with other cases. They should actually be looked at separately, because their meanings are distinctly different. Again, I don’t contest that Hira has a low opinion of himself in a lot of respects. But I think when we step back and look at many of the biggest examples of what appears to be a negative view of himself, a lot of them are focused on where he stands in relation to Kiyoi. That’s not the same thing as his value as a person. And placing himself in a certain role in relation to Kiyoi has a specific kind of meaning for him, along with a specific kind of payoff.

Here comes another theoretical interlude. This time, I’m going to briefly touch on Heinz Kohut’s idea of the need for idealization.

Kohut was the originator of a school of thought called self psychology, a branch of psychoanalysis that underpins a lot of contemporary psychoanalytic/psychodynamic theory and practice. He was also an expert on narcissism and basically saw variations and degrees of narcissism as central to a lot of psychological challenges. (There’s some reason to believe Kohut may himself have had narcissistic personality disorder, which would have made him intimately familiar with its inner workings.)

Kohut’s self psychology departed from Freud’s whole psychosexual development model (basically, everyone’s least favorite aspect of Freudianism—the part with all the penis envy and Oedipal stuff and so forth). In its place, self psychology focuses on how we see ourselves, what our needs are in terms of self-image, and other matters that are very relevant to this discussion. One of Kohut’s most important insights was his observation that even when other people have a big impact on our psychological state, what we’re interacting with isn’t so much the other person themselves but our internalized idea of that person. Kohut called internalized versions of people and things from our external world “selfobjects.” (I’ll be circling back to this momentarily.)

One of Kohut’s most central concepts is idealization. In Kohut’s version of idealization, a person views someone else as basically perfect, maybe even omnipotent. The idealized person becomes a special kind of selfobject. In the best case scenario, the person doing the idealizing has some kind of real, personal connection to the idealized person. But even a mental connection to them via their status as a selfobject can meet a need in some ways.

By feeling connected to, or even just affiliated with, the idealized person, the idealizer feels like they take on some degree of the qualities they see in the idealized person. It’s not hard to see how this tendency would date back to childhood. Children have a particular need to idealize their parents at certain stages in their development. Thinking of their parents as strong, capable, in control, wise, calm, etc. gives children a sense of safety and a sort of borrowed self-esteem.

Once you’ve idealized someone, you feel a real need to continue to see them as special and powerful. Again, childrens’ views of their parents are a good example here. One reason children often blame themselves when they are neglected or abused is because they have a strong need to continue to view their parents favorably. Without that favorable view of their parent, their world would seem chaotic and dangerous. Blaming themselves often seems safer. Here, maintaining the high status of the idealized person is so important that it’s a bigger priority than preserving self-worth.

I bet you can guess where I’m going with this. Yep, Hira idealizes Kiyoi in the Kohutian sense of the word. There are a number of facets of this. Part of it involves viewing Kiyoi as basically perfect–outstanding in every way. Even when Hira sees Kiyoi as cruel, he seems to view this as an ideal attribute for someone like Kiyoi.

Hira not only states that he thinks of Kiyoi as “like a God" in season 1, episode 6, he frequently expects Kiyoi to have god-like qualities and abilities. In one of Nagira Yuu's shorter pieces about Hira and Kiyoi that's told from Hira's perspective, he's explicit about this. "Kiyoi's existence is already in a much higher dimension than human beings," he thinks. "Is he the successful fusion of deity and human? That is the big question" ("Wonderful World," as translated by @sparkling-rain). At points during the series, he expects Kiyoi to have a superhuman degree of freedom to do anything he wishes and to know things that would require him to read Hira's mind. He really does treat him as if he’s practically omnipotent.

Hira's idealization of Kiyoi has a number of implications. One is that Hira misunderstands the social structure at his school. He views Kiyoi as the unquestioned king and doesn’t see that in many ways, Kiyoi makes choices about how to behave in school out of a desire to stay on the good side of bullies like Shirota. This fundamental misunderstanding in turn makes it impossible for Hira to notice or understand all the ways Kiyoi tries to protect him at school. If Kiyoi were really at the peak of the school hierarchy, if he wanted to be nice to Hira, he would just do it. But because he has to maintain a certain image in order to keep himself safe, he has to help Hira in covert ways. For example, when Kiyoi admonishes Yoshida not to order Hira around or use his demeaning, ableist nickname, he makes it seem like he just wants Hira to be at his beck and call, which wouldn’t be possible if he were occupied doing tasks for others. But if that were the case, why would he object to Yoshida using the nickname? For that matter, why doesn’t Kiyoi ever use the nickname himself? (He says it aloud in his exchange with Yoshida, but he never actually uses it to address Hira.) If Hira weren’t so invested in the idea of Kiyoi’s supreme power, he might have noticed these disparities between his narrative and reality within the story.

In season 2, the fact that Hira is both someone who has a relationship with Kiyoi and at the same time is a fan of Kiyoi as a performer points out another aspect of idealization. While I’ve never seen Kohut’s concept of idealization applied to fandom, I think there’s at least a variation of it at play when we feel comforted by, or as if we gain status from, being a fan of a person (or a group, piece of media, etc.) that we see as special or powerful. When we get excited because the sports team we root for does well or our favorite actor wins an award or is in a movie or show that does well, I think we’re experiencing a kind of gratification based on a selfobject that we feel is ideal in some way. Our status as fans gives us an affiliation that feels similar to a real connection. (Parasocial relationships are related to this as well–something that’s likely to resonate with those of us who participate in BL fandom, where examples of parasocial relationships abound.)

So both as a fan and as a classmate, then a (sort of) friend, then a boyfriend, Hira gets a great deal of satisfaction and happiness from idealizing Kiyoi and feeling like he has a kind of tie to him. This is completely interwoven with the love he feels for Kiyoi in the beginning. But it also makes it very difficult for him to acknowledge the ways in which Kiyoi doesn’t actually resemble his initial, idealized selfobject of him. Kiyoi isn’t omnipotent. He was never actually the most powerful person in their high school class. In many ways, he’s actually a better person than his selfobject version. Although Kiyoi isn’t the nicest person ever, he’s not nearly as cruel as the cold, imperious figure Hira paints him as.

Sometimes Hira chooses this selfobject over Kiyoi the human being, and Kiyoi knows it. In season 1, episode 4, when Hira starts to get close to Kiyoi but then backs off, protesting that he’s just a “servant” and Kiyoi is his “king,” Kiyoi responds by telling him (in the Viki subtitle translation), “I don’t care if you chase your ideal of me, but leave the real me alone.” This dynamic, of course, is a huge theme in their relationship that continues all the way to the end of season 2 and beyond.

Those are some of the ways in which Hira insists on maintaining his idealized selfobject of Kiyoi. But there’s another way he clings to this idealization, which I think is harder to see at first: in order for Kiyoi to be elevated, Hira has to be beneath him. This is actually one of the most paradoxical parts of this paradoxical structure, because in Hira’s view, he has to be beneath Kiyoi in order for Kiyoi to be exalted, but by exalting Kiyoi, Hira’s status is raised. It sounds strange at first, but it’s not a new idea. The notion of humbly dedicating oneself to someone or something that you uphold as an ideal sounds like an act of self-abnegation, but in the minds of those who take on such a role, by affiliating themselves with this perfect person or thing, some of the magical aura of that perfection rubs off on them.

It’s a bit like members of the clergy in the past (in a Christian/European context), who were known to humble themselves completely, taking vows of poverty, depriving themselves in various ways, even mortifying their flesh. Through these humbling acts, these people were seen by themselves and others as closer to God than an ordinary person, potentially as a channel to God–even as someone who could actually speak for God. By humbling themselves and exalting their ideal, they became something greater than they would ever have been capable of being on their own. Hira’s approach is remarkably similar. In keeping with his description of Kiyoi as a kind of god, he talks about wanting to be a “nun.” (As I understand it, he’s describing a role more like that of a shrine maiden in Shintoism than a nun in any Christian tradition, but there’s enough similarity in those roles to justify the translation.) Basically, if you make your ideal person perfect enough, then even being their servant gives you a lot of status, especially if you’re their most devoted, indispensable servant.

I’m reminded of a passage from the novel here. In the novel version of the story, Kiyoi visits Hira at his new home. A different situation than the one in the series has led to him living alone for the first time, and as in the series, Kiyoi uses his need for a rehearsal space as an excuse to visit Hira there. The situation is somewhat different from the series, but similar in essentials. Hira and Kiyoi have a conversation that leads to an exchange that is equivalent to the conversation that takes place right after the finger incident in the series. In the novel, this scene is portrayed from Kiyoi’s point of view; anything in italics is his internal dialogue. (The ellipsis below is mine.)

‘What am I to you?’

‘The person I love most in the word.’

It was this firm response that gave Kiyoi courage.

‘Then, do you want to date me?’

Kiyoi felt his face burning. Just say yes. If you do, I’ll be able to be honest too. Kiyoi’s heart was pounding as he waited for Hira’s answer, but the answer he got was something that he hadn’t expected.

‘I don’t want to.’

Kiyoi blinked.

‘Why?’

…

‘Because you’re the king.’

‘Huh?’

Kiyoi’s eyes blinked even faster than before.

‘I mean…Kiyoi is like a king, and I’m merely an ordinary person who serves the king; it’s not like I do it out of obligation, but in my mind, I view myself as Captain Duck…Ah, by Captain Duck, I’m referring to a yellow toy in the shape of a duck that children play with in swimming pools or bathtubs, you know?’

–I know, but what does that have to do with it?

Not caring about Kiyoi, who wanted to ask something, Hira continued to explain about the duck. He kept babbling on and on about how Captain Duck once used to float in the sewage and was now proudly floating down a golden river as a prestigious toy of the king, and it was very satisfied with its current life.

(from this section of White Lotus’s novel translation)

Hira is explicit here about the servant/king relationship he envisions for himself and Kiyoi. But the rubber duck imagery is even more telling. Being a cheap toy, an inanimate object of so little value that it’s almost disposable, is more than enough for Hira as long as he can be associated with Kiyoi–if he can be ‘a prestigious toy of the king.’ Just belonging to Kiyoi, even (or especially?) as an insignificant object, equates to ‘proudly floating down a golden river.’ Again, placing Kiyoi in an exalted position and then abasing himself (while maintaining a link to Kiyoi) is Hira’s way of using idealization to achieve a paradoxical kind of status.

The conflict over Hira’s unrelenting idealization of Kiyoi comes to a head in season 2 when Hira fails to understand why his comment about Kiyoi and his parents having “nothing to do with one another” was hurtful.

Kiyoi: Do you not get how I feel right now?

Hira: I don’t!

Kiyoi: Think about it! If you don’t get it, think! [tapping Hira on the head]

Hira: Sorry.

Kiyoi: I don’t want you to apologize.

Hira: But…you’re mad at me.

Kiyoi: It’s always like this. I get mad, and you take the blame. But in reality you just don’t get it!

Hira: No, I don’t! The stars in the sky and the ones watching them will never align!

Kiyoi: What does space have to do with it?!

Hira: Because you and I are completely different! We’re in different dimensions and on different paths. That’s why stars shine so brightly! If I try to touch it or to understand it, all I’ll do is pull the star down to my level! So what I’m saying is…in reality…I don’t…want to understand you.

(dialogue translated by @lollipopsub)

Hira makes this dynamic very explicit here. It’s not just that he thinks Kiyoi is superior and his role is to serve him. He’s determined to actively resist interacting with Kiyoi on an even playing field. It’s particularly clear when he says, “If I try to touch it or to understand it, all I’ll do is pull the star down to my level.” Seeing things from Kiyoi’s point of view or touching him–metaphorically, and in some ways literally–would “pull [Kiyoi] down to [Hira’s] level.” Instead of raising Hira’s status, this would degrade Kiyoi’s. The distance between Kiyoi and Hira–the lack of understanding and meaningful contact–is (from Hira’s perspective) a feature, not a bug. It’s integral to the gratification Hira experiences when he watches Kiyoi as if he were a star–something both beautiful and trillions of miles away.

One sign of the importance Hira places on Kiyoi’s exalted social status is how irritated, even livid, he gets when other people don’t recognize and behave in accordance with his views on the social hierarchy and where they stand in relation to Kiyoi.

For example, when Shirota and his friends make shitty comments about Kiyoi after he doesn’t win the contest, they’re obviously being assholes. But what bothers Hira most is that they are acting as if Kiyoi failing to win a highly competitive national contest means he’s beneath them, when in fact, it’s unlikely any of them would have qualified as contestants, much less made it to the finals like Kiyoi did. To Hira, it’s their lack of understanding of their place in the hierarchy, their lack of recognition that Kiyoi is above them, that is most damning. Which is legitimately infuriating–they’re being incredibly arrogant. But personally, I think it’s clearly more important that they’re being critical and dismissive of someone they claim is their friend right when he has just gone through something very disappointing. That’s not a big concern for Hira, though. In addition to deriving a kind of status from his association with Kiyoi, he also finds some satisfaction in knowing that while his status in relation to Kiyoi is low, at least he can correctly gauge where he stands, unlike others.

And he seems to relish not only correctly assessing his place in the world but also maintaining a particularly lowly role. This isn’t inherent to idealization, though as I’ll talk about further, this combination of factors isn’t unique to Hira by any stretch. I mentioned that Hira’s perfectionism, among other things, is a way of attempting to, as Brene Brown put it, “avoid or minimize the painful feelings of shame, judgment, and blame.” Hira does have some grandiose beliefs about himself, but he also views himself as inferior in many ways. This tension creates the stuckness that often comes with perfectionism, and this blocks Hira from attaining goals that would fuel a more healthy kind of self-esteem. Gaining status through his association with an idealized version of Kiyoi gets around all of these problems.

Hira also seems to view his grandiose thoughts as a sort of jinx, a way of tempting fate. Think back again to his thoughts when he found out that he hadn’t made the first cut in the Young Photographica contest. “It felt like I was being ripped apart for being conceited.” In Hira’s world, having grandiose thoughts–or at least, buying into them–brings punishment. It’s better, and safer, to embrace total abjection. This is one more reason why it seems safest to put Kiyoi on a pedestal while placing himself in the most inferior position possible. At least, this seems safest until Hira realizes he could lose Kiyoi entirely if he doesn’t stop this destructive pattern.

When Hira does finally try to make a shift in how he relates to Kiyoi at the end of season 2, the big gesture he makes toward “look[ing] at [Kiyoi] straight on” is setting, then communicating, the goal of photographing Kiyoi in the role of professional photographer. This is a very appropriate way for him to make this move. Viewing Kiyoi more as an equal means having to relinquish some part of the status and self-worth he borrows from his idealized image of Kiyoi; this is the perfect time, then, for him to find some self-worth of his own by finally putting himself out there as a photographer and making a real effort to test his abilities.

That's it for this installment! I hope to get part 2 posted within the next week. Edited to add, four months later: That was a little unrealistic! But I'm determined to finish it off one of these days.

Edited to add:

Adding an edit here as I noticed what seems like a rather glaring omission. I failed to reference a scene that bears out a lot of what I have to say in this post. It happens when Hira is staying with Noguchi in Eternal. They have this exchange over ramen:

Noguchi: I was just like you in the past. All full of myself and thought that everything I saw was boring. I was always angry and all, "You're all worthless and should disappear!"

Hira: I don't think we're alike at all, though.

Noguchi: Having too much confidence and having too little confidence, they're two sides of the same paper in the sense that they're both signs of a damaged self-consciousness. Anything could make you switch sides at the drop of a hat.

(Emphasis mine.)

Citations for individual quotes are included with their respective quotes. The following sources were used:

When I quoted series dialogue, I used the wording @lollipopsub used in their (sadly no longer accessible in the US) fansub whenever possible. I lost access to this version so these quotes are from my notes.

I also quoted the Viki subs (which are good, just not quite as good as the ones @lollipopsub made) when needed. On one occasion I used the Viki version because it supported my point better.

When I quoted the novel, I quoted a fan translation by White Lotus featured on a site called Chrysanthemum Garden.

I also briefly quoted a short story translated by @sparkling-rain here.

When I quoted Eternal, I quoted a fansub that (at the subber’s request) will remain nameless.

#utsukushii kare#utsukare#utsukushii kare meta#utsukushii kare analysis#utsukushii kare season 1#utsukushii kare season 2#utsukushii kare 2#utsukushii kare eternal#my beautiful man#hira x kiyoi#psychology of bl#self psychology#heinz kohut#selfobject#covert perfectionism#narcissistic perfectionism#psychological paradoxes of utsukushii kare#hira kazunari

78 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

자기대상과 심리구조 발달: Selfobject and Development of Psychic Structures

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Text

Selfobject

Handwoven polyester, linen, sublimation dye, acrylic ink

2016

I really like the visual effect of Margo Wolowiec's use of hand-woven polyester, cotton and dye sublimation inks for the glitch art. The cotton gives a unique texture, while the dyeing of the ink is layered on the fibres and has a slender rendered beauty.

in her artist's statement. “Whether fractured memories are materialized into sculptural form, information is embedded into threads of woven cloth, or woven cloth is unraveled and fragmented into multiple different forms, tangible spaces are created that allow for a deeper contemplation of our evolving landscapes of immateriality.”

I have always felt that meaning does not migrate because of form, that a change in the form of expression brings only sensory changes, and that the meaning one tries to express when creating does not change. But for the viewer, the meaning is re-given by him/herself, the author's meaning is not the viewer's meaning, the viewer himself/herself will give meaning to the work, and this process is also a necessary part of the refinement of the work, the work we make may get unexpected comments, and after this part, then go on to self-appreciation and improvement.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Margo Wolowiec

Selfobject, 2016

Handwoven polyester, linen, sublimation dye, acrylic ink

Courtesy the artist and Jessica Silverman Gallery

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

We need selfobjects in our environment for emotional survival much as we need oxygen in the atmosphere for physical survival

-Heinz Kohut

0 notes

Text

Reflections on Winnicott & Jung

David Sedgwick, Winnicott’s Dream: Some Reflections on D. W. Winnicott and C. G. Jung.

Jung-the-psychotic-child is not true for most Jungians, who, while acknowledging that Jung had a difficult childhood, would disagree with Winnicott’s (over)diagnosis. Morey (2005), in a wide-ranging review of Winnicott’s review and the potential pitfalls for analytical psychology of Jungian/psychoanalytic syntheses, finds Winnicott’s diagnosis of childhood schizophrenia in Jung “untenable” (p. 340) and a “misdiagnosis” (p. 346). He suggests Winnicott is mistaking a “disturbing childhood” for schizophrenia. Feldman (1992), also a Jungian analyst, echoes this, emphasizing the necessity of Jung’s turning inward to find healing potential in the absence of a secure family or analysis. Storr (1973, p. 16), referring not to Jung’s childhood but to the post-Freud years, concludes that Jung “came near to having a schizophrenic breakdown” but used his “unusually strong ego” and creativity to counteract the “mental upheaval”. Similarly, from a combination self-psychological/Jungian viewpoint, Corbett and Cohen (1998, p. 317) propose that Jung’s mid-life nekyia may have been “prepsychotic” in form but that Jung had sufficient self-structures and selfobjects to integrate it rather than fragment.

https://www.cgjungpage.org/learn/articles/analytical-psychology/915-winnicotts-dream-some-reflections-on-dw-winnicott-and-cg-jung

1 note

·

View note

Photo

MARGO WOLOWIEC, Selfobject, 2016

218 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mirror-hungry personalities thirst for selfobjects whose confirming and admiring responses will nourish their famished self. They are impelled to display themselves and to evoke the attention of others, trying to counteract, however fleetingly, their inner sense of worthlessness and lack of self-esteem.

Las personalidades ‘’hambrientas de espejos’’ tienen sed de objetos personales cuyas respuestas de confirmación y admiración alimentarán a su yo hambriento. Se ven obligados a mostrarse y evocar la atención de los demás, tratando de contrarrestar, aunque sea fugazmente, su sentido interno de inutilidad y falta de autoestima.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Collective_narcissism

0 notes

Photo

What is a selfobject? http://bit.ly/2E4fldP

0 notes

Text

Azula papers I did years ago, final part

Azula would probably fit under the narcissistic personality category. Narcissistic people constantly need people’s opinions to tell them how good they are (McWilliams 1994). If other people think of them well, narcissistic people feel good about themselves but only temporarily. If they feel that they are thought about poorly it feels like the end of the world for them. Typical people do also have their pride enhanced and crushed by others’ judgments as well but narcissistic people take it to the extreme. They are preoccupied constantly about how others think of them. Despite all the praise that they may get, deep down they feel that they are unloved .

Azula, a princess, has quite a lot of power. She can order around guards at a whim. She constantly has her needs taken care of by her maidservants and hears a lot of praise from her supporters. McWilliams gives an example of a man described by Ernest Jones who showed such characteristics such as feeling omnipotent, over evaluating his creativity and not easily emotionally read. Azula similarly wants to show just how powerful and fearful she is by her firebending prowess, how much of a military tactician she is by successfully planning and executing that plan to take over another nation and there are times when her enemies cannot easily read her, at least early on in the show. This is confirmed by her ability to use a top tier firebending technique called lightning bending which, as her uncle told to her brother, can only be used when one does not feel any emotions at the moment. Azula is also considered a good liar, as even one of the heroes, who is able to feel when someone is lying, is not able to tell if Azula is honest or not.

Yet she has a fear that her friends will leave her, so she uses fear tactics to keep them with her. They appear to not mind this at first and do follow out Azula’s plans on how to take down the heroes and the other opposing nations that threaten the Fire Nation’s empire which confirms to Azula that she is good at what she does. Azula nearly breaks down when her friends betray her to help the heroes escape a maximum security prison meaning she does need the opinions of others to have the feeling that she is indeed amiable, competent and is able to control others including her friends. Though she does not like her mother, Azula hallucinates about her mother in her mirror, telling her that she does indeed love her. This shows that Azula did want her mother to outright tell her that.

McWilliams mentions about analysts who believe that narcissism stems from early disappointments in the relationship (1994). Her mother did not think too well of Azula and ran off when Azula was very young. Therefore she did not give much to the relationship. Also sometimes there is a higher chance one becomes narcissistic if he or she is used by a parent or other family member as an extension of himself or herself. Azula’s father, Ozai, may have likely used her for that purpose. He is proud of her firebending skill and is not too happy about his son’s lack of talent. Ozai himself is no slouch at firebending so he sees himself in his daughter. Perhaps Azula unconsciously fears failing and being shamed like her brother. McWilliams gives an example of a son not seeing what is wrong with his father’s position in only choosing a doctor or a lawyer as a career choice because he was treated like an extension his whole life. Likewise Azula does not see anything wrong with success as an only option and can not stand the thought that others do not support her endeavors.

People use selfobjects in order to get a sense of identity by defining who they are by having selfobjects approve or admire them. According to self psychologists, everyone uses selfobjects. The difference between normal people and narcissistic people is that due to moral reasons, normal people do not want to use people for just what they can do for the relationship. Narcissistic people may only see others just for that purpose and nothing more. Azula does consider them her friends, but she mostly uses them to reassure herself that she is lovable and capable of many things. She gets devastated when they leave her. Some believe that those who use others for this purpose were due most likely to being used themselves. When Azula and her brother were showing off their firebending skills early in their childhoods, Ozai saw his daughter as an extension of himself due to her talents and pushed Zuko, his son, away for his failures.

Narcissistic people have defenses in order to maintain their self-esteem. Two of them are idealization and devaluation and normally they complement each other. Azula idealizes her capabilities to control others, plan and execute those plans. She also idealizes her father. People with narcissism may boost their identity by seeing another as perfect and connecting with them as Azula does with her father. On the opposite side of the spectrum, Azula devalues her enemies, her uncle, her brother and later on her friends for leaving her. She tells the guards to let them rot in prison showing that in her eyes they are now at the level of some of the worst criminals.

With all her issues, how well is Azula functioning? She does not seem to need the opinions of everyone in order to function. She must know that her enemies do not think too kindly of her. Then again, she does not need to care about the moral consequences of killing them as they are dehumanized in the eyes of the Fire Nation. She is also only betrayed by two people. Does she really need to care about their opinion so much? After all, she has guards, maidservants, and her father to back her up. It does seem that her friends mean a lot to her. She is fearful that her guards and maidservants are out to get her and may plan an assassination attempt. If her friends left her, what is stopping others from doing unspeakable things to her? Azula therefore is barely able to take stressors well.

She still has her firebending expertise. Even that is undermined when her brother triumphs over her in the final duel. She gets chained up at the end and viewers witness her breakdown. She cries, screams and breathes out fire out of anger as her brother and one of the heroes watch her and sigh at how far she has fallen. I would say that Azula is on the neurotic level. Those who are neurotic normally can understand the difference between reality and fantasy. She is able to pass as a functioning individual, at least in her society but she does have issues with anxiety and how others think of her. Azula is able to understand that the reality is that she lost and the heroes won and that she is not in a fantasy world where she still all powerful.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Kohut - Self Psychology Readings

“SELFOBJECT” NEEDS IN KOHUT’S SELF PSYCHOLOGY & Links With Attachment, Self-Cohesion, Affect Regulation, and Adjustment

http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.523.1537&rep=rep1&type=pdf

An Infant's Experience as a Selfobject

(References are helpful in this article)

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/6caf/ee11daac8cf4b4c60ba781b3fa0e0d3cb71b.pdf

Sort of superficial explanations of wikipedia

http://www.wikizero.biz/index.php?q=aHR0cHM6Ly9lbi53aWtpcGVkaWEub3JnL3dpa2kvU2VsZl9wc3ljaG9sb2d5

0 notes

Text

True Companion

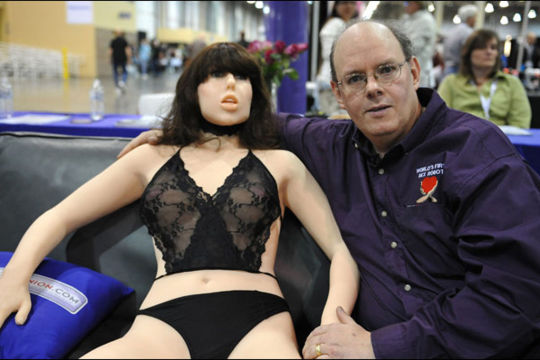

Sherry Turkle claimed that robotic companionship is not as good as the roboticists proposed before. She has discussed the harms of this kind of companionship toward children and adults with the examples of the AIBO robot dog and the sex robot Roxxxy respectively.

Robotic companionship might be more dangerous to children than adults as Turkle believed that growing up with robots in roles traditionally reserved for people is different from coming to robots as an already socialized adult. Children need to be with other people to develop empathy and mutuality; interacting with a robot cannot teach these. The fact that children can not learn empathy through interacting with robots is because the first thing missing if you take a robot as a companion is alterity, the ability to see the world through the eyes of another. Without alterity, there can be no empathy. Relational artifacts which refer to sociable robots here are only the selfobject of people that is cast in the role of what one needs. There is no alterity as robots just mirror the thoughts and needs of the people. What’s more, if you don’t feel different from others, it would be hard for you to have a sense of sympathy for others.

AIBO is a series of robotic pets designed and manufactured by Sony. With a price tag of $1,300 to $2,000, AIBO has entered the market which can provide companionship to the owners and can be seen as a harbinger of the digital pets of the future. AIBO presents that it has its own feelings as it can express its negative emotion through flashing its eyes with the color of red. People can pet AIBO, can play with it and even talk their thoughts to them. However, children are learning a way of feeling connected in which they have permission to think only of themselves while enjoying the companion of AIBO because AIBO permits children attachment without responsibility which is different from the traditional animal pets.

youtube

Robotic companionship is also not true companionship towards adults. Roxxxy, termed a “sex robot” is a full-size interactive sex doll which was built and designed by Douglas Hines. Roxxxy is not limited to sexual uses as she can talk to you, listen to you and feel your touch. The robot's vocabulary may be updated with the help of a laptop and the Internet. Roxxxy might be more attractive to the less social people than others as Chapman (2015) has found out that, “Socially disconnected people have a stronger tendency to anthropomorphize robots.” However, Turkle believes that Roxxxy can bring more harm than goodness to people because there is no true love or true companionship between them.

From my point of view, I agree with the author’s stand. I also think the robotic companionship is not that good and it might make people become more fragile and isolated. Dependence on a robot presents itself as risk free. However, when one person becomes accustomed to “companionship” without demands, life with people may seem overwhelming for that person. Although dependence on a person is risky, which makes us subject to rejection, it opens us to deeply knowing another. Robotic companionship may seem as a sweet deal, but it consigns us to a closed world—the loveable as safe and made to measure.

References:

Arendt, M. (2015). My dear robot – anthropomorphism and loneliness. Sara Coleridge.

Turkle, S. (2017). Alone together: Why we expect more from technology and less from each other. New York: Basic Books.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bl4IDI86p_0

0 notes

Quote

None of this came as a real disappointment: I had never expected her to talk to me about the paintings; I knew I had no appeal for her, and no chance for ever making her like me; the most I had been able to hope for was that, since I would not be seeing her again before leaving Paris, her kindness would leave me with a deeply soothing impression of her, which I could take with me to Balbec as something of indefinitely lasting value, intact and not as a memory mixed with anxiety and dejection.

Marcel Proust, The Guermantes Way, p. 270

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Azula papers I did years ago part 3

Kohut talked about normal narcissism, a certain time in life when infants first experience themselves and their beloved, usually their parents, as omnipotent who all have the power to do anything they want shall they will it (Mitchell & Black 1995). Later, rather than telling the children outright that their outlook on life is false, they learn for themselves, step by step that they and their parents are limited in the power they have. They then learn to adapt to disappointments, not overreact and develop coping skills against the stresses of life. Azula, being a princess, most likely had access to maidservants as an infant so she had no problem with thinking that she is all powerful. It is pretty reasonable to assume that she fantasized herself as a very powerful Fire Lady and had imagined that all her subjects are obeying her without question. We also have her father whose lineage managed to wipe out an entire nation, he himself conquered another nation and he also already ruled a country before that. Though she had it all, Azula shows everything but healthy narcissism. She falls into despair right away if her plans backfire, showing behaviors such as instantly throwing her childhood friends into prison or dismissing her servants. She appears to show self-aggrandizing narcissism instead, thinking of herself as the authority on everything and everyone has to fear her. She may have not had the experience of learning that she is not all that powerful like most other children because maybe nearly all her childrearing was done by servants rather than her parents. Her father is busy ruling a few nations and her mother seems to not be at all close to her, choosing to be with her brother instead so she did not get the necessary attention from her parents except when she showed off her talents to her father.

Azula also has difficulty expressing concern for others. The Fire Nation managed to occupy a city named Omashu. The king there gets imprisoned and now all the people are under the rule of a Fire Nation governor. The heroes devise a plan to fool the Fire Nation occupants into believing the original residents of the city had an incurable epidemic and the governor releases the citizens from the city as a result. Unfortunately the governor’s child wanders out as well. The heroes agree to give the governor’s family back their son in turn for the king and the family accepts. The governor also has another daughter named Mai who is Azula’s childhood friend. Azula decides to be the one who will do the trade because she fears that the governor will mess up again as he did when he was tricked into releasing all the citizens and she takes Mai along with her. They both meet up with the heroes to do the trade. Azula then says that the deal is off because she considers trading a powerful king who can control elements of the earth for a two year old child unfair and she does not seem to care that this is her friend’s brother.

Oddly enough Azula barely talks about herself despite thinking she is all mighty. Instead she tells everyone about her father’s supremacy. She tells the governor that her father Ozai trusted him with Omashu and he failed him. She decides to rename the city New Ozai after her father. Maybe she is really talking about herself after all, but indirectly. Kohut talked about selfobject transferences which he defined as a phenomenon when people see other objects or people as extensions of themselves (Mitchell & Black 1995). Kohut talked about three types of this transference and one of them is called idealizing transference. Idealizing transference is when a person regards another as powerful and the person feels proud to be connected to this impressive entity. Azula is honored that she is the daughter of a ruler and therefore thinks she is glorious as well.

Another kind of transference is mirroring which is when a person needs another to understand and acknowledge her and reflect back her experiences (Mitchell & Black 1995; Rowe). Azula’s father did acknowledge her fire controlling talents and military plans but that was not sufficient enough for her wellbeing. She needs someone who really understands her motives and struggles and she did not get an actual person to do that. What she gets is a hallucination of her mother who recognizes her need to use fear to control people and that she is indeed loved by her mother. She sees this hallucination, amusingly, in a mirror. A third type of transference Kohut mentioned is the twinship transference, which is when one wants to feel a likeness to the selfobject (Mitchell & Black 1995; Rowe). The selfobject shares “similar ideas, values and goals” (Rowe, p. 47). Indeed, Azula and Ozai similarly are controlling and will do anything to get what they want. Her father likes Azula’s idea of eradicating the entire Earth Kingdom, just like his grandfather wiped out the Air Nomads, the only nation that is a threat to the Fire Nation and decides to go with his daughter’s plan.

1 note

·

View note