#seafaring

Text

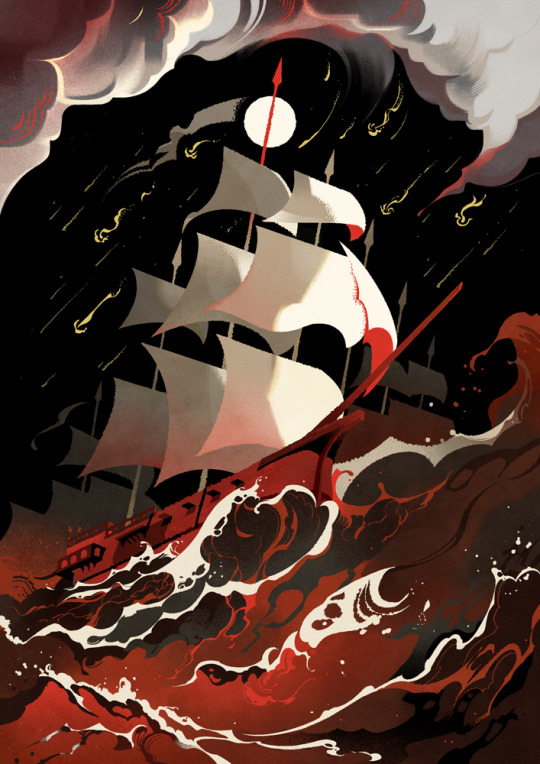

The despotic fleet, one of the main adversaries of the Dioscorian agents 🔥 The Hidden Isle

#illustrators on tumblr#artists on tumblr#illustration#ttrpg#the hidden isle#indie rpg#ttrpg community#nautical#maritime#seafaring#sefirot tarot#Sefirot#ocean

10K notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey. What's a sea pilot? Isn't that what the captain's for? Why did the boat get all the way to open sea without a pilot?

???

I live in a 4,000m high landlocked mountain, please excuse my lack of nautical knowledge

Don't worry, you're completely fine, few people who aren't in a nautical job know what a sea pilot is! To understand what a pilot does, you first have to understand that captains very rarely steer the ship, that is the job of the first mate (depending on ship size, this may wary). Their job is to give commands to the crew both on deck and in the engine, to keep the ship running smoothly and for it to go where it needs to go. and while the ship master's certificate prepares you for almost all situations on sea, there are certain areas, especially canals or harbors, that require specialized knowledge and experience just with that area to navigate safely.

that's when a pilot comes in! when a ship of a certain size or with certain dangerous cargo enters their waterway, the come on board and assist the captain in driving through the area, often taking over commands, communications or even steering in some situations. they have to have specialized training and have to have up to a decade of experience as a captain themselves, depending on the jurisdiction. also, they are usually transferred on board by a much smaller pilot boat, meaning that you have to climb a rope ladder to get on board, which, depending on the swell, gets quite exciting. here are some pictures of me and my sister joining my dad to illustrate that point:

with 80% of wares being transported by sea, and almost every big harbour requiring sea pilots, i feel like this is one of the jobs that virtually nobody knows about that keeps the world trade going, and i think they should get more recognition!

#nautical#seafaring#thanm youuuu for the question i am of course not an expert i just get to go with my dad to work sometime. but its cool as shit

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

We are out here.

#sailing#sailing ship#seafaring#tall ship#hudson river sloop clearwater#sailboat#sloop clearwater#sloop

172 notes

·

View notes

Text

One day out of pure curiosity I googled "world's first diving suit" and was greeted with this.

And I was never the same.

"John Lethbridge (1675–1759) invented the first underwater diving machine in 1715. He lived in the county of Devon in South West England and reportedly had 17 children. He is the subject of the Fisherman's Friends song "John in the Barrel".

John Lethbridge was a wool merchant based in Newton Abbot who invented a diving machine in 1715 that was used to salvage valuables from wrecks. This machine was an airtight oak barrel that allowed “the diver” to submerge long enough to retrieve underwater material."

176 notes

·

View notes

Text

#wool sweater#wool turtleneck sweater#sweater#wool#shetland sweater#menswear#crewneck shetland#shetlandsweater#shetland#shetland crewneck#wool turtleneck#turtleneck#high neck sweater#seafaring#captain

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Picture an epic ship, lost in the Aegean Sea's abyss for millennia. The Dokos shipwreck is the oldest known shipwreck found. This remarkable archaeological gem offers a glimpse into an era of seafaring, trade, and tales of adventure.

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

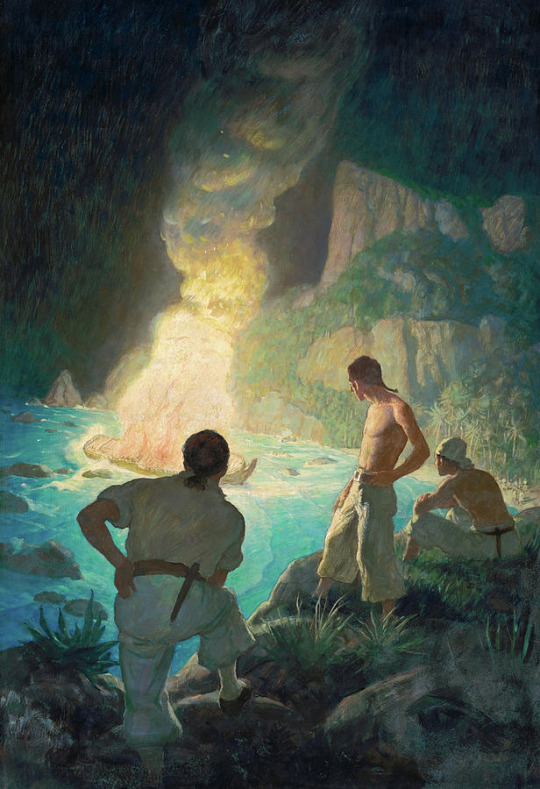

N.C. Wyeth

The Burning of the Bounty

1940

#n.c. wyeth#book illustration#mutiny on the bounty#book illustrator#fletcher christian#art history#american art#aesthetictumblr#tumblraesthetic#tumblrpic#tumblrpictures#tumblr art#tumblrstyle#artists on tumblr#tumblrposts#aesthetic#history#maritime history#maritime#seafaring#mutiny#ocean voyage#captain bligh

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Argo

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

#sea#ocean#water#nature#waves#sailor#seafarer#seafaring#sailing#knowledge#wisdom#wanderlust#art#travel

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

#nautical#ship#sea#pirate#pirates#pirate aesthetic#seafaring#sea travel#piratecore#seacore#oceancore#sailor aesthetic#sailorcore#nauticalcore#sea aesthetic#vintage

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

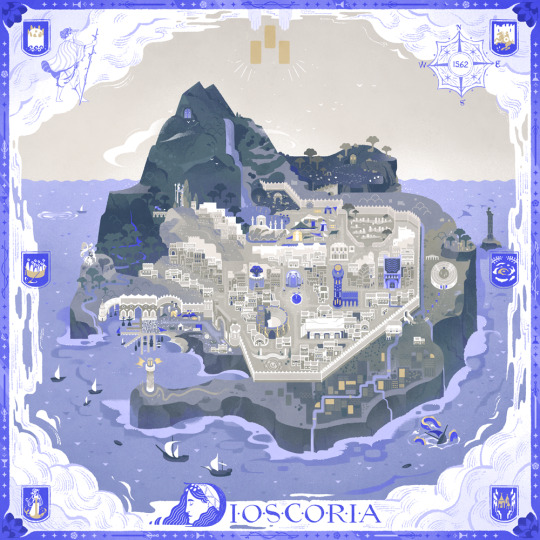

Discoria - The Hidden Isle 🌊

#illustrators on tumblr#artists on tumblr#illustration#ttrpg#the hidden isle#indie rpg#ttrpg community#island#map#nautical#maritime#seafaring#maps#sefirot tarot#Sefirot#had so much fun working on this map even though it took forever I'm so proud of it!#feel free to check out our newest Sefirot project

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

The 3-masted schooner Victory Chimes is down from Maine.

#sailing#seafaring#sailing ship#tall ship#this is a schooner appreciation blog#schooner alert#this is a schooner appreciation post#schooner#3-masted schooner#victory chimes

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

how i live

I woke at midnight, last night, to a hard sou’westerly and the floor moving in three directions at once — pitching, rolling, rising-and-falling. Now, six hours later, the wind has moderated. Everything is still. The rest of the world is obscured by grey mist and sporadic showers, as if the sky has fallen across the shore.

I climb up a short ladder to the companionway to check that all is well on deck — it’s the first thing I do every morning — then I return to my bunk to download email and read a couple of news sites on a laptop before my wife wakes and we have a cup of coffee together across the varnished teak table that separates our bunks.

We talk about what we want to do today and waste a minute or two trying to agree a time-table before giving up. For half a decade, we have scraped by with a minimum of routine or planning. We are singularly unadept at making lists or coordinating diaries. We end up doing most things together. Today, we will pick up some paint and shackles at a chandlery and find a local metal fabricator to repair or replicate a damaged stainless steel stanchion. We also have to buy some groceries. But first I want to repair our rubber dinghy.

My wife and I live on a 32-foot sailboat. It is a life-raft of sorts. It is also an island on which we are trying to regain an unsettled but sheltered freedom after several years of being homeless. Most days, we feel like castaways, with no hope of ever being rescued.

It’s hard to explain how we ended up here. Moving aboard was not a ‘lifestyle choice’ but an act of quiet desperation. We had dropped out of a life in which I had somehow ended up running two well-known, medium-sized companies, one of them publicly listed — before those roles, I had been a musician, gambler, seaman, smuggler, photographer, magazine editor, and governmental adviser — and we had taken to wandering slowly across Europe, the UK, and North Africa. After a year holed up on the southern coast of Spain, a few miles east of Gibraltar, riding out the worst of the pandemic, we moved to southern Italy, where we acquired, and set about restoring, a small ruin, part of servants’ quarters attached to a 16th century Spanish castle, in a village not far from Lecce, in Puglia. We had just completed the work, two years later, when the local Questura, the office of the Carabinieri that oversees Italian immigration, rejected our third application for temporary residence and issued a formal instruction to us to leave Italy — and Europe’s Schengen zone.

The boat was not something we thought through in any detail. I had spent a lot of time at sea in my youth and had lived on sailing boats of various sizes on the Channel coasts of England and France, as well as in the Mediterranean. Which is to say, I had an understanding of their discomforts. But the prospect of resuming a life that, before we ended up in southern Italy, involved moving every three months — not just from one temporary accommodation to another but from one country to another, so as not to contravene the terms of our largely visa-less travel — had exhausted us. I made an offer on a cheap, neglected, 45-year-old, fibreglass sloop I had come across online and organised a marine surveyor to look it over for me. He gave it a cautious thumbs up.

I won’t forget my wife’s dolorous expression, a month later, when she saw the boat for the first time. It was in an industrial area of Southampton, on a dreich morning in early spring — bitterly cold, windy, and raining. Around us, the Itchen River’s ebb had revealed swathes of black, foul-smelling mud. Raised far from the sea, on the plains of north-eastern Oklahoma, my wife told me later she had been praying that our journey to this glum backwater was part of some elaborate practical joke.

There is a whole genre of YouTube videos created by those who live on sailboats full-time and voyage all over the world. The most popular, the so-called ‘influencers’, are young(ish) couples or families with capacious, often European-built, plastic catamarans or monohulls. Their videos focus less on the gritty, day-to-day grind of boat maintenance and passage-making and more on sojourns in ancient, stone-built harbours in the Mediterranean, white, sandy beaches and palm-fringed cays in the Caribbean, or improbably blue lagoons and solitary atolls in the South Pacific, where they barbecue fresh fish, paddle-board, kite-surf and practice yoga and aerial silks for the envy of hundreds of thousands of followers. My wife’s and my life aboard together is nothing like any of this.

We are both in our sixties — I am just a year away from seventy — and we have spent more than a decade on the move around the world, at first following eclectic opportunities for employment then, when those opportunities receded, in search of somewhere we might be able to settle with very little money. Four months after moving aboard our boat, we still think of ourselves as vagabond travellers, our boat a shambolic, floating vardo that we haven’t yet managed to turn into a home. We’re not really ‘cruisers’, despite the sense of community we sometimes find among them, but we are seafarers — historically, a marginal existence driven by necessity. A recent, 150-nautical-mile passage westward along the south coast of England was a shakedown during which we learned how to make our aged, shabby vessel more comfortable and easier to handle and to trust her capacity to keep us safe at sea.

She bore the name Endymion when we bought her — after my least favourite poem by John Keats (“A thing of beauty is a joy forever…”) — but we re-named her Wrack. Depending on the source, ‘wrack’ describes seaweeds or seagrasses that wash up along a shore or the scattered traces of a shipwreck, either of which might be metaphors for my wife and me in old age. It is certainly how we feel when we’re not at sea. Life aboard Wrack is spartan — fresh water stored in a dozen polyethylene jerry cans, no hot or cold running water, no refrigeration and when the temperature drops, no heating either — so, from time to time, we concede the cost of berthing in marinas to gain access to on-site laundries, showers, flushing toilets, and wi-fi. Whether we’re berthed or anchored somewhere, we shop for food once a week — mainly vegetables, fruit, bread, pasta, and rice but little dairy and no meat — and eat one meal a day, cooked in the mid-afternoon on a two-burner gas stove.

The days we spend in close proximity to others’ lives ashore remind us how disenfranchised ours have become. We were homeless before we acquired Wrack, but now we are without a legal residence anywhere, even in our ‘home’ countries. We enter and exit borders uneasily as ‘visitors’, our stays limited to 90 or 180 days, depending on where we are. We have no access to banking, insurance, social services or, with a few exceptions, emergency health care. Even the modest Australian pensions we have a right to can only be received if we have been granted residence in countries with which Australia has reciprocal arrangements — and we haven’t. It’s hard even for other live-aboards to understand how deeply we are enmired in this peculiar bureaucratic statelessness. It’s harder for us to deal with it every day.

But life afloat provides consolations. We are ceaselessly attuned to the weather and our boat’s responses to subtle shifts in the sea state, tide and wind even when we are tethered to a dock. We appreciate the shelter — and surprising cosiness — the limited space below decks affords us but the impulse to surrender to the elements and let them propel us elsewhere is insistent. Our best days are offshore, even when the conditions are testing; the world shrinks to just the two of us, our boat and the implacable, mutable sea around us. Whatever problems we face ashore become, at least for the duration of a passage, abstract and insignificant. We sail without a specific destination — ‘towards’ rather than ‘to’, as traditional navigators would have it — and without purpose. Time drifts.

At least half of every day is spent maintaining, repairing, or re-organising the boat, an unavoidable and time-consuming part of our days, especially at sea. When we’re at anchor or berthed in a marina, we do what we can to sustain ourselves. Most afternoons are spent prospecting for drips of income from journalism and crowd-funding — a source inspired by those younger YouTube adventurers — or adding a few hundred words to a manuscript for a non-fiction book commissioned by a Dutch publisher, whose patience has been stretched to breaking point. Because of our visitor visa status, we can’t seek gainful employment ashore, and we have long since lost contact with any of the networks that once provided us with a higher-than-average income as freelancers. Our existence, by any definition, is impoverished and perilously marginal, we have little social life, yet we make the effort to appreciate our circumstances, even if it’s just to sit together in silence and absorb the elemental white noise of wind and sea, to do nothing, to not think.

Our precariousness burdens our four adult children, who have scattered to San Diego, Sydney, Berlin and Rome: “Where are you now?” our youngest asks. “How long will you be there?” We speak to each at least once a week. Not all of them long for fixedness but they do want desperately for us to have a ‘real home’, somewhere we can assemble occasionally as a family. We will be grandparents for the first time, soon. Like our few friends, our children worry that we might become lost — in every sense.

My wife and I are uncomfortably aware of our financial and physical vulnerability but at our ages, we can no longer cling to the faint hope that there’s an end to it. We have committed to an unlikely, reckless voyage. All we can do is maintain a rough dead reckoning of its course and embrace the uncharted and the relentless unexpected.

First published in The Idler, UK, 2023.

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

1936 French Line C.G.T. Southampton To New York

Source: transpressnz.blogspot.com

Published at: https://propadv.com/shipping-ad-and-poster-collection/french-line-poster-and-ad-collection/

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

#007: Seafarefly

If you're on a trip in the middle of the sea, you might spot one of

these flying above the water, miles away from any land, nobody knows why

they do this, or where they're going, but they seem to like the high seas! Some

smaller creatures like to hop on them as means of transportation.

Inspired by the fact real life butterflies can be seen flying over the sea without any landmasses nearby whatsoever!

Drawing Commandyceps gave me an excuse to revamp Seafarefly! I've wanted to ever since I first posted them, this is what they used to look like!

#creature design#species design#butterfly#butterflies#pirate ship#ships#nimalings#seafarefly#seafaring#fakemon#fakedex

4 notes

·

View notes