#punjabi film 2022

Text

#punjabi#punjabi songs#latest punjabi songs#latest punjabi movies#punjabi movies#new punjabi movie#punjabi actors#latest punjabi movie#punjabi song#new punjabi songs#punjabi movie#punjabi cinema#punjabi movie 2022#new punjabi movie 2022#punjabi film 2022#latest punjabi movie 2022#latest punjabi movies 2022#punjabi music#ptc punjabi#punjab#punjabi singers#new punjabi song#ptc punjabi film awards#punjabi romantic songs#ptc punjabi music awards

0 notes

Video

youtube

Song: Kasam

Movie: Lover (2022) [Punjabi]

Starring: Guri, Ronak Joshi

Music: Snipr, Lyrics: Babbu

Singer: Hashmat Sultana

-- Kasam : Hashmat Sultana (Full Song) GURI | Lover Movie Releasing 1st July | Geet MP3 (via Geet MP3)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ace Week 2023 Day 7:

No one is watching my videos so here's some a-spectrum representation re: Finnish.

Aka Finnish literature with a-spec characters; literature and poetry translated to Finnish/by Finns; a film and a webseries.

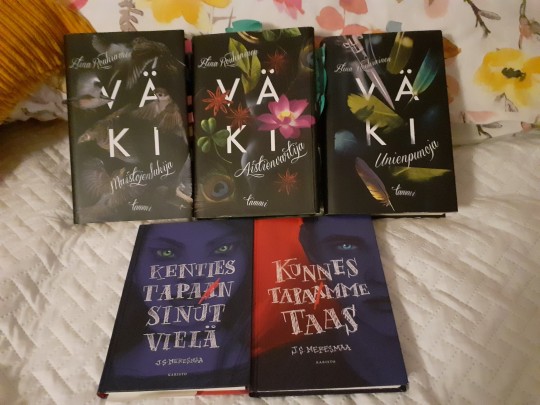

Väki trilogy(2018-2020) Elina Rouhiainen: Bollywood, aro not ace, genderqueer, brown (Punjabi). Sense manipulation.

Tapa(a) books(2022-2023) J.S. Meresmaa: Nora, agender and asexual 130+ year old vampire. Sims enthusiast.

Mähän tiesin ettei täällä ole mitään (2022) Kuura Juntunen: Leeni, asexual girlfriend to nonbinary Helle.

Lukitut (2020) Salla Simukka: Vega, aro. Johannes & Meea, demisexuals. (Have not read yet)

Freestyle (2023) Dess Terentjeva: Kai, aroace dancer.

Kaapin Nurkista (2022) Eve Lumerto: multiple, mainly Jaro Elomaa & Alina Linnanen

Jenna Clare, Water Runs Red, Finnish American, asexual, poet and youtuber.

Amanda Lovelace, asexual poet. The Princess Saves Herself in This One

Alice Oseman, aroace artist. Solitaire.

Elizabeth Hopkinson, asexual, edits asexual fairytales and myths into collections. Miracle of Marjatta in Asexual Myths and Tales

Tytöt tytöt tytöt/ Girl Picture (2022). Reetta Rönkkö is possibly asexual. Directed by Alli Haapasalo

Ace & Demi webseries (2023-). Alyssa/Ace is aroace and Demitria/Demi is demirose. Laura Eklund Nhaga also wrote related audiobooks in Finnish and English.

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pakistani cinema made history last year when Joyland (2022), written and directed by Saim Sadiq, became the first Pakistani film to premiere at the 2022 Cannes Film Festival, receiving a standing ovation and international acclaim. During its festival circuit, Joyland received several prizes and was shortlisted for the Academy Awards but was banned in its home country. Despite previous clearances from federal and provincial censorship boards, distribution of the Punjabi-language film was halted by the Pakistani government last November as the film consisted of “highly objectionable material” including scenes of LGBTQ+ intimacy.

While Pakistan’s Federal Censor Board quickly reversed the nationwide ban three days later with “minor cuts” to the film’s more controversial scenes after immense criticism for censorship on social media, the Punjab Censor Board ultimately prohibited the film from being screened in the province of Punjab, where the film is set and filmed.

Now, New Yorkers can watch the contested film at Manhattan’s Film Forum theater.

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gulf migration is not just a major phenomenon in Kerala; north Indian states also see massive migration to the Gulf. Uttar Pradesh and Bihar accounted for the biggest share (30% and 15%) of all Indian workers migrating to GCC1 countries in 2016-17 (Khan 2023)—a trend which continues today. Remittances from the Gulf have brought about significant growth in Bihar’s economy (Khan 2023)—as part of a migrant’s family, I have observed a tangible shift in the quality of life, education, houses, and so on, in Siwan. In Bihar, three districts—Siwan, Gopalganj, and Chapra—send the majority of Gulf migrants from the state, mostly for manual labor (Khan 2023). Bihar also sees internal migration of daily wagers to Delhi, Bombay, and other parts of India. Gulf migration from India’s northern regions, like elsewhere in India, began after the oil boom in the 1970s. Before this time, migration was limited to a few places such as Assam, Calcutta, Bokaro, and Barauni—my own grandfather worked in the Bokaro steel factory.

Despite the role of Gulf migration and internal migration in north Indian regions, we see a representational void in popular culture. Bollywood films on migration largely use rural settings, focussing on people who work in the USA, Europe, or Canada. The narratives centre these migrants’ love for the land and use dialogue such as ‘mitti ki khusbu‘ (fragrance of homeland). Few Bollywood films, like Dor and Silvat, portray internal migration and Gulf migration. While Bollywood films frequently centre diasporic experiences such as Gujaratis in the USA and Punjabis in Canada, they fail in portraying Bihari migrants, be they indentured labourers in the diaspora, daily wagers in Bengal, or Gulf migrants. The regional Bhojpuri film industry fares no better in this regard. ‘A good chunk of the budget is spent on songs since Bhojpuri songs have an even larger viewership that goes beyond the Bhojpuri-speaking public’, notes Ahmed (2022), marking a context where there is little purchase for Gulf migration to be used as a reference to narrate human stories of longing, sacrifice, and family.

One reason for this biased representation of migration is that we see ‘migration’ as a monolith. In academic discourse, too, migration is often depicted as a commonplace phenomenon, but I believe it is crucial to make nuanced distinctions in the usage of the terms ‘migration’ and ‘migrant’. The term ‘migration’ is a broad umbrella term that may oversimplify the diverse experiences within this category. My specific concern is about Gulf migrants, as their migration often occurs under challenging circumstances. For individuals from my region, heading to the Gulf is typically a last resort. This kind of migration leads to many difficulties, especially when it distances migrants from their family for much of their lifetime. The term ‘migration’, therefore, inadequately captures the profound differences between, for instance, migrating to the USA for educational purposes and migrating to the Gulf for labour jobs. Bihar has a rich history of migration, dating back to the era of indentured labor known as girmitiya. Following the abolition of slavery in 1883, colonial powers engaged in the recruitment of laborers for their other colonies through agreements (Jha 2019). Girmitiya distinguishes itself from the migration. People who are going to the Arabian Gulf as blue-collar labourers are also called ‘Gulf migrants’—a term that erases how their conditions are very close to slavery. This is why, as a son who rarely saw his father, I prefer to call myself a ‘victim of migration’ rather than just a ‘part of migration’. It is this sense of victimhood and lack of control over one’s life that I saw missing in Bollywood and Bhojpuri cinema.

— Watching 'Malabari Films' in Bihar: Gulf Migration and Transregional Connections

#bhojpuri indentured history#malayalam cinema#bihari labour migration#gulf migrant labour#malayali labour migration#bollywood cinema#bhojpuri cinema

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! I'm looking for FCs that can fit a character that is tough, gruff and seems like they would only respond in one word sentences. I'm open to any gender and ethnicity, just need some help finding FCs that fit the quiet but tough vibe. thank you in advance!

Eric Bogosian (1953) Armenian.

Emilio Rivera (1961) Mexican.

Michelle Yeoh (1962) Chinese Malaysian.

Benjamin Bratt (1963) Peruvian [Quechua] / White.

Ming Na Wen (1963) Macanese / Malaysian Chinese.

Peter Dinklage (1969) - has achondroplasia.

Park Hee Soon (1970) Korean.

Clemens Schick (1972)

Andrew Lincoln (1973)

Daniel Wu (1974) Hongkonger.

Omar Metwally (1974) Egyptian / Dutch - has spoken up for Palestine!

Ito Hideaki (1975) Japanese.

Pedro Pascal (1975) White Chilean.

Chaske Spencer (1975) Yankton Dakota Sioux, Sisseton-Wahpeton Dakota Sioux, Lakota Sioux Nakoda Sioux, Nez Perce, Cherokee, Muscogee, White.

Nonso Anozie (1978) Igbo Nigerian.

Natasha Lyonne (1979) Ashkenazi Jewish.

JD Pardo (1980) Argentinian / Salvadoran.

Krysten Ritter (1981)

Alberto Guerra (1981) Cuban.

Dichen Lachman (1982) Nepalese Tibetan / German, English, some Scottish.

Riz Ahmed (1982) Pakistani - has spoken up for Palestine!

Brian Tyree Henry (1982) African-American.

Son Suk Ku (1983) Korean.

Cara Gee (1983) Ojibwe

Clayton Cardenas (1984) Mexican, some Filipino.

Asia Kate Dillon (1984) Ashkenazi Jewish / Unspecified - non-binary and pansexual (they/them) - has spoken up for Palestine!

Richard Cabral (1984) Mexican.

Jessica Matten (1985) Red River Metis of Cree and Saulteaux descent, Chinese, White.

Martin Sensmeier (1985) Tlingit, Koyukon, Eyak, White.

Rahul Kohli (1985) Punjabi Indian - has spoken up for Palestine!

Oliver Jackson-Cohen (1986) Egyptian Jewish and Tunisian Jewish / English.

Sonoya Mizuno (1986) Japanese / English, Argentinian.

Monica Raymund (1986) Afro-Domincan / English, Ashkenazi Jewish -is bisexual.

Deepika Padukone (1986) Konkani Indian.

Kyle Gallner (1986)

Kali Reis (1986) Wampanoag, Nipmuc, Cherokee, Cape Verdean - is two-spirit (she/her) and queer.

Michaela Coel (1987) Ghanaian - is aromantic - doesn't have social media but in 2022 she boycotted an Isr*el-sponsored film festival!

Lewis Tan (1987) Chinese Singaporean / Irish, possibly English.

Rob Raco (1989)

Daniel Kaluuya (1989) Ugandan.

David Castañeda (1989) Mexican.

Úrsula Corberó (1989)

JuJu Chan (1989) Hongkonger.

Hannah John-Kamen (1989) Nigerian / Norwegian.

Assad Zaman (1990) Pakistani.

Kiowa Gordon (1990) Hualapai and White - has spoken up for Palestine!

Sarah Kameela Impey (1991) Indo-Guyanese / British.

Kasamatsu Sho (1992) Japanese.

Hari Nef (1992) Ashkenazi Jewish - is a trans woman - has spoken up for Palestine!

Kawennáhere Devery Jacobs (1993) Mohawk - is queer.

Freddy Carter (1993) - has spoken up for Palestine!

Alex Høgh Andersen (1994)

Gabriel Basso (1994)

Ayo Edebiri (1995) Afro Barbadian / Nigerian - is queer.

Ambika Mod (1995) Indian.

Emilio Sakraya (1996) Moroccan / Serbian.

Tati Gabrielle (1996) African-American, 1/4 Korean.

Archie Renaux (1997) Punjabi Indian and British.

Lizeth Selene (1999) Mexican [Unspecified Indigenous, Black, White] - is genderfluid and queer (she/they).

Zoe Terakes (2000) Greek Australian - is trans masc non-binary guy (they/he) - has spoken up for Palestine!

D’Pharaoh Woon-A-Tai (2001) Ojibwe, Cree, Chinese Guyanese, Afro Guyanese, White.

Here you go! If you /tagged/NAME search on my blog you'll find gif packs with the vibes and please let me know if you need more preferably with a specific age rage!

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Follow the source link to 116 gifs of Viveik Kalra in the movie Three Months (2022). Viveik Kalra (born 1998) is a British actor of Punjabi Indian descent, known for his breakthrough role in the coming of age film Blinded By the Light. These gifs were made from scratch, please don’t claim them as your own. Trigger warning: kissing

#gif hunt#viveik kalra#viveik kalra gif hunt#poc gif hunt#my gifs#three months#three months movie#gif pack#south asian fc#lgbtq movie

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

a) Indentitas film

• Judul film: Kuntilanak 3

• Gender: Horor

• Sutradara: Rizal Mantovani

• Produser: Raam Punjabi

• Durasi: 105 Menit

• Perusahaan Produksi: MVP Pictures

• Penulis: Alim Sudio

• Pemeran: Nicole Rossi sebagai Dinda

Adryan Bima sebagai Kresna

Ali Fikry sebagai Miko

Adlu Fahrezi sebagai panji

Ciara Brosnan sebagai Ambar

Sara Wijayanto sebagai Sri Sukma Rahimi Mangkoedjiwo (Eyang Sukma)

Nafa Urbach sebagai Adela

Aming sebagai Bejo

Wafda Saifan sebagai Baskara

Nena Rosier sebagai Dona Wilhemina

Romaria Simbolon sebagai Mala

Clarice Cutie sebagai Uchie

Irish Ise sebagai Stefani

Emmie lemu sebagai Bonang

• Tanngal rilis: 30 April 2022

b) Sinopsis

Dinda yang dianggap aneh oleh anak-anak kampung karena kekuatannya,tidak sengaja melukai Panji,dan Ambar.Ia menemukan sekolah Mata Hati yang menampung anak anak dengan kemampuan khusus.Ia pun akhirnya bersekolah disana,berteman dengan anak anak yang memiliki kemampuan supranatural lainnya.Sayangnya,Dinda tidak mengira bahwa istri dari pemilik sekolah itu ternyata adalah seorang yang bersekutu dengan kuntilanak supaya dapat hidup abadi.Dia menyerap sukmanya dari anak anak yang bersekolah disana untuk menyambung hidupnya selama satu tahun.Dinda yang ternyata keturunan Mangkujiwo adalah sosok yang dicari karena sukmanya dapat membuat sang pemilik sekolah itu dapat hidup hingga delapan tahun lamanya.Pada saat itu saudara dinda,Miko dan kresna menyelidiki sekolah mata hati itu dan menemukan hal hal aneh seperti banyak murid yang menghilang.Miko dan Kresna tidak mau dinda merasakan hal itu mereka pun berinisiatif untuk pergi ke skeloah itu dengan menyamar menjadi murid disekolah tanpa adanya kekuatan.

c) Kekurangannya Film ini kurang horor untuk kategori film horor,karena pada akhirnya ada beberapa kesimpulan yang bisa dirangkumnya.Jika film ini di niatkan sebagai film horor fantasi,maka sentuhan fantasinya menutup kesan horor yang mungkin diidamkan bagi penonton.Jika bila film ini diniatkan sebagai film yang fantasinya lebih dominan maka film ini bisa dibilang berhasil.

d) Kelebihannya Film kuntilanak 3 ini sepertinya membuka cerita baru.Film ini berfokus pada Kuntilanak yang menuntut balas sekaligus bersemangat menyerap sukma Dinda yang disebut sebagai jagal Kuntilanak.Setiap tokoh dalam film ini punya karakter yang kuat.Lima anak yang menjadi peran utama mereka masing masing punya porsinya sendiri untuk menjalankan cerita.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sanjay Balraj Dutt (born 29 July 1959) is an Indian actor who works in Hindi cinema in addition to a few Kannada, Tamil, Punjabi and Telugu films. In a career spanning over four decades, Dutt has won several accolades and acted in over 135 films, ranging from romance to comedy genres, though usually in action genres, thus proving himself one of the most popular Hindi film actors since the 1980s.Dutt gained widespread acclaim for playing Munna Bhai in Rajkumar Hirani's Munna Bhai series (2003–2006), his most iconic role, and his biggest sole commercial success ever. Since 2000, his other notable films include - Jodi No.1 (2001), Parineeta , Dus (both 2005), Shootout at Lokhandwala , Dhamaal (both 2007), All the Best (2009), Double Dhamaal (2011), Agneepath, and Son of Sardaar (both 2012). He reunited with Hirani on PK (2014). This was followed by another major career downturn with the exceptions of Kannada film K.G.F: Chapter 2 (2022) and the Tamil film Leo (2023), the former being the 4th highest-grossing Indian film and the latter being the 12th highest-grossing Indian film, both in which he played the main antagonist.

0 notes

Text

Top Punjabi Male Actor

Kirandeep Rayat is one of the youngest and most famous actors in the Punjabi film industry. He has been a model and made his debut in the Punjabi cinema with “Jindra” in 2022 where he played the role of Jassa Singh.

Kirandeep Rayat is one of the talented and most handsome actors of Punjab. He has earned great fame and name due to his excellent acting skill and charming nature in the movies. He has gained a huge fan base on social media due to his bold and smart personality.

#punjabi#punjabi songs#punjabi movies#latest punjabi songs#latest punjabi movies#new punjabi movie#latest punjabi movie#new punjabi song#new punjabi songs#punjabi movie#punjabi movie 2022#punjabi comedy#punjabi actors#new punjabi movie 2022#punjabi film 2022#latest punjabi movie 2022#latest punjabi movies 2022#ptc punjabi#punjabi song#punjabi action movie#punjab#punjabi singers#punjabi song 2021#latest punjabi film#faraar punjabi song

0 notes

Video

youtube

Song: Mundri

Movie: Teri Meri Gal Ban Gayi (2022) [Punjabi]

Starring: Priti Sapru, Guggu Gill,

Music Composer : Jatinder Shah, Lyrics: Babu Singh Maan

Singers: Master Saleem & Gulrez Akhtar

-- Mundri | Teri Meri Gal Ban Gayi | Akhil | Rubina | Master Saleem| Gulrez A| Priti Sapru| Jatinder S (via Times Music)

0 notes

Text

Respect 2021 | Movie Trailers

Respect 2021 | Movie Trailers

Following the rise of Aretha Franklin’s career — from a child singing in her father’s church choir to her international superstardom — it’s the remarkable true story of the music icon’s journey to find her voice.

Release date: 13 August 2021 (USA)

Director: Liesl Tommy

Screenplay: Tracey Scott Wilson

Production companies: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Bron Studios, Creative Wealth Media Finance,…

View On WordPress

#2022 Movie Trailers#Film Trailer#ign movie trailer#Latest Movie Trailer#movie#movie trailer#Movie Trailers#movie trailers 2021#movie trailers 2022#movies#new movie trailer 2022#new movie trailers#new movie trailers 2022#new trailer 2022#new trailers#official trailer#PISTOL Trailer#pr movie trailer#punjabi movie trailer#ranbir singh new movie trailer#ranveer singh new movie trailer#The Best Upcoming Movies 2022#trailer#trailer 2022#trailers

0 notes

Text

Mississippi Masala: The Ocean of Comings and Goings

By Bilal Qureshi

MAY 25, 2022

often remark that my Punjabi parents immigrated to the American South woefully unaware that they’d brought us to a place with an incurable preexisting condition. Racism doesn’t belong exclusively to the South—the former Confederacy—but it was implemented at industrial scale across the region’s economic, political, and cultural life. Alongside this landscape’s sublime natural beauty—rivers, fields, and bayous—sits the history of America’s unsparing brutality against its Black citizens. On the other side of the world, in South Asia, as well as among its global diasporas, anti-Blackness is embedded in ideas of colorism and caste, in tribal imaginaries and policed lines of “suitable” marriages.

The possibility to live—and to love—across racial borders is the theme of Mira Nair’s extraordinarily prescient and sexy second feature film, Mississippi Masala (1991). Three decades later, it speaks to a new generation as groundbreaking filmic heritage—but also with an almost eerie, prophetic wisdom for how to live beyond the confinements of identity and color. Even by today’s standards, the film is a radical triumph of cinematic representation, centering as it does Black and Brown filmmaking, acting, and storytelling. It is also a genre-defying outlier that would likely be as difficult to get financed and produced today as it was then. Part comedy, part drama, rooted in memoir and colonial history, the film that Nair imagined was a low-budget independent one with global settings and ambitions. The notion of representation—perhaps more accurately described as a correction of earlier misrepresentations—wasn’t its point or its currency. Race was its very subject. Nair has said she wanted to confront the “hierarchy of color” in America, India, and East Africa with the film—the kinds of limitations that she had experienced firsthand by living, studying (first sociology, then film), and making documentaries in both India and the United States. In a shift that began with her first feature film, Salaam Bombay! (1988), Nair set out to transform those real-world issues into fictionalized worlds, translating her sociological observations into works suffused with beauty, music, and, in the case of Mississippi Masala, humid sensuality.

Nair first engaged with the questions at the heart of the film when she came to the United States from India to study at Harvard in the mid-1970s. As a new arrival to the country’s color line, she has recalled, both its Black and white communities were accessible to her, and yet she belonged to neither. The experience of being outside that specific American binary would be a formative and fertile site of dislocation for the young filmmaker. Nair trained in documentary under the mentorship of D. A. Pennebaker, among others, and her first films were immersive explorations of questions that haunted her own life. The pangs of exile and homesickness for lost motherlands became the foundation of So Far from India (1983), and the boundaries of “respectability” for women in Indian society the subject of India Cabaret (1985). Salaam Bombay!—made in collaboration with her fellow Indian-born classmate, the photographer and screenwriter Sooni Taraporevala—carried her Direct Cinema training to extraordinary new heights. Working, from a script by Taraporevala, with nonactors on location in the streets of Mumbai, Nair found a filmic language that could merge the rigor of realism with the haunting emotion of fiction. It would become the creative model for Nair and Taraporevala’s translation of the real-life phenomenon of Indian-owned motels in the American South into a spicy cinematic blend of migration, rebellion, and romance.

During research trips across Mississippi, Louisiana, and South Carolina that Nair made in 1989, she discovered that many of the Indian motel owners in the South had come to the United States from Uganda following their expulsion by President Idi Amin in 1972. Ten years after the East African country gained its independence from British rule, Amin had blamed his country’s economic woes on its privileged and financially successful South Asian community. In the racial politics of empire, the British had privileged the Indian workers they had imported to East Africa, creating racial hierarchies Amin now wanted to destroy by way of politicizing race anew. In a line that is repeated in the screenplay, the mission was “Africa for Africans,” and for tens of thousands of Asian families, it was an uprooting and dislocation from which some would never recover.

In Mississippi Masala, the classically trained British Indian actor Roshan Seth plays Jay, the immigrant father who is the focal point of the “past” of the film’s dual narrative, which is beautifully balanced in the way that it interweaves the perspectives of two generations. In the film’s harrowing overture, Jay—along with his wife, Kinnu (Sharmila Tagore), and their daughter, Mina (Sarita Choudhury)—is being forced to flee Kampala, and he laments that it will always be the only home he has known. With stoic reserve, holding back tears, Seth conveys the gravity of the loss, as the camera captures the lush beauty of the family’s garden and the faces of those they must leave behind. Throughout the film, as Kinnu, Tagore—an acclaimed Indian film star and frequent Satyajit Ray collaborator—is a composed counterpoint to Seth’s troubled Jay in her character’s strength and resilience. When the film picks up with the family two decades later, Kinnu is shown managing the family’s liquor store, while an aging Jay writes to petition Uganda’s new government to reclaim his lost property. Nair’s camera pans up from his writing desk to reveal through his window the parking lot of a roadside Mississippi motel. This is where Jay works and exists in a permanent state of nostalgia, until he is jolted awake by Mina’s demands for a home and a life of her own.

Even as Jay dreams in sepia-toned memories, the film itself never descends into saccharine longing or scored sentimentality. The rigor of the research and on-location filmmaking in both Mississippi and Kampala is reflected in an unvarnished and immersive visual style. While Nair herself clearly understood the fabric of the lives of the Gujarati Hindu families she was portraying, she has discussed how Denzel Washington became a critical collaborator in ensuring that southern Black life was rendered with equal attention to detail, cultural specificity, and dignity. The result is a film whose homes and communities are etched with a palpable sense of reality.

All of Mississippi Masala’s disparate threads are bound together by a distinctly sultry southern love story, which naturally remains the best-remembered feature of the film. The meet-cute of Mina and Washington’s character, Demetrius, is quite literally a traffic collision, a not-so-subtle suggestion that, without a bit of movie magic and melodrama, these two southerners might never have been maneuvered into the exchanged numbers and glances, and palpable wanting, that still burn the screen today. The film is fueled by the gorgeousness and megawatt charisma of both its stars, the young Washington paired with Choudhury in a prodigious debut as a woman at the edge of adulthood—her mane of wavy hair, their sweaty night of dancing to Keith Sweat, aimless late-night phone calls, dark skin in white bedsheets, secret meetings, consummated desires.

In the background of the R&B song of young, electric love are the film’s quieter, deeper notes on migration. A string leitmotif by the classical Indian violinist L. Subramaniam recurs whenever the vistas of Lake Victoria across the family’s lost garden in Kampala appear on-screen in brief flashbacks. Nair’s mastery with music has only deepened with time, resulting in films that integrate archival and original music with a free-form alertness that is distinctly her own. Both for the African American people living amid strip malls in the dilapidated neighborhoods of a region to which their ancestors were brought by bondage, and for the Indian families forced by Amin to flee their homes, exile is expressed in stereo. As Jay pines for the country he lost, Demetrius’s brother dreams of visiting Africa and saluting Nelson Mandela—disparate but recognizable longings and family histories shared over a southern barbecue, American bridges.

There wouldn’t be racial borders, however, if they weren’t policed, and the policing authorities here come from across the racial spectrum. When Mina and Demetrius’s relationship is discovered by nosy Indian uncles, those boundaries flare up. From the Black ex-girlfriend who asks why the good Black men can’t date Black women, to the Indian uncles who barge into Demetrius and Mina’s hotel room, to the gossiping aunties who during phone calls mock Mina’s rebellious scandal, there is a veritable chorus of condemnation. It is portrayed with great comedic timing and wit, including from Nair herself, who delivers some of the sharpest lines of disapproval in the role of “Gossip 1.” But the implications of those judgments remain unfunny by design. The film’s remarkable achievement is the way it never buckles under the thematic weight of these uncomfortable truths. Nair always delivers her cerebral punches with a lightness and warmth that are precisely calibrated. These are the markers of a filmmaker in full control of the tone, color, production design, and, always, music to accompany the emotional demands of her material, and that facility has only gotten sharper in such masterpieces as Monsoon Wedding (2001).

Mississippi Masala showed at festivals in late 1991 and was released commercially in American cinemas in February 1992, within weeks of Wayne’s World and Basic Instinct. Working outside Hollywood’s conventions, Nair joined an extraordinary flowering in independent filmmaking that continues to be celebrated. The year 1991 had been a landmark one for Black cinema already, with the release of Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust, Mario Van Peebles’s New Jack City, and John Singleton’s Boyz n the Hood. Spike Lee’s opus Malcolm X, with Washington in the title role, would be released in the U.S. in late 1992. Nair’s film was shown at the same 1992 Sundance Film Festival at which a landmark panel about LGBTQ representation heralded a movement, named New Queer Cinema by moderator B. Ruby Rich, devoted to reclaiming stories of love and suffering from Hollywood’s gaze. These were parallel currents that echoed larger shifts and openings happening in global culture. The collapse of the Soviet Union, the end of apartheid in South Africa, India’s economic liberalization, and the rise of a youthful southern Democrat in the U.S. following a decade of Republican rule were stirrings of a new order. The possibilities were being felt all over the world as Nair’s film of southern futures arrived.

Described by the New York Times at the time as “sweetly pungent” and by the Washington Post as a “savory multiracial stew,” Mississippi Masala opened in American cinemas to rave, if exoticizing, reviews, less than a decade after Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi and Steven Spielberg’s portrayal of Indian characters eating monkey brains during a ritual dinner in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. Realistic international cinema featuring everyday South Asian life—as opposed to the Indian musical tradition or Hollywood’s tropes about foreignness—had almost no precedents or peers at the time. The depiction of South Asian characters as ordinary working-class Americans navigating questions of family, money, and love remains a radical achievement. Mississippi Masala also manages to decenter whiteness altogether. In a film about racial hierarchies, white characters appear only in the background, as the motel guests, patrons, and shopkeepers of Greenwood society. By design, this is first and foremost a film about Mina and Demetrius, and the families and communities that formed them.

Despite all the extraordinary accomplishments in the streaming age by the current generation of filmmakers of color, Mississippi Masala’s layered portrayal of race and love still feels unparalleled. To hear its characters speak candidly about the real lines that divide them, and reflect on the costs of crossing those lines, is to recognize the rigorous thinking—and living—that informed the screenplay. Even more disappointing than the lack of contemporary equals to the film, perhaps, are the offscreen parallels in South Asian communities like my own, where colorism and anti-Blackness are stubborn traditions yet to be fully dismantled. Stories of interracial love are still rarely told on-screen, and these relationships—the masala mixes—are still not visible enough to become as normalized as they deserve to be.

One of Nair’s first films, So Far from India, was filmed between New York City and Gujarat. It opens with a folk musician in the streets of Ahmedabad, a sequence that serves as a prelude to the film, about an Indian immigrant and the wife he has left behind. Nair, as narrator, translates his singing about the ocean of comings and goings. With Mississippi Masala, Nair positioned herself as both a great chronicler and a great navigator of that vast ocean of comings and goings. America is one of Nair’s homes, and she has made several films about the immigrant experience there, including her adaptations of Jhumpa Lahiri’s The Namesake (2006) and Mohsin Hamid’s The Reluctant Fundamentalist (2012). Each has sought to look at the country through the eyes of those usually on the margins in order to dramatize and problematize the idea of the American dream. It is these poetic and cinematic ruminations on identities in flux that feel like her most enduring, almost personal, gifts to hyphenated viewers like myself.

When I was younger, I thought Mississippi Masala embodied Mina’s rebellion, the promise of independence, and the freedom to choose whom and how to love. But now, twenty years after I first saw the film, at university, Jay’s longing for home and his incurable displacement feel equally, achingly resonant. With the limitations of America laid bare by the gift of adulthood, migration is no longer only a hurtling forward toward the rush of freedoms; it is now also the unknowable costs borne by my parents, the homes and selves they left behind.

The film’s closing credits, braiding Jay’s return to Kampala with glimpses of Mina and Demetrius kissing in the warmth of the southern sun, capture Nair’s exquisite feat of balancing—and blending—in Mississippi Masala. For a film traversing so many geographies and registers, there is finally a seamless harmony between father and daughter, between tradition and future, between here and there. As seen anew in restored colors, Mississippi Masala endures not for its spicy and pungent aromas of cultural specificity or representational breakthrough but for this profound commitment to multiplicity. It is a timeless song for and to those who live—and love—in multitudes.

#Criterion Collection#Mississippi Masala#Mira Nair#Charles S. Dutton#Denzel Washington#Roshan Seth#Sarita Choudhury#Sharmila Tagore#Joe Seneca#Bilal Qureshi

0 notes

Text

Ma Da Ladla Punjabi Movie//Indion Punjabi

Ma Da Ladla Punjabi Movie//Indion Punjabi

Ma ak ladla is indion punjabi movie which nisn full comedy movie entertainment is found in this movie it is full enjoyment movie maa ka ladla indion punjabi movie

Da Ladla is an Indian Punjabi parody movie coordinated by Uday Pratap Singh. The film was at first delivered on 16 September 2022 in India and USA.[1][2]

Read more

#Ma Da Ladla Punjabi Movie#Indion Punjabi#project moon#https://danishentertain.blogspot.com/2024/01/blog-post_698.html

0 notes

Text

15 febbraio … ricordiamo …

15 febbraio … ricordiamo …

#semprevivineiricordi #nomidaricordare #personaggiimportanti #perfettamentechic

2023: Raquel Welch, è stata un’attrice e modella statunitense. (n. 1940)

2023: Dario Penne, attore, doppiatore e direttore del doppiaggio italiano. Come attore prese parte ad alcuni film, ma fu soprattutto attivo in televisione. Penne è deceduto due giorni prima del suo 85º compleanno. (n.1938)

2022: Deep Sidhu, Sandeep Singh Sidhu, attore cinematografico indiano. Ha lavorato in film punjabi,…

View On WordPress

#15 febbraio#Alberto Schiappadori#Antonio Garrido Monteagudo#Antonio Moreno#Charles Bennett#Charles John Holt III#Dario Penne#Deep Sidhu#Dorian Gray#Enzo Consoli#Ethel Agnes Zimmermann#Ethel Merman#George Gaynes#George Jongejans#Harry Todd#Heinrich von Kleinbach#Henry Brandon#Ilka Chase#Isarco Ravaioli#John Nelson Todd#Larry Steers#Lawrence Wells Steers#Maria Luisa Mangini#Minnie Maddern Fiske#Morti 15 febbraio#Morti oggi#Mrs. Fiske#Nat King Cole#nata Marie Augusta Davey#Nathaniel Adams Coles

0 notes

Text

Box Office 2023: Punjabi films grossed Rs. 235 crores, Marathi films grossed Rs. 201 crores, Bengali films grossed Rs. 66 crores in 2023

Of late, Bollywood Hungama has reported on the box-office performance of Bollywood, Hollywood, Tamil, Telugu, and Kannada cinema in 2023. In this article, we shall discuss the box-office figures of Punjabi, Marathi and Bengali films in the domestic market.

Punjabi films had a historic 2019 as collections went up to Rs. 249 crores, the highest ever. In 2020, the figure was a mere Rs. 19 crores while it was Rs. 91 crores in 2021. 2022 was a bit disappointing as the total collections were Rs. 147 crores.

2023 figures were the second best of all time as it jumped to Rs. 235 crores. It is lesser than the 2019 numbers but the signs of improvement are there. The footfalls also grew from 1.50 crores in 2022 to 2.3 crores in 2023, which is almost at par with 2017 levels (2.3 crores). The biggest hit of the year, Carry On Jatta 3, was also the biggest Punjabi hit ever, collecting Rs. 54 crores gross. This was followed by Mastaney (Rs. 33 crores) and Kali Jotta (Rs. 21 crores).

The Marathi box-office performance, meanwhile, was underwhelming. It went on a record high of Rs. 268 crores in 2022. But the figure reduced to Rs. 201 crores in 2023. Footfalls are also down from 2.60 crores in 2022 to 2 crores in 2023.

2023 saw Marathi cinema delivering Baipan Bhari Deva, which exceeded all expectations. Backed by Jio Studios, this woman-centric film collected Rs. 92 crores gross in cinemas. It is also the second-biggest Marathi grosser of all time. Sadly, this was the only major blockbuster of the year. The second biggest grosser, Subhedar, collected Rs. 18 cores. Jhimma 2 collected as much as the first part - Rs. 14 crores. It suffered from mixed word of mouth and if the reports were encouraging, it had the potential to cross the Rs. 20 crores mark. What's unfortunate is that a film like Vaalvi got all-round acclaim and yet, it didn't even cross the Rs. 10 crores mark.

The Bengali industry similarly saw a drop in collections - from Rs. 77 crores in 2022 to Rs. 66 crores in 2023. While the footfalls were 70 lakhs in 2022, it was 60 lakhs a year later. Chengiz, the Eid release which was also the first Bengali film to release in Hindi, was the biggest hit of 2023 followed by Raktabeej and Dawshom Awbotaar.

#Baipan Bhari Deva#Bengali#Box-Office#Carry on Jatta 3#Chengiz#Jhimma#Jio Studios#Kali Jotta#Marathi#Mastaney#Punjabi#Subhedar#Vaalvi#bollywood hungama

0 notes