#proletarianization

Text

Tech workers spent a whole generation conceiving of themselves as entrepreneurs who bargained, nerd-to-nerd, with other entrepreneurs who needed workers as much as workers needed paychecks.

These workers allowed themselves to be convinced that being “extremely hardcore” — that is, working body- and mind-ruining hours (without overtime pay) was a badge of honor.

They let themselves believe that their bosses gave them gourmet cafeteria food, “on-campus” fitness centers and daycare because they were valued workers — and not because this created the conditions where workers could be induced to put in longer hours without additional pay.

They conceived of themselves as ascetic monks, a priesthood that labored every hour God sent to bring digitization to the world. Meanwhile, their bosses’ wealth soared, even as their own working conditions deteriorated.

Tech workers may be prone to the same rationalization and self-deception as the rest of us, but (like the rest of us), they aren’t fools. Anything that can’t go on forever will eventually stop.

As conditions and prospects worsened, tech workers’ identities as workers emerged from a generation-long coma. They penned manifestos, walked off the job, and formed unions.

-The proletarianization of tech workers: If there is hope, it is in the proles

#eric flint#science fiction#tech workers#labor#unions#there is power in the union#sf#labor organizing#proletarianization

699 notes

·

View notes

Text

"For Wells is a petit bourgeois, and of all the products of capitalism, none is more unlovely than this class. Whoever does not escape from it is certainly damned. It is necessarily a class whose whole existence is based on a lie. Functionally it is exploited, but because it is allowed to share in some of the crumbs of exploitation that fall from the rich bourgeois table, it identifies itself with the bourgeois system on which, whether as bank manager, small shopkeeper or upper household servant, it seems to depend. It has only one value in life, that of bettering itself, of getting a step nearer the good bourgeois things so far above it. It has only one horror, that of falling from respectability into the proletarian abyss which, because it is so near, seems so much more dangerous. It is rootless, individualist, lonely, and perpetually facing, with its hackles up, an antagonistic world. It can never know the security of the rich bourgeoisie or the companionship of the worker. It can never rest on anything, for it is always struggling to better itself. It is the most deluded class, for it has not the cynicism of the worker with practical proof of bourgeois fictions, or the cynicism of the intelligent bourgeois who even while he maintains them for his own purposes sees through the illusions of religion, royalty, patriotism and capitalist ‘industry’ and ‘foresight’. It has no traditions of its own and it does not adopt those of the workers, which it hates, but those of the bourgeois, which are without virtue for it, since it did not help to create them. This world, described so well in Experiment in Autobiography, is like a terrible stagnant marsh, all mud and bitterness, and without even the saving grace of tragedy.

Everyone seeks to escape from this marsh. It is a world whose whole motive force is simply this, to escape from what it was born to, upwards, to be rich, secure, a boss. And the development of capitalism increases the depth of this world, makes wealth, security, and freedom more and more difficult, and thus adds to its horror. More and more the petty bourgeois expression is that of a face lined with petty, futile, bewildered discontent. Life with its perplexities and muddles seems to baffle and betray them at every turn. They are frustrated, beaten; things are too much for them. Almost all Wells’s characters from Kipps to Clissold are psychologically of this typical petit bourgeois frustrated class. They can never understand why everything is so puzzling, why man is so unreasonable, why life is so difficult, precisely because it is they who are so unreasonable. They are born of the irresponsibility and anachronism of capital expressed in its acutest form. And they do not understand this.

The ways of escape from the petit bourgeois world are many. One way is to shed one’s false bourgeois illusions and relapse into the proletarian hell one has always dreaded. Then one finds a life hard and laborious enough but with clear values, derived from the functional part one plays in society. The peculiarly dreadful flavour of petit bourgeois bitterness is gone, for now the social forces that produce unhappiness – unemployment, poverty and privation – come quite clearly from above, from outside, from an alien world. One encounters them as members of a class, as companions in misfortune, and this generates both the sympathy and the organisation that makes them easier to be sustained. ‘It’s the poor what helps the poor.’ The proletariat are called upon to hate, not each other but impersonal things like wars and slumps and booms, or classes outside themselves – the bosses, the rich.

It is the peculiar suffering of the petit bourgeoisie that they are called upon to hate each other. It is not impersonal things or outside classes that hurt them and inflict on them suffering and poverty, but it appears to be other members of their own class. It is the shopkeeper across the road, the rival small trader, the family next door, with whom they are actively competing. Every success of one petit bourgeois is a sword in another’s heart. Every failure of one’s own is the result of another’s activity. No companionship, or solidarity, is possible. One’s hatred extends from the workers below that abyss always waiting for one, to the successful petit bourgeois just above one whom one envies and hates.

The development of capitalism increases both trends, the solidarity of the workers and the dissension and bitterness of the petit bourgeoisie.

It is also possible to escape upwards. Many are called. All who do not sink into the proletariat strive upwards. Only a few are chosen. Only a few struggle into the ranks of the rich bourgeoisie. Wells was one of those few. The story of this sharp, fierce struggle and its ultimate success in terms of his bank passbook is recorded in Wells’s Autobiography.

Some try to escape into the world of art or pure thought. But this escape becomes increasingly difficult. Take the case of the artist in the young Wells’s position. A dominating interest in art will come to him perhaps as an interest in poetry, in the short story, in new novelist’s technique. Painful and unproductive at first, his study of his craft will also be uneconomic. It will not pay. But how is he to live? Is he to proletarianise himself? Is he to starve in a garret on poor relief? But starvation in a garret as an outcast despised member of the community will necessarily condition his whole outlook as an artist. He will write reacting with or against proletarianisation, or as an unsuccessful petty bourgeois, or as an enforced member of the lumpen-proletariat, and all society will seem compulsive, rotten and inimical to him. Moreover, art itself in that era, being the aggregate of art produced by these and their like antecedent conditions, will be more and more outcast, turned in on itself, non-functional, and subjective, it will be the sincere, decadent, anarchistic art of a Picasso or Joyce.

It was impossible for Wells, imbued with this burning desire, to escape from the petty bourgeois hell, to accept art as an avocation, a social rôle, and be driven in on himself as an outcast from bourgeois values. He could only accept it as a means to success and the best road to cash. His autobiography reveals the early stages of his struggles in the literary market to attain five-figure sales and a five-figure income."

- Christopher Caudwell, “H. G. Wells: A Study in Utopianism,” in Studies in a Dying Culture. First published posthumously by Bodley Head in 1938.

#christopher caudwell#communist party of great britain#h. g. wells#petit bourgeoisie#bourgeois culture#bourgeois society#literary criticism#marxism#marxist criticism#literary quote#capitalism#proletarianization#class society

1 note

·

View note

Text

Me if I got a medal for every time I got called a psyop:

#death to the usa#i fucking hate liberals#sorry sugar the anti-parliamentarism will continue until you get an actual proletarian party

946 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s so funny when liberals lecture communists about not knowing how anything works, that we need to grow up and face the real world etc, while publicly demonstrating that their political imagination is so deeply impoverished that they genuinely believe the only thing the leader of the most powerful country on the planet in all of human history can do is block a slightly more fascist guy from taking his place every four years

#one of the reasons I am a communist is because I believe in the wondrous power of a state in the hands of the working class! like it is#legitimately moving to learn about the transformative ways socialists use a proletarian state to direct a socialist society#what boer calls god-building and newton calls demiurgical. the state has a universe-building potential to it#and even setting aside socialist history the idea that the president of the US is unable to affect any local or state policy within his own#borders or foreign policy without is so baldly laughable it shouldn’t even be worth considering#except for the fact that so many people profess to genuinely believe that#whether they actually do is another story but christ alive man.

925 notes

·

View notes

Text

The dumb, mildly fetishist "traditional wife" blogs like making posts about husbands choosing their clothes.

Throughout much of human history, WOMEN chose their husband's clothes, not the other way around.

Why? Usually, the women had made the clothes right down to weaving and colouring the fabric. Men wore the clothes their wives and mothers made for them, sewed for then, or even bought for them. They did that, and made damn sure to be happy about it, or they wore nothing at all.

That's why matching family sets of traditional folk costumes are a thing.

Never forget; he's not a ~trad husband ~, he's a loser that thinks the fucking stepford wives is a viable 21st century economic model and an accurate portrayal of history.

#feminism#proletarian feminism#womens art#traditional dress#traditional clothing#history#antifascism#anti tradwife#historical revisionism

493 notes

·

View notes

Text

most anarchists don't outright say they want to abolish building codes (or organisations) - but, practically, when the question of enforcement comes down to it, it's a different story. building codes that are not enforced are not building codes, they're fun suggestions. if you are not ensuring that all, in this case wheelchair ramps, are up to code, you functionally do not have building codes. it's the same issue as with organisation - without a concept of democratic centralism, 'what if the organisation decides to do something that a small subset disagree with' generally receives no solution other than just 'those people just won't do what the organisation decides', which in practice means there does not exist an organisation at all, just a group of people who currently happen to all agree on something, and will disintegrate when they stop happening to agree. in practice there can be no actual collective action, no ensuring wide conformity to codes and programs, without some form of central authority to make reference to. 'just let the village's Ramp Inspecting enthusiast decide if it's fine' does not a building code make.

#this is again not even getting into the fact that this is an issue of governance and not the state#where the continued existence of class struggle would further require building code enforcement have a proletarian state character to it#for the duration of the period of socialist construction

581 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why procreation should be "a fact of nature" rather than a social, historically determined activity, invested by diverse interests and power relations, is a question Marx did not ask. Nor did he imagine that men and women might have different interests with respect to child-making, an activity which he treated as a gender-neutral, undifferentiated process.

In reality, so far are procreation and population changes from being automatic or "natural" that, in all phases of capitalist development, the state has had to resort to regulation and coercion to expand or reduce the work-force. This was especially true at the time of the capitalist take-off, when the muscles and bones of workers were the primary means of production. But even later — down to the present — the state has spared no efforts in its attempt to wrench from women's hands the control over reproduction, and to determine which children should be born, where, when, or in what numbers. Consequently, women have often been forced to procreate against their will, and have experienced an alienation from their bodies, their "labor," and even their children, deeper than that experienced by any other workers. No one can describe in fact the anguish and desperation suffered by a woman seeing her body turn against herself, as it must occur in the case of an unwanted pregnancy.

—Silvia Federici, "Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation".

#silvia federici#marxist feminism#feminism#marxism#radical feminism#radblr#patriarchy#women's liberation#proletarian feminism

651 notes

·

View notes

Note

Looking through some posts, I noticed in the past you were genuinely anti-kink like 4 years ago. If you don't mind my asking, what changed?

i straight up did not become a sentient being until like mid 2020i remember like three events from before that total

#ask#im joking . mostly. kind of#a much simpler version of this is that i became a marxist and embraced a proletarian and materialist morality and worldview

148 notes

·

View notes

Note

Quit the job that doesn't pay me a living wage

Achievement Unlocked

Know Your Worth

Ditch your shitty underpaid job

282 notes

·

View notes

Text

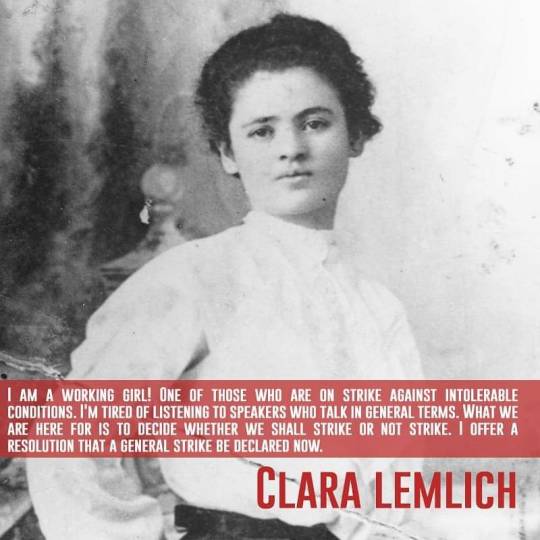

Lemlich was a Ukranian Jewish immigrant who emigrated to New York in 1903. She became a garment worker and joined the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union. She was a key leader in the Uprising of 20,000, the massive strike of New York garment workers in 1909. Blacklisted from the industry for her union work, she was active in the women’s suffrage movement. She joined was a leader of the United Council of Working Class Women. A life long activist, in her last years as a nursing home resident, Lemlich persuaded the nursing home to join in the United Farm Workers' boycotts of grapes and lettuce and helped the workers there to organize.

#jumblr#jewish#jews#nesyapost#jewish history#Ukrainian Jew#Jewish women#proletarian feminism#proletariat#immigrant history

169 notes

·

View notes

Text

Remember when tech workers dreamed of working for a big company for a few years, before striking out on their own to start their own company that would knock that tech giant over?

Then that dream shrank to: work for a giant for a few years, quit, do a fake startup, get acqui-hired by your old employer, as a complicated way of getting a bonus and a promotion.

Then the dream shrank further: work for a tech giant for your whole life, get free kombucha and massages on Wednesdays.

And now, the dream is over. All that’s left is: work for a tech giant until they fire your ass, like those 12,000 Googlers who got fired six months after a stock buyback that would have paid their salaries for the next 27 years.

We deserve better than this. We can get it.

-The proletarianization of tech workers: If there is hope, it is in the proles

#eric flint#science fiction#tech workers#labor#unions#there is power in the union#sf#labor organizing#proletarianization

253 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“By the mid-1830s, land policy, speculative endeavours and hoarding, and the penetration of the market and its solvent of social differentiation in town and country were lending considerable force to Goderich’s insistence that “there should be in every society a class of labourers as well as a class of Capitalists or Landowners.” This presaged Edward Gibbon Wakefield’s later enunciation, in 1833, of a theory of “systematic colonization,” which Marx integrated into his discussion of capitalist primitive accumulation.20 In the rural areas of the Home District, within which Toronto was located, some 10,172 out of 14,994 labouring-age males (68 per cent) were landless by mid-century, and wage rates had plummeted across the Canadian colonial landscape. With some 230,000 Irish immigrants crashing the Ontario-Quebec labour market in their flight from Old World famine in the later 1840s, the dispossession of this transatlantic proletarian contingent translated into a rural reserve army of labour, some of which inevitably found its way to Ontario’s cities.

Toronto inevitably confronted the fallout from this process of dispossession. Over the course of the winter of 1836–1837 an economic crisis exacerbated the growing problem: commerce stagnated; houses stood empty for want of rent; the Bank of Upper Canada pressured its debtors to settle accounts, including an ironworks that was forced to close, its 80 employees thrown out of work; a Mechanics’ Association was formed to lobby for the protection of the interests of tradesmen; and printers and tailors struck their masters. William Lyon Mackenzie, a newspaper editor and proprietor whose notoriety as a relentless critic of the aristocratic governing Tories and outspoken leader of the Reform element was well known, railed that his typographers should spend their evenings “studying the true principles of economy which govern the rule of wages.” Meanwhile, the flood of pauper emigrants passing through Toronto, estimated in the 1830s to be in the tens of thousands annually, continued, with fears of recent cholera epidemics associated with the immigrant ships fresh in the minds of many. A wageless, diseased population, increasingly visible on city streets and challenging its ruling order’s sense of public propriety and paternal responsibility necessitated a response. This was especially the case if firebrands like William Lyon Mackenzie were not to make ideological capital out of their constant harangues that social development and harmonious relations were threatened by a pernicious oligarchy, which was daily fomenting a “universal agitation.” Mackenzie’s obnoxious claims that “privilege and equal rights” and “law sanctioned, law fenced in privilege” were at loggerheads in Upper Canada in 1837, forcing a terrible contest, were but one reflection of dispossession’s distressing consequences.

At the centre of this history of dispossession was the 1830s creation of a set of carceral institutions which...criminalized the poor. Pivotal in this development, which extended beyond the Kingston Penitentiary and local and debtors’ gaols, was Toronto’s House of Industry. As conflicting historiographic interpretations of the meaning of the House of Industry suggest, it was, like almost everything in the city in 1837, contested terrain, pitting Tories against Reformers. The clash of oppositional forces around the establishment of the Toronto House of Industry played out in Radical Reformers such as Mackenzie and James Lesslie opposing the establishment of what they perceived to be an arm of the old-style English Poor Law discipline, long rejected in Upper Canada, at the same time that they embraced the need to extend relief of the poor. The practice of the Toronto House of Industry ironically ended up bringing some reformers and some members of the Family Compact together, bound as they were as men of property to a broad agency of class discipline. Impaled on the horns of class formation’s incomplete development in 1836–1837, both the clash of views around the House of Industry and the fate of the insurrectionary impulse of the Rebellion itself reflected a politics that was compromised and incompletely differentiated into oppositional interests. As Stanley Ryerson long ago noted, the proletariat, waged and wageless, was “not yet in a position to act in [its] own name or give independent leadership to the struggle.”

Something less punitive than was perhaps envisioned by crusading former English Poor Law Commissioner and recently-ensconced Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada, Sir Francis Bond Head, the Toronto House of Industry was nonetheless a decisive articulation that new initiatives had to be undertaken to address the poverty, disease, and wagelessness that engulfed Toronto. The Bond Head-endorsed 1837 statute, authorizing Houses of Industry to be erected across Upper Canada, produced little immediately. No such establishments, which at first were to be funded entirely by voluntary subscriptions, were set up outside of Toronto until the late 1840s. Nonetheless, the criminalization and institutionalization of the wageless reflected both the growing unease among the patrician and propertied, as well as their panicked recourse to discipline the unruly:

That the persons who shall be liable to be sent into, employed and governed in the said House, to be erected in pursuance of this Act, are all Poor and Indigent Persons, who are incapable of supporting themselves; all persons able of body to work and without any means of maintaining themselves, who refuse or neglect so to do; all persons living a lewd dissolute vagrant life, or exercising no ordinary calling, or lawful business, sufficient to gain or procure an honest living; all such as spend their time and property in Public Houses, to the neglect of lawful calling.…

… That all and every person committed to such House, if fit and able, shall be kept diligently employed in labour, during his or her continuance there; and in case the person so committed or continued shall be idle and not perform such reasonable task or labour as shall be assigned, or shall be stubborn, disobedient or disorderly, he, she or they, shall be punished according to the Rules and Regulations made or be made, for ruling, governing and punishing persons there committed.

“The chief objects,” of Toronto’s House of Industry, wrote one commentator supporting its creation in 1836, were “the total abolition of street begging, the putting down of wandering vagrants, and securing an asylum at the least possible expence for the industrious and distressed poor.” Toronto’s Poor House, as it was colloquially known, fittingly took over an old, abandoned building that had previously served as York’s Court House. At first the House was used primarily by widows, deserted women, and their children, and few receiving so-called indoor relief as inmates were actually male. Outdoor relief, or the dispensing of food and fuel to needy families, constituted most of the House of Industry’s work in providing for the poor. The first annual report of the House of Industry indicated that 46 persons received indoor relief, while the corresponding figure for recipients of outdoor relief was 857. In its earliest years two-thirds of those seeking aid from the new institution were Irish, demonstrating how poverty, criminalization, and ethnicity congealed.

In 1848 the House of Industry acquired a substantial new building. By the early 1850s, the refuge began taking in small numbers of homeless men, on average three a night, providing “an asylum to the indigent poor.” According to antiquarian histories, “many a homeless waif” received “a night’s lodging, with supper and breakfast, to invigorate him for the coming day’s search for work,” which was to be undertaken after male “lodgers” chopped some wood for the institution. These innovations and expanded assistance were implemented as temporary expedients, judged necessary as “the surest means of doing away with street begging.” It was understood that the “casual homeless” would have one night of shelter and then be on their way. From 1837 to 1854, Toronto’s refuge accommodated 2620 indigents, but its outdoor relief remained especially important. As Richard B. Splane suggested decades ago, the Toronto House was, in its beginnings both a house of refuge and a house of correction, a hybrid that could appeal to conservatives and liberals alike.

James Buchanan’s Project for the Formation of a Depot in Upper Canada with a View to Relieve the Whole Pauper Population of England (1834) envisioned a Foucauldian institution of inspection, monitoring, and training in religion, work discipline, and, for children, the rudiments of an education. This kind of response might be associated with high Toryism, congruent with its author’s claimed “hatred of Democracy,” but Buchanan had kinship connections with the leading family of moderate Reform, the Baldwins. Indeed, Dr. William Baldwin was to take up management of the Toronto House of Industry when it was established in March 1837. Thus the House of Industry proved a meeting ground of Tory and Reform on the eve of the Rebellion of 1837, foreshadowing the extent to which the political antagonists of this era might well share a common unease as the threatening portents of the dispossessed were increasingly obvious. Toronto’s wageless would exist in the shadow of the House of Industry for decades.

In the Era of Confederation: State Formation and the Poor

The Reform insurrection of 1837, however anti-climactic, dealt a series of death-blows to the ancien regime. In the subsequent era of state formation, culminating in Confederation in 1867, new senses of public responsibility and political culture consolidated in the 1840s. Mechanics and tradesmen petitioned legislatures in ways that would have been unimaginable in decades past, while local government was fundamentally reconfigured.36 Toronto’s 1846 Act of Incorporation was amended, widening the possible reach of control and coercion that could be deployed against the wageless by providing for the establishment of an industrial farm to complement the already existing House of Industry, which drew, from 1839 onwards, not only on private donations but on annual provincial grants. Over the course of the 1850s a spate of municipal legislation addressed the growing need to attend to the destitute and the workless; by 1866 the Municipal Institutions Act mandated that all townships in the province of Ontario with a population of over 20,000 provision houses of industry or refuge. Between 1840–1860, moreover, Toronto’s House of Industry competed with eight other local private charitable institutions receiving government grants for the relief of the poor. One crucial piece of legislation that followed on the heels of Confederation was the 1867 Prison and Asylum Inspection Act. It defined provincial responsibilities for social welfare and, of course, deepened the process whereby criminalization, incarceration, and relief of the indigent were not just associated as part of a common response to proletarianization, but were now bureaucratically congealed in a statute that assigned responsibility for these spheres of “correctional intervention” to a single inspector, John Woodward Langmuir.

Small wonder that the oscillating reciprocities of waged and wageless life instilled in those undergoing proletarianization a recurrent sense of grievance. A carpenter questioned the state of affairs in 1852: “He asks that it be fair, that for five months in the year able and willing mechanics, are compelled to accept the alternative of walking the streets or working for wages which do not afford ample remuneration for the labour performed.” Finally, “after submitting to all this, with apparent resignation – after enriching their employers by the sweat of their brow, on terms which barely keep the thread of life from snapping – they are told with barefaced effrontery that they were employed in charity.” Seasonal labour markets, with their harsh material ritual of winter’s idleness and paternalistic alms, were by mid-century being challenged by the dispossessed.

Economic crisis was the necessity that proved the mother of this new inventive stage in the developing responses to wagelessness, emanating not only from capital and the state, but from the proletarianized as well. The massive social dislocation occasioned by the arrival of tens of thousands of ill and impoverished famine Irish immigrants in the post-1847 years was one part of this process, helping to swell Toronto’s population to 45,000 by 1860–1861. At that point Toronto contained more people who were by birth Irish than those who were born in England, and the 12,441 Irish-born trailed only the 19,202 Canadian-born, many of whom likely had Irish parentage.40 So, too, with the emergence of the railroad and the advancing stages of industrial capitalist production in urban centres was class differentiation, organization, and conflict becoming more visible. The number of strikes in Canada soared in the 1850s, when 73 such work stoppages represented fully 55 per cent of all labour-capital conflicts taking place in the entire 1815–1859 period. No other decade saw more than 30 strikes. For the workless, however, it was the commercial collapse of 1857 that registered discontent most decisively.

The cruel impact of the economic downturn occasioned perhaps the first mass protests of the obviously organized unemployed in the Canadian colonies. Upwards of 3,000 Quebec City out-of-work labourers, many of them shipwrights and other workers employed in the building of vessels, convened St. Roch protest meetings, marched through the streets of Lower Town, and demanded work, not alms. Recognizing that their wageless plight was “the effect of ‘the crisis’ upon the shipbuilding interest,” the demonstrations of the workless, however moderate and often contradictory (rejecting alms they could also plead for bread and charitable relief from sources of government or private citizens), generated a mixed response on the part of the powerful. Newspapers could side with the demands of the workless, urging the colonial government to provide significant relief for the labouring poor, but as protests continued reporting took on a more critical tone, with headlines such as “More Mob Demonstrations.”

The crash of 1857 had a devastating effect on Toronto. Nineteenth-century commentators recorded the extent of the crisis, seizing the opportunity to moralize, conveying well the extent to which wagelessness was now associated with incorrigibility and criminality: “There was much suffering and want among the labouring classes, with a corresponding amount of drunkenness, vice, and crime.” Police records indicate that in 1857 one in nine Toronto residents faced arrest, finding themselves before the police magistrate. This state of affairs necessarily heightened class tensions. Jesse Edgar Middleton’s 1923 multi-volume official history of Toronto declared cryptically, “Much disorder was caused by railway construction laborers between 1852 and 1860.” Newspapers from the local Toronto Colonist to the distant New York Herald noted the profusion of beggars: “They dodge you round corners, they follow you into shops, they are found at the church steps, they are at the door of the theatre, they infest the entrance to every bank, they crouch in the lobby of the post office, they assail you in every street, knock at your private residence, walk into your place of business … .” Asserting that “begging has assumed the dignity of a craft,” the Colonist complained that, “Whole families sally forth, and have their appointed rounds; children are taught to dissemble, to tell a lying tale of misery and woe, and to beg or steal as occasion offers.” Correspondents bemoaned that Toronto’s “streets swarmed with mendicants” and that it was impossible to go into public thoroughfares without annoyance from them.

Over the course of the 1850s the House of Industry reported that the number of people seeking relief doubled, and the municipality upped its grant to the refuge by 100 per cent. Immigration agents attended to the newly arrived, providing bread, temporary shelter, passage money, and information relevant to settlement and employment. A House of Providence soon outstripped the Toronto House of Industry in terms of those it sheltered, with the annual collective days stay of the poor in the former totalling 45,722 compared to 27,863 for the latter in 1872. An Orphan’s Home, Boys and Girls Homes, and a Female Aid Society supplemented the charitable role of the House of Industry by the 1860s. But Toronto’s Poor House still received the largest provincial grant of any such institution in Ontario, its annual subsidy of $2900 amounting to 10.5 cents for each inmate’s daily stay. It also expanded its operations in the 1850s, opening a soup kitchen. With small towns and villages in Toronto’s hinterland urging their poor to seek relief at the House of Industry, it served an increasingly mobile contingent of the dispossessed, some of whom came, not only from across Ontario, but also from Europe and the United States. Bishop Strachan suggested, in 1857, that Toronto, with its “central position has become a sort of reservoir, and a place of refuge to the indigent from all parts of the Province.”

There was growing discontent among the small and concentrated bureaucratized, managerial officialdom that monitored the funding and activities of houses of industry and providence. Langmuir, for instance, disapproved of Toronto’s refuge even being called a “House of Industry.” No industry, he claimed, took place within its walls, the suggestion being that the poor should indeed be made to labour for their bed and breakfast. Such institutions were “Poor-houses and nothing but that.” Langmuir also suggested that absolute reliance on provincial funding was misplaced, since he believed it was well established that “every Municipality shall take care of its own poor.” He further regretted that a generalized permissiveness undermined the good an institutionalized response to poverty and wagelessness might accomplish, bemoaning the lack of more compulsory measures. Largely responsible for the Ontario Charity Aid Act of 1874, Langmuir elaborated a political economy of poor relief rooted in the belief that, “unless we desire to see local Poor Houses mainly supported by Government but entirely controlled by municipalities or private boards, the principle that further Government aid to such establishments should depend upon the amount they obtain from the general public, cannot be yielded.”

In the aftermath of the destabilizing consequences of the 1840s and 1850s, especially the crisis unleashed with the commercial crash of 1857, state formation in Canada culminated in what Langmuir would later describe as “one of the most complete charitable and correctional systems on the continent.” This was part and parcel of what Michael B. Katz, Michael J. Doucet, and Mark J. Stern have called “the social organization of early industrial capitalism.” The long recessionary downturn of 1873–1896, punctuated by acute crises in the 1870s and 1890s, however, taxed this system. As the wageless proliferated, those afflicted by it organized and resisted, their consciousness and activism challenging both the increasingly oppressive conditions imposed upon them by economic depression and the pressures towards compulsion that were inevitably at work in a relief order that could not accommodate the expanding numbers of indigent families and out-of-work labourers.”

- Bryan D. Palmer and Gaetan Heroux, “‘Cracking the Stone’: The Long History of Capitalist Crisis and Toronto’s Dispossessed, 1830–1930,” Labour/Le Travail, 69 (Spring 2012) 19-27.

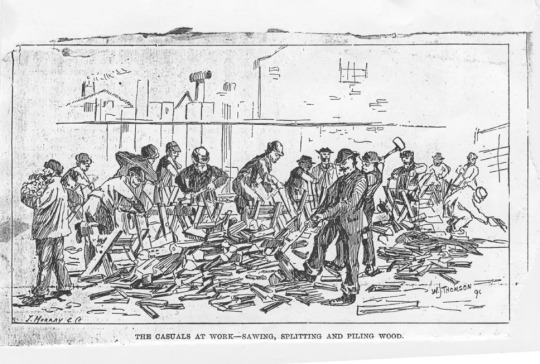

Image taken from the Toronto Star, showing relief recipients forced to labour for the city in the 1870s.

#toronto#toronto house of industry#unemployment#administration of poverty#proletarianization#wageless#house of industry#welfare as social control#pauperism#paupers#criminalizing vagrancy#vagrancy#problem of the poor#workhouses#geneology of liberalism#liberal era#canadian history#capitalism in canada#capitalism in crisis#academic research#nineteenth century canada#history of crime and punishment in canada

0 notes

Text

406 notes

·

View notes

Text

Folk instruments:

- accordion

- harmonica

- AK-47

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

I really need to get more into marxist god-building. As soon as I started reading a review of Lunacharsky’s writings on how Marxism evokes religious emotion and is basically scientific theology it was like discovering what i had believed but didn’t realise it

#also have been pretty compelled by his discussion of the role of religion in socialism#like in terms of capturing the ritual and social emotion that religion evokes for the purposes of uniting the working class#it resonated a lot with the history I’d read of the Haitian revolution and the role religion played in slave organising#like obviously religion plays a massive role in most conflicts but using it as a mobilising force for proletarian movements resolves a lot#of my confusion/uncertainty about religion in a socialist society#anyway I need to read a lot more I’m not very far into it#hoping maybe I can do a bit more reading in the summer but I have comp preparation then. augh#book club

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Women smiled more in pictures in the fifties as housewives"

Yeah! It was the legal prescription for meth to deal with the lack of marital rape laws!

67 notes

·

View notes