#postliberal theology

Text

* 하나님의 나그네 된 백성

저자 : 스탠리 하우어워스

- 스탠리 하우어워스(Stanley Hauerwas, 1940년 6월-)는 성공회 신학자이자 기독교 윤리학자이다. 사우스웨스턴 대학교를 나온 뒤 예일 대학교 신학대학원에서 신학과 윤리학을 공부해 석사, 박사 학위를 받았다. 노틀담 대학교를 거쳐 듀크 대학교 신학부에서 2013년까지 신학과 윤리학을 가르쳤다. 2000-1년에는 기포드 강연을 했으며 2014년에는 애버딘 대학교의 신학적 윤리학 교수가 되었다. 20세기 후반 대표적인 미국 신학자로 꼽히며 그리스도교 근본주의, 자유주의적 그리스도교에 모두 비판적인 노선에 서 있다. 이야기 신학(narrative theology)과 후기 자유주의신학(postliberal theology)의 영향 아래 기독교 평화주의, 공공 윤리, 정치신학, 철학적 신학 분야에서 다양한 저작을 남겼다.

- 스탠리 하우어워스는 전쟁을 비롯한 모든 폭력을 죄로 규정하여 반대하는 기독교 평화주의를 주장한다. 그 실례로 스탠리 하우어워스는 윌리엄 헨리 윌리몬 감리교 감독과 같이 쓴 《십계명》에서 기독교계에 기도를 부탁함으로써 진보적인 지식인들로부터 인도주의적 제국주의, 종교적 제국주의 전쟁이라는 비평을 받은 이라크 전쟁을 하느님의 뜻에 의한 전쟁이라는 종교적 논리로 정당화하려고 한 감리교도 조지 부시에 대해 하느님의 이름을 함부로 부르는 신성모독자라고 비판하였으며[3],이라크에 파병된 군인들을 위한 기도문을 작성함으로써 이라크 전쟁에 동조한 기독교 우파들에 대해서도 잘못된 전례(Liturgy)는 잘못된 윤리를 낳는다고 비판함으로써,미국 보수 기독교계의 폭력성과 부도덕함을 신랄하게 비판한다.

- "나는 기독교 신학자다. 사람들은 내가 그런 질문에 답할 수 있을 거라고 생각한다. 그러나 나는 그런 질문에 어떻게 대답해야 할지 모른다. (중략) 그러나 내가 볼 때, 그리스도인으로 사는 것은 답 없이 사는 법을 배우는 과정이다. 이렇게 사는 법을 배울 때 그리스도인으로 사는 것은 너무나 멋진 일이 된다. 신앙은 답을 모른 채 계속 나아가는 법을 배우는 일이다." (하나의 아이 375쪽)

—— 책 요약과 질문

1. 변한 세상

- 콘스탄틴누스식으로 교회와 세상을 하나로 묶었던 낡은 통합은 힘을 잃게 되었다.

Q: 변한 세상에서 더 이상 작동하지 않는 옛신학과 옛관습들은 어떤 것들이 있나?

Q: 변한 세상에서 그리스도인과 교회는 저항/타협/진보의 분별과 실천을 어떻게 해 나가야 하는가?

2. 올바른 신학적 질문들

- 설교자란, 고대의 낡은 세상인 성서와 새롭고 실제적인 세상인 현대 사이에 가로놓인 넓고 깊은 공백을 영웅적으로(예언자적으로) 연결하는 사람이다.

Q: 나는 어떤 설교자(메신저)인가? 어떤 설교자이고 싶은가?

3. 새로운 이해인가, 새로운 삶인가

- 바르게 산다는 것은 바르게 생각하는 것이라기보다는 도전하는 삶이라고 할 수 있다. 이 도전은 지적인 것이 아니라 정치적인 것이다. 즉, 그리스도로 말미암아 세상에 일어난 큰 변화에 동조해 사는 새 백성을 세우는 것이다.

Q: 정치적으로 도전하고 산다는 것은 무엇인가?

Q: 그리스도인과 교회는 세상의 정치적 과제에 어떤 메시지를 던져야 하는가?

4. 불신앙의 정치

- 세속적 휴머니즘에 맞서기 위해 공립학교에서 기도소리가 울려 펴져야 한다고 주장한다. 이런 식의 사고들은 콘스탄틴주의의 한 형태일 뿐이며, 역설적이게도 불신앙의 문화를 승인하는 것이다.

Q: 한국 기독교에서 발견할 수 있는 불신앙의 정치는 무엇인가?

Q: 그것들은 어디에서 비롯됐는가?

5. 사회 전략인 교회

- 나치 독일 때, 교회는 너무나 자발적으로 “세상에 봉사”했다. 나치즘 앞에 교회가 굴복한 것이다. 그러나 그때에 해야 할 일이 무엇인지는 정확히 몰랐어도, 최소한 참된 것을 말해야 한다는 소명을 품었던 사람들이 있다. 바로 고백교회였다.

(1) 행동주의 교회 - 교회 개혁 보다는 좀 더 나은 사회를 건설하는 일에 관심을 기울인다. 사회 구조를 인간화함으로써 하나님께 영광을 돌린다

(2) 회심주의 교회 - 개인 영혼에 초점을 맞추며, 오직 내적인 변화만을 위해 일하기 때문에 세상에게 나누어 줄 수 있는 자체의 사회 구조라든가 개인적인 사회 윤리를 가지고 있지 못하다.

(3) 고백교회 - 개인의 정신을 바꾸거나 사회를 변혁하는 데 있는 것이 아니라, 회중으로 하여금 만물 안에 계시는 그리스도를 예배하도록 결단케 하는 데 힘쓴다. 고백교회가 말하는 회심이란, 세례를 받아 새로운 백성, 즉 대안적인 폴리스이자 교회라 불리는 대항문화적인 사회 조직체에 접붙여지는 긴 과정을 의미한다.

Q: 우리 교회는 어떤 지향성을 가지고 있는가?

Q: 몰락해 가는 한국 교회의 회복을 위해 싸워야 할 것들은 무엇인가?

결론 : 성경은 일차적으로 한 백성이 하나님과 함께하는 여행에 관한 이야기이다. 성서는 하나님께서 들려주신 인간 실존에 관한 기록이다. 성경 속에서 우리는 하나님께서 우리 삶의 조각난 부분들을 모으시고 그것들을 하나로 묶어서 무엇인가 의미를 지니는 일관된 이야기로 만드시는 것을 본다. 흥미롭게도 초대 그리스도인들은 성육신의 형이상학에 관한 교리적 사변으로, 즉 복음서 기사에서 추론된 기독론으로 시작하지 않았다. 그들은 예수에 관한 이야기와 그의 삶에 매혹되어 살았던 사람들의 이야기로 시작했다. 그리하여 복음서 저자들은 그들이 몸소 실천한 삶의 모습을 기준으로 삼고 훨씬 더 복잡하고 매력적인 방식을 사용해 우리가 예수를 본받는 삶을 살아가도록 훈련할 수 있었다. 우리는 예수를 따르지 않고서는 그를 알 수 없다.

Q: 나는 성경을 어떻게 읽고 있는가?

Q: 성경읽기의 진보를 위해 필요한 것은 무엇인가?

Q: 나는 예수를 어떻게 따르고 있나?

0 notes

Quote

I write from a position of privilege. I am a white male, with a tenured position at an excellent academic institution in a wealthy and powerful nation. That privilege makes a difference to what follows. I am often deeply moved when Latin American theologians who risk getting murdered because of their work with the poor, or African American theologians, who have struggled all their lives against racism, write about their solidarity with the oppressed, but such language can ring false when I use it myself. I cannot pretend to be what I am not; I find myself struggling with the responsibilities of those who have worldy advantages rather than with the challenges of those without them. While the world's disadvantaged may often need to reflect first and foremost on how to empower themselves, I find myself thinking more about the dangers and ambiguities of power... Even those of us who live in privilege, if we take seriously the task of following Jesus Christ, may find ourselves called upon to make unexpected sacrifices, suddenly placed at risk among the despised and oppressed in surprising ways.

William Placher, Narrative of a Vulnerable God

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

First Things First: Uncle Reno’s Just So Stories

What do you get when you click on an article in First Things, that heady brew of theological harrumphing first set in motion by frenzied spiritual striver Richard John Neuhaus, about whom I (mostly) snickered here? Well, judging from this piece by the site’s editor, R.R. (Richard Russell) Reno, “End Times Anxiety”, you’ll learn a little, you’ll laugh a little, and you’ll conclude with a piece of sustained derision.

Surprisingly (or not), the Catholic Dr. Reno and I have a similar reaction to “Modern Times”, at least in part:

“Our present cultural moment is one of suspicion, anxiety, and worries about vulnerability. Many, perhaps most, fear that they are being discriminated against and marginalized. And those who don’t? They often live in the fear that they will be accused of white privilege or some other sin. Perhaps this is to be expected. Patriarchy, racism, heteronormativity—they are said to infect everything. One area of public discourse immune from the postmodern hermeneutics of suspicion is wonkish policy debate. But this is dominated by economistic thinking, which takes as its first premise rational self-interest. Here, too, we’re pictured as eyeing each other with competitive suspicion.

“The anxiety baffles me. Our society works pretty well. In many cities, crime is down dramatically, reaching historically low levels. The economy grows, both here at home and globally. American war-making has settled into a pattern of limited engagement that leaves most of us undisturbed. Meanwhile, public culture rings with warnings that things are heading toward disaster—global warming, resurgent racism, populism. Every week our office receives review copies of another book that promises to show us how to “save liberal democracy.”

Okay, I could do without the snicker about “postmodern hermeneutics” and the cutesy putdown of “rational self-interest”, but, hey, the guy’s Catholic. RR rumbles on a bit—well, more than a bit, actually—and then quotes to good effect someone I usually don’t care for much at all, Peggy Noonan, to wit:

“When at least half the country no longer trusts its political leaders, when people see the detached, cynical and uncaring refusal to handle such problems as illegal immigration, when those leaders commit a great nation to wars they blithely assume will be quickly won because we’re good and they’re bad and we’re the Jetsons and they’re the Flintstones, and while they were doing that they neglected to notice there was something hinky going on with the financial sector, something to do with mortgages, and then the courts decide to direct the culture, and the IRS abuses its power, and a bunch of nuns have to file a lawsuit because the government orders them to violate their conscience. . . .”

Well, again, I don’t think the IRS is abusing its power, and I don’t think the Little Sisters of the Poor should complain about being required to offer health care plans to their employees that provide free birth control pills,1 but the fact that Wall Street was rewarded for blowing up the economy,2 and that neither the Bush nor the Obama Administration had the nerve to walk away from a series of disastrous and counterproductive wars,3 not to mention occasional bloody acts of terrorism in the U.S. by isolated individuals (and not al Qaeda or ISIS or any other international terrorist group), are fundamental contributors to our national malaise.

I could go on in this vein for some time, but I already have, well, almost constantly for the past ten years, but my most recent “big picture” outburst, “Paging Dr. Yeats! Paging Dr. Yeats!, appeared only a couple of weeks ago, so I won’t belabor the point, except (and, okay, this is a pretty big “except”) it would be nice if Peggy, and maybe R.R. would admit that 1) the Republican Party started all these goddamn useless foreign wars and keeps looking for new ones (e.g., Ukraine, Syria, Iran, China) and 2) did their level best to not only prevent President Obama from countering the effects of the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression but actually sought to wreck the U.S. economy in the hopes of driving Obama from power.4

Well, enough of that. Suffice to say that the failure of the center has strengthened the extremes, and encouraged the notion that “truth” resides there. The more “passionate” you are, regardless of substance, the more valid. You can read either R.R. or myself on the fine points.

R.R. has something more satisfying to say, about which I’ll also carp, mourning the death of “the most significant influence on my intellectual life,” George Lindbeck (this article is my introduction to both men). Lindbeck was a Lutheran, who taught at Yale Divinity School and, according to Wikipedia, is one of the founders of “postliberal theology”, whatever that is. Wikipedia’s writeup highlights Lindbeck’s involvement in the movement and “explains” that many second-gen postliberal types, including R.R. himself, left the Protestant faith and joined the Catholic Church, quite in the manner (as Wikipedia also notes) of the Oxford “Tractarian Movement” in Victorian England.

R.R. tells us that “[Limbeck] was and remained a Lutheran, and he had only a small degree of sympathy for my conservative political leanings. But I can’t imagine thinking about theology the way I do without his example”:

“Lindbeck taught me this lesson [something about theology, obviously] when lecturing on an early medieval controversy between two monks, Radbertus and Ratramnus. Their dispute concerned whether or not the consecrated bread and wine is Christ’s physical body or his spiritual body. His patient unpacking of this controversy allowed me to understand his metaphor of “grammar.” Both monks wanted to affirm the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, the consensus affirmation for almost all Christians, not just in the twelfth century, but in our time as well. However, there is no consensus about what makes things real—a metaphysical question. As a consequence, it’s possible for someone to treat spiritual presence as more real than physical presence. Platonism encourages this way of thinking. The Pythagorean theorem is more “real” than any particular right-angle triangle. Others find this dissatisfying and emphasize the thatness of things, which is to say, their physical presence. This, moreover, is not just a matter of differing philosophical intuitions. The Bible suggests divergent metaphysical affirmations. The opening chapters of Genesis encourage a focus on physical presence, but Jesus’s statement that his kingdom is not of this world points toward the view that the spiritual is more real than things we can see and touch.”

Well, if you’re still with me, I just want to chuckle, amidst all this learnedness, about the line “Both monks wanted to affirm the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, the consensus affirmation for almost all Christians, not just in the twelfth century, but in our time as well.” That is so not true. The Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation, that the bread and wine become the body and blood of Christ, is rejected by the Lutheran doctrine of consubstantiation (both bread and body and wine and blood), the Eastern Orthodox notion of “mystery”, which explicitly and unsurprisingly rejects the Catholic doctrine (in his “twelfth century” reference, R.R. forgets, as so many Catholics do, the very existence of the Eastern Orthodox Church), the Anglican Church’s “whatever”, and the Calvinist rejection of any “magic” at all, part of the basic Protestant thrust to strip the priests of divine authority.5 And today, among the majority of American Protestants—the Evangelicals—the Eucharist plays no role in their faith whatsoever.

Furthermore, R.R. could have chosen, but of course did not, a topic that would prove more obviously divisive, such as the existence of Purgatory, which is rejected by all Protestants and the Eastern Orthodox, or, most divisive of all for Catholics and Lutherans—even more so the infallibility of the Pope when speaking on matters of faith—the question of free will versus predestination. What R.R.’s affection for Lindbeck signifies is the flocking together of all those who fancy metaphysical reveries, which, like the brook, can go on forever.

According to Wikipedia, Lindbeck and his fellow postliberal pals went back to Karl Barth, among others, for inspiration, which makes sense because Barth was one of the early twentieth-century enemies of “Whiggery”, ridiculing the idea that Christ was the first socialist (as Leopold Bloom called him). By my wildly casual reading, Barth took Kant’s categories, designed to secularize Protestant values, and reworked them to justify the metaphysical theology that Kant felt he had disassembled, naturally making it even more rigorous, and “postliberal/antiliberal” as he did so. Progress? Bah! Enlightenment? Nonsense!

Wikipedia informs me that the seminal event in Lindbeck’s career was serving as a guest observer at the famous/infamous “Vatican II” council,6 running from 1962 to 1965, which opened up for Lindbeck, one can be sure, whole new worlds (an infinite number, in fact) of metaphysical speculation. “Why can’t we have this?” he must have exclaimed.

Wikipedia further informs me that Lindbeck and his followers were heavily influenced by Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations, published posthumously in 1953 and written largely to reject the ideas expressed in the only work that Wittgenstein published in his lifetime, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus.7 The notion that one has to master Wittgenstein to get into heaven strikes me as a little strict and just a bit off point. Wittgenstein, though heavily influenced by Christianity personally, certainly never belonged to a church, and moreover always encouraged his students not to pursue a career in philosophy but rather to serve humanity via medicine. The point of philosophy, Wittgenstein thought, was to prove that the study of philosophy led nowhere—though of course that was all he ever thought about.

Wittgenstein’s thought strongly echoes the ideas expressed in Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason, which “explains” why all traditional metaphysics are false—because it applies concepts that effectively describe the finite world to “infinite” realms, where they are out of place. Unfortunately, finite concepts are the only ones we have. Wittgenstein’s favorite philosopher was Artur Schopenhauer, who saw himself as Kant’s disciple. Kant’s Religion Within the Limits of Reason Alone, a substantially simpler work than the “thorny” Critique, effectively explains, to my mind, why the theological hairsplitting that so engages both Lindbeck and Reno never ends. And why would they want it to, since they enjoy it so much? Of course, the larger doctrinal divisions between “confessions” are very largely the result of power struggles between entrenched groups, not spontaneous musings, which is why such groups always find ways to disagree with, not to mention burn, one another.

Yeah, this is a long post. Well, you’re here, aren’t you? After bidding farewell to his Lutheran mentor, R.R. throws a few random punches, at modernizing Catholics and free-market know nothings, before coming up with the riff that set me off in the first place, “explaining” how Ronald Reagan engineered morality by cutting taxes, thus encouraging hard work instead of dissipation:

“This was brought home to me decades ago when I was watching John Updike being interviewed on Book TV. He was asked what he thought of his early novels. The celebrated author adopted an amused look and allowed that they were to some degree dated. He recounted a recent trip to an elite university. The students told him that his stories, many of which revolve around afternoon martinis and sexual escapades, ring false. It was not as though life in upscale America had become more buttoned up in the interval between the publication of Rabbit, Run (1960) and their adolescent years in the 1990s. Rather, they told Updike, no adults were home in the early evenings, and their parents were too tired to throw the sorts of cocktail parties that provide the occasions for the alcohol-fueled transgressions that figure prominently in Updike’s fiction. As Updike told the interviewer, he had to inform these hard-charging, high-achieving kids that upper-middle-class grown-ups didn’t work so hard in the 1950s. People had more time on their hands.”

I could point out—and I will—that Rabbit, Run was not about upper-middle-class grown-ups. “Rabbit”, saddled with the ludicrously “loaded” last name of “Angstrom”,8 is a former high-school jock who sells a kitchen “gadget” called the “MagiPeeler” for a living. Updike wrote quite consciously, and conscientiously, about the middle class. Couples, his raunchy blockbuster, which came out in 1968, had more of a mixed group—everyone from a “contractor” to a nuclear physicist, but I think we’re hardly in Don Draper territory.9

More importantly, if we look at the actual data, instead of a novelist’s musings, we find, well, a mixed bag. According to *Measuring Leisure: The Allocation of Time Over Decades, published in 2006 by Mark Aguiar and Eric Hurst for the Federal Reserve Bank in Boston, hours worked by individuals with more than a high school degree declined from 1965 to 2003, from 52 to 43 hours per week. Another study, The Expanding Workweek? Understanding Trends in Long Work Hours Among U.S. Men, 1979-2004, by Peter Kuhn and Fernando Lozano for the National Bureau Of Economic Research, did find an increase, but dated the origin from 1970, 12 long years before Ronnie’s big cuts took effect.

Most importantly of all, wasn’t there a fair amount of hanky-panky going on in the eighties and nineties, alcohol-fueled or no? How about Donald Trump, hangin’ in Studio 54, aka “Cocaine Alley”, watching supermodels bangin’ n’ snortin’ in public? And what about soon to be chair of the president’s Council of Economic Advisors Larry Kudlow, who blew up his Wall Street career and his marriage via the White Lady back in 1995? And how about Wall Street “Wolf” Jordan Belfort, whose lifestyle was even more obscene than the hours he worked? Seems like this postliberal theology stuff might not be all it’s cracked to be. In fact, I wonder what either Barth or Wittgenstein might think of R.R.’s “logic”.

Afterwords

R.R.’s affectionate tribute to his mentor Lindberg suggests that genial companionship is more highly valued than mere “ideas”. Although both men surely took all their high-flying metaphysics seriously—believed they were necessary for salvation, which is pretty important after all—one can bet that neither ever tried to “convert” the other. How gauche can you be? If he could have done so, would Ross have journeyed to Lindberg’s deathbed, priest in tow, to save his friend’s soul? I think not. But wasn’t it his Christian duty to do so? Just sayin’.

Yeah, the gals don’t want to spend their money on birth control. But health care is “compensation”. Could the Little Sisters forbid their employees from using their wages to buy birth control pills? Then why should the employees be denied the opportunity to select a health care plan that offered them for “free”? ↩︎

The federal bailout was necessary, but in the past when the International Monetary Fund bailed out “bad” nations like South Korea they were required to “reform”. Far from requiring Wall Street to “reform”, the Obama Administration, led by Secretary of the Treasury Tim Geithner, rewarded them. Furthermore, while Wall Street bankers drank their own Kool-Aid during the Boom (making the same investments they advised their clients to make), when things were falling apart there was a great deal of criminal deceit, as might be expected. The Obama Administration swept this under the rug. “Do you want us to put everyone in jail?” ↩︎

The Bush Administration, of course, could hardly abandon its “Mission Accomplished” swagger without looking like losers. The possibility that the Obama Administration would pursue a policy of military withdrawal was destroyed by the rise of ISIS and Putin’s seizure of the Crimea. It is “arguable” (I know it is, because I’ve done it a lot) that Hillary Clinton’s aggressively anti-Russian policy in Eastern Europe, and her general contempt for Russian “interests”, led directly to the Ukrainian crisis that precipitated Putin’s decision to invade land that had been part of Russia for several centuries. ↩︎

After 9/11, the Democrats accepted the need for national unity and led President Bush set the national agenda, which he did with a clear eye towards partisan advantage. Under Obama, the Republicans furiously resisted every presidential proposal and were determined to undermine every possibility of economic recovery, because Obama. ↩︎

Voltaire, that shallow, shallow fellow, put it more succinctly: “The Catholics say they eat God, and no bread. The Lutherans say they eat God and bread. And the Calvinists say they eat bread and no God.” Luther invented the “theory” of consubstantiation because he had to be different from the Catholic Church, yet, having one foot still in the Catholic Church, couldn’t go “full Calvin”. Luther’s affection for the “traditional” Eucharist is “interesting” because he stripped away all other elements of priestly “magic” (holy relics, extreme unction, etc.). ↩︎

As Ross Douthat shrewdly observed, Vatican II was largely intended to make the Catholic faith palatable to the American establishment, which, the Vatican shrewdly reckoned, was the only force that could save them from communism. Among other things, Vatican II abolished the Index Librorum Prohibitorum, the “Index of Prohibited Books”, which had been updated as recently as 1948 and embarrassingly included such classics as Galileo (of course), Montesquieu (the “celebrated Montesquieu”, as the Founding Fathers always called him), and “even” Blaise Pascal (I guess for making fun of the Jesuits and for not renouncing the evil Cornelius Jansen). ↩︎

It’s a little shocking that Word can’t spell “tractatus”. I’ll bet that Bill Gates has read Wittgenstein. ↩︎

You can learn all about Angstroms here. It’s possible, I guess, that Updike met someone named “Angstrom” (it’s a Scandinavian surname as well as a unit of measurement equal to one ten-billionth of a meter) and therefore felt entitled to use it. ↩︎

I wrote an “homage” of sorts to Updike in my little book Author! Author! Auden, Oates, and Updike, though I doubt if he would appreciate “The Apotheosis of John Updike: A Modern Triptych”, which “he” narrates in the first person. ↩︎

0 notes

Quote

When I teach theology classes, I often start with an exercise about various levels of theological disagreement.

1). "This theological view is not mine, but I'm glad it's on the landscape to add variety and to challenge me." - For me this includes process theology, narrative/postliberal theologies, etc.

2). "This theological view is not mine, but it's harmless enough that I'm willing to let it slide without challenge." - Non-Chalcedonian Orthodoxy fits this slot for me.

3). "This theological view is not mine, and it's problematic enough to where I'm going to devote my efforts to providing a better alternative in my own work." - Denials of the Trinity are here for me, as is biblical literalism.

4). "This theological view is so problematic that I think that it's bad for humanity that anyone holds it, and adherents should be actively discouraged from believing it." - Theologies that view the earth as ultimately disposable to God's plan of redemption are here for me, and of course any hate-based theology such as Westboro Baptist.

I then ask them to provide an example of a theological statement (not a school or formal notion, unless they know some already) that fits into each category for them.

It's a helpful exercise.

Robert Saler

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Evangelicals Can Learn From George Lindbeck by Mark Alan Bowald

What Evangelicals Can Learn From George Lindbeck by Mark Alan Bowald

Image processed by CodeCarvings Piczard ### FREE Community Edition ### on 2018-02-05 16:34:53Z | http://piczard.com | http://codecarvings.com George Lindbeck, longtime professor of historical theology at Yale Divinity School, passed away on January 8. In evangelical circles he is best known as the author of The Nature of Doctrine: Religion and Theology in a Postliberal Age (Westminster Press,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

What Evangelicals Can Learn from George Lindbeck

Here's why one of the leaders of postliberalism thought evangelicals would carry the torch.

George Lindbeck, longtime professor of historical theology at Yale Divinity School, passed away on January 8. In evangelical circles he is best known as the author of The Nature of Doctrine: Religion and Theology in a Postliberal Age (Westminster Press, 1984) and as one of the two founding fathers of postliberal thought, the other being Hans Frei.

One important point of clarification is warranted at the outset. There remains a lot of uncertainty among evangelicals as to what exactly is “postliberalism.” Simply put: the “liberalism” in postliberalism is not meant to refer narrowly to progressive, leftish, revisionary thought per se. The target is, rather, those forms of broader modern liberalism which have produced certain ways of thinking about faith and the church which can be found in both conservative and in so-called “liberal” churches.

This is shown simply in the commitment to two priorities: (1) The priority of the rights and freedoms of the individual over those of the community and (2) The priority of the present experience of the individual in the moment over the past and over traditions.

Postliberals seek, in a host of ways, to resituate the individual more primarily in community and in tradition(s), correcting the distortions that they see in both right and left forms of “liberalism.” The current political situation and the way that so many Christians have ambivalence (rightly so) about both the “right” and the “left” is evidence of how relevant postliberal thought continues to be on this score. There remains a lot that evangelicals can learn from George Lindbeck.

Constructive Criticism

The notion that evangelicals have much to learn may seem condescending, ...

Continue reading...

from http://feeds.christianitytoday.com/~r/christianitytoday/ctmag/~3/oXmUDyPzbug/what-evangelicals-can-learn-from-lindbeck.html

0 notes

Text

Tweeted

Died: George Lindbeck, Father of Postliberal Theology https://t.co/SvYpLqwE5G

— Michael Hogg (@mhoggin) January 24, 2018

0 notes

Text

WHY YOU SHOULD BUY THIS BOOK: A COMPLETELY BIASED AND PARTIAL REVIEW

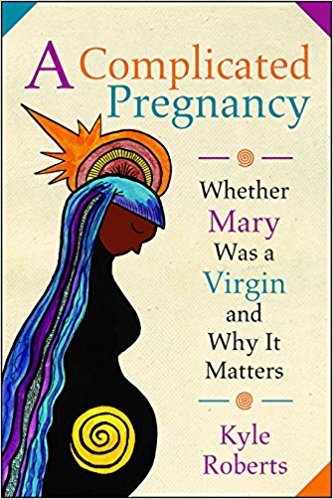

“A Complicated Pregnancy: Whether Mary Was a Virgin and Why It Matters” by Kyle Roberts

One should buy A Complicated Pregnancy for at least three reasons:

· it is short, smart, and accessible,

· everyone who has heard the story of Jesus has wondered whether it matters that Mary was a virgin or not,

· it is good theology, and by that, I mean, it is a book that is good at being theological without also being boring.

Now, granted, the author, Kyle Roberts, Dean of United Theological Seminary of the Twin Cities in St. Paul, Minnesota, is a dear friend; well, more like an older brother, really. And I work for the publisher. But that doesn’t mean that what I am about to say isn’t true.

The book is rock, solid gold. Here’s why.

Many of us live with some fairly serious theological questions that go unanswered. That’s because some of them are really hard to answer. I think I can speak for many of us when I say that a question that rises to the surface quite often would be the question asked and answered (sort of) in this book; Whether Mary Was a Virgin and Why It Matters.

Most of us do not know where to start, really. To figure it all out, we must first tackle some very thorny issues, the least of which is how to answer the question and what we need to know before we can get started. All this even before we can start exploring our options...

This book does a lot of that work for its lucky readers. For example, in A Complicated Pregnancy, Roberts:

· clarifies what we are actually asking about when we ask whether Mary was a virgin (virginal conception vs. virgin birth, immaculate conception vs. perpetual virginity, and so on),

· sorts through why asking questions about Mary can be such a scary proposition for many Christians,

· explores the (scant) biblical evidence for the virginal conception and examines how those texts were understood by early readers who were devoted to Jesus and his work,

· reviews how the virginal conception of Jesus in Mary has been treated throughout Christian history and what that may tell us about why it matters/doesn’t matter today,

· asks what science tells us about virgin conceptions, and how and why they happen (spoiler: they happen in the natural world more often that one would think!),

· connects theologies about Mary to attitudes in evangelical Christian culture about sex, sexuality, gender, and the body, and finally,

· tells us more about the figure of Mary and why she has been such a controversial and important figure, not just in Christianity, but in western culture at large. As it turns out, Mary isn’t only important for understanding who Jesus was; she’s inspired revolutions, labor strikes, and social movements around the world for centuries.

BUT...

What makes this book really unique though, is that Roberts takes the reader on a theological ride, not that different than that taken by the author himself. Roberts is not some bland, liberal Protestant intellectual. He was an evangelical seminarian, youth pastor, and conservative theologian for decades. He’s more a postliberal than a radical, actually, and he takes very traditional perspectives on the incarnation and resurrection of Jesus, as well as the bodily resurrection of the dead. And so, like all the ads on the travel sites will tell you, this book is as much about the journey it takes you on as it is about the destination; this book (and its author) cares as much about the process of asking hard theological questions as it does about offering answers, although it does not disappoint readers who are looking for them.

And so, yes, Roberts does offer his perspective on “Whether Mary Was a Virgin.” Spoiler: it’s complicated.

And as to “Why It Matters,” Roberts suggests that the question of Mary’s virginity doesn’t matter for the reasons that one might think. It’s actually not that central to Christianity, but what is important is what it tells about who Jesus is, what it means to think of Jesus as fully human, and what difference the fully human Jesus makes for the here and now.

In what Robert calls the “most vexing problem of all,” “the logic of the incarnation conflicts with the notion of a virginal conception” (134) since the whole point of the incarnation is to underscore the miracle of God’s entry to the fullness of being human. “Jesus Christ, the incarnate Son of God, experienced human life like the rest of us,” (172) including being conceived as a result of sex (like the rest of us). Roberts is open-hearted in his enthusiasm for the idea that, rather than threatening the most central tenants of Christian faith, asking serious questions about the virginal conception of Jesus in Mary leads to a deeper, more full understanding of what it means to say that Jesus, the Christ was human in the first place. And that, my friends, is what’s so complicated about Mary’s pregnancy.

As it turns out, nothing matters more (or less) than the question of whether Mary was a virgin. But not for the reason you may think.

0 notes

Quote

Frei contended that much of scriptural narrative is history-like without needing to be historical. The purpose of the Gospel stories is to narrate the identity of Jesus, he argued. For this reason many of the Gospel episodes function as illustrative anecdotes. They show us the kind of person that Jesus was. The test of their truth is not whether the particular incidents that they describe took place, but whether they truthfully narrate the identity of Jesus to us.

The Origins of Postliberalism by Gary Dorrien

1 note

·

View note

Text

Amanda MacInnis on Postliberal Thought

Amanda MacInnis has written a four part series on Postliberal theology.

The Role of the Church in Postliberal Thought — Strengths, and Some Concluding Thoughts

The Role of the Church in Postliberal Thought — The Problem of Antirealism

The Role of the…

View Post

0 notes

Text

"[Calhoun] taught us to use the time-honored orthodox term 'doctrine' once again with ease, and not even to be afraid of the word 'dogma.' In his lectures... 'orthodoxy' was a matter of broad consensus within a growing and living tradition with wide and inclusive perimeters. His theological teaching was above all generous, confident that divine grace and human reflection belonged together and that the revelation of God in Christ was no stranger in this world, for the universe was providentially led, and human history was never, even in the instances of the greatest follies, completely devoid of the reflection of the divine light.”

—Hans Frei, quoted by George Lindbeck in the "Introduction" to Robert Calhoun, Scripture, Creed, Theology

0 notes

Quote

In contrast to liberal individualism in theology, postliberal theology roots rationality not in the certainty of the individual thinking subject (cogito ergo sum, 'I think, therefore I am') but in the language and culture of a living tradition of communal life. The postliberals argue that the Christian faith be equated with neither the religious feelings of Romanticism nor the propositions of a Rationalist or fundamentalist approach to religion. Rather, the Christian faith is understood as a culture and a language, in which doctrines are likened to a "depth grammar" for the first-order language and culture (practices, skills, habits) of the church that is historically shaped by the continuous, regulated reading of the scriptural narrative over time. Thus, in addition to a critique of theological liberalism, and an emphasis upon the Bible, there is also a stress upon tradition, and upon the language, culture and intelligibility intrinsic to the Christian community. As a result, postliberal theologies are often oriented around the scriptural narrative as a script to be performed, understand orthodox dogmas (esp. the creeds) as depth-grammars for Christian life, and see such scriptural and traditional grammars as a resource for both Christian self-critique and culture critique.

Wikipedia, "Post-liberal Theology" (accessed 5 Sept 2011)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The structures of modernity press individuals to meet God first in the depths of their souls and then, perhaps, if they find something personally congenial, to become part of a tradition or join a church...

Thus the traditions of religious thought and practice into which Westerners are most likely to be socialized conceals from them the social origins of their conviction that religion is a highly private and individual matter."

—George Lindbeck, The Nature of Doctrine

0 notes

Quote

There is no such thing as a Christian theology which is not together with other things also a political theology.

Hans Frei

0 notes