#philippe charles duke of anjou

Text

A mythological portrait of King Louis XIV and the French royal family by French painter Jean Nocret.

#king louis xiv#philippe duke of orleans#henriette anne stuart#anne marie louise of orleans#queen henrietta maria#anne of austria#maria theresa of spain#louis grand dauphin#marie therese madame royale#philippe charles duke of anjou#marguerite louise of orleans#elisabeth marguerite of orleans#francoise madeleine of orleans#royal painting#art

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

inspired by @mihrsuri‘s awesome posts:

“While Charles regarded the Prince of Orange and Prince George of Denmark as suitable matches for his nieces, for his daughter and heir a mate was required who would willingly play second fiddle...”

“Princess Elizabeth was given a choice among the younger sons of Ernest Augustus, Elector of Brunswick-Lüneburg and his wife, Sophia of the Palatinate, a granddaughter of James IV and I. Elizabeth chose for her prince the handsomest of the brothers, Maximilian William, a third son three years her elder...” (Charles II and His Daughter Elizabeth II)

“The birth of Princess Elizabeth went a long way towards soothing anti-Catholic fears among the English population, with a Protestant heir standing between the Catholic Duke of York and the throne. The Queen’s position improved immensely..”

“Although her fondness did not extend to her father’s mistresses, the new Queen was inordinately fond of her half-sisters and brothers. Don Carlos accompanied his niece the Princess Royal on the occasion of her marriage to Philippe, Duc de Anjou, later King of Spain...”

“Elizabeth’s closest inner circle included her mother the Queen Mother, uncle the Duke of York, the younger of her surviving cousins the Lady Anne, and her half-sister Charlotte Lee, Countess of Lichfield...” (The Protestant Princess Who Saved England: Elizabeth Stuart and the Protestant Succession)

“Although the match had been set for years, as the time drew near for Max to leave for England, Sophia began to harbor misgivings. Her son was not content as a third son; he had been very pleased to have been chosen over his brothers but how long he would be contented to leave the reins of power in the hands of his wife?” "Max proclaimed himself very happy with his new bride. Elizabeth was not classically beautiful (she had too much of her father in her for that) but she was considered handsome. Max described her in letters to his mother and sister as 'tall and well-formed with dark curly hair and sensual lips'..." "The first clash came when Max, slighted over the Queen's choice of her brother for a honor he believed should have been his, lashed out by showing deliberate and obvious attention to one of his wife's ladies..." "Theirs was a tumultuous marriage but when the couple worked in concert, they could accomplish great things indeed... " "Did Max and Elizabeth feel love for one another? We'll never know for certain but what we do know is that whatever their arguments, they remained physically affectionate throughout their marriage..." (Jolly Prince Max: He Who Would Be King)

“Unlike her father and uncle, Elizabeth, who lacked close family ties to France, pursued a much less conciliatory policy towards France and one that aligned more closely with Parliament’s ...”

“Though the pair later married their eldest surviving daughter to a grandson of Louis XIV, they also married the rest of their offspring with the exception of Princess Charlotte into the other royal families of Europe...” (Politics in the Court of Queen Elizabeth and Prince Max)

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

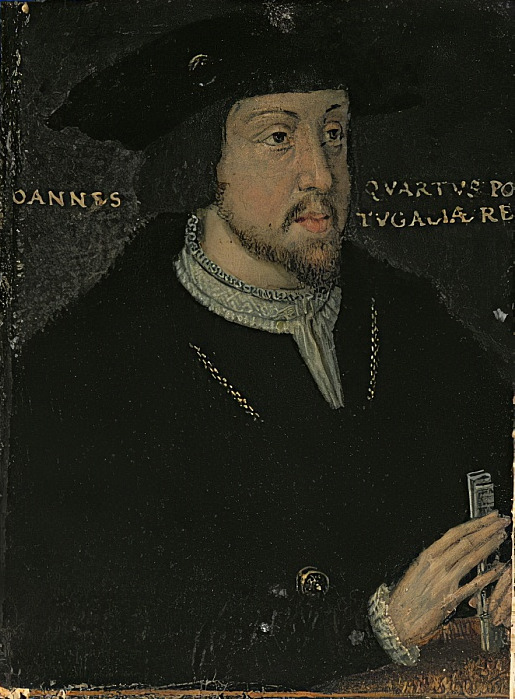

Royal Birthdays for today, March 3rd:

John II, King of Portugal, 1455

Luís of Portugal, Duke of Beja, 1506

Frederica of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, Queen of Hanover, 1778

Charles-Philippe of Orleans, Duke of Anjou, 1973

Maria Francisca, Portuguese Infanta, 1997

#john ii#luis of portugal#infanta maria francisca#charles philippe of orleans#Frederica of Mecklenburg-Strelitz#long live the queue#royal birthdays

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Daniel Auteuil and Isabelle Adjani in Queen Margot (Patrice Chéreau, 1994)

Cast: Isabelle Adjani, Daniel Auteuil, Jean-Hugues Anglade, Vincent Perez, Virna Lisi, Dominique Blanc, Pascal Greggory, Claudio Amendola, Miguel Bosé. Screenplay: Danièle Thompson, Patrice Chéreau, based on a novel by Alexandre Dumas. Cinematography: Philippe Rousselot. Production design: Richard Peduzzi, Olivier Radot. Film editing: François Gédigier, Hélène Viard. Music: Goran Bregovic.

In its initial release as La Reine Margot in France, Patrice Chéreau's historical epic was a huge critical and commercial success, winning awards at Cannes and in France's César Awards competition. It was less successful in America, where it was released as Queen Margot, receiving only an Oscar nomination for Moidele Bickel's costumes. One obvious reason is that American audiences are less keyed-in to 16th-century French history, and a passing acquaintance with the conflict between Catholics and Protestants that culminated in the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre in 1572 is essential to understanding the motives of the movie's characters. Things were not improved for American audiences by the decision of the distributor, Miramax, to cut 15 minutes from the film and turn it into a costume drama, centered on the romance of the Catholic Marguerite de Valois (Isabelle Adjani) and the Protestant La Môle (Vincent Pérez). At the behest of her mother, Catherine de' Medici (Virna Lisi), Marguerite has married a Protestant, Henri de Navarre (Daniel Auteuil), but she refuses to go to bed with her new husband. Feeling randy, she goes out into the streets to pick up a man, and has very passionate sex against a wall with La Môle, whom she later rescues during the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre. There's court intrigue involving the somewhat insane Charles IX (Jean-Hugues Anglade); his mother, Catherine; and his brother, the Duke of Anjou (Pascal Greggory). There are poisonings and boar hunts, and a lot of other stuff. The screenplay by Chéreau and Danièle Thompson is adapted from a novel by Alexandre Dumas, and neither screenplay nor novel should be relied on for historical accuracy. Adjani seems to struggle a bit with the vagaries of her character, whose sympathies shift from Catholic to Protestant and from man to man all too easily. The standout performance is that of Lisi, who makes the scheming Catherine a figure of some complexity.

0 notes

Text

Knights of the Order of the Crescent

Knights of the Order of the Crescent is a worthy discussion since we know that the crescent moon is an indigenous symbol from Southern Arabia, aka, Mexico, since Mexico was Southern Arabia and Mexico means, “In the center of the Moon”: https://rb.gy/himgj1.

#foogallery-gallery-3261 .fg-image { width: 150px; } #foogallery-gallery-3261 .fg-image { width: 150px; }

Map of Mayaca, Florida (Ethiopia)

There is a town in Ethiopia called Mayo, Ethiopia. The name Mayo is the same as Maya (Mayans), so we are dealing with the Mayans. There was once a Mayan city in Florida called Mayaca (see post image of map), which is further proof that the Mayans established La floridas (Ethiopia Superior/ Tameri). This city was obviously named after the Mayas/ Mayans since we can see their tribal name of Maya in Mayaca (Maya-ca). Mayaca is now extinct and so is the Mayaca Tribe (Mayaca people), and we can blame the Spanish invasion (the Holy Wars) of the 1500's for their extinction; however, Florida still has Port Mayaca as evidence of a city now gone.

Duke of Milan (1454);

SFORZA (François-Alexandre) Quarterly: 1st and 4th Or, to the eagle Sable crowned of the first (LOMBARDY); 2nd and 3rd, Argent, to the bisse Azure in pale, crowned Or, giving birth to a child Gules (VISCONTI-MILAN). Duke of Milan (1454); natural son of Muzio Attendolo dit Sforza, lord of Cotignola, and Lucrezia Trezana or Tresciano; husband: 1° of Polyxène Ruffo, widow of Jacques Marilli (?) Grand Seneschal of the Kingdom of Naples, daughter of Charles Ruffo, Count of Montalto and Corigliano, and of Cevarella de Saint-Séverin; 2° (August 1, 1441) of Blanche-Marie Visconti, natural daughter of Philippe-Marie Visconti, Duke of Milan; born at San-Miniato (Tuscany), July 25, 1401, died at Milan, March 8, 1466.

First Baron of Maine, Viceroy of Sicily and Anjou

CHAMPAGNE (Peter I of) Sable, fretty Argent; a chief or charged with a lion issanl gules (1). Currency (2): Sta closes. Lord of Champagne, Pescheseul, Lonvoisin, Bailleul and Parcé, Prince of Montorio and Aquila, First Baron of Maine, Viceroy of Sicily and Anjou; third son of Jean III of Champagne and Ambroise de Crénon; married, according to contract of April 22, 1441, with Marie de Laval, sister of Guy de Laval (see this name), and daughter of Thibaut and Jeanne de Maillé-Brézé; died in Angers, almost a hundred years old, on October 15, 1486, and buried on the 22nd of the same month, in the church of Saint-Martin de Parce (3). This valiant knight, who had distinguished himself in many battles, won two great victories against the English: the first in 1442, in the plain of Saint-Denis d'Anjou, and the second in 1448, before Beaumont-le-Vicomte. The following year, Jean d'Anjou gave him the order to help Charles VII against the English, and he covered himself with glory at the Battle of Formigny (1450).

ANJOU (Charles I of) Count of Maine

ANJOU (Charles I of) Azure, semé of fleurs-de-lis Or, to the lion Argent set in quarter; bordered gules. Count of Maine, Guise, Mortain, viscount of Châtellerault, lieutenant general for the king in Languedoc and Guyenne; third son of Louis II of Sicily and Yolande of Aragon; married: 1°, before 1434, with Cobelle Ruffo (2), widow of Jean-Antoine Marzano, Duke of Sessa, Prince of Rossano, daughter of Charles Ruffo, Count of Montalto and Corigliano, Grand Justice of the Kingdom of Naples, and of Cevareila de Saint-Séverin (see this name); 2°, by contract of January 9, 1443, with Isabelle de Luxembourg, daughter of Pierre de Luxembourg, count of Saint-Pol, and of Marguerite des Baux; born in the castle of Montils-les-Tours, October 14, 1414; died at Neuvy, in Touraine, on April 10, 1472, and buried in the church of Saint-Julien in Le Mans. (2) Through this alliance, Cobelle Ruffo had become the sister-in-law of three kings, Louis III of Sicily, René of Anjou and Charles VII. Polyxène Ruffo, his sister, first married François-Alexandre Sforza (see this name).

Baron of Mison

AGOULT (Fouquet or Foulques d') Or, to the ravishing wolf Azure, armed, langued and vilené Gules (1). Baron of Mison, of La Tour-d'Aigues, of Sault and of Forcalquier, lord of Thèze, Barret, Volone, La Bastide, Peypin, Niozelles, etc., chamberlain of René d'Anjou, viguier of Marseilles (1443, 1445 and 1472); son of Raymond and Louise de Glandevès-Faucon, his second wife; married: 1° with Jeanne de Beaurain; 2° with Jeanne de Bouliers; died without posterity at La Tour-d'Aiguës in 1492, nearly 100 years old. Fouquet d'Agoult had been nicknamed by his contemporaries the Great and the Illustrious, in view of his love of justice, his magnificence and his liberality. Nostradamus (2) reports that "after the death of this so good and so excellent Roy (René d'Anjou) several and various eulogies, epitaphs and learned compositions were placed on his tomb, in the church of the Convent of the Carmelites of the City of Aix...The eulogies were in various languages, Hebrews, Greeks, Latins, French, Italians, Cathalans and Provencals, which the magnificent Fouquet d'Agoult, lord of Sault, had collected and transcribed exactly by the express command de la Reyne his second wife.

Moslem-Jerusalem under the Order of the Cresent, 1070

Muslem-Jerusalem from 1070 under the order of the Cresent. Moslem-Jerusalem, which looks very Moorish with the Crescent moons at the top of those Maurice domes. I love the Phoenician purple trim too at the top. This image is a full-page miniature of Jerusalem and the Dome of the Rock Image taken from feature 5 of Book of Hours, Use of Paris ('The Hours of René d'Anjou'). Written in Latin, calendar, and rubrics in French.

King René of Anjou

The Ordre du Croissant (Order of the Crescent; Italian: Ordine della Luna Crescente) was a chivalric order founded by Charles I of Naples and Sicily in 1268. It was revived in 1448 or 1464 by René I of Naples, the king of Jerusalem, Sicily, and Aragon (including parts of Provence), to provide him with a rival to the English Order of the Garter. René was one of the champions of the medieval system of chivalry and knighthood, and this new order was (like its English rival) neo-Arthurian in character. Its insignia consisted of a golden crescent moon engraved in grey with the word LOZ, with a chain of 3 gold loops above the crescent. On René's death, the Order lapsed. The Order of the Crescent, also known as "Order of the Crescent in the Provence,” a French chivalric order was founded on 11 August 1448 in Angers by King Rene of Provence as a court order. The order, which united itself, features from knighthood and spiritual orders, and counted up to 50 knights, of which can be dukes, princes, marquises, viscounts and knights with four quarters of nobility.

A French Canadian Maur by the name of Ann Marie Bourassa sent me a link to the Armorial Chevaliers (Knights) of the Order of the Crescent and the images in this post spoke to my DNA, since my maternal surname, “Chavis” means the Goat and Brave boy: https://rb.gy/qk2k10.

Chavis/ Chavers is also short for Chevaliers, since the Chavis are a Royal family of knights that is associated with bravery and passing the BAR. Chevaliers is French for Knights since the number one code of the knights is chivalry, which means bravery. During the old-world chivalry (honor) was established from being brave in battle, and cavalry is another word that is derived from chevaliers since cavalry means an army of mounted braves (Knights) on horses.

In 1066 during the Battle of Hastings, my French royal family of Shivers, which is French for Chavis, as knights, helped the French Viking King, “William the Conqueror,” a Danite, conquer England with the aid of two dragons and were given the Shivers Mountains in England by William the Conqueror due to the acts of Chivalry (bravery=Knighthood) on the battlefield: https://rb.gy/n9vlao.

Here is the link to the Armorial Knights of the order of the Crescent: https://rb.gy/y2hpa4. This link is in French, but you can use Goggle Translate to translate the French into English.

Please, avoid the hijack with the whitewash when reading the Armorial Knights link, because the original French were the Franks or Gauls (Gullah Geechee/ Galilee), and they were French Maurs (Merovingians): https://rb.gy/posjrm.

“Franks (Franci), a Germanic people who conquered Gallia (Gaul), and made it Francia (France).” [End quote from Oxford Classical Dictionary]. “Gaul, French Gaule, Latin Gallia, the region inhabited by the ancient Gauls, comprising modern-day France and parts of Belgium, western Germany, and northern Italy”: https://www.britannica.com/place/Gaul-ancient-region-Europe.

The Americas has the most place names associated with Gaul/ Gales/ Gules/ Gola/ Galley/ Gullah/ Galilee/ Gaelic (France). For example, Galesburg, Illinois; Galilee, Pennsylvania; Angola, Louisiana; Angola, Indiana, etc. Some of the African slaves allegedly came from Angola, aka, the Congo (Congo, Alabama*), which is a country allegedly in Africa on the Slave Coast. Gola, which is short for Angola (An-Gola), is also Gula as in Gullah Geechee – Seminole and Creek (Greek) Indians: https://msuweb.montclair.edu/~sotillos/moore.htm.

Guale was a historic Native American chiefdom (Tribe) of Mississippian culture peoples located along the coast of present-day Georgia and the Sea Islands. This tribe of Guale Indians were Maurs (Maur-iners as in Marine and Mar/ Mer as in sea), aka, Sea people. Guale was once a city on the Sea Coast of Georgia that is now extinct and so is this tribe of Indians (Washitaw Muurs = Yamasees and the five civilized tribes), due to Spanish conquest: https://www.americaistheoldworld.com/gibraltar-of-the-west/.

In South America we have the Spanish equivalent to the Gullah Geechee, the “Gualeguaychú.” Gualeguaychú is a city in the province of Entre Ríos, Argentina, on the left bank of the Gualeguaychú River (a tributary of the Uruguay River). In Mexico, we have Guatemala, which is a derivative of Gaul since the prefix Guate in Gutemala is Gaul.

This book, “Africa vs. America,” demonstrates that Europeans copied ancient Ghana that was in South America (Guyana) and built a second Ghana on the other coast [Africa], which is known as Congo or Angola. Africa vs. America,” by Isabel Alvarez: https://www.americaistheoldworld.com/ancient-ghana-is-guyana/.

This FB post deals with a French Merovingian Queen, nicknamed “The She Wolf,” since she convinced a Baron (wizard), Lord Roger Mortimer, to help her to overthrow her gay husband, King Edward II of England to take the crown: https://rb.gy/7g9b4s.

Speaking of the She Wolf, the Capitoline Wolf is the She Wolf and is a symbol of the founding of Rome. The wolf is a sacred symbol of the Turks and the Danites. The Americas has 13 Capitoline Wolf Statues, which suggests that the greater Rome or Imperial Rome was in the Americas. Rome is derived from the Egyptian word Ramen and the Hebrew word Rimon, which means pomegranate. The pomegranate is a symbol of Granada Land (the promised land), which was in the Americas: https://www.americaistheoldworld.com/imperial-rome-and-italy-superior/.

The Armorial Knights of the order of the Crescent has a few coats of arms with the She Wolf in the center of the moon. Mother Mary/ Maya/ Meru, aka, the Queen of Heaven, is shown in many images as the Venus Star Transit, which is the Mayan 5-pointed Star, standing in the center of the crescent moon. The wolf is code for the Dragon, aka, the constellation Draco when its Star Theban was the Pole Star or the North Star.

Who was Rene d’Anjou?

In this post are some images of the Royal Knights’ coat of arms of the Order of the Crescent, instituted by King René d’Anjou, ms. Fr. 5225. Statues of the Order of the Crescent, founded by René d’Anjou (1448), ms. Fr. 25204. (Source: gallica.bnf.fr, National Library of France).

The Ordre du Croissant (Order of the Crescent; Italian: Ordine della Luna Crescente) was a chivalric order [knights’ order] founded by Charles I of Naples and Sicily in 1268. It was revived in 1448 or 1464 by René I of Naples, the king of Jerusalem, Sicily and Aragon (including parts of Provence), to provide him with a rival to the English Order of the Garter. René was one of the champions of the medieval system of chivalry and knighthood, and this new order was (like its English rival) neo-Arthurian in character. Its insignia consisted of a golden crescent moon engraved in grey with the word LOZ, with a chain of three gold loops above the crescent. On René’s death, the Order lapsed.

The Armorial Knights of the Order of the Crescent, also known as “Order of the Crescent in the Provence,” a French chivalric order was founded on 11 August 1448 in Angers by King Rene of Provence as a court order. The order, which united itself, features from knighthood and spiritual orders, and counted up to fifty knights, of which can be dukes, princes, marquises, viscounts, and knights with four quarters of nobility.

The Knights committed themselves to mutual assistance and loyalty to the order which, after the Provence became part of France in 1486, was soon forgotten. Ackermann mentions this knighthood as a historical order of France.

In this post is a poorly whitewashed image of King Rene of Anjou since he is still swarthy (dark/ Black) in his image. King Rene was the grandson of King John II of France, aka, John the Good, who was undoubtedly a Naga/ Negro: https://rb.gy/onckrm.

René of Anjou (Italian: Renato; Occitan: Rainièr; Catalan: Renat; 1409–1480) was Duke of Anjou, King of Jerusalem, King of Sicily, King of Aragon (Gules), and Count of Provence [Province, Maine*] from 1434 to 1480, who also reigned as King of Naples as René I from 1435 to 1442 (then deposed as the preceding dynasty was restored to power). Having spent his last years in Aix-en-Provence, he is known in France as the Good King René (Occitan: Rei Rainièr lo Bòn; French: Le bon roi René).

René was a member of the House of Valois-Anjou, a cadet branch of the French royal house, and the great-grandson of John II of France. He was a prince of the blood, and for most of his adult life also the brother-in-law of the reigning king Charles VII of France. Other than the aforementioned titles, he was for several years also Duke of Bar and Duke of Lorraine.

René was born on 16 January 1409 in the castle of Angers.[2] He was the second son of Duke Louis II of Anjou, King of Naples, by Yolanda of Aragon.[2] René was the brother of Marie of Anjou, who married the future Charles VII and became Queen of France.[3]

Anjou is just a Latinized way of saying Andros/ Andrews, so we are dealing with Saracens (old Arabs) of the lost 10 lost tribes of Israel that were descendants of the first Apostle Saint Andrew: https://the-red-thread.net/genealogy/andrews.html.

Greater France or France Superior in the Americas:

If you have read my post about Imperial Rome and Italy Superior you already know that Italy Superior was La Floridas and there is also a Naples, Florida, which suggests that Rene Anjou was once the king of Naples, Florida since La Floridas was the original Italy. Remember that France borders Italy, which means that since Italy Superior was in the Americas Greater France or France Superior was also in the Americas.

Now, if we include Gules/ Gual (Aragon) and Maine, it leaves no doubt that this history is referring to Greater France in the Americas since the Imperial Rome and Italy Superior post proves that Africa, Europe, and the Middle East was originally in the Americas.

Maine and the New England states were once part of the Nova France and this territory was once known as Nova France (New France), according to old maps from the 1500’s – 1700’s, however, we know that it is nothing new about Nova France since the Americas is the East (the Orient) and the old world. Maine also has a Bar Harbor, now a resort for the wealthy. Notice that when you read the description of the coat of arms in the Armorial Knights link you will see a few references to Bar and Maine, which suggests that ancient Frankish (French) history is referring mostly to the Americas.

France borders Italy, according to modern-day maps, therefore, this post is more evidence confirming that the original France was in the Americas since Florida was Italy Superior.

King Anjou was born and buried in Angers, France. Angers sounds a lot like Algiers, Louisiana. Algiers was part of the Ottoman Empire that was originally in the Americas: https://www.americaistheoldworld.com/the-ottoman-empire-in-the-americas/.

The French and the Ottoman Turks as Moormans (Danites=Vikings=Sea people) were blood allies against Spain (Rome) during the Crusades or Holy Wars. Louisiana has France written all over it since Louisiana is called Cajun Country. Plus, the prefix of Louis in Louis-iana is a French name that is associated with a long list of French Kings. Cajun and Acadian (Akkadian) are the same word. In fact, Louisiana used to be a part of the Acadian Republic. Louisiana is called the boot kicking state since Louisiana is shaped like a boot, and so is Italy and Florida. Louisiana has a French Quarters and the people called themselves Cajuns (Acadians).

Additionally, the city of New Orleans, Louisiana, is called the Crescent City and it shares the same place names as Orleans, France. Louisiana also has Parishes (Parish=Paris), which is derived from Paris, as in Paris, France. Paris means “For Isis” or “City of Isis,” and Paris is short for Paradise. Baton Rouge (Louisiana) is a French word that means Red Stick.

The New Orleans Saints logo is the fleur-de-lis (Florida*). It’s a French word that means lily flower in English. French Maurs (High Priest of Anu) known as the Merovingians introduced the fleur-de-lis as a symbol of France, which is sometimes spelled fleur-de-lys; and it is a stylized lily or iris commonly used for decoration. In fact, translated from French, fleur-de-lis means “lily flower.” Fleur means “flower,” while lis means “lily.” The interesting thing about the fleur-de-lis or Lily Flower is that it is derived from the Bee, and it is just an upside-down Bee: https://rb.gy/jpasca.

AGOULT (Fouquet or Foulques d’)

Or, to the ravishing wolf Azure, armed, langued and vilené Gules (1).

Baron of Mison, of La Tour-d’Aigues, of Sault and of Forcalquier, lord of Thèze, Barret, Volone, La Bastide, Peypin, Niozelles, etc., chamberlain of René d’Anjou, viguier of Marseilles (1443, 1445 and 1472); son of Raymond and Louise de Glandevès-Faucon, his second wife; married: 1° with Jeanne de Beaurain; 2° with Jeanne de Bouliers; died without posterity at La Tour-d’Aiguës in 1492, nearly 100 years old.

Fouquet d’Agoult had been nicknamed by his contemporaries the Great and the Illustrious, in view of his love of justice, his magnificence and his liberality. Nostradamus (2) reports that “after the death of this so good and so excellent Roy (René d’Anjou) several and various eulogies, epitaphs and learned compositions were placed on his tomb, in the church of the Convent of the Carmelites of the City of Aix…The eulogies were in various languages, Hebrews, Greeks, Latins, French, Italians, Cathalans and Provencals, which the magnificent Fouquet d’Agoult, lord of Sault, had collected and transcribed exactly by the express command de la Reyne his second wife.

(1) All the genealogists and heraldists describe the d’Agoult coat of arms in the terms we have just used; however, the wolf is always represented crawling and not ravishing, that is to say holding its prey in the mouth. We didn’t want to change anything in the accepted description; but it was necessary to point out that it does not agree with the representation of the coat of arms. In 1220, the seal of Raymond II d’Agoult bore a passing wolf.

(2) History and Chronicle of Provence, p. 646.

ANJOU (Charles I of)

Azure, semé of fleurs-de-lis Or, to the lion Argent set in quarter; bordered gules.

Count of Maine, Guise, Mortain, viscount of Châtellerault, lieutenant general for the king in Languedoc and Guyenne; third son of Louis II of Sicily and Yolande of Aragon; married: 1°, before 1434, with Cobelle Ruffo (2), widow of Jean-Antoine Marzano, Duke of Sessa, Prince of Rossano, daughter of Charles Ruffo, Count of Montalto and Corigliano, Grand Justice of the Kingdom of Naples, and of Cevareila de Saint-Séverin (see this name); 2°, by contract of January 9, 1443, with Isabelle de Luxembourg, daughter of Pierre de Luxembourg, count of Saint-Pol, and of Marguerite des Baux; born in the castle of Montils-les-Tours, October 14, 1414; died at Neuvy, in Touraine, on April 10, 1472, and buried in the church of Saint-Julien in Le Mans.

(2) Through this alliance, Cobelle Ruffo had become the sister-in-law of three kings, Louis III of Sicily, René of Anjou and Charles VII. Polyxène Ruffo, his sister, first married François-Alexandre Sforza (see this name).

ANJOU (Jean d’)

Per fess of one party, of two, which makes six quarters: 1 barage Argent and Gules, of eight pieces (HUNGARY); 2nd, Azure, strewn with fleurs-de-lis Or, a label Gules, five pendants in chief (ANJOU-SICILY); 3 Argent, to the cross of Jerusalem Or, at angle (JERUSALEM); 4th, azure, strewn with fleurs-de-lis or, a border gules (ancient ANJOU); 5th Azure, strewn with recrossed crosses set foot Or, two bars backed by the same debruising over all (BAR): 6th Or, a bend Gules charged with three alerions Argent ( LORRAINE); a label Gules three pendants in chief, debruising on the large quarters.

Duke of Calabria and Lorraine, senator of the Crescent (1470); eldest son of René d’Anjou and Isabelle de Lorraine; married, by treaty of April 2, 1437, with Marie de Bourbon, daughter of Charles I, Duke of Bourbon, and Agnès de Bourgogne; born in Toul on August 2, 1426, died in Barcelona on December 16, 1470, and buried in Angers, in the church of the Cordeliers (1).

(1) On a glass roof of this church, this prince was represented on his knees, his hands joined, a floral crown on his head, and wearing a loose coat with a turned down collar. In front of him was the coat of arms described above, supported by the emblem of the order of the Crescent with its motto. (MONTFAUCON, op. cit., t. II, pl. LXI11). These arms are absolutely identical to those which appear on a counter-seal of Jean d’Anjou, affixed to a document of 1465 (DOUET D’ARCQ, Collection de sceaux, t. I, n°789).

ANJOU (René d’)

Cut from one, from two, which makes six quarters; to 1 of HUNGARY; at 2 d’ANJOU-SICILY; at 3 of JERUSALEM; at 4 d’ANJOU old; at 5 of BAR; at 6 LORRAINE; over all Or, four pales Gules (ARAGON).

King of Naples, Sicily, Jerusalem and Aragon, Duke of Anjou, Lorraine and Bar, Count of Provence, Senator of the Crescent (1449); son of Louis II, Duke of Anjou, King of Naples, and Yolande of Aragon; married, in first marriage, by treaty of March 20, 1419, with Isabelle de Lorraine, eldest daughter and heiress of Charles II, Duke of Lorraine, and of Marguerite de Lorraine; in second marriage, September 10, 1454, with Jeanne de Laval, daughter of Guy XIV, Count of Laval, and Isabelle de Bretagne; born in Angers on January 16, 1409, died in Aix on July 10, 1480, and buried in the church of Saint-Maurice in Angers on October 26, 1481.

From the institution of the Armorial Knights of the Order of the Crescent, King René accompanied these coats of arms (1) (still existing in 1620, at Saint-Maurice d’Angers) with the insignia of the order (2), which he had painted and sculpted on a large number of monuments and works of art, to engrave on its seals (3) and to embroider (4) on its tapestries and ceremonial costumes.

(1) On the subject of the various coats of arms carried successively by René, see our work: La Croix de Jerusalem dans le Blason, p. 14.

(2) Ung radiant and marvelous crescent,

Garny of fine gold and white enamel, Of which

there was in frank writing,

Loz in crescent in engraved and understood,

Such motto had this lord taken.

Not without reason, for his loz would grow

On all living beings who had loz and be.

(OCTAVIE DE SAINT-GELAIS, Le Séjour de l’Honneur.)

(3) Some of these seals have a double crescent on the reverse that Mr Douet d’Arcq (collection of seals, n°11783) took for two bags or stacked purses.

(4) In 1448, Pierre du Villant, painter and embroiderer to the King of Sicily, two professions closely united in the Middle Ages, executed four embroidered crescents for his new order of chivalry (LECOY DE LA MARCHE, Extracts from accounts and memorials, n ° 632).

CHAMPAGNE (Peter I of)

Sable, fretty Argent; a chief or charged with a lion issanl gules (1). Currency (2): Sta closes.

Lord of Champagne, Pescheseul, Lonvoisin, Bailleul and Parcé, Prince of Montorio and Aquila, First Baron of Maine, Viceroy of Sicily and Anjou; third son of Jean III of Champagne and Ambroise de Crénon; married, according to contract of April 22, 1441, with Marie de Laval, sister of Guy de Laval (see this name), and daughter of Thibaut and Jeanne de Maillé-Brézé; died in Angers, almost a hundred years old, on October 15, 1486, and buried on the 22nd of the same month, in the church of Saint-Martin de Parce (3).

This valiant knight, who had distinguished himself in many battles, won two great victories against the English: the first in 1442, in the plain of Saint-Denis d’Anjou, and the second in 1448, before Beaumont-le-Vicomte. The following year, Jean d’Anjou gave him the order to help Charles VII against the English, and he covered himself with glory at the Battle of Formigny (1450).

(1) In the 17th century, this family sought to attach itself to the illustrious house of the Counts of Champagne and took its arms, which are: Azure with a silver band, bordered by two

cotices potent and counter-potentiated Golden.

(2) Motto and coat of arms still visible in 1620, in the chapel of the Knights of the Crescent in Saint-Maurice d’Angers.

(3) The epitaph engraved on his tomb had been composed, it seems, by the king.

SFORZA (François-Alexandre)

Quarterly: 1st and 4th Or, to the eagle Sable crowned of the first (LOMBARDY); 2nd and 3rd, Argent, to the bisse Azure in pale, crowned Or, giving birth to a child Gules (VISCONTI-MILAN).

Duke of Milan (1454); natural son of Muzio Attendolo dit Sforza, lord of Cotignola, and Lucrezia Trezana or Tresciano; husband: 1° of Polyxène Ruffo, widow of Jacques Marilli (?) Grand Seneschal of the Kingdom of Naples, daughter of Charles Ruffo, Count of Montalto and Corigliano, and of Cevarella de Saint-Séverin; 2° (August 1, 1441) of Blanche-Marie Visconti, natural daughter of Philippe-Marie Visconti, Duke of Milan; born at San-Miniato (Tuscany), July 25, 1401, died at Milan, March 8, 1466.

As you can see, the Armorial Knights of the Order of the Crescent were very distinguished and extraordinary gentlemen and so was their King, Rene of Anjou since King Rene was a Saracen (Moslem) that was the King of Jerusalem, Sicily, Naples, and Aragon. In this post is an image of Moslem-Jerusalem, which looks very Moorish with the Crescent moons at the top of those Maurice domes. I love the Phoenician purple trim too at the top. This image is a full-page miniature of Jerusalem and the Dome of the Rock Image taken from feature 5 of Book of Hours, Use of Paris (‘The Hours of René d’Anjou’). Written in Latin, calendar, and rubrics in French: https://picryl.com/media/jerusalem-from-bl-eg-1070-f-5-4d2417.

The royal coats of arms of the Knights of the Order of the Crescent display powerful images of occult symbols like the kingfish (fisher king), the Falcon (Horus), and the Bee/ Beetle. The Fleur-de-lis symbol is an upside-down bee. We know that the study of the birds (falcons) and the bees/ beetles is real sex (love) through alchemy, and this advanced knowledge (magic) that was acquired from Thoth/ Thought was used to create an Eden style of government or Ethiopia = Utopia that was based on free energy and a resource-based economy: https://www.americaistheoldworld.com/teotihuacan-is-the-home-of-thoth/.

The fisher kings who were Fishers of men, aka, Magi’s, were the High Priest of Anu (Maurs) from Nineveh, which was Jacksonville, Florida, and surrounding areas. Nineveh means place of fish or House of fish and is the home of Prophet Jonah of the Bible: https://www.americaistheoldworld.com/nineveh-was-jacksonville-florida/.

Speaking of Jonah, a fish/ whale swallowed him for 3 days and then spit him out, which is code for him being born from a dragon, making Jonah a messiah, a Christ-king, and/or a Dragon-king: https://rb.gy/dsgf9g.

In this post is the coat of arms of royal knight, SFORZA (François-Alexandre), that depicts a Maur (High priest of Anu) being born from a blue dragon since serpents/ dragons don’t eat their prey feet-first. Also, notice the double headed Turkey of the Holy Roman Empire on the coat of arms. People think that this bird is an Eagle when it really is a Turkey, since Turkeys have beards and Eagles don’t. If you view different images of Hapsburg (Holy Roman empire) coat of arms you see that the bird on this coat of arms is clearly a double headed Turkey with a red beard. The Turkey is indigenous to the Americas and so is the Roman Empire. The Turkey is a hybrid bird that was spliced together with light codes (sound frequencies), aka, light alchemy, by Turkmen/ Moorman long ago using a combination of the Tukey Buzzard and the Chicken (the base metals) to create another meat source known as Turkey (the gold or good product).

I know this Roman History is confusing because Rome was a global empire that was on both sides of the world, however, the legit honorable Roman Empire that was in the Americas and under French Washitaw rule was overthrown by the duplicate Christian and Catholic Rome in Europe since the American version of the Romans were Saracens (Moslems) and pagans (Hebrews) that were labeled as infidels, in the eyes of the duplicate Roman hijack.

The post Knights of the Order of the Crescent appeared first on America is the Old World.

source https://www.americaistheoldworld.com/knights-of-the-order-of-the-crescent/?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=knights-of-the-order-of-the-crescent

1 note

·

View note

Text

NAMES MASTERLIST**

under the cut you will find 45+ names inspired by 18th century FRENCH ROYALTY & ARISTOCRACY including examples of their usage in history. please like/reblog if you found this useful!

**compound names were very common, and would often be referred to by just one or two of the names (ei, marie louise élisabeth was called madame élisabeth, anne henriette was madame henriette). some names seen as “feminine” in english speaking countries, such as marie, are traditionally used in compound names for all genders without changes in spelling

names taken from women in history:

louise: marie louise élisabeth (madame royal, daughter of louis xv), maire louise (fille de france, daughter of louis xv)

élisabeth: “babette” marie louise élisabeth

marie: marie antoinette (queen of france), marie adélaïde (fille de france, daughter of louis xv), marie-louise (fille de france, daughter of louis xv)

thérèse : marie thérèse félicité (fille de france, daughter of louis xv), marie thérèse (daughter of louis xvi)

anne: anne henriette (fille de france, daughter of louis xv)

henriette anne henriette (fille de france, daughter of louis xv), jeanne louise henriette campan (ladies maid, educator of many of louis xv’s daughters)

adélaïde: marie adélaïde (fille de france, daughter of louis xv)

sophie: sophie philippine elisabeth justine (fille de france, daughter of louis xv), sophie hélène béatrix (fille de france, daughter of louis xvi)

jeanne: jeanne poisson (madame de pompadour, maîtresse-en-titre to louis xv)

félicité: pauline félicité de mailly-nesle (mistres of louis xv), marie thérèse félicité (fille de france, daughter of louis xv)

victoire: victoire louise marie thérèse (fille de france, daughter of louis xv)

zéphyrine: marie zéphyrine (petite-fille de france, daughter of louis, dauphin of france)

isabelle: marie isabelle de rohan

angélique: marie isabelle gabrielle angélique (duchess of tallard),

clotilde: marie adélaïde clotilde xavière (petite-fille de france, daughter of louis dauphin of france)

hélène: élisabeth philippe marie hélène (petite-fille of france, daughter of louis dauphin of france), sophie hélène béatrix (fille de france, daughter of louis xvi)

amélie: amélie florimond (likely an illegitimate daughter of louis xv)

agathe: agathe louise de saint-antoine de saint-andré (illegitimate daughter of louis xv)

charlotte: marie thérèse charlotte (madame royale, daughter of louis xvi)

yolande: yolande de polastron (duchess of polignac)

gabrielle: yolande martine gabrielle de polastron (duchess of polignac)

martine: yolande martine gabrielle de polastron (duchess of polignac)

aglaé: aglaé louise françoise gabrielle de Polignac

beatix: sophie hélène béatrix (fille de france, daughter of louis xvi)

diane: diane louise augustine de polignac (lady in waiting)

augustine: diane louise augustine de polignac (lady in waiting)

julie: louise julie de mailly-nesle (mistress of louis xv, comtesse de mailly)

hortense: hortense félicité de mailly-nesle (marquise de flavacourt)

françoise: françoise de mazarin (lady in waiting)

names taken from men in history:

louis: literally all the kings of the 18th century. louis xiv, louis xv, louis xvi

auguste: louis auguste (louis xvi of france), jules auguste armand marie (count of polignac)

françois: louis joseph xavier françois (dauphin of france), étienne françois (marquis de stainville, duc de choiseul)

ferdinand: louis ferdinand (dauphin of france)

phillipe: phillippe louis (duc of anjou, fils de france, son of louis xv)

charles: charles emmanuel marie magdelon (marquis du luc, son of louis xv), charles phillippe (count of artois, charles x)

joseph: louis joseph xavier (duke of burgundy, son of louis dauphin of france)

xavier: louis joseph xavier (duke of burgundy, son of louis dauphin of france), xavier marie joseph (duke of aquitaine, son of louis dauphin of france)

jules: armand jules françois (duke of polignac), jules auguste armand marie (count of polignac)

armand: armand jules françois (duke of polignac), jules auguste armand marie (count of polignac)

henri: camille henri melchior (count of polignac)

camille: camille henri melchior (count of polignac)

marie: jules auguste armand marie (count of polignac)

étienne: étienne françois (marquis de stainville, duc de choiseul)

césar: césar gabriel de choiseul (duc de praslin)

gabriel: césar gabriel de choiseul (duc de praslin)

jean: jean-frédéric phélypeaux (count of maurepas)

frédéric: jean-frédéric phélypeaux (count of maurepas)

76 notes

·

View notes

Photo

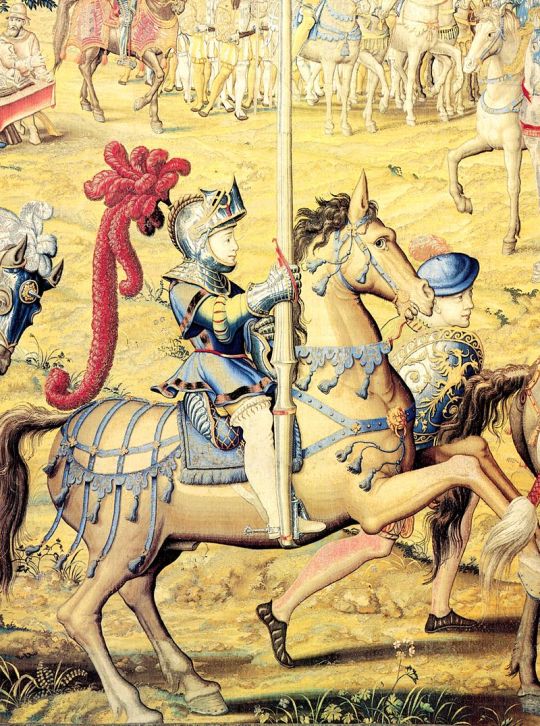

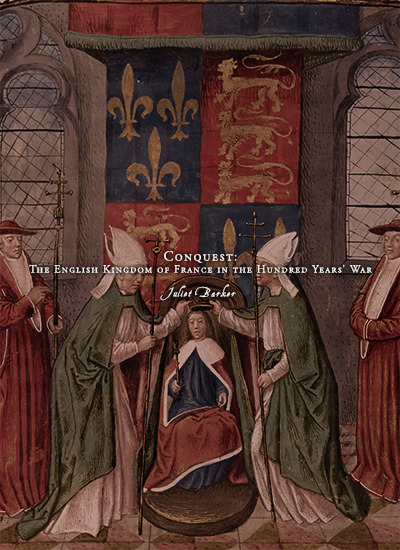

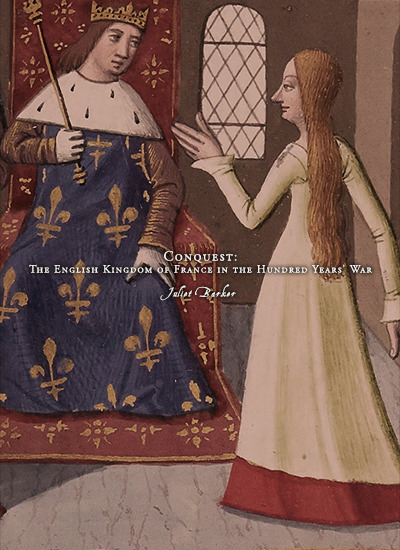

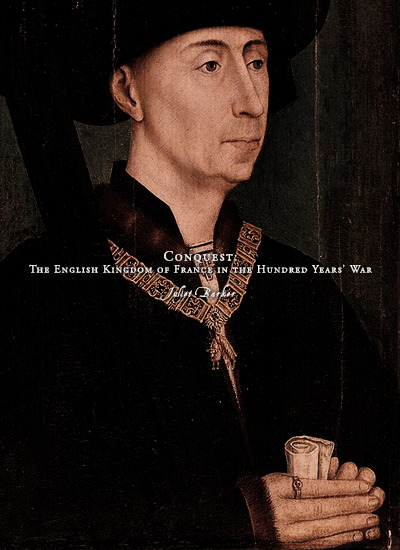

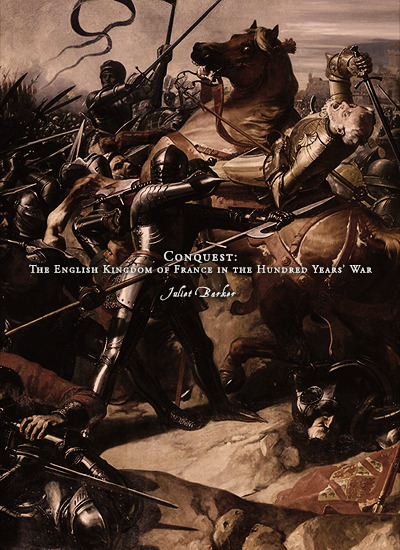

Favorite History Books || Conquest: The English Kingdom of France in the Hundred Years’ War by Juliet Barker ★★★☆☆

The Hundred Years’ War is defined in the popular imagination by its great battles. The roll-call of spectacular English victories over the French is a source of literary celebration and national pride and even those who know little or nothing about the period or context can usually recall the name of at least one of the most famous trilogy – Crécy, Poitiers, Agincourt. It is curious therefore that an even greater achievement has been virtually wiped from folk memory. Few people today know that for more than thirty years there was an English kingdom of France. Quite distinct from English Gascony, which had belonged to the kings of England by right of inheritance since the marriage of Eleanor of Aquitaine and Henry II in 1152, the English kingdom was acquired by conquest and was the creation of Henry V.

When he landed a great English army on the beaches of Normandy at the beginning of August 1417 Henry opened up an entirely new phase in the Hundred Years’ War. Never before had an English monarch invaded France with such ambitious plans: nothing less than the wholesale conquest and permanent annexation of Normandy. Yet, after he had achieved this in the space of just two years, the opportunity presented itself to secure a prize to which even his most illustrious ancestor, Edward III, could only aspire: the crown of France itself. On 21 May 1420 Charles VI of France formally betrothed Henry V of England to his daughter and recognised him as his heir and regent of France. In doing so he disinherited his own son and committed both countries to decades of warfare.

By a cruel twist of fate, Henry died just seven weeks before his father-in-law, so it was not the victor of Agincourt but his nine-month- old son, another and much lesser Henry, who became the first (and last) English king of France. Until he came of age and could rule in person, the task of defending his French realm fell to his father’s right-hand men. First and foremost among these was his brother John, duke of Bedford, a committed Francophile who made his home in France and for thirteen years ruled as regent on his nephew’s behalf. His determination to do justice to all, to rise above political faction and, most important of all, to protect the realm by a slow but steady expansion of its borders meant that, at its height, the English kingdom of France extended from the coast of Normandy almost down to the banks of the Loire: to the west it was bounded by Brittany, to the east by the Burgundian dominions, both of which, nominally at least, owed allegiance to the boy-king.

Bedford’s great victory at Verneuil in 1424 seemed to have secured the future of the realm – until the unexpected arrival on the scene of an illiterate seventeen-year-old village girl from the marches of Lorraine who believed she was sent by God to raise the English siege of Orléans, crown the disinherited dauphin as true king of France and drive the English out of his realm. The story of Jehanne d’Arc – better known to the English-speaking world today as Joan of Arc – is perhaps the most enduringly famous of the entire Hundred Years’ War. The fact that, against all the odds, she achieved two of her three aims in her brief career has raised her to iconic status, but it is the manner of her death, burned at the stake in Rouen by the English administration, which has brought her the crown of martyrdom and literally made her a saint in the Roman Catholic calendar. The terrible irony is that Jehanne’s dazzling achievements obscure the fact that they were of little long-term consequence: a ten-year-old Henry VI was crowned king of France just six months after her death and his kingdom endured for another twenty years.

Of far more consequence to the prosperity and longevity of the English kingdom of France was the defection of the ally who had made its existence possible. Philippe, duke of Burgundy, made his peace with Charles VII in 1435, just days after the death of Bedford. In the wake of the Treaty of Arras much of the English kingdom, including its capital, Paris, was swept away by the reunited and resurgent French but the reconquest stalled in the face of dogged resistance from Normandy and brilliant tactical military leadership from the “English Achilles”, John Talbot. For almost a decade it would be a war of attrition between the two ancient enemies, gains by each side compensating for their losses elsewhere, but no decisive actions tipping the balance of power.

Nevertheless, the years of unremitting warfare had their cost, imposing an unsustainable financial burden on England and Normandy, draining both realms of valuable resources, including men of the calibre of the earls of Salisbury and Arundel, who were both killed in action, and devastating the countryside and economy of northern France. The demands for peace became more urgent and increasingly voluble, though it was not until Henry VI came of age that anyone in England had the undisputed authority to make the concessions necessary to achieve a settlement.

The Truce of Tours, purchased by Henry’s marriage to Marguerite of Anjou, the infamous ‘she-wolf of France’, proved to be a disaster for the English. In his determination to procure peace at any price, the foolish young king secretly agreed to give up a substantial part of his inheritance: the county of Maine would return to French hands without compensation for its English settlers who had spent their lives in its defence.

Worse was to follow, for while the English took advantage of the truce to demobilise and cut taxes, Charles VII used it to rearm and reorganise his armies so that, when he found the excuse he needed to declare that the English had broken its terms, he was ready and able to invade with such overwhelming force that he swept all before him. The English kingdom of France which, against the odds, had survived for three decades, was crushed in just twelve months.

#historyedit#litedit#hundred years' war#medieval#english history#french history#european history#history#history books#nanshe's graphics

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Journey to Bosworth: Behind Henry Tudor, the hand of France.

Today we're not talking about a particular figure that was vindicated or wronged at Bosworth field but about a country whose support was important, if not decisive, in the Tudor triumph: France.

France's support for the Tudor cause is a primal example of internal policy shaping the foreign one. During Louis XI's reign (1461-1483), France became more centralized country, destroying many powerful vassal's fiefdoms (Anjou, Burgundy, Armagnac, etc.…). Louis had made plans to incorporate one of the last large feudal demesnes autonomous from royal power: the duchy of Britanny. Britanny had been sometimes an English ally during the Hundred Years War, and it had a very fragile succession as Francis II of Britanny had only two daughters and cousins eager to take their place when he died. The issue was that Louis XI died before and left as ruler thirteen years of Charles VIII under his elder sister, Anne de Beaujeu. Anne wanted to pursue her father's expansionist policy. Still, as a regent, her position was far less secure, and there was a backlash from the nobility against her father's legacy. So France was quite unstable during the beginning of Charles VIII's reign, culminating in the 1485-1488 'Mad War' between the regency and various nobles supported by foreign powers.

The last thing Anne and her councilors wanted was English involvement during the difficult steps of a minority. England had shown itself troublesome in the previous centuries, and their kings still claimed the French crown. They also had an important stronghold in the country with the town of Calais, nearby northern France. Louis XI was very eager to not meddle with England and have it as neutral or as an ally against his enemies. This is why he gave help to the Lancastrians during the 1460s and supported Henry VI's restoration in 1470. He wanted English help against Burgundy, and Lancastrian England did declare war on the duchy prematurely in 1471, before Edward IV's invasion and restoration a few months later.

Failing to make England an ally, Louis XI at least succeeded at buying its neutrality. In 1474, he immediately made his peace with the triumphant Yorkist king in exchange for £10,000 per year and £15,000. He also promised his heir Charles to Elizabeth of York. But their relationship faded soon after. In 1480, England waged war against France's ally Scotland. Louis XI, who finally made his peace with the Burgundian estates in 1482, had no desire to neutralize Edward IV anymore. He stopped paying his pension and broke his son's marriage toward Elizabeth of York in exchange for a much more promising one with Margaret of Burgundy. It was a foreign policy disaster for Edward IV, who lost his Burgundian ally and his compensations for doing so.

1482 was a geopolitical disaster for England, which made Edward IV look like a fool. He made an unpopular peace that looked like he was bribed by England's traditional foe and got fooled by it.

Richard, who was duke of Gloucester by that time, was vindicated. He was the one who argued against peace. When Louis XI made his peace with Edward IV in 1475, he made sure to sustain it by giving pensions to many magnates like Lord Stanley, lord Howard or Lord Hastings. Richard refused to get money from the enemy and returned to the north shortly after, with rumors of tensions between him and his brother. Between 1480 and 1482, he spearheaded the efforts against Scotland, returning Berwick to England after its loss during Henry VI's reign. His prestige was enormous and no doubt played its part in his subsequent usurpation. Richard III had by 1483 the image of the greatest living warrior in England and an uncompromising foe to England's enemies.

When Edward IV died, Louis XI's last days were focused on events across the Channel. No doubt he was happy to see a minority that could neutralize England for many years. But by June, it was clear that his brother Richard would be king and shape his realm's foreign policy. Louis XI saw himself dying in the summer of 1483, and his worst fears were becoming real. It wouldn't be a child king in England closely monitored by the experienced Louis XI, but a bellicist and able king in England facing a frail regency in France.

Thus, Louis XI's last days might have been focused on the English situation. With Burgundy finally cowed and many other French magnates disappeared, London was the biggest threat. And Louis XI himself had broken the Picquigny deal, while Scotland was in no shape to help its French ally (they would have internal strife until James III died in 1488). Louis XI might have died advising his daughter and son-in-law, the future regents, to take care of the English problem first.

Anne would take up the regency and be a dominant figure in French politics. Her first target was Britanny, with an aging duke Francis II with only daughters to succeed. Francis II also had Henry Tudor in his custody. In late 1483, he would support an ill-fated attempt to overthrow Richard III hoping that the Tudor pretender would help Britanny against the regency. Its failure would condemn Francis II's hopes of immediate English help.

Anne de Beaujeu, regent of France, didn't look kindly on those attempts and had no cards to play in this game. She was too busy enforcing the regency and organizing the General Estates (reunion of the representatives of the three orders of France) at Tours in 1484. In short, she was in a fight for the regency against her male cousin and brother-in-law Louis II of Orléans. However, she never lost attention from the English question, as in the Tours General Estates. The chancellor of France, Guillaume de Rochefort, would discuss Edward V's fate compared to their own child-king Charles VIII. French propagandists and servants like Philippe de Commynes or the chancellor of France itself would accuse Richard III of killing his nephews. In short: the French regency was doing everything in its power to slander Richard III in the eyes of the French and continental public. The General Estates of Tours was the first to assemble deputies from the whole kingdom of France and the surest way to make sure those rumors would widely spread.

In September 1484, an opening would create itself for Anne. Henry Tudor would flee the destabilized court of Francis II (one of his councilors tried to sell him to Richard III) and come forward to his cousins of France. There, Anne would welcome him and secure the extradition of his other supporters stuck in Britanny. The Tudor card was now in French hands, and Britanny had now lost control of the English situation.

What did Anne think of the cousin she saw for the first time? They had a common ancestor in Charles VI of France, but familial solidarity was secondary to preserving one's estate and positions. Anne's position as a regent was precarious, and she certainly saw in 1484 the burgeoning of the feudal coalition against her. It was crucial to deter English involvement in the war. Indeed, Henry Tudor might have promised support to Britanny in 1483 in exchange for their help during Buckingham's rebellion. However, Briton's treasurer Pierre Landais did try to sell him to Richard III in exchange for support against France. This might have deterred Henry toward any promises he had made to Britanny in the past, but it was also worrying news for Anne, as it shows that Richard III was more than ready to intervene in France. For Anne de Beaujeu, Henry Tudor was free to ally with France and might be her best pawn against Richard III.

In March 1485, Richard III's wife died. It weakened his position, as rumors were spread accusing Richard III of poisoning his wife to marry his niece, Elizabeth of York. But that was another threat for Anne as Richard III was now free to use his marriage to create an alliance on the international stage. He might have considered Francis II of Brittany's heir, Anne, catastrophic for France. Henry Tudor would finally secure French support indispensable for his expedition.

When he landed at Milford Haven in Wales, Henry Tudor was accompanied by various exiles and opponents of Richard III. Those magnates (Wells, his uncle Jasper, the earl of Oxford) didn't bring many troops with them, and the bulk of the Tudor forces were French (and maybe Scottish) mercenaries led by Philibert de Chandée. Those mercenaries might have been 5,000 but were more probably 2,000 strong. With them, Henry Tudor received from the French king 40,000 Livres tournois for his expenses. Without France, Henry Tudor wouldn't be capable of being a challenge for Richard III. It is not sure if Anne and her allies thought that Henry Tudor would win. However, it would prevent Richard III from interfering in France for a time.

Thus, during 1485, in which Louis of Orleans would try various methods to overthrow the regency, England would not intervene. It was infringed by its internal matters, with Henry Tudor's expedition and ascension to the throne. Anne would succeed at overthrowing a dangerous bellicist king for a king untested in battle. Better, Henry Tudor's hand was promised to Elizabeth of York so that Anne wouldn't fear any dangerous marriage from him.

It's important to note that Henry Tudor wasn't a French puppet. The rumors that Henry VII would surrender Calais to the French in exchange for their help would prove unfounded. Henry VII would also support Britanny's support for independence in 1488, but on a small scale (he sent at best 700 men). His invasion of France in 1492 would be aborted, and Henry VII would resort to Edward IV's policies of getting pensions from France.

What Anne planned to achieve by putting France's weight behind Henry Tudor was, in the short term, to neutralize England. In the long-term, it was to replace Richard III, a dangerous, bellicist king whose anti-french policies were an indication that England might intervene in the continent on a large scale. Contrary to Edward IV or Henry VII, there was every evidence that Richard III wouldn't back down in exchange for cash. Bosworth was, indirectly, a French victory, which is deeply ironic as it marks for some the end of the French era.

If Richard III won at Bosworth, we might have looked at a whole different timeline. Richard might have sought revenge on France and court Anne of Britanny's hand. We could look at an alternative timeline in which Richard III land in Britanny, marry the heiress, and wage war against the regency.

#henry vii of england#richard iii#anne de beaujeu#war of the roses#mad war#French involvment in the war of the roses#ending the french-norman era with french troops#Journey to Bosworth

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Philippe I, Duc d'Orléans (Philippe de France)

Philippe I, duc d'Orléans was born on September 21, 1640 in Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France. His parents were King Louis XIII [1601-1643] and Queen Anne of Austria [1601-1666]. He had one elder brother, King Louis XIV [1638-1715].

In 1661 he married Henrietta Anne of England [1644-1670]. Together they had four [4] children: Marie Louise d'Orléans [1662-1689], Philippe Charles d'Orléans, Duc de Valois [1664-1666], stillborn daughter [July 09, 1665], and Anne Marie d'Orléans [1669-1728]. After Henrietta's death, Philippe married Princess Elisabeth Charlotte of the Palatinate [1652-1722] in 1671. Together they had three [3] children: Alexandre Louis d'Orléans, Duc de Valois [1673-1676], Philippe II, Duc d'Orléans [1674-1723] and Élisabeth Charlotte d'Orléans [1676-1744].

Philippe was styled the Duke of Anjou from birth. He became the Duc d'Orléans in 1660 after the death of his Uncle Gaston. In 1661 he also received the dukedoms of Valois and Chartres, and the lordship of Montargis. Following his victory in battle in 1671, Louis XIV gave him the dukedom of Nemours, the marquisates of Coucy and Folembray, and the countships of Dourdan and Romorantin. Upon the death of Mademoiselle in 1693, Philippe acquired the dukedoms of Montpensier, Châtellerault, Saint-Fargeau and Beaupréau. He also became the prince of Joinville, Count of Mortain, Bar-sur-Seine, and Viscount of Auge and Domfront. Philippe was also given the nickname of "the grandfather of Europe."

He was a successful military commander during the War of Devolution in 1667. In 1676 and 1677 he took part in the sieges in Flanders, and was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant General. The most impressive victory won under Philippe's command took place on April 11, 1677: the Battle of Cassel against William III, Prince of Orange.

Philippe de France died on June 09, 1701 (aged 60) in Château de Saint-Cloud, France. The cause of death was from a fatal stroke. He was laid to rest on June 21, 1701 at the Basilica of Saint-Denis, France

#french history#history#royalty#personal life#philippe i duke of orléans#philippe of france#duc d'orléans#duke of orleans#philippe I#titles#military#world history

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Battle of Almansa

During the War of Spanish Succession (1701-1714), fought by several European powers after the King of Spain Charles II died childless (and with him, the Habsburgs of Spain), France, with Castile & Leon, the Duchy of Mantoue, and the Electorates of Bavaria and Cologne opposed the Holy Roman Empire, Austria, Prussia, Great Britain, Savoie, the United Provinces, Portugal, Aragon, and the Camisards.

Louis XIV fought his last great war to put his grandson, Philippe, Duke of Anjou, on the throne of Spain (Spain’s succession rules do not exclude women, and Philippe was a grandson of Infanta Maria Teresa) and to break the centuries old encircling of France by the Habsburg powers.

In 1707, on April 25, in Almansa, a Franco-Spanish army led by the Duke of Berwick (Jacques I Fitz James, illegitimate son of James II Stuart, born in France) beats Dutch, Portuguese and British troops of Archduke Charles led by Henri de Massue and Antonio Luis de Sousa.

It has been said that Almansa was “probably the only battle in History where British troops were led by a Frenchman, and French troops by a British.”

The victory of Almansa was not the end of the war, but allowed Philippe V to recover his throne.

Its memory is persisting in Spain. On Youtube or Tumblr you can find videos of historical reenactments.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The order of the Knights of the Holy Spirit

(l'Ordre des Chevaliers du Saint Esprit).

Louis XIV hearing the oath taken by Philippe, Duke of Anjou, in 1654 (by Philippe de Champaigne).

The Order of the Holy Spirit (i.e. "l'Ordre du Saint Esprit") was a French order of chivalry founded by Henri III in 1578.

Prior to the creation of the Order of the Holy Spirit in 1578 by King Henri III, the senior order of chivalry in France had been the Order of Saint Michael (Saint Michel).This order was originally created in 1469 to help ensure that leading French nobles remained loyal to the Crown (basically the "King's Club") Its membership was initially restricted to a small number of powerful princes and nobles, but this increased dramatically due to the pressures of the Wars of Religion.

At the beginning of the reign of Henry III, the Order of Saint Michel had several hundred living members, ranging from kings to bourgeois. Recognising that the order had been significantly devalued, Henry III founded the Order of the Holy Spirit on December 31, 1578, thereby creating a two-tier system: the new order would be reserved for princes and powerful nobles, whilst the Order of Saint Michel would be for less eminent servants of the Crown. The new order was dedicated to the Holy Spirit to commemorate the fact that Henry III was elected as King of Poland (1573) and inherited the throne of France (1574) on two pentecosts.

Collar of the Order.

The King of France was the Sovereign and Grand Master (Souverain Grand Maître), and he made all appointments to the order. Members of the order can be split into three categories:

8 Ecclesiastic members;

4 Officers;

100 Knights.

Initially, four of the ecclesiastic members had to be cardinals, whilst the other four had to be archbishops or prelates. This was later relaxed so that all eight had to be either cardinals, archbishops or prelates.

Members of the order had to be Roman Catholic and had to be able to demonstrate three (originally four) degrees of nobility. The minimum age for members was 35, although there were some exceptions:

Children of the king were members from birth, but they weren't received into the order until they were 12;

Princes of the Blood could be admitted to the order from the age of 16;

Foreign royalty could be admitted to the order from the age of 25.

All knights of the order were also members of the Order of Saint Michel. As such, they were generally known by the term Chevalier des Ordres du Roi (i.e."Knight of the Royal Orders"), instead of the more lengthy Chevalier de Saint-Michel et Chevalier du Saint-Esprit (i.e."Knight of Saint Michel and Knight of the Holy Spirit").

_______________

The order had its own officers. They were responsible for the ceremonies and the administration of the order.

Officers of the order were as follows:

Chancellor;

Provost and Master of Ceremonies;

Treasurer;

Clerk (greffier).

Jean-Baptiste Colbert as a treasurer of the Order of the Holy Spirit (by Claude Lefebvre).

Under the reign of Louis XIV, the King became the unique decision- maker (the new members were elected collectively until then). Louis used the Order as a political tool and therefore, rewarded his subjects for their loyalty and their military worth.

The symbol of the order is known as the Cross of the Holy Spirit (this is a Maltese Cross). At the periphery, the eight points of the cross are rounded, and between each pair of arms there is a Fleur-de-Lys. Imposed on the centre of the cross is a dove. The eight rounded corners represent the Beatitudes, the four fleur-de-lys represent the Gospels, the twelve petals represent the Apostles, and the dove signifies the Holy Spirit. The Cross of the Holy Spirit was worn hung from a blue riband ("Le cordon bleu").

In France, red or green sealing wax used for the royal seal on documents requiring a royal seal. Only in documents relating to the Order of the Holy Spirit was white wax used for this royal seal.

_________________

Louis XIV received the collar of the Order on june 8, 1654 at Reims, one day after his consecration. He is the 4th Sovereign and Grand Master of the Order.

Philippe, Duke of Anjou, received the title on the same day. His son Philippe received it in 1686.

Philippe de Lorraine was awarded, along with his brothers Louis and Charles, on december 31, 1688 at Versailles.

Philippe d'Orléans wearing the Blue Riband.

Aannd extra

#chivalry#order of the holy spirit#ordre du saint esprit#ordre de saint-michel#louis xiv#philippe d'orleans#chevalier de lorraine#long post#txt post#versailles

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Committee of300 Abdullah II King of Jordan Roman Abramovich Josef Ackermann Edward Adeane Marcus Agius Martti Ahtisaari Daniel Akerson Albert II King of Belgium Alexander Crown Prince of Yugoslavia Giuliano Amato Carl A. Anderson Giulio Andreotti Andrew Duke of York Anne Princess Royal Nick Anstee Timothy Garton Ash William Waldorf Astor Pyotr Aven Jan Peter Balkenende Steve Ballmer Ed Balls Jose Manuel Barroso Beatrix Queen of the Netherlands Marek Belka C. Fred Bergsten Silvio Berlusconi Ben Bernanke Nils Bernstein Donald Berwick Carl Bildt Sir Winfried Bischoff Tony Blair Lloyd Blankfein Leonard Blavatnik Michael Bloomberg Frits Bolkestein Hassanal Bolkiah Michael C Bonello Emma Bonino David L. Boren Borwin Duke of Mecklenburg Charles Bronfman Edgar Jr. Bronfman John Bruton Zbigniew Brzezinski Robin Budenberg Warren Buffett George HW Bush David Cameron Camilla Duchess of Cornwall Fernando Henrique Cardoso Peter Carington Carl XVI Gustaf King of Sweden Carlos Duke of Parma Mark Carney Cynthia Carroll Jaime Caruana Sir William Castell Anson Chan Margaret Chan Norman Chan Charles Prince of Wales Richard Chartres Stefano Delle Chiaie Dr John Chipman Patokh Chodiev Christoph Prince of Schleswig-Holstein Fabrizio Cicchitto Wesley Clark Kenneth Clarke Nick Clegg Bill Clinton Abby Joseph Cohen Ronald Cohen Gary Cohn Marcantonio Colonna di Paliano Duke of Paliano Marcantonio Colonna di Paliano Duke of Paliano Constantijn Prince of the Netherlands Constantine II King of Greece David Cooksey Brian Cowen Sir John Craven Andrew Crockett Uri Dadush Tony D'Aloisio Alistair Darling Sir Howard Davies Etienne Davignon David Davis Benjamin de Rothschild David Rene de Rothschild Evelyn de Rothschild Leopold de Rothschild Joseph Deiss Oleg Deripaska Michael Dobson Mario Draghi Jan Du Plessis William C. Dudley Wim Duisenberg Edward Duke of Kent Edward Earl of Wessex Elizabeth II Queen of the United Kingdom John Elkann Vittorio Emanuele Prince of Naples Ernst August Prince of Hanover Martin Feldstein Matthew Festing François Fillon Heinz Fischer Joschka Fischer Stanley Fischer Niall FitzGerald Franz Duke of Bavaria Mikhail Fridman Friso Prince of Orange-Nassau Bill Gates Christopher Geidt Timothy Geithner Georg Friedrich Prince of Prussia Dr Chris Gibson-Smith Mikhail Gorbachev Al Gore Allan Gotlieb Stephen Green Alan Greenspan Gerald Grosvenor 6th Duke of Westminster Jose Angel Gurria William Hague Sir Philip Hampton Hans-Adam II Prince of Liechtenstein Harald V King of Norway Stephen Harper François Heisbourg Henri Grand Duke of Luxembourg Philipp Hildebrand Carla Anderson Hills Richard Holbrooke Patrick Honohan Alan Howard Alijan Ibragimov Stefan Ingves Walter Isaacson Juan Carlos King of Spain Kenneth M. Jacobs DeAnne Julius Jean-Claude Juncker Peter Kenen John Kerry Mervyn King Glenys Kinnock Henry Kissinger Malcolm Knight William H. Koon II Paul Krugman John Kufuor Giovanni Lajolo Anthony Lake Richard Lambert Pascal Lamy Jean-Pierre Landau Timothy Laurence Arthur Levitt Michael Levy Joe Lieberman Ian Livingston Lee Hsien Loong Lorenz of Belgium Glenys Kinnock Henry Kissinger Malcolm Knight William H. Koon II Paul Krugman John Kufuor Giovanni Lajolo Anthony Lake Richard Lambert Pascal Lamy Jean-Pierre Landau Timothy Laurence James Leigh-Pemberton Leka Crown Prince of Albania Mark Leonard Peter Levene Lev Leviev Arthur Levitt Michael Levy Joe Lieberman Ian Livingston Lee Hsien Loong Lorenz of Belgium Archduke of Austria-Este Louis Alphonse Duke of Anjou Gerard Louis-Dreyfus Mabel Princess of Orange-Nassau Peter Mandelson Sir David Manning Margherita Archduchess of Austria-Este Margrethe II Queen of Denmark Guillermo Ortiz Martinez Alexander Mashkevitch Stefano Massimo Prince of Roccasecca dei Volsci Fabrizio Massimo-Brancaccio Prince of Arsoli and Triggiano William Joseph McDonough Mack McLarty Yves Mersch Michael Prince of Kent Michael King of Romania David Miliband Ed Miliband Lakshmi Mittal Glen Moreno Moritz Prince and Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel Rupert Murdoch Charles Napoleon Jacques Nasser Robin Niblett Vincent Nichols Adolfo Nicolas Christian Noyer Sammy Ofer Alexandra Ogilvy Lady Ogilvy David Ogilvy 13th Earl of Airlie Jorma Ollila Nicky Oppenheimer George Osborne Frederic Oudea Sir John Parker Chris Patten Michel Pebereau Gareth Penny Shimon Peres Philip Duke of Edinburgh Dom Duarte Pio Duke of Braganza Karl Otto Pohl Colin Powell Mikhail Prokhorov Guy Quaden Anders Fogh Rasmussen Joseph Alois Ratzinger (Pope Benedict XVI) David Reuben Simon Reuben William R. Rhodes Susan Rice Richard Duke of Gloucester Sir Malcolm Rifkind Sir John Ritblat Stephen S. Roach Mary Robinson David Rockefeller Jr. David Rockefeller Sr. Nicholas Rockefeller Javier Echevarria Rodriguez Kenneth Rogoff Jean-Pierre Roth Jacob Rothschild David Rubenstein Robert Rubin Francesco Ruspoli 10th Prince of Cerveteri Joseph Safra Moises Safra Peter Sands Nicolas Sarkozy Isaac Sassoon James Sassoon Sir Robert John Sawers Marjorie Scardino Klaus Schwab Karel Schwarzenberg Stephen A. Schwarzman Sidney Shapiro Nigel Sheinwald Sigismund Grand Duke of Tuscany Archduke of Austria Simeon of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha Olympia Snowe Sofia Queen of Spain George Soros Arlen Specter Ernest Stern Dennis Stevenson Tom Steyer Joseph Stiglitz Dominique Strauss-Kahn Jack Straw Peter Sutherland Mary Tanner Ettore Gotti Tedeschi Mark Thompson Dr. James Thomson Hans Tietmeyer Jean-Claude Trichet Paul Tucker Herman Van Rompuy Alvaro Uribe Velez Alfons Verplaetse Kaspar Villiger Maria Vladimirovna Grand Duchess of Russia Paul Volcker Otto von Habsburg Hassanal Bolkiah Mu'izzaddin Waddaulah Sultan of Brunei Sir David Walker Jacob Wallenberg John Walsh Max Warburg Axel Alfred Weber Michael David Weill Nout Wellink Marina von Neumann Whitman Willem-Alexander Prince of Orange William Prince of Wales Dr Rowan Williams Shirley Williams David Wilson James Wolfensohn Neal S. Wolin Harry Woolf R. James Jr. Woolsey Sir Robert Worcester Sarah Wu Robert Zoellick Most of the names listed above are of Jewish lineage

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The French Royal Family: Titles and Customs

Petit-Fils, Petite-Fille de France

“In the 1630s, a lower rank was created, namely petit-fils, petite-fille de France, for the children of the younger sons of a sovereign. This was designed for Anne-Marie-Louise d'Orléans, duchess of Montpensier, daughter of Gaston d'Orléans, at a time when the king Louis XIII had no children and his brother Gaston (heir presumptive) had only one daughter. The petits-enfants de France ranked after the enfants de France but before all other princes of the blood.

Collectively, the enfants de France and petits-enfants de France formed the Royal family.”

Princes du Sang

“In France, aside from a few exceptions, prince was not a title, but a rank that denoted dynasts, i.e., individuals with an eventual succession right to the throne. The word, and its connotation of sovereignty, was felt to be their preserve. Collectively known as the Princes du Sang (less often princes du sang de France, princes des lys) they were, in theory, all descendents in legitimate male line of a French sovereign outside of the royal family itself. The term dates from the 14th century. The princes of the blood all had a seat at the Conseil du Roi, or Royal Council, and at the Paris Parlement.

In the 17th and 18th centuries it became customary to restrict the term of prince du sang to those dynasts who were not members of the Royal family, i.e. children or grandchildren in male line of the sovereign, since those became known as the enfants and petits-enfants de France.

Kings were somewhat selective in their choice of who was treated as prince of the blood.”

Premier Prince du Sang

“Ranking among the princes du sang was by order of succession rights. The closest to the throne (excluding any fils de France) was called Premier Prince du Sang. In practice, it was not always clear who was entitled to the rank, and it often took a specific act of the king to make the determination.

As the first two were members of the Royal Family and thus outranked other princes of the blood, it was felt that the rank would not honor them enough, and the deceased's son Louis de Bourbon-Condé took the rank, although the duc de Chartres drew the pension (the source for this is Sainctot, cited in Rousset de Missy).

On the death of Louis de Bourbon-Condé in 1709 the title would have passed to the duc d'Orléans, nephew of Louis XIV, but he did not use it (he did, however, call himself first prince of the blood on occasion.) After the duc d'Orléans's death in December 1723, his son officially received the title. It remained to the head of the Orléans family until 1830. However, at the death of the duc d'Orléans in 1785, it was decided that, once again, the duc d'Angoulême, son of the king's brother, ranked too high for the title, and it was granted to the new duc d'Orléans (letters patent of 27 Nov 1785); but Louis XVI decided that the duc d'Orléans would hold the title until the duc d'Angoulême had a son who could bear it.

The rank of "premier prince du sang" was not purely a court title or a precedence. It carried with it legal privileges, notably the right to have a household (maison), such as the king, the queen, and the enfants de France each did. A household was a collection of officers and employees, paid for out of the State's revenues, and constituted a miniature version of the royal administration, with military and civil officers, a council with a chancelor and secretaries, gentlemen-in-waiting, equerries, falconers, barbers and surgeons, a chapel, etc.”

Styles and Precedence of the Princes du Sang

Precedence

“Until the 15th century, precedence among princes of the blood, or even between them and other lords, depended on the title... [A]n edict of 1576 set that princes of the blood would have precedence over all lords, and between them by order in the line of succession rather than by their titles.

Precedence was set according to the following rules (Guyot, loc. cit., vol. 2, p. 382; he is in fact citing Rousset de Missy, who is himself citing Sainctot Sr., who was introducteur des ambassadeurs under Louis XIV).

All princes of the blood were divided into:

children of the current sovereign and children of his eldest son,

children of the previous sovereign and children of his eldest son,

all others.

The first two categories formed the royal family (Guyot says children and grandchildren, but I [original author] interpret his words strictly).

Precedence was set:

by category (i.e., anyone of category 1 outranked anyone of category 2)

within category:

between males, according to the order in the line of succession,

between males and females, according to the right of succession (that is, males before females),

between females, according to the degree of kinship with the king.

Thus the son of the Dauphin outranked the king's brother or younger son, but the daughter of a Dauphin was outranked by the king's daughter; the king's daughter in turn outranked the king's brother or sister. Wives took the rank of their husbands, so a Dauphin outranked a king's sister.

Another illustration of these rules is found in the listing of French princes and princesses in the Almanach Royal of 1789, a semi-official directory of the French state (see p. 33 and p. 34). The order is:

the king and the queen

the king's two sons (group 1, males)

the king's daughter (group 1, females)

the king's brothers and their wives (group 2, males)

the king's sisters (group 2, females)

the king's aunts (group 2, females)

the children of the king's younger brother (group 3)

the Orléans branch, males followed by females

the Bourbon-Condé branch, males followed by females

the Bourbon-Conti branch, males followed by females