#pedro albizu campos

Text

Happy birthday, Pedro Albizu Campos! (September 12, 1891)

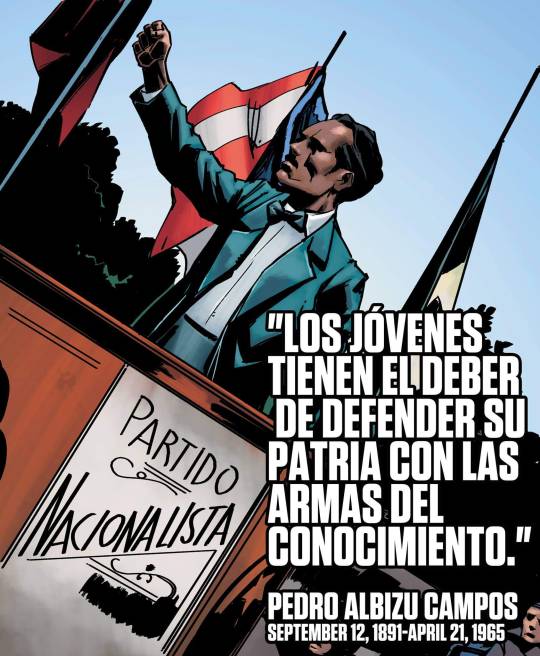

Popularly known as "El Maestro" in Puerto Rico, Pedro Albizu Campos was born in the municipality of Ponce to a Black domestic worker and a Basque merchant. He enlisted in the United States Army during World War I, and his experiences with racism in the Army forever changed him. Albizu became active in the movement for Puerto Rican independence, associating with leaders of independence leaders in countries such as India and Ireland. Becoming the leader of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party in 1930, Albizu oriented the party in an aggressive and confrontational direction. Albizu was arrested multiple times and weathered assassination attempts even as he prepared for the inevitability of armed struggle to liberate Puerto Rico. After one of these arrests, while in prison, Albizu's health deteriorated and he effectively wasted away before his death in 1965. He maintained that his decaying health was the result of radiation experiments being conducted on him without his consent.

“A people full of courage and dignity cannot be conquered by any imperialism.”

172 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Documentary , Albizu The Movie, ( King of the Towels)

#youtube#Albizu The Movie#puerto rico#pedro albizu campos#documentary about Pedro Albizu Campos#yo soy boricua pa'que tu lo sepas!#documental de Pedro Albizu Campos#puertorriqueños#boricuas#puerto ricans#grandes puertorriqueños#educate boricua#todo lo bueno de puerto rico

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

We are not small, it's just that we are on our knees.

-Pedro Albizu Campos

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Puerto Rico is back in the news. The island territory – where US citizens do not get to vote for the president nor send a voting representative to Congress – is planning a binding referendum on whether to become a US state, or whether to secede from the USA altogether.

- "War Against All Puerto Ricans", Pluralistic, Cory Doctorow

#puerto rico#puerto rican independence#puerto rican statehood#secession#cory doctorow#pluralistic#Pedro Albizu Campos

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Historia vasca en Puerto Rico | Alejandro Albizu y Romero "El Vizcaino", (1844-1920) padre de Pedro Albizu Campos. Albizu Campos era hijo de padre vasco de familia campesina y terrateniente.

#Historia vasca en Puerto Rico#Alejandro Albizu#pedro albizu campos#puertorriqueños#boricuas#puerto rico#latinos#españa#boricuasporelmundo#Esto es PR#Esto es Puerto Rico#vascos

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

La sabiduría de Albizu Campos trasciende a 125 años de la invasión estadounidense

Dr. PEDRO ALBIZU CAMPOS

Publicado por Partido Nacionalista

“Puerto Rico está resurrecto. El pueblo se levanta para imponer su derecho a la vida.

En Puerto Rico se decidirá si en América ha de triunfar la fuerza del derecho o el derecho de la fuerza.

Grande es el imperio que desafiamos, pero más grande que ese imperio es nuestro derecho a la Libertad.

Puerto Rico no puede colocar su Derecho a la…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

A very dear friend sent me this ... only one correction: PUERTO Rico!! --"Mayaguez, P. R., March 24, 1926." -- and the struggle continues to this day!!!

My country!! ... the struggle has never ended!!

#dr rex equality news information education#graphic source#graphics#graphic#hortyrex ©#horty#quote#it is what it is#puerto rico#oldest colony#usa#American colony#Don Pedro#Albizu Campos#independence

0 notes

Text

Puerto Rico x Ireland

very quick doodle.

Version where Ireland has no freckles and a fun fact (excuses as to why I ship them)

Did you know that a Puerto Rican man,

Pedro Albizu Campos

(this man)

helped with the Irish constitution?

Here's the wiki article that talks about him:

#Cooking something historical but in the meantime have this#I wish I had drawn them better but I'm not feeling too good rn#Also also#PR is still a wip so their design may change in the future#Idk even know their gender#They/them Puerto Rico when/j#Hetalia#Hetalia oc#My oc#Ship tag#Aph oc#Hws oc#Hetalia Puerto Rico#Hws Puerto Rico#Aph Puerto Rico#hetalia ireland#aph ireland#Hws Ireland#My art

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

By Sharon Black

Berta Joubert-Ceci, a convenor of the 2019 Puerto Rico International Tribunal of Colonial Crimes of the United States, will be touring U.S. cities in April to highlight conditions inside Puerto Rico and report on the struggle against colonialism on the island. She will present slides, visuals, and video documentation.

#Berta Joubert-Ceci#speaking tour#Puerto Rico#privatization#gentrification#imperialism#climate crisis#racism#repression#colonialism#Struggle La Lucha

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the middle of the 20th century, one woman became the face of the movement for Puerto Rican self-determination. Her name was Lolita Lebrón, and in an effort to draw the world's attention to Puerto Rico's colonial subjugation by the United States, she and a handful of men opened fire in the U.S. House of Representatives.

After the United States Capitol was stormed by insurrectionists on January 6th, 2021, Amarilis Rodriguez questioned how long the domestic terrorists would serve in prison, considering that Lebrón and her fellow pro-independence activists served 25 years (after being sentenced to even more.) Will the United States legal system punish insurrection as harshly as it punishes anti-colonialism?

Although Puerto Rico remains a US territory today, the independence movement that Lebrón was a part of has never disappeared. Lolita Lebrón and her collaborators expected to die in the attack, and although five congressmen were wounded, they claimed that they had never intended to kill anyone. This is the story of the 1954 attack on the Capitol and the woman who led it.

Who was Lolita Lebrón?

Lightfoot/Getty Images

Born on November 19th, 1919, Dolores "Lolita" Lebrón Sotomayor was the fifth and final child of a financially insecure family living in Lares, Puerto Rico. Her father tragically died at the age of 42, when Lebrón was a teenager, due to an inability to access sufficient medical care, and their financial situation only worsened afterwards.

Although she may have had some nationalist ideas, during her youth she didn't keep up with politics or activism. But according to Latinas in the United States, although Lebrón didn't take "much notice of Puerto Rico's political situation" while she was growing up, after moving to New York City, she joined the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party chapter in the early 1940s.

However, one event that is said to have resonated with Lebrón was the Ponce Massacre of 1937, where, according to the Zinn Education Project, 19 Nationalists were massacred by the police and over 200 others were wounded. The Guardian claims that the event "radicalized" Lebrón, but she never explicitly said that herself. Lebrón even claimed that she only ended up knowing about the massacre "because someone came to our house who had lost a relative in it. I had heard about a man named Pedro Albizu Campos but I never knew him personally."

The United States and Puerto Rico

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Before the Spanish colonized Puerto Rico, the island was inhabited by the Taíno, who were a subset of the Arawak people. But after the Spanish invaded in the 15th century, they ended up subjugating the island for almost 300 years. Then in the 1800s, according to National Geographic, the people of Puerto Rico started advocating for self-determination and self-governance.

Although the Spanish ended up allowing the island relatively more autonomy, the United States invaded Puerto Rico on July 25, 1898 during the Spanish-American War. And in the subsequent peace treaty, signed December 1898, the Spanish gave the colony to the United States. According to Boricua Power, almost as soon as the United States took control of Puerto Rico, they started encouraging people from the island to emigrate to the United States, Hawaii, Cuba, and Santo Domingo. The United States government pushed the perception that Puerto Ricans were "a good source of labor," though often the jobs that Puerto Ricans traveled to pursue "didn't live up to expectations and promises."

Puerto Rican people who'd emigrated frequently protested their unjust working conditions and the devaluation of their labor. However, even cigar makers in New York City, which was an industry that was "the highest-paid, best organized, [and] most independent," found its work rendered "obsolete, unemployed, and poor" by the tobacco employers. During this entire time, Puerto Ricans continued to demand the right to self-governance.

The Gag Law and the Smith Act

Fox Photos/Getty Images

Meanwhile, on the island itself, the United States sought to suppress any and all nationalistic and pro-independence activity. On June 11, 1948, Jesús T. Piñero, a Puerto Rican man appointed governor by the United States, signed a bill into law that would become known as the Ley de la Mordaza, or the Gag Law.

According to War Against All Puerto Ricans, Law 53, as it was known in the legislation, was entirely intended to disrupt the Puerto Rican independence movement. It made it illegal to speak in favor of independence, write in favor of independence, sing a patriotic tune, or even display the Puerto Rican flag, per Mother Jones. The penalty for breaking this law was a fine of $10,000 and/or 10 years' imprisonment. And when the Puerto Rico colonial government adopted the pro-independence flag in 1952, they changed the blue color on the flag to make it more similar to the United States flag, nullifying the flag's symbolism, "whether intended or not."

Some also referred to the Gag Law as "the Little Smith Act" since it resembled the Smith Act from the mainland United States, which had been intended to suppress communist movements. A big component of both of these Acts made it a felony to "advocate for the violent overthrow of the government" or to be associated with such an organization.

The 1950 uprisings in Puerto Rico

Rosskam/Getty Images

Over the course of four days in 1950, there were several uprisings in Puerto Rico that were led and organized by Pedro Albizu Campos, the president of the Nationalist Party. Along with staging uprisings in eight different towns (Arecibo, Jayuya, Mayagüez, Naranjito, Peñuelas, Ponce, San Juan, and Utado), there were attempts to assassinate both Governor Luis Muñoz Marín of Puerto Rico and President Harry S. Truman of the United States.

According to Introduction to Latino Politics in the U.S., the nationalist groups carried the Puerto Rican flag around and in turn were "attacked by U.S. bomber planes from the air and by U.S. artillery on the ground." Oscar Collazo and Griselio Torresola, who were living in the United States, made an unsuccessful attempt to assassinate President Truman at Blair House on November 1st, 1950. In response to the uprisings, President Truman allowed Puerto Rico to hold a referendum over the creation of a new constitution. After it passed, the new constitution was implemented by July 1952.

According to the Encyclopedia of Activism and Social Justice, Albizu Campos was caught and sentenced to 80 years imprisonment the following year. Although he was pardoned two years later by the governor he tried to assassinate, the pardon was revoked after Lolita Lebrón's attack on the U.S. House of Representatives in 1954.

Lolita Lebrón moves to New York City

Orlando/Getty Images

In the 1940s, Lolita Lebrón moved to New York City and found it difficult to find work. Although she was able to be hired as a seamstress several times, whenever she confronted the discrimination against Puerto Ricans, she was fired. According to Lebrón herself, "After three days of looking for work, getting lost in the trains, walking in the snow, without money for lunch or shelter, I had to deny that I was Puerto Rican in order to have a job."

In response to the prejudice and racism she experienced, Lebrón joined the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party in 1946 and started promoting both feminist and socialist values within the organization. According to Latina, she soon became incredibly influential in the organization and was promoted to top positions like executive delegate and vice president.

Albizu Campos was the party's president and Lebrón had learned everything she could about its founder. According to The Guardian, the two began to correspond as Lebrón took on more and more responsibility within the organization. And in 1954, Lebrón was asked by Albizu Campos to come up with "strategic targets" for an attack. Lebrón chose the United States Congress as their target.

Deciding to attack Washington, D.C.

Shutterstock

In the new constitution of Puerto Rico, the official name of the island was made Estado Libre Asociado, or Commonwealth of the United States. According to Women on the Edge: Ethnicity and Gender in Short Stories by American Women, although this allowed people in Puerto Rico to elect local political officials, the description of "commonwealth" was "an ambiguous political designation" that kept the island "situated within American politics."

According to CENTRO Journal, as with the Guyana Uprising, the attack on the United States government wasn't "so much an attempt to seize power as it was 'a supreme act of protest to attract the attention of the world to the cause of Puerto Rico's independence.'" The ultimate goal was always to throw off the colonialist yoke, but even the note found in Lolita Lebrón's purse after the attack stated that the attack was "aimed at making the Puerto Rican plea heard throughout the world, as no one seemed to pay attention to the sufferings of her people." She reiterated this statement years later from prison, stating, "Attacking the U.S. in its own heart, its own entrails, was Puerto Rico's last recourse... because the island could not arm itself... and confront the U.S. in a traditional war. We made our war the only way we're able to."

Lolita Lebrón recruited Irving Flores, Rafael Cancel Miranda, and Andres Figueroa Cordero for the mission and on March 1st, 1954, they set out for Washington, D.C.

'¡Que Viva Puerto Rico Libre!'

Peter Keegan/Getty Images

On the day that Lebrón, Flores, Cancel Miranda, and Figueroa Cordero traveled from New York City to Washington, D.C. and entered the United States House of Representatives, there were two imperialist topics on the agenda. According to The Young Lords, Puerto Rico was one of the topics, and the other was the Chamizal district between Mexico and Texas, which the United States government didn't want to give back to the Mexican government.

The group waited in the visitor's gallery, and around noon, Lebrón shouted, "¡Que Viva Puerto Rico Libre!" and opened up the Puerto Rican nationalist flag. They all opened fire, firing both into the ceiling and the House floor. Five congressmen were wounded, although no one died in the attack. According to Latina, they had "no intentions of murdering anyone during their attack. Rather, they had prepared to die in their struggle for liberation."

When they were captured, Lolita Lebrón insisted that the men weren't responsible for the attack and that she was the sole instigator, but they were all given lengthy sentences.

And although The Guardian notes "Extraordinary as it seems today, the four Puerto Rican radicals had no difficulty in entering the visitors' gallery of the House of Representatives armed with their Lugers," it was revealed in the attempted coup of 2021 that maybe it's not actually that extraordinary.

Lolita Lebrón's capture and trial

Shutterstock

Lolita Lebrón and her fellow nationalists were captured almost immediately, although one was able to escape briefly before being apprehended. The trial started three months later, lasted 12 days, and on June 16th, 1954, they were all found guilty. According to The New York Times, while Cancel Miranda, Figueroa Cordero, and Flores were sentenced to 25 to 75 years in prison, Lebrón was sentenced to only 16 to 50 years. Since Lebrón had fired at the ceiling rather than the House floor, she was cleared of "assault with intent to kill," which is why she had a lesser sentence.

Although the defense counsel attempted to bring up the question of the nationalist's sanity, even claiming that the "appellants' adherence to an organized minority group in Puerto Rico is said to indicate irrationality," the defendants actively refused an insanity defense. Per the Washington Post, during her trial, Lebrón insisted that she was "being crucified for the freedom of my country." In another trial, an additional six years were added to all the shooters' sentences for "seditious conspiracy."

Lebrón also lost her 12-year-old son during the trial, although no one knew until she was testifying on the stand, and she recounted "what her life had been like with her child and the meaning of his loss."

Continuing to protest in prison

Shutterstock

Lolita Lebrón was imprisoned at the Federal Correctional Institution for Women in Alderson, West Virginia. According to Latinas in the United States, most of her time in prison was spent writing poetry, praying, sewing uniforms, and advocating for the rights of those imprisoned alongside her.

Helping organize a number of hunger strikes in the prison, Lebrón was furious that "women were intimidated and placed in isolation just to keep them in line." She also "refused to accept the validity of her conviction" and refused to apply for parole unless her fellow nationalists were also going to be freed. Insisting that she wouldn't leave prison for anything less than a presidential pardon, she devoted herself to her religion.

In 1978, Assata Shakur was transferred to Alderson and the two political prisoners crossed paths. They knew of the other's activism and admired one another, and at the moment they met there was an outburst of joy in a traditionally austere place. As their eyes recognized one another in the middle of prison, they called out the other's name in happiness and "hugged and kissed each other." It was an auspicious meeting, since the following year both Shakur and Lebrón left prison, one by escape and the other by pardon, respectively.

President Carter commutes Lolita Lebrón's sentence

Fox Photos/Getty Images

In 1978, President Jimmy Carter started reviewing the cases of the nationalists and pardoned Figueroa Cordero first since he had been diagnosed with cancer. The following year, President Carter also commuted the sentences of Lebrón, Flores, and Cancel Miranda after they had been imprisoned for 25 years.

Although some claim that this pardon came out of the pressure from political circles, academics, and the Catholic Church in Puerto Rico, the Washington Post claims that the pardon was "widely suspected to have been part of a prisoner swap to release CIA agents jailed in Cuba." However, according to Women of Color, in Solidarity, the governor of Puerto Rico at the time, Carlos Romero Barceló, was against the pardon because he claimed that it would "encourage terrorism and undermine public safety."

Although Lolita Lebrón was initially treated as a heroine when she was released from imprisonment, some of her followers abandoned her when they became aware of "her pacifist views and her devotion to the Catholic faith." In her autobiography, Shakur also notes how "anticommunist and antisocialist" Lebrón was at the time of their meeting.

Lolita Lebrón's continued activism

Gerald Lopez-cepero/Getty Images

Out of prison, Lolita Lebrón continued her activism for Puerto Rico's self-determination. According to The Guardian, although she recognized the economic benefits of living under American colonial rule, Lebrón "regarded freedom from foreign interference as more important than material well being."

In 2001, Lebrón was arrested twice during the struggle to remove the U.S. Navy from the island of Vieques, which it was using as a bombing range. She was 81-years-old at the time, and although she served 60 days at one point, their protests were ultimately successful.

According to Radical Women, on March 8th, 2008, she led a protest demanding for Puerto Rico's right to self-determination, saying, "We want everyone to know that in Puerto Rico, we women are fighting for our rights as workers, we are fighting for a healthy environment, for poor and marginalized communities, for the freedom of the political prisoners, the well-being of children, for peace, for the defense of our culture and all the rights they intend to take from us."

The end of Lolita Lebrón's life and her legacy

Kevin Hagen/Getty Images

On August 1st, 2010, Lolita Lebrón died as a result of a respiratory disease. But according to Latina, her legacy continues to be celebrated amongst Puerto Ricans. Her portrait is illustrated in murals across Puerto Rico as well as in neighborhoods in Chicago and New York. According to Maria de Lourdes Santiago, a member of the Puerto Rican Independence Party, Lebrón was "the mother of the independence movement."

Lebrón claimed that she had renounced violence due to her religious convictions, and she maintained the new pledge of nonviolence for the rest of her life. However, Lebrón stated that although she herself would not take up arms, "I acknowledge that the people have a right to use any means available to free themselves."

Although votes for independence in Puerto Rico typically garner up to 5 percent of the vote and statehood accounts for up to 50 percent of the vote, Puerto Rico remains a colony of the United States empire. And Lolita Lebrón never repented for her actions. When released, she said "We didn't do anything that we should regret. Everyone has the right to defend their right to freedom that God gave them."

#Puerto Rico#Lolita Lebron#Puerto Rican Independence Party#us colonialism#colonies of america#Free Puerto Rico#The 1954 Attack On The Capitol And The Woman Who Led It

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#pedro albizu campos#despierta boricua#todo lo bueno de puerto rico#lo bueno de puerto rico#yo soy boricua pa'que tu lo sepas#puertorriqueños#grandes puertorriqueños#boricuasporelmundo#boricuas be like#boricuas en new york#boricuas#la cultura puertorriqueña

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Valor doesn't have to equal physical force. The most feeble woman can bring down an empire, if she has valor. Grip hard your rosary, and step forward. Our women will push our men to be the valiant figures they were born to be. Women in Puerto Rico have not given birth to cowardly men.

-Pedro Albizu Campos

1 note

·

View note

Text

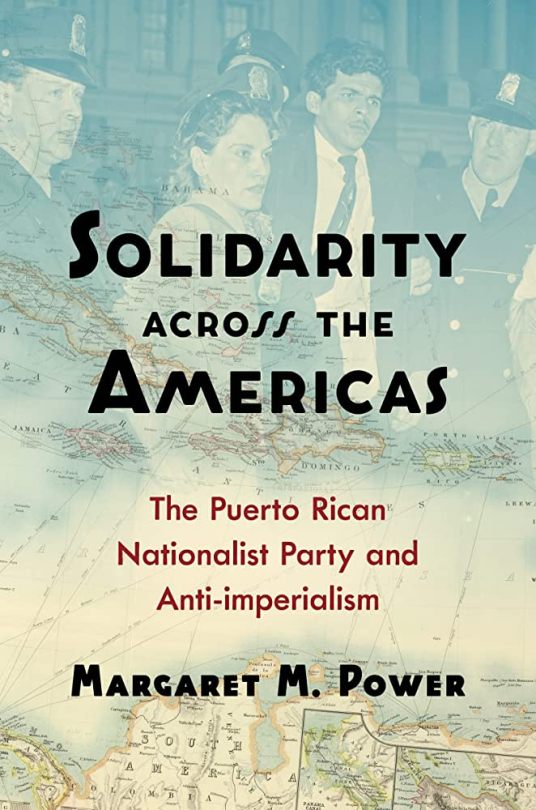

"This fascinating story often decenters the party's history from Pedro Albizu Campos and illuminates lesser-known and unknown characters while also decentering the history of the party from a strictly Puerto Rican setting. A fine read!"

#uwlibraries#history books#puerto rican history#caribbean history#political history#american history

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

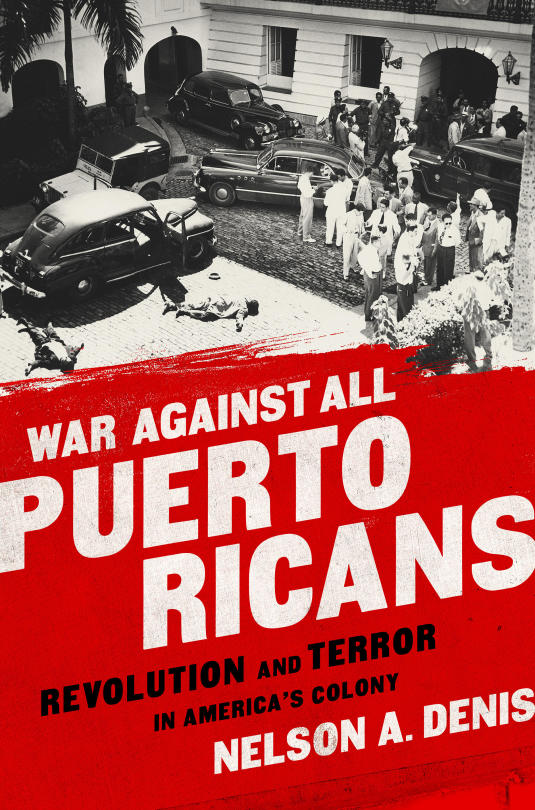

"War Against All Puerto Ricans"

Puerto Rico is back in the news.

Sorta.

That Other America breaches the US media consciousness every couple of years. The Bad President put it in the news by his horrific, racist failure to respond to Hurricane Maria:

https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/it-totally-belittled-the-moment-many-look-back-in-anger-at-trumps-tossing-of-paper-towels-in-puerto-rico/2018/09/13/8a3647d2-b77e-11e8-a2c5-3187f427e253_story.html

And the Good President put Puerto Rico in the news by sidelining its elected government because they had the temerity to stiff his buddies on Wall Street, just like GW Bush did to Flint when they crossed the same line:

https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/economy/obama-signs-law-to-rescue-puerto-ricos-economy/2016/06/30/882fbc7e-3ed7-11e6-84e8-1580c7db5275_story.html

The finance bros that Obama put in charge of the island turned it into an offshore Flint, starving its utilities in order to extract more debt payments to the finance sector. The ensuing neglect meant that when Maria hit, the power infrastructure collapsed, leaving the US citizens of Puerto Rico without electricity for three months.

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/29/us/puerto-rico-power-outage.html

Donald Trump couldn’t have murdered thousands of Puerto Ricans and immiserated millions more without Barack Obama’s help. But that’s unfair to both Trump and Obama: they were merely carrying on a centuries-long tradition stretching back to Teddy Roosevelt, a bedrock American heritage of racism, neglect, enslavement, torture, and extraction (so. much. extraction.).

Puerto Rico is back in the news. The island territory — where US citizens do not get to vote for the president nor send a voting representative to Congress — is planning a binding referendum on whether to become a US state, or whether to secede from the USA altogether.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/jul/20/puerto-rico-statehood-independent-free-association-debate

As it happens, I just became a US citizen. As a Californian, I am (nominally) protected by the US Constitution, and in a couple months I will get to vote for my Congressional rep — unlike millions of Puerto Ricans, who have been citizens for generations, but who are not entitled to equal protection under the law — as the Supreme Court just affirmed:

https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/21pdf/20-303_6khn.pdf

Days after I took my citizenship oath, I joined my family for a two-week holiday on Puerto Rico. I arrived with jumbled impressions of the island’s history, gleaned from the odd article, radio documentary and news article. By the time we left, I had a much more coherent understand of the centuries of systematic, ghastly fuckery that these United States of America had visited upon its “commonwealth” and what the stakes are for the referendum.

We started in Old San Juan, where we got oriented via Andy Rivera’s architectural tour, which introduced us to the 500 year history of the city and its colonial masters:

https://www.airbnb.com/experiences/174126

On the tour, I noticed the Librería Laberinto, a bookstore, and made a point of visiting it later that day:

https://librerialaberintopr.com/

That’s where I found Nelson A Denis’s incredible history of the island, War Against All Puerto Ricans, a brilliant, funny, enraging and masterful history of the failed Puerto Rican revolution of 1950, and its leader, the remarkable Pedro Albizu Campos:

https://waragainstallpuertoricans.com/the-book/

Denis is a Cuban/Puerto-Rican-American raised in New York City, whose Cuban-born father was kidnapped and deported to Cuba during the Cuban Missile Crisis, when the FBI indiscriminately shattered families on orders from Bobby Kennedy:

https://nelsondenis.wordpress.com/home/

Denis went on to go to Harvard, where, in 1977, he published a landmark work of historical scholarship in the Harvard Political Review, “The Curious Constitution of Puerto Rico.” From Harvard, Denis continued on to Yale, where he took a law degree — and continued his voracious study of the Puerto Rican revolution and its aftermath.

He conducted years of research — hundreds of FOIA requests, thousands of hours of interviews with the architects, partisans and eyewitnesses — he published his masterpiece, which weaves together the disparate narratives of all the actors in this tragicomedy to present a truth that is far, far stranger than fiction.

For generations, Puerto Rico was a classic imperial periphery, the place where eminent families sent their failsons for a second chance. The most rapacious corporations in American — along with the US military — established operations in PR and staffed them with a clown cavalcade of idiots and sadists, who, by dint of birth, were put in a position of power over the people of Puerto Rico.

Each of these men came to Puerto Rico to seek their fortune, and, by and large, they found it — extracted it, rather, from the sweat and blood of Puerto Ricans. They committed gaffes, scams and atrocities and then went back to the mainland, where they were celebrated.

Take Dr Cornelius Rhoads, an eminent physician whose tenure as an island hospital administrator was cut short when his maid discovered a letter he’d written to a mainland colleague in which he railed against Puerto Ricans in a vicious, racist tirade, then gloated about having murdered several of his Puerto Rican patients as part of a genocidal campaign to rid the island of its islanders:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cornelius_P._Rhoads

Despite having admitted to a string of racially motivated murders, Rhoads was celebrated on his return. He became an army doctor, developed chemical weapons, and went on to appear on the cover of Time magazine as a great hero.

In some ways, it’s not surprising that Rhoads would be lionized for murdering Puerto Ricans. After all, a legion of white doctors participated in the forced sterilization of Puerto Rican women from the 1930s to the 1970s, ultimately sterlizing a third of the island’s women:

https://www.panoramas.pitt.edu/health-and-society/dark-history-forced-sterilization-latina-women

I’d heard of Rhoads, but not of the many other failsons whose lives Denis chronicles — the governor who arrived on the island with a plan to remake it as an animal training center where nightingales would learn to sing “The Stars and Stripes Forever” for sale to patriotic Texans at $50 a pop. I also didn’t know about the army — literal and figurative — of FBI agents who employed a vast network of informants to produce detailed, paranoid dossiers on the people of the island.

More importantly, I didn’t know about the Puerto Ricans who are the true heroes of this tale, like Albizu, orphaned as a small boy following his mother’s suicide, who raised himself, became a prodigy, attended Harvard, and excelled at everything he did. Albizu — brilliant, driven, committed — refused offers to clerk for the Supreme Court or work for large American corporations, and instead returned to Puerto Rico to work as a poor peoples’ lawyer. He went on to lead the revolutionary independence movement, and was tortured to death by America in return.

Albizu is just one of the many larger-than-life, tragic heroes of Denis’s tale: there’s Juan Emilio Viguié, a self-taught virtuoso filmmaker who left the island to work as the embedded documentarian for Pancho Villa’s army, returned home, and became the Zapruder of the Ponce massacre, a grisly atrocity whose architects — more failsons from the mainland — were never held to account for.

There’s also Vidal Santiago Díaz — a barber turned gunrunner, who supplied the independence movement with arms and a secret meeting place, all under the nose of the FBI, who eventually helped the island police kidnap him and subject him to barbaric torture. On his release, Díaz returned to his barbershop, recovered his cached weapons, and held off thirty armed men singlehandedly from within the shop, for hours, as the nation listened in to live, play-by-play radio reporting. Eventually, they gassed Díaz, entered his shop, and shot him in the head. They dragged him into the street for the news-crews to photograph, but he surprised them by reviving and denouncing the police. He was taken to a cell to die, but not before he recounted his side of the storied, fabled battle.

These are the protagonists of Denis’s narrative, with the failsons serving as foils, villains, and color — like Waller Booth, a spy with the OSS (forerunner to the CIA) who came to the island to spy on nationalists. He set up an after-hours club themed after his favorite movie, Casablanca, which he screened on repeat in a private room in the club. Nationalists would sit and watch the movie every night, in the manner of Rocky Horror, and shout witty lines at the screen: “We’ll always have the FBI!” and “Round up the usual Nationalists!”

Denis builds up his story one character or event at a time, retelling the tale from different angles, weaving together the perspectives of his people over and over, using them to illuminate different aspects of the degradation and pillaging of Puerto Rico and the indomitable spirit of its people. It is in this fashion, for example, that Denis dissects — and demolishes — the 1917 law that Congress passed in the name of Puerto Rican self-determination, but which really only served to make Puerto Ricans subject to the draft.

So it goes, in Denis’s history: an American conglomerate or politician comes up with a new and depraved way to profit from the islanders, and they resist — against all odds, in the face of violent repression. The revolution itself — which included an attempt on Truman’s life — plays out with the drama of a war movie.

Apart from their Puerto Ricanness, the protagonists of this story would make great American folkloric heroes, Horatio Algers who came from humble beginnings, succeeded through thrift, tireless striving and indomitable will, devoted themselves to justice, and stood up to bullies — and paid with their lives for a righteous cause.

But because the bullies they stood up to were operating as agents of America, they are forgotten. Not even reviled — erased. On the American mainland, the Puerto Rican revolution isn’t even a footnote. Indeed, Puerto Rico itself is often forgotten by America, despite the many sons and daughters of the island who have fought for its military. Remember Maria, when Trump and his supporters spoke of Puerto Ricans as foreigners whose “country” was insufficiently grateful for “American charity?”

But this history is not forgotten in Puerto Rico. How could it be? After all, the disappearances and torture — which included mad science experiments in which political prisoners were irradiated until they perished — did not take place in some distant past. As Denis’s end-notes demonstrate, many of the people who witnessed these extraordinary events are still alive, and Denis’s work is based on corroborated eyewitness testimony, backed by FOIAed documents.

Denis’s book was indispensable as we traveled around this beautiful, marvelous island, because it is also a small island, and every place we visited had a cameo in the book: the movie theater we took the kids to see Thor at was in a town that once housed a nightmare gulag where Nationalists were electrocuted, starved and shot.

By superimposing the crimes of empire over the landscape, we were able to get some context for the flags, the graffiti, and the news about the looming referendum.

One day in a taxi, the driver talked to us about the referendum: I mentioned that I had just become a US citizen and for my sake, I would like Puerto Rico to become a state and gain two senators, but for their sake, it seemed that independence would be a better deal.

She agreed vigorously, and spoke of the crypto-bros and pharma companies that descended on the island with the idea of turning it into a kind of hyper-Delaware, an onshore-offshore regulation and tax haven, just as the sugar-barons and other failsons of the mainland had done for more than a century.

Visiting Puerto Rico was the perfect commemoration of my US citizenship — a chance to eat some of America’s best food, listen to some of its greatest music, see its most beautiful national forest, meet some of its friendliest people, see some of its most beautiful art — and learn of some of its most vicious crimes. Puerto Rico is the only place where the US military bombed US citizens, but, of course, the US military has bombed many, many places.

The contradictory currents that pull at America are all in sharp relief on the island. It has served as a lab for so many of America’s worst ideas, and also as a proving ground for the resistance to those ideas.

So much has happened since 2015 when this book was published — and so much of what has happened is an echo of what went before. Denis’s ability to describe the bravery and spirit of those who fight for independence, self-determination and dignity rivals greats like Howard Zinn. Combine that skill with Denis’s personal connection to the material — and the access it gave him to the buried histories of America’s sins — and you get a high-speed masterclass on the choice facing Puerto Ricans today.

[Image ID: The cover of the 2015 Bold Type Books edition of Nelson A Denis's 'War Against All Puerto Ricans.']

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Metas, Trabajo, Logros

Camilla Decamps Villafañe, 26, piloto de American Airlines. Boricua.

"Imagínate estar corriendo un maratón por más de cinco años y por fin llegar a la meta final. Ese fue el sentimiento."

Primera Hora

Orgullo de Puerto Rico

¡Coño! Aprende, boricua. Cero muletas. Cero corrupción.

"No somos pequeños. Es que estamos ñangotados."

— Paráfrasis de don Pedro Albizu Campos

» Mapa del sitio

#Camilla Decamps Villafañe#boricua#orgullo de puerto rico#bravo!#el nuevo puerto rico lo hacemos nosotros

2 notes

·

View notes