#nosism

Text

Nosism

Nosism [nah-si-zəm]Part of speech: nounOrigin: Latin, 19th century1. The use of a first-person plural pronoun (such as “we”) instead of a first-person singular pronoun (such as “I”) to refer to oneself.Examples of nosism in a sentence“We could tell our AirBnB host was a character from his use of nosism and the way he referred to the condo as “The Manor.””“These days, using what is called “the…

youtube

View On WordPress

#daily#definition#dictionary#educational#Knowledge#learning#lesson#Nosism#schoolhouse#vocabulary#word#Youtube

0 notes

Text

ASMR: masturbation quickie (SOUND ONLY)

Krystal Swift's HUGE Natural Tits and Pussy Fucked

Wife fucks BBC friend while husband films

Huge Ass SSBBW Erin Green Gets Worshiped and Stuffed by a Fetishist Grandpa

A beautiful pink pussy by Krystal Orchid

I will lift up my skirt while you jerk your cock JOI

MILF Big Tits Blowjob and Handjob my Huge Cock

MomsWithBoys - Fucking Sexy MILF Seducing The Water Delivery Guy

casino saint amand

Black trans babe barebacked by big cock

#peripetasma#Shoshonean-nahuatlan#interrogatory#binding#spray#iran#wire-pull#rubylike#immaterialism#nesslerise#ribands#Eugenia#duodecimomos#Raven#holochordate#anniv#nosism#Egidius#time-economizing#awe-inspiringly

0 notes

Text

Thinking of wild AU concepts tonight and came back to the Amalgam AU idea I had for Resident Evil. It lifts a lot of System Shock 2's dynamic with SHODAN and the Many, but essentially Leon nearly dies in Gaiden after his solo encounter with the B.O.W. parasite. Turns out that parasite had just beaten up the newer, second parasite, so the new parasite clings and melds itself into Leon in order to stay alive. That's why the cut on his throat bleeds green in the ending. Leon just thinks he passed out and is unaware of most of this.

Flash-forward to RE4 and Leon's asking Ashley if she's hearing the weird multiple voices speaking in her head too. Ashley's confused because she isn't, and there's differing symptoms of infection between her and Leon. They chalk it up to plaga behavior, but it really becomes noticeable when Leon successfully gets Ashley treated and passes out.

Ashley wakes up to Leon on the ground, looking more emaciated than normal... like he's lost a significant amount of flesh. Is that even possible?

Then a shadow flits across the wall.

She screams when there's another Leon - a younger, bloodied, Leon, asking her to help "our host".

The Amalgam tells her that they had reached a symbiotic relationship with their host, until this intruder began to ruin their union. "If you repay our favor, then our unity shall be restored. Our intruder shall live as one with us."

Ashley is trying SO hard to not panic because there's one version of Leon speaking like a hive mind with nosism, and the other one is passed out looking super plaga infected at this point. She asks what the Amalgam is, and they politely recite their backstory.

"And what will this... unity mean for Leon?" she asks.

The younger copy's dull eyes seem to look puzzled. "We have always been one. We will return to our harmony, together."

Okay, so this... thing was in Leon the whole time? How come it didn't present itself before? And what's cooperating with it going to do to Leon.

The copy smiles.

"But you fear us. We hear your thoughts - and they rage for the one you believe dead. But he is not. He sleeps in us."*

She eventually agrees, and the copy... merges back into the other body? And when she props Leon up and runs the machine, it malfunctions mid-way. But the inky veins vanish, and Leon opens his eyes.

Cloudy, dull eyes.

Ashley grabs a nearby scalpel before Leon dissuades her. It's the same professional, slightly awkward tone he'd had for the entirety of their time here, which lets her relax, a little. In fact, Leon's the one who's most startled when the Amalgam mentally projects their gratitude to Ashley, now with another voice in their choir.

Anyway, the rest of the AU would be the events of RE4 where Ashley and Leon have to deal with Leon's secret dual parasite hivemind that's now part cruise-ship parasite and plaga. With body double fun times too, because that's a thing Leon can do now.

#random musings#resident evil#resident evil 4#re4#will i ever stop making obscure and silly headcanons?#leon kennedy#ashley graham#this makes more sense in my head I swear lol#but it's 99% indulgent system shock body horror#the asterisked quote is a slightly edited quote from the Many in system shock 2#everything else is from my silly brain#bits and baubles#tw body horror#amalgam hivemind would go OFF against saddler btw#“a lost individual wishing to ruin the harmony he has amassed” they complain#meanwhile leon is like “please I just wanna say dumb eye-based one liners”#anyway if I wrote a fic for this it'd revolve around ashley figuring out how she's gonna live her life after this#she got kidnapped to be a pawn#and her convos with amalgam/leon make it even more clear to her she wants to do her own thing#plus leon now has to deal with this wacky biohazard infection i've cooked up

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

For a long time, I called my let’s plays “let’e plays”, “let’e play” meaning “let me play”. But I stopped, because I started thinking of “let us play” as use of the royal “we”.

Nosism

0 notes

Text

sri lankan forenames + deceases

Abscition Admints Ageepth Ajana Alindic Amana Amanusana Aminda Amumons Amuthydia Andranu Angam Anirls' Anthanth Anthes Apala Apatis Appekshma Apraw Araju Arama Aranjani Aranthiya Ariosan Armanam Armani Armatis Armenpox Armethys' Armitis Aropox Arshan Arubuni Arumalina Aruwa Asara Aseptia Astiomi Asunte Athypox Atilvaka Atkira Babersh Babie Babise Bablera Bablita Babscrano Basid Bayes Bermity Betonika Bookanth Botil Botomoni Broia Brula Brunam Bubishili Bubuna Budessara Cababa Cabelvan Canjitra Chala Chalgia Chana Chanania Chani Chanka Chanth Chantham Chanthan Chants Chanus Chara Chari Charichan Chariya Charts Charu Charuces Charumal Charus Chavo Chicke Chila Chindi Chindidi Chinnan Chino Chlaka Choba Chorika Choriman Coccitis Colessi Condravik Conica Conimpati Conomi Consis Cosha Cosis Cosism Cosiss Cospia Cowpot Damusi Damydi Dasis Deeptiss Dehano Dehatish Demity Denel Dermana Derophy Derwil Dhalaka Dhandris Dhanie Dishala Dylkanika Ediyanthi Emaran Encenirts Enirasama Epton Ermeni Fibetis Fibets Ficepsi Fickea Galis Gayes Gemindris Gemini Gineop Giranka Hamiti Handu Hasania Heets Hehani Hepalabie Herodeeta Herop Heted Hetosis Hitis Hitithri Hydia Hypoth Hypox Hyrimal Hyrosis Hyrosisha Ilicte Iloit Indamia Inferosis Influe Inginot Inika Inilan Iniriya Inobass Insirtis Iriber Irivai Jacold Jatulass Jayadaka Jebangan Jebies Jebooka Jeets Jegathi Jehydion Jeyara Junloada Kamadma Kamal Kandraxia Kanjithan Kibaba Kirithric Kithulot Kosiree Kosis Kulandis Kulpolion Kulpriya Kumahi Kumasis Kumen Kumenuri Kumon Kusha Kusiran Kuwan Kuwari Lakumphu Lalago Lallokuka Lancha Lankameni Larasee Larayea Larsishi Lasiria Lasis Leitinima Leryno Lesirinia Lindulani Litha Loitis Loksh Lomage Losilia Losina Losis Loys' Lyasila Lymonsis Malak Malinika Malism Maneflu Manth Mapri Mariya Matis Matitiss Mavai Mayasa Menis Menthi Ments Menuwa Menza Miastigo Minala Monthyris Muguengia Mumen Muttis Myapie Myarus Mycold Myelihi Myella Myoccith Myxeditia Nakuwatha Nalictis Namus Nessal Neumor Niaswis Niremugue Nosism Obabi Osilika Osisedaka Othes Otosi Padayadma Pasis Pathal Patharat Pedima Penza Perath Percula Perinoman Periya Pertha Pirosis Piyama Plabis Plaka Preks Priah Pricali Prika Primatha Prittitis Priyan Proidi Prosi Prosis Prosism Psity Psomittat Pubudee Radma Ramars Randass Ranjity Rathi Rathri Ratis Repalis Rhemini Rhetone Rodeshi Rohindra Rohithan Rosis Saenika Saenil Saenza Salegitha Samana Sangamma Sanis Sanka Sanoba Santedis Sarnala Sarula Scala Scelli Schani Schanus Schathi Sclepia Scloidenu Sculareni Seephi Seewarvy Sellinda Senguni Senpox Senuce Senza Sepasis Sepiyasm Septhani Septhity Shalani Shanada Shanala Shandia Shanjeha Shant Sharju Shathige Shmavo Sholi Silis Sirani Sirinika Siriti Siriya Siriyasis Sisharism Sistions Sokshan Srimpeni Srity Sriyan Sriyant Sriyast Stedicity Sthala Sujan Sujayan Sumago Sumah Sumala Sumpia Sungia Suniricem Sunyloy Susan Sushomy Susiriya Susivaj Tetris Thilitis Threka Thula Tiaswika Tickbothi Tilini Tionis Tiosis Tishma Tithris Tonilika Trasta Trearmai Treka Tremili Triya Troity Tuharsis Tulprem Tumania Turan Tushan Tuwarsh Uddasama Udilinia Uduli Ukani Ukkuka Ukkus Ukkuwatis Unarax Upeka Upetus Upubes Upubi Upula Urasalka Uruwa Ushomyani Usilan Uvatha Uveithri Vajitis Vajuni Vanalaka Varshali Vidanari Videnies Viniasis Vithi Vitreni Wasani Wasis Wilith Winflune Winthrima Wrinna Yania Yasiria Yellage Yuveish

#name stash#444names#444 names#dnd names#character names#random character names#markov namegen#markov name generation#markov#markov gen

0 notes

Text

So when are we going to prove that Barthelemy was Godfrey’s accomplice in Queen Eleanor’s murder? Because that’s clearly what happened. And I cannot believe when Godfrey said “we” that the gang just dismissed it as him using nosism/pluralis majestatis without looking into it any further. No. You investigate that shit. I’m especially disappointed in Liam and Hana, the two smartest people in the bunch. They should’ve investigated further the minute that “we” left Godfrey’s mouth.

#choices stories you play#playchoices#choices stories we play#pixelberry#pixelberry studios#trr#choices trr#the royal romance#choices the royal romance#choices trh#trh#the royal heir#choices the royal heir#barthelemy beaumont#liam rys#Hana lee#maxwell beaumont#drake walker#Riley brooks

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

whats the grammatical scoop on the singular “we”, and i dont mean like systems, i mean like video game videos/streams in which the player refers to their actions as being performed by some collective “us”. for example: “first, we need to go collect kameks star coupons, so we can unlock the roulette minigame” or something like that. i think it shows up in some acedemic writing. no idea what to google https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nosism the author’s we

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Towards Relational Design by Andrew Blauvelt

Is there an overarching philosophy that can connect projects from such diverse fields as architecture, graphic and product design? Or are we beyond such pronouncements? Should we even expect such grand narratives anymore?

I’ve spent more time in the field of graphic design, and within that one discipline it is extremely difficult to pinpoint coherent sets of ideas or beliefs guiding recent work — certainly nothing as definitive as in previous decades, whether the mannerisms of so-called grunge typography, the gloss of a term such as postmodernism, or even the reactionary label of neo-modernism. After looking at a variety of projects across the design fields and lecturing on the topic, new patterns do emerge. Some of the most interesting work today is not reducible to the same polemic of form and counter-form, action and reaction, which has become the predictable basis for most on-going debates for decades. Instead, we are in the midst of a much larger paradigm shift across all design disciplines, one that is uneven in its development, but is potentially more transformative than previous isms, or micro-historic trends, would indicate. More specifically, I believe we are in the third major phase of modern design history: an era of relationally-based, contextually-specific design.

The first phase of modern design, born in the early twentieth century, was a search for a language of form that was plastic or mutable, a visual syntax that could be learned and thus disseminated rationally and potentially universally. This phase witnessed a succession of “isms” — Suprematism, Futurism, Constructivism, de Stijl, ad infinitum — that inevitably fused the notion of an avant-garde as synonymous with formal innovation itself. Indeed, it is this inheritance of modernism that allows us to speak of a “visual language” of design at all. The values of simplification, reduction, and essentialism determine the direction of most abstract, formal design languages. One can trace this evolution from the early Russian Constructivists’ belief in a universal language of form that could transcend class and social differences (literate versus oral culture) to the abstracted logotypes of the 1960s and 1970s that could help bridge the cultural divides of transnational corporations: from El Lissitzsky’s “Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge” poster to the perfect union of syntactic and semantic form in Target’s bullseye logo.

The second wave of design, born in the 1960s, focused on design’s meaning-making potential, its symbolic value, its semantic dimension and narrative potential, and thus was preoccupied with its essential content. This wave continued in different ways for several decades, reaching its apogee in graphic design in the 1980s and early 1990s, with the ultimate claim of “authorship” by designers (i.e., controlling content and thus form), and in theories about product semantics, which sought to embody in their forms the functional and cultural symbolism of objects and their forms. Architects such as Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, and Steven Izenour’s famous content analysis of the vernacular commercial strip of Las Vegas or the meaning-making exercises of the design work coming out of Cranbrook Academy of Art in the 1980s are emblematic. Importantly, in this phase of design, the making of meaning was still located with the designer, although much discussion took place about a reader’s multiple interpretations. In the end though, meaning was still a “gift” presented by designers-as-authors to their audiences. If in the first phase form begets form, then in this second phase, injecting content into the equation produced new forms. Or, as philosopher Henri Lefebvre once said, “Surely there comes a moment when formalism is exhausted, when only a new injection of content into form can destroy it and so open up the way to innovation.” To paraphrase Lefebvre, only a new injection of context into the form-content equation can destroy it, thus opening new paths to innovation.

The third wave of design began in the mid-1990s and explores design’s performative dimension: its effects on users, its pragmatic and programmatic constraints, its rhetorical impact, and its ability to facilitate social interactions. Like many things that emerged in the 1990s, it was tightly linked to digital technologies, even inspired by its metaphors (e.g., social networking, open source collaboration, interactivity), but not limited only to the world of zeroes and ones. This phase both follows and departs from twentieth-century experiments in form and content, which have traditionally defined the spheres of avant-garde practice. However, the new practices of relational design include performative, pragmatic, programmatic, process-oriented, open-ended, experiential and participatory elements. This new phase is preoccupied with design’s effects — extending beyond the design object and even its connotations and cultural symbolism.

We might chart the movement of these three phases of design, in linguistic terms, as moving from form to content to context; or, in the parlance of semiotics, from syntax to semantics to pragmatics. This outward expansion of ideas moves, like ripples on a pond, from the formal logic of the designed object, to the symbolic or cultural logic of the meanings such forms evoke, and finally to the programmatic logic of both design’s production and the sites of its consumption — the messy reality of its ultimate context.

Design, because of its functional intentions, has always had a relational dimension. In other words, all forms of design produce effects, some small, some large. But what is different about this phase of design is the primary role that has been given to areas that once seemed beyond the purview of design’s form and content equation. For example, the imagined and often idealized audience becomes an actual user(s) — the so-called “market of one” promised by mass customization and print-on-demand; or perhaps the “end-user” becomes the designer themselves, through do-it-yourself projects, the creative hacking of existing designs, or by “crowdsourcing,” producing with like-minded peers to solve problems previously too complex or expensive to solve in conventional ways. This is the promise that Time magazine made when it named you (a nosism, like the royal we) person of the year in 2006, even as it evoked the emerging dominance of sites such as MySpace, Facebook, Wikipedia, Ebay, Amazon, Flickr and YouTube, or anticipated the business model of Threadless. The participation of the user in the creation of the design can be seen in the numerous do-it-yourself projects in magazines such as Craft, Make and Readymade, but they can also be seen in the generic formats for advertisements and greeting cards by Daniel Eatock.

Even in most instrumental forms of design, the audience has changed from the clichéd focus group sequestered in a room answering questions for people hiding behind two-way mirrors to the subjects of dogged ethnographic research, observed in their natural surroundings — moving away from the idealized concept of use toward the complex reality of behavior. Today, the audience is thought of as a social being, one who is exhaustively data-mined and geo-demographically profiled — taking us from the idea of an average or composite consumer to an individual purchaser among others living a similar social lifestyle community. But unlike previous experiments in 1970s-style community-based design or behavioral modification, today’s relationship to the user is more nuanced and complicated. The range of practices varies greatly, from the product development methods employed by practices such as IDEO, creators of the famed Nightline shopping cart, to the “social probes[,]” of Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby who create designed objects, not to fulfill prescribed functions but instead use them to gauge behavioral reactions to the perceived effects of electromagnetic energy or the ethical dilemmas of gene testing and restorative therapies.

Once shunned or reluctantly tolerated, constraints — financial, aesthetic, social, or otherwise — are frequently embraced not as limits to personal expression or professional freedom, but rather as opportunities to guide the development of designs; arbitrary variables in the equation that can alter the course of a design’s development. Seen as a good thing, such restrictions inject outside influence into an otherwise idealized process and, for some, a certain element of unpredictability and even randomness alters the course of events. Embracing constraints — whether strictly applying existing zoning codes as a way to literally shape a building or an ethos of material efficiency embodied in print-on-demand — as creative forces, not obstacles on the path of design, further opens the design process demanding ever-more nimble, agile and responsive systems. This is not to suggest that design is not always already constrained by numerous factors beyond its control, but rather that such encumbrances can be viewed productively as affordances. In architecture, the discourse has shifted from the purity and organizational control of space to the inhabitation of real places — the messy realities of actual lives, living patterns over time, programmatic contradictions, zoning restrictions, and social, not simply physical, sites. For instance, architect Teddy Cruz in his Manufactured Sites project, offers a simple, prefabricated steel framework for use in the shantytowns on the outskirts of Tijuana — a structure that participates in the vernacular building practices that imports and recycles the detritus of Southern California’s dismantled suburbia. This provisional gesture integrates itself into the existing conditions of an architecture born out of crisis. The objective is not the utopian tabla rasa of architectural modernism — a replacement of the favela — but rather the interjection of a micro-utopian element into the mix.

Not surprisingly, the very nature of design and the traditional roles of the designer and consumer have shifted dramatically. In the 1980s, the desktop publishing revolution threatened to make every computer user a designer, but in reality it served to expand the role of the designer as author and publisher. The real “threat” arrived with the advent of Web 2.0 and the social networking and mass collaborative sites that it has engendered. Just as the role of the user has expanded and even encompasses the role of the traditional designer at times (in the guise of futurist Alvin Toffler’s prophetic “prosumer”), the nature of design itself has broadened from giving form to discrete objects to the creation of systems and more open-ended frameworks for engagement: designs for making designs. Yesterday’s designer was closely linked with the command-control vision of the engineer, but today’s designer is closer to the if-then approach of the programmer. It is this programmatic or social logic that holds sway in relational design, eclipsing the cultural and symbolic logic of content-based design and the aesthetic and formal logic of modernism’s initial phase. Relational design is obsessed with processes and systems to generate designs, which do not follow the same linear, cybernetic logic of yesteryear. For instance, the typographic logic of the Univers family of fonts, established a predictive system and closed set of varying typeface weights. By contrast, a Web-based application for Twin, a typeface by Letterror, can alter its appearance incrementally based on such seemingly arbitrary factors as air temperature or wind speed. In a recent design for a new graphic design museum in the Netherlands, Lust created a digital, automated “posterwall,” feed by information streams from various Internet sources and governed by algorithms designed to produce 600 posters a day.

Perhaps the best illustration of this movement toward relational design can be gleaned through the prosaic vacuum cleaner. In the realm of the syntactical and formal, we have the Dirt Devil Kone, designed by Karim Rashid, a sleek conical object that looks so good it “can be left on display.” While the vacuum designs of James Dyson are rooted in a classic functionalist approach, the designs themselves embody the meaning of function, using color-coded segmentation of parts and even the expressive symbolism of a pivoting ball to connote a high-tech approach to domestic cleaning. On the other hand, the Roomba, a robotic vacuum cleaner, uses various sensors and programming to establish its physical relationship to the room it cleans, forsaking any continuous contact with its human users, with only the occasional encounter with a house pet. In a display of advanced product development, however, the company that makes the Roomba now offers a basic kit that can be modified by robot enthusiasts in numerous, unscripted ways, placing design and innovation in the hands of its customers.

If the first phase of design offered us infinite forms and the second phase variable interpretations — the injection of content to create new forms — then the third phase presents a multitude of contingent or conditional solutions: open-ended rather than closed systems; real world constraints and contexts over idealized utopias; relational connections instead of reflexive imbrication; in lieu of the forelorn designer, the possibility of many designers; the loss of designs that are highly controlled and prescribed and the ascendency of enabling or generative systems; the end of discrete objects, hermetic meanings, and the beginning of connected ecologies.

After 100 years of experiments in form and content, design now explores the realm of context in all its manifestations — social, cultural, political, geographic, technological, philosophical, informatic, etc. Because the results of such work do not coalesce into a unified formal argument and because they defy conventional working models and processes, it may not be apparent that the diversity of forms and practices unleashed may determine the trajectory of design for the next century.

Andrew Blauvelt, Towards Relational Design (2008) Design Observer, 07.09.20

0 notes

Text

Alaskan Malamute AMvengers Marvel Endgame shirt

Alaskan Malamute AMvengers Marvel Endgame shirt

Maybe it stemmed from that? What’s worse is falling into the habit of nosisms or the use of “the Alaskan Malamute AMvengers Marvel Endgame shirt.” I’ve started writing scientific papers, where it tends to be used the most, but now I’ve slipped into the habit of using it in less formal writing and it looks weird as hell. Most of what people say is implicitly really saying something about…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

we

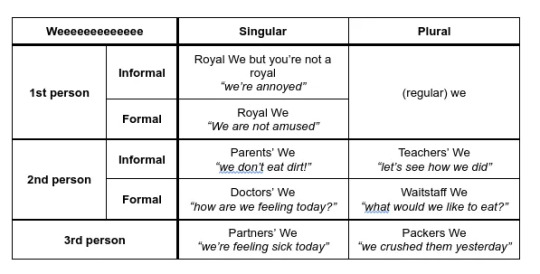

A nosism is the use of ‘we’ to refer to oneself. The speakers/writers, or the speaker/writer and at least one other person. The speaker/writer alone. (The use of we in the singular is the editorial we, used by writers and others, including royalty—the royal we—as a less personal substitute for I.

source

0 notes

Text

The corporate ‘we’

Q: This sentence is on a literary agency website: “We offer our clients unusually meaningful editorial guidance and inspiration, and serve as their advocate throughout the publishing process.” Shouldn’t “we” take the plural “advocates”?

A: The literary agency is using what’s often called “the corporate we.” The firm itself is the “advocate” (singular), but refers to itself in the plural (“we”).

This is a very common practice in business language; in fact, it’s the rule rather than the exception in corporate discourse.

A company, an organization, or an institution will commonly refer to itself with the first-person plural “we” (along with “us,” “our,” and “ourselves” where appropriate), rather than with the impersonal pronoun “it.”

Here are some examples plucked randomly from the Internet. Note that in each case a singular entity (“company,” “university,” “medical center,” “firm”) refers to itself in the plural:

“We want to be your car company” … “We’re America’s first research university” … “We are a not-for-profit, 912-bed academic medical center” … “We are a major employer in the area” … “As a ‘main street’ accounting firm, we set ourselves apart” … “As a company we pride ourselves on our customer service and satisfaction” … “But we’re not just bigger—we’re one of the best colleges” … “It’s what makes us the business we are today.”

And commercial and institutional websites invariably use language like “who we are” and “what we do,” never “what it is” and “what it does.”

The corporate “we” isn’t a recent invention. You can find commercial examples from the early 20th century. But the usage began to surge in the 1980s, Lester Faigley writes in Fragments of Rationality: Postmodernity and the Subject of Composition (1992).

“Use of the corporate we is one of the tactics stressed in popular books on corporate management during the 1980s,” Faigley writes, mentioning specifically the influential book Corporate Cultures (1982), by Terrence E. Deal and Allan A. Kennedy. That book refers to the use of “we” as “a clever ploy for communicating corporate principles.”

Another book, Ruth Breze’s Corporate Discourse (2013), has this to say:

“There is an almost overwhelming insistence on collective identity: the corporate ‘we,’ which reports achievements in positive terms, and is used variously to include ‘we the employees,’ ‘we the management,’ ‘we the company and its investors’ and ‘we the general public.’ Self-praise is risky when one individual indulges it in front of others. … However, self-praise is socially admissible if the entity being praised is a collective ‘us’ that potentially involves the reader/listener.”

The corporate usage isn’t the only notable “we” on the landscape. Two others have been around for much longer—the “editorial we” and the “royal we.”

The “editorial we” is sometimes adopted by the author of a book or article, particularly an opinion column. It’s defined in the Oxford English Dictionary as “the pronoun we used by a single person to denote himself, as in an editorial.”

The dictionary’s earliest example is from a letter written by Charles Dickens in 1841: “Every rotten-hearted pander who … struts it in the Editorial We once a week.”

The “royal we,” the oldest of the three, is the one used by English kings and queens. The OED defines the “royal we” as “the pronoun ‘we’ used in place of ‘I’ by a monarch or other person in power, esp. in formal declarations, or (frequently humorously) by any individual.”

The earliest definite known use in English is from a proclamation of Henry III in 1298, the dictionary says. But perhaps the most famous example is Queen Victoria’s reported response to a joke told at dinner: “We are not amused.”

(The remark was passed on by Her Majesty’s secretary, and reported in the press during her lifetime, but it has never been definitively confirmed.)

The practice of referring to oneself in the plural actually has a name, “nosism,” as the two of us wrote on our blog in 2011. The word comes from the Latin nos (“we”), so it literally means we-ism.

Help support the Grammarphobia Blog with your donation.

And check out our books about the English language.

from Blog – Grammarphobia https://www.grammarphobia.com/blog/2017/12/the-corporate-we.html

0 notes

Text

Disclaimer/Letter of Intent

Disclaimer

WE ARE IN NO WAY QUALIFIED TO BE A MUSIC CRITIC.

We played clarinet for two years in elementary school. We took choir for 6 semesters in high school. We know the requisite power and open guitar chords to play Smoke on the Water. We have diverse taste in the music to which I listen. These are all the claims we make to music aficionado status. It is highly likely we will say dumb/uninformed/ridiculous things in the course of this blog.

This blog is intended to be useful to no one but us.

This blog is an attempt to kill two birds with one stone.

Bird the first: Write more.

Bird the second: Listen to more music.

To the extent this blog is interesting to others, we welcome feedback and discussion. We make no claims as to the accuracy or efficacy of the text contained within. Consult your physician/attorney/spiritual advisor before beginning any blog consumption program.

Letter of Intent

Our initial plan is to select a recording artist in whom we are interested - indeed, perhaps familiar - but whose catalog we wish to more fully explore. Each week we will listen to an album in their catalog, moving chronologically from earliest to latest, according to AllMusic (albums only, excluding compilations, singles & EPs, et cetera).

We will endeavor to listen to the album each day, ideally in whole but at a minimum in part. We will further endeavor to write something regarding our experience of listening to the album each day. This may be a quick note or a lengthy dissertation. Toward the end of the week we will write some sort of closing statement on the album and preview the next week’s selection.

As it happens - and purely by accident - we are writing this launch statement on a Tuesday, which seems appropriate as Tuesday was historically Record Release Day in the United States (which we are just now learning was changed to align with the rest of the world on the new New Music Friday as of July 10, 2015 - we’re already learning so much!). Thus the blog will roll over from one album to the next on Tuesdays.

We will continue in rampant and unabashed nosism so far as it amuses us, despite being neither afflicted by parasitic worms, nor burdened with rodential pocket-dwellers.

Any or all of these declarations are subject to change at the author’s whim, though efforts will be made to communicate changes in a timely fashion.

0 notes

Text

End of queue

My laptop's charging port broke, so I don't wanna use it until my boyfriend has a chance to fix it. Which should be today (when you see this). The queue will be back up and running on Saturday at the latest!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

we

A nosism is the use of ‘we’ to refer to oneself. The speakers/writers, or the speaker/writer and at least one other person. The speaker/writer alone. (The use of we in the singular is the editorial we, used by writers and others, including royalty—the royal we—as a less personal substitute for I.

source

0 notes

Text

we

A nosism is the use of ‘we’ to refer to oneself. The speakers/writers, or the speaker/writer and at least one other person. The speaker/writer alone. (The use of we in the singular is the editorial we, used by writers and others, including royalty—the royal we—as a less personal substitute for I.

source

0 notes