#mendesian perfume

Text

I make perfume! New recipes but also 3 ancient Egyptian recipes. Look for me on etsy by BeanNoneya or Baba Yaga Alchemy. I make Cleopatra's favorite - the Mendesian, the Metopian, and the lotus based one Susinum.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Secrets of Egypt (DSH Perfumes)

In one of her many incarnations, my friend JC served as a special exhibition curator for a major art museum. She recalls the singular experience of receiving a traveling exhibit of ancient Egyptian artifacts:

The most fragile and precious object was the mummified remains of a child, a young girl who was in no condition to make the journey. While two of us could have lifted her up and into the display case, there were six of us just to be certain no harm came to her. We felt very strongly that she should be pulled from the show. The exhibit coordinators appreciated our input… but said that some of the major funding they received hinged on the fact that at least one mummy be included.

Over the years I had been alone in the Gallery at closing, with the lights out, on numerous occasions. However, when I found myself alone with the ancient objects of the Nile, it was somehow different. I sensed a presence. I wasn't necessarily frightened, but I didn't feel the desire to linger, either. The first time that I encountered this feeling, it really took me by surprise because it was palpable… never had I been so struck by the power of seemingly inanimate objects. There was weight and energy and power… almost a smoky essence in the air. It was as if the collective history of all of the objects formed a powerful force that commanded reverence. In that respect, I wasn't alone.

I've held great works of art in my hands over the years. Rembrandt, Warhol, Dali. I've held Walt Whitman's famous hat and a first edition of Leaves of Grass. So many beautiful and awe-inspiring things-- but nothing compares in my mind to the objects from Egypt. They were the real deal.

Waiting at the root of every journey into fragrant history is ancient Egypt, where perfume pervaded all aspects of life, death, and afterlife. For its 2010-11 exhibit entitled Tutankhamun: The Golden King & the Great Pharaohs, the Denver Art Museum commissioned perfumer Dawn Spencer Hurwitz to interpret four notable formulae of the time period: Susinon, Metopion, Megaleion, and The Mendesian. To these, Hurwitz added reworkings of two fragrances from her extant catalog: Arome d’Egypt and Cardamom & Khyphi.

From my armchair travels as a history reader, I was somewhat familiar with kyphi, arguably the best-documented fragrance in pharaonic Egypt. At once perfume, incense, and medicine, kyphi began as a thick paste of raisins, honey, and pulverized aromatic resins macerated in red wine. Mastic, myrrh, frankincense, pine resin, and bdellium (Commiphora wightii, a relative of myrrh also known as gum guggul) were all used in various ratios to build this mighty base. After several days of aging, a variety of aromatic substances were ritually added in a prescribed order. These included sweet flag (Acorus calamus), papyrus (Cyperus papyrus ssp. hadidii), camel grass (Cymbopogon schoenanthus or African lemongrass), aspalathos (a shrub tentatively identified by experts as either caper bush or broom), saffron, spikenard, cinnamon, juniper berries, mint, cassia, cardamom, pine nuts, balm of Gilead buds, cedar, seseli (a flowering member of the carrot family), and bitumen (a naturally occurring black tar used to bind incense mixtures). One can imagine a finished product that smelled formidable, perhaps even overpowering—as befitted the divine rulers who made use of it.

In confronting the challenge of recreating Ancient Egypt through scent, I imagine that Dawn Spencer Hurwitz might have felt a bit like JC cradling the precious, delicate remains of that tiny child-mummy. A perfumer cast in the role of curator, she brought to the project all of the knowledge, zeal, and faith of a duly-deputized priestess of old. But when the end result needs to be marketable in a museum gift shop… the millenia must weigh awful heavy.

We know about the composition and production of kyphi and its companion fragrances because of historians such as Galen, Rufus, Dioscorides, and Plutarch. Due to their careful recordkeeping, a modern perfumer seeking to recreate these signature scents is not left at a disadvantage. It's entirely possible to compound a "reasonable facsimile" of kyphi and even give it a contemporary, personalized twist. But missing from the written recipe is power -- a spiritual significance that takes centuries to accumulate, remains tangible for centuries more, and is impossible to synthesize.

In the Secrets of Egypt museum set kindly gifted to me by a friend, only Susinon (here called 1000 Lilies) is absent. It's just as well; I admit I may not be ready for the essence with which Cleopatra perfumed the sails of her royal vessel, rendering the winds "lovesick" with scent. Instead, I reach first for Keni (The Mendesian), an interpretation of the cinnamon-myrrh accord for which the Delta city of Mendes earned its fame.

Experienced on one axis, Keni certainly does smell like an ancient unguent: hale evergreen and mint notes steeped in a precious chrism. On a second, intersecting axis, I find a burst of modern candy scents -- basil ribbons and cinnamon red-hots, spicy and bright. This is fitting. Drug stores and candy counters share a common ancestor in the apothecary, where medicine and comestible might be one and the same. Owing to my dual love of weird liniments and old-fashioned sweets, Keni (like Heeley's L'Esprit du Tigre) seems right up my alley. But in less than an hour it vanishes, leaving behind only a trace of faint waxy perfume, like that which clings to a candy wrapper once the treat inside has been devoured.

While we travel together, I truly like where Keni is headed. I just wish the trip lasted longer.

Next up: Megaleion. Taking its name variously from a Syracusan perfumer named Megalus and the Greek word megalos (“great”), Megaleion is described as an infusion of cinnamon, cassia, myrrh, and charred frankincense in balanos, an oil derived from seeds of the Balanites aegyptiaca tree. Its preparation is an interesting exercise in alchemical give-and-take. The oil must be kept at a constant boil for days before it is judged ready to receive the aromatic ingredients, whose properties it greedily devours. It remains at a boil for several days more, its scent seeming to diminish as it is stirred. Only when left alone to cool thoroughly does it relinquish all of the fragrance it has absorbed.

Yet it's not cinnamon and cassia I detect most from DSH's version of this age-old accord. Lemongrass and pine conspire to summon up the ghost of juniper berry, one of kyphi's most oft-cited ingredients. The evergreen cypress trees which produce these tiny, blue drupe-like cones originate from Greece, but their presence in Egyptian tombs implies that they were prized across borders and on both sides of life's threshold. In this floral-resinous fragrance hides their appetizing sourness, their astringent bite, and all the implied powers of purification that a Western mind may connect to them.

But the conundrum is this: they are not there. The nose tells lies, and the mind grasps at a ghost.

Antiu (Metopion) confronts the wearer with no such phantoms-- unless you count the galbanum which the name metopion is said to signify, and which here goes nearly undetected. Then again, Dioscorides opines that the best metopion showcases almond over galbanum-- in which case Antiu wins this round. With its notes of fresh carrot-root and pine needle atop a sweet almond foundation, it's a simply pleasant and pleasantly simple fragrance-- sort of a palate cleanser for the challenging course to follow.

When Greek and Arab invaders chiseled their way into ancient Egyptian tombs, they discovered that all of the scented resins, natron salts, and beeswax used to embalm the occupants had mixed with… well, the occupants themselves, biologically speaking. The resulting petrified goo, erroneously labelled pissasphaltus (pitch asphalt), was used to manufacture a range of ancient pharmaceuticals and cosmetics, including a rather esoteric perfume called mūmiyā’. It's said to have smelled like heaven itself-- presumably once you got over the gag factor.

So it is with Arome d'Egypt. A sweet opening marred by a sudden fetid note of wet wood and mushrooms reminds me of spikenard's close relation to that monster of stomach-turning stonk, valerian. Believing myself the possible victim of a primordial scourge, I thrust my arm under my husband’s nose. He takes one sniff, and together we simultaneously intone the solemn incantation against ancient evils: "Eeewwwww!"

Our rough magic works. Shortly thereafter, Arome d’Egypte transforms into a warm, penetrating cinnamon incense with a drydown graced by the cozy, animalic presence of ambrette. I feel at once favored and spared, brushed by a curse and visited by a blessing. Thank the gods!

I'm tempted to preface my final review by saying something conciliatory like “While Cardamom & Khyphi smells very nice indeed…” I mean, it does. A powerful citrus-spice potpourri cozily couched in nougat, it's a fragrance damn near anyone would love to wear. It incorporates enough classic kyphi ingredients (juniper berry, mastic, myrrh) to justify both its name and its place amongst the other Secrets of Egypt. But here's the catch: leaving it until last makes me think less of it. It smells too much like a typical DSH "Yuletide candle" frag for me to suspend disbelief and imagine that it's an authentic reproduction of a great and ancient sacred perfume. I mean, I like it. But when I expect to be Nile-bound, I don’t want to end up back in the Christmas village. You know?

So how to sum up this trip back in time? I keep returning to JC's phrase about a "force that commands reverence". Which of the Secrets of Egypt possesses it? None, to be honest. For a moment, Arome d'Egypt -- with its fear-and-trembling initial salvo -- comes close. But it's ultimately too sweet-mannered to command or enslave me. These are all fine creations, and I sincerely got a kick out of wearing them. But in a strange (and possibly silly) way, I wanted - no, NEEDED - to feel the uncanny breath of some antediluvian entity on the back of my neck, brushing me with a chill right where I applied the perfume.

Still, who knows? I have yet to encounter Susinon/1000 Lilies. Perhaps when I do, the hand of Nefertem herself will extend one of those thousand blossoms my way.

Scent Elements:

Keni (The Mendesian): Bitter almond, cardamom, cassia, cinnamon, sandalwood, benzoin, fragrant wine accord, Atlas cedar, myrrh, pine

Megaleion: Cardamom, cassia, cinnamon, fragrant wine accord, lemongrass, sandalwood, balm of Gilead accord, spikenard, Turkish rose, balsam copaiba, balsam Peru, costus, myrrh, frankincense, pine, sweet flag

Antiu (Metopion): Bitter almond, cardamom, fragrant wine accord, galbanum, lemongrass, sandalwood, rose otto, balm of Gilead accord, honey/beeswax, balsam copaiba, balsam Peru, mastic, myrrh, pine, sweet flag

Arome d’Egypte: Spikenard, cassis, rose, jasmine, labdanum, sandalwood, Virginia cedar, cinnamon bark, amber, benzoin, balsam Peru, frankincense, myrrh, ambrette

Cardamom & Khyphi: Cardamom CO2, cardamom seed absolute, clove bud, plum accord, sugar date accord, sweet orange, honey, juniper berry, labdanum, mastic, myrrh, frankincense, patchouli

1 note

·

View note

Link

By Tom Hale

“Archaeologists at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa have decoded and recreated millennia-old perfume worn by the ancient Egyptians, perhaps even the famed Queen of the Nile herself, Cleopatra.”

“The recipe for the scents was drawn from a series of ancient Greek texts that speak of two Mendesian and Metopian perfumes. Along with a sprinkling of other fragrant oils and natural ingredients, the base note of the two perfumes is myrrh, a tree resin obtained from a flowering plant grown in parts of Africa and Asia.”

Continue reading

#classics#tagamemnon#tagitus#history#ancient history#egypt#ancient egypt#archaeology#archaeologists#university of hawai'i#manoa#perfume#cleopatra#she MAY have worn the perfume#the title is misleading#research#mendesian perfume#metopian perfume#jay silverstein#university of tyumen#recipe#ancient greek#texts#recreation#Tell-El Timai#chemical analysis#Ptolemaic Kingdom#National Geographic Museum#queens of egypt#exhibit

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

https://mailchi.mp/6910beb50809/bloodlust-and-the-aromas-of-ardour?e=[UNIQID]

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Egyptians made various types of perfumes from fragrant plants, oils and fats, employing various methods, and involving various professions1 . Egypt was famous for its luxury and exotic perfumes throughout the ancient world, where perfumes were traditionally named after their town of origin such as ‘The Mendesian’, or their main ingredient such as lily perfume or susinon. One perfume was simply called ‘The Egyptian’. To the ancient Egyptians incense, another form of perfume, was the ‘eye of Horus’ and the fragrance released from burning it, the divine presence, with vast quantities thereof being required for use in temples, rituals, ceremonies and festivals - SHEILA ANN BYL

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Painting by Alexandre Cabanel

Good Morning/Afternoon Tumblrs!

“A team of experts recently re-created ancient Egypt’s most sought after perfumes, which may have been worn by the tragic monarch.

The idea of recreating Eau de Ancient Egypt was dreamed up by Robert Littman and Jay Silverstein of the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. For years, the archaeologists headed digs at a site called Tell-El Timai, which in ancient times was known as the city of Thmuis. It was also home to two of the most well-known perfumes in the ancient world, Mendesian and Metopian. “This was the Chanel No. 5 of ancient Egypt,”

Back in 2012, the archaeologists uncovered what was believed to be the home of a perfume merchant, which included an area for manufacturing some sort of liquid as well as amphora and glass bottles with residue in them.

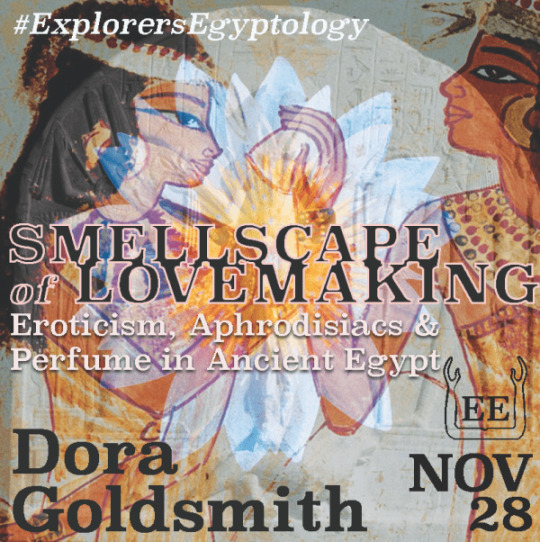

While the bottles did not smell, chemical analysis of the sludge did reveal some of the ingredients. The researchers took their findings to two experts on Egyptian perfume, Dora Goldsmith and Sean Coughlin, who helped to recreate the scents following formulas found in ancient Greek texts.

The basis of both of the recreated scents is myrrh, a resin extracted from a thorny tree native to the Horn of Africa and Arabian Peninsula. Ingredients including cardamom, olive oil and cinnamon were added to produce the ancient perfumes, which were, in general, much thicker and stickier than the stuff we spritz on today. In turn, the perfumes produced strong, spicy, faintly musky scents that tended to linger longer than modern fragrances.”

“Perfumer Mandy Aftel, who in 2005 helped reproduce a perfume used to scent a child mummy based on scrapings from a death mask, says it's up in the air whether Cleopatra really would have worn the same scent. It’s believed she had her own perfume factory and created signature scents instead of wearing what would be the relative equivalent of putting on a store-bought brand. In fact, there’s even a legend floating around claiming that she doused the sails of her royal ship in so much scent that Marc Antony could smell her coming all the way on shore when she visited him at Tarsus.”

“Smithsonian Institute-

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Queens of Egypt

Cleopatra and Nefertiti you know. But the ‘Queens of Egypt’ exhibition will blow you away with someone you’ve never heard of.

Many visitors to the National Geographic Museum’s “Queens of Egypt” will enter the exhibition knowing two names: Nefertiti and Cleopatra. But it’s the name Nefertari they’ll remember.

The legacy of this Egyptian queen is likely to blow your sandals off.

In fact, a pair of her sandals, on display here, is among the few artifacts that remain from Nefertari’s tomb, which was looted after her death in 1255 B.C. Yet her empty catacomb endured for centuries, until it was discovered in 1904. It’s one of the most spectacular ancient Egyptian archaeological sites ever unearthed.

The vivid way in which the museum evokes the tomb of Nefertari — the first wife of the pharaoh Ramses II — reflects this impressive exhibition. There’s a large model, made in the early 20th century, of Nefertari’s spectacularly decorated two-level catacomb. Adjacent to it, you’ll find a simulation of Nefertari’s final resting place, in a room that seems to spin around the viewer, via virtual-reality glasses.

Such high-tech media smartly supplements the show’s more conventional artifacts, which help evoke the ancient world. One room even features a video backdrop from an “Assassin’s Creed” game set in Egypt.

The historical objects come from five European and Canadian museums, with most of them on loan from Museo Egizio in Turin, Italy. Several items from that Italian archive are just as rare — if far more imposing — than that pair of sandals.

The show doesn’t attempt to cover all of Egypt’s known queens. Rather, it focuses on seven from the New Kingdom period, beginning with Ahmose-Nefertari (who reigned from 1539 to 1514 B.C.) and culminating with Cleopatra (technically known as Cleopatra VII).

The latter, who lost Egypt — and her life — to the Roman empire in 30 B.C., is billed as the “last” Egyptian queen, but her story is a bit more complicated than that. A descendant of Ptolemy I, a Macedonian Greek who established Hellenistic rule over Egypt in the late 4th century B.C., Cleopatra is not, strictly speaking, a successor to Hatshepsut, Nefertiti and the other Egyptian queens in this show.

Cleopatra is no stranger to modern eyes, having been depicted innumerable times in high and low culture, but few likenesses of her survive from her own time. One likely exception closes the show: a striking portrait bust from the Museo Egizio that has never been seen before in the United States. Three cobras sit on her head, symbolizing the three lands she meant to rule: Egypt, Syria — and Rome. (No wonder the Romans, after deposing her, destroyed every image of her they could find.)

“Queens of Egypt” maintains a careful balance between the exalted and the everyday. One display of jars contains ancient Egyptian-style perfumes, including Mendesian, which may have been Cleopatra’s favorite. Visitors can pop open the lid and take in the spicy scent.

Elsewhere, a corridor is lined with four large granite statues of Sekhmet, the lioness-faced war goddess. Other galleries reveal what life was like in a pharaoh’s harem, or in Deir El-Medina, a village that was home to the craftspeople who built and embellished the royal tombs. (The Greeks and Romans weren’t the only outsiders to overwrite Egyptian culture and language with their own; “harem” and “medina” are both Arabic terms.)

The workers of Deir El-Medina may have been commoners, but because of their trade, they were unusually well educated, leaving behind detailed records of their lives, inscribed on pottery or stone, and written on papyrus scrolls (some of which are on view here). One scroll featured in the show sheds light on the kind of conspiracies that were hatched in the harem: It’s a record of the trial of a wife of Ramses III, who plotted to overthrow the pharaoh and replace him with her son.

Of course, no tour of bygone Egypt would be complete without mummies. Just before you bid farewell to Cleopatra, you’ll find a grand chamber featuring 12 sarcophagi, arranged so that both container and contents can be seen. In a similar way, “Queens of Egypt” — whether through contemporary technology or millennia-old objects — illuminates its subject from the inside out.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The amphoras did not contain any noticeable smell — but they did contain an ancient dried residue (analysis of which is pending). Dora Goldsmith and Sean Coughlin replicated the Thmuis scent using formulas found in ancient Greek materia medica and other texts. Related Immortalizing Human Scents as Memory Perfumes Bodily odors are forever. Read more Both Mendesian and Metopian perfumes contain myrrh, a natural resin extracted from a thorny tree. The experts also added cardamom, green olive oil, and a little cinnamon—all according to the ancient recipe. The reproduced scent smells strong, spicy, and faintly of musk, Littman says. “I find it very pleasant, though it probably lingers a little longer than modern perfume.” In ancient Egypt, people used fragrance in rituals and wore scents in unguent cones, which were like wax hats that dripped oil into one’s hair over the course of the day. “Ancient perfumes were much thicker than what we use now, almost like an olive oil consistency,” Littman says. On the left, a musician wears an unguent cone. On the left, a musician wears an unguent cone. British Museum/Public Domain Though the modern-day Mendesian offers an intriguing approximation of an ancient Egyptian perfume, the jury’s out on whether Cleopatra would have worn it. “Cleopatra made perfume herself in a personal workshop,” says Mandy Aftel, a natural perfumer who runs a museum of curious scents in Berkeley, California. “People have tried to recreate her perfume, but I don’t think anybody knows for sure what she used.” Aftel is no stranger to the concocted scents of ancient Egypt. In 2005, she reproduced the burial fragrance of a 2,000-year-old mummified Egyptian child, a girl dubbed Sherit. Since her mummification, the perfume had shriveled into a thick black tar around Sherit’s face and neck, according to a Stanford press release. Aftel identified frankincense and myrrh as the primary ingredients in the perfume and reconstructed a copy. “I smelled the mummy,” Aftel says. “As a natural perfumer, it’s a very beautiful way to connect to the past.” If you’re in D.C., you can smell this most recent recreation yourself: the scent is on display at the National Geographic Museum’s exhibition “Queens of Egypt” until September 15. There’s not enough perfume to coat an entire sail, but you can dab a little on your arm.

https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/cleopatras-ancient-perfume-recreated

0 notes

Photo

The Making of Lotus Perfume Limestone slab with relief depicting women pressing lotus flowers. For the production of perfumes or narcotics. The women at center twist a sack in which the lotus flowers are collected, the juice of which collects in the container below. The Ancient Egyptians loved beautiful fragrances. They associated them with the gods and recognized their positive effect on health and well being. Perfumes were generally applied as oil-based salves, and there are numerous recipes and depictions of the preparation of perfume in temples all over Egypt. The most highly prized perfumes of the ancient world came from Egypt. The most popular were Susinum (a perfume based on lily, myrrh, cinnamon), Cyprinum (based upon henna, cardamom, cinnamon, myrrh and southernwood) and Mendesian (myrrh and cassia with assorted gums and resins). The god of perfume, Nefertem, was also a god of healing who was said to have eased the suffering of the aging sun god Ra with a bouquet of sacred lotus. Late Period, ca. 664-332 BC. Now in the Egyptian Museum of Turin. Cat. 1673 #egyptology_misr #Egypte #Agypten #Egipt #Egipto #Egitto #Египет #مصر #मिस्र #エジプト #埃及 #Egypten #Visit_Egypt #discover_Egypt #Experience_Egypt #diving #socialmedia #egypt #iloveegypt #luxor #karnak #mylifesamovie #mylifesatravelmovie #travelblog #travelblogger #solotravel #wanderlust #gopro #egyptology #ancientegypt (at Egyptian Museum) https://www.instagram.com/p/B2joddohnZZ/?igshid=189ei8b8qw0qy

#egyptology_misr#egypte#agypten#egipt#egipto#egitto#египет#مصر#म#エジプト#埃及#egypten#visit_egypt#discover_egypt#experience_egypt#diving#socialmedia#egypt#iloveegypt#luxor#karnak#mylifesamovie#mylifesatravelmovie#travelblog#travelblogger#solotravel#wanderlust#gopro#egyptology#ancientegypt

0 notes

Text

Cleopatra May Have Once Smelled Like This Recreated Perfume

https://sciencespies.com/history/cleopatra-may-have-once-smelled-like-this-recreated-perfume/

Cleopatra May Have Once Smelled Like This Recreated Perfume

Cleopatra VII, the last ruler of Egypt before the Romans took power, has been described as both beautiful and not so beautiful in ancient histories. The coins and busts produced of her seem to be a mixed bag as well. But while we may never really know what she looked like, archaeologists may have figured out what she smelled like. That’s right—a team of experts recently re-created ancient Egypt’s most sought after perfumes, which may have been worn by the tragic monarch.

The idea of recreating Eau de Ancient Egypt was dreamed up by Robert Littman and Jay Silverstein of the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. For years, the archaeologists headed digs at a site called Tell-El Timai, which in ancient times was known as the city of Thmuis. It was also home to two of the most well-known perfumes in the ancient world, Mendesian and Metopian. “This was the Chanel No. 5 of ancient Egypt,” Littman puts it in an interview with Sabrina Imbler at Atlas Obscura.

Back in 2012, the archaeologists uncovered what was believed to be the home of a perfume merchant, which included an area for manufacturing some sort of liquid as well as amphora and glass bottles with residue in them.

While the bottles did not smell, chemical analysis of the sludge did reveal some of the ingredients. The researchers took their findings to two experts on Egyptian perfume, Dora Goldsmith and Sean Coughlin, who helped to recreate the scents following formulas found in ancient Greek texts.

The basis of both of the recreated scents is myrrh, a resin extracted from a thorny tree native to the Horn of Africa and Arabian Peninsula. Ingredients including cardamom, olive oil and cinnamon were added to produce the ancient perfumes, which were, in general, much thicker and stickier than the stuff we spritz on today. In turn, the perfumes produced strong, spicy, faintly musky scents that tended to linger longer than modern fragrances.

“What a thrill it is to smell a perfume that no one has smelled for 2,000 years and one which Cleopatra might have worn,” Littman says in a university press release.

Perfumer Mandy Aftel, who in 2005 helped reproduce a perfume used to scent a child mummy based on scrapings from a death mask, says it’s up in the air whether Cleopatra really would have worn the same scent. It’s believed she had her own perfume factory and created signature scents instead of wearing what would be the relative equivalent of putting on a store-bought brand. In fact, there’s even a legend floating around claiming that she doused the sails of her royal ship in so much scent that Marc Antony could smell her coming all the way on shore when she visited him at Tarsus.

Even if Cleopatra didn’t wear the stuff, it’s likely the elite in the ancient world did wear something that smells similar to the recreated perfumes. Currently, we mere peasants can get a whiff of the ancient scents at the National Geographic Society’s “Queens of Egypt” exhibit, running through mid-September.

#History

0 notes

Text

If you're interested in ancient Egypt, I carry two perfume oils that have been around for thousands of years. Worn by any gender, they last longer than alcohol based perfumes. And you get to support a disabled autistic witch! Win win!

https://www.etsy.com/shop/BeanNoneya

#cleopatra #Egypt #ancientegypt #ancientegyptian #ancientegyptians #perfumeoil #cleopatrasperfume #actuallyautistic #autist #autisticadult #asd #adhd #audhd #specialinterest #scent #scentscience #archeologyexperiment #archeology #egyptianarchaeology #natrualist #olfactory #olfactorystimming #smellscape #olfactoryhistory #mendesian #witch #witchy #alchemy #perfumeoil #perfume

#mendesian#cleopatra#cleopatrasperfume#egyptology#scent#scentscience#perfumeoil#ancientegyptianperfume#ancientegypt#ancientscent#autisticcreator#autisticadult#autist#audhd#adhd#smallhouseperfumer#smallbatchperfume#scentscape#oneofakind

63 notes

·

View notes

Photo

...The most highly prized #perfumes of the #ancient world came from Egypt. Of these, arguably the most popular were Susinum (a perfume based on lily, myrrh, cinnamon), Cyprinum (based upon henna, cardamom, cinnamon, myrrh and southernwood) and Mendesian (myrrh and cassia with assorted gums and resins). Mendesian was named after the ancient city of Mendes, and although the #perfume was produced in other locations at a later date, the best variety was still thought to be that from Mendes... . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . #saprilhashtag #perfumery #creation #create #creator #perfumer #perfumesales #perfumebusiness #natura #beauty #women #scents #fragrancearmy #fragancias #eaudeparfum #cologne #fragranceoftheday #olfactory #perfumehouse #perfumersworld https://www.instagram.com/p/BvubKXoA8yv/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=1su2p4kcaplzm

#perfumes#ancient#perfume#saprilhashtag#perfumery#creation#create#creator#perfumer#perfumesales#perfumebusiness#natura#beauty#women#scents#fragrancearmy#fragancias#eaudeparfum#cologne#fragranceoftheday#olfactory#perfumehouse#perfumersworld

0 notes

Photo

The Making of Lily Perfume The Ancient Egyptians loved beautiful fragrances. They associated them with the gods and recognized their positive effect on health and well being. Perfumes were generally applied as oil-based salves, and there are numerous recipes and depictions of the preparation of perfume in temples all over Egypt. The most highly prized perfumes of the ancient world came from Egypt. The most popular were Susinum (a perfume based on lily, myrrh, cinnamon), Cyprinum (based upon henna, cardamom, cinnamon, myrrh and southernwood) and Mendesian (myrrh and cassia with assorted gums and resins). The god of perfume, Nefertem, was also a god of healing who was said to have eased the suffering of the aging sun god Ra with a bouquet of sacred lotus. Relief depicting women squeezing oil from lily flowers in a press for use in perfume. Fragment from a decoration of a tomb. Limestone, 4th century BC. Now in the Louvre. E 11162 #egyptology_misr #Egypte #Agypten #Egipt #Egipto #Egitto #Египет #مصر #मिस्र #エジプト #埃及 #Egypten #Visit_Egypt #discover_Egypt #Experience_Egypt #diving #socialmedia #egypt #iloveegypt #luxor #karnak #mylifesamovie #mylifesatravelmovie #travelblog #travelblogger #solotravel #wanderlust #gopro #egyptology #ancientegypt (at Musée du Louvre) https://www.instagram.com/p/B2NZavnFN1W/?igshid=4shoiophev0j

#egyptology_misr#egypte#agypten#egipt#egipto#egitto#египет#مصر#म#エジプト#埃及#egypten#visit_egypt#discover_egypt#experience_egypt#diving#socialmedia#egypt#iloveegypt#luxor#karnak#mylifesamovie#mylifesatravelmovie#travelblog#travelblogger#solotravel#wanderlust#gopro#egyptology#ancientegypt

0 notes

Text

Cleopatra May Have Once Smelled Like This Recreated Perfume

https://sciencespies.com/history/cleopatra-may-have-once-smelled-like-this-recreated-perfume/

Cleopatra May Have Once Smelled Like This Recreated Perfume

Cleopatra VII, the last ruler of Egypt before the Romans took power, has been described as both beautiful and not so beautiful in ancient histories. The coins and busts produced of her seem to be a mixed bag as well. But while we may never really know what she looked like, archaeologists may have figured out what she smelled like. That’s right—a team of experts recently re-created ancient Egypt’s most sought after perfumes, which may have been worn by the tragic monarch.

The idea of recreating Eau de Ancient Egypt was dreamed up by Robert Littman and Jay Silverstein of the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. For years, the archaeologists headed digs at a site called Tell-El Timai, which in ancient times was known as the city of Thmuis. It was also home to two of the most well-known perfumes in the ancient world, Mendesian and Metopian. “This was the Chanel No. 5 of ancient Egypt,” Littman puts it in an interview with Sabrina Imbler at Atlas Obscura.

Back in 2012, the archaeologists uncovered what was believed to be the home of a perfume merchant, which included an area for manufacturing some sort of liquid as well as amphora and glass bottles with residue in them.

While the bottles did not smell, chemical analysis of the sludge did reveal some of the ingredients. The researchers took their findings to two experts on Egyptian perfume, Dora Goldsmith and Sean Coughlin, who helped to recreate the scents following formulas found in ancient Greek texts.

The basis of both of the recreated scents is myrrh, a resin extracted from a thorny tree native to the Horn of Africa and Arabian Peninsula. Ingredients including cardamom, olive oil and cinnamon were added to produce the ancient perfumes, which were, in general, much thicker and stickier than the stuff we spritz on today. In turn, the perfumes produced strong, spicy, faintly musky scents that tended to linger longer than modern fragrances.

“What a thrill it is to smell a perfume that no one has smelled for 2,000 years and one which Cleopatra might have worn,” Littman says in a university press release.

Perfumer Mandy Aftel, who in 2005 helped reproduce a perfume used to scent a child mummy based on scrapings from a death mask, says it’s up in the air whether Cleopatra really would have worn the same scent. It’s believed she had her own perfume factory and created signature scents instead of wearing what would be the relative equivalent of putting on a store-bought brand. In fact, there’s even a legend floating around claiming that she doused the sails of her royal ship in so much scent that Marc Antony could smell her coming all the way on shore when she visited him at Tarsus.

Even if Cleopatra didn’t wear the stuff, it’s likely the elite in the ancient world did wear something that smells similar to the recreated perfumes. Currently, we mere peasants can get a whiff of the ancient scents at the National Geographic Society’s “Queens of Egypt” exhibit, running through mid-September.

#History

0 notes