#jung hawon

Text

« Known globally for highly stylized genre films depicting the gritty underbelly of society with brutal violence and crimes, South Korean cinema was long characterized by what one film critic famously called “dark blue filter thrillers” mostly made by and starring men. If women appeared at all, it was often as one-dimensional clichés, serving as plot devices like a femme fatale, a murder or rape victim, an innocent lover or wife, or a self-sacrificing mother.

To challenge this norm and support women filmmakers, some women started to not only watch female-driven films but also buy more tickets than they could even use for such movies in a campaign called “spirit-sending”— meaning they would be at the theaters in spirit. The campaign turned a surefire box-office disaster to an award-winning hit, saving the career of a rare female director.

“It was truly a miracle,” Lee Ji-Won said of Miss Baek, her 2018 debut film about a female former convict trying to save a little girl from abusive parents. The drama, which portrays the friendship between two abuse survivors, was such a rarity in an industry dominated by what Lee called “films with cops, gangsters, naked women, or rom-coms” that it was snubbed by almost all investors and distributors. One investor promised to fund it only if Lee changed the lead character to a man. Another bet that “the disaster-in-waiting” would perish in cinemas in a week—a warning that almost materialized, as the film’s opening-day sales were so poor that it was projected to sell less than a quarter of the tickets required just to break even.

“Everybody, myself included, was so sure that the movie would crash and burn, and my career was over—until weird things started to happen on social media,” Lee told me.

Impressed by the rare women-led film with complex female characters, made by an even rarer woman director, many women watched it again and again, buying tickets even when they couldn’t attend. Ticket sales rebounded sharply as #SendingSpirit became a viral hashtag that continued for months until the film broke even. Miss Baek eventually won rave reviews and swept major awards, and the same investors who’d once snubbed Lee began to court her, begging to see her scripts.

“The gesture of solidarity by all these women was just overwhelming,” Lee said, wiping away tears. “They, like me, were so thirsty for movies portraying women as complex, multidimensional human beings.” In 2021, she finished shooting her second movie, featuring some of the country’s biggest stars.

The “spirit-sending” campaign lived on to drive the success of other

women-led movies, like the film adaptation of Kim Ji-Young, Born 1982, allowing such films to defy the boycott campaigns that often targeted “feminism-stained movies.” While the film was hit by thousands of 0 percent ratings even before its official release (causing a vast gender disparity in its ratings on the top web portal—2.99 among men and 9.45 among women), Kim Ji-Young eventually became a hit watched by millions at home. Female-driven movies have grown in numbers and ticket sales since, led by a new generation of filmmakers like Lee and some male filmmakers as well. »

— Hawon Jung, Flowers of Fire: The Inside Story of South Korea's Feminist Movement

108 notes

·

View notes

Text

Men can either evolve or die alone. The women in this movement may not have a spouse or kids but they are building their own community

Many South Korean women are so fed up with machismo that, in recent years, they’ve taken up a radical stance: refusing to marry, date men, have sex and reproduce. This movement—known as “the four no’s”—began in 2019. It has since spread, in the hope that the conservative government of Yoon Suk-yeol will adopt measures that promote gender equality.

Despite the solid academic credentials of women in South Korea, according to a study by Statista, the gender pay gap is scandalous: men earn 30% more than women. This makes the country, according to the Korean Herald, the most gender-unequal OECD nation.

Added to this is a poor work-life balance in South Korea, as well as a disparity in the distribution of domestic tasks. Women often assume the responsibility of raising children, pushing them to have to choose between working or being mothers. In South Korea, the work week is 52-hours-long.

The ”four no’s” is a desperate cry that arose after the incumbent South Korean president began his term. He has stated his intention to abolish the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family. The repercussions of the so-called “birth strike” have been severe for the country. For three consecutive years, the country has had the lowest fertility rate in the world, with an average of 0.78 children per woman.

“Life isn’t going well for many young people, for whom getting married or having children is no longer natural,” Lee Sang-lim, a demographer at the Korea Institute of Health and Social Affairs, told The New York Times.

The country is on alert, since an average of 2.1 children per woman is estimated to be necessary to keep the population stable. In 2020, the number of deaths exceeded the number of births in South Korea. Many cities are at risk of disappearing in the coming years.

Hawon Jung, the author of Flowers of Fire: The Inside Story of South Korea’s Feminist Movement, tells EL PAÍS that the movement was sparked by the governmental policies in a country that she considers to be very conservative.

“Single mothers are stigmatized, doctors refuse to give IVF to women without a male partner—even though it’s not illegal—and out-of-wedlock births represent only 2% of the total, compared to the average of 41% for women in the OECD. Marriage and childbirth are closely intertwined; women are pressured to sacrifice their career once they have a child or get married.”

Jung believes that the origin of the problem lies in the role of women since Confucianism—the prevailing ideology before the reforms of the 20th century. The philosophy advocated submissive daughters, chaste wives and self-sacrificing mothers. These beliefs were maintained due to a militarized society, where the concept of aggressive masculinity has been prevalent throughout history. This has applied from the Korean War (1950-1953) onwards, through the military dictatorship, to the ongoing confrontation with North Korea.

According to Jung, “countries where parents are more cooperative and have good family policies—such as Sweden—or that recognize the diversity of couples, like France, have been more successful in stabilizing or even increasing their birth rates.”

The movement of the “four no’s” reflects the radicalization of a frustration that has made women even opt to give up sex. According to Jung, “young women don’t consider it worth investing their time and energy into having affairs with men,” as they find it exhausting trying to find one who doesn’t follow patriarchal norms.

Feminist movements have, historically, been very effective in the country, achieving milestones such as the decriminalization of abortion in 2021, or changes in the notions of female beauty. The “escape of the corset” movement, for instance, rejects the rigid South Korean stereotypes associated with women, such as having long hair or following the K-pop beauty concept, which imposes the obligation on women to have porcelain skin, wear perfect makeup and undergo plastic surgery. It’s increasingly common to see South Korean women and girls with short hair, or daring to wear glasses rather than contact lenses. This has been a real revolution.

But there is still a long way to go in a country where gender violence doesn’t always lead to a charge or divorce. According to a survey published by the Korean Institute of Criminology and Justice, eight out of 10 men admitted to having been violent towards their partner.

Jennifer Jung-Kim, a professor of Korean History at UCLA, points out via email that, in order to solve the problems derived from the gender gap in South Korea, gender-based violence must be recognized and prosecuted as such.

“When it comes to the government and corporations, laws and policies must prohibit discrimination and guarantee equal pay and opportunities for women… especially working mothers. Socially, there needs to be a greater support system for working parents, so that either parent can take days off if a child is sick, or to attend a school meeting or event. And single parents, whether male or female, shouldn’t be stigmatized, regardless of whether they are adoptive or biological parents,” she explains.

For Jung-Kim, the most important thing is an internal change on the part of men.

“They must step up and take on household chores and childcare equally and support their wives in their career choices.”

Judy Han, a professor and vice chair of Undergraduate Affairs in the Department of Gender Studies at UCLA, points out that the movement of the “four no’s” is an invitation to rebuild society.

“Can we imagine a world where women don’t have to shoulder the full burden of reproductive and domestic work, without being degraded or exploited? Where they could have marriage equality without throwing away their professional careers? Can women imagine a world without abuse, rape and violence?” she wonders.

This approach could work in many other democratic countries where gender inequality affects birth rates. Faced with an apparently unbeatable patriarchal system, more and more women around the world are choosing to give up having children, because they cannot reconcile their personal and professional lives. The consequences can push governments to act and shape entire societies.

According to Judy Han, “anyone—men and women, straight, queer, cisgender and transgender—would benefit from taking these criticisms seriously and creating a more just society.”

#South Korea#the Four No’s#No dates#no sex#no weddings#No kids#Hawon Jung#Flowers of Fire: The Inside Story of South Korea’s Feminist Movement

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

#books#history#feminism#politics#nonfiction#flowers of fire#hawon jung#aviva wei xue#kate rose#weibo feminism

0 notes

Text

#books#history#feminism#hawon jung#flowers of fire#aviva wei xue#kate rose#weibo feminism#politics#nonfiction

1 note

·

View note

Text

dan malah aku yang menyadarinya Hh~

0 notes

Text

៹ ♡. 𝗺𝘂𝘀𝗲 › meet the kids xvi

#៹ ♡. 𝗺𝘂𝘀𝗲 › olav dahl-kang#៹ ♡. 𝘀𝗵𝗶𝗽 › eunju + olav / elav#៹ ♡. 𝗺𝘂𝘀𝗲 › ophelia bak#៹ ♡. 𝘀𝗵𝗶𝗽 › ophelia + kai#៹ ♡. 𝗺𝘂𝘀𝗲 › park jieun#៹ ♡. 𝘀𝗵𝗶𝗽 › jaejoong + jieun / jieung#៹ ♡. 𝗺𝘂𝘀𝗲 › park seoyeon#៹ ♡. 𝘀𝗵𝗶𝗽 › ezra + seoyeon / seora#៹ ♡. 𝗺𝘂𝘀𝗲 › park siwon#៹ ♡. 𝘀𝗵𝗶𝗽 › hayi + siwon / hawon#៹ ♡. 𝗺𝘂𝘀𝗲 › park 'suzy' suji#៹ ♡. 𝘀𝗵𝗶𝗽 › dongyul + suzy / songyul#៹ ♡. 𝗺𝘂𝘀𝗲 › piper jung-johnson#៹ ♡. 𝘀𝗵𝗶𝗽 › federico + piper / chung#៹ ♡. 𝗺𝘂𝘀𝗲 › poliana hwang#៹ ♡. 𝗺𝘂𝘀𝗲 › pyo sandara#៹ ♡. 𝘀𝗵𝗶𝗽 › sandara + sungho / sundara#៹ ♡. 𝗺𝘂𝘀𝗲 › reyna mori#៹ ♡. 𝘀𝗵𝗶𝗽 › minhyuk + reyna / reyuk#tag dump

0 notes

Text

My top 10 nonfiction reads of 2023 (the asterisked ones are in French with no translation as of yet) :

Belle Greene, Alexandra Lapierre

The Indomitable Marie-Antoinette, Simone Bertière

Reporter: A Memoir, Seymour Hersh

Red Carpet: Hollywood, China and the Global Battle for Cultural Supremacy, Erich Schwartzel

Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Dynasty, Patrick Keefe

Servir les riches, Alizée Delpierre*

La Comtesse Greffulhe : L’ombre des Guermantes, Laure Hillerin*

Le Courage de la nuance, Jean Birnbaum*

The Book Collectors of Daraya, Delphine Minoui

Flowers of Fire: The Inside Story of South Korea's Feminist Movement, Hawon Jung

#book recs#i haven't finished the last one yet but it's been good so far! i really admire these women's resilience and solidarity#some inspiring stories of political activism + insight into aspects of korean history i didn't know about#i wanted to do a half-fiction half-nonfiction list like last year but i've read mostly disappointing fiction this year :(#my favourites were probably kivirähk's the man who spoke snakish & catherynne valente's radiance; though it wasn't as good as orphan tales#i'm reading jacques abeille's les jardins statuaires right now and it's quite frustrating because on the one hand#it's well-written and interesting with original worldbuilding. on the other i'm 300 pages in and there have been#2 female characters. the purpose of both (so far) was to have sex with the male protagonist and only 1 has a name#which makes the read feel less original and more ''same old shit as far as i'm concerned''

266 notes

·

View notes

Text

By Hawon Jung

After trying for over a year to persuade more South Korean women to have babies, Chung Hyun-back says one reason stands out for her failure: “Our patriarchal culture.” Ms. Chung, who was tasked by the previous government with reversing the country’s plummeting birthrate, knows firsthand how tough it is to be a woman in South Korea. She chose her career over nuptials and children. Like her, millions of young women have been collectively spurning motherhood in a so-called birth strike.

A 2022 survey found that more women than men — 65 percent versus 48 percent — don’t want children. They’re doubling down by avoiding matrimony (and its conventional pressures) altogether. The other term in South Korea for birth strike is “marriage strike.”

The trend is killing South Korea. For three years in a row, the country has recorded the lowest fertility rate in the world, with women of reproductive age having fewer than one child on average. It reached the “dead cross,” when deaths outnumbered births, in 2020, nearly a decade earlier than expected.

Chung Hyun-back, who was South Korea’s gender equality minister in 2017-18, tried unsuccessfully to raise the country’s plunging fertility rate. Among the obstacles she says are to blame is the country’s “patriatchal culture."

Now, about half of the country’s 228 cities, counties and districts risk losing so many residents they might vanish. Day care centers and kindergartens are being converted into nursing homes. Ob-Gyn clinics are closing, and funeral parlors are opening. At Seoksan Elementary School, in rural Gunwi County, the student body has shrunk from 700 pupils to four. When last I visited, the children couldn’t even form a soccer team.

Young Koreans have well-documented reasons not to start a family, including the staggering costs of raising children, unaffordable homes, lousy job prospects and soul-crushing work hours. But women in particular are fed up with this traditionalist society’s impossible expectations of mothers. So they’re quitting.

President Yoon Suk-yeol, elected last year, has suggested feminism is to blame for blocking “healthy relationships” between men and women. But he’s got it backward — gender equality is the solution to falling birthrates. Many of the Korean women shunning dating, marriage and childbirth are sick of pervasive sexism and furious about a culture of violent chauvinism. Their refusal to be “baby-making machines,” according to protest banners I’ve seen, is retaliation. “The birth strike is women’s revenge on a society that puts impossible burdens on us and doesn’t respect us,” says Jiny Kim, 30, a Seoul office worker who’s intent on remaining childless.

Making life fairer and safer for women would work wonders toward reducing the country’s existential threat. Yet this feminist dream seems increasingly far-fetched, as Mr. Yoon’s conservative government champions regressive policies that only magnify the problem.

South Korea’s demographic crisis was once inconceivable: As late as the 1960s, women had six children on average. But the state, pursuing economic development, carried out an aggressive population control campaign. In about 20 years, women were having fewer than the 2.1 children needed for replenishment, a number that’s only continued to drop. The latest available data from South Korea’s statistics agency put the fertility rate at 0.81 for 2021; by the third quarter of 2022 it was 0.79.

Recent governments have indeed been alarmed by a rate that’s seemingly approaching zero. Over 16 years, 280 trillion won ($210 billion) has been poured into programs encouraging procreation, such as a monthly allowance for parents of newborns.

Many women still say nope. No wonder. There’s little escaping suffocating gender norms, whether in pregnancy guidelines to arrange clean undergarments for your husband before labor, or the dayslong kitchen drudgework for holidays like the Chuseok harvest festival. Married women are saddled with the lion’s share of chores and child care, squeezing new mothers so much that many give up professional ambitions. Even in dual-income households, wives daily spend more than three hours on these tasks versus their husband’s 54 minutes.

Discrimination against working mothers by employers is also absurdly common. In one notorious case, the country’s top baby formula maker was accused of pressuring female employees to quit after getting pregnant.

And gender-based violence is “shockingly widespread,” according to Human Rights Watch. In 2021, a woman was murdered or targeted for murder every 1.4 days or less, according to the Korea Women’s Hotline. Women have dubbed the act of ending a relationship without getting a vicious reaction a “safe breakup.”

But women haven’t passively accepted the toxic masculinity. They’ve organized raucously, from Asia’s most successful #MeToo movement to groups like “4B,” which translates to the “Four nos: no dating, no sex, no marriage and no child-rearing.” The country’s feminist movements have won the decriminalization of abortion and harsher penalties for an epidemic of spycam-porn crimes.

Many young Korean men, however, have declared themselves victims of women’s activism. President Yoon rose to power last year by leveraging this resentment. He echoed the dog whistle of men’s rights advocates, declaring that structural sexism no longer exists in South Korea and vowing tougher punishment for false reports of sexual assault.

Mr. Yoon’s government is removing the term “gender equality” from school textbooks and has canceled funding for programs to fight everyday sexism. “If you find gender equality and feminism so important, you can do it with your own money and time,” said one lawmaker in his party.

The government is also working to dismantle its own headquarters for women’s empowerment — the gender equality ministry. Established in 2001, it’s been transformative in normalizing parental leave for fathers and helping more women achieve workplace seniority.

Comments by the gender equality minister under the Yoon administration illustrate its abandonment of women. In September, Kim Hyun-sook rejected the idea that misogyny was at play when a Seoul Metro worker stabbed a female colleague to death in a subway bathroom after stalking her for years. Ms. Kim also initially declared that the rape and killing of a college student on campus last June was not violence against women and shouldn’t be used to fan “gender conflict.”

So far, none of the measures implemented by successive governments have flipped the trends in marriage and childbearing. Worse yet, the current government seems to be actively undermining efforts that gave women hope. “This is a historical regression,” says Ms. Chung, who was the gender equality minister from 2017 to 2018. Society can’t end the birth strike without acknowledging women’s grievances, she says.

Motivating Korean women to reconsider marriage and children involves infusing every aspect of their lives with agency and equality. A feminist approach would remove obstacles to motherhood simply by enforcing existing laws against workplace discrimination. It would destigmatize births outside of marriage and make domestic duties everyone’s responsibility. It would condemn gender violence as reprehensible. A feminist approach would admit there’s a systemic problem.

It’s clear that countries with a disproportionate division of child care or lacking national paid parental leave, like Japan and the United States, also have plunging fertility rates. It’s the same with China, where women inspired by South Korea started their own “Four nos” movement; government data this month reveals its population is shrinking, too. But countries with cooperative fathers and good family policies, like Sweden, or that recognize diverse companionships, like France, have been more successful at stabilizing or even bumping up births.

The United Nations projects that South Korea’s 51 million population will halve before the end of the century. Survival of the nation is at stake.

Hawon Jung (@allyjung) is the author of the forthcoming “Flowers of Fire: The Inside Story of South Korea’s Feminist Movement and What It Means for Women’s Rights Worldwide,” and a former Agence France-Presse reporter in Seoul. She splits her time between South Korea and Germany.

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

Korea's 4B Movement: Real Radical Women

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

나는솔로 93회 다시 보기 93화 E93 ((2304019)) SBS

나는솔로 93회 다시 보기 93화 E93 ((2304019)) SBS <<

나는솔로 93회 다시 보기 93화 E93 ((2304019)) SBS

나는솔로 93회 다시 보기 93화 E93 ((2304019)) SBS

나는솔로 93회 다시 보기 93화 E93 ((2304019)) SBS

나는솔로 93회 다시 보기 93화 E93 ((2304019)) SBS

나는솔로 93회 다시 보기 93화 E93 ((2304019)) SBS

Anyway, in order to make the sea route safe, he was also eager to clear up pirates, which was the original purpose, and it is recorded in the Samguk Sagi that the Silla slave trade almost disappeared thanks to Jang Bo-go's performance. do. In 838, in the pilgrimage to Ipdang-gu, Ennin [31], who was considered the best monk in Japan at the time, even though the Japanese went to China without going through Silla, they hired Silla interpreters Kim Jeong-nam and Park Jung-jang, etc. Silla's maritime influence had grown to such an extent that each ship was assigned to accompany them. This is because most of the Chinese coastal areas were also active in large numbers during this period. Even after that, Ennin asked Jang Bo-go to protect him so that he could safely finish his schedule during Tang Dynasty activities.

In addition, Jang Bo-go built a temple called Jeoksan Beophwawon in the Shandong Peninsula, and it is said that monks from Silla and Japan stayed here.[32] It is said that this Jeoksan Beophwawon was run by Jangyeong and other Silla people, and they were in charge of gathering the re-dang Silla people by holding regular Buddhist meetings. It seems to have played a role similar to that of the Korean church in modern Koreatown. Jeoksan Beophwawon is presumed to have disappeared during the extensive suppression of Buddhism during the Tang Dynasty, but it has been restored and remains in China. On the other hand, it is presumed that Jang Bo-go also established Beophwawon in Cheonghae-jin and Hawon-dong, Seogwipo-si, Jeju-do. It is unknown what kind of Buddhist ceremony was held here because the records are not detailed, but the fact that the Amitabha triad was enshrined suggests that it was related to the Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva faith. Members of Sillabang society were mostly occupations closely related to the sea, and the relationship between the people of the sea and the faith of Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva at the time can be confirmed in the Minjangsa section of the Samguk Yusa.

In addition, the above-mentioned Ennin accurately recorded the help of Jang Bo-go in his travelogue called 《Ipdanggubeop Pilgrimage》[33]. Thanks to this, the portrait of Jang Bo-go holding a bow is still at Jeoksan Seonwon in Mt. Hiei, Kyoto, Japan. He was a very international figure in the East Asian world at the time, as his achievements and reputation crossed Korea, China and Japan.

Jang Bo-go frequently dispatched instructor ships to the Tang Dynasty, remotely controlled the Sillabang society on the east coast of the Tang Dynasty, and was able to gain huge trade profits by utilizing it. According to Ennin's diary, on June 27, 839, two instructor ships sent by Jang Bo-go arrived at Jeoksanpo, and it was said that a person named Choi Hun-sip-rang, who had the title of Cheonghae-jin soldier, was trained as Maemulsa[34]. Hoon Choi's schedule stopped at Jeoksan Court House[35] to comfort Jang Young, who was managing Jang Bogo on behalf of Bogo, and for seven and a half months, he stopped at major ports on the east coast of China, such as Yusanpo, Haeju, Choju, and Yangju, to carry out trade activities. It was to return to the enemy cannon. It is estimated that Jeoksanpo was the main base for the Chinese side of the Jang Bogo trade ship.

Jang Bo-go periodically dispatched a trading fleet called Hoe-sa to Japan in the east. The Hoe-sa was only a trade fleet personally sent by Jang Bo-go, but it was so large that it resembled an official envoy, so it was Japan's official foreign trade at the time. Dazaifu [36] in Kyushu, which served as a window, argued that they should be expelled instead of accepting the company history.

0 notes

Photo

"Women in South Korea Are on Strike Against Being ‘Baby-Making Machines’" by Hawon Jung via NYT Opinion https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/27/opinion/south-korea-fertility-rate-feminism.html?partner=IFTTT

0 notes

Text

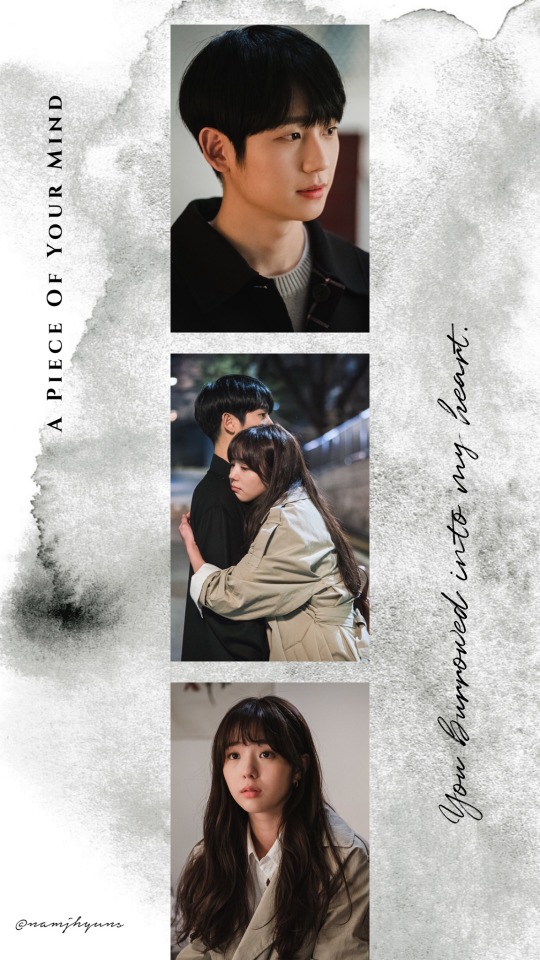

a piece of your mind

a piece of your mind

I remember watching this series like around two years ago. I tried to watch it in between the online meetings. And then today, when i was so bored, i watched it on TVN. I was hooked.

It started again, the feeling of enjoying this sad series. I mean i always find Jung Hae In as a cute man who could depicted Hawon’s character very well. Not to mention, Chae Soo Bin, who was succeeded in describing…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Cinderella and the Four Knights

NOTICE: THERE WILL BE SPOILERS IN THIS POST. PLEASE READ WITH CAUTION.

Where did I watch this?: Netflix

Show Genre: romance, comedy, light angst (angst is fanfic terms but idk how to describe it lol)

Show Warnings: Netflix says “fear” but I don’t think that counts...mentions of death

How many times did Sam cry?: not that many tbh, I’d say like twice (I’m very emotional)

Ratings

Plot: 5/10

Cast: 9/10

Ending: 7/10

Sam’s Overall Rating: 7.5/10

-------------------------

This show was honestly so good I was surprised. The storyline is pretty similar to Boys Over Flowers, but I still loved it!

I think it was pretty weird how Hyunmin was such an important character in the beginning, but it felt like he was shoved to the side a lot for Jiwoon. It would have been a lot better if they kept Hyunmin as a main lead, as well as Jiwoon. Also why did Seowoo not get nearly as much screentime?? It’s so sad, he’s an amazing character. I think Jiwoon's sudden feeling change between Hyeji and Hawon was pretty weird too, but I will say that I love Hawon as a character. She's such a strong and independent character.

I also thought the ending was pretty rushed, especially with trying to tie up all the loose ends with the whole “Cinderella” concept. I love the cast though, and I think that Park Sodam was a perfect actress to play Eun Hawon!

I do have a lot of questions about Yoonsung and the role his character is supposed to play, though. I understand why he did what he did in the show, and I do like how no matter what, he still stood up for the Kang family and the Haneul Group. I just don’t really get why they considered him the 4th knight? Like, yeah he protected Kang Hyunmin, Kang Jiwoon, Kang Seowoo and Eun Hawon, but I’m not sure that I would consider him a “knight” in the story as he never really was involved with the love,,,,triangle? square? that was going on between the Kang cousins, Hawon and Hyeji.

Overall, this show is absolutely amazing and I loved it, the ending is just what threw me off a bit, though I am glad it’s still a happy ending.

#cinderella and the four knights#kdrama recommendations#kdrama#kdrama review#boys over flowers#park sodam#jung il woo#ahn jae hyun#lee jungshin#choi min#son naeun#kang seowoo#kang jiwoon#kang hyunmin#eun hawon#korean drama#kdrama couple#kdrama commentary

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Piece of Your Mind will go down in Dramaland’s history as a criminally underrated masterpiece. So, I decided to make some lockscreens for everyone who loves the drama as much as I do.

Reblog if use and enjoy~🌸

Please, don’t remove the credit.

#a piece of your mind#kdrama#jung hae in#chae soo bin#park joo hyun#kim jeong woo#mine#my edit#hawon and seowoo forever#lockscreens#namjhyun#a piece of your mind lockscreens

141 notes

·

View notes

Text

★ kdramas icons ★

like or reblog.

#he is psychometric#shin yeun#yoon jaein#park sodam#cinderella and the four knights#yoon siwon#yook dongsik#chocolate#yoon kyesang#lee kang#park jinyoung#lee an#psychopath diary#he is psychometric icons#shin yeun icons#yoon jaein icons#jung ilwoo icons#park sodam icons#cinderella and four knights icons#eun hawon icons#yoon siwon icons#yook dongsik icons#chocolate icons#yoon kyesang icons#lee kang icons#park jinyoung icons#lee an icons#psychopath diary icons#doramas icons#kdramas icons

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

🌱 — a piece of your mind: seo woo & ha won

© dramaurora

.

📎 like or reblog if you save/use, please!

#a piece of your mind#apoym#반의 반#seo woo#seowoo#han seo woo#chae soobin#soobin#채수빈#hawon#ha won#moon ha won#jung haein#haein#정해인#kdrama#korean drama#korean drama icons#dorama#dorameira#asian drama#asian drama icons#icons kdrama#kdrama icons#icons doramas

5 notes

·

View notes