#jonah IS easy to root for!! but just because we as an audience see that doesn’t mean amy should drop everything and run to him right away

Text

No, because the thing is, 911 has 3 established main couples, 2 we see them getting together, bathena and madney, and the other is introduced to us already established, henren are already married when we get introduced to Karen. But an interesting thing there for me, is that Karen is introduced to us while Hen does something that most people find unforgivable, cheating, which makes us sympathize with Karen even though Karen technically only exists to be Hen's wife, so even tho the audience is usually biased towards the main character, we end up caring about Karen more, which makes it so even though she only exists through Hen, we like her, we like them together. Madney and Bathena on the other hand work because they exist individually, we care about all four of them, the relationship is an extra point for the character, it's not why they're there, so it works because we are not heavily biased in any direction. And that's the thing that makes me question what's going on with the love interests for Buck and Eddie. Ali barely existed for us but there's a really heavy point against her with the whole not being able to deal with Buck's job. Taylor is right off the bat introduced to us as someone who will use anything to get on top, including wanting to capitalize on Bobby's addiction, so we always end up suspicious of her because she was willing to hurt a character we care about for her own gain, so she never really had a chance, she only exists through Buck, and she already hurt someone else, so most of us don't care that Buck cheated on her and we're not really surprised when she uses the Jonah thing, so no real chance there. Natalia is a little too excited about Buck's death at first, I personally can't get past the cool comment, that feels insensitive but maybe that's just me, but either way she learned more about Buck and she left, so right now, she only exists through Buck and we know she's capable of leaving at any inconveniences (I don't really think finding out the guy you're trying to date is a sperm donor and is gonna end up housing the mother is just an inconvenience but you get me) so we will be heavily biased towards Buck on any future conflict because Buck is the only one we care about there and she left him before. Imma add Lucy here because it's also interesting the way that Lucy is the one that has the best fighting chances here, Buck and Luck could work and be a fun couple to watch, Lucy is a firefighter so it would be easy to make her exist outside of Buck and make the relationship balanced but the whole kissing Buck while he's drunk and dating someone else makes it so most people will be biased against it, the same cheating thing that makes us root for Karen and despise Eva, ends up working here, even if it's very mild version because we don't really like Taylor. And like, Shannon, she was always written to be fridged, it is very clear that Eddie was always planned to be a single dad army vet widower, so she never had a fighting chance to begin with, but she left Christopher, abandoned Eddie to deal with it all, so most people would never root for her anyway, because even Eddie is shown as not sure of her. I kinda think Ana falls into the same category as Ali, I don't think we see enough of her to care about her, but the panic attacks really kill her chances even if she didn't have something wrong about her introduction. And, well, Marisol has 3 seconds of screen time, there's not enough information to do anything there. Also, I think Lena falls in the same category as Lucy, it could work if they really wanted (I don't think they did) but Lena was the person that took Eddie to the first fight so she has points against her.

So the thing is, the show knows how to build relationships, so what the fuck are they doing with Buck and Eddie considering they are making sure they work together and individually if there isn't some sort of plan to eventually get them together?

#im just thinking yk#i had more to say but 5sos moved and now im in 5sos mode#you're getting this anyway#ill come back if do find out what else i wanted to say#911#thoughts thoughts thoughts

46 notes

·

View notes

Note

Speaking of Amy here's a really good thread on Reddit discussing it:

https://www.reddit.com/r/superstore/comments/mrhsia/would_amy_have_so_much_hate_if_she_was_a_man/

Amy is my favourite character because she's so real and true to herself. She's a human being, she makes mistakes and she always tries to fix it. All the hates she gets is just unnecessary.

I'm gonna quote some of the good ones:

"Amy gets more hate as opposed to the other, because they are exaggerated sitcom characters. When we see them express questionnable characteristics, we excuse it because we know it's unrealistic. But Amy is written more realistic, more relatable so we hold her accountable for her actions more than the other cartoonistic characters"

"I feel like her fear of dating Jonah is a legitimate thing to be cautious about, coming off of her marriage with Adam. Jonah and Amy meet while she's still married to Adam and trying to work on her marriage, so of course she won't be into Jonah from the start. She doesn't even separate or divorce until the end of season two.

But more importantly, Adam is a terrible partner, who is a nice guy. He always on and off has crappy jobs. Doesn't stick to any job. He is so unreliable as a life partner.

But then Jonah is similar UNTIL Amy. The last episode shows that in his interview. He consistently left jobs, changed careers, couldn't hold down any type of work experience. So, yeah, Amy should use caution when thinking about dating Jonah. She doesn't want a repeat of Adam.

And Adam wasn't a bad guy. Overall he is nice and he does care for both Emma and Amy (and eventually Parker). But he is a person who never grew up. So Amy has to carry their household. Jonah, in the beginning, is the same "privileged boy who never had to grow up". He got to wander for a different reason than Adam (due to his family's money), but he still represents the same person. A nice guy who doesn't have or take on responsibility."

"With Jonah her behavior towards him changes over time and can be a bit erratic giving the impression that she is toying with him. As a viewer you wish she would just feel the same love for him that he clearly has for her since the beginning since he is genuinely a good guy and easy to root for. But life is more complicated than that and it takes her a long time to figure things out. Eventually though she does and the journey those characters go on is a fun and interesting one."

In conclusion: Amy Sosa never did anything wrong in her life

oh jesus. the jonah/adam comparison. for the most part, we’re seeing jonah & amy’s story from jonah’s perspective, so to see him paralleled with The Ex is. ouch. but at the same time, it’s right. like no matter how much i love and identify with jonah and as much as i resent adam, as much as i WANT to say this comparison doesn’t hold up, the fact is that jonah easily could have fallen into the same cycle. adam’s string of abandoned hobbies, for example, feels like something that might happen to jonah. i adore the kid but if he didn’t put in the work to grow and set larger goals, he could very well have ended up putting amy in the same position as she started in.

obviously jonah and amy have something that amy and adam don’t, which is REAL chemistry. there’s real love there but at the end of the day, love in itself isn’t enough to sustain a long-term relationship. ESPECIALLY when there are kids involved. jonah takes huge steps to better himself, he actively involves himself in raising parker, he grows up because he’s seen what amy went through and he doesn’t want to do that to her again.

#jonah x amy#superstore#amy sosa#maxblumhartz#.txt#jonah IS easy to root for!! but just because we as an audience see that doesn’t mean amy should drop everything and run to him right away#i also wanna make a post about how she wasn’t wrong for 6.02 AND jonah wasn’t wrong for standing up to her when she came back#they’re both true! nuance!

34 notes

·

View notes

Link

Chapters: 6/20

Fandom: The Magnus Archives (Podcast)

Rating: Teen And Up Audiences

Warnings: No Archive Warnings Apply

Relationships: Martin Blackwood/Jonathan "Jon" Sims | The Archivist

Characters: Martin Blackwood, Jonathan "Jon" Sims | The Archivist, Tim Stoker (The Magnus Archives), Sasha James, Rosie Zampano, Oliver Banks, Original Elias Bouchard, Peter Lukas

Additional Tags: Post-Canon, Fix-It, Post-Canon Fix-It, Scars, Eventual Happy Ending, Fluff and Angst, I'll add characters and tags as they come up, Reference to injuries and blood, Character Death In Dream, Nudity (not sexual or graphic), Nightmares, Fighting

Summary: Following the events of MAG 200, Jon and Martin find themselves in a dimension very much like the one they came from--with second chances and more time.

Chapter Summary: Martin considers the repercussions of their argument, and he gets "his" stuff back from storage.

New chapter of my post-canon fix-it!

Read on AO3 above or read here.

Tumblr master post with all chapters is here.

***

The only word Martin could think of to describe the way he felt that morning was hangover. He woke up even earlier than usual and extricated himself from beneath Jon, who was entirely oblivious to the outside world. At least they had managed to communicate something, although it wasn’t the way he would have preferred to do it. At least they had made up, although he knew the actual fallout likely remained to be seen; arguments like that always seemed to twist their way back around.

Some of what Jon had told him was disturbing. He wished he knew what had come from Jon on that last day, and what had come from something that wasn’t Jon. Martin still couldn’t picture him willingly destroying the world. The idea that everything might have been different, that he might have been able to save Jon from that decision if he had just woken up that night, was hard to process. On the other hand, now that they were here, he had a new appreciation for Jon’s insistence on not letting the fears out. It was bad enough that they were responsible for the end of just two people in one dimension. The damage wasn’t just theoretical, and of course Jon had likely understood the possibilities in a way Martin couldn’t have before.

If he was being very, very honest, though, the thing that hurt the most was what Jon would have been willing to do to him. Before, it had felt like abandonment; Jon had been willing to leave him. It was that simple, and that selfish. It wasn’t that he didn’t rationally understand how it could be reasonable, or even an act of strength, if Jon really thought it was what he’d needed to do. It was that he himself could not have been that reasonable or strong about it. He didn’t believe he could have made a decision that would have led to them being apart, and like he’d told Jon—it had hurt that Jon could.

Now, though, he realized Jon had never seen it that way. Jon had sincerely believed that becoming the pupil of the Eye would not have changed him. He had believed he wasn’t sacrificing himself, that they could have still been together. He’d said that. Martin had almost forgotten, because he’d been trying so hard to tell Jon that Melanie and Georgie and Basira had been on their way to blow up the gas main, but now the words came back to him: We can be together, here. Until it’s over. And then—when that had failed—Jon had tried to send him away, but Martin understood now that even that hadn’t been a separation. Not for Jon, the way he was then. Jon would have kept Martin living in that world, whatever the cost, while he tortured himself driving it to its end.

Of course, it was also possible that the Eye had such a hold on Jon at that time that none of those thoughts had really been his—but if that was the case, there was no way Martin was going to allow him to do anything that would help him reconnect to it. He wouldn’t help Jon lose himself again. Whatever he wanted to do here, there had to be another way.

He had no idea how to approach any of this, and he certainly didn’t want to confront Jon with it when he woke up, so he decided to focus on something else instead—like his neck. It hurt. He supposed that made sense, given how he must have slept. After an unsuccessful attempt to stretch it out, he moved on to pick up the papers that were still on the floor. It hadn’t felt right to pick them up while Jon was gone; he’d wanted the reminder of why Jon wasn’t there, so maybe he wouldn’t let things get so heated the next time. He’d told himself he’d pick them up later, but then he’d fallen asleep and Jon had come home and it just hadn’t happened.

By the time he needed to wake Jon, Martin had decided that, for now, he was going to continue to do whatever Jon would allow to support his efforts. He didn’t imagine there was any chance Jon would slow down of his own accord, and at least that way he could make sure he was ok. The worst-case scenario would be if Jon started keeping secrets.

Jon was tired that morning. Martin could tell Jon had the same emotional hangover that he did, but it seemed like more than that. He occasionally stopped to stare distractedly into nothing. He took so long in the shower that Martin had to check on him twice, and ended up finding things to do in the bedroom until Jon was done. He was worried when Jon slipped his arm through his on their walk to work. That wasn’t a normal thing; Jon seemed to be relying on him to keep walking. Martin asked if he was ok, and Jon nodded absently in a way that wasn’t particularly comforting.

The fact was that he seemed to be getting worse, not better.

***

They were somehow only a little bit late, not that anyone was paying attention. Martin had to enter some updates in their online system, so he spent the morning at his desk. Tim was back from his investigation and Sasha was in her office, and despite his worries about Jon it was almost a nice morning with the four of them together. That concerned him; it meant he was getting too comfortable.

As he worked, checking records and following up on notes he’d made the previous week, he discovered another reason for concern. He realized for the first time that some memories of this world had blurred into others, his real memories, with no specific moment of revelation. He very clearly recalled several weeks spent tracking down some files that had been returned to the main library instead of the archives, and he didn’t realize until he was shaking his head over the enormous waste of time that it had only happened here.

Although it was an unimportant memory, it brought up a lot of questions. They still didn’t know exactly what had happened to the Jon and Martin from this world, and clearly they were connected somehow. What if Martin stopped being able to tell the difference between memories from the two worlds? Or worse, what if memories from this world were replacing memories of the one they came from? What if that was why it was so easy to feel occasional moments of contentment—because he was actually forgetting what had happened?

He automatically began to run through his memories, just to see, going backward from the moment they had arrived here. The tower, the panopticon, Annabelle Cane; his slowly expanding terror as Jon had grown more and more drawn to it all. The fear domains, all of them, but especially the corpse roots and the apartment fires and the domain that belonged to him—where people suffered without even the comfort that another living being knew or cared for their existence.

The cabin in Scotland, where everything had gone irretrievably wrong. How had it happened? He had left Jon alone, for one thing. Maybe he should have stayed, but he couldn’t have known. Jon had been trying not to know things, which should have been right. Avoid using evil powers. It still seemed like it should have been right. That was the worst part, wasn’t it? Every wrong decision looked like the right one. It had been so much worse for Jon, of course. If Peter Lukas had been able to see into him like Jonah Magnus could—if he had not pushed it just a bit too far—Martin could have very easily been the one to set off an apocalypse. Instead, he was thrown into the Lonely, unwittingly sealing Jon’s fate in the process. He wondered if he had—

An upsettingly familiar voice broke through his thoughts. Martin was so deeply distracted that at first, he thought he had manufactured it himself, out of his memories. When he looked up, though, he was met with the site of not only Peter Lukas, but also Elias Bouchard, and it took him a second to remember where he was. He started to stand up, but somehow had lost track of his physical surroundings, and managed to get tangled up in his chair. He ended up on the ground.

He could feel the entire room focus in on him, but he couldn’t look away from the two men in front of him. Peter was almost exactly as he remembered him, while Elias could not have been more different—it was hard to believe he was the same person. Of course, in most ways, he wasn’t. Peter chuckled uncomfortably while Martin continued to stare, and turned to the man standing next to him. “It seems we’ve disturbed your assistant.”

“Martin.” His name, spoken nearby, finally brought him out of his stupor. He looked up expecting to find Jon, but found Tim instead.

“Martin,” he said again, “are you all right?”

“Yeah.” He looked around. Sasha had come to the door of her office to see what was going on; Jon had gotten up too.

“I keep saying we need to replace that chair.” Tim laughed nervously and reached to help Martin to his feet. It felt like it took forever to stand up.

“Yeah. Yeah, that chair, it’s, um…” Martin’s words were swallowed up by silence as he turned his eyes to the floor.

“Looks like we’re ok here, then.” Elias clapped his hands and turned back to Peter. “Shall we continue?”

Peter took one last discomfiting look at Martin before they continued into Sasha’s office. She gave Martin a concerned glance as she ushered Elias and Peter in, and pursed her lips as he shook his head. She closed the door behind them.

“Martin, are you—” Jon started to ask.

“I’m fine.” He really was more embarrassed than anything, and set about righting his chair so he could retreat back into his data entry as quickly as possible. “I—I’m sorry.”

Jon started to say something else, but was interrupted as Elias came back into the room, setting Sasha’s door against the jamb. “Everything all right?”

“Yep.” Tim patted Martin on the back, just hard enough to startle him again. “Everything is perfectly fine.”

Elias nodded, looking curiously from Tim to Martin to Jon. “Well, in any case, I want to apologize. I meant to come by last week to see how the two of you were doing, but, well… as you all know, I hate this place and avoid being here whenever possible.” He spoke the last part under his breath and grinned, the sarcastic sort of grin that doesn’t reach the eyes. It was a look Martin could not recall ever seeing on Elias’s face before in his life, but somehow it fit. “Still, I should have checked in. I’ll catch up with you soon. And Martin—get a new chair? That’s embarrassing.”

And with that, he disappeared back into Sasha’s office.

“Well,” Tim said as he leaned back against Martin’s desk. “I’ve seen some reactions to Peter Lukas, but I think that is my new favorite.”

“Sorry.” Martin could feel how red his face was.

“Martin, are you—are you really ok?” He looked over to see intense concern on Jon’s face, and he knew Jon wasn’t asking about his fall.

“Yeah,” he replied, as reassuringly as he could. “I—I really am.”

Jon didn’t seem convinced, but Tim got Martin’s attention again. “Let’s get lunch. You need a break.”

“Oh, I—I would, but I brought mine today.” He gestured toward the paper sack on the corner of his desk. “I have to leave a bit early, so I thought I’d work through lunch.”

“Oh?”

“Yeah, I have to go pay some fees and pick up some stuff my old apartment building put in storage.”

“How are you getting there?”

“I was going to take the tube out,” Martin replied, realizing he hadn’t thought it through entirely. “I guess I hadn’t planned for getting back, but it’s just going to be some clothes and stuff for now… I can get a cab if it’s too much.”

“I’ll drive you,” Tim announced.

“Oh, no, thanks. I appreciate it, but—”

“It’s really not a problem.”

Martin considered; having a car really would be a lot more convenient. He didn’t know how much stuff was in storage, and he definitely didn’t know how it had been stored. Maybe it wasn’t even packed. “Are you sure you don’t mind?”

“Not at all. Besides, I want to talk with you.” Seeing the look on Martin’s face, he added, “No more questions. Mostly, I want to apologize properly for last week.”

“Well… yeah, ok. If you really don’t mind.”

“Nope. See you after lunch.” Tim headed for the door.

“Thanks,” Martin called after him.

As soon as Tim was gone, Martin turned back to Jon.

“You said you didn’t need help.” It was a statement, not an accusation, but Martin felt like he had to defend himself.

“I don’t! You heard him—he was really insistent. And he does have a car.”

“I can still go,” Jon said.

“It’s not a big thing.”

Jon bit his lip.

“Jon, you’re not feeling great, and I know how important it is to you to—to do your work. It’s fine.”

“You’re important, too.” Again, this was merely a statement, and again, it provoked too strong a reaction from Martin. This one, though, he tried to cover up.

“Yeah, well—I know that. You don’t have to prove it. And… if you’re not busy, or sleeping, you can help me put stuff away when I get home. Deal?”

Jon sighed, but agreed. “Deal,” he said, before turning back to his desk.

***

Martin ended up being very thankful for Tim’s help, and especially for his car. After they stopped by the rental office and he paid his fees, the storage lot was farther than he had imagined. Additionally, while most of his things were in bags, they were heavy contractor bags and there didn’t seem to be any logic as to what had gone where—if he’d come on his own, he would have had to spend a lot of time dumping things out and rearranging all of it to make it manageable. It would have been a pain, even if he had ended up calling a cab. As it was, though, Tim was able to help him with the heavier bags, and he didn’t have to sort everything out on the spot, so they finished with plenty of time.

“Let me get you a drink on the way back,” Tim offered, as he closed the boot on the final bag. “I still owe you an apology.”

“Tim, you just did me a huge favor. You don’t need to—”

“That was helping a friend. Apologies are measured in drinks.”

Martin considered. He did want to go. “Do you mind if I check on Jon?” he asked.

“Go right ahead,” Tim said. “I’ll wait in the car.”

Martin pulled out his phone, and thought about texting, but decided to call. Jon should be home, and that meant there was a good chance he was asleep. The phone did ring a bit long before he picked up.

“Everything all right?” Jon asked, and Martin thought he did sound like he may have just been roused from a nap.

“Yeah. I was actually just calling to ask you that.”

“Well, I’m home.”

“Good. Um… We got done a bit early, and Tim was asking if I wanted to grab a drink. Would you mind if I did?”

“Not at all.”

“Are you sure? Did you eat yet?” Martin asked. He kept his voice low so Tim wouldn’t overhear, although he didn’t exactly know why.

“Not yet.”

“I left one of those frozen meals on top in the freezer for you. Will you eat it?”

“Oh. Yes, of course. Thank you.”

Martin cringed at what he was about to say, but did it anyway. “Would you make it now?”

There was a pause. “Martin, are you serious?”

“Yes? I mean, you don’t have to, but I’d feel better if—”

“Fine.” Jon sighed, and Martin heard the sound of the freezer door opening a few moments later. “I’m doing it. Stop fretting and go have a drink.”

“Ok.” He was relieved. “Jon—thanks.”

“Go.” The call ended, and Martin couldn’t help but smile.

“OK, we’re good,” Martin told Tim as he climbed into the passenger seat. “Sure you won’t let me get it, though?”

“One hundred percent,” Tim answered. “How’s Jon?”

Martin debated whether he should give the polite answer or the real one, and went with something in between. “He’s… ok? To be honest, I’m a little worried about him.”

“Me too.” Tim started the car. “He wasn’t looking good last week when I was around.”

“Yeah?” Martin asked.

“He just seems tired,” Tim continued. “I mean, he’s always tired, ever since I’ve known him, but this is different. Tired and… distracted, I guess. Not like him.”

Martin nodded in agreement. “I’ve been trying to get him to take it easy, but—”

“He doesn’t care much for that, does he?”

“No. No, he does not.” Martin snorted, and Tim gave him a little grin as they headed out.

Soon they were sitting together at a table with a couple of beers in front of them.

“So,” Tim began, “I am officially apologizing for how I acted last week. I was a dick.”

Martin sighed. “No, you weren’t. You were worried, and Jon and I haven’t exactly been easy to—well, easy to anything.”

“Forgive me anyway?”

“If you insist,” Martin replied. “I forgive you, I guess.”

“Thanks. Cheers,” Tim said, holding up his glass. Martin obliged with a clink, and took a polite sip while Tim gulped down about half of what was in his glass.

“And for the record, I still don’t believe that you’re telling us everything, but—well, I imagine you have your reasons. I got to thinking over the weekend,” Tim said, after he had wiped his mouth off with his arm. “Sasha asked me not to say too much, but you know I was looking into some police records last week.”

Martin nodded. “Yeah, did something turn up?”

“Sasha was right. There was more. More than people had come to talk to us about.”

“For instance?”

Well… for instance, there was a kidnapping case about a month back. It turned out to be related to this cult that’s apparently been around forever, but never really done anything before. Not anything worth anyone’s time, anyway. I won’t get into details, I promised Sasha, but some of the officers thought they saw some things that… just shouldn’t have been possible. Not one or two officers, like a lot of them. And they lost some people.”

Martin wanted to ask questions, confirm his suspicions, but after what had happened with Oliver Banks, he didn’t want to push it again. “That’s horrible.”

“And here’s the real kicker.” Tim stopped to take another big drink. “There have been enough of these incidents that they’ve started asking the officers to sign a form saying they won’t talk about it. There’s been sort of an upset over it, actually. It’s all got lots of them pretty nervous, but no one is willing to make any outside statements, either. Not officially.”

Martin nodded again. This was really bad, but if it was happening, it was better that he know. He would tell Jon too, of course.

“Well, anyway, the point was I got to thinking—I know you and Jon disappeared around the same time all of this started. I’m not sure what to make of any of it, but whatever is going on… whatever you went through or feel like you went through, I understand why you might not want to talk about it.”

Martin knew he should say again that couldn’t remember, that he was sure it was nothing like that, it was probably completely unrelated—but he couldn’t. For one thing, it was a terrible lie. Everything Tim had witnessed—the way they had disappeared, the time they were gone, the way they had shown up again—it all fit together. For another thing, he knew he’d already said too much the last time they were out, and if he kept trying to lie he’d just look like an ass. Mostly, though, Martin hated lying to friends, and he couldn’t pretend anymore that this Tim didn’t feel like a friend.

So instead, he just nodded again, and took another sip of his beer.

“Well, if you need anything, I’m here.” Tim finished the remainder of his glass. “Speaking of which—where are we bringing your stuff?”

“Oh.” Martin realized he and Jon had never actually explained their living situation, and he felt the color rise into his face. “Jon’s flat?”

“I figured as much.” Tim leaned toward him. “So is that a long-term situation, or—?”

Martin didn’t know how to answer that, because he realized he didn’t know the answer. When they’d first gotten here, of course, they had just needed somewhere to go, and Jon had clearly wanted him there. Since then, he’d been so worried about Jon that he hadn’t questioned whether or not he should stay; it had just felt obvious that Jon needed him there. He had never actually asked him though, had he?

“I—I don’t know,” he stammered. “I guess we hadn’t talked about it.”

“Oh, god, relax,” Tim groaned. “If Jon didn’t want you there, you’d know. Subtlety is not his strength.”

“Sure.” Tim was basically right, of course. Still, they had been operating in survival mode for so long that maybe Jon hadn’t even realized not living together was an option. Mostly, though, it just wasn’t how people were supposed to move in together. They weren’t supposed to do it because they were scared.

Martin took a much longer sip of his beer, and was grateful when Tim changed the subject.

***

Miraculously, Jon was awake when they got back. He offered to help carry the bags upstairs from the car, but Tim and Martin both insisted he should let them take care of it, and he did seem relieved once he realized how heavy they were. Martin thanked Tim profusely for the help—it really would have taken a lot longer without him—and Tim said again he was happy to do it, and that he was looking forward to getting drinks with both of them sometime soon, when Jon was up for it.

“What did he mean, when I’m up for it?” Jon asked, after he was gone.

“Jon, everyone can tell you’re…” Martin considered what word to use. “Tired.”

“Is it really that bad?”

Martin wanted to ask Jon if that was a joke. Instead, he went with, “Yeah. It is.”

“I didn’t realize.” Jon was nervous. “Do you think Tim suspects anything?”

He decided not to mention that Tim very definitely did; it would only add stress, and that was not what Jon needed right now. He took a different route.

“Tim’s concerned, that’s all. You’re his friend and he’s worried.”

“Am I?”

“Yes. You are. I know there are a lot of complicating factors, and no, he’s not our Tim”—Martin stumbled a little over those words— “but in the simplest terms, he is Tim, and he is our friend.”

Jon sighed. “I’m not sure how friendly he would feel toward me if he knew what I’ve done.”

“What you—” Martin started to protest, but he reconsidered. He’d had enough arguing last night, and as obvious as his own responsibility for everything seemed to him, he doubted Jon would agree. “Never mind. How are you doing?”

“I’m all right,” Jon answered. “Good enough to help you sort through some of this.”

“Oh, Jon, I was just talking, you don’t have to—”

“I want to.” Then, with a slight smile, he added, “I certainly can’t let Tim take all the credit.”

“Right.” Martin shook his head, but also ended up smiling. “So, I’ll warn you—there’s not been a lot of organization. I maybe had to grab a little more than I actually intended.”

Ultimately, they dumped most of it onto the sitting room floor and began to sort everything into piles. Clothes Martin needed, things that could go to the office, some things they could use in the kitchen, stuff to go back to storage. As they sorted, Martin told Jon what he’d learned from Tim, which he suspected was related to the People’s Church of the Divine Host. He also told him about the police officers who had recently been sectioned. Jon nodded in concern while he spoke, but didn’t say much.

Before long, they had sorted out most of the obvious things. Martin was left going through a few boxes that had come along, containing mostly papers and legal documents and breakables and other things that couldn’t easily be thrown into bags.

“Want me to put some clothes away while you’re going through that?” Jon asked.

Martin cleared his throat. “Actually, it kind of came up when I was talking to Tim, and um—well, I realized we never talked about how long I would be staying here.”

“What do you mean, how long?” Jon seemed completely confused.

“Well, I kind of just… moved in. And we never talked about it.”

“What?” Jon asked again.

“You know, normally people talk about this. Moving in together.” Martin shifted uncomfortably in his spot on the floor.

“What did you want to talk about?” Jon asked.

“I mean, this is your place. I know I lost mine, or he lost his, or whatever, and this made sense when we got here, but—”

“Do you not want to be here?”

“What? No, I do, of course I do, but I just assumed it was what you wanted, too.”

“Because it is what I wanted.”

“I just hadn’t asked, that’s all.” Admittedly, Martin was relieved, but it still didn’t feel quite right. “I mean, we kind of had to be together before, and we have more time now to think about things, and I want this to really be a choice going forward because I do want to—well, I know I’m already on your nerves with the—”

“Stop. Listen to me,” Jon said. “I want you here. As long as you want to be here. I choose this.”

“Ok.” Martin stopped trying to explain himself, even though he wasn’t sure Jon really understood. He wasn’t trying to convince Jon he should move out, after all. He just wanted a sense of normalcy, to stop feeling like they were hurtling toward some inevitable doom. He didn’t want every moment to count; he wanted a future. He wasn’t sure how to put that into words, though.

“Can I help pay rent, at least?”

Jon got to his feet and grabbed a stack of shirts that were closest to him. “I really don’t care. At this point, money seems so… mundane.”

“Definitely in the shaving and eating category,” Martin agreed. “Still…”

“If it makes you comfortable, yes, of course.” Jon headed toward the bedroom, and Martin turned his attention back to the boxes in front of him.

He made it most of the way through with no trouble. Most of the things in the boxes could go back into storage; a few things, like his birth certificate, he would keep. And then he found a copy of his mother’s death certificate. He didn’t even have to look at the date to know; he remembered. It had happened here on the exact same day it had happened for him. Everything about it had been the same, actually. Not just when she passed, but all of it; everything about his relationship with her had been exactly the same. He didn’t understand why he felt so much disappointment.

“Martin?” Jon touched his shoulder. “What’s that?”

“Hm?” Martin glanced back and up at Jon.

“It’s just—you’ve been looking at it for five minutes. You haven’t moved.”

“Oh. It’s, um—well, look.” It was easier than saying it. He held it up until Jon recognized it.

“Ah.” Jon set down the clothes in his hand and sat down next to Martin.

“I guess—” Martin sighed. “I guess it was all just so—maybe I’d hoped that they had something to do with it, you know? But they didn’t. They weren’t here then. It was just how she was. And maybe it was how I was, too. Maybe I—”

“No.” Jon leaned against him, and gently rested his hand on the back of his shoulder. “You did nothing wrong.”

“Do you know what Elias showed me? Or Jonah, I guess? While you were—”

“I heard the tape, yes.”

“It was true, wasn’t it? She hated me.”

“She—she was ill, Martin. She loved you when she was well.” Martin nodded, and Jon leaned in even closer. “But just because she loved you doesn’t mean she was a good mother.”

“No. She wasn’t, actually.” Martin closed his eyes, and tried to just appreciate Jon’s presence, his warmth. “She was awful.”

Jon nodded.

“You know, I’ve never told anyone that.” Martin already felt ashamed. “Well, anyone except me.”

“Oh—right.” Jon knew what he meant.

“But it wasn’t her fault.”

“Does it matter if it was?”

“Yes. It does.” Martin tried to ignore the tear that squeezed its way out through his eyelids, because trying to stop them only ever seemed to bring more of them. “Jon—was the other part true too? Do I really look like my—like him?”

Jon hesitated, but eventually answered. “Yes. But that doesn’t mean you’re anything like him.”

“Do you know what he was like?”

“Yes. It was an accident, but I—” Jon paused. “I thought I needed to know what Elias could do, and, well… I couldn’t control it that well then. I saw more than I meant to. Is there anything you want to know?”

Martin felt another hot tear slide down his face, and tried to ignore that one too. “Am I like him?”

“No,” Jon said quietly. “Not at all.”

“Then I don’t need to know anything else.” A third tear fell, and a fourth, and he couldn’t ignore it anymore. He raised his arm to wipe his face, but Jon stopped him.

“Sorry. It’s been a long day,” Martin mumbled. “I’m—”

“No.” Jon turned Martin’s head toward him, and wiped his cheek with his thumb. “Don’t apologize.”

“Oh, come on. I’ve seen you cry once, and it was because—”

Jon kissed him.

“Jon—”

“Hush.” Jon crawled over Martin to straddle his lap, and kissed him again. Everything that had been swimming around in Martin’s head—their argument, Peter, his mother—it fell away, and all that was left was Jon. He let himself really breathe for the first time that day, resting his face against Jon’s shirt as they held each other.

“I love you,” Jon told him, when Martin looked at him.

“I love you too.” He turned his face up so Jon could kiss him again.

They stayed there until Jon’s hand gradually dropped from Martin’s face to his neck, and eventually down his arm, and Martin realized he was falling asleep.

“You awake?”

Jon didn’t answer him, and Martin didn’t particularly want to let go—so he picked him up, shifting Jon’s arms to his shoulders and then wrapping his own arms around Jon’s waist. He’d never done it before, but it was surprisingly easy; Jon was disturbingly light. Jon woke up enough to have a moment of panic when Martin stood up, and tightened his grip on Martin’s neck, but quickly relaxed and let himself be carried him to the bedroom.

“You all right?” Martin asked after he set him down on the bed.

“Mm.” Jon turned to lie on his side, and Martin brushed back the hair that had come loose.

“Jon, I’m really worried about you.”

“I’ll be ok,” Jon replied, catching Martin’s hand as he closed his eyes again. “I have you.”

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fade to Ash

Obviously, if I had done something like that, I'd be...

I've got nothing but memories right now. There was a time when I was absorbed by the deep sorrow and concern that I had blood on my hands for the choices I would soon have to make. Choices made to abandon someone I clearly wasn't sure would be up to waking up the next morning or some morning further down the line. That potent...ground shifting fear.

"You don't sound so stressed anymore..."

Only because it's no longer this eroding anxiety, but just a pit of well-groomed sorrow. Can't even ask what's happening in the middle of a pandemic; how my questions and concerns fill up every incinerator I've got. It's not that I want to treat it like this... it's just.

- [Ozarks Spoilers] -

Got through watching the recent season of the Ozarks, and the entire story of Ben got me real weak. It made me feel like I watching Of Mice and Men for a bit, but the sympathy grew ever more for a man who was just trying to make sense of a brutal reality. No...you don't actually want to exist on the cusp of the American Dream, you don't want to actually win when the cost is having to give up your humanity. Maturity suggests that absorbing these changes and consolidating "humanity" into bite sized snacks you throw at the dog you keep around is the only way to exist proper - when actually feeling, feeling anything at all, that much is a sin punishable by death. I won't push aside the note of his mental illness, but I don’t think it actually takes away from his argument. We got to see the decline of a human being, who...just didn’t belong there. For all the most emotive cogs in the grand machine they built - his intensity brought home the fact a few hard points. Whether you found hatred for his childish demeanor, or...honestly the guy was fucking charming. Smooth as fuck, weird as fuck, but didn’t give a damn about it and stood with principle. He belonged in the house of Snell. Say what you will of that woman, this season really made her into something...different. Her house was the den of the rejected. Not the iniquitous hovel of they that damn, but a home in the middle of burning world. The Langmore clan’s exodus here was something that didn’t stick out to me until the end, but the transition has been a fascinating one. You can’t help but trust the woman in this circumstance because for all of her wild card plays you begin to realize just how much she values principle. Principle is all the Langmore’s got except...for poor Ruth. Who, given the circumstances, Ruth is portrayed as “mature”, in her dealings with Byrde, and literally everyone else in this fucking world. At first you admire her tenacity, ingenuity...and then loyalty. But that loyalty nearly got her killed. It’s now that it becomes apparent that the Byrdes might not be the people you’re rooting for, no matter how much like Jonah’s character.

No, it’s...in this den of the principled few that I can’t help but admire. Ben...Ben got there too late. The first time he sets foot in there is his last, and he’s unsure of how to fix anything and the music played along these scenes gutted me. It was...it knew what you knew. From the start, his introduction, I was left wondering who would become the next fodder in the scene of character development - nearly as a joke, I teased the tropes but I didn’t immediately expect this one, though, to an extent, I always knew. Initially my thought is that it would’ve been about him gallantly taking out some douchebag’s life down with his own, considering his stark introduction at the school - even from then its clear just how principled he is. But what I got was...painful. I don’t always sit around to watch painful things, because usually they are presented as levels of cringe I don’t see worth in waiting around for, but this level of pain was something I couldn’t tear my eyes away from. Maybe it’s a personal thing, I can hardly know but for my skirting encounters with mental illness, I’m left adrift when it comes to Ben.

Ben died like a child. The music let you feel that...slowly growing into a melody that wouldn’t leave. Everytime you heard it, you knew what was going on, what was growing. It was methodic pacing; Ben didn’t belong anywhere. After the fact...you almost want to hear it again, but it never fully comes back, only in pieces, only in fading as if it was memory. It got too real, I mean...frankly I’ve never known what it’s been like to lose a loved one; but for all the simulations these dramas pose, this one...was really effective. I’ve never been one to latch onto character so quickly in fiction - sure this man or woman might be exceptionally badass, but as any writer dreams, the real chalice is getting a handful of the audience’s heart strings. Sure, several tropes can tug and pull and generic excuses for conflict may work as a standard bus, but then you’ve got to get specific. Ben’s illness, specifically, is not entirely a component of his character. I feel like it’s nearly asking me to believe that’s why he had to go, but cosnidering how it’s portrayal, and very possible mismatches with reality, I feel this misdiagnosis and key character point are not at all important. His interactions with Ruth define this, and for all his cool-headed light at the start of the season and throughout his decline, he doesn’t flip out against her. The show keeps repeating that he’s dangerous, to himself, and what is seen, others as well, but not to Ruth, not directly anyway. Maybe this isn’t grounds for determining his misdiagnosis, but it is grounds for consider the way his mental capacity is treated going forward. The pills stop him from feeling. As the audience we’re confused as to what should happen. His ability to experience life as most himself endangers everything, and honestly seems like poor judgment; obviously if you’re using something to get by and stay functional, by no means is it ideal to undo for a bit of feeling - but...

He’s given pills...not therapy.

I get it, there is a lot of his story that’s off screen, but the solution to Ben is not the pills. Ben just doesn’t belong. Granted, the pills would help Ben keep himself in check, but there is no indication that he wasn’t using those pills at the school? I guess that is the implication, but going into the Byrde house, it’s clear that he’s been taking them rather regularly. No...Ben’s solution was the Snell’s abode. It was Ruth - and the show makes you feel so close to that closure, then rips it away...slowly...and that’s why it hurts. You can’t just kill off one of the kids...no, they’re not kids anymore. But this guy? Yikes.

As if any of this is decent analysis of anything but frankly...it just...brings back memories. Many of them I don’t really want to think about. Ben didn’t belong in not just a world like the one the show presents, but...anywhere, here in the states. For the regard of central themes, that old hearty American principle is what makes you admire him and his new clan but...they don’t belong either. The mainstay of America prosperity is profit at any cost, and the Byrdes are pristine examples of that. Everyone is “protecting their family” but...that’s a lie. Too many ways out were presented, such that the entire season, I was waiting for the big reveal of him just bowing out to the feds but, they won, instead.

---

I looked at her and shuddered. Every day I peek over some platform to see...something, anything, I’m reassured that what she said about herself getting by just fine was more than true. While I am at ease, I sit down still very perturbed. Either she was lying to me for the longest time for the effect of that principle, something had changed while I was around, or it all was an unconscious attempt at keeping me still; whatever it might be, I hardly feel well about signing it off as such. It’s easier to just absorb the blame because that means I wasn’t suckered into something twice as toxic; it means that I was trying so fucking hard for a decent reason. It means that I failed, but I was not fooled. I’d much rather take that than assign villainy or that much confusion to someone I still admire, but can’t. It’s easy at a first glance to say that this “Ben” reminds me of her, but frankly...it feels more like a mirror. Being lied to or omitted at all angles for the perception of just not having it together enough to be trusted as an “Adult”. You can’t fix this Benjamin, go back to sleep; the music will fade soon enough, you’ll be fine.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Thoughts on Spiderman: Homecoming

I’ll put my short, non-spoiler version above the cut for people who haven’t seen it yet: it’s good. It’s really good, head and shoulders above the Amazing duology and it holds its own against the Raimi films more than you would think.

Specifically, it has two major strengths: first, as many people have noted, Tom Holland’s Spiderman feels like a real teenager way more than either Andrew Garfield or Tobey Macguire did - in part because the movie makes the most of out its science high school setting by giving Holland a secondary cast of other teens to bounce off of, and by making the conflict between his superhero life and his regular life being about high school things generally (making Lego Death Stars, Academic Decathalon meets, detention) instead of just about his romantic relationships.

Second, as other people have noted, Spiderman: Homecoming feels way more New York (more of a neighborhood Spiderman, you could say) than previous Spiderman movies. The Amazing movies’ idea of New York was some abstracted Times Square theme park, and with the best will in the world, even the Raimi films portrayed an extremely white New York that didn’t go beyond Midtown canyons and various landmarks. But Homecoming felt like Queens, from the multicultural student body at Midtown Science to Spiderman and the Prowler (you were great, Donald Glover!) arguing over which bodegas have the best sandwiches, to the jokes about how the outer boroughs aren’t well-stocked with tall buildings to web-swing off of, to Spiderman’s interactions with neighborhood locals who get pissed when would-be superheroes web their hands to their cars or repay subway directions with churros.

Protagonist

So let’s start with Tom Holland. For all that people complain about the Marvel “machine,” one of the things the machine does very well is make sure that their writers and directors nail the main characters, even if that’s at the expense of the plot, because you have to sell the audience on the character to get the audience to care, and because superhero plots are generally pretty secondary anyway. And Homecoming does a really good job of building on the excellent work that Civil War did. To quote myself:

“I buy Tom Holland more than I ever bought Andrew Garfield or Tobey Maguire - Tobey was always a bit too soft and saccharine for me to buy that he was the irreverent snarker behind the mask, whereas Andrew’s performance was way too much of an over-reaction to the backlash against Spiderman III, and came off as way too cool.

That’s the thing about Spiderman/Peter Parker that makes him tricky: he’s a nerd and a bit nebbishy (although he kind of ages out of that a little - there had to be something there that Mary Jane Watson liked), but once he puts the mask on, he gains the confidence to express himself, even if that is as a smart-alecky motor-mouth. There’s a side of Peter Parker that has an ego, a yearning to show the world that he’s not Puny Parker any more - after all, the first thing he did when he got super-powers was to get in front of TV cameras - that makes him prank J. Jonah Jameson to get back at him, or not just fight the Kingpin but relentlessly crack fat jokes at him.

As I’ve said above, it’s really easy to grab one part of that personality and not the other. And one of the things I really like about Tom Holland’s Spiderman is that I feel like you have both...”

So how did Homecoming build on this? First, the nerd side of Peter Parker was nicely contextualized by his high school (which because it’s an elite magnet school is full of nerds) - he’s extremely high-scoring (he’s bullied by Flash because Peter’s constantly showing him up in class, and he’s the lynchpin of the Decathalon team until MJ steps up in his absence) but you get the sense that he feels like he’s maybe too smart for school so he sometimes gets himself in detention and probably hurts his GPA a bit by not doing homework in favor of his own projects; he’s a joiner (Decathalon, band, etc.) because he’s not very socially confident (hence his small friend circle of Ned and MJ, hence his mini-freakouts about Liz’s party and the eponymous dance) BUT he’s also someone who over-extends himself and then quits (holy crap did that one hit close to home), so he’s seen as a bit of a flake.

Second, that nerd side nicely parallels his super-hero side, with the wonderful euphemism of the “Stark internship” (god, no wonder Flash is jealous). Peter is desperate for recognition, to get called up to the big leagues, to the point where he’s constantly biting off more than he can chew (literally taking the training wheels off too early) to prove himself to “Mr. Stark” and then tries desperately to hold everything together or explain his screwups away when it blows up in his face. (Notably, all of the major action setpieces in the movie except the last one involve situations where Peter’s over-enthusiasm has actually created a bigger problem: foiling the bank robbery causes the bodega fire, his investigation of the alien power source causes the damage to the Washington Monument, his web-slinging damages the fission gun that damages the ferry, etc.) At the same time, he’s trying to live up to the image of what he thinks a super-hero ought to be, whether that’s in posing for commuters and doing backflips for hot dog vendors or making quips at bad guys (notably, his smart-alecking always comes off as a mixture of nervous posing and too much energy rather than coming off as mean).

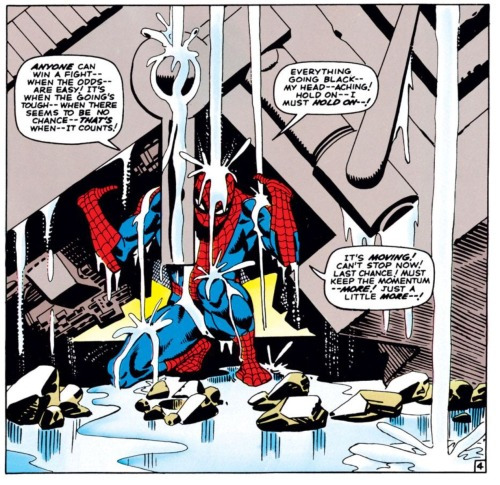

But most importantly, at root Spiderman is a genuinely selfless hero - his first thought is to save the bodega owner and the bodega cat, he gives the ferry rescue everything he’s got even if he comes up short as 98% sucessful, he tells criminals to shoot at him rather than at anyone else, and in the film’s master-stroke, he goes all-out to save Adrian Toombs who’s repeatedly tried to kill him the moment he realizes that his wing-suit has gone unstable, because Spiderman doesn’t want to “instant death” anyone. And he’s utterly determined, as we see in the whole third act where he goes right after Toombs despite getting his ass kicked by the Shocker, then pulls himself out from the rubble Toombs buried him under, then gets himself onto the Quinjet then saves Coney Island from the crashing Quinjet, and on and on....

Antagonist

So...Michael Keaton. While not given a ton of time, Keaton does a great job reframing Adrian Toombs as the voice of blue collar upper-middle-class resentment, justifying theft and murder with his hatred of Tony Stark and the 1% on the one hand and the need to provide for his family on the other, and selling you on how this guy gives more and more reign to his dark side while trying to hang on to his hypocritical moral code. Also, it was an inspired idea to build on the idea of the Vulture being a scavenger by making him both a salvage operator and someone who later makes his money by stealing the aftermath of the Avengers’ battles and turns them into weapons. (BTW, even though the wings were re-done as military high-tech, they still had some personality - the way they draped down feather-like when he was resting on the billboard, the way he used them to pick up Peter and maybe use them as blades.)

Critically, the movie didn’t kill him off. See, Marvel’s villain problem isn’t always about how generic they are (although that was a problem for Malekith and Ronan the Accuser) but that they constantly kill off their villains which means that there’s no opportunity to build up a relationship between hero and villain - Robert Redford’s HYDRA true believer or Ultron would be great recurring villains, except they’re dead now. If Keaton ever wants to reprise his role, it would only take a jailbreak to put him back in the mix gunning for revenge according to his own code.

Also, the movie did a good job seeding future villains. We see the mantle (or rather the gage) of the Shocker get passed on in the film, the Tinkerer seems to get away in the end so is on hand for future movies, we get a great setup for why the Scorpion would go after Spiderman, and we even meet the Prowler who’d make for a great frenemy villain.

Secondary Cast

The kids are more than all right, they’re damn fantastic. Ned was a great audience stand-in as well as a voice of reason, was great as “the chair,” and even got to use the webshooters, Liz Allen nicely avoided a lot of “superhero girlfriend” pitfalls, Flash was a nice alternative to the over-used jock archetype, and Zendaya was a genuinely oddball presence who makes for a very different MJ than we’ve ever seen before (my friend @elanabrooklyn thinks that she’s basically comics Jessica Jones in all but name, which I would be ok with).

Marissa Tomei as Aunt May could have used more screen-time, but what there was, was great, from the ongoing gag that she’s completely oblivious to the fact that pretty much all the men in the service sector she meets are in lorb with her, to her very real mix of showing concern and trying to encourage while giving a teenager room, to her final F-bomb - which thankfully cut short the “Aunt May can’t know” storyline.

RDJ as Tony Stark actually didn’t over-shadow the film as much as people had worried - mostly, he’s there being simultaneously neglectful (answering some text messages, providing some encouragement outside of post-crisis situations, and actually explaining why you’re doing what you’re doing would be a good idea, Tony) and over-bearing (tracking devices and surveillance cameras are not a substitute for communicating, Tony), which is sort of how you’d expect him to handle being a mentor/surrogate father on his first go-round.

Plot

Despite how confident people were about what was going to happen in the movie from the trailers, the film actually did a great job throwing the unexpected at you, whether it’s the suburban lawn-chase sequence that wasn’t in the trailers, or the FBI showing up on the ferry, or the fact that Peter and Ned were directly responsible for the Washington Monument crisis, or why the Vulture and Spiderman were on a plane.

More importantly, the high school plot really really worked and intersected nicely with the superhero plot - Peter’s indecision about using his Spiderman persona to boost his and Ned’s social standing leading into the suburban lawn-chase, the Academic Decathalon giving the Washington Monument rescue real stakes, and best of all, the moment where Adrian Toombs opens the door for his daughter’s date and the commonplace dad/boyfriend tension goes into overdrive.

313 notes

·

View notes

Text

I saw the future unfold (in silver and gold)

by Clubsheartsspades

Watching over his new world takes a lot more out of Jonah than he thought it would. His eyes hurt - all of them at once - it becomes harder and harder to See, his questions hold no power anymore. It is, of course, because the world changes, Jonah just has to get back to his roots, find statements, stories, human fear to hold himself and his powers together. It's that easy, it has always been that easy.

Somewhere, not that far away actually, Jon can't stop Knowing. Maybe because he doesn't try to resist anymore.

Words: 4075, Chapters: 2/2, Language: English

Fandoms: The Magnus Archives (Podcast)

Rating: General Audiences

Warnings: Creator Chose Not To Use Archive Warnings

Categories: Gen

Characters: Jonathan Sims, Martin Blackwood, Jonah Magnus, Elias Bouchard

Relationships: Martin Blackwood/Jonathan Sims

Additional Tags: I'm getting this out before s5 has a chance to ruin it, but it's just Jonah trying out his powers over the apocalypse and failing, Jon is trying to have an okay day and the Eye lets him, the Eye isn't actually that bad, Martin makes tea but it's not tea until it is, because I suck at writing serious stuff, too many metaphors in like the second half of this, actually no too many metaphors in general because that's just my writing style, not beta read we die like Tim

source https://archiveofourown.org/works/23422333

0 notes

Link

Maniac, a new, darkly comic Netflix miniseries starring Emma Stone and Jonah Hill, is the rare project that I like both more and less the longer I think about it.

By the time it reaches the midpoint of its 10 episodes, the series is one of the more confident and assured examples of what I call “Big Moment TV,” where every episode involves some jaw-dropping visual or conceit that’s meant to send you to Twitter to buzz, “Did you see that?!”

And as directed by Cary Joji Fukunaga, the genius (and newly minted James Bond director) behind everything from the wonderful 2011 Jane Eyre to the visuals of the first season of True Detective, those moments really land. I wanted to go to Twitter to talk about them, except that would have been a violation of my screener agreement with Netflix.

And yet there’s something so calculated about Maniac. There’s rarely the thrill of the unexpected, which is tough to explain in a series that longs, deeply, to provide the thrill of the unexpected. Every time the story would shift, or enter another genre entirely, or let the actors play other characters than the ones they came in as, I would nod and say, “Sure. Makes sense!” Which is not what I think anybody involved was going for.

Some of that stems from performance (Hill is a fine dramatic actor but maybe not the guy you want sublimating all of his live-wire energy to play a depressive), and some of it stems from the storytelling, which is a wackadoodle pastiche of “mind-fuck cinema,” in which the movies ask you to question reality and wonder what’s going on and so on.

But not only have you seen the basic dramatic beats of Maniac over and over again, but Maniac takes great pains to explain to you, at every turn, what’s going on, how the characters feel and think about it, and what those crazy, trippy visuals could mean. It’s a mind-fuck movie so unconfident in its ability to fuck with you that it follows up every big reveal or jaw-dropping mindscape with a moment that seems to ask, “Did you see what I did there?”

This probably already sounds like a bunch of ideas thrown together in haste, which don’t really cohere. It is, and it isn’t, and to explain why, I’m going to have to spoil the show almost in its entirety, so follow me after the massive spoiler warning to talk about why it’s easy to remain interested in Maniac but hard to become truly invested in it.

The rise of Big Moment TV has been driven by two factors. The first is that TV storytelling has grown more complex in terms of serialization, but the second is that lots of people still kind of half pay attention to what they’re watching, because they’re doing chores or playing a game on their phone or whatever. So if you watch an episode of Game of Thrones and there’s a big, bloody death or something, that jars you out of whatever other thing you’re doing and forces you to pay attention.

But, increasingly, these sorts of shows feel driven less by the whims of their characters than by the whims of their creators. Game of Thrones went from a show that made you feel the weight of every death to a show that wantonly killed characters without much regard to emotional resonance or storytelling sense. And that’s, ultimately, part of the fun of that show, but it took it from a must-watch to a fun show that often struggles to reach its potential.

But Big Moment TV has increasingly evolved to a point where it’s less about a big death or a big plot twist and more about anything unusual that will get you talking on Twitter, as I explored in this article about The Magicians and Legion. And those two shows form useful comparison points for Maniac, with its occasionally fascinating, occasionally awkward attempts to fuse Big Moment TV, over-explanatory mind-fuck pastiche, and what amounts to falling asleep in front of Netflix. (It was an early adopter of Big Moment TV, lest we forget House of Cards’ entire storytelling ethos.) All while the algorithm randomly shuffles through things it thinks you might like.

(And really do turn away at this point if you want to remain unspoiled about this series, because knowing the premise of this show could potentially ruin it.)

The story focuses on Annie (Stone) and Owen (Hill), two 20-somethings struggling with barely repressed trauma and other mental conditions in a near-future New York where everything, including friendship, has become a part of the gig economy. You can even sell your likeness for various ads and stock photos, as Annie has done, which means that when Owen bumps into her at a purported pharma trial for a new drug, he both feels he already knows her and fears he’s hallucinating her. (He was diagnosed with schizophrenia, see.)

In one episode, Owen and Annie become stuck in some sort of espionage thriller. Netflix

Anyway, the drug trial turns out to be a complicated procedure designed to put people through a sort of psychological boot camp, where in stage one they relive their greatest trauma (the loss of her sister for Annie; a suicide attempt — that might not have even happened — for Owen), attempt to better understand the roots of their psychological issues in stage two, and then confront those issues and their trauma in stage three, in hopes of healing and moving on.

The trial is overseen by a group of people cosplaying as the characters erasing Jim Carrey’s memories in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, including Justin Theroux, the dryly funny Sonoya Mizuno, and (I swear I am not kidding about this) Sally Field playing a depressed computer.

The bulk of the series involves what happens when a mechanical malfunction results in the fusing of Owen and Annie’s subconsciouses, which results in them essentially entering an anthology series. Across five of the season’s 10 episodes, they play different characters, in different genres, following what amounts to Fukunaga’s syllabus for a “history of American indie film” class. There are suburban capers, and an extended (kinda awful) journey through a gangster/crime movie tale, and a story where Owen becomes a hawk. (That last one’s a lot of fun!)

This is, I think, a pretty compelling way to explore two characters who seem paper-thin at first. By having Annie and Owen journey through both of their subconsciouses at once, the show could theoretically fill in details about these people’s core beings while still allowing for plenty of action and adventure. Seeing Annie as a Long Island housewife trying to steal a lemur, or as a con artist interrupting a seance, or as a half-elven ranger in a generic fantasy kingdom gives us different sides of the actual Annie’s persona and lets Stone have a lot of fun.

But I could never escape the feeling that the show’s weirdness was less an organic investigation of two people in crisis and more a mechanism designed to keep me watching. The journeys that Annie and Owen take through their brains feel assembled more from other movies and TV shows than from genuine psychological exploration.

On a show limited only by the human imagination (at least in theory), these adventures stay frustratingly earthbound. They’re “imaginative,” in the manner of a college student who’s carefully cultivated her persona out of bits and pieces of other personas she’s seen elsewhere, rather than authentic.

The strange facility where Owen and Annie bond is a weird setting unto itself. Netflix

It feels a little churlish to complain about this, because watching Maniac is a lot of fun. I sat down intending to watch a couple of episodes one day and ended up watching seven, because I really did want to see what would happen next. The writing staff — led by Patrick Somerville of The Leftovers fame — has given real thought to the story of all 10 episodes as well as the story of each episode, which leads to fun journeys through the various genre pastiches the writers come up with. (I loved the Long Island-set crime caper, which felt straight out of a Coen brothers movie.)

But I could never get past the stage where I was enjoying the show’s considerably gorgeous surfaces to access some deeper level. And then after watching the finale, I read a quote from Fukunaga in a recent GQ profile of him, and something clicked. He said:

Because Netflix is a data company, they know exactly how their viewers watch things. So they can look at something you’re writing and say, We know based on our data that if you do this, we will lose this many viewers. So it’s a different kind of note-giving. It’s not like, Let’s discuss this and maybe I’m gonna win. The algorithm’s argument is gonna win at the end of the day. So the question is do we want to make a creative decision at the risk of losing people. …

There was one episode we wrote that was just layer upon layer peeled back, and then reversed again. Which was a lot of fun to write and think of executing, but, like, halfway through the season, we’re just losing a bunch of people on that kind of binging momentum. That’s probably not a good move, you know? So it’s a decision that was made 100 percent based on audience participation.

Now, listen, the notes-giving process in Hollywood is important. I’m not somebody who rails against notes, or thinks they ruin the creative process or tear down impeccable works of art. But something about letting a computer give those notes speaks to why Maniac, ultimately, felt less human than human to me, why it always seemed like it was assembled more than it was a deeply felt passion project for anyone. And, indeed, the series is based on a Norwegian show of the same name, and the various genre pastiches look a lot like other Netflix shows if you squint, and every single actor feels specifically chosen to appeal to a very specific demographic.

This would almost feel like Netflix snarkily commenting on itself if the show didn’t take itself so seriously. The fact that it turns into a genuinely sincere story of how Owen and Annie come together to better each other’s lives in the last few episodes is either the bold swing that saves the enterprise or a case of too little, too late. I’m more in the former camp than the latter, but it’s not hard for me to imagine talking myself out of that stance.

And yet there’s something kind of beautiful about a series that applies the dull plotting of most other TV shows — all life-and-death stakes and, “We’ve gotta get to the [plot device] before they do!” numbness — to two emotionally damaged people trying to heal. There’s a bravado here that I can’t write off, even if I never felt like the show went deep enough to turn either Owen or Annie into anything more than ciphers, despite all of the self-analyzing monologues both deliver in an attempt to sell their complexities.

Whatever complaints I have about the show, then, might be a part of its commentary on a world where our mental horizons are so often occupied by stories we’ve heard elsewhere. If you and I somehow had our subconsciousnesses fused, and then went through a series of adventures in dreamspace together, wouldn’t it be more likely that those adventures would be drawn from the movies and TV shows we had watched than something wildly original?

Maniac isn’t weird enough to really achieve what it wants to, but it does say something — however accidentally — about how reality is already weird enough. Maybe that’s why we’re so content to live inside the dreams of others.

Maniac is streaming on Netflix.

Original Source -> Netflix’s Maniac, with Jonah Hill and Emma Stone, is either too weird or not weird enough

via The Conservative Brief

0 notes

Photo

New Post has been published on https://shovelnews.com/netflixs-maniac-with-jonah-hill-and-emma-stone-is-either-too-weird-or-not-weird-enough/

Netflix's Maniac, with Jonah Hill and Emma Stone, is either too weird or not weird enough

Maniac, a new, darkly comic Netflix miniseries starring Emma Stone and Jonah Hill, is the rare project that I like both more and less the longer I think about it.

By the time it reaches the midpoint of its 10 episodes, the series is one of the more confident and assured examples of what I call “Big Moment TV,” where every episode involves some jaw-dropping visual or conceit that’s meant to send you to Twitter to buzz, “Did you see that?!”

And as directed by Cary Joji Fukunaga, the genius (and newly minted James Bond director) behind everything from the wonderful 2011 Jane Eyre to the visuals of the first season of True Detective, those moments really land. I wanted to go to Twitter to talk about them, except that would have been a violation of my screener agreement with Netflix.

And yet there’s something so calculated about Maniac. There’s rarely the thrill of the unexpected, which is tough to explain in a series that longs, deeply, to provide the thrill of the unexpected. Every time the story would shift, or enter another genre entirely, or let the actors play other characters than the ones they came in as, I would nod and say, “Sure. Makes sense!” Which is not what I think anybody involved was going for.

Some of that stems from performance (Hill is a fine dramatic actor but maybe not the guy you want sublimating all of his live-wire energy to play a depressive), and some of it stems from the storytelling, which is a wackadoodle pastiche of “mind-fuck cinema,” in which the movies ask you to question reality and wonder what’s going on and so on.

But not only have you seen the basic dramatic beats of Maniac over and over again, but Maniac takes great pains to explain to you, at every turn, what’s going on, how the characters feel and think about it, and what those crazy, trippy visuals could mean. It’s a mind-fuck movie so unconfident in its ability to fuck with you that it follows up every big reveal or jaw-dropping mindscape with a moment that seems to ask, “Did you see what I did there?”

This probably already sounds like a bunch of ideas thrown together in haste, which don’t really cohere. It is, and it isn’t, and to explain why, I’m going to have to spoil the show almost in its entirety, so follow me after the massive spoiler warning to talk about why it’s easy to remain interested in Maniac but hard to become truly invested in it.

The rise of Big Moment TV has been driven by two factors. The first is that TV storytelling has grown more complex in terms of serialization, but the second is that lots of people still kind of half pay attention to what they’re watching, because they’re doing chores or playing a game on their phone or whatever. So if you watch an episode of Game of Thrones and there’s a big, bloody death or something, that jars you out of whatever other thing you’re doing and forces you to pay attention.

But, increasingly, these sorts of shows feel driven less by the whims of their characters than by the whims of their creators. Game of Thrones went from a show that made you feel the weight of every death to a show that wantonly killed characters without much regard to emotional resonance or storytelling sense. And that’s, ultimately, part of the fun of that show, but it took it from a must-watch to a fun show that often struggles to reach its potential.

But Big Moment TV has increasingly evolved to a point where it’s less about a big death or a big plot twist and more about anything unusual that will get you talking on Twitter, as I explored in this article about The Magicians and Legion. And those two shows form useful comparison points for Maniac, with its occasionally fascinating, occasionally awkward attempts to fuse Big Moment TV, over-explanatory mind-fuck pastiche, and what amounts to falling asleep in front of Netflix — an early adopter of Big Moment TV, lest we forget House of Cards’ entire storytelling ethos — while the algorithm randomly shuffles through things it thinks you might like.

(And really do turn away at this point if you want to remain unspoiled about this series, because knowing the premise of this show could potentially ruin it.)

The story focuses on Annie (Stone) and Owen (Hill), two 20-somethings struggling with barely repressed trauma and other mental conditions in a near-future New York where everything, including friendship, has become a part of the gig economy. You can even sell your likeness for various ads and stock photos, as Annie has done, which means that when Owen bumps into her at a purported pharma trial for a new drug, he both feels he already knows her and fears he’s hallucinating her. (He was diagnosed with schizophrenia, see.)

In one episode, Owen and Annie become stuck in some sort of espionage thriller. Netflix

Anyway, the drug trial turns out to be a complicated procedure designed to put people through a sort of psychological boot camp, where in stage one they relive their greatest trauma (the loss of her sister for Annie; a suicide attempt — that might not have even happened — for Owen), attempt to better understand the roots of their psychological issues in stage two, and then confront those issues and their trauma in stage three, in hopes of healing and moving on.

The trial is overseen by a group of people cosplaying as the characters erasing Jim Carrey’s memories in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, including Justin Theroux, the dryly funny Sonoya Mizuno, and (I swear I am not kidding about this) Sally Field playing a depressed computer.

The bulk of the series involves what happens when a mechanical malfunction results in the fusing of Owen and Annie’s subconsciouses, which results in them essentially entering an anthology series. Across five of the season’s 10 episodes, they play different characters, in different genres, following what amounts to Fukunaga’s syllabus for a “history of American indie film” class. There are suburban capers, and an extended (kinda awful) journey through a gangster/crime movie tale, and a story where Owen becomes a hawk. (That last one’s a lot of fun!)

This is, I think, a pretty compelling way to explore two characters who seem paper-thin at first. By having Annie and Owen journey through both of their subconsciouses at once, the show could theoretically fill in details about these people’s core beings while still allowing for plenty of action and adventure. Seeing Annie as a Long Island housewife trying to steal a lemur, or as a con artist interrupting a seance, or as a half-elven ranger in a generic fantasy kingdom gives us different sides of the actual Annie’s persona and lets Stone have a lot of fun.

But I could never escape the feeling that the show’s weirdness was less an organic investigation of two people in crisis and more a mechanism designed to keep me watching. The journeys that Annie and Owen take through their brains feel assembled more from other movies and TV shows than from genuine psychological exploration.