#john von neumann

Text

“En mathématiques, on ne comprend pas les choses, on s’y habitue.” 🔢

John von Neumann

Gif Giphy

#gif animé#giphy#école#chats#funny cats#mathématiques#classe#cartoon#quotes#john von neumann#humour#funny pics#fidjie fidjie

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Institute for Advanced Study (IAS) computer project team, Princeton. 1952.

#vintage#research#mid-century#University#mathematics#stored-program computer#Fuld Hall#John von Neumann#string theory#midcentury#history#academics#center#1950s#mid century

170 notes

·

View notes

Photo

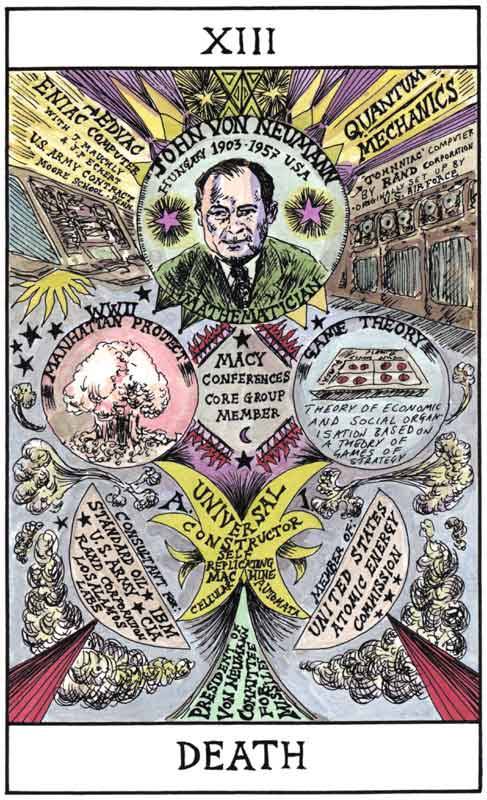

Death. Art by Suzanne Treister, from HEXEN 2.0.

John von Neumann

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reading the introduction to von Neumann's Games and Economic Behavior. He's very in touch with the poverty of the state of economics, the huge challenges involved, and the need to focus on making a difference where differences can be made.

His portrait of how physics and mathematics coevolved is crisp and beautifully motivates how difficult applying the mathematical tools of the day to social problems is. I think he's after something like the Asimovian dream of psychohistory—of actually being able to predict human behavior on generational timescales and engineer societies based on those predictions. That same dream has drawn cybernetics nerds into econ for generations.¹

One thing that stands out: he smacks down so many criticisms of microeconomics still bandied around today. He does it very well, moving fluidly from one point to another, always hemming the opposition in. I'm happy, because he puts these arguments in such wonderful context. I'm sad, because people still make them now and don't seem to overcome his responses when they do so.

"Why does econ focus on these toy problems?" Because they're tractable and let us compare theory with both observation and intuition, which is unskippable foundation-laying (compare probability theory, which was first used to characterize obvious problems before we got things like Buffon's needle).

"Why doesn't sprinkling math on economics work?" Well, applying calculus works when doing marginal analysis, but most of the time, we mostly don't know what's happening. There's often no setup—no ansatz—we can do to gain new insight. When economists do this, they're often just putting fancy mathematical clothes on their verbal arguments, not discovering anything new. And calculus itself emerged from the need to solve kinematics problems in physics, and the kinds of problems we want to understand in economics often seem pretty different from this. Von Neumann really hopes that we'll discover new kinds of math to better understand economics, and Games is meant as a step in that direction.

"Why bother with math at all? Trying to reduce humans to a bunch of numbers is foolish!" Well, we can observe humans exhibiting preferences and making choices, which immediately suggests there's quantitative data (ordinal utilities) we can work with. And studying the impact of ordinal utilities at the margin using calculus is no more problematic, von Neumann argues, than studying clumps of atoms and other indivisible quanta as continuous bodies.

"Why don't we try to understand more important and complicated systems, like the US economy?" Because the system is complex and the data is pitifully sparse for that complexity²—and there's nothing to be gleamed from very complex data that we cannot theorize about. "Observation is theory-laden" isn't language von Neumann had, but he seems to be reaching for this idea. Von Neumann even does a David Deutsch-esque maneuver of saying, "we scanned the heavens for millennia in vain before it gave us ideas, which made all the difference."

---

1. The boldest form of this vision has a serious problem, which Karl Popper elucidated: as long as new knowledge is being created, and as long as predicting human behavior depends on understanding the state of human knowledge, prediction will always be limited, because the discovery of new knowledge is unforeseeable by definition.

2. I think a dynamicist breaking this point down further would talk about things like the number of parameters (and the enormous phase space that the economy must live in), the lack of stationarity on the timescales we can look at, and how few of the driving processes can be observed. As of 2023, my understanding is that most macroeconomic models taken seriously need to capture both behaviors we know must happen (like capital costs reflecting technology efficiencies) and strongly suspect must happen (like hysteresis in labor markets leading to sustained unemployment). Just capturing those behaviors makes the models so capacious that falsifying them, never mind fitting them to reality, seems hopeless. What's amazing is that von Neumann must have known much less about these things when he was writing, but he understands this phenomenon of data poverty extremely well.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

#John von Neumann#computer#technology#mathematics#genius#photography#black and white#vintage#men's fashion

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reflections on the Paradox of Existence

Confessions of the twisted endeavors of youth's uncorrupted innocence, All becomest heresy, malediction and entropic discordance. The further we are from conception the larger our faults become.

It takes a sick atheist to reject all the entropy that comes with prosperity, it takes god to create a devil for us to realize we are not meant to be as we are.

We are a convoy of death spirals waiting to meet our final maker, we find the god in every demise and hope in every devil.

No fictive result of ours is the result of our suffering, rather our dependent relations converge us to bound incarceration.

This piece is meant to make you think about your ambitions, goals and dreams.

You can't escape the irony of your making, be careful what you wish for.

You'll need more than love, happiness and honesty to simply survive let alone thrive, let's make that a reality.

The image of the person is John von Neumann

Directly from the wiki article:

John von Neumann (/vɒn ˈnɔɪmən/ von NOY-mən; Hungarian: Neumann János Lajos [ˈnɒjmɒn ˈjaːnoʃ ˈlɒjoʃ]; December 28, 1903 – February 8, 1957) was a Hungarian-American mathematician, physicist, computer scientist, engineer and polymath. He had perhaps the widest coverage of any mathematician of his time,[9] integrating pure and applied sciences and making major contributions to many fields, including mathematics, physics, economics, computing, and statistics. He was a pioneer of the application of operator theory to quantum mechanics in the development of functional analysis, the development of game theory and the concepts of cellular automata, the universal constructor and the digital computer. His analysis of the structure of self-replication preceded the discovery of the structure of DNA.

During World War II, von Neumann worked on the Manhattan Project on nuclear physics involved in thermonuclear reactions and the hydrogen bomb. He developed the mathematical models behind the explosive lenses used in the implosion-type nuclear weapon.[10] Before and after the war, he consulted for many organizations including the Office of Scientific Research and Development, the Army's Ballistic Research Laboratory, the Armed Forces Special Weapons Project and the Oak Ridge National Laboratory.[11] At the peak of his influence in the 1950s, he chaired a number of Defense Department committees including the Strategic Missile Evaluation Committee and the ICBM Scientific Advisory Committee. He was also a member of the influential Atomic Energy Commission in charge of all atomic energy development in the country. He played a key role alongside Bernard Schriever and Trevor Gardner in the design and development of the United States' first ICBM programs.[12] At that time he was considered the nation's foremost expert on nuclear weaponry and the leading defense scientist at the Pentagon. He designed and promoted the policy of mutually assured destruction to limit the arms race.[13]

Von Neumann's contributions and intellectual ability drew praise from colleagues in physics, mathematics, and beyond. Accolades he received range from the Medal of Freedom to a crater on the Moon named in his honor.

#John von Neumann#Quantum Physics#Philosophy#Nihilism#Existentialism#Optimism#Pessismism#Reflection on the paradox of existence#Nuclear Science#Atomic bomb#World war 2#Religion#Atheism#Perspective#Criticism#Responsibility#History#Tradition#Mathematics#Prison complex#Irony#Thought provoking

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

When you’re really into math.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Despite all the language professing otherwise, in general the education system of the United States is based entirely on genetic determinism.

A child is born assumed to have innate traits, including, for example, a preference as to what they want to be when they grow up (somehow just waiting fully-formed inside of their six-year-old selves).

Then they are thrown into the school system, a competitive academic meritocracy wrapped in an obtuse hierarchical bureaucracy, a structure in which they will spend most of their young adult life, forced to learn mostly from their peers, who know as little as they do.

Those who can’t sit through it are given drugs until they can.”

#education#philosophy#society#culture#anthropology#school#university#history#genius#erik hoel#albert einstein#john von neumann#richard feynman#aristocracy#tutoring#learning#purpose#economics

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Quantum Foundations: The Galactic Center File

Many astrologers have noticed the prominence of Saturn (dedication, discipline, determination, creations of enduring value etc.) and Jupiter (luck, blessings, inspiration, search for deep meaning and reliable knowledge etc.) in the natal charts of many scientists. The following statements depend on the accuracy of the birth-data, so if the publicly available birth-data is correct or even approximately correct then the following astrological facts are true (or approximately true). First, note, Isaac Newton: Saturn 19 deg Pisces 53 min conjunct Jupiter 14 deg Pisces 08 min and Werner Heisenberg: Saturn 14 deg Capricorn 43 min conjunct Jupiter 15 deg Capricorn 28 min, this is well known to astrologers and the significance of these placements is relatively straightforward. The prominence of the Galactic Center, however, is relatively less well known and that is one of the reasons I’m including the Galactic Center (GC) in ‘AveryCanadianFilm’. The following astrological aspects, for deceased physicists, are from publicly available birth-data.

Newton: Mercury 20 deg Sag 56 min conjunct GC 21 deg Sag 52 min.

Einstein: Sun 23 deg Pisces 30 min square GC 25 deg Sag 10 min.

Heisenberg: ASC 21 deg Gemini 07 min opposes GC 25 deg Sag 29 min.

Pauli: [Venus 20 deg Gemini 18 min conjunct Neptune 24 deg Gemini 55 min]

opposes [Chiron_R 24 deg Sag 39 min conjunct GC 25 deg Sag 28 min].

Max Born: Jupiter_R 27 deg Gemini 20 min opposes [Moon 24 deg Sag 25 min conjunct GC 25 deg Sag 13 min].

von Neumann: Uranus 26 deg Sag 23 min conjunct GC 25 deg Sag 30 min.

Schrödinger: Chiron 29 deg Gemini 56 min opposes GC 25 deg Sag 17 min.

de Broglie: Grand Trine in fire involving Jupiter-Chiron-GC

Jupiter_R 24 deg Aries 56 min trine Chiron 22 deg Leo 50 min trine GC 25 deg Sag 21 min.

David Bohm: Sun 28 deg Sag 01 min conjunct GC 25 deg Sag 42 min.

The following astrological aspects, for physicists still living at the time this was posted, are from publicly available birth-data .

Anthony Leggett: Chiron 25 deg Gemini 49 min opposes GC 26 deg Sag 00 min

Carlo Rovelli: Venus 26 deg Gemini 30 min opposes GC 26 deg Sag 15 min,

[Jupiter 21 deg Leo 52 min conjunct Pluto_R 26 deg Leo 06 min] trine GC.

#Hubert Hugh Burke#AveryCanadianFilm#huberthughburke#Astrology#Werner Heisenberg#Wolfgang Pauli#Isaac Newton#John von Neumann#Max Born#Anthony Leggett#Carlo Rovelli#Albert Einstein#Quantum Foundations#Galactic Center#Script#Louis de Broglie#David Bohm#Erwin Schrödinger

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nowadays, we don’t tend to think of nuclear war as a climate problem, but concerns over these kinds of dangers were part of how modern climate change achieved political prominence in the first place. During the 1980s, a set of scientists raised the alarm about the effects of a nuclear winter and of the growing “hole in the ozone layer.” As the Stanford professor Paul N. Edwards writes in A Vast Machine, his magisterial history of climate modeling, these environmental issues taught the world that the planet’s entire atmosphere could come under threat at once, priming the public to understand the risks of global warming.

And even before that, climate science and nuclear-weapons engineering were twin disciplines of a sort. John von Neumann, a Princeton physicist and member of the Manhattan Project, took interest in the first programmable computer in 1945 because he hoped that it could solve two problems: the mechanics of a hydrogen-bomb explosion and the mathematical modeling of Earth’s climate. At the time, military interest in meteorology was high. Not only had a good weather forecast helped secure Allied victory on D-Day, but officials feared that weather manipulation would become a weapon in the unfolding Cold War.

The worst fears of that era, thankfully, never came to pass. Or at least, they haven’t happened yet. It is up to us to make sure that they don’t.

— Nuclear War Would Ravage the Planet’s Climate

#robinson meyer#nuclear war would ravage the planet's climate#history#military history#nuclear warfare#environmentalism#climate change#global warming#climatology#academia#engineering#nuclear engineering#weather modification#ww2#d-day#cold war#manhattan project#paul n. edwards#john von neumann#ozone layer

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

Decisions

I maintain nonetheless that we must ultimately conclude Sartre's whole philosophy is a bit numbing. People speak about analysis paralysis: I suppose that is the essence of Sartrianism.

Why do I like IT? Because it is animational. It gives a soul to the world. Sure, you can design eco-friendly power plants, but that is just going to throw more buildings into the world, buildings where nothing happens: on a computer, you can play games and music and you can watch movies or read books - animation. Of course, you're gonna wonder, what is the world going to be without the substance of carpentry, physics and chemistry? And the answer is: information. But we do need some substance of course, but I nevertheless feel that if we stop believing in computer science is the day we lose it.

Now for some philosophy: if the whole world consists of atoms, and robots could become infinitely more advanced, what makes it so that humans are sapient and computers are not? Maybe this is the killer question that is the reason religion seems so silly nowadays. We are starting to see that there is little magical about our bodies. We are just machines that are incredibly highly developed. Yet I instinctively feel there are tons of problems with that notion as well. Edsger Dijkstra said that the question whether machines can think is comparable to whether submarines can swim. Clearly, that invites us to think about really advanced water engines that can mimic swimming. So it really seems that thinking can become mechanized. Nevertheless, I gather something is faulty about this. Thinking is connected to mental activity, just like living, writing, reading, speaking and dancing. We have trouble assigning such notions to animals, even though we can see that animals do many lively activities. Despite that, we can't say that animals have minds like we do, simply because they don't speak. We usually ascribe this to their brain-capacity, but some animals with highly advanced brains don't seem to speak either, viz. the octopus or the elephant. Of course the notable exception is dancing. We do say that bees dance, sometimes. Also, singing is an exception, because we do say that whales sing. It seems we are just frantically guarding this notion of speech to keep ourselves in a position of superiority over the animals.

If animals can think, that says nothing about whether robots can think. A striking taciturnity. Kurt Vonnegut once quipped that we are on this Earth to "fart around", i.e. dilly-dally, which seems weirdly true - and maybe it is also a little tragic. Robots have a singular purpose. They can't skylark like humans can. However, we don't really have to do anything to animate the world. We just have to wake, or watch which is the same word. On the other hand, I think it is hard to stay awake when we've got nothing to do. And that brings us back to that primordial question: what to do? And I always answer this with: help people go on holidays. Of course, if everybody did that the world would descend into anarchy, but it can be all right for a while until you figure out what to do, I mean it really is an inexhaustible industry. The world is a dangerous place. Everybody needs to eat. But we can't all be farmers; that's how things used to be, sure, but people farm more efficiently now. I mean, I want to be better with IT, but I don't know if I'll aim at making money from it. Right now I work for the mail, but that can't last forever, and I don't want it to last forever. I don't even really enjoy it.

There was a time when people aimed at being polymaths, the homo universalis. Good in math, good in languages, good in arts, good in sports maybe even, maybe even good at warfare. Leonardo da Vinci is the most important exponent of this, and he wasn't probably that perfect in the last analysis; but I don't suppose polmathists want to be perfect, they just want to be cultivated. Cicero said you have to be a fool to dance. He also said that a house without books was a house without a soul. Certainly, conversation often consists merely of talk, but I do wonder if dancing cannot be a good way to animate the world. The Dutch author Gerard van het Reve said too that his books were meant to "liberate people from the material world." I've just made the same point for computers. But surely there is more to life than working and otiose conversation. But I don't study computer science to animate the world, I just do it because it clears my head. I just need to have something to fix my attention on. As I said, to animate the world, all you need do is wake (that is to say, watch). But I am not anti-religion or anything; you know religion does all these rituals right, that do seem to serve the purpose of animating the world. But it is probably not per se up to us to instigate such celebrations, which are beyond our control. Computers are simpler. That reminds of a quote by John von Neumann: people think mathematics is complicated because they don't realize how complicated life is. Yeah, it really seems like priest is such an interesting job. Doing those rituals really connects you to all those people, and you're personally involved in all those theological disputations that somehow connect to the things you do in the church: it's a lot. But, the real question is what is the soul of a city? Because obviously being a priest is peanuts compared to the vast totality of the society - even though I do think it is a fine job. And the thing is, you should just focus on the task at hand. Animation is not for nothing tied to silly children's entertainers. You could just do random things to animate the world, but that would be foolish, and you could draw silly faces and do weird things, but that would also be foolish. So it's best to just focus on the task at hand. Sometimes that will be IT, and sometimes that will be talking to your neighbour or enjoying a cup of tea. Or if you're a priest, it might be taking a confession from a vexed fellow.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Why did the computer scientist refuse to play hide and seek? Because good luck hiding when you're always in a superposition of states!

0 notes

Text

J. Robert Oppenheimer’s triumph was his tragedy. Oppenheimer had many achievements in theoretical physics but is remembered as the so-called father of the atomic bomb. Under his directorship, scientists at Los Alamos Laboratory, where the bomb was designed and built, forever changed how people view the world, adding a new sense of precariousness.

Oppenheimer’s life provides a human-scaled way to talk about an otherwise overwhelming topic. It’s little wonder that Christopher Nolan’s new film, “Oppenheimer,” tells the story of Los Alamos through this single life – or that Oppenheimer is the focus of so much writing about the bomb

In American culture, however, fascination with the man behind the bomb often seems to eclipse the horrific reality of nuclear weapons themselves – as if he were the welder’s glass allowing viewers to safely look at the explosion, even as it obscures the blinding light. Intense interest in Oppenheimer’s life and his ambivalent feelings about the bomb have turned him into almost a myth: a “tortured genius” or “tragic intellect” people try to comprehend because the terror of the bomb itself is too disturbing.

For the rest of his life, Oppenheimer gave the U.S. government’s justification of the atomic bombings: that they saved lives by preventing the need for invasion. But he conveyed a sense of anguish – scripting his own tragic role, as I argue in my book about him. “The physicists have known sin,” he remarked two years after the attacks, “and this is a knowledge which they cannot lose.”

‘Batter my heart’

The atomic bomb changed the meaning of the apocalypse. Where people had once pictured doomsday as an act of God’s wrath or final judgment, now a world could could be gone in an instant, with no sacred significance, no story of salvation. As physicist Isidor Isaac Rabi later said, the bomb “treated humans as matter,” nothing more.

But Oppenheimer pointedly used religious language when talking about the project, as if to underscore the weight of its significance.

The atomic bomb was first tested in the early morning of July 16, 1945, in the arid basin of southern New Mexico. Oppenheimer christened that test “Trinity,” referring to a sonnet by the English Renaissance writer John Donne, whose verses are famous for merging the sacred and the profane. “Batter my heart, three person’d God,” Donne pleads in “Holy Sonnet XIV,” asking God: “make me new.”

Later in life, Oppenheimer famously said that he had recalled words from the Bhagavad-Gita, a classical Hindu text, as he witnessed the sight and sound of the mushroom cloud: “I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds” – lines that originally described the Lord Krishna revealing his full power. According to Oppenheimer’s brother Frank, however, a physicist who was with him at the time, what they both said aloud was simply, “It worked.”

The contrast between their accounts speaks to the duality in Oppenheimer’s public image: a technical expert forging a weapon, and a poetic humanist burdened by the bomb’s moral significance. As a spokesperson and symbol of the Manhattan Project, Oppenheimer sometimes seemed to encourage the idea that it was his personal creation and responsibility. In fact, the bomb was the product of a gigantic scientific, engineering, industrial and military operation, one in which scientists sometimes felt like cogs in a machine. There really was no individual “father” of the atomic bomb.

Mathematician John von Neumann acerbically observed, “Some people profess guilt to claim credit for the sin.”

Describing the indescribable

Only weeks after the test, atomic bombs flattened the previously bustling cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. On Aug. 6 and Aug. 9, these cities suddenly ceased to be. Robert J. Lifton, an expert on the psychology of war, violence and trauma, called the Hiroshima survivors’ experience “death in life,” an encounter with the indescribable.

How does one represent what is beyond representation? In the film, Nolan recreates the intensity of the Trinity test with color and sound, following the bright flash with a pause and then the deep rumble and roar of the explosion and the clap of the shock wave. When it comes to Hiroshima and Nagasaki, however, he chooses to represent the attack without portraying it.

Drawing on a description in “American Prometheus,” the iconic biography of Oppenheimer on which the film was based, Nolan shows Oppenheimer’s triumphal speech in front of a cheering audience in the Los Alamos auditorium, announcing the destruction of Hiroshima by the weapon they had created.

Nolan creates a sense of dissociation, with the horror of the bomb entering the scene through flashbacks to the Trinity test and images of incinerated bodies from Hiroshima. The scientists’ cheering nightmarishly changes to wailing and weeping.

The bomb to end all wars?

After the end of the war, many of the scientists who had worked on the Manhattan Project sought to emphasize that the atomic bomb was not just another weapon. They argued that its tremendous danger should make war obsolete.

Among them, Oppenheimer carried the most authority as a result of his leadership of Los Alamos and his oratorical gifts. He pushed for arms control, playing the key role in drafting 1946’s Acheson-Lilienthal Report, a radical proposal that called for atomic energy to be placed under the control of the United Nations.

The form it ultimately took, known as the Baruch Plan, was rejected by the Soviet Union. Oppenheimer was bitterly disappointed, but U.S. atomic diplomats probably meant for it to be rejected – after all, the U.S. Navy was testing atomic bombs over the Bikini Atoll in the Pacific. Rather than seeing the bomb as the weapon to end all wars, the U.S. military seemed to treat it as its trump card. Nolan’s film includes a reference to the British physicist Patrick Blackett’s statement that the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was “not so much the last military act of the Second World War, as the first major operation of the cold diplomatic war with Russia.”

When the Soviets gained their own atomic bomb in 1949, Oppenheimer and his scientific advisory group opposed a proposal that the U.S. respond by pursuing the hydrogen bomb, a thousand times more powerful than the atomic bombs dropped on Japan. His opposition paved the way for Oppenheimer’s fall from political grace. Within a few years, both the U.S. and the Soviet Union had tested hydrogen bombs. The era of mutual assured destruction, when a nuclear attack would be certain to annihilate both superpowers, had begun. Today, nine nations have nuclear weapons – but 90% of them still belong to the U.S. and Russia.

Late in life, Oppenheimer was asked about the prospect of talks to limit the spread of nuclear weapons. “It’s 20 years too late,” he said. “It should have been done the day after Trinity.”'

#Oppenheimer#Los Alamos#The Manhattan Project#Christopher Nolan#Isidor Issac Rabi#Trinity test#John Donne#Holy Sonnet XIV#“Batter my heart three person-d God”#Frank Oppenheimer#Bhagavad Gita#Robert J. Lifton#John von Neumann#Patrick Blackett#Baruch Plan

1 note

·

View note

Text

At first he felt far from comfortable in the New World.

"Brighter than a Thousand Suns: A Personal History of the Atomic Scientists" - Robert Jungk, translated by James Cleugh

#book quote#brighter than a thousand suns#robert jungk#james cleugh#nonfiction#john von neumann#new world#uncomfortable#emigration

0 notes