#james travers

Text

A cool essay that compares two of the films we watched— Jean-Luc Godard's Alphaville, and Jean Cocteau's Orphée! Thanks @emmaetsesamis for the link. Read more here.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

#movies#polls#the invisible man#invisible man#30s movies#old hollywood#james whale#claude rains#gloria stuart#william harrigan#henry travers#requested#have you seen this movie poll

87 notes

·

View notes

Photo

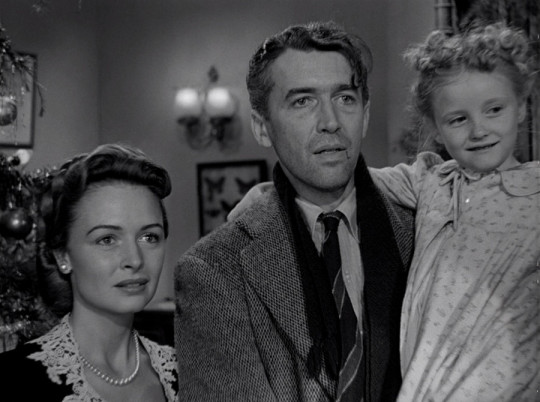

#its a wonderful life#ist das leben nicht schön#james stewart#donna reed#lionel barrymore#henry travers#thomas mitchell#frank capra

660 notes

·

View notes

Text

#The Invisible Man#Gloria Stuart#Claude Rains#William Harrigan#Dudley Digges#Una O'Connor#Henry Travers#Forrester Harvey#James Whale#1933

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

(Archive) Christmas movie of the day: It's a Wonderful Life (1946)

Originally posted: December 21st, 2021

Sometimes, Christmas alone isn't enough to bring the best out of us. Life isn't always easy on people and that won't stop being the case just because it's winter. Which is strangely enough the set up of, according to many, one of the most uplifting movies ever. A movie that despite not being completely timeless on it's every avenue it certainly still resonates with audiences, a feat that cannot be said for every movie that is 75 years old. Interestingly enough it isn't just a happy, go lucky film despite what it's reputation may make it sound like. No, it uplifts you. That means you have to be down so you can go up.

Disillusion, deception, despair and sacrifice are at the core of the movie; a man often being willing to sacrifice many chances of fulfilling his dreams so he can support others, constantly, frequently and substantially until reaching his breaking point. Even death rears it's head early on, showing a very simple strength for the film: it understands life is hard. This however doesn't mean the movie is bleak, nihilistic, or even humorless. In fact, the movie is befitting of it's name: it looks at life with enthusiasm and hope even with it's harshness.

A story about the power of altruism in the face of unfairness and injustice(Potter is just an evil capitalist incarnate), it shows hope against hope in a way that can be reinvigorating after times of duress for many(…even if it literally operates on a Deus Ex Machina with Clarence, the core message about helping others during times of need is still relevant).

That being said, there's plenty of this movie that has aged…ungracefully. The alternate fate of Mary is devoid of gravitas (or even that much logic) and there's lots of things that only make sense in the context of the 40's(like Mr. Gower being presented as sympathetic despite hitting kid George). Still, it's not hard to see why people still like this movie…except for Batman.

#roskirambles#christmas movies#frank capra#james stewart#donna reed#lionel barrymore#thomas mitchell#henry travers#beulah bondi#ward bond#frank faylen#gloria grahame#its a wonderful life

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

ℐ𝓃 𝒶 𝓃𝒶𝓉𝒾𝑜𝓃𝒶𝓁 𝓅𝒶𝓇𝓀 𝒾𝓃 𝓉𝒽𝑒 𝓃𝒶𝓉𝒾𝑜𝓃 𝑜𝒻 𝒦𝑒𝓃𝓎𝒶, 𝓉𝒽𝑒𝓇𝑒 𝒾𝓈 𝒶 ℬ𝓇𝒾𝓉𝒾𝓈𝒽 𝑔𝒶𝓂𝑒 𝓌𝒶𝓇𝒹𝑒𝓃 𝗚𝗲𝗼𝗿𝗴𝗲 𝗔𝗱𝗮𝗺𝘀𝗼𝗻 (𝐁𝐢𝐥𝐥 𝐓𝐫𝐚𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬) 𝒶𝓁𝑜𝓃𝑔 𝓌𝒾𝓉𝒽 𝒽𝒾𝓈 𝓌𝒾𝒻𝑒, 𝗝𝗼𝘆 𝗔𝗱𝗮𝗺𝘀𝗼𝗻 (𝐕𝐢𝐫𝐠𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐚 𝐌𝐜𝐊𝐞𝐧𝐧𝐚) 𝓉𝒶𝓀𝑒 𝒸𝒶𝓇𝑒 𝑜𝒻 3 𝑜𝓇𝓅𝒽𝒶𝓃𝑒𝒹 𝒷𝑒𝒶𝓊𝓉𝒾𝒻𝓊𝓁 𝓁𝒾𝑜𝓃 𝒸𝓊𝒷𝓈. ℒ𝒶𝓉𝑒𝓇 𝒶𝓈 𝓉𝒽𝑒 𝒸𝓊𝒷𝓈 𝑔𝓇𝑜𝓌 𝓉𝑜 𝒷𝒾𝑔 𝒶𝒹𝑜𝓁𝑒𝓈𝒸𝑒𝓃𝒸𝑒, 𝓉𝒽𝑒 𝓉𝓌𝑜 𝓁𝒶𝓇𝑔𝑒𝓇 𝑜𝒻 𝓉𝒽𝑒 𝓉𝒽𝓇𝑒𝑒 𝒸𝓊𝒷𝓈 𝑔𝑒𝓉 𝓈𝒽𝒾𝓅𝓅𝑒𝒹 𝒶𝓌𝒶𝓎 𝓉𝑜 𝒶 𝓏𝑜𝑜 𝒾𝓃 𝓉𝒽𝑒 𝒩𝑒𝓉𝒽𝑒𝓇𝓁𝒶𝓃𝒹𝓈, 𝓁𝑒𝒶𝓋𝒾𝓃𝑔 𝓉𝒽𝑒 𝓈𝓂𝒶𝓁𝓁𝑒𝓈𝓉 𝑜𝓃𝑒 𝓀𝓃𝑜𝓌𝓃 𝒶𝓈 𝗘𝗹𝘀𝗮 𝒷𝑒𝒽𝒾𝓃𝒹. 𝗠𝗿. 𝒜𝓃𝒹 𝗠𝗿𝘀. 𝗔𝗱𝗮𝗺𝘀𝗼𝗻 𝑔𝓇𝑜𝓌 𝓋𝑒𝓇𝓎 𝒻𝑜𝓃𝒹 𝑜𝒻 𝗘𝗹𝘀𝗮, 𝒷𝓊𝓉 𝓈𝑜𝓂𝑒𝓉𝒽𝒾𝓃𝑔 𝒹𝑒𝓋𝒾𝓈𝓉𝒶𝓉𝒾𝓃𝑔 𝒽𝒶𝓅𝓅𝑒𝓃𝓈 𝓌𝒽𝑒𝓃 𝓈𝒽𝑒 𝒾𝓈 𝒶𝒸𝒸𝓊𝓈𝑒𝒹 𝑜𝒻 𝒸𝒶𝓊𝓈𝒾𝓃𝑔 𝒶𝓃 𝑒𝓁𝑒𝓅𝒽𝒶𝓃𝓉 𝓈𝓉𝒶𝓂𝓅𝑒𝒹𝑒 𝒾𝓃 𝒶 𝓃𝑒𝒶𝓇𝒷𝓎 𝓋𝒾𝓁𝓁𝒶𝑔𝑒. 𝗝𝗼𝗵𝗻 𝗞𝗲𝗻𝗱𝗮𝗹𝗹 (𝐆𝐞𝐨𝐟𝐟𝐫𝐞𝐲 𝐊𝐞𝐞𝐧), 𝓉𝒽𝑒 𝒽𝑒𝒶𝒹 𝑔𝒶𝓂𝑒 𝓌𝒶𝓇𝒹𝑒𝓃 𝑜𝒻 𝓉𝒽𝑒 𝓅𝒶𝓇𝓀 𝑔𝒾𝓋𝑒𝓈 𝓉𝒽𝑒 𝗔𝗱𝗮𝗺𝘀𝗼𝗻'𝘀 𝒶 𝒹𝑒𝒸𝒾𝓈𝒾𝑜𝓃 𝓉𝑜 𝑒𝒾𝓉𝒽𝑒𝓇 𝓉𝓇𝒶𝒾𝓃 𝗘𝗹𝘀𝗮 𝓉𝑜 𝓁𝒾𝓋𝑒 𝓅𝓇𝑜𝓅𝑒𝓇𝓁𝓎 𝒶𝓂𝑜𝓃𝑔𝓈𝓉 𝒽𝓊𝓂𝒶𝓃𝓈, 𝑜𝓇 𝓇𝑒𝓉𝓊𝓇𝓃 𝒽𝑒𝓇 𝓉𝑜 𝓉𝒽𝑒 𝓌𝒾𝓁𝒹. ℐ 𝒶𝓂 𝒶 𝓁𝒾𝑜𝓃 𝓁𝑜𝓋𝑒𝓇, 𝓉𝒽𝑒𝓎'𝓇𝑒 𝓂𝓎 𝒻𝒶𝓋𝑜𝓇𝒾𝓉𝑒 𝒷𝒾𝑔 𝒸𝒶𝓉𝓈 𝑜𝒻 𝒶𝓁𝓁 𝓉𝒽𝑒 𝓁𝒶𝓇𝑔𝑒 𝒸𝒶𝓉 𝒷𝓇𝑒𝑒𝒹𝓈 𝒶𝓃𝒹 𝓑𝓸𝓻𝓷 𝓕𝓻𝓮𝓮 𝒾𝓈 𝒶 𝒷𝑒𝒶𝓊𝓉𝒾𝒻𝓊𝓁 𝓉𝑜𝓊𝒸𝒽𝒾𝓃𝑔 𝒻𝒾𝓁𝓂. 𝒯𝒽𝒾𝓈 𝒻𝒾𝓁𝓂 ℐ 𝓌𝑜𝓊𝓁𝒹 𝓇𝑒𝒸𝑜𝓂𝓂𝑒𝓃𝒹 𝓉𝑜 𝒶𝓃𝓎𝑜𝓃𝑒.

#Born Free (1966)#Adventure/Family#Virginia McKenna#Bill Travers ✝︎#Peter Lukoye ✝︎#Geoffrey Keen ✝︎#James Patrick Stuart#John Sibi-Okumu

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

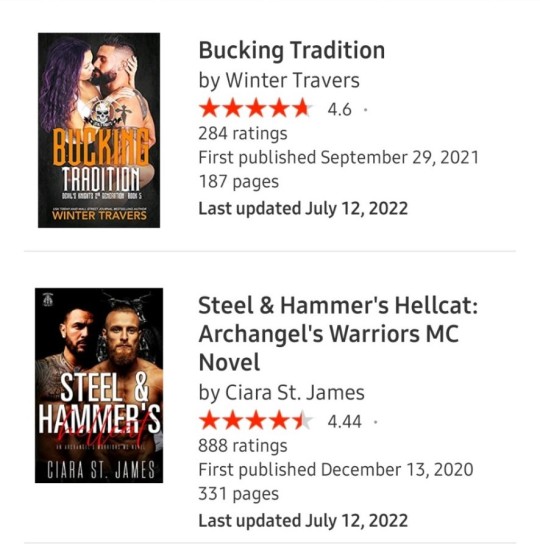

Currently Reading 💛

Bucking Tradition & Steel & Hammer’s Hellcat

#currently reading#reading#to read#read#booklr#bookblr#books#adult booklr#winter travers#bucking tradition#steel & hammer's hellcat#ciara st james#july 2022

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

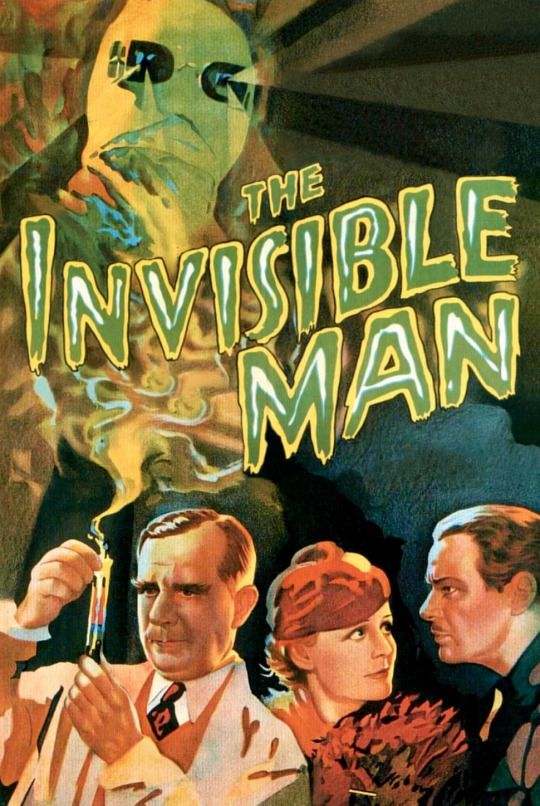

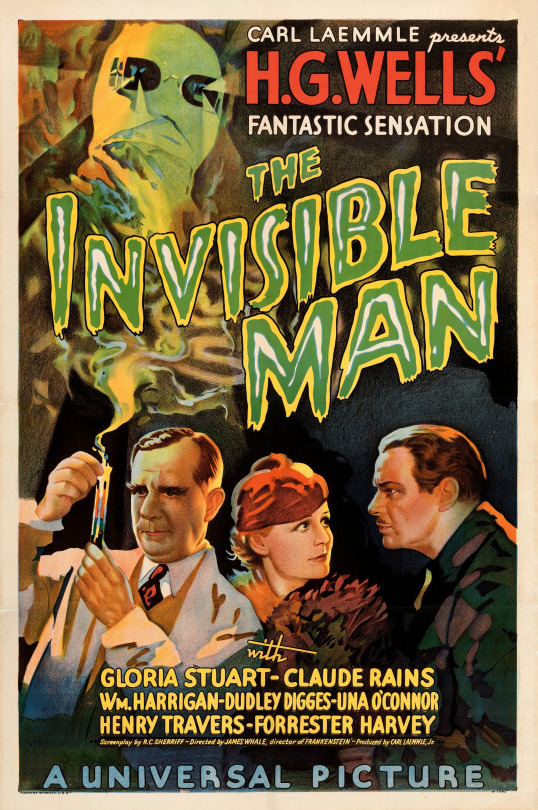

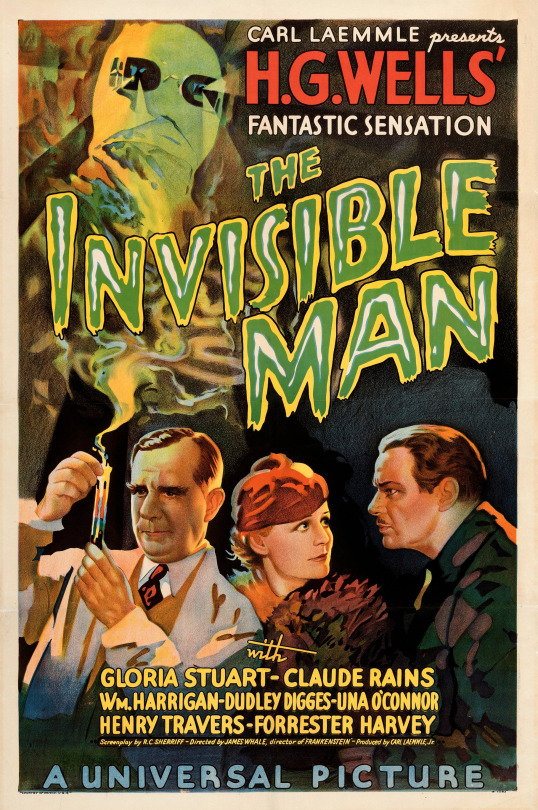

The Invisible Man (1933)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Borrowed Time (1939)

As time marches on, certain names that were once synonymous with American drama lose their weight, even among film buffs. In the early twentieth century, the Barrymore siblings – Ethel, John, and Lionel – were celebrated on both Broadway and in Hollywood, each one making a successful transition from the silent era to synchronized sound. The eldest, Lionel, was born in 1878 and was a Hollywood elder statesman when he made 1939’s On Borrowed Time. Directed by Harold S. Bucquet and based on a 1938 play of the same name by Paul Osborn (itself based on a 1937 Lawrence Edward Watkin novel of the same name), On Borrowed Time is a star vehicle for the eldest Barrymore. By the late 1930s, Barrymore had broken his hip twice – never healing properly. As such, he remained wheelchair-bound for the remainder of his life. Physical disablement, even in modern Hollywood, often curtails acting careers. But Barrymore’s home studio, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), often had their screenwriters find ways to incorporate Barrymore’s disability.

Lionel Barrymore was also in physical pain and depended on cocaine injections to work and sleep. However, this never affected his acting, as he delivers a wonderful lead performance in On Borrowed Time. Those less knowledgeable about this period in Hollywood history will probably only recognize his surname and the acting family he came from. Nowadays, most cinephiles probably only know of Lionel Barrymore through It’s a Wonderful Life (1946; Barrymore played the villainous Mr. Potter). Lionel Barrymore's role as the somewhat foul-mouthed but caring grandfather here offers something completely different.

Mr. Brink (Cedric Hardwicke) is hitchhiking somewhere near a small town in contemporary America. But he is not interested in riding with just anyone:

MAN IN CONVERTIBLE: May I give you a lift, sir?

MR. BRINK: Thank you, no. I have an appointment – a lady and gentleman.

MAN IN CONVERTIBLE: Oh, I’m sorry. [coughs] I thought you signaled me.

MR. BRINK: No. Not yet...

As you may have guessed, Mr. Brink is a personification of death. A few minutes later, he flags down that lady and gentleman and takes their lives in a car accident. That couple are the parents of John “Pud” Northrup (Bobs Watson; best known as Pee Wee in 1938’s Boys Town), who will now live solely under the care of Gramps and Granny (Barrymore and Beulah Bondi) and their housemaid Marcia (Una Merkel). At the memorial service for Pud’s parents, Gramps donates a substantial sum to the church. After learning of Gramps’ generosity, Pud exclaims that his grandfather doing such a good deed should allow him a wish. Gramps’ wish: as a deterrence local children stealing his apples, he wishes that anyone who climbs up his apple tree will be stuck there until he permits them down. Some time later, Mr. Brink arrives at Northrup grandparent homestead for an appointment with Gramps. Gramps tricks Mr. Brink up the apple tree, trapping him there – setting off a series of developments that put Gramps in a moral bind.

In a cast already headlined by character actors, how about some more? On Borrowed Time also features Henry Travers (the guardian angel Clarence in It’s a Wonderful Life) and Nat Pendleton as neighbors, Grant Mitchell as Gramps’ lawyer, James Burke as the sheriff, Charles Waldron as the reverend, and an uncredited Hans Conried (Captain Hook and Mr. Darling in 1953’s Peter Pan) as the man in the convertible.

Elsewhere, away from the camera, one can’t find much of composer Franz Waxman’s (1935’s Bride of Frankenstein, 1951’s A Place in the Sun) string-dominated score anywhere, but this is one of Waxman’s finest scores of his early career.

The opening half-hour of On Borrowed Time are its weakest. Hardwicke’s Mr. Brink has an eerily charismatic first impression that the scenes immediately following it cannot hope to match. Instead of learning more about the nature of Mr. Brink, the film instead shows us some of Pud’s misadventures and his relationship with his grandparents. Strangely, the loss of his parents seems to have had little effect on Pud at all, although his sadness seems to emerge in his contentious relationships with the other local boys and Aunt Demetria (Eily Malyon). Aunt Demetria, shortly after the Northrup parents’ deaths, hatches a scheme to assume guardianship of Pud and attain access to his considerable inheritance. Her designs are so obvious to all that when Gramps and Pud start calling her a “pismire” (literally, a pissing ant), Granny looks the other way when she might otherwise correct their boorish behavior. All of this takes longer to develop than it should (it does not help that Bobs Watson’s performance as Pud feels disjointed, but more on that shortly), even if the opening act primarily serves to show us how close Pud is to his grandparents. Even though we sense where the dramatic stakes are headed, On Borrowed Time almost seems to splinter into another film before we see Mr. Brink again.

In addition, contemporary reviews of On Borrowed Time lambasted screenwriters Alice D.G. Miller (1929’s The Bridge of San Luis Rey) and Frank O’Neill (no other film credits) for sanitizing the language from the original stage play due to the demands of the Hays Code (the self-censorship code that applied to major Hollywood studios from 1934-1968, repealed in favor of the current MPA ratings system). For the record, the text of the stage play was not freely available as I was writing this piece, so I have no means of comparison. Paul Osborn’s On Borrowed Time has only appeared on Broadway thrice: the 1938 original production and short-lived revivals in 1953 and 1991. The play had also been adapted for radio and television.

Compared to those film reviewers during the film’s 1939 release and many modern writers, I tend to be more forgiving if the Hays Code-enforced changes to a film do not significantly alter the spirit of the text. Sure, it would be funnier to hear disparaging language stronger than “pismire” in a 1939 film, but Pud’s and Gramps’ feelings towards Aunt Demetria, the apple-stealing boys, and Mr. Brink are comprehensible in this movie.

The closing two acts of On Borrowed Time draw its strengths from the performances and the narrative’s adoption of fairy tale logic (any film beginning with death flagging down folks he has an “appointment” with is almost always operating under the terms of the fantasy genre). In tandem, Lionel Barrymore and Bobs Watson’s good-humored and loving rapport lift the film above its structural flaws. Barrymore’s Gramps – an American Civil War and Spanish-American War veteran* – is a classic small town curmudgeon, only allowing his bitter exterior to crumble when Granny and Pud are around. Looking to protect Pud from Aunt Demetria, Gramps remains defiant towards the wills of Mr. Brink and the insistent neighbors. Perhaps it is not the greatest Lionel Barrymore performance, but he is always effective.

Bobs Watson, as Pud, is inconsistent anytime he does not share the scene with Barrymore. The explanation for his performance comes from Watson himself: “My dad was the one that really directed me, and I think some of the directors resented it a little bit… I trusted my dad implicitly, so I read the dialogue the way he told me.” His father’s influence results in occasionally overcooked line readings against director Harold S. Bucquet’s vision (MGM’s Dr. Kildare series, 1943’s The Adventures of Tartu), more theatrical than what the scene calls for. But when the scene calls for crying, by golly can Watson (who had a reputation for crying on cue) deliver. And his scenes with Barrymore are beautifully acted, convincingly showing the audience the love between grandson and grandfather.

Sir Cedric Hardwicke, a noted Shakespearean actor, cuts no corners as Mr. Brink. Mr. Brink is aware that, in time, he will keep all his appointments. Hardwicke plays Brink as slightly menacing, always dignified (no one expects that perfect an English accent in rural America), and somewhat aloof to what he probably thinks are childish trivialities and life’s mundane moments. He is the antagonist, but in no way is he the villain of this movie. That belongs to Eily Malyon as Aunt Demetria, a character some compare to Margaret Hamilton’s Mrs. Gulch/Wicked Witch from The Wizard of Oz (1939; released a little more than a month after On Borrowed Time) due to her temperament and unbending nature. One wishes the film made more use of the always-underappreciated Beulah Bondi as Granny (Bondi very often played elderly mothers and grandmothers, almost always appearing much older than she actually was), too.

Death and loss are two themes currently popular in modern cinema (see: a vast bulk of Pixar’s filmography, 2016’s Manchester by the Sea, 2019’s The Farewell, and a large selection of pieces from any film festival worldwide), but in the early decades of talkies in Hollywood, you would be hard-pressed to find films in which those themes were truly central, not secondary, to the narrative. And when those themes do appear, they appear in the context of fantasy films, like Death Takes a Holiday (1934) and On Borrowed Time. Anecdotally, I suspect the scarcity of major Hollywood movies revolving around death and loss is partly due to the realities of the 1930s and 1940s. Audiences, concerned with a worldwide Great Depression and soon a Second World War, did not seek films ruminating about death and loss and sought escapist fare instead. There was enough despair to go around.

The film that emerges on the back of these performances is thanks to its ability not to concentrate on the fantastical situation the Gramps and Pud find themselves in, but to raise the moral questions that Mr. Brink’s presence – and eventual entrapment – poses. Mr. Brink’s time in the tree results in consequences that Gramps and Pud could not imagine. Gramps’ decision to delay his death for the love of his grandson is concurrently noble and selfish. It is noble in respect to wanting the best for Pud, so that he may live life away from his aunt’s icy attitude and pernicious designs regarding her nephew’s inheritance. But it is selfish in that, as Gramps learns, that Brink’s inability to make any appointments unless he comes down from the apple tree means that almost no living being can die (for spoiler reasons, I am not listing the exceptions here) – even the ones in physical pain. How is Gramps supposed to navigate this situation, in addition to the communal and legal pressures from his neighbors and the police?

A resolution comes abruptly, in a way that devastates Gramps (but would probably make the Brothers Grimm nod in appreciation). On Borrowed Time’s bittersweet ending is deserved, and – as long as the viewer accepts the film’s fantastical premise and rules – will play quite differently for audiences of different ages.

Lionel Barrymore had two daughters with Doris Rankin, his first wife. Barrymore and Rankin lost both daughters in their infancies; neither ever truly recovered from their losses. One wonders what Barrymore thought while making On Borrowed Time, a film that argues for one coming to terms with death, however unfair or untimely its arrival. For a 1939 release (a legendarily glorious year for American cinema), positioning such ideas as the film’s narrative keystone ensures On Borrowed Time a unique spot in the early years of Hollywood’s Golden Age.

My rating: 8/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found in the “Ratings system” page on my blog. Half-points are always rounded down.

* Gramps describes himself as having fought for the Union. This might make Gramps close to ninety years old, give or take, if we are to believe the film’s self-professed setting!

For more of my reviews tagged “My Movie Odyssey”, check out the tag of the same name on my blog.

NOTE: This is the 800th full-length Movie Odyssey review I have published on tumblr.

#On Borrowed Time#Harold S. Bucquet#Lionel Barrymore#Beulah Bondi#Cedric Hardwicke#Bobs Watson#Una Merkel#Nat Pendleton#Henry Travers#Grant Mitchell#Eily Malyon#James Burke#Charles Waldron#Alice D.G. Miller#Frank O'Neill#Lawrence Edward Watkin#Paul Osborn#Franz Waxman#TCM#My Movie Odyssey

0 notes

Text

The Saint: The People Importers (6.13, ITC, 1968)

"We must have met before."

"It certainly seems long overdue."

"You're Simon Templar."

"Right. And you?"

"Laura Stevens. I've heard a lot about you. You're said to be very rich."

"Oh, a man's enemies will go to any lengths to blacken his character."

#the saint#the people importers#itc#1968#leslie charteris#donald james#ray austin#roger moore#neil hallett#susan travers#gary miller#ray lonnen#salmaan peerzada#imogen hassall#nik zaran#joan newell#michael robbins#ron pember#julian sherrier#jeremy anthony#kevork malikyan#the saint takes on illegal immigration and im happy to say the ep is broadly sympathetic towards the plight of the actual immigrants (as#was other 60s tv to its credit; see similar eps of Special Branch and Softly Softly). Simon even chastises a faintly racist police officer#in one scene. plus the show actually cast asian actors which is a low bar but one it's waltzed under before.. yes this isn't bad at all.#Simon notably takes an instant dislike to the villain (and assumes correctly that he IS the villain) based purely on his wearing a club#blazer and being kind of posh; a weird bias considering how many of Simon's friends have been shown to be 'good old boy' public school#types in past eps. speaking of‚ he also mocks the bad guy for being a ww2 vet (???) implying that he's old and past it; the show has#apparently forgotten that per a very early s1 ep Simon himself fought with the French resistance during ww2 (are they retconning his age?)#musician Gary Miller takes a rare acting role here but died suddenly of a heart attack during production: you can spot which scenes have#been completed with a stand in but if i hadn't known I'm not sure i would have‚ the team managed fairly well.

1 note

·

View note

Text

It’s a Wonderful Life (1946)

Everyone knows what It’s a Wonderful Life is about. How many times have we seen a television series ape its story? The protagonist is at their lowest, they begin believing things would be better if they had never been born, some otherworldly presence comes to show them otherwise. That is what happens in this 1946 classic but it’s also an oversimplification. Until you’ve sat down and actually watched it, you have no idea what this movie is actually about.

All his life, George Bailey (James Stewart) has wanted to travel the world. Unfortunately, his selflessness and responsibilities have prevented him from leaving Bedford Falls. Eventually, he inherits the responsibility of running the Bailey Brothers Building and Loan - a small bank that welcomes anyone who doesn’t want to go to the greedy Henry F. Potter (Lionel Barrymore). When the bank’s funds go missing, he loses all hope and contemplates suicide.

There’s much more to this story than its central conflict. A major portion of the plot concerns the romance between George and Mary Hatch (Donna Reed), the woman who’s had a crush on him since they were young. Their first date has the kind of moments that will remind you why you fell for the guy/gal next to you. What Mary saw in George back then and what she does now is so obvious. Money-wise, he may be poor but in spirit and in friends, he’s rich.

James Stewart is so good in this role. He’s cheery and easy to laugh with but there’s always a hint of sadness right there, behind the main thing. Over and over, you see George slice a little bit off the top and give it to someone who needs it. What he has left is meagre but he always manages and although he doesn’t realize it, we - and everyone who’s ever met him - recognize him as a hero. Not the kind that wins medals; those you only need during extraordinary circumstances. George Bailey is the everyday kind of hero, the kind who refuses to compromise even when raising his hand and speaking out could be to his detriment. Opposing him at seemingly every turn are normal, everyday injustices, unfortunate chance, and greed, all of which Henry F. Potter embodies. You hate Potter because he’s so real. You know there are people just like him everywhere and there are far too few George Baileys to stand up to them.

If you go into the film for its iconic Christmas scenes in which everything goes wrong and George prepares to make a decision from which there is no turning back, you’ll be waiting a while. The picture is over two hours, with the bulk of it focussing solely on George, his relationship with Mary, their family, and the town that comes to love him. If you're going in just to see George's guardian angel, Clarence (Henry Travers) show him how he has touched the lives of the Bedford Falls community, It's a Wonderful Life can feel long. It’s one of those cases where the film’s reputation doesn’t do it any favours because you expect one thing and get something else. Once you get over that initial shock, however, you’re completely won over. After seeing George work hard to do what’s right every day, no matter what, you want more than anything for him to see what you see. Everyone wants to believe they matter. Being shown first-hand how much good one person can do lifts your heart. You might not be George Bailey, but you might be half of one and that’s still pretty great.

It’s a Wonderful Life is a deeply moving film. It highlights humanity’s very best qualities. It’s also romantic, occasionally funny, wonderfully acted and full of life. The characters feel like real people, people you’ve met before, collected together to tell you this very personal message. It takes no effort for you to set aside your initial disappointment because while Frank Capra’s most iconic film (that’s saying something) might not be the movie you think it is going in, it is the movie you want it to be by the end. (On Blu-ray, December 13, 2020)

#It's a Wonderful Life#movies#films#movie reviews#film reviews#Christmas movies#Christmas Films#Frank Capra#Frances Goodrich#Albert Hackett#The Greatest Gift#Philip Van Doren Stern#James Stewart#Donna Reed#Lionel Barrymore#Thomas Mitchell#Henry Travers#Beulah Bondi#Ward Bond#Frank Faylen#Gloria Grahame#1946 movies#1946 films

0 notes

Text

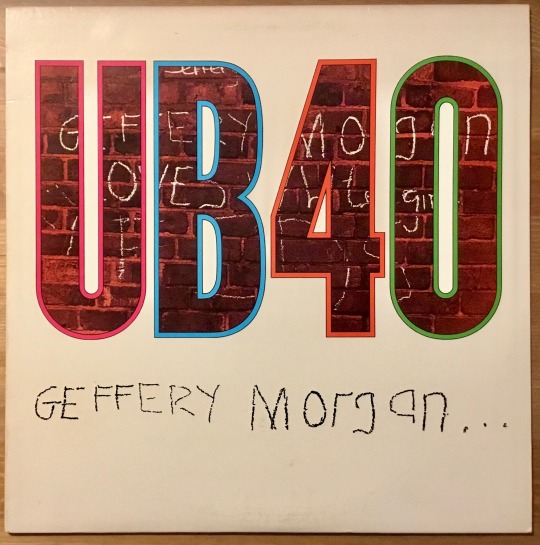

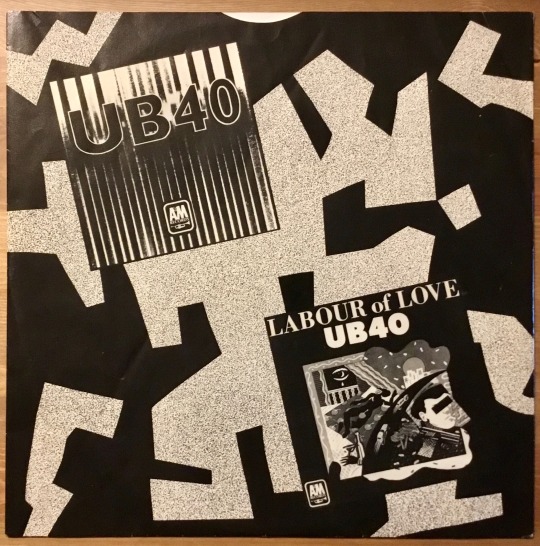

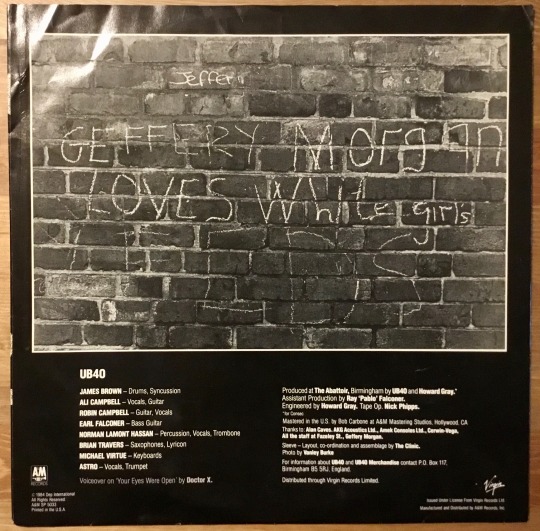

Album # 862 UB40: Geoffrey Morgan (1984)

A&M Records

#ub40#james brown#ali campbell#robin campbell#earl falconer#norman lamont hassan#brian travers#michael virtue#astro#a&m records#reggae#electronic music#synth pop#80’s rock#my vinyl playlist#record cover#album cover#album art#vinyl records

0 notes

Photo

#its a wonderful life#ist das leben nicht schön#james stewart#donna reed#lionel barrymore#henry travers#thomas mitchell#virginia patton#frank capra

69 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#it's a wonderful life#james stewart#donna reed#lionel barrymore#thomas mitchell#henry travers#beulah bondi#ward bond#frank faylen#gloria grahame#frank capra#1946

2 notes

·

View notes

Conversation

Brynn: Acting like a fool won't solve your problems

James: Well then we have no hope at all!

0 notes

Text

Sudden revelation paid Bobby Moch a visit as well. His came as he sat, in the shade under a tree in a wide-open field on Travers Island, opening an enve-lope. The envelope contained a letter from his father, the letter Bobby had re quested, listing the addresses of the relatives he hoped to visit in Europe. But the envelope also contained a second, sealed, envelope labeled, "Read this in a private place." Now, alarmed, sitting under the tree. Moch opened the second envelope and read its contents. By the time he had finished reading, tears were running down his face.

The news was innocuous enough by twenty-first-century standards, but in the context of social attitudes in America in the 193os it came as a profound shock. When he met his relatives in Europe, Gaston Moch told his son, he was going to learn for the first time that he and his family were Jewish.

Bobby sat under the tree, brooding for a long while, not because he suddenly found himself a member of what was then still a much discriminated against minority, but because as he absorbed the news he realized for the first time the terrible pain his father must have carried silently within him for so many years. For decades, his father had felt that in order to make it in America it was necessary to conceal an essential element of his identity from his friends, his neighbors, and even his own children. Bobby had been brought up to believe that everyone should be treated according to his actions and his character, not according to stereotypes. It was his father himself who had taught him that. Now it came as a searing revelation that his father had not felt safe enough to live by that same simple proposition, that he had kept his heritage hidden painfully away, a secret to be ashamed of, even in America, even from his own beloved son.

— The Boys in the Boat by Daniel James Brown

#and then can you imagine having to gk to Berlin for the Olympics immediately after finding out????#where there was already tons antisemitic legislation in place??#AND PEOPLE MURDERED FOR BEING JEWISH??!!#the boys in the boat#quotes#book quotes#bobby moch#Bobby Moch needs a hug#real tbitb

20 notes

·

View notes