#it was written in protest of the Mexican American war

Note

Literally hard for me to believe so many of the “I feel guilty for being white in America” people are also the “but I don’t feel guilty about my choice of job for a #1 arms manufacture. Gotta do what you gotta do!”

But the soul is still oracular, amidst the market's din/

List the ominous stern whisper from the Delphic cave within:/

They enslave their children's children who make compromise with sin.

#i agree with you anon#i just have been thinking of that bit of that poem for the past few days#RE complicity and compromise#from The Present Crisis by James Russell Lowell#it was written in protest of the Mexican American war#and later became the namesake of the NAACPs magazine The Crisis in 1910

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 9.28 (before 1940)

48 BC – Pompey disembarks at Pelusium upon arriving in Egypt, whereupon he is assassinated by order of King Ptolemy XIII.

235 – Pope Pontian resigns. He is exiled to the mines of Sardinia, along with Hippolytus of Rome.

351 – Constantius II defeats the usurper Magnentius.

365 – Roman usurper Procopius bribes two legions passing by Constantinople, and proclaims himself emperor.

935 – Duke Wenceslaus I of Bohemia is murdered by a group of nobles led by his brother Boleslaus I, who succeeds him.

995 – Boleslaus II, Duke of Bohemia, kills most members of the rival Slavník dynasty.

1066 – William the Conqueror lands in England, beginning the Norman conquest.

1106 – King Henry I of England defeats his brother Robert Curthose at the Battle of Tinchebray.

1238 – King James I of Aragon conquers Valencia from the Moors. Shortly thereafter, he proclaims himself king of Valencia.

1322 – Louis IV, Holy Roman Emperor, defeats Frederick I of Austria in the Battle of Mühldorf.

1538 – Ottoman–Venetian War: The Ottoman Navy scores a decisive victory over a Holy League fleet in the Battle of Preveza.

1542 – Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo of Portugal arrives at what is now San Diego, California. He is the first European in California.

1779 – American Revolution: Samuel Huntington is elected President of the Continental Congress, succeeding John Jay.

1781 – American Revolution: French and American forces backed by a French fleet begin the siege of Yorktown.

1787 – The Congress of the Confederation votes to send the newly written United States Constitution to the state legislatures for approval.

1821 – The Declaration of Independence of the Mexican Empire is drafted. It will be made public on 13 October.

1844 – Oscar I of Sweden–Norway is crowned king of Sweden.

1867 – Toronto becomes the capital of Ontario, having also been the capital of Ontario's predecessors since 1796.

1868 – The Battle of Alcolea causes Queen Isabella II of Spain to flee to France.

1871 – The Brazilian Parliament passes a law that frees all children thereafter born to slaves, and all government-owned slaves.

1889 – The General Conference on Weights and Measures (CGPM) defines the length of a metre.

1892 – The first night game for American football takes place in a contest between Wyoming Seminary and Mansfield State Normal.

1893 – Foundation of the Portuguese football club FC Porto.

1901 – Philippine–American War: Filipino guerrillas kill more than forty American soldiers while losing 28 of their own.

1912 – The Ulster Covenant is signed by some 500,000 Ulster Protestant Unionists in opposition to the Third Irish Home Rule Bill.

1912 – Corporal Frank S. Scott of the United States Army becomes the first enlisted man to die in an airplane crash.

1918 – World War I: The Fifth Battle of Ypres begins.

1919 – Race riots begin in Omaha, Nebraska.

1924 – The first aerial circumnavigation is completed by a team from the US Army.

1928 – Alexander Fleming notices a bacteria-killing mold growing in his laboratory, discovering what later became known as penicillin.

1939 – World War II: Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union agree on a division of Poland.

1939 – World War II: The siege of Warsaw comes to an end.

0 notes

Text

"Once to Every Man and Nation" is such a sad, sad hymn. It was originally written in protest against the annexation of Texas, with how that empowered US slave states, and later against the American land-grab from the Mexican-American War - both the inherent imperialism, and the fear of the newly-conquered states becoming even more slave states. The lyrics don't directly reference slavery or imperialism, however, and the song could be applied to most any injustice where people have either been murdered and martyred, or have willingly sacrificed their life's blood in holy and mortal battle against the forces of oppression.

1 note

·

View note

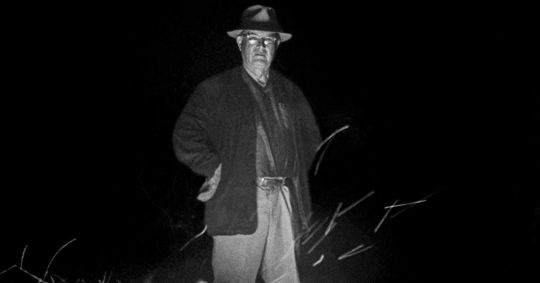

Photo

While actor/director Orson Welles is mostly known these days for Citizen Kane, his infamous War of the World’s radio play, performing in a Transformers movie, and starting an argument over peas, but what is less well known is his work as a social commentator and activist.

Indeed, while his critique of the wealthy in Citizen Kane got him put on a watch-list by the FBI, Welles had been involved in trying to help diversify theatre since 1936, when he worked with an all African American acting company in an adaptation of MacBeth which managed to both win over Shakespeare purists and local activists in Harlem who suspected that Welles was going help made the production insulting towards the actors and the surrounding community.

And in a 1944 column for Free World he talked about the need for social justice and called for "race hate” to be criminalised. The article itself is interesting, especially considering when it was written, here’s a taste:

Race hate isn’t human nature; race hate is the abandonment of human nature. But this is true: we hate whom we hurt and we mistrust whom we betray. There are minority problems simply because minority races are often wronged. Race hate, distilled from the suspicions of ignorance, takes its welcome from the impotent and the godless, comforting these with hellish parodies of what they’ve lost—arrogance to take the place of price, contempt to occupy the spirit emptied of the love of man. There are alibis for the phenomenon—excuses, economic and social—but the brutal fact is simply this: where the racist lie is acceptable there is corruption. Where there is hate there is shame. The human soul receives race hate only in the sickness of guilt.

The Indian is on our conscience, the Negro is on our conscience, the Chinese and the Mexican-American are on our conscience. The Jew is on the conscience of Europe, but our neglect gives us communion in that guilt, so that there dances even here the lunatic spectre of anti-semitism.

This is deplored; it must be fought, and the fight must be won.

The poll tax is regretted; it must be abolished.

And poll tax thinking must be outlawed. This is a time for action. We know that for some ears even the word “action” has a revolutionary twang, and it won’t surprise us if we’re accused in some quarters of inciting to riot. FREE WORLD is very interested in riots. FREE WORLD is very interested in avoiding them.

We call for action against the cause of riots. Law is the best action, the most decisive. We call for laws, then, prohibiting what moral judgment already counts as lawlessness. American law forbids a man the right to take away anothers right. It must be law that groups of men can’t use the machinery of our Republic to limit the rights of other groups—that the vote, for instance, can’t be used to take away the vote.

Additionally, in his 1945 to 46 radio show Orson Welles Commentaries, he used the opportunity to talk about current events, including protesting the 1946 Bikini Atoll atomic test, speaking out against the dissolution of the Office of Price Administration (a service started during World War Two to control prices and rent), and most prominently, denouncing the 1946 assault on African American WWII veteran Isaac Woodard by some white cops in South Carolina.

Woodard was traveling from South Carolina to Georgia by bus, and hours after being honorably discharged, Batesburg (now Batesburg-Leesville) police chief Lynwood Shull and several over officers beat and blinded Woodard after attempting to rob him of $700 (his military pay), fined him $50, and left his injuries untreated so his family were not able to find him until weeks after the attack due to Woodward loosing his memory in addition to his sight.

Initially the NAACP brought the news of the attack to socially progressive news papers and black press, but the organization's Executive Secretary Walter White and cartoonist Ollie Harrington (recently tasked with building out the NAACP's public relations) wanted the assault to become national news, so they wrote a letter to Orson explaining what’s up.

And, indeed, with an affidavit from Woodward, Welles read an account by the man about the circumstances leading up to his assault, the attach and the resulting aftermath. The NAACP’s plan to bring Woodward’s attack to a wider international audience succeeded, with Welles covering the subject for four episodes in total and explicitly comparing the conduct of Shull and his men to that of the Nazis in the first episode.

"The boy saw him while he could still see, but of course he had no way of knowing what particular policeman it was who brought the justice of Dachau and Oswiecim to Aiken, South Carolina," Welles said in that first broadcast. "He was just another white man with a stick, who wanted to teach a Negro boy a lesson—to show a Negro boy where he belonged: In the darkness."

Naming the policeman Officer X, Welles addressed him directly. "Wash your hands, Officer X. Wash them well. Scrub and scour, you won't blot out the blood of a blinded war veteran," Welles said. "Go on, suckle your anonymous moment while it lasts. You're going to be uncovered. We will blast out your name! We'll give the world your given name, Officer X. Yes, and your so-called Christian name. It's going to rise out of the filthy deep like the dead thing it is."

Welles and the NAACP subsequently worked out the names of the officers responsible, and pressured for Shull and his men to be prosecuted by the Truman administration. And, surprisingly, Harry Truman actually agreed and the racist cops were put on trial for their crime...

...And were found innocent by an all-white jury within 30 minutes. While a pro-segregationist congressman attempted to appeal to J. Edgar Hoover for the FBI to investigate Welles and in his “inflammatory broadcasts“.

The week following the final episode based on Woodard’s case, ABC informed Welles that they were cancelling his show, which would finish airing October 6, 1946.

Despite the lack of success in prosecuting the cops, however, the NAACP had brought enough national attention to the issue of police violence against the African American community to lead Truman establishing the Civil Rights Commission. Additionally, in July 1948 Truman issued two Executive Orders, banning racial discrimination in the military and desegregating the federal government.

Following the trial, Woodard would move to New York City, where he would eventually die in a Veterans Hospital in the Bronx in 1995. Shull would die in his hometown of Batesburg several years later at the age of 95, having faced no legal consequences for his actions.

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

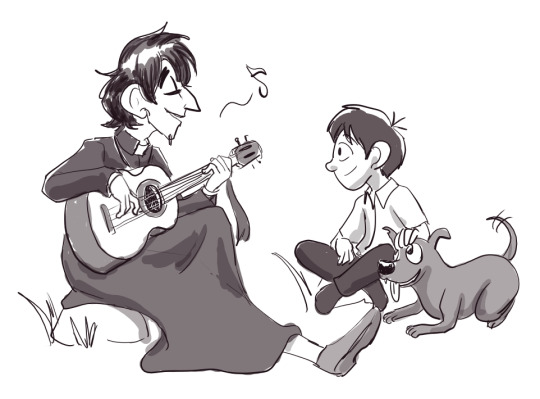

[Coco] Nuestra Iglesia, Pt 21

Title: Nuestra Iglesia

Summary: Fake Priest AU. In the midst of the Mexican Revolution, Santa Cecilia is still a relatively safe place; all a young orphan named Miguel has to worry about is how to get novices Héctor and Imelda to switch their religious vows for wedding vows before it’s too late. He’s not having much success until he finds an unlikely ally in their new parish priest, who just arrived from out of town.

Fine, so Padre Ernesto is a really odd priest. He’s probably not even a real priest, and the army-issued pistol he carries is more than slightly worrying. But he agrees that Héctor and Imelda would be wasted on religious life, and Miguel will take all the help he can get.

It’s either the best idea he’s ever had, or the worst.

Characters: Miguel Rivera, Ernesto de la Cruz, Héctor Rivera, Imelda Rivera, Chicharrón, Óscar and Felipe Rivera, OCs. Imector.

Rating: T

[All chapters up are tagged as ‘fake priest au’ on my blog.]

A/N: First off, unlike Ernesto, I gotta give some credit! The song that features in this chapter was written by @eldathe, who has a gift I sorely lack (but whom I'll definitely not murder for it).

Also, @lunaescribe wrote the bulk of the scene in which Ernesto and John discuss the scriptures. I only made some minor edits with her permission (watch and learn, Ernesto).

Art is by @swanpit, who is a gift as always!

***

“So it… worked? It actually worked?”

“Why the surprise? I told you I could sell it.”

Sofía made a point to cross her arms and look just a little insulted, but she didn’t really put a lot of effort in it: relief was too great. Sure, she had been pretty certain she’d managed to back the gringo into a corner and force him to keep the secret, but she couldn’t entirely discount the chance he’d decide screwing Ernesto over was more important.

“Right, right-- you did a great job,” Héctor replied, laughing a little in sheer glee. “Well, it’s sorted! We’re safe!”

Imelda rolled her eyes. “From the Federales, yes. Not from boredom now that Juan will be the one to say mass.”

“Let’s be honest, Sunday mass was never a party when Padre Edmundo led it, and we somehow survived.”

“Fair enough.”

“Huh, Ernesto? Why the long face?” Héctor spoke up, blinking. Now that he mentioned, Ernesto did rather look like he’d just announced Juan had opted to personally hang him in the plaza first thing after the evening mass.

As a response, Ernesto made a face. “He wants me to study the Bible.”

“Well, there are worse punishments--”

“And learn Latin.”

“... Ah.”

“Oh.”

“My condolences.”

“Would you like me to send a telegram now for the Federales to come pick you up at their earliest convenience?”

Ernesto scoffed. “You know, this is the part where you’re supposed to be telling me Latin is not too bad.”

“But it is,” Héctor said, matter-of-factly.

“What, you’d have me lie to you?” Sofía gasped in moc horror, hand to her mouth. “Me? A nun?”

“... I hate all of you,” Ernesto informed them, only to yelp and laugh when Héctor threw an arm around his shoulders and ruffled his carefully combed hair.

“Ay, don’t be like that. We survived it, and you will too,” he declared. “But I have just the thing that will make you feel better!”

“You managed to sneak in a bottle of tequila?”

“Better - I have an idea for a new song, and I know you’re going to love it.”

“Hah! If I’m left with any free time for music now.”

“Well, Juan is going to be busy, no? Saying mass and confessing and whatnot. He can’t be watching you all the time,” Héctor pointed out, and patted his shoulder. “... It’s good to know you’re safe.”

Ernesto chuckled, reaching up to fix his hair. “We all are.” The rest of the sentence - for now - hung unspoken in the air, but none of them said anything. In the end, it was Héctor to speak.

“Well-- I’ll go looking for Miguel. I need to talk to him. And don’t you think I forgot you also owe him an apology,” he added, jabbing a finger against Ernesto’s chest before he was off... though not without giving Imelda a dreamy smile as he left the room. Ernesto scoffed.

“What, is apologizing is my new job now?” he called out, but none of them bothered to reply.

***

Héctor found Miguel at the stream, throwing flat rocks over the water and trying to make them bounce all the way down to the bridge while Dante jumped in the water over and over again, trying to catch them in mid-air and failing miserably.

The chamaco was breaking the rules in several ways - skipping his laundry duty day, staying out past the time he was allowed to be out, and in a place where he was not supposed to be - but Héctor wasn’t about to give him a lecture now that he had to try and extend the olive branch.

… Oh, who was he kidding, he wouldn’t have given a lecture under any circumstances. He walked up right behind Miguel, grinned, and strummed his guitar with a grito.

“Ayyyyyyy!”

“GAH!”

Miguel jumped a couple of feet up in the air, almost landing in the stream right along with Dante; the only reason why he didn’t was that Héctor reached out to grasp the back of his shirt quickly enough to spare him an unplanned bath.

“Careful, chamaco!” he laughed, pulling him back onto solid ground. “My new song may need a little polishing, but it’s not so bad to jump in the stream over.”

Miguel blinked, taken aback, then grinned. “A new song? What is--” he exclaimed, only to trail off. He made a face, crossing his arms. “I’m still mad at you.”

Héctor sighed. “I know, I know. I’m sorry I didn’t keep my word, Miguel, but it wasn’t a secret I could sit on. I had to make sure Santa Cecilia was not in danger.”

“Ernesto is not dangerous,” Miguel protested, but ay, Héctor would hear the slight hesitation in his voice, notice how quickly he averted his gaze. He frowned.

“Miguel…?”

“I just-- he was really mad that I told you. He yelled at me, hit Dante - I mean, he did growl at him, but…” he bit his lower lip. “He said he should have let me drown the day we met.”

He said what, Héctor thought. I’m going to kick his ass, he thought. With an immense effort, he managed to let neither of those thoughts show.

“He is sorry, and he will apologize,” he said instead. He’d better, or else. “He was under a lot of pressure, and said things he didn’t mean. He-- we were afraid word got out.”

Miguel looked back up at him, alarmed. Héctor, the nuns and everyone else had done their best to shield children from the harsh reality that was the ongoing war outside Santa Cecilia, but any child could tell that would have been bad, bringing the Federales down on Ernesto and Santa Cecilia like wolves on cattle.

“What? But it didn’t, right? It wasn’t me, I told no one else but you, I swear--”

Héctor smiled. “No, it was a false alarm. All is well,” he promised, and strummed the guitar again. “And I have the new song. Want to be the first to hear it, chamaco?”

It had been a while since Héctor had the time to write a new song, even longer since Miguel had been the first to get to hear it, and the thought was clearly enough to chase away the lingering fear and anger. “What is it called?”

“Cómo está tu Padre - it’s about Ernest-- Padre Ernesto and Padre Juan.”

Miguel bit his lower lip. “Padre Ju-- John is not too bad,” he declared.

“Oh?”

“He talked to me. Put in a good word for you when I was mad.”

Well. With how their recent interactions had gone, that was not something Héctor had expected to hear. “Oh. Well then, I suppose I’ll thank him for that.”

“The song isn’t too mean to him, is it?”

Héctor’s smile turned a bit sheepish. “Not excessively. Just some light-hearted fun.”

Miguel seemed thoughtful for a few moments, then he clearly decided it wouldn’t be too bad - or, more likely, that being decent for once was not enough to make up for the huge pain in the neck the gringo had been in the past few days. He perched up on a rock while Dante climbed out of the stream, a rock in his mouth, and flopped in the dirt at Miguel’s feet.

Ah, there was the public. Héctor cleared his throat. “When you're a Man of God, the people come to you to check in on the church…” he spoke, and strummed the guitar before singing.

“As I walk through the plaza,

A señora comes my way

From her lips falls a question

Cómo está tu Padre?

Ay, now what do I say?

The Church of Santa Cecilia

Watches with cynicism

An American man hell-bent on

Sharing blanco egoisms.

Lone, he thinks he's the one!

To have Divine Right to bear down on!

He'll show dismay

When his own way,

Can't stay long.

Such is life, with Padre-”

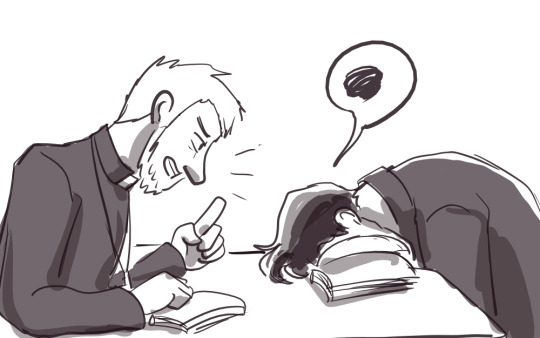

***

“John--!”

“Don’t John me. It’s Father Johnson, and you’ve had your break, Ernest. Now, read aloud--”

“It was three hours ago!”

The protest gained Ernesto a single, insufferable arched eyebrow from the gringo sitting across the table. He had his own Bible open, which looked… significantly more beat up than last time Ernesto had seen it.

“Oh, no,” he said flatly. “Three straight hours of study. No man has ever endured such torment.”

“Well, it is more than enough for me!”

“Unsurprising, considering you seem to be barely literate in Spanish--”

“Hey! I can read, write and do maths, for your information--”

“-- But if you are to learn any Latin before the end of days comes--”

“-- And I can read music sheets! Can you read music sheets?”

The gringo sighed and shook his head. “Not that it is relevant, but as a matter of fact, I received piano lessons as a boy,” he said. His expression, like that of a man who sucked on a lemon, made Ernesto suspect they had not gone too well. “Now, I ask you to focus until at least the end of the page.” He pushed the book back towards Ernesto. “Go ahead, translate the next part.”

Holding back a groan, Ernesto looked back down at the page. If he did what he asked, maybe they would be done soon. “All right, so, uh. Pray for us sinners, which is ora pro nobi--”

“Nobis.” Juan - since using his real name got him no leniency, may as well keep calling him that - cut him off for the eleventh time in the past five minutes. “It is nobis. Which case is that?”

“Uhhh… ab… gen...” Ernesto glanced up, trying to gauge his reaction.

All he got was a raised eyebrow. Again. He was more and more tempted to rip those ridiculous stripes of yellow hair off his face. "Think. Nos, nostri or nostrum, nobis. Nominative, genitive…?"

Something clicked in Ernesto’s head. “Oh! Dative! That would be dative, right?”

An approving nod. “Dative plural, correct. Now, what else did you get wrong?”

Ernesto looked back down at the page, trying not to think that if he’d just let him call the Federales he would now be hanging by the neck from a tree and none of this would be his problem anymore. “Peccatoris?” he guessed.

“Exactly. Peccatoris is genitive singular of peccator, first of all, so at least you didn’t entirely make it up. But in the sentence it refers to nobis, which means it must be…?”

Ernesto gave him a blank look. Juan sighed, but did not lose his nerve. “Think of the same sentence in Spanish - ruega por nosotros pecadores. Why not ‘nostros pecadora’?”

“Because nostros is plural and pecadora is singular. And feminine.”

“And what is the issue there?”

Well, that was a dumb question even a kid could answer. “That it’s got to match.” Ernesto frowned, thinking it over, and-- oh. Oh. “Wait. It’s got to match nobis, so-- dative plural as well?”

A nod, something that almost resembled a smile. “Very well,” Juan conceded, and Ernesto grinned. There, that wasn’t too bad, after a-- “And that would be?”

“Huh?”

“Dative plural of peccator. What is it?”

Ah. “Er… peccatorum?

"That’s genitive."

“Peccatores?”

“Nominative. Or accusative, could be either.”

“Uuuugh.” Ernesto let out a groan, and his head dropped on the desk with a distinct thunk. He could almost hear a smirk in Juan’s voice when he spoke again.

“Peccatores, peccatorum, peccatoribus,” he said, taking a cigarette out of the case. “Ora pro nobis peccatoribus. We’ll go through the third declension again before we call it a night.”

“What-- you said this was the last page!”

“I asked you to focus enough to finish it, didn’t say it’d be the last. You clearly need more prac--”

“It’s almost two in the morning!”

“Then we better be quick.”

Forehead still pressed on the desk, Ernesto groaned. “Don’t you ever sleep?”

“Not without a clear conscience, which is to say not until I’ve done my duty,” Juan replied, and pushed a notebook full of notes in front of Ernesto again. “It’s not difficult. You need to memorize it and, with enough practice, it will come naturally. You should have an edge on me there.”

Was he mocking him? Ernesto raised an eyebrow himself. “... Do I now?”

“Spanish is one of the closest languages to Latin, whereas English has different roots. It was difficult for me to pick up Latin at first. You’re doing quite--” he paused, stopping short of saying ‘well’. “... Passably, for someone entirely ignorant.”

“Hey!” Ernesto protested. He may not be a bookworm, or a scholar, but that was going too far.

“It is not meant as an insult. It comes from Latin ignorare, which simply means ‘not to know’--”

Ernesto dropped his head back on the table, and rather wished the Federal Army would come to put him out of his misery sooner rather than later.

***

“So, we’re marching south?”

“Jesus Christ, we have literally just arrived, I was hoping we could rest…”

“We will, I think they said we’re not going for at least another week--”

“Two weeks. If you’re going to eavesdrop, at least do it properly,” a voice suddenly spoke up, causing the gathered soldiers to wince and turn.

“Commander Hernández!”

“We were just, uh, we--”

“I was not eavesdropping, I only… er… walked by, and… sort of… overheard what they were telling you...”

The newly appointed Commander Santiago Hernández waved a hand, clearly unbothered by the very obvious lie, and they all breathed a little more easily that no punishment would be doled out. That was something they appreciated about Hernández, even though they didn’t know him well: he had been one of them until recently, when his actions in Veracruz and his show of loyalty in refusing discharge had gained him a promotion. He was above them, but didn’t flaunt it nearly as much as others would.

“It will be announced soon, so it is no secret,” he was saying. “Our battalion will remain here for a further week or two, in case reinforcements are needed around Mexico City, but it seems unlikely the current standstill will break. Once we receive the all-clear, we finally head south.”

That word - finally - sounded like a sigh of relief, and the men exchanged a few glances. It was no mystery that Commander Hernández had been itching to lead them down south for a good while, growing increasingly frustrated with the skirmishes and changing tactics that kept them in their current position. He was hellbent on finding a deserter who had shot a friend of his and had fled south, which was understandable but… a touch loco, really.

South is a very vague hint to finding a man who had run off months earlier. This Ernesto de la Cruz may have joined the rebels or been killed by them, died in the desert he’d escaped into, be hiding into some hole or even have crossed the border into Guatemala or British Honduras; chances of running into him were slim to none.

But of course, none of them was foolish to say as much aloud in his presence.

“This will be no stroll in the park,” the Commander was going on. “We will need to get through Zapata’s territory to get there, but it is necessary. We cannot let them push their control all the way to Veracruz and cut the country in two. We will have reinforcements for that part.”

“... And after that?”

“After that, the battalion splits. Some units will go towards Yucatán, while I will lead you towards Oaxaca and then down to Chiapas. There are some very active rebel groups in both regions who support Zapatistas, but few enough they can be dealt with. There is belief they have widespread support among the civilian population, and that is what we need to crush.”

If Commander Hernández noticed any of his men shifting uncomfortably, he pretended not to. His voice was cold, his eyes unyielding, the world reduced to friends to fight alongside with and enemies to be destroyed.

No, not friends - comrades. Santiago Hernández had no friends, not anymore. The last he had left were shot dead, by a deserter and by Americans. His fellow soldiers could show him obedience, show him respect and even camaraderie, but there was no one left to show him friendship.

And no one left who could talk reason into him.

***

“Since he rode in with swagger

And a crass sort of charm,

His unconventional ideas

Keep our town safe from harm

He draws in crowds

To the church, old and young

Quick to bestow,

He'll make his blessings come

We were fatherless, and

Hey, presto!

We were gifted with Padre-”

“Miguel.”

“-- Huh? No, Ernest-- gah!” Miguel let out a yelp, trying with very little success to hide the guitar behind his back and acutely aware of the fact the small crowd of children who’d been listening to him was dispersing very quickly; out of the corner of the eye, he could see Óscar and Felipe leaping over a fence like thoroughbred horses. Within moments the only ones in the yard were himself and Dante, with Father John towering over them.

… Well, at least he didn’t look too mad. Only rather tired. Miguel was suddenly very glad he’d decided to only sing the part about Ernesto and not the bit about him. Even so, seeing children shrieking and running off when he approached probably was… not very nice. Miguel gave a smile he hoped would come across as charming but that was actually very, very sheepish.

“Hola, Father John,” he said, making sure to pronounce his name as correctly as he could. The priest’s thin lips curled for a moment in something reasonably close to a smile.

“Hola, Miguel. That was… an interesting song.”

“It was just… just a bit of fun.” Miguel shifted a little, hoping he wouldn’t find out about the rest of it, or who had written it. Thankfully, the gingo didn’t prod for more details.

“... I do apologize. It was not my intention to spoil your fun. I am searching for my Bible - I seem to have lost it,” Father John said, letting his gaze wander around the yard, on the low stone wall and the few benches - but there was no sign of a Bible anywhere. “It is quite old and ruined, but it has a sentimental value. Could you spread the word and let me know if you find it?”

Ah. “Of course. I can go look for it. I will now,” Miguel spoke quickly, and turned to leave - but Father John spoke first, causing him to pause.

“... You do miss Father Ernest, I gather,” he said, and well… there was no point in lying there. Ernesto had even apologized to him for snapping, as Héctor said he would, even though he’d offered no explanation, and Miguel had accepted the apology. So all was well now… right?

“We kinda miss him at Mass,” he admitted. “I know you said he’s busy with other things, and-- I like how you say Mass,” Miguel added quickly, hoping he had not noticed how he’d almost dozed off and dropped the incense the previous Sunday. “It’s just-- well-- you know--”

“It’s all right, I understand. I’ll ask him to say Mass this Sunday,” he said calmly, and walked back to the church. As he watched him go, more of Héctor’s song echoed in Miguel’s head.

Like oil and water

Their teamwork does seem strained

And so I often am questioned

Cómo está tu Padre?

***

Father John Johnson lit his next cigarette against his best judgment.

He normally practiced more restraint, even with a vice, especially considering rolling papers and tobacco felt like something immoral to spend his small allowance on in such hard times. That, and it was the last in his tin - which meant that in order to get more he’d have to go on an unpleasant trek up the hill, to the small stand on the edge of town, with the little gruff man who clearly overcharged and quipped about John reminding him of Spaniard colonizers each time.

John’s family was actually of Dutch ancestry - not a drop of Spanish blood as far as he was aware - but it was a fight John had decided not to pick. He’d just take the scathing remark and be content that the man wouldn’t go telling the rest of the town that the gringo priest bought tobacco from him. By far not his most shameful secret, but still one he’d tried to keep hidden.

“And what’s the point of that anymore,” John mused aloud, leaning back against a tree.

As much as he’d tried to avoid the thought, he feared his worse sin would leak to this town sooner or later, due to Ernest’s continued existence here. Granted, the man had all the more reason to keep John’s secret now that his own had been found out, but a slip of the tongue was all it would take.

And if that happened, well, he would no longer have to worry about keeping his smoking habit hidden. Who’d be bothered by a priest having a penchant for foul-smelling habits when it’s common knowledge he has an even stronger penchant for men in his bed? Perhaps Brother Hector would write a song about that, too. The thought terrified him, knotting up his stomach, and yet he couldn’t hold back a bitter laugh before he took another drag.

Such thoughts circling endlessly in his mind were part of the reason for his irresponsible rationing of cigarettes, along with Ernest’s gauche behavior ever since he showed divine and priestly mercy.

That morning’s breakfast had made him nearly reconsider indulging Sister Sophie’s plea for Ernest’s pitiful life. The man had been edging toward familiarity ever since John had given him the gift of mercy allowing him to remain in the parish, so long as he did his best to behave like a real priest so no one else learned his secret - which meant listening when John assigned him scripture to study, so his sermons no longer consisted of him improvising stories he thought he remembered from childhood.

Even so, he regretted allowing Ernest to occasionally say mass to keep people from questioning the change. It took all the restraint in John’s body not to stand up in the middle of mass that day to correct him that Jesus never ‘set a temple on fire for revenge’ and certainly did not ‘condone’ arson in the ‘right situation’. Indeed, John 2:14 was his first assignment for that little mishap.

Clearly, the lesson Ernest had taken from it was not precisely the one John had hoped he would. Instead he seemed quite coy at breakfast declaring loudly to all the sisters and impressionable Hector how reexamining the bible was such a ‘good reminder’ that Jesus simply ‘doesn’t care much if we sin!’.

“He was a bit of a hell-raiser himself! A rebel!”

Each phrase announced with a strongly targeted grin toward John in an obvious attempt to excuse his own behavior, which nearly caused John to flip a table himself. But he had shown restraint, and channeled that anger into what was now his last cigarette, which he would attempt to savor as slowly as possible.

“There you are!”

The voice burst seemingly from nowhere, causing him to yelp. “Lord have mercy!”

John startled, nearly dropping the cigarette and turning to glare up at that man. In response, he just grinned.

“I thought you had better reflexes than that,” Ernest began, the forced friendliness and warmth radiating off him just as strongly as it had during breakfast. He either wanted something from him, perhaps more foul carnal acts - in which case he would be sorely disappointed - or was trying to make sure his little stunt that morning hadn’t cost him John’s silence and mercy.

John inhaled, his voice coming out strained with fragile control. “I have… given you respite, patience, and lessons. I can not fathom a reason you must accost me in private when I have been explicit that unless it is in the parish for lessons we are not to--”

Ernest didn’t seem to be listening: the next moment he was plopping into the grass beside him, leaning on another side of the tree. “I know, I know,” he said with a dismissive wave of his hand. “I’m not going to take up much time, it’s just that you rather rudely ran off at breakfast--”

“You cannot fathom how close I was to strangling you over the nonsense you were spouting, you should count yourself lucky that I left--”

“But,” Ernest cut him off, “you left before I made my point about my, uh, study of scriptures.”

“I’m not grading you,” John replied flatly.

“I am aware. But I think I found something that could bring you, uh…” a vague gesture. “I just think it’d be something you’d like. I don’t think what you-- we are is such a big deal. In case you missed it--”

Missed it - now that was nothing short of an insult, and John’s composure broke. “I’m the real priest, Ermest - what could you possibly teach me that I don’t know about scripture!” he barked. Ernest didn’t even flinch, but lifted a Bible he’d seemingly pulled out of nowhere. Had he kept it hidden under his robes for a dramatic reveal just now?

“What, don’t like to think I can get something you didn’t?” Ernest made a face. “I am pretty smart, if I say so myself. Even you admitted I’m getting the hang of Latin.”

His boldness was coming back each day he awoke to see John had not yet cast him out it seemed. “Pride is a sin,” John muttered, making an effort not to release a slew of profanity he would have to confess to - God knew who to, since he was the only priest in the village. Instead, he pressed the cigarette between his lips and inhaled as though the smoke was oxygen.

Ernest shrugged. “Anyway. I’ll have you know that according to Romans 3:23--”

“Yes, yes. ‘For all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God’,” John replied without missing a beat. “I’m well aware. Is this a case to prove why you deserve full forgiveness and a return to--”

“Well, if you shut your mouth and let me finish, maybe you’ll see.”

Oh, John would love to be a pettier man, to make some empty threat about changing his mind to get Ernest on his toes again. But, well… God was watching, and he’s sinned enough lately. Far more than enough.

“Well then,” Ernest was going on. “Since he’s saying we’re all sinners, there’s no reason to feel particularly bad if we--”

“Priest. I’m a priest,” John cut him off again, stressing the words just enough to remind Ernest that he was not one, regardless of the cloth he wore.

“Huh?” He seemed honestly confused. “I know you’re--”

“Do you just keep forgetting priests are on another level of standard than--”

“Cálmese one minute, will you?”

“I am calm!” John snapped. “But if you don’t cease blaspheming, I’ll have you study so much--”

“So anyway,” Ernest barreled on before he could be scolded for the disrespect. “That verse reminded me of one I heard as a boy, and it took some digging to find it, has anyone ever thought of alphabetizing this thing?”

“This thing would be the Holy Bible, it would be appreciated if you showed some respect towards the Word of--”

“Anyway, it was a Psalm,” Ernest continued, clearly having made a habit of not acknowledging John’s attempts at educating him that day. “And it went, ‘for you created my inmost being; you knit me together in my mother’s womb. I praise you because I am fearfully and wonderfully made - your works are wonderful’, and so on, right? God made us and all that, and makes no mistakes. You told me - and I’ve watched - you tried everything to avoid these desires, so… why would God make a mistake with you?”

John was silent for a moment; it mirrored a touch too closely to the argument Father Joseph had given him years ago. Shaking off the alarm, he turned his gaze on Ernest’s face for the first time in the conversation. “You have mistaken the Devil’s influence for divine design.”

“Didn’t you tell me you’d felt this way since you were a child - an innocent?”

“I was not that young, I was…” Almost a man, he’d thought then, but looking back now… oh, he truly had been barely more than a child. Something ached in John’s chest and throat, and he swallowed before speaking. “The devil, he… he works in deceitful ways.”

“Me too, you know.”

John scoffed. “Yes, you certainly do work in deceitful ways too, but that is no reason--”

“No, I mean-- being like that. As a boy.”

Ah. John fell silent, and turned back to Ernest. His hands were crossed, and he looked… uncharacteristically uneasy, no longer looking at him. “Even before my… experiences in, uh…” a sigh. “I said it was seminary, but of course that was not it.”

“Where…?”

“In the army. Overall unpleasant.” A bitter chuckle, but he didn’t elaborate. “But well before then, I would look at men. Other boys, really, well before I knew what sodomy was. Like you, correct?”

John had only ever looked that way at one boy when so young, but the memory of Walker Underwood - leaning back on the grass beside him to look up at the stars, talking and laughing, so unaware of John’s reddening skin and uneasy thoughts - still hurt all those years later, and he chose not to remark on that.

“... Correct,” he murmured instead, and Ernest nodded before speaking again.

“And it was not lust exactly, was it? Too young for that. So… why’d God make you like that if his design is divine? Either of us?”

A somewhat smug smirk was emerging on Ernest’s face, like that of a pupil who had turned in an immaculate report despite the teacher’s mediocre expectations. John turned his attention to the grass, his smoking hand lingering in the air as Father Joseph’s kindly voice and words echoed in his head.

Perhaps it is in God’s plan that it remains your cross to bear.

Ah, but Ernest did not think of it as a cross to bear. He accepted it, embraced, revelled in it… and God had not struck him down for it. He’d struck down neither of them.

He was quiet so long that Ernest’s look of confidence began to waver, as though he feared that perhaps he had simply broken him further as opposed to-- ah, was comforting him what he’d meant to do? His way to apologize for his deception? John suspected as much.

The thought sat warmly in his chest, and that feeling in itself should have concerned him, but… he wanted to revel in what comfort that knowledge gave him, if only for a little while.

Without a word, slowly, John’s free hand landed on the one Ernest rested in the grass. A delicate pat, the kind of gratitude a widowed parent shows to the child who thinks they can console them with a false belief the dead will return, knowing full well it is not to be. But the key there was that he... he recognized the attempt.

“You’re dreadfully naive about scripture theory.” John remarked, his voice somber. Before he could pull his hand free Ernest took hold of his index finger, forcing him to linger.

“Either I’m right, or God has messed up a lot of kids in his design.”

The notion God may mess up in any way, shape or form was another blasphemy, but it was probably the point Ernest was clumsily trying to make. So John didn’t rebuke him, nor did he try to pull away from his grasp, which was loose enough for him to be able to do so effortlessly. There was a doubt that may be just a ploy from Ernest’s part to remain in his good graces, or maybe even slither back into his bed, but even so it was difficult not to appreciate the gesture.

Perhaps he means it. Father Joseph surely did.

John gave a single nod, and allowed his hand to be clasped as he finished the remainder of the cigarette - Ernest’s presence no longer quite as stressful as it was before. Then the cigarette was done, he blew out the last of the smoke, and he pulled his hand away.

“We ought to head back--”

“Here,” Ernest said suddenly, pushing the Bible in his hands. John blinked, taken aback, and glanced at him to see he was looking away. What in the world…?

“You know I can quote the Bible in my sleep, don’t you?” he pointed out, just a little offended. “I know exactly which passages you’re quoting. I simply don’t think your simplistic interpretation--”

“No, I mean--” Ernest fidgeted, uncharacteristically uneasy with words. “That’s yours.”

“... I beg your pardon?”

“Your Bible. I, uh, got someone to fix it up. As a, you know. Apology.”

Ah. John looked down at the Bible in his hands, truly focusing on it for the first time. That wasn’t his Bible, it couldn’t be; he’d ruined it slamming it down on the camera, until the spine broke, the leather cover came off and several pages came loose. The one he held in his hands was newly bound, now, with a new cover and all pages firmly in place. Still, when he opened… that was his handwriting at the margin, his notes. His Bible, indeed. So that was where it’d gone.

“I see,” John heard himself saying, his throat a little tighter. He instinctively flipped the pages, searching for-- yes, there it was, right where he’d left it: his father’s letter. Disowning him, telling him he no longer had a son, to never be in touch again, so he wouldn’t taint them. But for the first time, seeing that letter did not fill him with shame. It filled him with anger.

“Didn’t you tell me you’d felt this way since you were a child - an innocent?”

I did nothing. I was a boy, I only thought of kissing another. His own child, cast out over nothing.

“I noticed it looked kind of ruined, and I figured old Raúl could fix it up,” Ernest was saying, seemingly unaware of his thoughts. “He owed me a favor, so--”

“Thank you,” John said, very quietly, and smiled, the restored Bible - his keepsake of Father Joseph, the man who had called him his son despite everything - clutched to his chest. “This means more to me than you’ll ever know. I-- I have no words.”

Ernest smiled back. “Not even in Latin?” he asked.

And, for the first time since the truth had become clear to him, John Johnson laughed.

***

Well, getting Juan’s Bible fixed up hadn’t saved Ernesto from his daily Latin lesson, but at least he’d been allowed to go to sleep at a reasonable enough time, so there was that.

Not that he had hoped to fall asleep soon or easily, because he never did, not when he had to sleep alone. In the dark and the silence, falling asleep to find himself back in the barracks - or in a battlefield, or marching under the sun, or about to gun down civilians - was all too easy. So far, he found that some company was the easiest way to keep all of that away at night.

He’d tried to casually suggest Sofía to spend the night with him, but of course, she’d shrugged him off and said she had plans. She was probably living it up with Sister Antonia right now, who was pretty but, in Ernesto’s opinion, nothing to write home about. Unlike him, of course. He was very much something to write home about. Or to the Archdiocese. Thanks for that, Juan.

Ah, yes. Juan. Asking him for nightly company was now entirely out of the question for obvious reasons, but Ernesto found that the thought of him helped a little just now. Namely, the thought of the look on his face when presented with his fixed-up Bible; the surprise, the smile, the laugh. It had been… nice, to hear that laugh again.

Not that it had been the goal, Ernesto thought, but he was not entirely sure what the goal had actually been. He’d just eyed Juan’s Bible on the table after the gringo left to deal with some confessions, and thought that it looked in terrible shape, like he’d dropped it from a great height. He vaguely remembered Juan telling him that the old Bible was a gift from Father Joseph and very dear to him, much like the crucifix around his neck.

Grabbing it had taken a moment, and the walk to Raúl’s shop only minutes. The man was mostly a leatherworker, but was good at book binding and also the father of a woman finally expecting a child after years of fruitless marriage thanks to Ernesto’s, er, blessing - so he owed him a favor. When he’d returned to pick it up, the Bible looked new and he’d actually flipped through it to check Juan’s notes and make sure it was the same one he had left.

What am I doing?, he’d asked himself then, and he did again now. ‘Getting a book fixed’ was technically the right answer, but why would he bother was another matter entirely. He told himself it was vital he remained on the gringo’s good side, and that also was technically true. So there, that had been it - no motive but self-preservation, as always. End of story.

Ernesto turned to the wall, pulled the covers up to his chin, and closed his eyes. His thoughts did keep drifting back to Juan’s smile, which was annoying, but when he finally fell asleep no soldiers, screams or gunfire disturbed his dreams. All in all, it could be worse.

***

You no longer have a father. I only ever had one son. For both of our sakes, never write again.

For a long time, John stared in silence at Reverend David Johnson’s neat handwriting in the flickering light of the candle barely lighting up his room. He had read that letter every morning upon awakening, and every night upon going to sleep, for well over a decade. A reminder of his sin, of his failure as a son. It hurt, each time, and it hurt him now.

Only that the hurt was different that night, the disdain no longer entirely against himself. The letter was written on Christmas Eve, a brief unfeeling response to a heartfelt plea. Cold. Cruel.

I was a child. I was his child. How could he?

John pressed his lips together, the letter in one hand and his Bible in the other. A father’s rejection, ink more and more faded, and a Father’s gift - now restored. John’s eyes drifted towards the candle and, while he did not burn the letter, he did think about it.

He thought about it for a very long time.

***

“A flying machine! What in God’s name were you two thinking??”

“That we wanted to build a flying machine. It worked pretty well, except for the part where it didn’t fly.”

It took every ounce of Imelda’s patience, plus some she probably borrowed directly from the Almighty, not to grab Felipe by the front of his shirt and shake him hard enough to make his teeth chatter - and if not for the fact he had a broken left arm in a cast, she may not have been able to hold back.

“Maybe we should have picked someplace less high for the first test,” Óscar was conceding, all bruises and skinned elbows but with his bones still all in one piece. “We’ll choose better next time.”

“Next-- there is absolutely not going to be a next time.”

“Yes, yes, that’s what mamá said.”

“Papá as well.”

“So we knew you’d say that, too.”

“But you need not worry, because the next flying machine will actually fly!”

Imelda groaned, reaching up to rub her temples. “Was a broken arm not enough for you?”

“Nope! I still have the other one,” Felipe quipped, flexing the arm in question to show off absolutely non-existent muscle.

Óscar laughed. “And on the bright side, if the Federal Army comes looking for new soldiers, they won’t take him! Huh, maybe I should break my own arm--”

“Don’t say that,” Imelda cut him off, her voice suddenly sharp. It was the sort of thing she’d been having nightmares about. “Not even as a joke.”

“... The arm thing or the army thing?”

“The Federales. Actually, both. But mostly the Federales.” Imelda found she couldn’t entertain the thought even for a moment and something had to show on her face, because both of her brothers stopped smiling at exactly the same moment.

“Hey, we… we didn’t really mean it.”

“We won’t say that again. Promise.”

Imelda sighed and finally nodded, managing a smile. “... Good. And if you want to entirely reassure me, you may also promise you will not keep trying to build flying contraptions and launch yourselves--”

“Oh look, it’s getting late!”

“We should be home in five minutes!”

“We should have been home five minutes ago!”

“Wait a moment--” Imelda began, only to trail off when her brothers took off running in the direction of their home. She sighed, making a mental note to let her mother and father know they should keep all tools under lock and key next time she saw them. Not that she thought it would stop them, but at least it would slow them down. Possibly until Felipe’s arm healed.

Their joke about Federales passing by to pick men to replenish their ranks rang through her mind as she walked back towards the parish, impossible to entirely ignore.

If they took them, I don’t know what I’d do.

Her thoughts turned for a brief moment to the loaded pistol she kept hidden in her room. She paused mid-step, clenching her jaw. No, that wasn’t entirely true, was it?

She knew exactly what she’d do.

***

“He left, didn’t he?”

“Yes, Commander, as you said he would. We watched him take a horse and ride off.”

“Of course. To warn his friends down south of what he heard in the cantina, no doubt.”

Santiago took a swig of his drink before setting down the glass, eyes glued to the map. It had been a grueling business, pushing past Zapata’s forces immediately south of Mexico City, but they had made it and now the battalion had split, leaving him in command of a couple of units… heading for the area where Ernesto de la Cruz had fled, leaving behind Alberto’s body in the smoldering sand.

I’m getting closer, I know I am. It’s only a matter of time.

And he could wait, of course. He could bid his time; being in the army had taught him discipline… something many of his men severely lacked. They were unruly, prone to talk and drink and then to talk even more after a drink… and that small village was full of ears. Thank God, said ears were also very bad at spying without being entirely too obvious.

Sergeant García scowled. “Do you want us to follow him and take him out before he can warn them of our itinerary?”

“No, let him warn them. Let those traitors waste time rallying around San Luz while we take another route right past them.” With some luck, they may even be able to catch them by surprise from behind. He’d come up with another itinerary, and avoid sharing it with anyone who didn’t strictly need to hear it.

“I see. Do you need any further help…?”

“I think I’ll be fine, thank you. You’re dismissed.”

The sergeant left and Santiago focused on the map again, slowly working his way through the glass. There were several alternative routes they could take, but he settled for one that went through some hills and a small village barely marked on the map, the name printed in such tiny letters he had to squint to read it.

Santa Cecilia.

***

A/N: yes, I had to study Latin and had nightmares about it from time to time. But it's cool, they're fading.

Ancient Greek, on the other hand, shall haunt me to my grave.

***

[Back]

[Next]

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

weird opinion but christians aren't religious.

ok so like, jews generally follow god's rules, muslims follow allah's rules, hindus probably follow their gods rules, so on and so forth. and overall they do it out of faith; they do it because they want to honor the deity who loves them rather than because society forces them to.

granted the zionists and the radical extremists and the zealots do exist but as loud minorities and thus are statistical outliers & don't matter.

christians are... a different breed.

"if you aren't x branch and dont obey y rules you'll go to hell so we'll fucking murder you" is pretty much the main driving force behind a significant portion of christianity in history. the catholics, the protestants, the orthodoxy, all are built on a foundation of fear, anger, and hatred. it's shaped the way society developed; in the 4 nations that did the most genocidal imperialist colonialism- England, France, Spain, and Italy- a combination of convenient coastal locations, naval prowess, military tendency, christianity, and ultranationalism lead them down a path of missionaries, holding bibles in one hand and bloodstained knives in the other. the religion is inseparable from the culture and inseparable from the horrible things done in the name of their god, and the resulting cancers of society we feel today from the campaigns of slaughter. xenophobia. capitalism. savage barbarism via sensationalized capitol punishment. misogyny. queerphobia. gender fascism. classism. racism. all of these issues in the "civilized world" stem predominantly from those four nations and the disease ridden pestilent filth some call pilgrims.

here's something interesting:

there are less than 1 million rastafari in the world.

there are less than 5 million shinto in the world.

there are less than 25 million jews in the world.

there are less than 30 million sikhs in the world.

there are roughly 100 million african cultural religious adherents in the world.

there are less than 400 million chinese cultural religious adherents in the world.

there are about 500 million buddhists in the world.

there are about 1.1 billion hindus in the world.

there are about 1.2 billion nonreligious people in the world.

there are 1.6 billion muslims in the world.

and one final statistic

there are over 2.1 billion christians in the world.

the jewish count is a highball, rounded up, and includes several different definitions of jewish including people who are only one quarter. so for every single person who is even remotely jewish, there are more than 8 christians. for every hindu, there are 4 christians. for every atheist, agnostic, or "other", 2 christians. this frightening statistic should set off warning bells for everyone who is involved in a discussion about religion. and anyone who knows BASIC world history and can correlate data at all can probably piece together what I'm putting down.

now, I may be slightly biased here considering my eclectic religious beliefs. now, I personally believe that there is some primary force of energy that may or may not manifest itself as a humanoid being, that engineered the most basic laws of physics in the universe: atomic magnetism. as can be inferred by planck's constant and its implications, our universe is digital, written in binary. an electron either moves or doesn't move. there are no other options. so I genuinely believe in some form of intelligent design; whether it's a bearded guy on a cloud, some dude with six arms and an elephant for a face, just a big swirling pool of ectoplasm, or a big ol' plate of spaghetti and meatballs, something is out there that we are physically incapable of contacting from our plane of existence, just as a drawing on a piece of paper cannot reach out to interact with the world: a gif will move on its own but it will never acknowledge our existence, even if it could think by itself. and all the different mythologies of the world- egyptian, greek, norse, shinto, whatever- very well could be the agents of that unknown "god". perhaps anubis, ra, and bastet are just angels with animal heads that all of the peoples of ancient egypt saw and were like oh I guess this must be a god. maybe zeus and loki were the same person with a magic dick who fucked a bunch of animals in both greece and the scandinavian countries and spawned all of the horrible half-animal monstrosities that, idk, made vishnu think "well I have to kill that" and caused the biblical flood or something. maybe the jewish god gifted wisdom to siddhartha for sitting under a fig tree for 6 years through the angel pomona [roman goddess of fruit, had to google that one], so buddha gets his wisdom from demeter and is in nirvana right now right a step up from hades on yggdrasil the world tree keeping an eye on his charge persephone. any theory could theoretically be true but we ants of humans will never fucking know because we can't just point a telescope at the magellanic clouds and say "look, there's amaterasu with russell's teapot, and she's having tea with... *rubs eyes* lemmy kilmister??? wow I guess gods are real after all!" it's impossible to know the secrets of our universe because of the very restrictive nature of the universe itself. is it a circle? is it a donut? WE DONT FUCKIN KNOW.

we cannot know what religion is truthful.

""anyone who says that any one religion is more or less true than any other is a fucking moron, and if they're suggesting that White Western European Colonial Imperialist Protestantism is the one true faith, they're probably a fucking racist colonizer who beats his wife/sister and burns gays at the stake. and considering how that exact demographic is typically the one that murdered people for not converting to their religion, I don't think they have the intellectual non-deranged ability to make those logical connections.

again, I'm not saying that there AREN'T a lot of people of every religion who are evil assholes who contributed to mass genocide. israelites killed palestinians. shiites killed sunnis. hutus killed tutsis. danes killed geats. turks killed armenians. the ottoman empire has as much blood on its hands as the holy roman empire. germans who called themselves aryans but weren't actually aryan killed jews. but all of these tragedies were isolated incidents rather than repeated patterns over the course of two thousand years. not like christianity was and is.

just look at the United States, Canada, Mexico, Hong Kong, South Africa, Australia, & India's British Raj. Britain, France, Spain, and Italy, by extension Protestantism and Catholicism, are the shared factor between the long and bloody history fraught with massacring indigenous populations who wouldn't convert religions. native americans, indigenous canadians, latin americans but predominantly mexicans, the eastern chinese, coastal africans, aborigine aussies, indians- coastal coastal coastal. true the western chinese and the mongols/hunnu and xinjiang muslims haven't exactly been on civil terms and the silk road has always been a battleground and the middle east was already tenuous before murrica bombed them for oil but those happened in such a spread out area among asia which is FUCKING HUGE, MIND YOU! but also that's three high traffic places with massive diversity, it's human nature to have conflict, but not nearly to the same level as all of the shit christianity has done to the world. it's impossible to separate the religion from the cultures; victorian england without protestantism is just dirty people who die at 15 from having their 3rd child. italy without the catholicism is just grass and cheese. france and spain without religion are just kingdoms that fought wars with england for forever and now just make food that's one part delicious and three parts horrifying. religion is directly responsible for a significant portion of the evils those countries committed. one religion in particular.

they don't practice religion the same way as the rest do. they aren't faithful to their god. they don't follow his rules out of love but out of fear. they execute dissenters without a second thought, heresy they cry. they execute women and little girls for being free thinking or having sickness associated with mercury poisoning in the water, witch they cry. they slaughter men women and kids alike in the name of cramming their beliefs down the natives throats, we're chasing out the snakes they cry, we're bringing god to your godless people they cry, we're just civilizing you they cry. they shit in the streets and proudly display rotting corpses and leave the impoverished disabled and starving to die alone and whip their slaves and rape teenage girls and scrap in the streets while sopping wet with spilled ale over insignificant insults and stab people to death in the night and never even fucking BATHE, and they have the nerve to say the natives were uncivilized. the nerve. because hey. they read a magic book they stole from a culture who stole from another culture who stole from another culture, mistranslating each time from hebrew to greek to italian to english, and they think they're better because their skin is white.

christians never evolved. their mentalities have stayed the same. all thatms advanced has been technology. that's it. they're still the same evil disgusting degenerate bastards they always were. they just have the money they stole to buy stained glass windows, rosary beads, giant tacky metal statues, bigass robes, leather, and printing presses. and as time passed they used the money they continued to steal to buy cars and websites and radio stations and commit felony tax evasion and secretly molest children and line the pockets of the politicians.

all of their holidays are stolen from pagans anyway.

so fuck christmas. fuck easter. fuck lent. fuck the golden calf christian holidays that the tiny minded fragile snowflake conservatives lose their collective shit over because the pandemic response common sense stipulations won't let them buy the shit they can't afford with money they shouldn't have for people they don't even LIKE, all in the name of tradition, tradition! the rituals that worship something so much worse than satan or baphomet or pan or whatever: the dollar. they buy all the new shiny shit they can, at the expense of the chinese kids that the corporate pigs outsource to, buy the pine trees and the coca cola vunderbar and the fake mint corn syrup Js and watch the same shitty cookie cutter white supremacist hallmark fash movies and stuff their kids full of enough sugar to go into a goddamn coma when the african slaves who pick the cocoa beans will never get to know what actually being a kid will ever feel like because they're gonna die from falling into a combine harvester and be eternally forgotten to history and no christian will ever give a shit because they don't fucking care about what they don't see on their safe space news or hear on their safe space radio or read on their safe space social media. they think their worst sin is eating cheeseburgers so instead they'll go eat a mcchicken or chick fil a or an arby's chicken sandwich instead but not at popeyes because "that place is sketchy" and by that they mean they don't wanna eat where black people eat, that's why cracker barrel was so popular for so many white christians for so long because it had racially segregated seating until barely 20 years ago.

they don't love jesus. they love a paper doll they shove into their back pockets until every other sunday where they go to a fucking mall with a baptism waterslide and raise their hands like a bunch of dumbass weirdos and away to adult contemporary indie schlock with the word jesus pasted into a boring-ass hetero romance song, pat themselves on the back, then go to starbucks to scream slurs and misgenderings at 14 year old starbucks baristas who give them a cappamochalattechino instead of a fucking carmamochalattechino because you mumbled under the mask you didn't even fucking cover your nose with because you don't give a shit about the virus beyond how it inconveniences you.

they are horrible people who pretend to be good. until you suggest the slightest infinitely small inconvenience to them that would alter their holiday plans even the littlest smidge. then they would kill you if not for the police. don't get me started on them because you know by now what I'd say about those fuckers. but they'll gladly wear shirts about how they'll kill you. how they'll go back 200 years. how they'll murder you and watch you slowly suffer because their primate brains shoot a million endorphins when they watch things die by their hands because they never evolved a sense of empathy, compassion, or morality beyond how wearing a cross necklace will remove any of the consequences they will face in their afterlife.

they are horrible people who pretend to be good. unless you're gay or black or trans or Not Christian™ or mexican or disagree with them about politics economics sociology science technology music or movies. assimilate or die. assimilate or die. assimilate or die.

they don't deserve special treatment for their false idols.

they aren't better than jews or muslims.

they're worse.

so much worse.

and they should be stopped.""

-Nightingale Quietioca

save as draft arch draft bookmark draft where did I put my keys contra code kontra kode I need to remember this and copy it buzzwords keywords find it later please god tumblr don't bork on me this is good stream of consciousness repackage repackage change the words this is a great character study if I do say so myself thanks 3am me you're welcome 3am me

21 notes

·

View notes

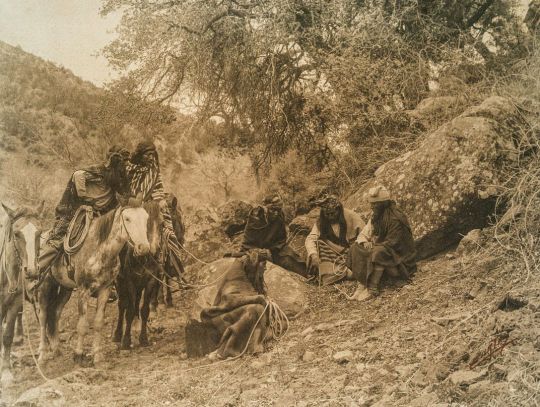

Photo

Day 2 — God Bless America

God Bless America’s lyrics have a storied history — one deeply entwined with America’s ever-uneasy relationship between religion and politics.

The song was written by an immigrant. Irving Berlin arrived in New York at 5 as Israel Baline, the son of a cantor fleeing persecution of the Jews of Russia. During World War I, Berlin wrote “God Bless America.” The title was a phrase his immigrant mother fervently repeated during Berlin’s childhood, his daughter later said.

When the song finally debuted 20 years later, the backlash began almost immediately. A Jewish immigrant, critics said, should not get to celebrate this country as his. (Not to mention celebrating Christian holidays: Berlin wrote “White Christmas” and “Easter Parade,” among his massive catalogue of popular hits.)

In the newsletter of an American pro-Nazi organization, one writer expressed this vehement attitude in 1940: “[I do] not consider G-B-A a ‘patriotic’ song, in the sense of expressing the real American attitude toward his country, but consider that it smacks of the ‘How glad I am’ attitude of the refugee horde of which Theodore Roosevelt said, ‘We wish no further additions to the persons whose affection for this country is merely a species of pawnbroker patriotism — whose coming here represents nothing but the purpose to change one feeding trough for another feeding trough.'”

Others rejected Berlin’s optimistic theology in a song he himself called a prayer. Woody Guthrie began writing “This Land Is Your Land” as a parody criticizing “God Bless America” for overlooking America’s flaws. Guthrie’s original title for his song was “God Blessed America for Me.” One of the lesser-known verses of his now-famous folk song goes: “One bright sunny morning, in the shadow of the steeple | By the Relief Office, I saw my people. | As they stood hungry, I stood there wondering | If God blessed America for me.”

As America’s entrance into World War II drew nearer, the country embraced Berlin’s song. It was played at both the Democratic and Republican conventions in 1940, and every Brooklyn Dodgers game that year.

The song became an anthem of an array of causes. Striking garment workers and protesting subway workers sang “God Bless America” in the 1940s and ’50s. Students protesting racial segregation in Louisiana and Mississippi in the 1960s sang it. The antiabortion movement adopted the song in the 1980s.

By the 1970s, the widely employed “God Bless America” was taking on a conservative association that it retains to this day. Sheryl Kaskowitz writes in her book “God Bless America: The Surprising History of an Iconic Song,” that the deep social division over the Vietnam War marked a turning point for Berlin’s melody.

“The song became a staple at pro-war rallies, and was often used as a sonic weapon in conflicts with anti-war protesters,” she writes. “If conservatives can be understood as revolutionaries reacting against the progressive social change movements of the 1960s, then “God Bless America” was their “We Shall Overcome,” used by activists expressing opposition to progressive social movements like school integration, women’s rights, and abortion.”

President Richard M. Nixon, who represented those conservatives rejecting social movements of the 1960s, frequently referenced the song and even sang it at a state dinner alongside Berlin himself, who died at 101 in 1989. President Ronald Reagan, the first embraced by the new religious right, did not just play the religious-patriotic song at his rallies. In his prior career as an actor, he starred in the 1943 movie “This Is the Army,” which was the first film to feature the song.

Others who have embraced and popularized the song continue to include, like Berlin, immigrants and admirers of this country who were not born in America. Among the most memorable renditions of the song in recent decades was Celine Dion’s version, recorded for a fundraiser album that hit No. 1 on the Billboard chart after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks. Although she is Canadian, Dion sings a soulful “God Bless America.”

When Hispanic singer Marc Anthony performed the song at the 2013 baseball All-Star Game, racists attacked his performance, tweeting slurs including, “C’mon MLB. How you gonna pick a Mexican to sing ‘God Bless America’?” and much more. Anthony is Puerto Rican — meaning he is American.

In other words, a century after the song was written, we are still fighting about who is entitled to proclaim blessings upon the “land that I love,” and “my home sweet home.” Berlin might answer: anyone who knows the words.

— From The surprising history of “God Bless America,” the patriotic hymn Trump might have forgotten, by Julie Zauzmer, Washington Post, 6 June 2018.

Photo: Graffitied wall, Brooklyn, NY

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The United States vs. Billie Holiday: The Federal Bureau of Narcotics Was Formed to Kill Jazz

https://ift.tt/3smcRhE

This article contains The United States vs. Billie Holiday spoilers.

Federal drug enforcement was created for the express purpose of persecuting Billie Holiday. Director Lee Daniels’ The United States vs. Billie Holiday focuses a cinematic microscope on the events, but a much larger picture is visible just outside the lens. Holiday’s best friend and one-time manager Maely Dufty told mourners at the funeral that Billie was murdered by a conspiracy orchestrated by the narcotics police, according to Chasing the Scream: The First and Last Days of the War on Drugs by Johann Hari. The book also said Harry Anslinger, head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, was a particularly virulent racist who hounded “Lady Day” throughout the 1940s and drove her to her death in the 1950s.

This is corroborated in Billie, a 2020 BBC documentary directed by James Erskine, and Alexander Cockburn’s book Whiteout: The CIA, Drugs, and the Press, which also claims Anslinger hated jazz music, which he believed brought the white race down to the level of African descendants through the corrupting influence of jungle rhythms. He also believed marijuana was the devil’s weed and transformed the post-Prohibition fight against alcohol into a war on drugs. The first line of battle was against the musicians who partook.

“Marijuana is taken by… musicians,” Anslinger testified to Congress prior to the vote on the 1937 Marijuana Tax Act. “And I’m not speaking about good musicians, but the jazz type.” The LaGuardia Committee, appointed in 1939 by one of the Act’s strongest opponents, New York City Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia, ultimately refuted every point made in the effective drug czar’s testimony. Based on the findings, “the Treasury Department told Anslinger he was wasting his time,” according to Chasing the Scream. The opportunistic department head “scaled down his focus until it settled like a laser on one single target.”

Federal authorization of selective enforcement should come as no surprise. Just this month, HBO Max released Judas and the Black Messiah about how the FBI and local law enforcement targeted the Black Panthers and put a bullet in the back of the head of Fred Hampton after he was apparently drugged by the informant. In MLK/FBI (2020), director Sam Pollard used newly declassified files to fill in the gaps on the story of the U.S. government’s surveillance and harassment of Martin Luther King, Jr. Days ago, The Washington Post reported the daughters of assassinated civil rights leader Malcolm X requested his murder investigation be reopened in light of a deathbed letter from officer Raymond A. Wood, alleging New York police and the FBI conspired in his killing.

During the closing credits of The United States vs. Billie Holiday we read that Holiday, played passionately by Andra Day in the film, was similarly arrested on her deathbed. She was in the hospital suffering from cirrhosis of the liver when she was cuffed to her bed. They don’t mention police had been stationed outside her door barring family, fans, and well-wishers from offering the singer comfort as she lay dying. They also don’t mention that police removed gifts people brought to the room, as well as flowers, radio, record player, chocolates, and any magazines. When she died at age 44, it was found that Holiday had 15 $50 bills strapped to her leg, the remainder of her money after years of top selling records. Billie intended to give it to the nurses to thank them for looking after her.

As The United States vs. Billie Holiday points out, the feds had been watching Holiday since club owner Barney Josephson encouraged her to sing “Strange Fruit” at the integrated Cafe Society in Greenwich Village in 1939. Waiters would stop all service during the performance of the song. The room would be dark, and it would never be followed by an encore.

The lyric came from a three-stanza poem, “Bitter Fruit,” about a lynching. It was written by Lewis Allan, the pseudonym of New York schoolteacher and songwriter named Abel Meeropol, a costumer at the club. Meeropol set the words to music, and the song was first performed by singer Laura Duncan at Madison Square Garden.

Holiday and her accompanist Sonny White adapted Allan’s melody and chord structure, and released the song on Milt Gabler’s independent label Commodore Records in 1939. The legendary John Hammond, who discovered Holiday in 1933 while she was singing in a Harlem nightclub called Monette’s, refused to release it on Columbia Records, where Billie was signed.

The song “marked a watershed,” according to David Margolick’s 2000 book Strange Fruit: Billie Holiday, Cafe Society, and an Early Cry for Civil Rights. Influential jazz writer Leonard Feather called the song “the first significant protest in words and music, the first significant cry against racism.”