#it becomes increasingly evident through ruin that he's a character who belongs in a different genre of book altogether

Text

Still can't get over Djoseras's character arc. Heroically tragic, morally invalidated - structurally genius, since we rediscover him at the same speed Oltyx does, layer by layer as he peels his deceptions away. There is something deeply unhinged about the way Djoseras saw life while he himself was alive, in a way the standard necron contempt towards organics can't match.

He's merciless. He's loving. He's a rival, he's a mentor, he's untrustworthy. He's the best brother Oltyx could have had. He's a mirror for princes. Most of what he says is wrong, because he does not know better, or a lie, because his princehood is an unwilling burden and has become a fundamental dishonesty. He's a terrible DJ. His best friend was his enemy. Spiritually he has joined his brother in exile, setting himself apart in the landscape closest to Sedh their crownworld has to offer. His malice is almost entirely in Oltyx's imagination. He wasn't thinking about how wrong he was about everything 'since [he and Oltyx] spoke in the desert'. He's actually been thinking about it since Oltyx got exiled, spending hundreds of years carving apologies upon his own soldiers. They're even less capable of protesting whatever he brings upon them than they would have as necrontyr. They're not the people he destroyed, and not the people who can grant him forgiveness. If they could throw aside their hierachies and see one another person-to-person, they wouldn't owe him a damn thing, and he knows that and it kills him which is just as well because Oltyx killed him too.

His best-lived self belonged entirely to Oltyx. And Oltyx forgot about him, twisted the memories into something he was not, and he locked Djoseras away where neither he nor his elder brother could reach until it was too late. (Though the moral teachings kept leaking out, like pus from a wound.) Djoseras was already dead from the moment we saw him in the desert. In a way, he too is a 'twice-dead king', except he never wished to be a king and so he just keeps dying and dying until there's nothing more of him left to die. But they're necrons. They're all dead. They don't change, they never come back, only Oltyx can come back and not in a form commonly acknowledged as necron. Djoseras would've had a hard time without being as inflexible as he was, but that was the path he chose and broke like iron he did. There are not enough tears in the world

#warhammer 40k#the twice dead king#oltyx#djoseras#necrons#essay#i find the moral dimensions of djoseras really interesting#it becomes increasingly evident through ruin that he's a character who belongs in a different genre of book altogether#he's a homeric hero in a homeric inspired world. like hektor breaker of horses. djoseras breaker of immortals.#you know that scene where hektor's son cries in fear at seeing his battle-helmet? that's djoseras and oltyx in the dril-yard#but alas the twice dead king is not a homeric epic but rather a deconstruction and djoseras's morals eventually have little place in it#yet i like that his nobility is never diminished. i like that he is still a moral core for oltyx to the very end and oltyx's final strength#and i even like that he is still high-minded and snobbish to the very end because it sells me to his iron will. changed but not enough.#but still recognizably djoseras. there are not many among necrons who have the privilege of dying as themselves after all

30 notes

·

View notes

Note

For Eti Adi & Kadin, if you'd be willing to answer for all 3! - 23. How does your character view death? Have they ever had to attend a funeral? If they were tasked with organising the funeral for someone, what manner of rites would they have performed? Do they believe in an afterlife? What about the Raise spell - do they believe it can be used, at all, or for the forces of good? Would they consent to being Raised themself?

FFXIV: ARR character asks!

One of my favorite subjects, thank you for the ask, @trahearnes ! What’s this, an excuse to lore-dump from my notes about my characters?! Sign me up!

Growing up in Ishgard, Etienne attended their share of funeral masses. The ones that hit hardest were young people cut down in the war - or due to complications of the cold and poverty of the Brume - before they ever really had a chance. As Etienne was the only living relative of their adoptive mother, they arranged for her funeral after caring for her long-term as she died of liver disease. They don’t remember that funeral particularly clearly as they were suffering tremendously from alcohol withdrawal at the time.

Despite being raised in the Church, Etienne has never felt particularly connected to Halone, especially as they grew up and grew increasingly aware of the hypocrisy endemic to Her followers. Etienne instead became devoted to Nald’thal, particularly the aspect of Thal, after witnessing a sermon at Arrzaneth Ossuary. They are not only a thaumaturge in the sense of being able to do the magic, but as a spiritual calling. They believe it is their duty to look after the dead - not so different from what they once did in Ishgard. They feel a sympathy and closeness with the dead. They view death as an integral part of life, and in fact find it comforting that their life will, must, eventually end. In fact they actually find death to be incredibly beautiful in a way that’s difficult to articulate. Etienne has trained in the rituals of the dead quite extensively, and when they worked as an adventurer, considered it an extension of their duty to help lay any dead to rest, regardless if they’d been enemies before. They would also take on the task of taking any belongings back to loved ones of the deceased, etc. Because of this, they’ll do their best to perform whatever practice would be what the dead wished for, and attempt to find out if they cannot answer that question.

Etienne believes the teaching of the Ossuary, that all must go before Thal for judgment in order to be welcomed to His halls. To Etienne, there is an important distinction in being welcomed to Halone’s bosom because you were virtuous, and being judged by Thal as worthy because of the proof of what you accomplished in life. They also stress that the emphasis on prosperity and material gain is intentionally misinterpreted by many in Ul’dah.

During Etienne’s thaumaturge training, not only did they learn about looking after the dead, but they handled threats of voidsent and so on. Having seen a voidgate open on more than occasion, Etienne is adamantly against any activity that could potentially let something through, and to them, that would be allowing a soul to get shoved back into a body after the aether was exhausted and the spirit temporarily fled. They are adamantly against any kind of magic approaching necromancy, and think Raise would be skirting the line. That being said, they’d consider it a genuine crisis of faith if faced with losing someone they cared for when they had an option to bring them back.

I think they would similarly struggle with whether or not they would want to be Raised. On paper, according to their own beliefs, they should go to Thal and accept their death. And yet, who would be able to accept that fate when faced with the option to accomplish a little bit more?

Adi has a more neutral stance on death - it’s neither good or bad, it’s an inevitable circumstance, like the weather. You can curse it all you like but it doesn’t lessen its effects. Having honed his healing skills by being forced to endure torture and life-threatening injuries, as well as watching members’ of his family fall apart mentally and physically during the prologued hereditary, and thus far terminal illness, has deeply affected his own view on his mortality. He’s both aware of how fragile a mortal can be, and how much they’re capable of enduring. Even as a dangerously powerful conjurer, he’s aware of his own limitations, and that some things (the life of his mother, his eye) cannot be saved. Best not to dwell on that, do what you can and be satisfied with that if possible.

Spiritually, he believes that the latent aether within all living things returns to the lifestream, and that aether is reused in all living things. The dead should also be reused, and all dead family members are placed in a shallow crypt beneath the roots of a great caretaker tree that provides food and air to all who choose to live in the ruins deep, deep underground. The faces of the dead appear in the bark of the tree, and thus they are never ‘gone’. However, it would be a tragedy for someone in the family to not be returned to the crypt, because they could not then ‘feed’ the rest of the family, or be remembered. Adi has also witnessed some evidence that some part of these family members is actually ‘alive’ within the tree, able to move and respond to being spoken to, although he is the only one who’s been able to see it. Because of this, sometimes he has trouble remembering his mother is actually dead, as when he goes home to visit his family, he is apparently able to speak with her.

He would wish to be Raised because is his family’s hope for survival. Maybe they don’t deserve it, but he takes it seriously.

Kadin’s clan has practiced ritual cannibalism for as long as they can remember as a way to respect the dead, and also to avoid burying people somewhere that would upset the elementals in the Shroud. They lived in a way so as to intentionally avoid wasting anything that could not be given back to the Shroud. Most of their spiritual practices were abandoned after the Calamity, as their leadership and way of life changed after the death of their leader (Kadin’s aunt) and the most powerful huntresses (her daughters) - it became immediately noticeable after the disaster that the elementals weren’t as strong as they once were, so the strictness of their drive to coexist with them changed. Kadin’s mother, who took over the tribe after the death of her sister, believed that these practices were barbaric and others would look down on them for doing it, and put an end to it.

Kadin believes that others literally live on after death because of how much of their essence was taken in by others, whether this involves consuming of the flesh of the dead, blood brotherhood, having children, or simply… combining… essence… in another manner. Like with dicks. In order to become truly strong, and understand others, you should take a part of them into you. When you die, you’re reborn, and are mostly a blank slate, but you’ll contain the essences of others within you and that will form who you ultimately are. For obvious reasons, he avoids discussing this, or practicing this, openly.

Kadin would want to be Raised so he can keep fighting! But he would also be alright with dying at this point, as he’s shared enough of his essence with others that he’s sure he’ll live on somehow.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Ongoing Narrative Evolution of Attack on Titan

Hajime Isayama’s Attack on Titan (or Shingeki no Kyojin, if you’d like) is, at first blush, little more than a particularly smart and stylish take on the usual apocalyptic-horror formula: existentially-terrifying monsters in a world already lost, with a heap of unanswered questions. This conceit is ubiquitous these days; it’s at the core of hundreds of zombie and zombie-like apocalypse narratives scattered across a dozen different mediums.

How did world get into this mess? How does one survive in a world like this? Is it possible for society to survive in a situation like this? These questions form the backbone of fiction like Attack on Titan— internally within the narrative itself and externally in how the audience engages with it. One of the fundamental weaknesses of most zombie-like narratives is an inability to move past this core conceit and answer any of the questions. Few even try— as to do so might undermine much of the fundamental appeal of the narrative: the life-of-death tension and unknowable nature of the mystery.

Attempting to evolve the narrative past the status quo (no matter how unstable that status quo may logically be) runs the risk of alienating an audience who became engaged with the work because of that status quo in the first place. Oftentimes, the questions raised are far more interesting than the answers, and authors sometimes have no actual answer in mind when they ask these broad-sweeping questions in the first place. At the same time, maintaining a status quo indefinitely is boring; it’s at the core of why zombie fiction is so same-y and garbage.

One of the things that’s most remarkable to me about Attack on Titan is how it is not only willing to abandon the initial status quo, but continually evolve and develop the concept of the narrative while not betraying the themes and events it began with. It’s natural in a way that most apocalyptic monster stories aren’t. It continually raises more nuanced, challenging questions while answering older ones, and each new status quos raised is as perilous as the one that preceded it— just more complicated and nuanced.

Very little of what I’m talking about here is particularly revelatory if you’ve been keeping up with Attack on Titan, and if you haven’t been this discussion is going to amount to little more than the world’s strangest Cliffs Notes. I just want to nail down just how much Attack on Titan has been successfully evolving its themes while staying engaging, largely for my own satisfaction having just recently caught up. Spoilers for Attack on Titan through Chapter 98 after the break.

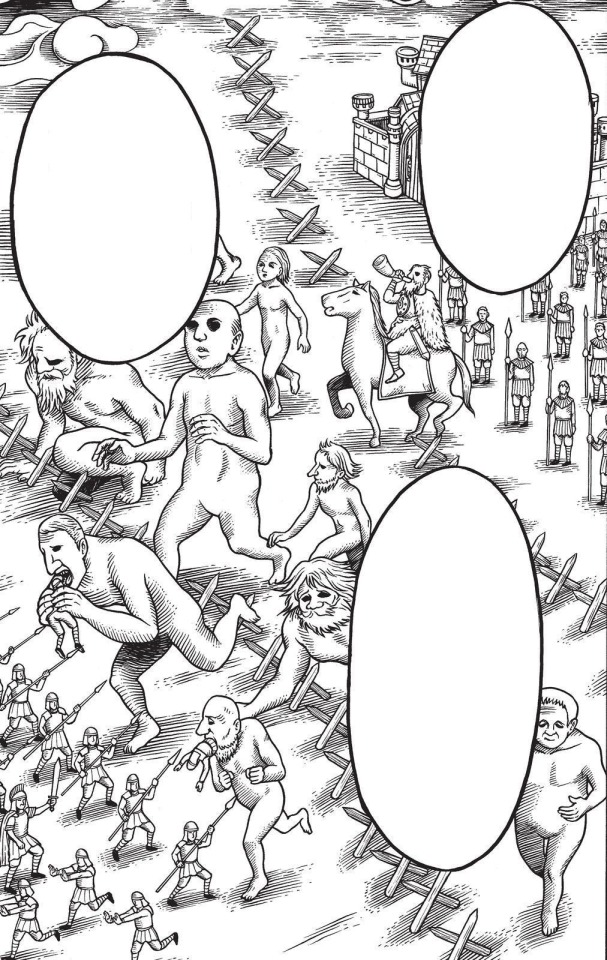

Much of Attack on Titan’s initial appeal came from its basic aesthetics. The imagery of sword-wielding techno-spider-men fighting giant naked man-eating men is at the core of why the anime was instantaneously popular, and why the manga blew up in the first place. But it’s fascinating how quickly it moved past being just that. In a way, Attack on Titan has undergone a continuous, evolutionary process— resulting in increasingly complex thematic phases that we can point to.

The initial premise was the simplest. The last remnant of humanity lives in a walled city that keeps horrible man-eating giants out. Life sucks. Then the titans breached the walls! The lead character, Eren, becomes an orphaned refugee after a titan eats his mother right in front of him, and enlists in the scout legion to try to get his home back, and get his revenge. But things suddenly turned in just a single volume’s time, when by a titan eats Eren… and inexplicably he transforms into an intelligent, sentient titan who wrestles the bad ones!

The immediate reaction by many to this twist was rather negative— which isn’t that surprising. After all, it seemingly undoes the base premise of the series, and forces another greater suspension of disbelief just after people had come to terms with Attack on Titan’s definition of “reality.” Isayama sold them a bill of goods that promised nasty naked boys eating spidermen; a sudden twist towards what first glance seemed to be rank power fantasy of “I AM THE NAKED GIANT BOY NOW, I SHALL DESTROY THE GRAVEYARD SMASH” was something of a ‘betrayal’ of the darker themes that had brought them in in the first place.

But those who gave this course change a chance discovered that rather than the narrative becoming simpler, it was WAY MORE COMPLICATED. Before Eren became a titan, we had no idea what the titans were, or where they came from. After he became a titan, we had even less of an idea, as the evidence we now had was so fragmentary and seemingly contractor as to defy most speculation. The general question of the setting (“How?”) became an outright mystery (“What!?”). What was the connection between humans and titans, and how the hell did Eren manage to turn into one and back again?

This turn also really kicked off what’s been a central aspect of Attack on Titan ever since: politics. The revelation of Eren’s ability was an incredibly political one; what was to be done with him, and what was the motivation of those now wanting him dead? The revelation that there was in fact a deeper connection between titans and humans suddenly brokered a great deal more suspicion in the actions of both the humans and the titans.

This paid off with the next major twist, when an expedition attempting to make use of Eren’s abilities was attacked by another titan that seemed to be under human control; others had the same ability as Eren! The narrative shifted from being “man vs monsters” to “man vs man, contextually monsters” as the titans took a role less as primary threat and more a backdrop for the conflict. That these “manned titans” seemed to be behind the deliberate compromising of the wall years previously resulted in a massive shift in the overall tone and nature of the mystery. The existential question was now less “Why is the world like this?” and more “Why would someone do this?” and “Who did this?”

The conflict was no longer us vs an inhuman them; who the enemy was no longer as clear. Who could Eren, and us by extension, trust? Those in charge seemed awfully like they knew way more than they let on, and it turned out that several of Eren’s compatriots from his training were the titan-changer sleeper agents, and were those who caused his family and thousands of others to die. But even stranger, these titan-changers in their midst impossibly came from some place outside the walls— which contradicted all we knew about the outside world.

But we had little time to dwell on this, as Eren and the scouting legion… initiated a coup de ’tat!? The government was quite clearly complicit in the state of things, willing to throw away millions of lives to maintain the precarious status quo and keep their hold on power. To do so, they attempted to seize Eren, triggering the coup. This finally moved the conflict to one purely “man vs man”, with the titans becoming little more than raison d'être. The coup ultimately culminated with the crowning of a new, more cooperative monarch, and the revelation that the nation’s isolation and regressive state was foisted upon it by its former rulers. We also began to learn more of the true nature of the titans: that they are created, that the power to become a titan can be transferred, and that it all somehow ties into the overthrown royal bloodline.

It seemed like oh so soon, we would be able to answer the ultimate mystery of the world. Eren gained his titan power thanks to a serum his father had given him right after the first wall collapsed, he seemingly having come from some place outside the walls just like the titan-changers. All the scouting legion needed to do now was take back the wall that had fallen all those years ago, and pull from its ruins the lost secrets of Eren’s father. Unfortunately, the titan-changers too knew of this goal, and it culminated in a pitched battle of titan versus titan and man versus titan, against those who had destroyed the wall.

The victory, at tremendous cost, brought the greatest revelations and shifts in the narrative of all: the conflict had always been one of man vs man. The walled nation that they thought was the last bastion of humanity? Little more than a single isolated kingdom, whose citizenry was of a seemingly cursed bloodline with the ability to transform into mindless titans— as well as to inherit the ability to become an intelligent titan. The titans hadn’t destroyed the rest of the world; they were amid an industrial revolution! The titans on the island were little more than dissidents from a beleaguered ethnic minority, transformed into monsters and released there as a last cruel insult to a nation that once ruled the world.

And now we truly see that nation at large. Those once oppressed by the titans now use them as weapons in World War I-era armed conflict, turning non-citizens kept in ghettoes into living weapons in an exploitative military machine. It’s far beyond the simple cruelty of man fighting monsters; true horror always belongs to the cruelty of mankind alone. Eren and his homeland don’t need to kill all the titans, or even defeat some narrowly-defined enemy; the world is their enemy. By their very birth, they are hated, used, and discarded. And how do you fight that? You can’t spiderman that away.

It seems their answer is to repay it in kind. Eren has infiltrated the home of those titan-changers who had once infiltrated his own. To what end? We don’t know yet. But I’m really fascinated to find out; it’s a total inversion of the concept we started with, and it took a hell of a ride to get here and have it feel like a natural extension.

19 notes

·

View notes