#in flanders were taught French at school

Note

J'adorerais parler le Wallon, mais je connais seulement un couplet de chanson :( J'aurais aimer en apprendre plus à l'école.

Je sais me lire sur les panneaux en général, ça ressemble beaucoup à un accent de ma région. Il y a des pancartes avec des petits proverbes dans ma ville, j'adore les lire.

Ma maman a quelques expressions amusantes en wallons, par exemple "dji vou, dji n'pou" pour dire qu'on veut faire quelque chose mais qu'on en est pas capable. Mon papa est Bruxellois et a des expressions totalement différentes, ce qui fait que pon frère et moi utilisons un mélange bizarre d'accents et de patois.

J'aime bien le français, mais je ne le parle pas comme les Français évidemment. Je trouve toujours que ça a plus de sens de parler de déjeuner, dîner et souper que de petit-déjeuner, déjeuner et dîner. Duolingo utilise le français de France cependant, donc je fais sans arrêt des erreurs avec les noms des repas quand j'apprends d'autres langues.

We have these differences between Flemish and Dutch too. It's not always easy. I wish they were taught more at schools too.

But Wallon will always be superior because of septante et nonante 🙌

Anyway, I like that expression!

#in flanders were taught French at school#but it would be cool if they actually focused more on Walloon#I think I would've liked it more#but then dialects are harder to teach so i get it but .. yakno .. more fun#ask#french#walloon#belgian#spyld posts

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

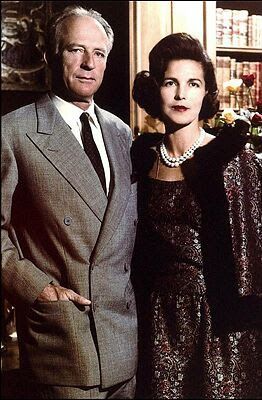

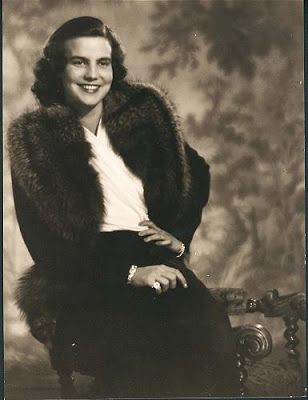

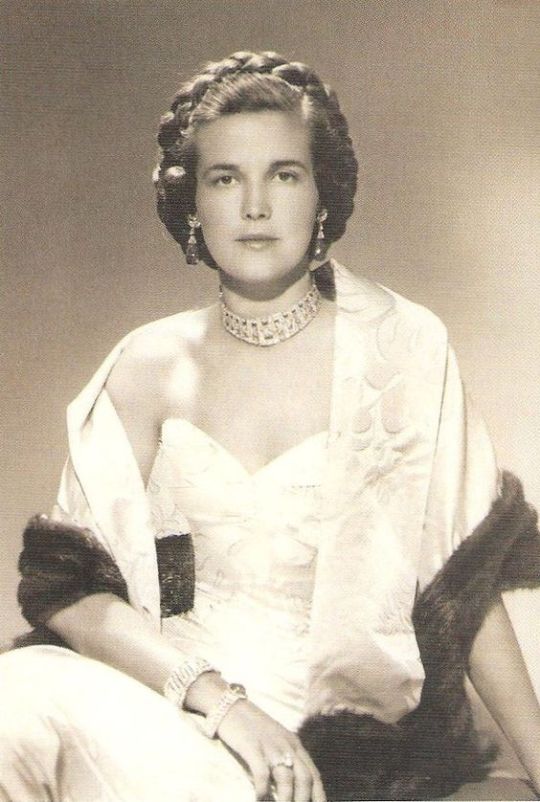

People that have married in to Royal Families since 1800

Belgium

Mary Lilian Baels

Princess Lilian of Belgium better known as Lilian, Princess of Réthy, was the second wife of King Leopold III of the Belgians.

Mary Lilian Baels was born in London, England, where her parents were living at the time. She was one of the nine children of Henri Baels and his wife, Anne Marie de Visscher. Lilian was initially educated in English, but, upon her parents' return to Belgium, she attended a school in Ostend, where she learned Dutch.

She continued her studies in French in Brussels. She completed her education by attending a finishing school in London, the Holy Child. In addition to academic work, Lilian participated extensively in sports, such as skiing, swimming, golfing, and hunting. Above all, however, she enjoyed, as did her father, literature and the arts.

As a teenager, she was presented to King George V and Queen Mary of the United Kingdom at Buckingham Palace

In 1933, Lilian saw her future husband, King Leopold III of the Belgians, then still Duke of Brabant, for the first time during a military review. A few years later, when her father, then Governor of West Flanders, took his daughter to a public ceremony, she had the occasion to meet King Leopold, who presided at the event, for the second time. In 1937, Lilian and her mother met the King, now a widower, again on another ceremonial occasion. Soon afterwards, King Leopold III contacted Governor Baels to invite he and his daughter to join him in a golfing party the next day. Lilian also saw the King in 1939 at a garden-party organised in honour of Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands, and later at the golf course at Laeken, where she was invited to lunch by Queen Elisabeth of Belgium, King Leopold's mother. A final golf party near the Belgian coast occurred in May 1940, shortly before the Nazi invasion of Belgium.

In 1941, at the invitation of Queen Mother Elisabeth, Lilian visited Laeken Castle, where King Leopold III, now a prisoner of war, was held by the Germans under house arrest. This visit was followed by several others, with the result that Leopold III and Lilian fell in love. Leopold proposed marriage to Lilian in July 1941, but Lilian declined his offer. "Kings only marry princesses," she said. Queen Elisabeth, however, prevailed upon Lilian to accept the King's offer. Lilian agreed to marry the King, but declined the title of Queen. Instead, the King gave her the unofficial title "Princess of Réthy." It was agreed that any descendants of the King's new marriage would be excluded from succession to the throne. Leopold and Lilian initially planned to hold their official, civil marriage after the end of the war and the liberation of Belgium, but in the meantime, a secret religious marriage ceremony took place on 11 September 1941, in the chapel of Laeken Castle Although Lilian and Leopold had originally planned to postpone their civil marriage until the end of the war, Lilian was soon expecting her first child, necessitating a civil marriage, which took place on 6 December 1941.

Lilian proved a devoted wife to the King and an affectionate and vivacious mother to his children by his first wife, Queen Astrid. When the civil marriage of Leopold and Lilian was made public in a pastoral letter by Cardinal van Roey read throughout Belgian churches in December 1941, there was a mixed reaction in Belgium. Some showed sympathy for the new couple, sending flowers and messages of congratulations to the palace at Laeken Others, however, argued that the marriage was incompatible with the King's status as a prisoner-of-war and his stated desire to share the hard fate of his conquered people and captive army, and was a betrayal of Queen Astrid's memory. They also branded Lilian as a social-climber. Leopold and Lilian were also blamed for violating Belgian law by holding their religious marriage before their civil one. These criticisms would continue for many years, even after the war. Queen Astrid's parents, the Duke and Duchess of Västergötland, did not take the hard line against King Leopold's remarriage. Princess Ingeborg told a Belgian journalist that she couldn't understand all the animus in Belgium against the king's second marriage, that it was perfectly natural for a young man not to want to remain alone forever. She said she was happy about her former son-in-law's new marriage, both for his own sake and for the sake of her grandchildren.

In 1944, the Belgian royal family was deported to Nazi Germany, where they were strictly guarded by 70 members of the SS, under harsh conditions. The family suffered from a deficient diet and lived with the constant fear that they would be massacred by their jailers, as an act of revenge on the part of the Nazis, angered at their defeat (by now becoming increasingly certain) by the Allies, or that they would be caught in the cross-fire between Allied forces and their captors, who might try to make a desperate last stand at the site of the royal family's internment. The family's fears were not unfounded. At one point, a Nazi official tried to give them cyanide, pretending it was a mixture of vitamins to compensate for the captives' poor diet during their imprisonment. Lilian and Leopold, however, were rightly suspicious and did not take the pills or give them to their children. During their period of captivity in Germany, (and later Austria), Leopold and Lilian jointly homeschooled the royal children. The King taught scientific subjects; his wife, arts and literature. In 1945, the Belgian royal family was liberated by American troops under the command of Lieutenant General Alexander Patch, who thereafter became a close friend of King Leopold and Princess Lilian.

Following his liberation, King Leopold was unable to return to Belgium (by now liberated as well) due to a political controversy that arose in Belgium surrounding his actions during World War II. He was accused of having betrayed the Allies by an allegedly premature surrender in 1940 and of collaborating with the Nazis during the occupation of Belgium. In 1946, a juridical commission was constituted in Brussels to investigate the King's conduct during the war and occupation. During this period, the king and his family lived in exile in Pregny-Chambésy, Switzerland, and the King's younger brother, Prince Charles, Count of Flanders, was made regent of the country. The commission of inquiry eventually exonerated Leopold of the charges and he was able, in 1950, to return to Belgium and resume his reign.

Political agitation against the King continued, however, leading to civil disturbances in what became known as the Royal Question. As a result, in 1951, to avoid tearing the country apart and to save the embattled monarchy, King Leopold III of the Belgians abdicated in favour of his 21-year-old son, Prince Baudouin. In the first nine years reign of her stepson, King Baudouin, Lilian acted as First Lady of Belgium and manages the life of the Court with firmness and refinement, but she never be loved by the Belgians. The ex-King Leopold and Princess Lilian continued to live in the royal palace at Laeken until the marriage of Baudouin to Doña Fabiola de Mora y Aragón in 1960.

In 1960, following the marriage of King Baudouin, Leopold and Lilian moved out of the royal palace to a government property, the estate of Argenteuil, Belgium. Lilian employed various designers to transform the dilapidated mansion on the property into a distinguished and elegant residence for the ex-King. Argenteuil became a cultural centre under the auspices of Leopold and Lilian, who cultivated the friendship of numerous prominent writers, scientists, mathematicians, and doctors. Leopold and Lilian also travelled extensively all over the world.

Following her son Alexandre's heart surgery in the United States during his childhood, Princess Lilian became very interested in medicine, and, in particular, in cardiology, and founded a Cardiological Foundation which, through its work, has saved the lives of hundreds of people.

Both before and after her husband's death in 1983, Lilian pursued her interests in intellectual and scientific spheres with energy and passion

Lilian was known as a woman who was terribly strict and demanding towards herself, and, a result, as one who could be excessively severe with others as well. Due to the controversy surrounding King Leopold's wartime actions, and, in particular, his second marriage, Lilian was widely unpopular in Belgium. She also, however, had a circle of close friends, who saw her as a woman of great beauty, charm, intelligence, elegance, strength of character, kindness, generosity, humor and culture. They admired her for the courage and dignity with which she faced a long series of personal attacks, both during the Royal Question and for decades afterwards

Princess Lilian died at the Domaine d'Argenteuil in Waterloo, Belgium. Before her death, she had expressed the desire to be buried at Argenteuil. Her wish was denied, however, and she was buried in the royal crypt of the Church of Our Lady, Laeken, Belgium, with King Leopold and his first wife, Queen Astrid.

Queen Fabiola and Lilian's stepchildren attended the funeral, as did Lilian's son Alexandre and her daughter Marie-Esmeralda. Lilian's long-estranged daughter Marie-Christine did not attend. Following Princess Lilian's death, a cardiological conference was organised and prominent doctors and surgeons such as DeBakey and many others rendered an homage to Lilian and her contributions to cardiology.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

History through Philately – Indian Air Warriors of World War I

Every stamp tells a story. Along with these small, multi-colored pieces of paper come the long, adventurous and out of the ordinary chronicles. These valuable pieces of collectibles unfold the entire journal of past events that collectively tell us lesser-heard stories. They have become unusual pieces of evidence of past and the narrators of modern history. The story that the stamps are telling today is the story of a great war. The war that began as a conflict between the participant countries over the interest of territory turned into a big turmoil that dragged the whole world. Even, the counties which stayed neutral did not remain unaffected. It has been100 years since the armistice of 11 November 1918 ended, but there are still many untold stories of this Great War. One of the participating countries was Great Britain! This tiny country that played many pivotal roles in the war had a gigantic help. India! The jewel in the British Crown! The fuel in this never-stopping machine! The source of all the power of Great Britain!

India directly or indirectly supported the war by being the supplier of animals, jute, cotton, explosives and most importantly the finances. The year 2019 celebrates the completion of the 100th years of the World War I. Hence, to commemorate the centenary of the completion of the war, India Post issued a series of stamps namely “Indian Air Warriors of World War I” which focuses on the key roles played by Indian Air Warriors of World War I.

Indian Air Warriors:

A number of fighter from India in World War I was in millions. Approximately 1.5 million Indians fought in every theatre of the conflict. Little do the people know that a handful of Indians fought in the air! There seems to be little awareness about the role of India’s air warriors in the Great War. Four almost-forgotten Indians flew as combat pilots: Lieutenant Hardit Singh Malik, Lieutenant SC Welinkar, Second Lieutenant E.S.C. Sen and Lieutenant I.L. Roy, DFC.

Lieutenant Hardit Singh Malik:

Lieutenant Hardit Singh Malik was the first Indian to fly as a pilot in the Royal Flying Corps during the First World War. Born on 23rd November 1894 in a Sikh family of Rawalpindi (Now in Pakistan), H. S. Malik’s career choice was influenced by his father who was strongly attached to the Sikh faith. His parents also taught their young son the importance of independence as a great virtue and labor of all kinds as an honor. At the age of 14 years, Hardit Singh left his blessed childhood and went to Britain in the pursuit of higher learning.

The time he completed his second year of college at Oxford University, the War broke out. Through the help of his college tutor, Francis Urquhart, he volunteered for service in the French Red Cross. He started out by driving a motor ambulance donated by Lady Cunard to the French Army: where he stayed for a year. In due course, he looked to join the French forces, preferably the Air Force. With the further intervention of his tutor, Hardit Singh became Hon. 2/Lt H. S. Malik, RFC, Special Reserve, on 5 April 1917. Not only was he the first Indian in any flying service in the world, but he was also the first non-Brit with turban and beard to become a fighter pilot – which was against every British Army regulation of the day.

Malik was selected as a scout (as fighter pilots were then called), and posted to an RFC squadron flying Sopwith Camels, the most iconic British aircraft of the war. He went into action on September 1917, initially from the famous St Omer airfield and then from Droglandt in Belgium. In one such fight, Malik shot down one enemy aircraft, but at least four others attacked him. Malik got shot down in the leg and crashed but was rescued and carried to the hospital. After his recovery, He continued flying and returned to France for more operational service.

He survived to see India achieving independence and went on to distinction in independent India, serving as India’s first High Commissioner to Canada and later as Ambassador to France, highly-respected by British, Canadian and European comrades-in-arms. This flying ace died in New Delhi on 31 October 1985, three weeks before his 91st birthday.

Lieutenant Indra Lal Roy:

Known as India’s ‘Ace’ Over Flanders, Lieutenant Indra Lal Roy was one of Indian World War I flying ace was a gifted combat pilot who served in the Royal Flying Corps and claimed 10 aerial victories – all in a span of two weeks in July 1918. Born on 2nd December 1898, Indra Lal Toy grew up in Calcutta in the household of a barrister. His family was originally from the Barisal district in present-day Bangladesh. His family also lived in London for some time. When World War One broke out, he was still in school, at the 400-year-old St. Paul’s outside London. Shortly after turning 18, Roy joined the Royal Flying Corps (RFC), which was a corps of the British army. He was commissioned in 1917 when he was barely 19 years old.

One of his experiences in the war is frightening and breathtaking. In late 1917, while he was still a rookie, he was posted to No. 56 Squadron RFC. He was knocked unconscious, taken for dead and actually laid out with other dead in a morgue. When he came to, he banged on the morgue’s locked door and shouted for help in schoolboy French. The morgue attendant was so frightened by this apparent resurrection from the dead that he did not open the door till he had a back-up.

After his recovery, he returned to duty on June 1918, he was posted to No 40 Squadron. Over the next two weeks, as mentioned, Roy achieved ten victories, of which two were shared with McElroy. However, this mission turned out to be the last one. On July 22, 1918, Roy took off for dawn patrol information with two other SE5as. The patrol was attacked by four Fokker DVI. Two of the attackers were shot down, but Roy was seen going down in flames over Carvin. L. Roy served death as a hero. He sacrificed his life for the mother nation. He was still four months short of his 20th birthday. Roy was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross in September 1918. The armistice ended World War One on November 11, 1918, three weeks before Roy would have turned 20. While serving in the Royal Flying Corps and its successor, the Royal Air Force, he claimed ten aerial victories; five aircraft destroyed (one shared), and five ‘down out of control’ (one shared) in just over 170 hours flying time.

Lieutenant S.C. Welingkar:

Along with Lt. Roy and Lt. Hardit, another name that is taken by the Indian Air Force with great pride and respect is Lieutenant S.C. Welingkar. Although very little information is available about one of the best Indian Air Warriors of World War I. Lieutenant S.C. Welingkar was the brave soldier from Bombay, Maharashtra. He was joined the Air Force a little earlier than Lt. Roy but were on the same mission. He was shot down on 27 June 1918 in Dolphin D3691 by Fritz Rumey and Died of Wounds 30 June 1918. During his service, he was awarded the Military Cross. His death in action is commemorated at the Hangard Communal Cemetery Extension, at Somme, France.

Lieutenant E. S. Chunder Sen:

Erroll Suvo Chunder Sen was an Indian pilot who served in the Royal Flying Corps and Royal Air Force during the First World War, and who was among the first Indian military aviators. Born in Calcutta, Lt. Sen was the Grand Son of the philosopher and social reformer Keshab Chandra Sen. At an early age, he moved with his mother, brother, and sister to England. He was educated at Rossall School in Fleetwood, Lancashire, where he joined its unit of the Officers’ Training Corps.

At the age of 18 years old, he applied or a commission in the Royal Flying Corps and was awarded a temporary honorary commission in the RFC as a second lieutenant. After two months at Reading, followed by 25 hours of elementary flying training and 35 hours in front line aircraft, Sen was posted to the Western Front along with Lt. Roy and Lt. Welingkar. He was appointed as a Flying Officer in the RFC with the temporary rank of second lieutenant.

While he was taking part in an offensive patrol, Sen experienced engine failure and dropped behind the rest of his patrol. In the attempt to catch up with the remainder of the patrol, he was lost in a cloud and was attacked by 4 enemy machines. He was hit & crashed outside Menin (outside Belgium Province). He was interned in Holzminden prisoner-of-war camp for the remainder of the war. He was eventually repatriated to the UK on 14 December 1918 (i.e. after the end of the war).

Following his repatriation, Sen was promoted lieutenant on 17 April 1919, and was transferred to the unemployed list of the RAF He returned to India and joined the Indian Imperial Police as an assistant superintendent (junior scale, on probation) with effect from 20 September 1921. Lt. Sen also witnessed World War II and was doing a war duty. Here ends his story as no news or information about his death has come forward. It is believed that he spent his last days in Burma and tried to walk out of the country, and is believed to have died in the attempt.

Sadly, very little is known about Indian Air Warriors of World War I, beyond the bare facts, in British records. They were from well-off families, attending prestigious schools or universities in the UK. They fought gallantly, served their duties responsibly and faced their future with courage.

A Grad Salute to Indian Air Warriors of World War I!

Share

The post History through Philately – Indian Air Warriors of World War I appeared first on Blog | Mintage World.

0 notes

Text

THE CANTERBURY TALES

A MINIMALIST TRANSLATION

Forrest Hainline

GENERAL PROLOGUE

1 When that April with his shower’s sweet

2 The drought of March has pierced to the root,

3 And bathed every vein in such liquor

4 Of which virtue engendered is the flower;

5 When Zephirus too with his sweet breath

6 Inspired has in every holt and heath

7 The tender crops, and the young sun

8 Has in the Ram his half course run,

9 And small fowls making melody,

10 That sleep all the night with open eye

11 (So pricks them Nature in their courage) :

12 Then long folk to go on pilgrimage

13 And palmers for to seek strange strands,

14 To foreign hallways, known in sundry lands;

15 And specially, from every shire's end

16 Of England, to Canterbury they wend,

17 The holy blissful martyr for to seek

18 That them has helped, when that they were sick.

19 Befell that in that season on a day,

20 In Southwerk at the Tabarad as I lay

21 Ready to go on my pilgrimage

22 To Canterbury with full devout courage,

23 At night was come into that hostelry

24 Well nine and twenty in a company

25 Of sundry folk, by adventure to fall

26 In fellowship, and pilgrims were they all,

27 That toward Canterbury would ride.

28 The chambers and the stables were wide,

29 And well we were eased at best.

30 And shortly, when the sun was to rest,

31 So had I spoken with them everyone,

32 That I was of their fellowship anon,

33 And made forward early for to rise,

34 To take our way there as I you devise.

35 But nonetheless, while I have time and space,

36 Ere that I further in this tale pace,

37 Me thinks it according to reason,

38 To tell you all the condition

39 Of each of them, so as it seemed me,

40 And which they were, and of what degree,

41 And eek in what array that they were in;

42 And at a knight then will I first begin.

43 A knight there was, and that a worthy man

44 That from the time that he first began

45 To ride out, he loved chivalry,

46 Truth and honor, freedom and courtesy,

47 Full worthy was he in his lord's war,

48 And thereto had he ridden, no man as far,

49 As well in Christendom as in heatheness,

50 And ever honored for his worthiness.

51 At Alexander he was when it was won;

52 Full oft time he had the board begun

53 Above all nations in Prussia;

54 In Lithuania had he raised and in Russia,

55 No Christian man so oft of his degree;

56 In Grenada at the siege too had he be

57 Of Algezir, and ridden in Belmarie;

58 At Ayas was he and at Attalie,

59 When they were won, and in the Great Sea

60 At many a noble army had he be.

61 At mortal battles had he been fifteen,

62 And fought for our faith at Tlemcen

63 In lists thrice, and aye slain his foe.

64 This same worthy knight had been also

65 Sometime with the lord of Paletey

66 Against another heathen in Turkey:

67 And evermore he had a sovereign prize.

68 And though that he were worthy, he was wise,

69 And of his port as meek as is a maid.

70 He never yet any villainy said

71 In all of his life, unto no manner wight.

72 He was a very perfect, gentle knight.

73 But for to tell you of his array,

74 His horse was good, but he was not gay.

75 Of fustian he wore a gipon

76 All bespattered with his habergeon;

77 For he was lately come from his voyage,

78 And went for to do his pilgrimage.

79 With him there was his son, a young Squire,

80 A lover, and a lusty bachelor,

81 With locks curly as they were laid in press,

82 Of twenty year of age he was, I guess.

83 Of his stature he was of even length,

84 And wondrously delivered, and of great strength.

85 And he had been sometime in cavalry,

86 In Flanders, in Artois, and Picardy,

87 And born him well, as of so little space,

88 In hope to stand in his lady's grace.

89 Embroidered was he, as it were a meadow

90 All full of fresh flowers, white and red.

91 Singing he was, or fluting, all the day;

92 He was as fresh as is the month of May.

93 Short was his gown, with sleeves long and wide.

94 Well could he sit on horse, and fair ride.

95 He could songs make and well endite,

96 Joust and dance too, and well portray and write.

97 So hot he loved that by nighter-tale

98 He sleeps no more than doth a nightingale.

99 Courteous he was, lowly, and serviceable,

100 And carved before his father at the table.

101 A Yeoman had he, and servants no more

102 At that time, for he pleased to ride so;

103 And he was clad in coat and hood of green;

104 A sheaf of peacock arrows bright and keen

105 Under his belt he bore full thriftily;

106 Well could he dress his tackle yeomanly:

107 His arrows drooped not with feathers low;

108 And in his hand he bore a mighty bow.

109 A knot-head had he, with a brown visage.

110 Of woodcraft well could he all the usage.

111 Upon his arm he bore a gay bracer,

112 And by his side a sword and a buckler,

113 And on that other side a gay dagger,

114 Harnessed well, and sharp as point of spear;

115 A Christopher on his breast of silver sheen;

116 A horn he bore, the baldric was of green.

117 A forester he was, truly as I guess.

118 There was also a Nun, a Prioress,

119 That of her smiling was full simple and coy.

120 Her greatest oath was but by Saint Loy;

121 And she was called Madame Eglantine.

122 Full well she sang the service divine,

123 Intoned in her nose full seemly;

124 And French she spoke full fair and fetisly,

125 After the school of Stratford at the Bowe,

126 For French of Paris was to her unknow.

127 At meat well taught was she withal;

128 She let no morsel from her lips fall,

129 Nor wet her fingers in her sauce deep.

130 Well could she carry a morsel, and well keep,

131 That no drop would fall upon her breast.

132 In courtesy was set full much her lest.

133 Her over-lip wiped she so clean

134 That in her cup there was no farthing seen

135 Of grease, when she drunk had her draft.

136 Full seemly after her meat she raft,

137 And certainly she was of great disport,

138 And full pleasant, and amiable of port,

139 And pained her to counterfeit cheer

140 Of court, and be stately of manner

141 And to be held worthy of reverence.

142 But for to speak of her conscience,

143 She was so charitable and so piteous

144 She would weep, if that she saw a mouse

145 Caught in a trap, if it were dead or bled.

146 Of small hounds had she, that she fed

147 With roasted flesh, or milk and wastel-bread.

148 But sore wept she if one of them were dead,

149 Or if men smote it with a yard smart:

150 And all was conscience and tender heart.

151 Full seemly her wimple pinched was;

152 Her nose tretis, her eyes gray as glass;

153 Her mouth full small, and thereto soft and red.

154 But certainly she had a fair forehead;

155 It was almost a span broad, I trow;

156 For hardily, she was not under grow.

157 Full fetis was her cloak, as I was ware.

158 Of small coral about her arm she bare

159 A pair of beads, gauded all with green,

160 And thereon hung a brooch of gold full sheen,

161 On which there was first writ a crowned A,

162 And after, amor vincit omnia.

163 Another nun with her had she,

164 That was her chaplain, and priests three.

165 A Monk there was, a fair for the mastery,

166 An outrider, that loved venery,

167 A manly man, to be an abbot able.

168 Full many a dainty horse had he in stable,

169 And when he rode, men might his bridle hear

170 Jingling in a whistling wind all clear

171 And too as loud as doth the chapel bell

172 There as this lord was keeper of the cell.

173 The rule of Saint Maure or of Saint Benedict -

174 Because that it was old and somewhat strict

175 This same monk let old things pass,

176 And held after the new world the space.

177 He gave not of that text a pulled hen,

178 That says that hunters be not holy men,

179 Nor that a monk, when he is reckless,

180 Is likened to a fish that is waterless -

181 This is to say, a monk out of his cloister.

182 But that text held he not worth an oyster;

183 And I said his opinion was good.

184 What should he study and make himself wood,

185 Upon a book in cloister always to pour,

186 Or swink with his hands, and labor,

187 As Austin bid? How shall the world be served?

188 Let Austin have his swink to him reserved!

189 Therefore he was a pricasour aright:

190 Greyhounds he had as swift as fowl in flight;

191 Of pricking and of hunting the hare

192 Was all his lust, for no cost would he spare.

193 I saw his sleeves purfled at the hand

194 With gray, and that the finest of the land;

195 And for to fasten his hood under his chin,

196 He had of gold wrought a full curious pin;

197 A love knot in the greater end there was.

198 His head was bald, that shone as any glass,

199 And too his face, as he had been anoint.

200 He was a lord full fat and in good point;

201 His eyes steep, and rolling in his head,

202 That steamed as a furnace of lead;

203 His boots supple, his horse in great estate.

204 Now certainly he was a fair prelate;

205 He was not pale as a forpined ghost.

206 A fat swan he loved best of any roast.

207 His palfrey was as brown as is a berry.

208 A Friar there was, a wanton and a merry,

209 A limiter, a full solemn man.

210 In all the orders four there is none that can

211 So much of dalliance and fair language.

212 He had made full many a marriage

213 Of young women at his own cost.

214 Unto his order he was a noble post.

215 Full well beloved and familiar was he

216 With franklins over all in his country,

217 And too with worthy women of the town;

218 For he had power of confession,

219 As said himself, more than a curate,

220 For of his order he was licentiate.

221 Full sweetly heard he confession,

222 And pleasant was his absolution:

223 He was an easy man to give penance,

224 There as he knew to have a good pittance.

225 For unto a poor order for to give

226 Is sign that a man is well shrive;

227 For if he gave, he dared make avaunt,

228 He knew that a man was repentant;

229 For many a man so hard is of his heart,

230 He may not weep, although him sorely smart.

231 Therefore instead of weeping and prayers

232 Men must give silver to the poor friars.

233 His tippet was ay farsed full of knives

234 And pins, for to give young wives.

235 And certainly he had a merry note:

236 Well could he sing and play on a rote;

237 Of yeddings he bore utterly the prize.

238 His neck white was as the flour-de-lys;

239 Thereto he strong was as a champion.

240 He knew the taverns well in every town

241 And every hosteler and tappester,

242 Better than a lazar or a begster,

243 For unto such a worthy man as he

244 Accorded not, as by his faculty,

245 To have with sick lazars acquaintance.

246 It is not honest, it may not advance,

247 For to deal with no such porail,

248 But all with rich and sellers of victual.

249 And over all, there as profit should arise,

250 Courteous he was and lowly of service;

251 There’s no man nowhere so virtuous.

252 He was the best beggar in his house;

252a [And gave a certain fee for the grant;

252a None of his brethren came there in his haunt;]

253 For though a widow had not a shoe,

254 So pleasant was his “In principio, ”

255 Yet would he have a farthing, ere he went.

256 His purchase was well better than his rent.

257 And rage he could, as it were right a whelp.

258 In love days there could he much help,

259 For there he was not like a cloisterer

260 With a threadbare cope, as is a poor scholar,

261 But he was like a master or a pope.

262 Of double worsted was his semicope,

263 That rounded as a bell out of the press.

264 Somewhat he lisped, for his wantonness,

265 To make his English sweet upon his tongue;

266 And in his harping, when that he had sung,

267 His eyes twinkled in his head aright

268 As do the stars in the frosty night.

269 This worthy limiter was called Huberd.

270 A merchant was there with a forked beard,

271 In motley, and high on horse he sat;

272 Upon his head a Flanderish beaver hat,

273 His boots clasped fair and featously.

274 His reasons he spoke full solemnly,

275 Speaking always the increase of his winning.

276 He would the sea were kept for anything

277 Between Middleburgh and Orwell.

278 Well could he in exchange shields sell.

279 This worthy man full well his wit beset;

280 There knew no wight that he was in debt,

281 So stately was he of his governance

282 With his bargains and with his chevisance

283 For truth he was a worthy man withall,

284 But, truth to say, I know not how men him call.

285 A clerk there was of Oxford also,

286 That unto logic had long ago.

287 As lean was his horse as is a rake,

288 And he was not right fat, I undertake,

289 But looked hollow, and thereto soberly,

290 Full threadbare was his overest courtepy,

291 For he had gotten him yet no benefice,

292 Nor was so worldly for to have office.

293 For he was rather have at his bed’s head

294 Twenty books, clad in black or red,

295 Of Aristotle and his philosophy

296 Than robes rich, or fiddle, or gay psaltry.

297 But all be that he was a philosopher,

298 Yet had he but little gold in coffer;

299 But all that he might of his friends hent,

300 On books and on learning he it spent,

301 And busily gan for the soul’s prayer

302 Of them that gave him wherewith to scholar.

303 Of study took he most cure and most heed.

304 Not a word spoke he more than was need,

305 And that was said in form and reverence,

306 And short and quick and full of high sentence;

307 Sounding in moral virtue was his speech,

308 And gladly would he learn and gladly teach.

309 A Sergeant of the Law, aware and wise,

310 That often had been at the Parvise,

311 There was also, full rich of excellence.

312 Discreet he was and of great reverence –

313 He seemed such, his words were so wise.

314 Justice he was full often in assize,

315 By patent and by plain commission.

316 For his science and for his high renown,

317 Of fees and robes had he many a one.

318 So great a purchaser was nowhere none:

319 All was fee simple to him in effect;

320 His purchasing might not been infect.

321 Nowhere so busy a man as he there was,

322 And yet he seemed busier than he was.

323 In terms had he case and dooms all

324 That from the time of King William were fall.

325 Thereto he could endite and make a thing,

326 There could no wight pinch at his writing;

327 And every statute could he play by rote.

328 He rode but homely in a motley coat,

329 Girt with a seynt of silk, with bars small;

330 Of his array shall I no longer tell.

331 A Franklin was in his company.

332 White was his beard as is the daisy;

333 Of his complexion he was sanguine.

334 Well loved he by the morning a sup of wine;

335 To live in delight was ever his won,

336 For he was Epicurus’ own son,

337 That held opinion that plain delight

338 Was very felicity parfit.

339 A householder, and that a great, was he;

340 Saint Julian was he in his country.

341 His bread, his ale, was always after one;

342 A better envied man was nowhere known.

343 Without baked meat was never his house,

344 Of fish and flesh, and that so plenteous

345 It snowed in his house of meat and drink;

346 Of all dainties that men could think,

347 After the sundry seasons of the year,

348 So changed he his meat and his supper.

349 Full many a fat partridge had he in mew,

350 And many a bream and many a luce in stew.

351 Woe was his cook but if his sauce were

352 Poignant and sharp, and ready all his gear.

353 His table dormant in his hall alway

354 Stood ready covered all the long day.

355 At sessions there he was lord and sire;

356 Full oft time he was knight of the shire.

357 A dagger and a purse all of silk

358 Hung at his girdle, white as morning milk.

359 A sheriff had he been, an auditor.

360 Was nowhere such a worthy vavasour.

361 A Haberdasher and a Carpenter,

362 A Weaver, a Dyer, and a Tapisser –

363 And they were clothed all in a livery

364 Of a solemn and a great fraternity.

365 Full fresh and new their gear apiked was;

366 Their knives were mounted not with brass

367 But all with silver, wrought full clean and well,

368 Their girdles and their pouches everydell.

369 Well seemed each of them a fair burgess

370 To sit in a guildhall on a dais.

371 Each one, for the wisdom that he kan,

372 Was shapely for to be an alderman.

373 For cattle had they enough and rent,

374 And too their wives would it well assent

375 And else certain were they to blame.

376 It is full fair to have been called “madame, ”

377 And go to vigils all before,

378 And have a mantle royally bore.

379 A Cook they had with them for the nonce

380 To boil the chickens with the marrow bones,

381 And powdered marchant tart and galingale.

382 Well could he know a draft of London ale.

383 He could he roast, and seethe, and broil, and fry,

384 Makemortreux, and well bake a pie.

385 But great harm was it, as it thought me,

386 That on his shin, an ulcer had he.

387 For blancmanger, that made he with the best.

388 A Shipman was there, dwelling far by west;

389 For aught I know, he was of Dartmouth.

390 He rode upon a rouncy, as he couth,

391 In a gown of falding to the knee.

392 A dagger hanging on a laas had he

393 About his neck, under his arm adown.

394 The hot summer had made his hue all brown;

395 And certainly he was a good fellow.

396 Full many a draft of wine had he draw.

397 From Bordeaux-ward, while that the chapman sleep.

398 Of nice conscience took he no keep.

399 If that he fought and had the higher hand,

400 By water he sent them home to every land.

401 But of his craft to reckon well his tides,

402 His streams, and his dangers him besides,

403 His harbor, and his moon, his pilotage,

404 There was none such from Hull to Carthage.

405 Hardy he was and wise to undertake;

406 With many a tempest had his beard been shake.

407 He knew all the havens, as they were,

408 From Gotland to the cape of Finisterre,

409 And every creek in Brittany and in Spain.

410 His barge called was the Madelene.

411 With us there was A Doctor of Physic;

412 In all this world there was no one like him,

413 To speak of physic and of surgery,

414 For he was grounded in astronomy.

415 He kept his patient a full great deal

416 In hours, by his magic natural.

417 Well could he fortune the ascendant

418 Of his images for his patient.

419 He knew the cause of every malady,

420 Were it of hot, or cold, or moist, or dry,

421 And where they engendered, and of what humor.

422 He was a very, perfect practitioner:

423 The cause known, and of his harm the root,

424 Anon he gave the sick man his boot.

425 Full ready had he his apothecaries

426 To send him drugs and electuaries,

427 For each of them made other for to win –

428 Their friendship was not new to begin.

429 Well knew he the old Aesculapius,

430 And Dioscorides and too Rufus,

431 Old Hippocrates, Hali, and Galen,

432 Serapion, Rhazes, and Avicen,

433 Averroes, Damascene, and Constantine,

434 Bernard, and Gatisden, and Gilbertus.

435 Of his diet measurable was he,

436 For it was of no superfluity,

437 But of great nourishing and digestable.

438 His study was but little on the Bible.

439 In sanguine and in perse he clad was all,

440 Lined with taffeta and with sendal.

441 And yet he was but easy of dispense;

442 He kept that he won in pestilence.

443 For gold in physic is a cordial,

444 Therefore he loved gold in special.

445 A good Wife was there of beside Bath,

446 But she was somewhat deaf, and that was scathe.

447 Of cloth making she had such a haunt

448 She passed them of Ypres and of Ghent.

449 In all the parish wife was there none

450 That to the offering before her should go on;

451 And if they did, certain so wroth was she

452 That she was out of all charity.

453 Her coverchiefs full fine were of ground;

454 I dare swear they weighed ten pound

455 That on a Sunday were upon her head.

456 Her hose were of fine scarlet red,

457 Full straight tied, and shoes full moist and new.

458 Bold was her face, and fair, and red of hew.

459 She was a worthy woman all her life:

460 Husbands at church door she had five,

461 Without them other company in youth -

462 But there's no need to speak as now.

463 And thrice had she been at Jerusalem;

464 She had passed many a strange stream;

465 At Rome she had been, and at Boulogne,

466 In Galicia at Saint Jame, and at Cologne.

467 She could much of wandering by the way.

468 Gap-toothed was she, truly for to say.

469 Upon an ambler easily she sat,

470 Wimpled well, and on her head a hat

471 As broad as is a buckler or a targe;

472 A foot-mantle about her hips large,

473 And on her feet a pair of spurs sharp.

474 In fellowship well could she laugh and carp.

475 Of remedies of love she knew per chance,

476 For she knew of that art the old dance.

477 A good man was there of religion,

478 And was a poor Parson of a town,

479 But rich he was of holy thought and work.

480 He was also a learned man, a clerk,

481 That Christ’s Gospel truly would preach;

482 His parishioners devoutly would he teach.

483 Benign he was and wonder diligent,

484 And in adversity full patient,

485 And such he was proved oft times.

486 Full loathe was he to curse for his tithes,

487 But rather would he give, out of doubt,

488 Unto his poor parishioners about

489 Of his offering and too of his substance.

490 He could in little things have sufficience.

491 Wide was his parish, and houses far asunder,

492 But he left not, for rain or thunder,

493 In sickness nor in mischief to visit

494 The farthest in his parish, much and light,

495 Upon his feet, and in his hand a stave.

496 This noble example to his sheep he gave,

497 That first he wrought, and afterward he taught.

498 Out of the Gospel he those words caught,

499 And this figure he added eek thereto,

500 That if gold rust, what shall iron do?

501 For if a priest be foul, on whom we trust,

502 No wonder is a lewd man to rust;

503 And shame it is if a priest take keep,

504 A shitten shepherd and a clean sheep.

505 Well ought a priest example for to give,

506 By his cleanness, how that his sheep should live.

507 He set not his benefice to hire

508 And let his sheep encumbered in the mire

509 And ran to London unto Saint Paul’s

510 To seek him a chantry for souls,

511 Or with a brotherhood to be withhold;

512 But dwelt at home, and kept well his fold,

513 So that the wolf not make it miscarry;

514 He was a shepherd and not a mercenary.

515 And though he holy were and virtuous,

516 He was to sinful men not despitous,

517 Nor of his speech dangerous nor digne,

518 But in his teaching discreet and benign.

519 To draw folk to heaven by fairness,

520 By good example, this was his business.

521 But it were any person obstinate,

522 What so he were of high or low estate,

523 Him would he snib him sharply for the nonce.

524 A better priest I trust that nowhere none is.

525 He waited after no pomp and reverence,

526 Nor maked him a spiced conscience,

527 But Christ’s lore and his apostles twelve

528 He taught; but first he followed it himself.

529 With him there was a Plowman, was his brother,

530 That had hauled of dung full many a fother;

531 A true swinker and a good was he,

532 Living in peace and perfect charity.

533 God loved he best with all his whole heart

534 At all times, though him gamed or smarte,

535 And then his neighbor right as himself.

536 He would thresh, and thereto dike and delve,

537 For Christ’s sake, for every poor wight,

538 Without hire, if it lay in his might.

539 His tithes paid he full fair and well,

540 Both of his proper swink and his chattel.

541 In a tabard he road upon a mare.

542 There was also a Reeve and a Miller,

543 A Summoner and a Pardoner also,

544 A Manciple, and myself, - there were no more.

545 The Miller was a stout carl for the nonce;

546 Full big he was of brawn, and too of bones.

547 That proved well, for over all there he came,

548 At wrestling he would have always the ram.

549 He was short-shouldered, broad, a thick knar;

550 There was no door that he could not heave off har,

551 Or break it at a running with his head.

552 His beard as any sow or fox was red,

553 And thereto broad as it were a spade.

554 Upon the top right of his nose he had

555 A wart, and thereon stood a tuft of hairs,

556 Red as the bristles of a sow’s ears;

557 His nostrils black were and wide.

558 A sword and a buckler bore he by his side.

559 His mouth as great was as a great furnace.

560 He was a jangler and a goliardeys,

561 And that was most of sin and harlotries.

562 Well could he steal corn toll threes;

563 And yet he had a thumb of gold, pardie.

564 A white cope and a blue hood wore he.

565 A bagpipe well could he blow and sound,

566 And therewithal he brought us out of town.

567 A gentle Manciple was there of a temple,

568 Of which achatours might take example

569 For to be wise in buying of victuals;

570 For whether that he paid or took by tally,

571 Always he waited so in his achate,

572 That he was ay before and in good state.

573 Now is not that of God a full fair grace

574 That such a lewd man’s wit shall pace

575 The wisdom of a heap of learned men?

576 Of masters had he more than thrice ten,

577 That were of law expert and curious,

578 Of which there were a dozen in that house

579 Worthy to be stewards of rent and land

580 Of any lord that is in England,

581 To make him live by his proper good

582 In honor debtless (but if he were wood) ,

583 Or live as scarcely as he might desire;

584 And able for to help all a shire

585 In any case that might fall or hap

586 And yet this Manciple set their all cap.

587 The Reeve was a slender choleric man.

588 His beard was shaved as nigh as ever he can;

589 His hair was by his ears full round shorn;

590 His top was docked like a priest before.

591 Full long were his legs and full leen,

592 Like a staff; there was no calf seen.

593 Well could he keep a garner and bin;

594 There was no auditor could on him win.

595 Well wist he by the drought and by the rain

596 The yielding of his seed and of his grain.

597 His lord’s sheep, his neet, his dairy,

598 His swine, his horse, his steer, and his poultry

599 Was wholly in this Reeve’s governing,

600 And by his covenant gave the reckoning,

601 Since that his lord was twenty year of age.

602 There could no man bring him in arrearage.

603 There’s no bailiff, no herder, no other hine,

604 That he not knew his sleight and his covine;

605 They were adread of him as of the death.

606 His dwelling was full fair upon the heath,

607 With green trees shaded was his place.

608 He could better than his lord purchase.

609 Full rich he was astored privily.

610 His lord well could he please subtlely,

611 To give and lend him of his own good,

612 And have a thank, and yet a coat and hood.

613 In youth he had learned a good mister:

614 He was a well good wright, a carpenter.

615 This Reeve sat upon a full good stot

616 That was all pomely grey, and called Scot.

617 A long surcoat of perse upon him hade,

618 And by his side he bore a rusty blade.

619 Of Norfolk was this Reeve of which I tell,

620 Beside a town men call Baldeswell.

621 Tucked he was as is a friar about,

622 And ever he rode the hindmost of our route.

623 A Summoner was there with us in that place

624 That had a fire-red cherubin’s face,

625 For sauceflemed he was, with eyes narrow.

626 As hot he was and lecherous as a sparrow,

627 With scaled brows black, and piled beard.

628 Of his visage children were afeard.

629 There’s no quick-silver, litharge, nor brimstone,

630 Borax, ceruse, nor oil of tarter none,

631 No ointment that would cleanse and bite,

632 That him might help of his whelks white,

633 Nor of the knobs sitting on his cheeks.

634 Well loved he garlic, onions, and eek leeks,

635 And for to drink strong wine, red as blood;

636 Then would he speak and cry as he were wood.

637 And when that he well drunk had the wine,

638 Then would he speak no word but Latin.

639 A few terms had he, two or three,

640 That he had learned out of some decree –

641 No wonder is, he heard it all the day;

642 And too you know well how that a jay

643 Can call out “Walter” as well as can the pope.

644 But whoso could in other things him grope,

645 Then had he spent all his philosophy;

646 Ay “Questio quid juris” would he cry.

647 He was a gentle harlot and a kind;

648 A better fellow should men not find.

649 He would suffer for a quart of wine

650 A good fellow to have his concubine

651 A twelve month, and excuse him at full;

652 Full privily a finch too could he pull.

653 And if he found anywhere a good fellow,

654 He would teach him to have no awe,

655 In such case of the archdeacon’s curse,

656 But if a man’s soul were in his purse;

657 For in his purse he should punished be.

658 “Purse is the archdeacon’s hell, ” said he.

659 But well I know he lied right indeed;

660 Of cursing ought each guilty man him dread,

661 For curse will slay right as absolving save it,

662 And also ware him of a Significavit.

663 In danger had he at his own guise

664 The young girls of the diocese,

665 And knew their counsel, and was all their rede.

666 A garland had he set upon his head,

667 As great as it were for an ale-stake.

668 A buckler had he made him of a cake.

669 With him there rode a gentle Pardoner

670 Of Rouncivale, his friend and his compeer,

671 That straight was come from the court of Rome.

672 Full loud he sang “Come hither, love, to me! ”

673 The Summoner barred to him a stiff burdoun;

674 Was never trumpet of half so great a sound.

675 This Pardoner had hair as yellow as wax,

676 But smooth it hung as does a strike of flax;

677 By ounces hung his locks that he had,

678 And therewith he his shoulders overspread;

679 But thin it lay, by culpons one and one.

680 But hood, for jollity, wore he none,

681 For it was trussed up in his wallet.

682 He thought he rode all of the new jet;

683 Disheveled, save his cap, he rode all bare.

684 Such glaring eyes had he as a hare.

685 A Vernicle had he sowed upon his cap;

686 His wallet, before him in his lap,

687 Bretfull of pardon come from Rome all hot.

688 A voice he had as small as has a goat.

689 No beard had he, nor ever should have;

690 As smooth it was as it were late shave.

691 I trow he were a gelding or a mare.

692 But of his craft, from Berwick into Ware

693 Nor was there such another pardoner.

694 For in his male he had a pillow-bier,

695 Which that he said was Our Lady’s veil;

696 He said he had a gobbet of the sail

697 That Saint Peter had, when that he went

698 Upon the sea, ‘til Jesus Christ him hent.

699 He had a cross of latten full of stones,

700 And in a glass he had pigs’ bones,

701 But with these relics, when that he found

702 A poor person dwelling upon land

703 Upon a day he got him more money

704 Then that the person got in months twey;

705 And thus, with feigned flattery and japes,

706 He made the person and the people his apes.

707 But truly to tell at the last,

708 He was in church a noble ecclesiast.

709 Well could he read a lesson or a story,

710 But all the best he sang an offertory;

711 For well he wist, when that song was sung,

712 He must preach and well affile his tongue

713 To win silver, as he full well could;

714 Therefore he sang the merrily and loud.

715 Now have I told you truly, in a clause,

716 The estate, the array, the number, and too the cause

717 Why that assembled was this company

718 In Southwerk at this gentle hostelry

719 Called the Tabard, fast by the Belle.

720 But now is time to you for to tell

721 How that we baren us that same night,

722 When we were in that hostelry allright;

723 And after will I tell of our voyage

724 And all the remnant of our pilgrimage.

725 But first I pray you, of your courtesy,

726 That you not ascribe it to my villainy,

727 Though that I plainly speak in this matter,

728 To tell you their words and their cheer.

729 Nor though I speak their words properly.

730 For this you know also well as I:

731 Whoso shall tell a tale after a man,

732 He must rehearse as nigh as ever he can

733 Every word, if it be in his charge,

734 All speak he never so rudely or large,

735 Or else he must tell his tale untrue,

736 Or feign things, or find words new.

737 He may not spare, although he were his brother;

738 He might as well say one word as another.

739 Christ spoke himself full broad in holy writ,

740 And well you know no villainy is it.

741 Eek Plato said, whoso can him read,

742 The words must be cousin to the deed.

743 Also I pray you to forgive it me,

744 All have I not set folk in their degree

745 Here in this tale, as that they should stand.

746 My wit is short, you may well understand.

747 Great cheer made our Host us everyone,

748 And to the supper set he us anon.

749 He served us with victuals at the best;

750 Strong was the wine, and well to drink us lest.

751 A seemly man our host was withall

752 For he'd been a marshal in a hall.

753 A large man he was with even step -

754 A fairer burgess was there none in Chepe -

755 Bold of his speech, and wise, and well taught,

756 And of manhood he lacked right naught.

757 Eek thereto he was right a merry man;

758 And after supper playing he began,

759 And spoke of mirth among other things,

760 When that we had made our reckonings,

761 And said thus: "Now, lords, truly,

762 You've been to me right welcome, heartily;

763 For by my troth, if that I shall not lie,

764 I saw not this year so merry a company

765 At once in this herber as is now.

766 Fain would I do you mirth, knew I how.

767 And of a mirth I am right now bethought,

768 To do you ease, and it shall cost naught.

769 "You're going to Canterbury - God you speed,

770 The blissful martyr quit you your meed!

771 And well I know, as you go on by the way,

772 You'll shape you to tell and to play;

773 For truly, comfort nor mirth is none

774 To ride by the way dumb as a stone;

775 And therefore will I make you disport,

776 As I said erst, and do you some comfort.

777 And if you like all by one assent

778 For to stand at my judgment,

779 And for to work, as I shall you say,

780 Tomorrow, when you ride by the way,

781 Now by my father's soul that is dead,

782 But you be merry, I will give you my head!

783 Hold up your hands, without more speech."

784 Our counsel was not long for to seek.

785 We thought it was not worth to make it wise,

786 And granted him without more avise,

787 And bade him say his verdict as he lest.

788 "Lords," said he, "now hearken for the best;

789 But take it not, I pray you, in disdain.

790 This is the point, to speak short and plain,

791 That each of you, to short with our way,

792 In this voyage shall tell tales tway

793 To Canterbury-ward, I mean it so,

794 And homeward he shall tell another two,

795 Of adventures that awhile have befall.

796 And which of you that bears him best of all -

797 That is to say, that tells in this case

798 Tales of best sentence and most solace -

799 Shall have a supper at all our cost

800 Here in this place, sitting by this post,

801 When that we come again from Canterbury.

802 And for to make you the more merry,

803 I will myself goodly with you ride,

804 Right at my own cost, and be your guide;

805 And whoso will my judgment gainsay

806 Shall pay all that we spend by the way.

807 And if you vouchsafe that it be so,

808 Tell me anon, without words more,

809 And I will early shape me therefore."

810 This thing was granted, and our oaths swore

811 With full glad heart, and prayed him also

812 That he would vouchsafe for to do so,

813 And that he would be our governor,

814 And our tale’s judge and reporter,

815 And set a supper at a certain price,

816 And we will ruled be at his devise

817 In high and low; and thus by one assent

818 We were accorded to his judgment.

819 And thereupon the wine was fetched anon;

820 We drank, and to rest went each one,

821 Without any longer tarrying.

822 At morning, when that day began to spring,

823 Up rose our Host, and was all our cock,

824 And gathered us together all in a flock,

825 And forth we rode a little more than pace

826 Unto the watering of Saint Thomas;

827 And there our Host began his horse to rest

828 And said, "Lords, hearken, if you lest,

829 You know your forward, and I it you record.

830 If even-song and morning-song accord,

831 Let's see now who shall tell the first tale.

832 As ever must I drink wine or ale,

833 Whoso be rebel to my judgment

834 Shall pay for all that by the way is spent.

835 Now draw cut, er we further twin;

836 He which that has the shortest will begin.

837 "Sir Knight, " said he, "my master and my lord,

838 Now draw cut, for that is my accord.

839 "Come near, " said he, "my lady Prioress.

840 And you, sir Clerk, let be your shamefacedness,

841 Study it not; lay hand to, every man! "

842 Anon to draw every wight began,

843 And shortly for to tell it as it was,

844 Were it by adventure, or sort, or case,

845 The truth is this: the cut fell to the Knight,

846 Of which full blithe and glad was every wight,

847 And tell he must his tale, as was reason,

848 By forward and by composition,

849 As you have heard; what need words more?

850 And when this good man saw that it was so,

851 And he that wise was and obedient

852 To keep his forward by his free assent,

853 He said, "Since I shall begin the game,

854 What, welcome be the cut, by God's name!

855 Now let us ride, and hearken what I say."

856 And with that word we rode on forth our way,

857 And he began with right a merry cheer

858 His tale anon, and said as you may hear.

© 2008, 2012, 2019 Forrest Hainline

0 notes

Photo

People that have married in to Royal Families since 1800

Belgium

Mary Lilian Baels

Princess Lilian of Belgium better known as Lilian, Princess of Réthy, was the second wife of King Leopold III of the Belgians.

Mary Lilian Baels was born in London, England, where her parents were living at the time. She was one of the nine children of Henri Baels and his wife, Anne Marie de Visscher. Lilian was initially educated in English, but, upon her parents' return to Belgium, she attended a school in Ostend, where she learned Dutch.

She continued her studies in French in Brussels. She completed her education by attending a finishing school in London, the Holy Child. In addition to academic work, Lilian participated extensively in sports, such as skiing, swimming, golfing, and hunting. Above all, however, she enjoyed, as did her father, literature and the arts.

As a teenager, she was presented to King George V and Queen Mary of the United Kingdom at Buckingham Palace

In 1933, Lilian saw her future husband, King Leopold III of the Belgians, then still Duke of Brabant, for the first time during a military review. A few years later, when her father, then Governor of West Flanders, took his daughter to a public ceremony, she had the occasion to meet King Leopold, who presided at the event, for the second time. In 1937, Lilian and her mother met the King, now a widower, again on another ceremonial occasion. Soon afterwards, King Leopold III contacted Governor Baels to invite he and his daughter to join him in a golfing party the next day. Lilian also saw the King in 1939 at a garden-party organised in honour of Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands, and later at the golf course at Laeken, where she was invited to lunch by Queen Elisabeth of Belgium, King Leopold's mother. A final golf party near the Belgian coast occurred in May 1940, shortly before the Nazi invasion of Belgium.

In 1941, at the invitation of Queen Mother Elisabeth, Lilian visited Laeken Castle, where King Leopold III, now a prisoner of war, was held by the Germans under house arrest. This visit was followed by several others, with the result that Leopold III and Lilian fell in love. Leopold proposed marriage to Lilian in July 1941, but Lilian declined his offer. "Kings only marry princesses," she said. Queen Elisabeth, however, prevailed upon Lilian to accept the King's offer. Lilian agreed to marry the King, but declined the title of Queen. Instead, the King gave her the unofficial title "Princess of Réthy." It was agreed that any descendants of the King's new marriage would be excluded from succession to the throne. Leopold and Lilian initially planned to hold their official, civil marriage after the end of the war and the liberation of Belgium, but in the meantime, a secret religious marriage ceremony took place on 11 September 1941, in the chapel of Laeken Castle Although Lilian and Leopold had originally planned to postpone their civil marriage until the end of the war, Lilian was soon expecting her first child, necessitating a civil marriage, which took place on 6 December 1941.

Lilian proved a devoted wife to the King and an affectionate and vivacious mother to his children by his first wife, Queen Astrid. When the civil marriage of Leopold and Lilian was made public in a pastoral letter by Cardinal van Roey read throughout Belgian churches in December 1941, there was a mixed reaction in Belgium. Some showed sympathy for the new couple, sending flowers and messages of congratulations to the palace at Laeken Others, however, argued that the marriage was incompatible with the King's status as a prisoner-of-war and his stated desire to share the hard fate of his conquered people and captive army, and was a betrayal of Queen Astrid's memory. They also branded Lilian as a social-climber. Leopold and Lilian were also blamed for violating Belgian law by holding their religious marriage before their civil one. These criticisms would continue for many years, even after the war. Queen Astrid's parents, the Duke and Duchess of Västergötland, did not take the hard line against King Leopold's remarriage. Princess Ingeborg told a Belgian journalist that she couldn't understand all the animus in Belgium against the king's second marriage, that it was perfectly natural for a young man not to want to remain alone forever. She said she was happy about her former son-in-law's new marriage, both for his own sake and for the sake of her grandchildren.

In 1944, the Belgian royal family was deported to Nazi Germany, where they were strictly guarded by 70 members of the SS, under harsh conditions. The family suffered from a deficient diet and lived with the constant fear that they would be massacred by their jailers, as an act of revenge on the part of the Nazis, angered at their defeat (by now becoming increasingly certain) by the Allies, or that they would be caught in the cross-fire between Allied forces and their captors, who might try to make a desperate last stand at the site of the royal family's internment. The family's fears were not unfounded. At one point, a Nazi official tried to give them cyanide, pretending it was a mixture of vitamins to compensate for the captives' poor diet during their imprisonment. Lilian and Leopold, however, were rightly suspicious and did not take the pills or give them to their children. During their period of captivity in Germany, (and later Austria), Leopold and Lilian jointly homeschooled the royal children. The King taught scientific subjects; his wife, arts and literature. In 1945, the Belgian royal family was liberated by American troops under the command of Lieutenant General Alexander Patch, who thereafter became a close friend of King Leopold and Princess Lilian.

Following his liberation, King Leopold was unable to return to Belgium (by now liberated as well) due to a political controversy that arose in Belgium surrounding his actions during World War II. He was accused of having betrayed the Allies by an allegedly premature surrender in 1940 and of collaborating with the Nazis during the occupation of Belgium. In 1946, a juridical commission was constituted in Brussels to investigate the King's conduct during the war and occupation. During this period, the king and his family lived in exile in Pregny-Chambésy, Switzerland, and the King's younger brother, Prince Charles, Count of Flanders, was made regent of the country. The commission of inquiry eventually exonerated Leopold of the charges and he was able, in 1950, to return to Belgium and resume his reign.

Political agitation against the King continued, however, leading to civil disturbances in what became known as the Royal Question. As a result, in 1951, to avoid tearing the country apart and to save the embattled monarchy, King Leopold III of the Belgians abdicated in favour of his 21-year-old son, Prince Baudouin. In the first nine years reign of her stepson, King Baudouin, Lilian acted as First Lady of Belgium and manages the life of the Court with firmness and refinement, but she never be loved by the Belgians. The ex-King Leopold and Princess Lilian continued to live in the royal palace at Laeken until the marriage of Baudouin to Doña Fabiola de Mora y Aragón in 1960.

In 1960, following the marriage of King Baudouin, Leopold and Lilian moved out of the royal palace to a government property, the estate of Argenteuil, Belgium. Lilian employed various designers to transform the dilapidated mansion on the property into a distinguished and elegant residence for the ex-King. Argenteuil became a cultural centre under the auspices of Leopold and Lilian, who cultivated the friendship of numerous prominent writers, scientists, mathematicians, and doctors. Leopold and Lilian also travelled extensively all over the world.

Following her son Alexandre's heart surgery in the United States during his childhood, Princess Lilian became very interested in medicine, and, in particular, in cardiology, and founded a Cardiological Foundation which, through its work, has saved the lives of hundreds of people.

Both before and after her husband's death in 1983, Lilian pursued her interests in intellectual and scientific spheres with energy and passion

Lilian was known as a woman who was terribly strict and demanding towards herself, and, a result, as one who could be excessively severe with others as well. Due to the controversy surrounding King Leopold's wartime actions, and, in particular, his second marriage, Lilian was widely unpopular in Belgium. She also, however, had a circle of close friends, who saw her as a woman of great beauty, charm, intelligence, elegance, strength of character, kindness, generosity, humor and culture. They admired her for the courage and dignity with which she faced a long series of personal attacks, both during the Royal Question and for decades afterwards

Princess Lilian died at the Domaine d'Argenteuil in Waterloo, Belgium. Before her death, she had expressed the desire to be buried at Argenteuil. Her wish was denied, however, and she was buried in the royal crypt of the Church of Our Lady, Laeken, Belgium, with King Leopold and his first wife, Queen Astrid.

Queen Fabiola and Lilian's stepchildren attended the funeral, as did Lilian's son Alexandre and her daughter Marie-Esmeralda. Lilian's long-estranged daughter Marie-Christine did not attend. Following Princess Lilian's death, a cardiological conference was organised and prominent doctors and surgeons such as DeBakey and many others rendered an homage to Lilian and her contributions to cardiology.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

People that have married in to Royal Families since 1800

Belgium

Mary Lilian Baels

Princess Lilian of Belgium better known as Lilian, Princess of Réthy, was the second wife of King Leopold III of the Belgians.

Mary Lilian Baels was born in London, England, where her parents were living at the time. She was one of the nine children of Henri Baels and his wife, Anne Marie de Visscher. Lilian was initially educated in English, but, upon her parents' return to Belgium, she attended a school in Ostend, where she learned Dutch.

She continued her studies in French in Brussels. She completed her education by attending a finishing school in London, the Holy Child. In addition to academic work, Lilian participated extensively in sports, such as skiing, swimming, golfing, and hunting. Above all, however, she enjoyed, as did her father, literature and the arts.

As a teenager, she was presented to King George V and Queen Mary of the United Kingdom at Buckingham Palace

In 1933, Lilian saw her future husband, King Leopold III of the Belgians, then still Duke of Brabant, for the first time during a military review. A few years later, when her father, then Governor of West Flanders, took his daughter to a public ceremony, she had the occasion to meet King Leopold, who presided at the event, for the second time. In 1937, Lilian and her mother met the King, now a widower, again on another ceremonial occasion. Soon afterwards, King Leopold III contacted Governor Baels to invite he and his daughter to join him in a golfing party the next day. Lilian also saw the King in 1939 at a garden-party organised in honour of Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands, and later at the golf course at Laeken, where she was invited to lunch by Queen Elisabeth of Belgium, King Leopold's mother. A final golf party near the Belgian coast occurred in May 1940, shortly before the Nazi invasion of Belgium.

In 1941, at the invitation of Queen Mother Elisabeth, Lilian visited Laeken Castle, where King Leopold III, now a prisoner of war, was held by the Germans under house arrest. This visit was followed by several others, with the result that Leopold III and Lilian fell in love. Leopold proposed marriage to Lilian in July 1941, but Lilian declined his offer. "Kings only marry princesses," she said. Queen Elisabeth, however, prevailed upon Lilian to accept the King's offer. Lilian agreed to marry the King, but declined the title of Queen. Instead, the King gave her the unofficial title "Princess of Réthy." It was agreed that any descendants of the King's new marriage would be excluded from succession to the throne. Leopold and Lilian initially planned to hold their official, civil marriage after the end of the war and the liberation of Belgium, but in the meantime, a secret religious marriage ceremony took place on 11 September 1941, in the chapel of Laeken Castle Although Lilian and Leopold had originally planned to postpone their civil marriage until the end of the war, Lilian was soon expecting her first child, necessitating a civil marriage, which took place on 6 December 1941.

Lilian proved a devoted wife to the King and an affectionate and vivacious mother to his children by his first wife, Queen Astrid. When the civil marriage of Leopold and Lilian was made public in a pastoral letter by Cardinal van Roey read throughout Belgian churches in December 1941, there was a mixed reaction in Belgium. Some showed sympathy for the new couple, sending flowers and messages of congratulations to the palace at Laeken Others, however, argued that the marriage was incompatible with the King's status as a prisoner-of-war and his stated desire to share the hard fate of his conquered people and captive army, and was a betrayal of Queen Astrid's memory. They also branded Lilian as a social-climber. Leopold and Lilian were also blamed for violating Belgian law by holding their religious marriage before their civil one. These criticisms would continue for many years, even after the war. Queen Astrid's parents, the Duke and Duchess of Västergötland, did not take the hard line against King Leopold's remarriage. Princess Ingeborg told a Belgian journalist that she couldn't understand all the animus in Belgium against the king's second marriage, that it was perfectly natural for a young man not to want to remain alone forever. She said she was happy about her former son-in-law's new marriage, both for his own sake and for the sake of her grandchildren.

In 1944, the Belgian royal family was deported to Nazi Germany, where they were strictly guarded by 70 members of the SS, under harsh conditions. The family suffered from a deficient diet and lived with the constant fear that they would be massacred by their jailers, as an act of revenge on the part of the Nazis, angered at their defeat (by now becoming increasingly certain) by the Allies, or that they would be caught in the cross-fire between Allied forces and their captors, who might try to make a desperate last stand at the site of the royal family's internment. The family's fears were not unfounded. At one point, a Nazi official tried to give them cyanide, pretending it was a mixture of vitamins to compensate for the captives' poor diet during their imprisonment. Lilian and Leopold, however, were rightly suspicious and did not take the pills or give them to their children. During their period of captivity in Germany, (and later Austria), Leopold and Lilian jointly homeschooled the royal children. The King taught scientific subjects; his wife, arts and literature. In 1945, the Belgian royal family was liberated by American troops under the command of Lieutenant General Alexander Patch, who thereafter became a close friend of King Leopold and Princess Lilian.

Following his liberation, King Leopold was unable to return to Belgium (by now liberated as well) due to a political controversy that arose in Belgium surrounding his actions during World War II. He was accused of having betrayed the Allies by an allegedly premature surrender in 1940 and of collaborating with the Nazis during the occupation of Belgium. In 1946, a juridical commission was constituted in Brussels to investigate the King's conduct during the war and occupation. During this period, the king and his family lived in exile in Pregny-Chambésy, Switzerland, and the King's younger brother, Prince Charles, Count of Flanders, was made regent of the country. The commission of inquiry eventually exonerated Leopold of the charges and he was able, in 1950, to return to Belgium and resume his reign.