#i might draw either him or fantine next

Text

She's too cute

#im on episode 5already 😭#my art#shoujo cosette#eponine#les mis#artists on tumblr#art#sketches#fanart#jean valjeans voice in arabic is so good#i can't wait for when cosette and jean meet#i might draw either him or fantine next#azelma copying eponines words is so cute i might cry#even if she's a bad influence#i love her tho#the sound in this show is so nice

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brick Club 1.3.9 “Joyful End Of Joy”

This title is such a weird choice. This time it’s not a translation thing, but a Hugo thing. He decides not to focus on Fantine’s reaction to the surprise, but on the other girls’ reactions. It’s weird, but I think it also works, because it serves to highlight how unusual Fantine’s reaction really is. The rest of the girls shake off the abandonment pretty quickly, because none of them made the same attachments as Fantine. Her devastation is highlighted by their mirth.

The men keep up the pretense long enough to even turn and wave at the women, laughing. I get the impression they’re giggling at their prank, but the girls probably think they’re just being jaunty. Also, I wish I had a better visual of the area. I imagine them kind of blending in with the crowd, maybe turning a corner or something out of sight, and then heading to wait for the stagecoach.

Again, Hugo shows the difference between Fantine and the others. While Fantine repeats herself with “Don’t be long,” the other grisettes are more preoccupied with what the surprise might be. Also, so far Fantine’s really only had two lines, since one was about the horse, and the next two lines are nearly identical to each other.

“You’d think piles of chains were flying off into the heavens.” I love the visual of this line so much. There are so many visuals in this book that I wish I had the skill to draw. This line’s an interesting one. My first instinct is to say that the metaphor feels backwards? “Piles of chains flying off into the heavens” sounds to me like saying these men that could have held these women down are leaving. But that seems backward. Unless perhaps that’s the opinion of the other grisettes aside from Fantine? My other thought is that maybe it’s not really a good thing or a backward metaphor. These chains which are the men are flying off, but the next ones could be even worse, could leave the rest of them in the type of situation that Fantine is now left in. These specific chains have flown off into the heavens, but that doesn’t mean there aren’t more waiting in the wings.

The fact that Fantine gets the most important, foreshadowing line is interesting to me because it’s a very specific observation. “That’s strange,” she said. “I thought the stagecoaches never stopped.” The group has just spent the last 8 chapters mocking Fantine’s head-in-the-clouds state of being and how she doesn’t notice anything. And yet she notices this little detail and points out that the stagecoaches don’t usually stop. (I like this from the headcanon that she’s autistic, too. Social cues etc are harder to pick up on, but a change in a weird little detail like when the stagecoaches stop is something she notices because it’s wrong but no one else notices or cares.)

Favourite then insults Fantine and says she knows nothing of life and essentially calls her a simpleton while making fun of her observation. What is Favourite’s problem? She’s really the only one aside from Tholomyes who gets actual dialogue mocking Fantine. God, this whole group is so awful. The next line is “Some time passed this way.” I can’t tell if Hugo is saying that some time passed where they were just staring out the window, or if he’s saying some time passed where they were making fun of Fantine. Either way, this constant picking on Fantine is so cruel, from all of them. Especially Favourite and Tholomyes. It seems like Favourite is in the best situation out of all of them, too: she’s the eldest, has her own home, and is cheating on Blacheville with Tholomyes. Maybe she’s guilty and that’s why she’s so aggressive towards Fantine; she’s trying to convince herself there’s a reason she’s doing this thing with Tholomyes. I don’t know.

It seems like Fantine has never really had stable friendships in her life. These girls have been having affairs with the students for two years. It might be the longest Fantine has every really had a friendly, familiar, consistent relationship with other grisettes outside of work. And it seems like the other grisettes, particularly Favourite, really take advantage of that naivety to mock her.

Why is Favourite the only one so preoccupied with the surprise? She was the one to ask for it properly, to announce it the morning of and get everyone up early, to keep reminding everyone of it, and now to read the letter. Nobody else seems to be as obsessed with the surprise as her. No one else has dialogue mentioning it. She’s like the “leader” of this little group, so it stands to reason that she’s Tholomyes’ counterpart and that would make her be the one who thinks about the surprise kind of in tandem with the fact that Tholomyes is the one orchestrating it. But I still think it’s odd that nobody else seems to care as much as she does. It almost sounds like an insecurity, a point of anxiety for her? Everyone but Fantine seems to be expecting Gifts. I actually wonder now if this is why they are unsurprised by the letter being a parting one. What they think is going to happen is that they are going to get parting gifts; instead they get this letter and a paid for meal. It’s a letdown, but the leaving is expected, I think.

Before I get into the letter, I just want to point out how weirdly classical the line “they desire our return and offer to kill the fatted calf for us” is. The rest of the letter just sounds like a regular letter, but that line in particular sounds like I’m reading Homer or something.

The men start off their letter explicitly pointing out the class differences between the themselves and the grisettes. Despite the fact that Favourite’s mother lives with her, the men obviously don’t see that as similar to their own, rich parents. Hugo says earlier that Fantine is, essentially, a child of France. The students seem to see all of the women in that way, as crude orphans who have been taken in and socialized by Paris. The men then contradict themselves, quoting their parents as calling them “prodigal sons” and then in the next sentence calling themselves “virtuous.”

I can’t find anything on the Bossuet line; I assume it’s a pun that I don’t know enough French and/or Bossuet literature to understand. “Fleeing to the arms of Laffitte,” I assume, means running back to high society, back to rich families and political connections and all that stuff. They’re no longer slumming in Paris with working girls, they’re going back to the safety of the society of banking and politics and all that. I don’t know what the “wings of Caillard” is referencing, because the only Caillard I can find is Gaspar Caillard, whose writings aren’t translated into English.

The gall of them to straight up call the girls “the abyss,” man I hate these men. They see these women as a fun little jaunt into lower society. These women, who are without family (or the same kind of family as these men), who are very poor and probably teetering on the edge of penniless, are the closest these students can get to this “abyss.” I bet they think they did some sort of fucking charity, too, and treated these girls to a “good time” for two years or something before dropping them. Ugh.

“It is necessary to our country that we become, like everybody else, prefects, fathers of families, country policemen, and councilors of state.” Reading this line just makes me feel so disgusted. That men like this, who are slimy and manipulative and selfish and uncaring like this, are the ones who are going to become people in charge of the infrastructure of their local society and who will have power over people in similar positions to these grisettes. It reminds me of Bamatabois, who not only was able to harass Fantine and then get her nearly thrown in prison, but was also a juror at Chapmathieu’s trial. Twice he has the power to decide someone’s freedom; I imagine these law students will have similar positions in their own respective towns. It’s also such a gross flaunting of their social position, telling these women that they have all these opportunities and connections and money to become whatever they want, and these women are left in barely-paying labor positions on the edge of total poverty.

(This is also a really important piece of characterization, I think. It contrasts massively with the students we see later on, who come from rich families (minus Bahorel, I suppose) but who are dedicated to the betterment of others.)

Something I don’t quite understand is the paying for dinner thing? Why? Is it just because they knew maybe the girls wouldn’t be able to afford it? Why do that one niceness with such a cruel prank? Was it like a last “look at us, we can afford one last lavish meal before we vanish” sort of thing?

Favourite is so odd to me. She decides that if this prank was Blacheville’s idea, it makes her fall in love with him. She says “No sooner loved than left,” which makes me think it’s a sort of “you don’t want it until it’s gone” type of thing. But I’m also wondering if it’s a comment on potential cleverness. She only likes him more now that she thinks he’s clever enough and cunning enough to come up with and pull off a joke like this one.

Then the realization that it was actually Tholomyes comes. None of them seem surprised (neither are we). They laugh about it and I assume that, again, the “Vive Tholomyes” is a celebration of his cleverness at this elaborate joke. But they seemed to know that the end was coming, so it’s just a funny and interesting ending to them, rather than a boring goodbye. Also, I wonder if they would have been more upset if the dinner had not been paid for.

I don’t have much to say about that last visual of Fantine crying in her rooms, except for fuck Tholomyes. Also, what a damn bombshell for Hugo to drop on us, spending all that time describing Fantine and then in the last sentence revealing a child.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brick Club 4.6.1, 4.6.2

Mme. Thenardier “had disembarrassed herself” of her two youngest boys, which is a fancy way of saying ‘got rid of.’ “Her hatred of the human race began with her boys.” I’d say it’s more like she hates her husband which becomes a hatred of anything that reminds her of him. Her daughters are distanced by merit of gender, but her sons are not so lucky. It’s twisted, but I can understand the psychology that led her to this. Now I’m spinning an entire alternate story where Cosette was born a boy and what that might look like. I have no doubt Fantine wouldn’t act differently either way, but so much of Cosette’s story relies heavily on her characterization as a sweet, innocent young girl.

Magnon pops back up again, she’s an underrated recurring character. She loses her two boys, which is a shame because “these children were precious to their mother; they represented eighty francs a month…the children dead, the income was buried.” Luckily, it really is a buyers market on children in early 19th century France, and the Thenardiers are like 3/4ths of that market.

“At a certain depth of misery, men are possessed by a sort of spectral indifference.” Pssst, it’s alienation. You already know it. Gotta rep my brand.

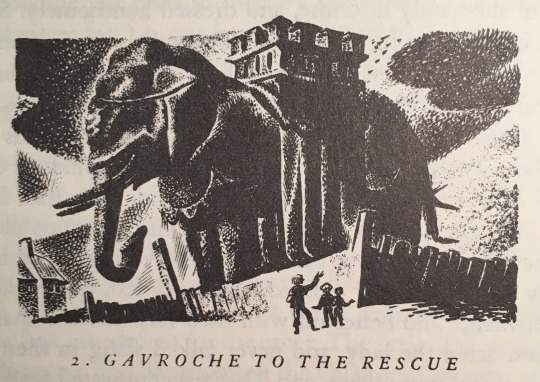

Another utterly gorgeous illustration paired with a mind-bogglingly bad chapter title translation. I’ve got “In Which Little Gavroche Takes Advantage of Napoleon the Great.” Please, Wraxall, why are you doing this?

People are, wow, consistently really awful to children in clear and desperate need in this book. It falls to Gavroche to be the only helpful adult adjacent figure in all of Paris, “and the two children followed him as they would have followed an archbishop.” Some highlights from the Gavroche variety show:

“The bureau is closed, I receive no more complaints.”

“It rains again! Good God, if this continues, I withdraw my subscription.”

“Ah! we have lost our authors. We don’t know now what we have done with them.”

I really like the translation conundrum of Gavroche’s text-language speech. Wilbour translates “Keksekça?” as “Whossachuav?” whereas Hapgood and Wraxall don’t bother to translate it at all. Leaving the original text is probably the right call but I enjoy the linguistic gymnastics of trying to translate and also explain the joke. Weirdly, Hapgood translates all the argot to English while Wilbour leaves it in French.

“All three placed end to end would hardly have made a fathom.” God, that’s kind of the most adorable thing ever. Please someone draw the three Thenardier boys stacked on top of each other wearing a trench coat and still being comically shorter than Montparnasse.

Gavorche and Montparnasse conduct quite the amiable conversation. Their dynamic is pretty interesting, and not what I would expect just from knowing their characters. Montparnasse seems to take Gavroche quite seriously and might even be impressed at some of his remarks. We know Gavroche isn’t so endeared with Montparnasse as to not rob him, and that he’s comfortable enough with the murderer to insult his vanity.

Ok, I want to talk about the elephant, which is a goldmine of symbolism, both for Hugo writing and for us reading. On the first level, the elephant is emblematic of the crumbling of Napoleon’s empire, left to be forgotten and eroded away over time, rats swarming all through the inner workings. “It partook, to some extent of a filth soon to be swept away, and, to some extent, of a majesty soon to be decapitated.” It also represents the transition from empire to, if not a republic, something more domestic, “leaving a peaceable reign to the kind of gigantic stove, adorned with its stove-pipe, which has taken the place of the forbidding nine-towered fortress.” This replacement, and the replacing of feudalist lords with the bourgeoisie is framed as the violent and barbarous past softening into a more civilized society. Although, there is still discontent running fiercely below the domestic facade, “an epoch of which a tea-kettle contains the power.” There is underestimated power in what seems unremarkable. Gavroche uses the elephant to save these two lost boys, when no one else would even let them in their shop.

This takes us neatly into the next layer of symbolism, the disparate utility of the elephant. The elephant is isolated, an eyesore, disdained by the bourgeoisie for being useless. But by falling to this ruin, this “colossal beggar…had taken pity itself on this other beggar, the poor pigmy.” The elephant finds itself on the level of the poor and, in turn, provides for them, just as Gavroche, despite having nothing, provides for those he comes across. Napoleon sought to immortalize his greatness, “he desired to incarnate the people. God had done a grander thing with it, he lodged a child.” This calls all the way back to literally 1.1.1 when Bienvenu tells Napoleon, “You behold a good man, and I a great man.” The bourgeoisie have no use for goodness, they can no longer comprehend the utility of the most basic needs, they only think about usefulness in terms of abstract ideas of greatness. For the gamin who doesn’t have a home or food, the world looks very different; Gavroche doesn’t care about the symbolic might of Napoleon, he cares that the elephant has a roof.

Having said this, I want to take care not to deify the idea of the elephant. It’s easy to get caught up in Hugo’s words here, “This idea of Napoleon…had been taken up by God,” but this is like those “heartwarming” news stories in which a kid sells lemonade to pay for their parent’s medical procedures. Our ire shouldn’t be that the bourgeoisie are so ignorant as to find the elephant useless, it should be that the gamins are in such a desperate situation that they look at a rotting frame of plaster and wood and think “home.”

Related, this is probably why Gavroche is so tough on these kids, while also being incredibly generous. He knows it’s best to get them to adjust quickly to this life, but that doesn’t mean throwing them to the wolves. It’s really painful to watch him have to do this.

#brickclub#les mis#les miserables#4.6.1#4.6.2#gavroche is the absolute best hashtag relatable hashtag mood#it sucks that hes the closest any gamin can have to a parental figure when hes just a kid himself#esp after watching the idyllic relationship between valjean and cosette#anyways gotta love that elephant#that plaster embodiment of just how bullshit the politics of the past 50 years have been

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

How I picture the characters of “Les Mis”

This meme made me decide to write out my mental images of what all the main characters look like. Most of them are vague, based on a blend of Hugo’s descriptions and stage casting traditions. None of them are based on the movie cast, which has made it feel strange in the last several years to see most fan drawings of the characters become movie-based.

I hope other people will see this and share their images of the characters too. I’d love to read them, especially if they’re very different from mine.

Jean Valjean

Medium hight, barrel chested and bulky – not overweight, but more “big-boned” than “ripped.” At most the same height as Javert, more likely shorter, but heavier and more strongly built. Straight, longish, light brown/later white hair and a beard. (Yes, the Brick implies that he gets rid of the beard after breaking parole, but the musical’s stage history makes me picture it throughout.) Eyes either hazel or blue. A roundish face with solid, homely features (not ugly in the least, just completely ordinary) and a reserved expression. If you passed him on the street you’d be struck by his bulk, and by the stark whiteness of his hair in his later years, but he’s far from a Hugh Jackman-style eye-catcher; just a big, strong, average older man.

Javert

Tall, strongly built and imposing, as per Hugo, though more slender and less powerful than Valjean. Rigid posture. Dusky skin, in keeping with his Romani heritage. Dark brown hair; short in the Brick-verse, but musical-Javert has the long, elegant ponytail of stage tradition, regardless of anachronism. Huge forest-like sideburns, as per both Hugo and stage tradition. Brown eyes. A longish, rectangular face with a big square jaw, a snub nose as per Hugo (though less cartoonishly snub than Emile Bayard drew it) and a severe, dignified expression. The rare occasions when he smiles or laughs are, as Hugo tells us, terrifying.

Fantine

Medium height and slender. Long, luxuriant, sunny blonde hair, either wavy or curly; later messily chopped and extremely short. Bright blue eyes. Strikingly beautiful, with a slender face (though I can imagine a roundish one too, at least before she gets sick and loses weight), pale skin, a small straight nose, high cheekbones, and as per Hugo, pretty white teeth. A very classical, dignified type of beauty (as opposed to cuteness or, God forbid, sexiness), influenced in my mind both by Hugo’s references to Greco-Roman goddesses when describing her and by Ruthie Henshall’s look in the TAC. Though of course by the end of her arc, it all turns to emaciated, ashy ghostliness.

Cosette

At 16/17: Medium height and slender. A soft, roundish face like Raphael’s Madonnas, as per Hugo. Medium chestnut brown hair, worn in long ringlets. (Yes, I know she would have more likely sported a curled up-do, but decades of stage tradition have left their mark on my mind.) Bright blue eyes like her mother’s. A small cute nose – probably aquiline, given Hugo’s “Parisian” description, though I don’t always picture it as such. Innocently beautiful, in a way that blends her mother’s natural dignity with girl-next-door cuteness.

As a little girl: See Bayard’s iconic illustration. Just color the hair brown. (Though I’m also open to it being blonde at first, but darkening when she hits puberty, as sometimes happens.)

Marius

Medium height and slender. Boyishly handsome with rounded facial features, as per Hugo, and of course with “wide, passionate nostrils.” Pale skin, with no freckles (sorry, Eddie). Short hair, which I almost always picture as thick, curly and jet black, as per Hugo – though sometimes when I’m thinking only of the musical, I picture it straight and brown instead, or occasionally even blond. Brown eyes are my default image, though I’m open to blue too. As per Hugo, a generally reserved, serious expression, but with a wide, adorable smile when he’s happy; since musical-Marius is warmer and more outgoing than Hugo’s, I imagine that smile appearing more often from him.

Thénardier

Short, scrawny and bony, as per Hugo, though I’m open to picturing musical-Thénardier as slightly taller and/or more solidly built. Longish, stringy brown/later gray hair. No clear idea of eye color: probably either brown, green, or pale blue. A thin, angular face with a wide mouth, a sharp nose and bad teeth; I’m prone to picturing his nose as prominent, but I know that’s a cliché for greedy characters based in hateful Jewish and Romani stereotypes, so sometimes I force myself to imagine it smaller. Brick-Thénardier grows a long, scraggly beard in poverty, as per Hugo; musical-Thénardier just has a permanent five o’ clock shadow.

Mme. Thénardier

Huge and intimidating, as per Hugo. Obese, tall (taller than her husband in the Brick, though musical-Mme. T. might be the same height or slightly shorter), frumpy and masculine looking. Thick, wavy cascades of red/later graying hair. Blotchy skin, as per Hugo. Big, walnut-smashing, child-punching fists. A big face, either squarish or round (Hugo’s description of her as both “fat” and “angular” is hard to imagine, so my brain often defaults to the roundness of most stage actresses), with a snub nose and small, piggy blue eyes. As per Hugo, Brick-Mme. T. has a few chin hairs and a protruding lower tooth, but I don’t picture those details in the musical.

Éponine

Tallish and very thin. Light to medium chestnut brown hair (lighter and more reddish than Cosette’s), naturally straight but stringy with filth. (This is fluid, though – now and then I picture her with dirty strawberry blonde hair instead, or with thick, wild dark curls). Eyes either blue or green. Tanned skin and maybe some freckles. Bony, angular features with a fairly strong nose and wide mouth like her father’s, though musical-Éponine’s face is softer. Brick-Éponine has all the ugly marks of poverty Hugo describes: wasted figure, missing teeth, bleary eyes, etc. Musical-Éponine is prettier, but not a striking beauty either, just an average girl who’s prettiness you’d notice if you looked past the layers of dirt.

Enjolras

Tall, slender and lightly muscular. Angelically handsome, just as Hugo writes, in the vein of a Greco-Roman statue. Luxuriant blond hair; I most often picture it long, wavy and in a ponytail (since I saw that look onstage first), but I can easily picture it short and curly too, especially with Hugo’s Antinous comparison. Bright blue eyes. Pale skin with rosy overtones “like a young girl’s,” as per Hugo, yet with clear masculine strength in his build. A slender, eternally youthful yet dignified face, with a straight nose, strong chin and quietly stern, ever-determined expression. Again, see the statues of Antinous as a reference.

Gavroche

Average height for an 11- or 12-year-old, but scrawny. Tanned and maybe freckled, like his sister. Light to medium brown hair; I instinctively picture it short and straight like most boy actors’ hair onstage, but I know Hugo saw it as a thick, crazy tangle of curls, so I can imagine that too. No fixed idea of eye color: probably the same as his father’s. A thin face, plain yet bright and expressive, with a wide and loud mouth like his father’s and sister’s. I admit, I imagine him better looking than the wild, ugly little thing Hugo envisioned, but that’s probably true for most of us.

Grantaire

See above: I know my vision of Grantaire isn’t nearly as ugly as Hugo’s, and I don’t imagine him with the huge mustache Hugo sketched him with, but at least I’m not alone in that. I picture him medium height to tall and on the slender side, though I can possibly see him as heavier too. Long or at least longish hair, medium to dark brown, straight yet messy. Brown or hazel eyes. A nondescript face, either round or squarish: I don’t exactly have a clear vision of it, because I know he should be ugly, but I’ve never seen an ugly actor in the role. Based on stage tradition, I tend to picture him with a permanent 5 ‘o clock shadow.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hyperallergic: How a 19th-Century Painter Turned from Reality to Fantasy

Henri Fantin-Latour, “La Lecture” (1877), oil on canvas, 97,2 x 130,3 cm (Lyon, Musée des Beaux-Arts © musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon, photo by Alain Basset)

PARIS — Henri Fantin-Latour’s 19th-century Realist paintings in À fleur de peau at the Musée du Luxembourg remind us that the real must be processed through the flesh and the blood of our eyes. In his early, clear-eyed (yet lovely) paintings that celebrate the luxury of the senses, it is certainly the case that Fantin-Latour’s subject was the reality of the observable world itself. So, in wake of the post-factual politics that brought so much ugliness to the fore with the foul and despicable Donald Trump, it was something of a tonic to peruse Fantin-Latour’s early, unambiguous paintings of substantial, precise, and graspable realities. The mysterious attraction I found in this enlightening retrospective, which includes over 120 paintings, lithographs, drawings, photographs, and preparatory studies, involved taking seriously what one can easily enjoy.

Fantin-Latour’s still life and group portraits accept the powers of observation while rejecting Romantic, exaggerated emotionalism. In the Realist tradition of Gustave Courbet that Fantin-Latour followed, what is intellectually valued is a certain jubilant, but humble, vision typical of science. But as evident in his relatively early painting of flowers and fruit, like “Still Life: Engagement” (1869), Fantin-Latour replaces mere science-based, objective realism with something more seductive. This is especially evident in the sumptuous depiction of the wineglass.

Henri Fantin-Latour, “Roses” (1889), oil on canvas, 44 x 56 cm (collection of Musée des Beaux-Arts Lyon, © musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon, photo by Alain Basset)

Fantin-Latour painted a great number of such flower paintings over his career, as we see with the much later, but stylistically consistent, “Roses” (1889), a painting that demonstrates his talent for the balanced composition of bouquets as well as an exceptional virtuosity in capturing glass textures. These paintings of objective phenomena are like boring relatives we never visit and rarely think about but never doubt the existence of, even though in reality they might have completely changed. Perhaps that is why Fantin-Latour’s conservative-in-style still life paintings sold well and brought him some fame. Indeed, Marcel Proust mentions Fantin-Latour’s work in his masterpiece In Search of Lost Time.

Fantin-Latour’s choice of subject matter — what he makes “real” — does not really matter that much. Painting from photographs, he made some great group portraitures too, such as “Homage to Delacroix” (1864). This large, dark painting is based on a photograph taken 10 years earlier of writers and artists clustered around a portrait of Eugène Delacroix. A year after Delacroix’s death, Fantin-Latour painted it to pay the artist greater homage than he had received in his lifetime. Included in the painting are Fantin-Latour himself (in white shirt, holding a palette), and the painters James Whistler and Edouard Manet. Also featured is the author of Les Fleurs du mal, poet and art critic Charles Baudelaire, who is seated in the lower right-hand corner. This painting, like “A Studio in Les Batignolles” (1870) or “The Reading” (1877), makes use of the realistic but dusty grays of Jean-François Millet, as in his “ The Gleaners” (1857).

Henri Fantin-Latour, “Hommage à Delacroix” (1864), oil on canvas, 160 × 250 cm (Collection of Musée d’Orsay through a 1906 gift by Etienne Moreau-Nélaton, image via Wikimedia Commons)

In his unjustly forgotten early self-portraits, such as “Self-portrait with Slightly Lowered Head” (1861), Fantin-Latour’s self-image becomes another fact of the observable world. Whether stiffly posed or more intimate, such as here, these self-portrait paintings demonstrate his sure hand and acute observational skills that he developed at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, where he devoted much time to copying the works of the Old Masters in the Musée du Louvre.

We gain a glimpse into Fantin-Latour’s creative process in the painting “The Birthday” (1876), which is accompanied by lithographs and drawings that were reworked several times over during 1875, the year the artist married Victoria Dubourg, a fellow painter with whom he collaborated on occasion. The retrospective also provides a rare opportunity to study the artist’s collection of cheesy photographs of naked women that he used to draw from in preparation for his paintings.

Installation view of Henri Fantin-Latour: A fleur de peau at Musée du Luxembourg (image © Rmn-Grand Palais, photo by Didier Plowy)

Toward the end of his career, it becomes clear that faithful reproductions of reality no longer satisfied the artist. Fantin-Latour undercuts the theory of his earlier work with an unexpected series of fuzzy paintings of fairies — something from outside the observable world. Placed next to or against his earlier embrace of bourgeois vision, this late work dealing with fantasy and seduction is incongruous. Here, desire becomes every bit as objective as cut flowers or bearded men in a room.

With this turn, Fantin-Latour veers towards Symbolism, a movement that was a strange amalgam of the social turmoil of its times, its authors swerving between an aesthetics based on effortless asceticism (such as with Odilon Redon and Gustave Moreau) and the decadent debauches associated with Joris-Karl Huysmans, Félicien Rops, and Oscar Wilde. The Symbolists’ political associations were equally split between Catholic right-wing nationalism and anarchist individualism. But either way, Symbolism suggested that reality is a construct, and as such is somewhat fragile. Things neither exist nor fail to exist — they are simply important or unimportant.

Henri Fantin-Latour, “Un atelier aux Batignolles” (1870), oil on canvas (collection of Musée d’Orsay, image via Wikimedia Commons)

This we see in the anti-realist fairy picture “The Night” (1897) and other gauzy works. Nourished by his passion for music and inspired by mythological subjects or odes to the beauty of the female body in the guise of chaste allegories, this work reveals the artist’s lesser-known forays into English Romanticism. Just consider the work of Henry Singleton, Henry Howard, Frank Howard, and Joshua Cristall — all of whom worked at some point in the tradition of small-scale paintings depicting dainty fairy affairs. These artists led the way to the recognized school of Victorian fairy painting, one which had as its admirers luminaries such as Lewis Carroll, William Makepeace Thackeray, Charles Dickens, and John Ruskin, who gave a lecture called Fairy Land in the early 1880s. Under Queen Victoria, fairy paintings appeared systematically in Royal Academy exhibitions (replete at times with their soft, dreamy, erotic imagery) throughout the 19th century.

Henri Fantin-Latour, “La Nuit” (1897) oil on canvas, 61 x 75 cm (image courtesy Musée d’Orsay © Rmn-Grand Palais (musée d’Orsay), photo by Hervé Lewandowsk)

In these later works, Fantin-Latour affirms the palpable reality of seductive phenomena and reconsiders what constitutes the “real.” His earlier, austere Realist art arranged facts and transmitted them to the picture plane; these hyper-lucid paintings seem to affirm “objective reality” as the functional ideal of painting. Perhaps that is why he first tried to oppose Impressionism’s immediacy, the instantaneity of things and their changing appearance in light. In Impressionism one observes phenomena (ironically) too real to be captured in the perfect and complete pictures that are deemed realistic. But, later in life, Fantin-Latour seems to have realized he had ignored the deeper reality of the seduction of the imaginary and its alternative factual intensity.

Henri Fantin-Latour: À fleur de peau continues at the Musée du Luxembourg (19 Rue de Vaugirard, 75006 Paris) through February 12. The show will travel to the Musée de Grenoble (5 Place de Lavalette, 38000 Grenoble, France) March 18–June 18.

The post How a 19th-Century Painter Turned from Reality to Fantasy appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2kbgIxT

via IFTTT

0 notes