#it sucks that hes the closest any gamin can have to a parental figure when hes just a kid himself

Text

Brick Club 4.6.1, 4.6.2

Mme. Thenardier “had disembarrassed herself” of her two youngest boys, which is a fancy way of saying ‘got rid of.’ “Her hatred of the human race began with her boys.” I’d say it’s more like she hates her husband which becomes a hatred of anything that reminds her of him. Her daughters are distanced by merit of gender, but her sons are not so lucky. It’s twisted, but I can understand the psychology that led her to this. Now I’m spinning an entire alternate story where Cosette was born a boy and what that might look like. I have no doubt Fantine wouldn’t act differently either way, but so much of Cosette’s story relies heavily on her characterization as a sweet, innocent young girl.

Magnon pops back up again, she’s an underrated recurring character. She loses her two boys, which is a shame because “these children were precious to their mother; they represented eighty francs a month…the children dead, the income was buried.” Luckily, it really is a buyers market on children in early 19th century France, and the Thenardiers are like 3/4ths of that market.

“At a certain depth of misery, men are possessed by a sort of spectral indifference.” Pssst, it’s alienation. You already know it. Gotta rep my brand.

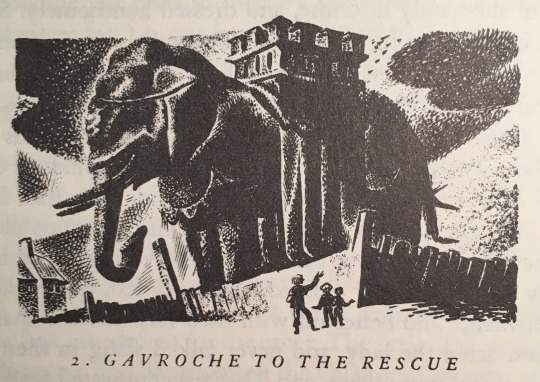

Another utterly gorgeous illustration paired with a mind-bogglingly bad chapter title translation. I’ve got “In Which Little Gavroche Takes Advantage of Napoleon the Great.” Please, Wraxall, why are you doing this?

People are, wow, consistently really awful to children in clear and desperate need in this book. It falls to Gavroche to be the only helpful adult adjacent figure in all of Paris, “and the two children followed him as they would have followed an archbishop.” Some highlights from the Gavroche variety show:

“The bureau is closed, I receive no more complaints.”

“It rains again! Good God, if this continues, I withdraw my subscription.”

“Ah! we have lost our authors. We don’t know now what we have done with them.”

I really like the translation conundrum of Gavroche’s text-language speech. Wilbour translates “Keksekça?” as “Whossachuav?” whereas Hapgood and Wraxall don’t bother to translate it at all. Leaving the original text is probably the right call but I enjoy the linguistic gymnastics of trying to translate and also explain the joke. Weirdly, Hapgood translates all the argot to English while Wilbour leaves it in French.

“All three placed end to end would hardly have made a fathom.” God, that’s kind of the most adorable thing ever. Please someone draw the three Thenardier boys stacked on top of each other wearing a trench coat and still being comically shorter than Montparnasse.

Gavorche and Montparnasse conduct quite the amiable conversation. Their dynamic is pretty interesting, and not what I would expect just from knowing their characters. Montparnasse seems to take Gavroche quite seriously and might even be impressed at some of his remarks. We know Gavroche isn’t so endeared with Montparnasse as to not rob him, and that he’s comfortable enough with the murderer to insult his vanity.

Ok, I want to talk about the elephant, which is a goldmine of symbolism, both for Hugo writing and for us reading. On the first level, the elephant is emblematic of the crumbling of Napoleon’s empire, left to be forgotten and eroded away over time, rats swarming all through the inner workings. “It partook, to some extent of a filth soon to be swept away, and, to some extent, of a majesty soon to be decapitated.” It also represents the transition from empire to, if not a republic, something more domestic, “leaving a peaceable reign to the kind of gigantic stove, adorned with its stove-pipe, which has taken the place of the forbidding nine-towered fortress.” This replacement, and the replacing of feudalist lords with the bourgeoisie is framed as the violent and barbarous past softening into a more civilized society. Although, there is still discontent running fiercely below the domestic facade, “an epoch of which a tea-kettle contains the power.” There is underestimated power in what seems unremarkable. Gavroche uses the elephant to save these two lost boys, when no one else would even let them in their shop.

This takes us neatly into the next layer of symbolism, the disparate utility of the elephant. The elephant is isolated, an eyesore, disdained by the bourgeoisie for being useless. But by falling to this ruin, this “colossal beggar…had taken pity itself on this other beggar, the poor pigmy.” The elephant finds itself on the level of the poor and, in turn, provides for them, just as Gavroche, despite having nothing, provides for those he comes across. Napoleon sought to immortalize his greatness, “he desired to incarnate the people. God had done a grander thing with it, he lodged a child.” This calls all the way back to literally 1.1.1 when Bienvenu tells Napoleon, “You behold a good man, and I a great man.” The bourgeoisie have no use for goodness, they can no longer comprehend the utility of the most basic needs, they only think about usefulness in terms of abstract ideas of greatness. For the gamin who doesn’t have a home or food, the world looks very different; Gavroche doesn’t care about the symbolic might of Napoleon, he cares that the elephant has a roof.

Having said this, I want to take care not to deify the idea of the elephant. It’s easy to get caught up in Hugo’s words here, “This idea of Napoleon…had been taken up by God,” but this is like those “heartwarming” news stories in which a kid sells lemonade to pay for their parent’s medical procedures. Our ire shouldn’t be that the bourgeoisie are so ignorant as to find the elephant useless, it should be that the gamins are in such a desperate situation that they look at a rotting frame of plaster and wood and think “home.”

Related, this is probably why Gavroche is so tough on these kids, while also being incredibly generous. He knows it’s best to get them to adjust quickly to this life, but that doesn’t mean throwing them to the wolves. It’s really painful to watch him have to do this.

#brickclub#les mis#les miserables#4.6.1#4.6.2#gavroche is the absolute best hashtag relatable hashtag mood#it sucks that hes the closest any gamin can have to a parental figure when hes just a kid himself#esp after watching the idyllic relationship between valjean and cosette#anyways gotta love that elephant#that plaster embodiment of just how bullshit the politics of the past 50 years have been

5 notes

·

View notes