#i almost miss 2010s feminism. not entirely but almost

Text

saw someone refer to not knowing how to keep track of your money as "girl math" ......why are we in this weird era of treating women like idiots but repackaging it to sound cute and quirky. We All Need To Stop

75K notes

·

View notes

Text

Short Review on Ducktales 2017

With it’s cancellation announced, I take a look back on the reboot and share my final thoughts on it.

Now, a while back I did say that I didn’t care too much for the show, that I couldn’t get into it, but that was when the first or maybe even second season came around and I wondered if my thoughts changed over time after watching some episodes.

What are my thoughts on it? About the same...-ish. I dunno if I stated this before but I always felt that the 2017 reboot was trying to be too edgy and what I mean by that is that it tries to do more of the Darkwing aspect and often seems to put too much action when Ducktales was more about adventure than action. I mean, sure in some episodes they do stop a bad guy or they save the world in the old show, but they kept this more humble and light hearted feel to it and overall, kept it more of an adventure than just action. All the characters are always pumped up for action and adventure and craziness and not enough seem to be in between that. I especially didn’t like what they did with Webby because she felt like a Gosalyn 2.0. I don’t mind strong female and flawed leads but I felt like 2017 DT was always afraid to show a full on nurturing character, especially a female character.

Don’t worry, we’ll get to her in a minute!

Take Flora from Winx Club.

Her nature is kind, loving and nurturing. She’s completely feminine and vulnerable too. However, she can be pushed to her limits especially when she realizes she’s been taken advantage of and she’s useful in terms of magic and her nurturing side is seen as a strength since she can heal others and take care of things when it’s time for relaxation.

In DT 2017, all the female characters are strong and do have a nurturing side too but there aren’t too much of variety. They’re usually tomboys and as a tomboy myself and gender fluid, there’s nothing wrong with that but I like variety. I don’t think all female leads have to wield a sword or desire action all the time. Sometimes the greatest strength can come from say a seemingly “weak” character because their kindness and even loving nature is their strength and as long as they seem to be useful in some regard and have a brain, I don’t think it’s bad. I think what people assume feminism is that you can’t have even one or two female characters that aren’t bad ass action packed girls and that’s not really what it is. Basically there’s hardly any balance of female characters or even characters in general. They’re all about the same always crazy and pumped up characters or they’re too serious.

Louie is kinda not so much that but he also comes across as whiny especially since his actor is clearly a man doing a kid voice and more often than that I don’t mind it, but their voices for all triplets sorta grated on my nerves and even though I appreciate making the triplets different and having different voice actors, they still kinda sound the same and when they whine it actually hurts my ears. If you don’t have child actors, maybe settle for a woman doing a kid voice. Least even when it’s sorta noticeable it’s not as annoying and yeah I get it. The voices of the old triplets were annoying too but least they sounded their age. I always felt like their voices in the reboot sounded like a man getting strangled whenever they shouted.

Than you have Gyro in the 2017 reboot. They took what used to be this humble, shy friendly male character and turned him into a hipster jerk! I mean come on! Look at his get up! The moment someone sees him they’re gonna know the show was done in the late 2010s. He’s not settle in that appearance and his attitude. He’s so full of himself too! I absolutely HATED that! He’s not even like how Darkwing was full of himself, where he was full of himself but because it was sorta childish full of himself, he came out as charismatic! 2017 Gyro is just...Stuck up, jerk full of himself. I mean, yes he has his kinder moments sometimes but if you’re gonna do strong, action packed female leads, why not make some of the male leads have a humble, shy side? You could go Flora with him and made him sweet and nurturing but still very brilliant. That’s what Gyro was! And I know they wanted to change him up but they didn’t change Scrooge all that much, so I don’t see why they couldn’t have kept Gyro the way he was!

What made the old DT good and even timeless was the fact most of the characters were more humble, the show had a humble feel and I get that the new series characters can be too but the thing is they CAN be, but not most of the time. It’s not their complete nature and yeah that makes them seem rounded in some ways but it also can take away what made the old show welcoming.

And again, I feel like the show is trying to be a bit too action packed and not enough of the adventure or mystery. It seems like the characters are always on edge and ready for anything and again maybe trying to be too much like what Darkwing was instead of more of it’s own thing. Though, again, this is just my opinion and maybe I’m just trying to explain more of the feeling of why I can’t get into it as much as others do and I’m not a nostalgia purest either! I really do try to be open minded with new things! I do even like some of the Disney remakes even if they’re not perfect or no way close to the original. Shoot, another reason that could be is while I did like the original DT, I wouldn’t say I was a die hard fan of it either. In some ways, I think even the original DT can be overrated and wish other shows of the old days got more attention.

Color pallet and art style is okay. I kinda miss the more colorful pallets they used but by no means is awful. It goes make the colors they want to pop out do pop out so it does it’s job. I just think it could have a bit more brighter colors.

Now does that mean I hate DT 2017? No! Far from it! As much as I complain about certain aspects of the show, there’s a lot to enjoy too and even the aspects I don’t like about the reboot, I can understand and get why others may like it. I can admit when something just simply doesn’t do it for me but by no means makes it awful. I do really like Della Duck, despite being another crazy tomboy! She kinda reminds me of me in some ways except for the fact I’m not adventurous in that way and I hate traveling due to anxiety.

I think why I like her the most instead of the other female leads is just she feels more genuine to me. I feel like with characters like say Webby or some of the other female leads, they were like “See! We got a crazy tomboy gal! We’re going against the gender norm!” and focus too much of that and not enough of just making a female strong lead for just simply making a good character.

With Webby, I felt like they were trying too hard to go against the gender norm. Like “Look, she’s totally not the old Webby so you gotta like her! She’s smart, she’s over the top and total geek!” Which, with her I found kinda cheesy and almost fake. I know that’s kinda harsh to say and I kinda feel bad saying it, cuz I know people like this version and I don’t hate the character, I just couldn’t get into her character and again, it felt like they made her the way she did because of the SJW appeal and not out of honesty.

(Note: I’m not entirely against SJW since I do agree with some stuff, but I’m not completely for them either. Put it short, I put myself in between AntiSJW and SJW as I always believe in being more balance especially when it comes to certain topics, thus being fair to both point of views.)

While with Della it felt they just honestly wanted to make her a good character and really funny too! I also like the fact she’s an adult and admits to her mistakes and tries to do better. That’s how you make a strong, GOOD female lead.

(Disney, take freakin note when doing your live action remake female leads! Lookin at you Mulan 2019!)

And lastly, the stuff with Darkwing Duck, YES! I loved it! Anytime they do something that had to do with Darkwing Duck I was down for! I felt like I did when I was watching Darkwing Duck back in the old days! Took me back to my childhood days! I even started to like the new Gosalyn! Like I was with everyone else and wasn’t sure if I liked it but she really grew on me! I really do like her and I’m all for the new remake of the show if it starred these characters!

And I think that’s why I felt this sort of action pack and kind of edginess with the characters fit more with Darkwing Duck than it does with Ducktales. When they did Darkwing Duck it’s fine because Darkwing was about that. With Ducktales, it’s okay but it also feels a bit out of place for me anyway, cuz I always associated the old show with adventure with more humble characters.

So how would I even rate Ducktales. I would probably rate it around a 6 or 7 out of 10 stars, if I had to rate the show at all. It’s not bad and the stuff I don’t like really has to do with more of a personal opinion, rather than something I find wrong with the show. I do recommend seeing it at least a few episodes before drawing a personal opinion and if you have kids that like action and adventure, I know for sure they will get into it.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Taylor Swift Bent the Music Industry to Her Will

By: Lindsay Zoladz for Vulture

Date: December 30th 2019

In the 2010s, she became its savviest power player.

n late November 2019, Taylor Swift gave a career-spanning performance at the American Music Awards before accepting the statue for Artist of the Decade. (Swift was perhaps the perfect cross between the award’s two previous recipients, Britney Spears and Garth Brooks.) Clad in a cascading rose-colored cape and holding court among the younger female artists in attendance - 17-year-old Billie Eilish, 22-year-old Camila Cabello, 25-year-old Halsey - Swift had the queenly air of an elder stateswoman. After picking up five additional awards, including Artist of the Year, she became the show’s most decorated artist in history. “This is such a great year in music. The new artists are insane,” she declared in her acceptance speech, with big-sister gravitas. That night, she finally outgrew that “Who, me?” face of perpetual awards-show surprise; she accepted the honors she won like an artist who believed she had worked hard enough to deserve them.

Swift cut an imposing adult figure up there, because somewhere along the line she’d become one. The 2010s have coincided almost exactly with Swift’s 20s, with the subtle image changes and maturations across her last five album cycles coming to look like an Animorphs cover of a savvy and talented young woman gradually growing into her power. And so to reflect on the Decade in Taylor Swift is to assess not just her sonic evolutions but her many industry chess moves: She took Spotify to task in a Wall Street Journal op-ed and got Apple to reverse its policy of not paying artists royalties during a three-month free trial of its music-streaming service. She sued a former radio DJ for allegedly groping her during a photo op and demanded just a symbolic victory of $1, as if to say the money wasn’t the point. Critics wondered whether she was leaning too heavily on her co-writers, so she wrote her entire 2010 album, Speak Now, herself, without any collaborators. In 2018, she severed ties with her longtime label, Big Machine Records, and negotiated a new contract with Universal Music Group that gave her ownership of her masters and assurance that she (and any other artist on the label) would be paid out if UMG ever sold its Spotify shares. Yes, she stoked the flames of her celebrity feuds with Kanye West, Kim Kardashian West, and Katy Perry plenty over the past ten years, but she’s also focused some of her combative energy on tackling systemic problems and fashioning herself into something like the music industry’s most high-profile vigilante. Few artists have made royalty payments and the minutiae of entertainment-law front-page news as often as Swift has.

Within the industry, Swift has always had the reputation of being something of a songwriting savant (in 2007, when “Our Song” was released, then-17-year-old Swift became the youngest person ever to write and perform a No. 1 song on the Billboard Country chart), but she has long desired to be considered an industry power player, too. A 2011 New Yorker profile of Swift circa her blockbuster Speak Now World Tour noted that she initially intended to follow her parents’ footsteps and pursue a career in business, quoting her saying, “I didn’t know what a stockbroker was when I was 8, but I would just tell everybody that’s what I was going to be.” In an even earlier interview, she fondly recalled the times in elementary school when she stayed up late with her mother, practicing for school presentations. “I’m sick of women not being able to say that they have strategic business minds - because male artists are allowed to,” she said this year in an unusually candid Rolling Stone interview. “And I’m so sick and tired of having to pretend like I don’t mastermind my own business.” Of course, she still spent plenty of time sitting at her piano or strumming her guitar, but in that conversation she painted herself as someone who is also “sit[ting] in a conference room several times a week,” coming up with ideas about how best to market her music and her career.

And so over the past decade, Swift’s face has appeared not just on magazine covers and television screens, but on UPS trucks and Amazon packages. Her songs have been featured in Target commercials and NFL spots, to name just two of her many lucrative partnerships. That New Yorker profile also found her to be uncommonly enthused about the fact that her CDs were being sold in Starbucks: “I was so stoked about it, because it’s been one of my goals - I always go into Starbucks, and I wished that they would sell my album.”

“Taylor Swift is something like the Sheryl Sandberg of pop music,” Hazel Cills wrote recently in Jezebel. “She has propelled her career from tiny country artist into pop machine over the past few years with little shame when it comes to corporate collaborators.” Such brazen femme-capitalism will always be a turnoff to some people (“the Sheryl Sandberg of pop music” is even less of a compliment in 2019 than it was when Lean In was first published), but it’s undeniable that it has helped Swift maintain and leverage her status as a commercial juggernaut more consistently than any other pop star over the past ten years.

In the 2010s, with the clockwork certainty of a midterm election, there was a Taylor Swift album every other autumn. (Yes, there was a three-year gap between 1989 and Reputation, but she all but made up for it with the quick timing of August’s Lover.) The kinds of pop superstars considered her peers did not stick to such rigid schedules: Adele released two studio albums this decade, Beyoncé released three, and even Rihanna - who for the first three years of the decade was averaging an album a year - eventually slowed her roll and will have released just four when the 2010s are all said and done. The only A-plus-list musician who saturated the market as steadily as Swift did this decade was Drake.

Still, Drake’s commercial dominance was more of a newfangled phenomenon, capitalizing on the industry’s sudden reliance on streaming and his massive popularity on platforms like Spotify and Apple Music. Drake might be the artist who rode the streaming wave most successfully this decade, but - with her strategic withholding of her albums from certain platforms until they better compensated artists - Swift was often the one bending it to her will. And she could do that because she didn’t need to rely on it solely: Somehow, against all odds, Taylor Swift still sold records. Like, gazillions of them. When Swift’s 2017 record, Reputation (some critics thought it was a critical misstep, but it certainly wasn’t a commercial one), moved 1.216 million units in its first seven days, Swift became the only artist in history to achieve four different million-selling weeks. And, of course, all four of these weeks came during a decade when traditional album sales were on a precipitous decline. At least for those mere mortals who were not an all-powerful being named Taylor Alison Swift.

“Female empowerment” has been such an ambient, unquestioned virtue of the pop culture of this decade that we have too often failed to take a step back and ask ourselves what sort of power is being advocated for, and if its attainment should always be a cause for celebration. Is “female empowerment” any different from the hollow, materialistic promises of the late ’90s “girl power”? Is “female power” inherently different or more benevolent than its default male counterpart? Maybe this feels like such a distinctly American hang-up because we have not yet experienced that mythic, oft-imagined figure of the First Female President, and have thus not had to contend with the cold reality that, whoever she is, she will, like all of us, be inevitably flawed, imperfect, and at least occasionally disappointing.

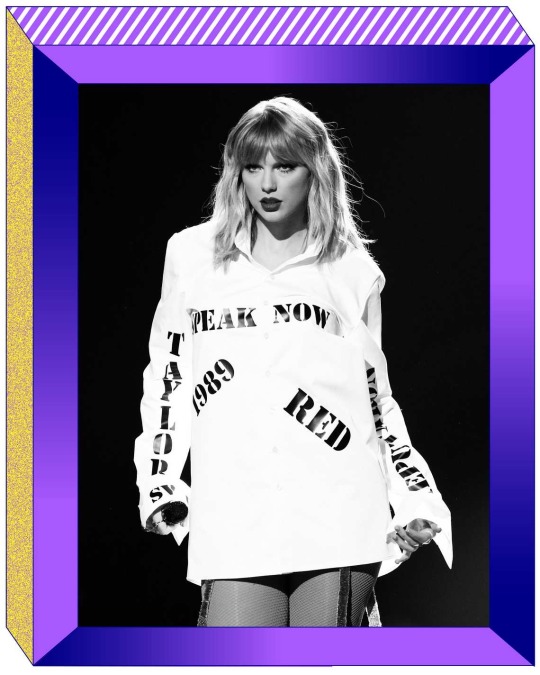

As she’s grown into her own brand of 21st-century American pop feminism - sometimes elegantly, sometimes gawkily - Swift seems to have come to a firm conviction that female power is essentially more virtuous than the male variety. This was a side of herself she celebrated in her AMA performance. Swift opened her medley with a few fiery bars of “The Man,” her own personalized daydream of what gender equality would look like: “I’m so sick of running as fast as I can,” she sings, “wondering if I’d get there quicker if I was a man.” She wore an oversize white button-down onto which the titles of her old albums were stamped in a correctional-facility font: SPEAK NOW, RED, 1989, REPUTATION. Plenty of the millions of people who scrutinize Swift’s every move interpreted her choice of outfit and song as not-so-subtle jabs at Big Machine’s Scott Borchetta and the manager-to-the-stars Scooter Braun, with whom Swift is still in a messy, uncommonly public battle over the fate of her master recordings. (The only album title missing from her outfit was “LOVER,” which happens to be the only one of which she has full ownership.) She has framed the terms of her battle with Borchetta and Braun in strikingly gendered language: “These are two very rich, very powerful men, using $300 million of other people’s money to purchase, like, the most feminine body of work,” she told Rolling Stone. “And then they’re standing in a wood-panel bar doing a tacky photo shoot, raising a glass of Scotch to themselves.” Though she is herself a very rich, very powerful woman, she reads their message to be unquestionably condescending: Be a good little girl and shut up.

It is true that many record contracts are designed to take advantage of young artists, and that young women and people of color are probably perceived by music executives to be the marks most vulnerable to exploitation. But it is also true that Swift signed a legally binding contract, the kind that a businesswoman like herself would have to respect if it were signed by somebody else. Braun, who has been asking to have these negotiations in private rather than on Twitter, claims to have received death threats from her fans.

Even as she’s grown into one of the most dominant pop-culture figures in the world, Swift sometimes still seems to be clinging to her old underdog identity, to the extent that she can fail to grasp the magnitude of her own power or account for the blind spots of her privilege. “Someday I’ll be big enough so you can’t hit me,” she sang on Speak Now’s Grammy-winning 2010 single “Mean,” seemingly oblivious to the fact that, compared to 99.99 percent of the population, she already was. The mid-decade backlash to Swift’s thin-white-celebrity-and-model-studded “girl squad” - none of which was more incisive than Lara Marie Schoenhals’s hilarious parody video - took her by surprise. “I never would have imagined that people would have thought, This is a clique that wouldn’t have accepted me if I wanted to be in it... I thought it was going to be we can still stick together, just like men are allowed to.”

“Female power” is not automatically faultless, and can of course be tainted by all other sorts of biases and assumptions about class, race, and sexual orientation, to name just a few more common pitfalls. Swift’s face-palm-inducing 2015 misunderstanding with Nicki Minaj revealed this, of course, and plenty of people felt that her sudden embrace of the LGBTQ community in the “You Need to Calm Down” was a clumsy overcorrection for her past silence. Maybe she would have gotten where she was quicker if she were a man. But it would take a more complicated, and perhaps less catchy, song to acknowledge she might not have gotten there at all had she not also enjoyed other privileges.

Art has its own kind of power - sneakier and harder to measure than the economic kind. The reason Taylor Swift has been worth talking about incessantly for an entire decade is that she continues to wield this kind, too. “I don’t think her commercial responsibilities detract from her genuine passion for her craft,” a then-17-year-old Tavi Gevinson wrote in a memorable 2013 essay for The Believer. “Have you ever watched her in interviews when she gets asked about her actual songwriting? She becomes that kid who’s really into the science fair.”

After so much industry drama, much of the lived-in, self-reflective Lover is a simple reminder that Swift was and still is a singular songwriter. Yes, this was the decade of such loud, flashy missteps as “Look What You Made Me Do,” “Welcome to New York,” and “Me!,” but it was also a decade of so many quieter triumphs: the pulsing synesthesia of “Red,” the nervous heart flutter of “Delicate,” the sleek sophistication of “Style,” the concise lyricism of “Mean,” the cathartic fun of “22,” the slow-dance swoon of “Lover.” But like so many of her fans, and even Swift herself, I still find the most enduringly powerful song she’s ever written to be “All Too Well,” the smoldering breakup scrapbook released on her great 2012 album Red. “Wind in my hair, I was there, I remember it all too well,” she sings, an innocent enough lyric that, by the end of the song, comes to glint like a switchblade. In a decade of DGAF, ghosting, and performative chill, remembering it all too well might be Swift’s stealthiest superpower. She felt it deeply, can still access that feeling whenever she needs to, and that means she can size you up in a line as concisely cutting as “so casually cruel in the name of being honest.” Forget Jake Gyllenhaal or John Mayer. That’s the sort of observation that would bring Goliath to his knees.

“It is still the case that when listeners hear a female voice, they do not hear a voice that connotes authority,” the historian Mary Beard writes in her manifesto Women & Power, “or rather they have not learned how to hear authority in it.” At least in the realm of pop music, Swift has spent the better part of her decade chipping away at that double standard, and teaching people how to think about cultural power a little bit differently. She sprinkled artful emblems of teen-girl-speak through her smash hits (“Uhhh he calls me and he’s like, ‘I still love you,’ and I’m like, ‘This is exhausting, we are never getting back together, like, ever”) and did not abandon her effusive love of kittens and butterflies in order to be taken seriously. As an artist and a businesswoman, she made the power of teen girls - and the women who used to be them - that much more perilous to ignore. Because they’ve been there all along, and they remember all too well.

#taylor swift#vulture#article#about taylor#2010s#TAS business#music industry#songwriting#all the eras

181 notes

·

View notes

Text

Taylor Swift Bent the Music Industry to Her Will

In the 2010s, she became its savviest power player.

In late November 2019, Taylor Swift gave a career-spanning performance at the American Music Awards before accepting the statue for Artist of the Decade. (Swift was perhaps the perfect cross between the award’s two previous recipients, Britney Spears and Garth Brooks.) Clad in a cascading rose-colored cape and holding court among the younger female artists in attendance — 17-year-old Billie Eilish, 22-year-old Camila Cabello, 25-year-old Halsey — Swift had the queenly air of an elder stateswoman. After picking up five additional awards, including Artist of the Year, she became the show’s most decorated artist in history. “This is such a great year in music. The new artists are insane,” she declared in her acceptance speech, with big-sister gravitas. That night, she finally outgrew that “Who, me?” face of perpetual awards-show surprise; she accepted the honors she won like an artist who believed she had worked hard enough to deserve them.

Swift cut an imposing adult figure up there, because somewhere along the line she’d become one. The 2010s have coincided almost exactly with Swift’s 20s, with the subtle image changes and maturations across her last five album cycles coming to look like an Animorphs cover of a savvy and talented young woman gradually growing into her power. And so to reflect on the Decade in Taylor Swift is to assess not just her sonic evolutions but her many industry chess moves: She took Spotify to task in a Wall Street Journal op-ed and got Apple to reverse its policy of not paying artists royalties during a three-month free trial of its music-streaming service. She sued a former radio DJ for allegedly groping her during a photo op and demanded just a symbolic victory of $1, as if to say the money wasn’t the point. Critics wondered whether she was leaning too heavily on her co-writers, so she wrote her entire 2010 album, Speak Now, herself, without any collaborators. In 2018, she severed ties with her longtime label, Big Machine Records, and negotiated a new contract with Universal Music Group that gave her ownership of her masters and assurance that she (and any other artist on the label) would be paid out if UMG ever sold its Spotify shares. Yes, she stoked the flames of her celebrity feuds with Kanye West, Kim Kardashian West, and Katy Perry plenty over the past ten years, but she’s also focused some of her combative energy on tackling systemic problems and fashioning herself into something like the music industry’s most high-profile vigilante. Few artists have made royalty payments and the minutiae of entertainment-law front-page news as often as Swift has.

Within the industry, Swift has always had the reputation of being something of a songwriting savant (in 2007, when “Our Song” was released, then-17-year-old Swift became the youngest person ever to write and perform a No. 1 song on the Billboard Country chart), but she has long desired to be considered an industry power player, too. A 2011 New Yorker profile of Swift circa her blockbuster Speak Now World Tour noted that she initially intended to follow her parents’ footsteps and pursue a career in business, quoting her saying, “I didn’t know what a stockbroker was when I was 8, but I would just tell everybody that’s what I was going to be.” In an even earlier interview, she fondly recalled the times in elementary school when she stayed up late with her mother, practicing for school presentations. “I’m sick of women not being able to say that they have strategic business minds — because male artists are allowed to,” she said this year in an unusually candid Rolling Stone interview. “And I’m so sick and tired of having to pretend like I don’t mastermind my own business.” Of course, she still spent plenty of time sitting at her piano or strumming her guitar, but in that conversation she painted herself as someone who is also “sit[ting] in a conference room several times a week,” coming up with ideas about how best to market her music and her career.

And so over the past decade, Swift’s face has appeared not just on magazine covers and television screens, but on UPS trucks and Amazon packages. Her songs have been featured in Target commercials and NFL spots, to name just two of her many lucrative partnerships. That New Yorker profile also found her to be uncommonly enthused about the fact that her CDs were being sold in Starbucks: “I was so stoked about it, because it’s been one of my goals — I always go into Starbucks, and I wished that they would sell my album.”

“Taylor Swift is something like the Sheryl Sandberg of pop music,” Hazel Cills wrote recently in Jezebel. “She has propelled her career from tiny country artist into pop machine over the past few years with little shame when it comes to corporate collaborators.” Such brazen femme-capitalism will always be a turnoff to some people (“the Sheryl Sandberg of pop music” is even less of a compliment in 2019 than it was when Lean In was first published), but it’s undeniable that it has helped Swift maintain and leverage her status as a commercial juggernaut more consistently than any other pop star over the past ten years.

In the 2010s, with the clockwork certainty of a midterm election, there was a Taylor Swift album every other autumn. (Yes, there was a three-year gap between 1989 and Reputation, but she all but made up for it with the quick timing of August’s Lover.) The kinds of pop superstars considered her peers did not stick to such rigid schedules: Adele released two studio albums this decade, Beyoncé released three, and even Rihanna — who for the first three years of the decade was averaging an album a year — eventually slowed her roll and will have released just four when the 2010s are all said and done. The only A-plus-list musician who saturated the market as steadily as Swift did this decade was Drake.

Still, Drake’s commercial dominance was more of a newfangled phenomenon, capitalizing on the industry’s sudden reliance on streaming and his massive popularity on platforms like Spotify and Apple Music. Drake might be the artist who rode the streaming wave most successfully this decade, but — with her strategic withholding of her albums from certain platforms until they better compensated artists — Swift was often the one bending it to her will. And she could do that because she didn’t need to rely on it solely: Somehow, against all odds, Taylor Swift still sold records. Like, gazillions of them. When Swift’s 2017 record, Reputation (some critics thought it was a critical misstep, but it certainly wasn’t a commercial one), moved 1.216 million units in its first seven days, Swift became the only artist in history to achieve four different million-selling weeks. And, of course, all four of these weeks came during a decade when traditional album sales were on a precipitous decline. At least for those mere mortals who were not an all-powerful being named Taylor Alison Swift.

“Female empowerment” has been such an ambient, unquestioned virtue of the pop culture of this decade that we have too often failed to take a step back and ask ourselves what sort of power is being advocated for, and if its attainment should always be a cause for celebration. Is “female empowerment” any different from the hollow, materialistic promises of the late ’90s “girl power”? Is “female power” inherently different or more benevolent than its default male counterpart? Maybe this feels like such a distinctly American hang-up because we have not yet experienced that mythic, oft-imagined figure of the First Female President, and have thus not had to contend with the cold reality that, whoever she is, she will, like all of us, be inevitably flawed, imperfect, and at least occasionally disappointing.

As she’s grown into her own brand of 21st-century American pop feminism — sometimes elegantly, sometimes gawkily — Swift seems to have come to a firm conviction that female power is essentially more virtuous than the male variety. This was a side of herself she celebrated in her AMA performance. Swift opened her medley with a few fiery bars of “The Man,” her own personalized daydream of what gender equality would look like: “I’m so sick of running as fast as I can,” she sings, “wondering if I’d get there quicker if I was a man.” She wore an oversize white button-down onto which the titles of her old albums were stamped in a correctional-facility font: SPEAK NOW, RED, 1989, REPUTATION. Plenty of the millions of people who scrutinize Swift’s every move interpreted her choice of outfit and song as not-so-subtle jabs at Big Machine’s Scott Borchetta and the manager-to-the-stars Scooter Braun, with whom Swift is still in a messy, uncommonly public battle over the fate of her master recordings. (The only album title missing from her outfit was “LOVER,” which happens to be the only one of which she has full ownership.) She has framed the terms of her battle with Borchetta and Braun in strikingly gendered language: “These are two very rich, very powerful men, using $300 million of other people’s money to purchase, like, the most feminine body of work,” she told Rolling Stone. “And then they’re standing in a wood-panel bar doing a tacky photo shoot, raising a glass of Scotch to themselves.” Though she is herself a very rich, very powerful woman, she reads their message to be unquestionably condescending: Be a good little girl and shut up.

It is true that many record contracts are designed to take advantage of young artists, and that young women and people of color are probably perceived by music executives to be the marks most vulnerable to exploitation. But it is also true that Swift signed a legally binding contract, the kind that a businesswoman like herself would have to respect if it were signed by somebody else. Braun, who has been asking to have these negotiations in private rather than on Twitter, claims to have received death threats from her fans.

Even as she’s grown into one of the most dominant pop-culture figures in the world, Swift sometimes still seems to be clinging to her old underdog identity, to the extent that she can fail to grasp the magnitude of her own power or account for the blind spots of her privilege. “Someday I’ll be big enough so you can’t hit me,” she sang on Speak Now’s Grammy-winning 2010 single “Mean,” seemingly oblivious to the fact that, compared to 99.99 percent of the population, she already was. The mid-decade backlash to Swift’s thin-white-celebrity-and-model-studded “girl squad” — none of which was more incisive than Lara Marie Schoenhals’s hilarious parody video — took her by surprise. “I never would have imagined that people would have thought, This is a clique that wouldn’t have accepted me if I wanted to be in it … I thought it was going to be we can still stick together, just like men are allowed to.”

“Female power” is not automatically faultless, and can of course be tainted by all other sorts of biases and assumptions about class, race, and sexual orientation, to name just a few more common pitfalls. Swift’s face-palm-inducing 2015 misunderstanding with Nicki Minaj revealed this, of course, and plenty of people felt that her sudden embrace of the LGBTQ community in the “You Need to Calm Down” was a clumsy overcorrection for her past silence. Maybe she would have gotten where she was quicker if she were a man. But it would take a more complicated, and perhaps less catchy, song to acknowledge she might not have gotten there at all had she not also enjoyed other privileges.

Art has its own kind of power — sneakier and harder to measure than the economic kind. The reason Taylor Swift has been worth talking about incessantly for an entire decade is that she continues to wield this kind, too. “I don’t think her commercial responsibilities detract from her genuine passion for her craft,” a then-17-year-old Tavi Gevinson wrote in a memorable 2013 essay for The Believer. “Have you ever watched her in interviews when she gets asked about her actual songwriting? She becomes that kid who’s really into the science fair.”

After so much industry drama, much of the lived-in, self-reflective Lover is a simple reminder that Swift was and still is a singular songwriter. Yes, this was the decade of such loud, flashy missteps as “Look What You Made Me Do,” “Welcome to New York,” and “Me!,” but it was also a decade of so many quieter triumphs: the pulsing synesthesia of “Red,” the nervous heart flutter of “Delicate,” the sleek sophistication of “Style,” the concise lyricism of “Mean,” the cathartic fun of “22,” the slow-dance swoon of “Lover.” But like so many of her fans, and even Swift herself, I still find the most enduringly powerful song she’s ever written to be “All Too Well,” the smoldering breakup scrapbook released on her great 2012 album Red. “Wind in my hair, I was there, I remember it all too well,” she sings, an innocent enough lyric that, by the end of the song, comes to glint like a switchblade. In a decade of DGAF, ghosting, and performative chill, remembering it all too well might be Swift’s stealthiest superpower. She felt it deeply, can still access that feeling whenever she needs to, and that means she can size you up in a line as concisely cutting as “so casually cruel in the name of being honest.” Forget Jake Gyllenhaal or John Mayer. That’s the sort of observation that would bring Goliath to his knees.

“It is still the case that when listeners hear a female voice, they do not hear a voice that connotes authority,” the historian Mary Beard writes in her manifesto Women & Power, “or rather they have not learned how to hear authority in it.” At least in the realm of pop music, Swift has spent the better part of her decade chipping away at that double standard, and teaching people how to think about cultural power a little bit differently. She sprinkled artful emblems of teen-girl-speak through her smash hits (“Uhhh he calls me and he’s like, ‘I still love you,’ and I’m like, ‘This is exhausting, we are never getting back together, like, ever”) and did not abandon her effusive love of kittens and butterflies in order to be taken seriously. As an artist and a businesswoman, she made the power of teen girls — and the women who used to be them — that much more perilous to ignore. Because they’ve been there all along, and they remember all too well.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Franchises that are SJW or have now turned SJW

My Little Pony: Friendship Is Magic is SJW - I put it on the first stage because it's not SJW material, but Tara Strong herself is an actual SJW.

IDW Transformers is SJW - IDW's series of Transformers is SJW because they pander to SJW aspects like LGBT themes and feminism. (Please don't get me started on the abomination that was Combiner Wars......)

Thomas and Friends is SJW (Now) - Thomas and Friends was formerly just an innocent edutainment show, but then it pandered to SJWs with their shoehorned identity politics and feminism. Hence why it is on the third stage. In 2018, the series rebranded as Thomas & Friends: Big World! Big Adventures!, seeing Thomas travel to other countries in order to meet engines belonging to other racial ethncities for the sake of pandering to audiences with other skin colours, and the main cast is changed to be more feminist-friendly, with series staples Edward and Henry being written out in favour of Nia and Rebecca, two new brightly-coloured female main characters who only exist to please SJWs by serving as token “I don’t need a man” feminists in order to teach female audiences about women and girls getting a severe lack of recognition and that being female now needs to be taken seriously by ensuring that men learn to treat women more equally and with the respect they need. One brief scene of an episode also included a gay couple, hence also ticking the box for pandering to the LGBT community.

The Loud House is SJW - The Loud House is a fucking kid's cartoon, and yet it has SJW aspects of the show considering it panders to the LGBT community (Luna's bisexuality and Clyde McBride having two fathers) and feminism with the main cast being almost entirely made up of female characters except for Lincoln himself (Ten out of eleven of the main characters; all the Loud Sisters are proof). Hell, even Grey DeLisle Griffin, one of the actresses in the show, is an SJW herself!

Steven Universe is SJW - Like how IDW Transformers and The Loud House did so, this show panders to SJW aspects considering the gems are lesbians. What makes me put Steven Universe above both of them is that I am infuriated that all the crystal gems do not have a sex. I'm sorry, but A. You have to have a sex, and B. There are only two sexes, male and female. Stop making up all these fake genders and treating as if being genderless requires special treatment.

Overwatch is SJW - Overwatch panders to SJWs so bad that it not only panders to the LGBT community (characters who identify as gay) and feminism, but also FUCKING COMMUNISM!!!!!! Just why!?!?!? Communism is in fact, worse than shoehorning identity politics (Which the game has), LGBT aspects, and misandrist feminism all in fucking one! Well, you can't have a Blizzard without such special snowflakes..... (Pun intended considering Blizzard made the game) Also, why HAVEN'T I made a They Live meme out of that yet!?

Funimation is SJW - Funimation went from being pros at dubbing to racists who fight racists. Funimation is a very shady place to go; Jamie Marchi and other actors shoehorn SJW lines in dubs of our favorite anime (She for example shoehorned politics in my favorite anime; Miss Kobayashi's Dragon Maid; hence why I watch it in JP all the time). Not to mention Monica Rial is trying to kick Vic Mignogna despite the latter did nothing wrong, and Chris Sabat is a literal predator. Like..... Harvey Weinstein levels.....

Disney is SJW - Well the culprit that truly started it all was Bob Iger and ABC News; weren't they? I never really cared for Disney, but when they went complete SJW, I started to hate them. I hated EVERY subdivision they had (Sans the Infinity Saga of the MCU and Pre-2010's Marvel Comics). I never liked Pixar, Lucasfilm is woke as fuck, and they bought the living crap out of Fox despite they hated Disney (The Simpsons Movie was proof before the acquisition that happened 12 years later from then). They shoehorn LGBT aspects, feminism, identity politics, simple politics, and FUCKING misandry! They're misandrists...... at least towards straight white males...... This is why I am boycotting Star Wars Episode IX: The Rise of Skywalker! I may have seen The Last Jedi (Regretfully), but I'd say it's about time to give karma by boycotting The Rise of Skywalker. They shoehorn all that unnecessary bigotry crap in stuff we once loved like Marvel Comics (And the MCU by an extent), Lucasfilm (Especially Star Wars), and even Fox Entertainment....... (To be fair, they were acting like this prior to the acquisition) Okay, if you're a Pixar fan, you might want to worry.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

#personal

I keep referencing this Chris Morris interview lately, mostly to myself. I try to talk to people in real life but the things other people take seriously aren't as important as any words I try to speak outloud. This is a trend that Morris and crew began to target in the late nineties when Brass Eye was released. When asked if Brass Eye could happen at the time during the Trump administration, he replied staunchly it could not. Back in the late nineties people took themselves far too seriously in the news. So it was easier to lampoon. These days it feels like a regression. Everyone has a statement to unload on you. A complex series of opinions, arguments, and rules about this or that. Some of them have some weight. Others are carried away by counter arguments and burnt at the stake. The only reason a statement, argument, or ideological battle penetrates the news is to simply kick it around for two weeks in a cycle. It never reaches any sort of consensus. It never diffuses into at the very least a case of agreeing to disagree. The Met Gala recently is a fine example of this. Statement fashion is simply meant to nudge the conversation into focus. At it's very minimum the shock is meant to jolt someone out of this seriousness. To rattle them away from their protective shell to change the dialogue. Think tax the rich or peg the patriarchy. Neither of them if you flesh out the argument have much teeth to them. I'm sure you could find yourself at a party defending either argument. "How many stocks do you have in the bank Mister!" Or why victims of childhood sexual harassment and violence might feel a little differently about proving how you might be able to face the patriarchy in a less violent and humiliating way. This is that none of us are defending a 35,000 dollar ticket to the Met Gala in the first place. There were plenty of other statements. After all the ideological dust settled I almost never realized that Iris Van Herpen designed Grimes suit of armor. If I were too clouded by the ideology I would have missed that legitimate moment of genius. I'm a technologist by profession. I have years of 3D fabrication support. I've often found myself drawn into the intersect of technology and fashion. The embroidery machines that print out all the stupid little poetry that gets stolen from other artists? Those are pretty complex to operate. Without them none of this would be possible. And yet good statement fashion does get people talking. But fashion is more than statements. Especially from the rich and wealthy. And if we don't talk about all of it, we start to realize who controls the flow of the dialogue when it goes petty. We're supposed to move on from these arguments like exhibits in a museum. Not get stuck on one or two moments and use them as a soapbox to drown out the entire room. Statement fashion gets people's attention. I wore undercover for years only to find for years people thought I was an undercover cop. I wear a mouse on a shirt and suddenly my porch is overflowed with them. I hold a raccoon in my arms in Korea one trip and the next year my porch is flooded with them as well. You like animals so much! Prove it!

Prove it was also a song by the underground band Television. I was introduced to them by the king of statement fashion itself, Jun Takahashi. I've worn undercover for years at this point. The story of undercover during the Scab years is an interesting insight into what Jun was trying to express at the core. His assistants were getting food in London on a break. An old woman came up to them and offered them a banana. She thought they were homeless. They were excited because the fashion they were wearing felt real and unpretentious. It blended in and confused people in such a way that it was not high brow or high fashion. It was accessible. It was street level. And it was largely coopted by the ultra rich and worn far too seriously for its own good. For people like myself who wore it out of love to provoking real conversation, it did the opposite. It cast me into a shadow realm where people thought what I was saying enabled them to push the limit. To use people like myself as cover in terms of hijacking authenticity. You used to wear undercover as a badge of honor in Japanese street wear. It was designed for rebels after all. You could wear a t-shirt that simply said RAT out in the street and assume if it applied to someone they'd read into it. But nobody including myself really thought you'd be able to change shit with a t-shirt. In America, people wear rebellious shit to express this idea of freedom. With Jun's stuff, it was all centered around this idea of individualism and anarchy. You can be who you are and there are so many variants of human that there is no comparison. America always wants you to prove it. Prove the right to be alone. Prove the right not to mix with the general population to avoid dilution. To avoid being neutralized or have a narrative hijacked. Nowadays you can't even afford to have a statement without someone explaining it for you behind your back. When the streets become the runway, retaliation happens outside the niceties of press and junkets. It happens with real unbridled emotions. The statements you throw into people's faces don't get moderated by it kids, secret tribunals of the ultra rich or your heroes. They get dealt with in a violent and sometimes mob like fashion by people who take themselves so seriously that their arguments against you are louder than a bomb or a nuclear powered submarine. And everything starts to contradict itself so much that none of us have the energy to argue. We just start mocking it. And the entire situation gets worse.

When it comes to a person like myself, I live in a surreal shadow world where the worst Black Mirror plot lines get tested. I've been writing and making statements for years. I've carefully parsed the arguments online. I've defended myself against an invisible hoard to let people know I am not like other people. And yet in America, until they can throw you in a group you are still nobody. You have to be attached to an ecosystem. A financial sink hole that can sell back your ideas to you instead of compensating you for the trouble. I can't take America seriously anymore even when it comes to it's idea of freedom. It lies to maintain a status quo. It constantly lies. It holds it's head high while sniffing the coke back into it's nose and proudly proclaims how it cares. And when people like myself stare it back in the face with our rotting street wear clothes from early 2010, it's a laugh. It believes until it has fully roasted the juices out of you then you are ready to be carved up. And we buy into it consistently. We waste our time feeding into arguments that have no intent on reaching a consensus. It's always you are either for us or against us. Go back and rally with your people. If you can't find your people it must mean you are mentally ill. America can never take the blame. If you catch it off guard it will figure out a way to trash you or cause a diversion. And so making statements to fuel an argument you can't win becomes a lesson in tedium. We should, by all means, continue to make fun of it. But the more we take these arguments seriously, we miss the real problems. We neglect the real art. We see that there's a good 35,000 dollar barrier to being heard. If we're lucky maybe we stitched together the rags these people wear. To me there have been statements in the populist context that have far more penetration into poking a hole in the patriarchy. I'm supposed to preface this by saying I own stock in some company. But I'm not trying to sell a portfolio. And it'd be kind of laughable to say that I'm only serious about feminism by putting my money where my mouth is to break this glass ceiling. The glass ceiling is there for a lot of us if minimum wage can't get us into the Met Gala. These statements are supposed to give you an idea to confront things in your own way. Not some secret way to groom you into humiliation and destroy your sense of self and sexuality. I write statements every week here most of the time. And they get chuckled at by friends and whoever these days spies on me to see how I deal with dead mice on my porch. Aren't I doing enough by saying something for free? I don't get paid to write any of these words. I don't get paid to talk about any of these people. What was that quote about art being counter revolutionary if it isn't accessible by the regular people? What I could do with a four hundred dollar statement t-shirt I can do with a color. Maybe I could make a statement shirt myself and have it ripped off by an incompetent designer one day. I could point at the screen and say "I copyrighted that statement." And look where it is now. Not in my wallet. Not anywhere near the 35,000 dollar ticket price to point back at the camera. Do you see me? No you don't. People in that realm only see themselves. And we take them and their arguments so seriously for what? A laugh hopefully. Because nothing is going to change if we're locked on the outside looking in at a bonfire of vanities. Witches get roasted either way. <3 Tim

0 notes

Text

Why do we still need feminism?

To everyone wondering why those loud, obnoxious feminists are still protesting today: American women have had mostly-equal rights for less than 40 years out of the entire recorded history of the Western world, thanks to loud, obnoxious feminists like the ones marching and protesting in cities across the US as I type this. There is currently a considerable and disturbing push by some conservative/religious groups to revert some of our hard-fought rights and freedoms to what they were back when we were considered property more than people.

To outline some of the injustices American women face, in case you're wondering what's wrong with our current set of rights and freedoms:

1 in 5 women will be sexually assaulted or raped during her lifetime. Of those, fewer than 1/3 are reported to police.

For every 1000 women who are raped by men, 994 of the men who rape them will never see the inside of a jail cell for that crime.

As of 2014, US police departments had 400,000 untested rape kits sitting around, gathering dust.

31 US states allow a rapist to sue for custody of a child conceived during that rape, and most of those states will not allow the mother to give the child up for adoption unless the rapist father is notified and gives consent. There are currently multiple bills in state senates which would also prevent a woman from aborting a child conceived by rape unless the father gives consent.

It is still an extremely common tactic for a rape trial to focus not on the rapist's crime, but on the entire sexual history of the female victim, what she was wearing, who she was with, whether or not she had been drinking, and often trying to coerce her into admitting it was consensual all along and she's just trying to save her reputation by calling it rape.

Rape is the only crime for which arguing that the temptation was too clear and obvious to resist is treated as an admissible and sometimes clearing defense.

1 in 3 women will experience domestic violence. 1 in 4 women will experience *severe* domestic violence.

As of 2014, 38 million US women had experienced domestic partner violence.

Also as of 2014, 4.77 million US women experience domestic partner violence every year.

Between 2001 and 2013, more than twice as many women were murdered by their male romantic partners than there were soldiers killed in our overseas war efforts.

Disabled women are 40% more likely to experience domestic violence than normally-abled women, and it's more likely to be severe violence.

Marital rape has only been illegal in all 50 states since 1993. Many states still have exceptions to the law, limit the degree of assault it can be considered as, and/or do not prosecute it as seriously as other rape and assault.

Most domestic abuse is never prosecuted.

Abused women lose a collective 8 million days of paid work every year directly as a result of their abuse.

The leading cause of death among pregnant women is being murdered by the father of their child.

The US has the highest maternal mortality in the developed world.

The US is one of two countries in the entire world without paid maternity leave, the other being Papua New Guinea.

Right-to-work states routinely overlook the firing and laying-off of pregnant women because employers abuse the loophole of not explicitly stating that as the reason.

Pregnant women are routinely denied even minor accommodations by employers, such as carrying a water bottle or being allowed to use the restroom more than once every four hours.

Access to contraception is still a hotly-debated subject, and a woman's employer can legally dictate her reproductive choices based on THEIR religious beliefs.

The most effective contraception methods are an entire month's wages for a woman earning minimum wage and who has no access to insurance.

Hormonal contraception has significant and sometimes fatal side-effects that were only approved because the testing was done on impoverished minorities, and it was assumed this would be the primary market for hormonal contraception.

Access to abortion is being increasingly restricted in many states, which has seen a corresponding rise in maternal mortality, infant mortality, and suicide by pregnant women.

Women accessing health care reproductive health clinics such as Planned Parenthood frequently face angry and even violent protestors.

Fake "crisis pregnancy centers" are legal in many states. These are not bound by HIPAA laws and often put their duped patients in actual physical danger.

A Texas anti-abortion group with 30,000 members infiltrated pro-choice groups and hatched a scheme to literally kidnap pregnant women by offering them rides to Planned Parenthood and holding them captive until they'd missed their appointment and/or agreed not to abort. None of them got into any legal trouble for suggesting this.

It is legal in some states for the state to keep a brain-dead pregnant woman on life support indefinitely, regardless of her wishes, her family's wishes, and the stage of pregnancy.

Women are more than twice as likely to die of a heart attack than men are, for the sole reason that their symptoms aren't taken seriously.

Obese women, especially minorities, frequently go without adequate care or any care at all in all levels of medical care, from the general practitioner's office to the emergency room.

35% of single mothers live at or below the poverty line, even though most of them have full-time jobs.

68% of the elderly poor are women.

60% of minimum-wage workers are women.

More than 70% of those living at or below the poverty line are women and children.

There is no affordable child care. A single mother working at a full-time minimum wage job is likely to spend half her income on day care. This forces her to either drop out of the workforce entirely and take government benefits, or to take a second job and essentially never see her own child.

The gender wage gap is real. At all levels of employment in all industries, women are frequently paid less than their male coworkers despite having the same experience, the same seniority, and the same education.

Sexism is rampant in many industries, particularly STEM and manual labor. This leads to less participation by women who feel they will receive unfair treatment from employers and coworkers alike.

The number of women earning degrees in computing-based STEM fields has dropped from 37% to 18% since the 1980s. This was largely due to the creation of hierarchies, hiring practices, and social networking in the 1990s that explicitly favoured men.

Female video game developers routinely receive gender-based harassment online, with an entire socio-political movement of angry young men (GamerGate) emerging because a female game developer was given what they perceived to be an unfairly-high rating on her game by a journalist with whom she subsequently entered into a relationship.

Female celebrities routinely deal with dangerous stalkers, with a number of them being assaulted and/or murdered by such, and our cultural reaction is to tell them that's what they get for being famous. Meanwhile, John Lennon's killer has been in prison since 1980 and is one of the most widely reviled men in America.

Women online in any capacity routinely receive gender-based harassment, demeaning comments, and unsolicited photos of male genitalia.

Women on dating sites frequently receive so much harassment that they are forced to delete their profiles.

The cultural reaction to nude/topless photos of any woman being stolen and posted online is that she got what she deserved for taking them in the first place. Revenge porn (selling nudes/sex tapes of your ex to shame them and ruin their lives/careers by sending links to their family and coworkers) is legal in most states, with females comprising almost 100% of victims. Very little legal recourse exists for victims.

Filming yourself having sex with a woman without her knowledge and selling the video to a porn site is not only legal, but is a popular category amongst viewers.

Womens' Studies is the most frequent butt of every joke made about "useless" college degrees.

Career fields that are high-paying, high prestige, and male-dominated lose their prestige and wages as more women enter the field. This is an observable and frequently repeated trend, and it generally only takes 5-10 years from the time when the number of women in the field exceeds 15-20%.

2017 marks the first year EVER that women have exceeded 20% representation in the Senate, and 19% in the House. Only four are minorities, with three newcomers joining Mazie Hirono, who had been only the second minority woman to ever sit on the Senate until the Nov. 2016 election cycle.

The first and only female Native American federal judge was appointed in 2014. The first white female federal judge was appointed in 1933, the first black female federal judge was appointed in 1966, and the first Asian female federal judge was appointed in 2010. Despite these minor gains, 73% of state and federal judges are still male.

-----

This seems like an exhaustive list, doesn't it? Imagine how exhausting it is to be living it and having to explain it nearly 100 years after the Suffragettes were cruelly derided in editorials, comments, and assaulted on the streets over wanting something to be done about many of these very same issues.

161 notes

·

View notes

Video

kickstarter

Interview: ELLY BLUE!

@solarpunks spoke with Elly Blue who is the co-owner of Microcosm Publishing. Where she publishes books about the feminist bicycle revolution among many other topics related to self-empowerment. She's the author of several books including Bikenomics; How Bicycling Can Save the Economy. She lives in Portland, Oregon, USA, which isn't really the bicycle utopia everybody thinks it is.

Details about the Biketopia! Kickstarter can be found at the bottom of this post.

Publishing

SPS! What is it about physical publishing that excites you in 2017?

EB: Oh, I love it. Everything about publishing excites me. It’s a big, complicated puzzle and there is no limit to how much you can learn or what you can accomplish. My favorite part, if I had to pick one, is seeing the way people respond to our books and zines in our store and at events—like they’ve been hungry for a long time and have just spotted some really delicious food. That’s what’s most fulfilling: producing books that speak to people and help them imagine the world and their lives in different ways.

SPS! Your first kickstarter was back in 2010. Since then you have launched at least 23 campaigns to get various zines and books printed - It’s obviously a sustainable model to get things done/published:

Is your goal to build a movement, grow a community, or both?

EB: Both! My official job title nowadays is “marketing director.” For a number of years I was a bicycle activist in Portland, and marketing is nearly identical to activist movement building. For either one, the community has to exist first, or at least enough people who would be part of the community if they knew it existed. Having good literature that represents that movement and its debates and brings it to a wider audience can help a community grow and help members find each other and see the bigger picture.

SPS! If you were starting a zine for the first time in 2017 would you still use Kickstarter or use another platform - Patreon etc? or do something else?

EB: Funny you ask -- I’m actually bringing Taking the Lane zine back this year. I gave it up for books for a while, but honestly, zines sell better. They feel more special, I think. People seek them out and are really stoked to get their hands on them. Publishing books is great, but the stuff I do under my feminist bicycling imprint doesn’t really fit on any shelf at a bookstore, so I’m dialing a lot of it back to the underground. But to answer your question, I’m planning to keep using Kickstarter to fund the zines. And I’m getting ready to open a Patreon later this month! Microcosm, my parent company, just launched one, and I’m learning a lot about how to use it. https://www.patreon.com/microcosm

SPS! Theoretically, do you think there is any utility in small scale niche publishers/zines who rely on their community for support to publish their accounts?

EB: Sure. But it’s the other way around—the community support is what demonstrates the utility and justifies doing this stuff in the first place. I see the zines and books as a service to the community and a way to focus it, amplify it, and grow it, rather than the community being a separate thing or an appendage of the publications. What I choose to publish, and who contributes, and how it’s positioned, all of that happens in response to what the community is doing, and also to looking at the community and thinking about who is and isn’t represented.

Feminism

SPS! Your first ‘Taking the lane’ zine was called ‘Sharing the Road with Boys’ with writing by you on sexist encounters in cycling and what to do about it. Apart from society’s background misogyny/sexism, how did that zine and subsequent series come about?

EB: I spent a year as the managing editor at BikePortland.org and one of the last things I did there was write up a big blog post about the overt sexism I’d encountered while covering the bike industry, particularly on the sports side of the industry but also in advocacy. The response was tremendous, and Jonathan Maus, the blog’s publisher, advised me to keep writing about that. I did keep writing, but I didn’t have anywhere to publish it—so when my partner, Joe Biel, invited me to join him on a book and zine tour, it made sense to flesh it out and turn it into a zine. I didn’t have enough money to print it, but a friend told me about Kickstarter and I was off and running. I had no idea what it would turn into.

The initial focus on sexism was a good way to start off the series. People were indignant and inspired to share their own stories and it was a rallying cry that was easy to put out there. But the reason I stuck with it is because when people started sending me their own submissions, mostly personal essays, they were almost never about sexism—they were about the hard work and challenges and joys and difficulties the contributors faced that they simply hadn’t had an outlet to write about because most bicycle-oriented publications are so macho and/or focused on professionalism and expert culture. So instead of having a publication focused specifically on “women’s issues” in cycling, it became a venue for writing that isn’t sexist or racist… it’s as simple as that.

SPS! Ever since I was a little hardcore punk kid, feminism and bicycles have gone hand in hand (at least for me). In your opinion, what is it about cycling that brings people passionately together?

EB: I love that you connect feminism, bicycling, and punk! It’s funny, because I always felt the same way and it didn’t occur to me that someone wouldn’t until I dipped into that sports side of bicycling. That’s where I first had the experience of talking with someone who was just as passionate about bicycling as I was, but for completely different reasons—like competition or athletic achievement or signalling of wealth—and who wore different clothes, biked in different places and at different times for different reasons, and even rode entirely different types of bikes. Meanwhile, I would show up to cover the race in my jeans and t-shirt on a clunky cargo bike and have to leave early to go to a meeting about organizing a traffic safety event. There are so many reasons to be into cycling that sometime the basic form of the bike itself is the only common denominator… well, that and the fears of what can befall you on the road. One of the things that amazes me about publishing—either a blog or print—is that it has so much power to bring these widely divergent groups together into common cause and help them see into each others’ worlds.

SPS! Historically, cycling was seen as an emancipatory technology for women. In an intersectional sense do you think the bike is still an emancipatory technology, helping people escape the implicit politics and unseen assumptions of their local infrastructure and built environment?

EB: In the 1890s, bicycling is famously remembered as an emancipatory technology... for upper class white women. The lesser known piece of that history is that this first golden age of cycling wasn’t pushed aside by the automobile—the craze ended when safety bicycles became widely affordable and “wheeling” was no longer a compelling elite pastime. So today, in an intersectional sense, I see bicycling as having emancipatory potential—and also the very real potential to reinforce social divisions. We’re seeing a lot of city leaders embrace bicycling for its enhancement and symbolism of gentrification—and we’re seeing a lot of pushback against that as well. At the same time, a very large number, maybe even the majority, of people who use bicycles as transportation in the US aren’t having their needs met by even the most bike-mad planners and advocates. The good news is that we’re seeing more and more bicycle groups that represent communities of color and marginalized neighborhoods, and it hopefully won’t be possible for them to be ignored by the powers that be for much longer.

Bikes

SPS! In your book Bikenomics you have the phrase: “Food, bicycling + changing the world are a great combination”. What other combinations of interests get you excited about the future?

EB: I get pretty excited about bicycles and dismantling capitalism.

SPS! Galina Tachieva in her book Sprawl Repair stresses the importance of accessible infrastructure, the return to walkable neighbourhoods and that these plans be integrated into policy at the city scale. How can activists of all kinds engage with their local municipalities to ensure they have a voice?

EB: By talking to and listening to each other, building strong coalitions, and putting the needs of the most disenfranchised among us front and center—that’s often the missing piece, but it’s how we win.

SPS! We just posted about worker-owned composting collectives that collect food waste by cargo bike. In Bikenomics you have a whole section on reducing traffic and pollution etc in urban areas by encouraging bike freight use to solve ‘last mile’ delivery problems. Are there any other collectives or businesses the solarpunk community should check out?

EB: I really enjoyed that post. It reminded me of a little kid in Traverse City, Michigan who had started a compost by bike business. Now he’s 10 and has a staff of other kids. https://carterscompost.com/ In my opinion, the most solarpunk bicycle operation out there is the loose global network of bicycle collectives / bike projects / bike coops. It’s this incredible ecosystem of businesses, organizations, and people just building bikes in a shed, all with the mission of helping people no matter what their income or background get bikes and learn to work on them for free or super cheap. A lot of them are led by the communities they serve and combine bicycle repair education with youth outreach, violence prevention, community activism, and other social services / social justice work.

Scifi

SPS! Biketopia! is the 4th volume in a now more-or-less annual ‘bikes and sci-fi’ series. How did the series get going and has the genre's popularity surprised you at all?

EB: It started as an issue of Taking the Lane. Someone asked for a fiction issue, which I didn’t love until it occurred to me that it could be sci fi. I loved science fiction and fantasy as a kid—it was really formative—and getting to work on it as an adult has been really satisfying and fun. It’s not the bestselling thing I do, but it’s definitely the thing that reaches the most people outside the “bike bubble,” and I enjoy it the most so that’s worth a lot. The first two volumes were published as zines, #3 and #4 were books that are being sold into bookstores, and I’m bringing them back to zines with #5 -- which has a call for submissions open till March 1, by the way.

SPS! Biketopia! will feature the solarpunk story "Riding in Place" by Sarena Ulibarri. From what have seen, what’s your opinion of solarpunk as a genre?

EB: I did a bunch of research on solarpunk when I was planning this book, and what I found is that the genre is still mostly underground—there aren’t a lot of comparative titles by mainstream publishers. So that’s exciting, it makes the discovery of new books and blogs more of an adventure, and it makes us pioneers to some extent. A year ago I would have predicted that we’d see a lot more of it in the future—you’d be wading through some dubious offerings by major houses by 2020—but now with Trump’s election it seems more likely that science fiction will take an even more dystopian turn. Solar panels feel so, I don’t know, Democratic.

SPS! Our Tumblr’s tagline is “At once a vision of the future, a thoughtful provocation, and an achievable lifestyle. In progress…” Do you think if everything we need to do gets done. Is there reason to be optimistic about humanity's future?

EB: Yes. I’m optimistic, but that’s mostly because I try not to have a fixed idea of what needs to happen for the future to be worthwhile. When I put out the call for submissions for Biketopia! it was for stories that were either extremely utopian or dystopian. And interestingly enough, the utopian stories were the ones that scared me the most. Reading them, I wondered: where were the non-perfect people? Whose stories weren’t being told? Whose labor built these shining solar structures? One thing I love about Sarena’s story, and the reason it opens the book, is because she gets into those complexities. There’s another story, by Cynthia Marts (she talks about it a bit in the project video), that focuses on one of the worst dystopias in the book, but if you read between the lines you can see it actually was conceived as a utopia by its founders, and probably still is by the husbands of the main characters. Meanwhile in all the dystopian stories, there are real heroes—scrappy fighters, people working together and finding commonality across their differences in order to survive and create their own life. And maybe this is fucked up, but I find that way more hopeful for the future of humanity.

Kickstarter: Welcome to Biketopia!

This is the 4th volume of the more-or-less annual Bikes in Space series.

Here are some dilemmas you'll get to face alongside the characters in these stories if this project is funded:

In the solarpunk future, will robots have rights, too?

When your health is closely monitored during a pregnancy, who gets to decide if bicycling is healthy or dangerous for your unborn child?

How do you survive the day to day in a community where you have zero freedoms, including freedom of movement?

When your agrarian society relies on bikes and now you're at war with the city where the factory is, how do you replace your broken spoke?

What is the secret behind some people's seemingly random plague immunity, and is it okay for them to take your bike?

Is the sexy stranger who rode into your desolate desert oasis a man or a woman or does it even matter?

The book also contains reviews of more science fiction books, stories, and TV shows.

(This project will only be funded if it reaches its goal by Thu, Mar 2 2017 4:48 PM GMT.)

(via Biketopia: Feminist Bicycle Science Fiction Stories by Elly Blue — Kickstarter)

#solarpunks#solarpunk#interview#zine#biketopia#bikenomics#elly blue#kickstarter#microcosm#publishing#zines#bikes#feminism#scifi#story#book#crowdfunding#science fiction#sps!

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hyperallergic: Louise Bourgeois: An Unfolding Portrait, a Conversation with Curator Deborah Wye

Louise Bourgeois, “Spider” (1997), steel, tapestry, wood, glass, fabric, rubber, silver, gold, and bone. 14′ 9″ × 21′ 10″× 17′, collection The Easton Foundation (© 2017 The Easton Foundation/Licensed by VAGA, NY)

In 1982, as a young curator at the Museum of Modern Art, Deborah Wye organized a retrospective exhibition devoted to Louise Bourgeois, who was then 70 years old. It was the museum’s first one-person survey of a woman artist in well over 30 years. Later, Bourgeois donated an archive of her printed work to MoMA and, in 1994, Wye organized an exhibition of Bourgeois’s prints to accompany the publication of a catalogue raisonné. Over the next 17 years, the artist, who died in May 2010, produced a vastly expanded body of prints, for which Wye has now edited a comprehensive online catalogue. The exhibition Louise Bourgeois: An Unfolding Portrait, on view at MoMA until January 28, 2018, celebrates that publication.

Wye, now Chief Curator Emerita of Prints and Illustrated Books at the Museum, and I are standing in the museum’s yawning Marron Atrium, where an immense spider sculpture in the center (with a smaller one high up on the wall), and a panorama of large-scale prints, offer a somewhat intimidating introduction to the exhibition, the balance of which is installed in the third-floor Edward Steichen Galleries. Wye organized the show and wrote the accompanying catalogue, which provides an expert overview not only of Bourgeois’s prints and artist’s books but her work as a whole.

* * *

Deborah Wye (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

Christopher Lyon: We’re standing beside “Spider” (1997), which seemed like a good item for orienting ourselves biographically. It is a steel sculpture of a spider, almost fifteen feet tall, whose eight legs surround a circular cage-like structure. Hung on its walls, attached to several frames propped up inside the structure, and draped on a chair at the center of it, are fragments of faded and tattered tapestry. This work is one of the series of Cells that Bourgeois created over the last two decades of her career.