#he’s the first one to point out the goats were blameless too in the job situation

Text

ok so the thing is, the kiss really was the best way crowley knew to convey his feelings to aziraphale because nina and maggie were right, they do talk but they never say what they mean.

but that doesn’t mean they don’t understand each other, at least to a certain extent.

and crowley knows aziraphale

he knows that he loves books and plays and the stories made by humanity. he watches his angel learn magic the human way and finds out he learned french the human way and knows better than anyone how much he loves human food. he throws a ball to get nina and maggie together because that’s what the humans in jane austen novels would do.

crowley knows that aziraphale romanticizes humanity, loves the drama and the stories and every little thing that makes humans human.

and what could be more human than a desperate kiss asking someone to stay

#good omens#and don’t get me started on crowley#crowley loves humanity too but it’s more than that#crowley loves the universe#crowley loves humans but he also loves the earth and the animals and the nebulas#he’s the first one to point out the goats were blameless too in the job situation#he loves every part of the creation that he helped build#and that’s why he questions it every time god wants to destroy all of their beautiful creations#because why make this beautiful world just to destroy it#in conclusion: aziraphale loves the world and crowley loves the universe and they both love each and i’m always in pain#i definitely went off on a tangent there but i just love them so much

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Re-watching the Job episode today and...

Throughout the long course of their relationship, Crowley challenges Aziraphale. He does this from their first meeting in heaven: "Why not put the Earth in the middle of the universe so the view's better."

He does it again in the garden of Eden. "Wouldn't it be funny if you did the wrong thing and I did the right one."

And again at The Flood: "You can't kill kids."

And with Job, too, although in a slightly different way. This time it's about what Aziraphale believes is right, yes, but I feel like for Crowley at least, he's also pushing Aziraphale's limits. Not so he falls or anything. Crowley never wants Aziraphale to fall. He knows it would utterly destroy him.

No, Crowley's trying to find out how evil, exactly, Aziraphale thinks he really is.

Of course, Aziraphale made reference to it before. "You're a demon." He believes evil is a demon's natural state of being.

What Crowley wants to know is whether Aziraphale truly believes evil is Crowley's natural state of being.

So, just like Satan and God test Job, Crowley tests Aziraphale.

"I killed those goats."

"I long to destroy the blameless children of blameless Job."

When Aziraphale says: "You're perfectly safe." And Crowley says: "Are you sure, angel?"

And Aziraphale is sure. There's never a point when Aziraphale is unsure, never a point when he thinks Crowley wants to go through with it, never a point when he thinks Crowley is evil.

So, Aziraphale passes Crowley's test.

But this, of course, is a huge contradiction in Aziraphale's worldview. If demons were all innately evil then Crowley, by definition, would have no qualms in following through hell's orders. But Aziraphale can never quite manage to grapple with that.

To Crowley, it's confirmation that they can be on their own side someday. He doesn't have to be lonely anymore. He thinks Aziraphale, like himself, doesn't need heaven or hell to dictate morality to him, that they know what is right and can work together to ensure nobody gets hurt amongst all heaven and hell's scheming.

The tragedy is that to Aziraphale, Crowley protecting the children is only a confirmation that the angel he used to know is still there somewhere deep down, that Crowley is unchanged from the fall, and that if heaven would only understand, he could be an angel again because he did good. And goodness and divinity are inexorably tied for him. Even though he acknowledges that there's shades of gray, he can't understand having one without the other, not fully.

And that's the central misunderstanding between the two of them.

That's how you get the ending we got.

Crowley: thinking that Aziraphale has learned at least a little bit to think for himself.

Aziraphale: thinking Crowley has aspirations of redemption that Crowley has never striven for, because Aziraphale hasn't yet unpacked all his biases.

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

The disappointment on Aziraphale's face when he realised Crowley wasn't talking to him when he said, "Look at you, you're gorgeous!"

Gosh the jealousy!

Hello everyone! Back after watching S2 of Good Omens.

Here are my thoughts:

1.)

*live slug reaction*

On a serious note, I love how quickly he comes back. He always does.

Love how Crowley and Aziraphale are always on the same side, even though their methods are different. This is why I love them together.

Also the show's humour is still intact lol:

The moment when Crowley acts all tough and devilish™ and says, "I want to destroy blameless Job's blameless children, just as I destroyed his blameless goats," then Aziraphale realises the goats were just hidden in plain sight, disguised as birds; is my favourite. Even Aziraphale can't contain himself:

Looks like he wants to jump at Crowley right now.

It might be a cliché but I love it when a character acts evil but is actually a loving person lol.

3.) When 'Buldad-the-shuite' asks Sitis to reach for Job's robes to procreate, she goes for Job's crotch at first before going for the three ribs. 💀

Also, love this dialogue exchange:

A: What am I?

C: An angel, who goes along with Heaven, as far as he can.

A: That sounds...

C: Lonely? Yeah...

A: But you said it wasn't!

C: I'm a demon. I lied.

It's so meaningful. It brings out the similarities and differences between Crowley and Aziraphale effectively. The main difference is that Aziraphale lacks self-awareness. He still wants just the same things as Crowley. Doesn't want to admit it, though.

Also, I was so glad to see the God-narrator back in Episode 2. I was missing her in the first one. Wish she were there for the rest of the season too.

3.) Loved David Tenant's acting during the whole scene where Crowley downs the bottle of Laudanum. Crowley is kind, but he isn't ready to hear that yet.

The thing is, this season was more character-driven as compared to the first one. None of the Armageddon or the Antichrist thing - only Crowley, Aziraphale, and their relationship together: that was the main focus here.

I liked both seasons equally, just pointing out the contrast here. Right now, only who these two are and what their relationship is like are the two important questions here.

Season 2 has been highlighting this time and again that Crowley has a better clarity of everything as compared to Aziraphale about what he wants in his life, even though he's shit at communicating about it.

Aziraphale is shit at communication too, and he doesn't have that kind of clarity like Crowley on top of that. He does want the same things as him, but he's in denial.

I'll have to continue this to one or two more posts because of Tumblr's 10 images limit in one post.

Bye!

My Season 1 ramblings.

#good omens#crowley#aziraphale#live blogging#aziraphale/crowley#aziracrow#ineffable husbands#good omens season 2#personal ramblings#sort of a meta#meta#screencaps#shitpost#not exactly#enthusiastic fangirling lmao

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kaneki, the Oggai, and...Postmodern Neo-Classical Tragedy?

So people have been laying in to Kaneki for killing the Oggai, and I think Ishida too wants us to view this as a serious moral line he’s crossing here. But while obviously killing children is a bad thing, I want to ask why everyone’s blaming Kaneki so unforgivingly when Touka, Yomo, Naki and Miza were killing Oggai left right and centre in the preceding chapters and the morality of that wasn’t questioned in the slightest - it was even considered badass. I’ve heard it said that Touka and Hinami won’t forgive Kaneki for killing the Oggai because they’re children, but Touka’s already killed a bunch of them and Hinami made no objection to that.

I’ve always thought Kaneki gets judged way more harshly than other characters in the fandom for his actions. Kaneki killing humans is given a lot more outcry than any of the Ghoul characters, who have been doing it since before the series even started, and while certainly not sinless, Kaneki is actually a lot higher up on the moral chain than most of the characters in the series. He’s breaking boundaries now that the other characters broke ages ago, but because it’s occurring to him now rather than in the past, it’s negative development rather than positive; so he gets judged more harshly now than, say, Tsukiyama was at the start, despite the fact that Kaneki’s moral fibre is still way stronger now than Shuu’s was back then. But the main reason for Kaneki’s severe treatment, I think, owes to the story’s genre - because it’s a tragedy, we’re constantly looking with extreme scrutiny for Kaneki’s fatal flaw and the justification for his impending downfall.

But the slaughter of the Oggai was an entirely different beast to something like, say, Anakin killing the younglings in Star Wars. The younglings were innocent and posed no threat to Anakin. The Oggai were going to capture Kaneki and most likely keep him locked up in a tube in the same manner as Rize for the rest of his life - not to mention killing all his friends and loved ones. I really can’t blame Kaneki, or any of Goat, for acting in self-defence.

@hamliet very eloquently makes the argument here that Kaneki’s unforgivable action was allowing himself to end up in this situation in the first place, but I would counter that by raising the point that even if he didn’t kill the Oggai in this exact scenario, he and his army would inevitably have to kill them at some point, simply because they’re the opposing army. Far more so than Kaneki, the people really to blame for the tragedy of the Oggai are Furuta and Kanou for weaponising children in the first place. Goat really didn’t have a choice here - Furuta forced their hands, as an Author of Tragedy well might.

Additionally, we’re never given any reason to sympathise with the Oggai beyond the simple fact of their age. They never show much human emotion beyond crazed bloodlust, which makes it pretty hard to see them as people at all and not caricatures, or to honestly shed any tears for them - very much unlike Shio and Rikai, killed at their hands. With Yamori, we were told about the torture he went through and we pitied him even while despising him. Maybe if we saw a child go through the process of Oggaification, or if we saw them playing around like normal children in their spare time, I might be more shocked at Kaneki’s behaviour here; but as it is, if we were meant to feel sorry for them, it’s not very effective.

I feel much more pain for this perfectly innocent, nameless man who got his head sliced open by Kaneki. But even Kaneki’s dragon rampage is not his fault; he’s non compos mentis, driven mad by his kakuja, pushed to that state by the desire to survive - a desire that is completely natural and justified, and if it weren’t, then Ghouls would have no right to exist at all. How could Kaneki possibly have predicted that this is what would happen if he came back to the base? Worry for his wife, child and friends is hardly a fatal flaw that justifies his transformation into a city-terrorising monster - and indeed, it was his actions that saved their lives...at least for now.

I can’t in good faith blame Kaneki for this outcome. So rather than trying to find tragedy in the flaws of the protagonist in the modern understanding of the genre, here it might be better to look to the classical definition of tragedy. In Aristotle’s Poetics, he argues that tragedy should serve the function of evoking pity and fear in the audience.

“The one [pity] is to do with the man brought to disaster undeservedly; the other [fear] is to do with [what happens to] men like us.”

The word hamartia didn’t refer to a fatal flaw as it is currently understood nowadays, but rather just a mistake. Here his mistake was going back to the base, a decision which, while rooted in his character, did not spring out of a flaw. The mistake is supposed to be blameless; it’s important that he is brought to disaster underservedly, just like with Rize.

Aristotle uses Oedipus Rex as his prime example for tragic format, whose hamartia was killing his father - he didn’t know it was his father, and in Ancient Greece it was considered fair enough to kill a stranger for splashing you with dirty water. Modern readings try to point to Oedipus’ rage or pride as the reasons for his downfall, but the way Aristotle read it was that Oedipus didn’t deserve his downfall at all. The purpose of tragedy was to remind us of our mortal weakness in the face of the power of the gods. The futile struggle of an individual against the author of his existence.

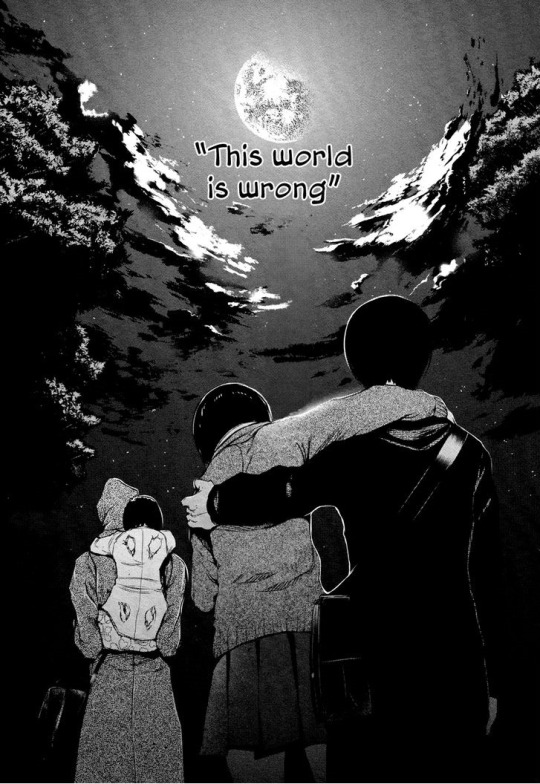

Kaneki suffers like Job, clay in the hands of his maker, nothing more than a penstroke of the tragedian.

He inspires our pity in waves, stumbling upon this tragedy by sheer misfortune. He tries to rationalise it by attributing the blame to himself with arguments that he hasn’t been strong enough, but that’s just a man trying to understand a classically tragic world through the lens of modern tragedy, and his efforts to become stronger only lead to greater tragedy.

He inspires our terror by just provoking the thought that all Kaneki has gone through could have happened to any one of us in that world. Indeed, Kaneki’s initial character design is meant to look as much like a typical Japanese teenage boy as you can get, and most readers of the series can relate to Kaneki’s shyness and bookishness. Like your typical everyman, Kaneki doesn’t care for much more than his loved ones. He hasn’t received this lot because of ambition, or jealousy, or wrath - just because of the divine will of the world he lives in.

Now, TG doesn’t fit with many of Aristotle’s other rules for tragic format - it has unity of neither time, place, nor action (and a good thing too, if every tragedy followed Aristotle’s format they would get very boring very quickly) - but I think this outlook is definitely worth considering, given the number of times the words “This world is wrong” are repeated throughout the series. If this holds true, then that would make Tokyo Ghoul not just a tragedy, but a Postmodern, Neo-Classical Tragedy. Which is a cool enough concept in itself, but if there’s still room for hope - if Kaneki can yet triumph over his genre, and man can at long last defeat the gods - then TG would truly be a landmark in the evolution of Tragedy. Recent events have shaken my optimistic outlook a little, but whichever direction it goes from here, it’s still a literary tour-de-force of phenomenal proportions.

#BAM LOOK AT THAT ***UNIVERSITY ENGLISH KNAWLEDGE***#i've been to two weeks of lectures and i think i'm manga aristotle lol#tokyo ghoul#tg meta#ken kaneki#oggai

217 notes

·

View notes