#force planning

Text

"What Should It Look Like?" Part I: The Big Picture (OLD ESSAY)

This essay was first posted on November 10th, 2021, and is the first in my "What Should It Look Like?" series that I'm still working to complete to this day (lol).

The jist of the "What Should It Look Like?" series is assuming that (eventually) get some kind of more equitable, democratic socialist society in America, is what kind of foreign and defense policy we forge from that and what kind of military force we build to carry it out and how its different (and in some cases, not that different) from what we have today. This first entry established the overarching assumptions for the series before the following segments drill down into the different military domains and spheres of warfare.

(Full essay below the cut).

Everyone has their weird little hyper fixations or odd things that are soothing or enjoyable to think about but that make other people arch and eyebrow. For me, a big one of those is thinking about military structures and organization. That’s been the case for me thinking about things both in real life in regard to my actual job or my work here, and also as a hobby when I think about writing stories or doing worldbuilding or what have you. It’s just my thing.

Inevitably, over the past year or so as I’ve approached the topics of war and military matters from a left perspective, I’ve found myself wondering to myself or talking with like-minded folks I know about how existing military structures and organization should be changed, replaced, or just killed with fire under a more just and equitable system. It’s something I’ve wanted to write about for a long time and have hinted at in bits and pieces before, but have continuously had to push back because inevitably some new crisis or conflict emerges that I feel compelled to write about while the iron is still hot. Finally, I decided there is no time like the present and I should at least get started on it.

This essay will be the first in a series of essays on how I think the United States Armed Forces should be structured and organized if it were under a government and overall socioeconomic system that didn’t make me want to crawl into a corner and cry several times a day about how we are living in a dogshit timeline. I knew from the beginning that there was no way in hell I was going to be able to cram everything I wanted to write about into one essay if I wanted to do it all justice, so I’ll be dividing up this study across about a half a dozen parts or so in the coming months. It will likely be interrupted by current events here and there, as with how things are currently going in the world, I don’t expect the madness to slow down anytime soon. But I’m going to keep fitting in chapters of this series where I can until its done.

With that in mind, I felt a fitting place to start in the first chapter of this series is to address the big picture items that you need if you’re going to design – or re-design – a military force. Once we get that out of the way, in the ensuring chapters we’ll look at each of the military services or major components of the Joint Force and the ways in which they would change to fit a different strategy and overall mentality of not only the military, but the people that it serves. So, without further ado, let’s get started.

Strategy: Let’s Try Not to Be Dicks

If I learned one useful thing about national security in two very expensive years of graduate education and more than a few years working in the field, you can’t structure and build a military force without first thinking of a strategy (I mean, you can, but it probably will fail or not be very useful in the end).

Strategy is the point from which everything else flows in military thinking, laying out the main objectives that a country or entity seeks to accomplish, as well as the overall big-picture approach to achieving them. Once you have a strategy, you then need to visualize some of the most likely scenarios that may occur in the course of executing it. Then, from there, you can actually start thinking about how you will plan out and then develop and build an effective military force to fight and succeed in those scenarios in service of the strategy (and most importantly for a different mentality about this, the people it’s meant to protect). I’m simplifying and abstracting this process a lot for those of you who don’t live among the DoD PowerPoints like I do (don’t cry for me I’m already dead) but that’s the basic idea at the end of the day.

So, in a better world, what would be the main U.S. defense strategy?

In contemporary times, every U.S. administration will put out a series of different defense and security related strategies. These include a National Defense Strategy (NDS) that hits on the high level national security objectives, a National Military Strategy (NMS) that explains how the military will implement the objectives laid out in the NDS. For purposes of our conversation I’m gonna kinda mesh them bother together (I don’t really see why they need to be separate anyway).

The objectives listed within the NDS range from straightforward and obvious to very much open-ended and murky (which leaves a lot of room open for interpretation), as well as ranging from practical and sensible to openly imperialistic. We can see this in the most recently published NDS from the Trump administration in 2018 (the Biden administration is still working on their replacement, though they’ve thrown together some interim guidance). For example, “defending the homeland from attack” has been in every National Defense Strategy in recent memory and seems both straightforward and like something we should be doing. Meanwhile, “sustaining Joint Force military advantages, both globally and in key regions” could be taken to mean a lot of things to anyone. And don’t even get me started on “Maintaining favorable regional balances of power in the Indo-Pacific, Europe, the Middle East, and the Western Hemisphere.” Oof.

So, in the better world we hope for, where President Leftist has just been elected with his/her/their big lefty Congressional majority or whatever, what should the objectives be? I’m not going to list out a dozen different objectives or more like there usually is in an NDS because I could spend days pacing around my room just trying to figure out what those should be and frankly a lot of those will change reflective of the time a strategy is written in. But what I can do is think of a few, key objectives that will likely be enduring throughout time and offer some a persistent reference point from which other objectives would come and go in future iterations of the strategy.

To identify a few key objectives, I think back to some of my earliest essays and the main themes that have persisted throughout them. Fundamentally, as a defense strategy, I feel that it should actually be truly defensive. Moreover, it should not seek to only defend territory and certainly not be intended defend nebulous “interests” abroad. At its core, the strategy should be about defending people and the means that they need in order to survive and lead happy and fulfilling lives free from fear. We should be seeking to do this not only in our own country, obviously, but in other countries too. Essentially, wherever a people come under unprovoked, unjustified, uncalled for armed aggression, we should be prepared to offer assistance and to provide it if the people under attack accept our help. In past essays I have referred to this more politely as the “Don’t Start None, Won’t Be None” strategy, and less politely as the “Fuck Around and Find Out” strategy (choose whatever one you’d rather say among friends, I’m gonna go with the saltier one because of reasons).

More than anything, this would be a strategy not about “interests” but about people and principles, chief among them being the principle of solidarity with people around the world. As part of that solidarity, we should also support those throughout the world that want to live under a better system. I should be careful to say this should not involve invasions, occupations and regime change, nor should it involve working to incite or provoke rebellions, uprisings and civil wars through covert action and manipulation. But what I do mean is when a people in a given place decide that they have had enough, are denied peaceful ways of enacting change for the better and are left no choice but to turn to force of arms against forces of authoritarianism and fascism in order to create a better more just system to live under, we should be ready and willing to support them in their struggle. The choice to embark on this path must lie with the people in question and the support we offer should be aimed at enabling them to achieve what they want instead of dictating to them how and what they should be doing.

That same logic should apply to supporting nations and peoples across the globe in a “steady state” peacetime environment. The United States and other countries often pay lip service to the idea of allies, but only when allies align with our interests. Instead, we should be supporting allies based on shared principles. We should be supporting those with similar systems who value the same principles we do – the principles that often also get paid lip service to but would be great if we actually lived up to them. Principles like true democracy and self-determination, justice in every sense of the word and for all peoples, freedom – not simply to do certain things, but freedom also from want, fear, privation, etc. We should be supporting other nations, not only by pledging to stand beside them in battle should they ever request it, but also by doing our best to help them stand on their own two feet and defend themselves so it may not be necessary for us to come to help in the first place. We shouldn’t be keeping allies on a short leash or turning everything into a quid pro quo situation of “what can you do for me”. We should be helping them because it’s the right thing to do (there’s that whole “solidarity” thing again).

This whole strategic concept is kind of ironic because I realized after the fact that it reminds me a lot of the realist (realist in the I.R. theory sense) concept of “offshore balancing” that’s been around for a while but really came into vogue in the immediate post-Cold War period (I’m sorry to link Wikipedia here but I really cannot find a good source that isn’t behind a paywall, because my field is truly inclusive and welcoming to all lmao). Under offshore balancing, a great power would maintain a sort of informal federalist empire and avoid deploying its own military forces forward to the maximum extent possible by providing certain key actors in regions of interest (ex: Europe, Southwest Asia, Northeast Asia) with economic and military support as long as they act in accordance with the great power’s interests. Under offshore balancing, the great power at the epicenter of the empire “passes the buck” to its local agents to deal with regional conflicts, only intervening itself when it absolutely has to in order to minimize the cost to itself.

Now obviously this is extremely fucky and imperialistic almost by admission. But what we’ve come up with here is actually fairly similar in structure, but completely different in purpose. Again, the key here is not interests, but principles. The state at the center of this web in our system is not trying to act as the heart of an empire – in fact, it would be trying not to be the center of a web at all. It would be supporting local powers to better defend themselves because that would benefit everyone involved in terms of safety and stability and would be doing so without preconditions (aside from maybe encouragement to continue on with reforms to make a more free and fair society if it is a country that is still in a transition from a previously more authoritarian existence). The goal would be to create a series of interlocking hubs and spokes of like-minded states and peoples that are supporting one another in being independent and self sufficient in their defense, but also stand ready to intervene on their behalf should that become absolutely necessary. In that case, the strategic concept supporting the Fuck Around and Find Out overall strategy is less Offshore Balancing and more Offshore Solidarity.

Yes, I know way too much international relations theory for my own good. How could you tell?

Remember the ‘90s?

Ok, so we have a strategy. But we can’t get to the fun stuff of tanks, jets, ships, brigades and etc. just yet. Because before we can get to those details, we need to think about what executing this strategy would mean in practice in a broad way. We need to think about what the force as a whole would need to do in order to carry out the key points of the strategy before we can think about what it would need in terms of system and units to support it.

An important thing to keep in mind when attempting to build a force is no that no military force can cover every single potential military eventuality you may encounter. It’s just quite simply impossible to think of every possible conflict you may find yourself in, and even if you could, you wouldn’t be able to be fully prepared to excel in all of them. Even the United States military now, spending more money than God on its capabilities, isn’t capable of winning everywhere all the time at everything (as this summer probably made painfully obvious). This is where scenarios come into play, forcing us to think about the most likely and plausible instances in which we will find ourselves on the battlefield. By necessity and for practicality’s sake, you’re going to end up having to make trade-offs when building a force, assuming risk in one area in order to be stronger and more effective in another. Obviously, these are tough choices to make, and will depend a great deal on the types of situations you anticipate your force ending up in. So, that begs the question, under this hypothetical strategy, what do we see our force doing?

We’ve already fleshed this out some in the strategy itself – as well as in past essays – but we can add a bit more granularity here. The main recurring scenario, as I’ve described before, that seems to come to mind when I’m thinking of the Fuck Around and Find Out strategy is when a hostile nation (we’ll say Country A) launches an unwarranted attack on a neighbor (Country B). For purposes of our planning, we’ll assume this attack is going balls to the wall and Country A has the intent of fully invading, occupying and forcibly integrating Country B. We’ll assume also for the sake of our planning that Country A isn’t a small country with a bottom tier military, but at least a regional power with a fairly robust military capability across multiple domains.

Thankfully for my own sake here, I don’t have to work from scratch with visualizing this, because some of this work has been done for me before in a far-off time known as the “1990s.” Several studies were done on this type of war in that mystical hyperpower period of the “end of history” that occurred between the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the terrorist attacks of September 11th, 2001 when the U.S. military was trying to find out what the fuck to do without itself in the coming decades. One such study undertaken by the RAND Corporation from 1993, examined the changing role of airpower in what they called “major regional conflicts” – with their primary example being a hypothetical Gulf War style conflict in Southwest Asia against an abstracted Iraq or Iran sized adversary (at least they had the good sense in this study to make it abstract or that potentially could have been awkward later on down the line let me tell you).

While it pains me to say this, a Gulf War style scenario – both the actual one and the one outlined in this study – is a pretty good reference point for what we want to do under this strategy in terms of actual operational execution. Now, obviously, as good leftists, we want to do this without helping out several corrupt and authoritarian oil-rich absolute monarchies in the process (and the oil companies of course) and also try to commit little or no war crimes as we do it (I would hope). But in terms of the operational goals and execution, it’s a pretty decent blueprint. Now, things we’ll change for us looking out into the future in terms of the exact capabilities and systems brough to bear, and its exact application would change based on the location and adversary involved, but we’re talking about the same basic thing: enemy invades country and occupies it, we move in and liberate the country and forcing the enemy out. Politics aside, it’s a pretty damn good framework (ok that’s the last of my praise for now I swear).

Now, assuming you want to halt and roll back the invasion that is occurring before the enemy can complete it, a number of pieces are required and need to fall into place at certain times. RAND’s scenario – as does mine – assumes no US forces being forward deployed when the attack occurs (though for some reason ‘no’ doesn’t account for an entire fucking carrier battle group, which they consider ‘modest’, but whatever I guess – I’m going to assume ACTUALLY nothing). This means right off the bat that air forces – as they tend to be in modern warfare – are crucial. Air forces are the forces that will be able to reach the war zone the fastest and have the most immediate impact. This includes – but is not limited to – fighters that establish the air superiority that all other functions will occur under the umbrella of, attack aircraft to work to slow down or stop enemy ground advances (and eventually assist friendly ground forces in a counter-attack), ISR collection aircraft to get a better picture of the situation, and of course transport aircraft bringing in the first waves of troops and equipment to support allies and assist in stopping the enemy advance and establishing a defensive line until heavier forces arrive.

This leads into the types of ground forces you’ll need as well. Obviously, you’ll need some forces that are light enough to be airlifted quickly into a conflict area and achieve enough mass and have enough capabilities to be able to work with local forces to stop – or at least slow down – a numerically superior enemy advance. However, you’ll then need to be able to bring heavy mechanized and armored forces to bear that will pack the firepower, protection and mobility necessary to push back enemy forces out of friendly territory. These forces will need to be backed up by long range fires, as well as all the less sexy aspects of warfare, including logistics, medical, and other support that you don’t usually see in action movies and video games.

And of course, if you want to move heavy forces into the theater, you’re going to need sealift (not unless you want to be flying in tanks two at a time on constantly running transport flights, which is not ideal). Even if the country you’re trying to help is landlocked, if you want to get in the bulk of the equipment and materiel you’ll need to fight a major war – which is all heavy as fuck, it’ll have to come by boat and then move overland. That means, in addition to sealift capacity, you’ll need some naval forces to make sure said sealift gets from point A to point B in one piece – especially if the enemy you’re fighting has a navy of their own. If the opposition does have their own navy, you’ll also need your own navy to ensure the enemy can’t use their own navy to launch attacks on your forces in all domains. Even if the enemy doesn’t have a navy, naval forces still bring another means of delivering long range fires on target (for reasons I’m about to get into).

Long-range attack from the air and sea becomes all the more important if the enemy has a robust anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) network of anti-air, anti-ship and surface-to-surface missiles, attempting to block you from bringing in forces to the fight. That importance is further accentuated if the enemy succeeds in the invasion and this operation becomes a war of liberation to free the ally under occupation, with the enemy having time to move their A2/AD assets into the occupied territory to solidify their gains. This is also another reason why air forces are so important in the same regard. Firing long range missiles from ships and planes outside the “bubble” of A2/AD may end up be one of your only ways of being able to “pop” the bubble or make a crack in the dome, allowing you to flow forces in to help your ally. That, or finding ways to get inside that bubble without your enemy being none the wiser. It’s a tough nut to crack.

But I’m starting to get ahead of myself here, as this is all stuff I’m going to talk about as I get deeper into the different domains and services in subsequent essays. There’s also lot of other capabilities I haven’t mentioned because they don’t necessarily have to be flowed into the theater (like space assets, cyber, information warfare, and etc.) that will all play a critical role in any campaign as well, and they’ll be getting their due later too. I also kind of hand waved all the support elements that would be necessary to focus on the sexy, pointy things, but rest assured they’ll be covered as well and are crucially important. But I wanted to first give you a big picture idea of the kinds of key things you’d need in order to carry out this Gulf War style campaign to stop the invasion of a friendly country, roll it back, and also destroy enough of the enemy’s capabilities to ensure that they wouldn’t be able to try that shit again for a while (fuck around and find out, after all).

The Stage is Set and the Game is Afoot

Well, we have the beginnings of a strategy and at least one supporting concept for it. We also have a rough idea of what I think would be a pretty likely scenario that would be carried out under the auspices of that strategy. I think we have a ball game, folks.

Now, this isn’t the only scenario that could happen, but as I said before you can’t plan for everything and this is also only our first foray into this adventure. What I tried to do here was throw out something that seemed like it would be the most plausible and also fairly stressing. There are a few other edge cases that may occur. I’ve mentioned before the possibility of intervening in an internal conflict to prevent a genocide – that may bring some unique difficulties. Likewise, you could fight a conflict like the one I laid out against an even more powerful nation. But I only have so much space to work with and so many hours in the day, so I just threw out what seemed like a plausible, believable scenario – both in the past, but also under the hypothetical system that we’re imagining here.

I also want to point out that obviously this isn’t going to be as robustly researched and analytically rigorous as a well-polished research report or book. Honestly? I’d love to do something like that and maybe someday I will. But between my day job and my other hobbies and responsibilities, I’ll need to stick a pin in that for now and reach for what’s possible. Rest assured I’ll do my best not to talk completely out of my ass and back up my assertions with what I can find in terms of supporting research. Some folks will obviously disagree with my conclusions and that’s fine. I welcome some constructive feedback. In fact, that’s the only way things like this work. When you just get one person – or several succumbing to groupthink – working on these sorts of things and carrying them out, well, that’s how you get just about every U.S. military and foreign policy failure since ever in the history of ever. So, I look forward to feedback from friends and comrades as I continue on in this series.

Unless you’re just gonna be a dick about it and lecture to me about how drones are going to solve everything or whatever. In that case: lol lmao.

Well, I think I’ve pretty much run out of gas on this for now. Next time I return to this series, we’ll be starting to get into what each of the services or key domains of warfare would need to look like to make all of this happen – starting with everyone’s favorite green machine: the Army. Until then: stay safe, stay alert, and remember to log off once in a while.

#essay#War Takes#War Takes Essay#leftism#leftist#socialism#democratic socialism#international relations#IR#national security#national defense#international security#foreign policy#foreign affairs#military intervention#war#defense planning#defense policy#force planning#internationalism

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

cat's cradle

[this is from the team dark zine i made! you can find it all here]

#this was not a page i planned to have in the zine‚ i was like 90% done with everything but wanted to add something from forces#and then i finished this whole thing in like sub 3 hours which is CRAZY fast for me#oh sonic forces episode shadow you really could have been something. you really could have#fern's sketchbook#sth#team dark#rouge the bat#shadow the hedgehog#e 123 omega#infinite the jackal#🦔🦇🤖

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

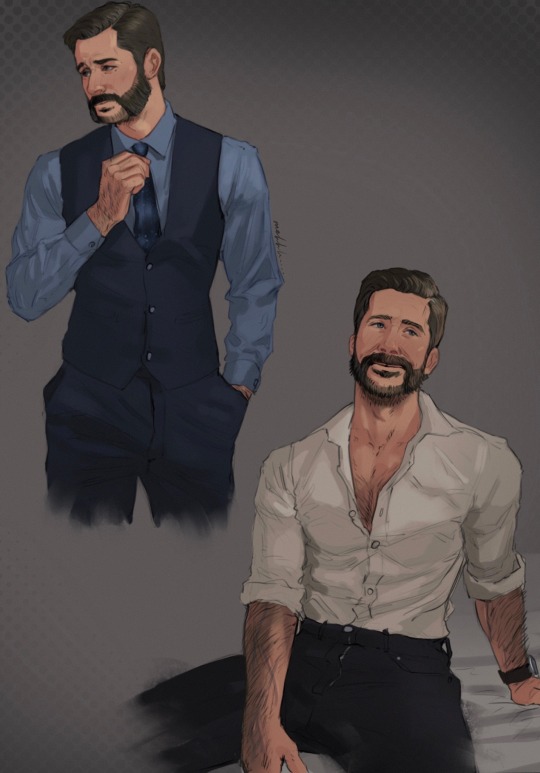

Professor Price | 1/10

Just my vision on how prof!Price from @guyfieriii’s series would have looked like

#i was kinda blushing while drawing this…#yes I plan to draw 10 drawings of him#yes longer graying hair with some classy hairstyle bc why not#it looks yummy on him#i don’t care that price is canonically 37#hes 40-45 for me#hes an old sexy man#and that is exactly how i like to draw him#captain john price#captain price#call of duty modern warfare 2#call of duty modern warfare#call of duty#john price#john price x reader#professor price#captain john price x reader#modern warfare#task force 141#call of duty fanart#captain price fanart#barry sloane#barry#love him#mw2022#call of duty mw2#mw2 x reader#price x reader

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

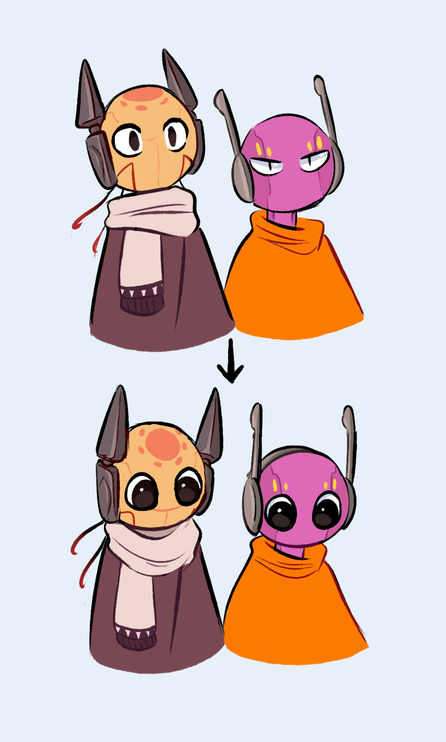

Experiments with pupils and mouths that devolved into shenanigans :)

#you can really tell I was having a normal one when I drew these#I like many of the pupil experiments but don't really like mouths on my iterators#i've seen some people do mouths on itties well though#...really enjoyed noisy cat spearmaster with a mouth tbh#no plans on changing how i usually draw things rn. this was just for fun#Sometimes I miss having pupils and mouths to work with (on slugcats and itties)#Not having either on iterators can be a unique challenge that forces me to practice my body language more#which I like drawing anyways so it works out#antennae are suuuper fun to use for expressions too#rain world#flickerdoodles#art#group pic

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Palestinian freedom fighters breaking out of Gaza and reclaiming their occupied territories. They’ve taken over israeli tanks and have chased out the settlers that were on that land. They’ve launched rockets everywhere and the iron dome has failed to intercept. This is about to mark a momentous event in history.

From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free.

#free palestine#it feels so surreal and so shocking#there’s so much hope but so much fear#you just know they’re about to retaliate with the genocide they’ve been planning for years now#i fear for my palestinian brothers and sisters but this is so fucking huge#they tore down part of the barbed wire fence!!!! the people of Gaza are breaking out!!!!#god there’s so much more on twitter but i beg if you look do NOT look at non-palestinian sources#they’re twisting the narrative as if this isn’t retaliation for 76 years of torture#as if the israeli forces and settlers didn’t kill 4 palestinians yesterday alone#as if they haven’t killed nearly 300 palestinians this year alone#do NOT let the media trick you into thinking anything after will be a retaliation to an attack Palestine started#PALESTINE is the one retaliating#also if you’re gonna come in here with both sides or whatever sincerely block me and lmk so i can blokc you#they’ve already out out statements to leave children and the elderly alone so any middle aged fuckers are free to kill :)#which is fine since they’ve likely killed hundreds if not thousands of their friends and family and neighbors anyway#tag: important#fuck israel#gaza#tag: october 7 2023

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

An interesting “side effect” of the canonization of the “classic era” meaning “younger era” is that the classic era now reads as “cute fun times” before the core cast became teenagers/tweens and things got super, super complicated.

Because the characters are “younger,” there’s an air of “little rascal innocence” to everything they do now. The new releases like Mania and Superstars now feel like little throwbacks to the young heroes just learning how to work together and make a difference in the world.

I don’t think this is a bad thing at all.

#this is actually something I’ve headcanoned for years#seeing it reflected like this in canon is actually pretty strange#but welcome#I genuinely think it makes much more sense#it reminds me a lot of the anime erased if anyone knows what that is#this was obviously never the plan from the beginning. Sega certainly just expected us to be like#‘oh it’s the same thing but pretend that sonic had green eyes the entire time’#but of course pontac and graff happened#and generations happened#and forces happened#and suddenly they had way too many gaps to fill#so all things considered I have no issue with this retcon#it fixes a lot of problems tbh#sonic the hedgehog#sth#sonic#amy rose#tails the fox#knuckles the echidna#classic sonic#sonic frontiers#sonic mania#sonic superstars#core four#sonic core four#miles tails prower

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Not all who wander are lost.

Some who wander, however, are extremely, extremely lost.

#note: this is a kitchen in a house of change. they are still on the road w the party#not to say i think that maybe chillin out in one location with some loved ones and planned visits from their friends would fix siffrin#but i am saying that they do seem to hoard random items at every given oppertunity. which is an interesting habit#isat#isat fanart#in stars and time#in stars and time fanart#isat spoilers#sifloop#isat siffrin#isat loop#sloops#lucabyteart#but yeah no i dont actually know that siffrin would wwwant to be . travelling literally forever. given the. well. um#that one QnA answer especially. the immediate deflective joking when asked how long they'd been a traveller. mm.#it's not like they chose this life is the thing. and we know they have a habit of forcing themselves to 'stick to the script'#i really do think they'd be better for some stability. its not like you cant have a house and also go on fun travel holidays also#(if you want my real opinion. why not just move to bambouche to help raise bonnie. but. that's fanfic territory at that point)

714 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Clone Force 99 died with Tech"

which means

Crosshair doesn't think Clone Force 99 died when he left

He knows they went on without him

For a long time

#having thoughts and feelings#the bad batch#the bad batch spoilers#tbb spoilers#clone force 99#plan 99#tbb tech#tbb crosshair

538 notes

·

View notes

Text

Robin¹ aka Nightwing had Batgirl... (the ginger one), then Robin³ had his own (The blond), and then the blond Batgirl (he's pretty sure she was a Robin too?) became spoiler–

The dark shadows, Danny swears, that was a Batgirl too, she goes by BlackBat now tho, had a major upgrade and everything!

But, Danny nods, the current Robin doesn't have a Bat partner.

And he did say he wouldn't be Phanton anymore. No hero (or at least solo) and...

Would Sam really be mad if he got himself the Bat title and kicked ass with Robin?

(It would be fair, Robin saved Cujo's life. That's the rule of ghosts, give back what was given. He saved Cujo's afterlife, so Danny as Cujo's behalf will make sure Robin does not die.)

#danny has a PLAN#he will force his way into barbaras heart in a smart way and get that OUTFIT#he will become Batboy (thats such a stupid name hed rather stick to phantom but new city new name)#he could also just?? he batgirl and change his physical appearance#dcxdp#dpxdc#dp x dc crossover#fic prompt#writing prompt#dc x dp prompt#dc x dp#dp x dc#dp x dc prompt#DAMIAN HAS NO CLUE WHATS COMING FOR HIM

784 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 1: Holy | Meteor

Two shooting stars return home, together this time.

#kingdom hearts#soriku#sora x riku#sorikuweek2023#kh2#i plan on letting these just be messy but i ended up kinda coloring it wow!!#more important to finish the piece than anything and i'm letting this force me to complete things#anyway shoutout to cuccochu for setting me on the right path

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

(part 1 here) (part 2 here)

Gareth, in a feat of truly impressive self-restraint, lasted all the way through their band practise before asking.

The four of them packed into Eddie’s van. Gareth had ultimate dibs on the front seat since he’d known Eddie the longest, despite being in different grades.

“So,” he said, breaking the expectant silence. “Steve Harrington?”

Eddie groaned and let his head thunk against the steering wheel, not even flinching when the horn sounded. “Please don’t.”

“Nah, man. It’s all good,” Jeff soothed as he leaned through the gap between the front seats. “We’ve not got a problem with it, but Harrington? Really? Not exactly your type.”

Eddie laughed humourlessly. “You don’t even know the half of it.”

Gareth turned in his seat to share a loaded look with the two sat in the back as Eddie started the van. They were planning to find out the all of it.

“And you guys just don’t have a problem with it?” Eddie asked once they were well on the road to Loch Nora. “I know you don’t exactly have the best memories of him from school.”

Eddie tapped his fingers against the steering wheel in a rhythm that didn’t even match the tape that was playing quietly. He was nervous and Eddie hated being anything other than completely sure of himself.

“You’re right, we don’t have the best memories of him, but the guy saved your life, Eddie,” Gareth reminded him gently.

It was the worst phone call he’d ever received in his life. He couldn’t imagine getting another one like it. Wayne on the other end, breathing shakily as he told Gareth that Eddie was in the hospital, that he wasn’t waking up but that he was going to be okay and that he thought Eddie would really like it if his best friends, his brothers, were there when he woke up.

It had been hard seeing Eddie like that, small, frail and paler than usual, no rings or battle vest, no Eddie. Steve and Wayne had been sat at his bedside, both just staring into the middle distance, when they had filtered into the room. Gareth remembered so vividly the sinking feeling that he felt at the quiet. Eddie hated the quiet, he was never quiet.

And maybe it had been the wrong thing to do, to interrupt Steve and Wayne in such a way, but Gareth knew Eddie. Wayne, for all he tried, never really understood his nephew and Steve was clearly a new development.

So he started talking. He talked about school, about the assignment he was working on, and he talked about the girl that worked behind the counter of Camelot, and he talked about his mom chewing him out for almost crashing her car. Jeff and Grant, who knew exactly what he was doing, picked up the thread when it sounded like he was running out of steam.

He just couldn’t stand to let Eddie exist like that.

Gareth owed him that much. Gareth owed him everything.

Eddie who had stood on lunch tables and made himself the centre of attention, the target, when Gareth couldn’t fight off the tears after getting an F on his history midterm. Eddie who got them their first paying gig as Corroded Coffin and pushed them all to take their music seriously.

He joked about them being his sheep, but he wasn’t exactly wrong.

“Yeah, man,” Grant doubled down. “We can’t hate him anymore. Without him you wouldn’t be here. And you trust him?”

“With my life,” Eddie confirmed with conviction.

“Then that’s good enough for us. It’s all water under the bridge,” Jeff concluded. “Now turn that fucking music up, I don’t want to cry in the back of your shitty van, Ed.”

Eddie cracked the music up with a blubbery laugh and all four of them yelled along with Ozzy for the rest of the drive.

The door to the Harrington house was opened before they even got out of the car. Steve stood there, excitement buzzing around him.

"Ed," Gareth stopped him with a hand on his arm before Eddie could scamper off. "Do they know about you?"

Eddie shook his head. "Only Buckley."

Gareth nodded once and jumped out of the van. He was still too short to climb out normally, and at seventeen, he didn't have much hope for a late growth spurt to help him out with it.

“You been waiting for us all this time, Stevie?” Eddie teased as he slammed his door shut.

Steve laughed, stepping out the door with bare feet on the porch so he could accept Eddie’s hug. He didn’t have a shirt on, pink scars on full display, and short yellow swim shorts on. It was nothing short of a miracle that Eddie still had the brain cells to flirt.

“We could hear you guys coming all the way up the street.” He explained as Eddie let go of him. “Ozzy?”

“Oh for fuck sake,” Jeff muttered from his place at Gareth’s shoulder. “How is Ed not seeing this?”

“He had to do senior year three times, dude.” Grant fired back from Gareth’s other side, but still not loud enough for Eddie or Steve to hear. “Steve could plant one on him right now and he’d still find a way to make it a just friends thing.”

Steve, having finally managed to pull his focus away from Eddie long enough to see his other guests, waved them over. “Come on in guys.”

Gareth made sure to share with Steve what he hoped past for a friendly, macho and athletic half handshake as he passed him to go through the door.

“Thanks again for having us. You really didn’t have to invite us,” Grant said, using the good manners his father taught him.

Steve clapped him on the shoulder. “No way, man. I’ve been trying to get Teddy to bring you guys over for ages. He talks about you all the time.”

“You talk about us, Ed?” Gareth asked with a shit eating grin.

Eddie pushed at his shoulder, sending Gareth stumbling towards the open french doors. “Yeah and I’ll talk about Tammy Thompson if you don’t shut up.”

Jeff and Gareth snickered together. They knew all about Gareth’s benadryl induced dream about Tammy Thompson because when he told them he was still half high on the same benadryl.

Gareth huffed but didn’t say anything. He didn’t doubt that Eddie would follow through with his threat if pushed.

Out in the garden, it seemed that the party was already in full swing. There were scattered cans, Robin and Nancy were giggling together at something, and s portable stereo playing The Cure.

Steve smiled shyly. “We got started without you.”

His voice seemed to draw the attention of the other four people. They all stopped in the middle of their conversations.

“Whoa, dude,” The guy with long hair that Gareth didn’t recognise said to break the silence. “Your cult looks super culty.”

Gareth froze. Jeff and Grant did too.

But Eddie, determined to always surprise them, just laughed. “Not a cult, my man.” He kicked his shoes off by the door (surprising how little care he paid them since he sulked for a week straight when Jeff accidentally scuffed them) and started making his way over to the sun loungers. “This the legendary Corroded Coffin. Gareth, Jeff and Grant.”

He pointed them out each in turn then shucked off his shirt and started working the intricate handcuff clasp of his belt.

Gareth pretended he didn’t hear the strangled noise that came from Steve’s throat.

“And guys, this is Argyle. You know everyone else.”

Gareth waved politely but awkwardly and it was returned by a chorus of ‘hello’s.

Once Eddie had divested himself of his jeans, the black swim shorts he had forced underneath them sitting starkly against his pale skin, he dipped back in his jeans pocket to pull out two perfectly rolled joints.

“I brought party favours!” He waved them in front of Argyle’s face how he would sometimes play with the stray cats that skulked around Forest Hills.

Grant groaned. “Eddie, you know I can’t afford weed right now.”

Eddie scoffed at him. “These’s ones are on the house, Ad-Grant-age. This is a party after all.”

Steve, somehow having forced himself out of the trace that Eddie’s torso had put him in, was the first to start moving. “You guys can change inside if you want. There’s bedrooms upstairs or the bathroom just past the kitchen. I’ll get some more drinks. Can we switch this tape?”

The rambling did nothing to hide the redness of his cheeks. If anything it just brought more attention to them.

“Your tapes are shit, Steveo,” Robin informed him happily. “But this one is also awful, so yes I will change it just for you.” She ignored Jonathan’s annoyed hey and beckoned Steve to follow her.

Eddie settled on the sun lounger next to Argyle, already having pulled a lighter from somewhere.

Gareth took that as his cue to drag Jeff and Grant inside to change.

Jeff, as soon as they were out of hearing range, asked, “When has Eddie ever given us free weed?”

Gareth shook his head. “I’ve known about this crush for less than a week and I’m already tired of it. We have to do something to get them together.”

Grant narrowed his eyes. “You already have a plan, don’t you?”

He pushed them both towards the bathroom. “Get changed, our work starts today.”

(part 4)

#steddie#eddie munson#gareth emerson#steve harrington#corroded coffin#bit of a longer one but Gareth was having feelings and i needed to let him have his feelings#pool party/ operation get steve and eddie together planning party next part#again if you asked to be tagged; i don't do that because it makes me anxious and i wouldn't write anything#so figured it was better to write the stuff and not tag people than force myself into anxiety and never post anything again :)#my fic

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

“What Should It Look Like?” Part III: The Navy (OLD ESSAY)

This essay was originally posted on April 20th, 2022, and is a continuation of the "What Should It Look Like?" series of essays.

In this entry in the series, I go after the Navy - which I think in an Armed Forces of shitshows, is by far the biggest shitshow currently. However, in modern warfare, a navy is still crucially important, so I try to wrap my head around how to make it suck less in service of a foreign policy that also sucks less.

(Full essay below the cut).

Thought I forgot about this series, didn’t you?

Well, I didn’t forget about it. But in case you hadn’t noticed, global events over the past few months had distracted me some. While the war in Ukraine is by no means over and we should still pay close attention to it, I think I at least have sufficient breathing room right now to write about something else for a bit (I don’t want to become a single-issue commentator anyway). So, now seems as good a time as any to return to imagining how I would restructure the U.S. military in a hypothetical future where it was being used to more appropriate ends (if you’re new to this, I’d suggest starting back at part one and working your way up to this).

We’ve already talked about everyone’s favorite green machine, the U.S. Army. Now it’s time to take to the waves and try to unfuck what is currently the most fucked of all the services: the U.S. Navy. Oh, don’t get me wrong: all branches of the military are fucked up, but to put an Orwellian spin on it: some are more fucked up than others (and the some in this case is the Navy). So, anchors aweigh and full speed ahead: let’s kick this pig.

The U.S. Navy: America’s Floating Disaster Factory

Oh, U.S. Navy. You’re such a glorious trainwreck of an armed service. Whether you’re driving your ships into other ships, getting embroiled in massive and now infamous corruption scandals, or engineering procurement boondoggles that would make all the other services blush by comparison, you really are leading the pack when it comes to being the problem child of the Armed Forces. Add in the fact that out of all the services, you’re the one that’s gone the longest (since the Battle of Leyte Gulf in 1944) without actually fighting anyone who can give you a run for your money, and you’re just a recipe for disaster (beyond the minor ones you cause just by existing).

While it may seem tempting to throw the baby out with the bathwater, in a world where wars do unfortunately need to be fought and your military needs to move vast distances in order to fight them, a Navy is essential. In the event of a large scale war, the vast majority of the military’s heavy equipment and supplies will have to be moved by ship – as does the vast majority of the world’s trade in general. While air travel may be good for rapid deploying light forces and some equipment, moving an entire force by air is highly inefficient in terms of time, energy, efficiency, and more. As long as you’re going to need to move most of your forces and supplies by sea, and most of what keeps the world running moves by sea, you’ll need forces to control the sea and do battle on and from it as needed.

With that requirement laid out pretty clearly, how do you solve a problem like the U.S. Navy? I’ll give you a bottom-line up front on that now: cutting back in some areas and doubling down on others in terms of types of ships, and adopting a completely different strategic mindset.

The Carrier is Dead; Long Live the Carrier

I’m going to tell you right now: if you’re a big fan of aircraft carriers and carrier aviation, you’re probably not going to like what I have to say next.

However, I will give anyone of that disposition some small reassurance now: I don’t think aircraft carriers are obsolete, per say. I think they still have a use case. However, I think that use case has become – and will continue to become – far more limited as new capabilities and concepts in warfare are developed (and I’ll get more into why I think that in a few paragraphs).

The aircraft carrier was a game changer when it first saw combat in World War II, after having been developed between the two World Wars. It quickly rendered the battleship – the previous capital ship of naval warfare – all but obsolete and has dominated the high seas ever since. But now, crucial developments in military technology threaten to knock the carrier off its throne.

This is not to say that carriers have always been invincible. A quick peek at all the carriers lost in combat by all participants in World War II will show you that was never the case and that the carrier has always had threats. But those threats have evolved significantly to a point where the push and pull of advantage between the carrier and its counters is shifting in the latter’s favor.

The biggest threat to the carrier – and warships in general today – are anti-ship missiles (AShMs). These aren’t exactly new and have been a threat for a long time, but to be a true threat meant getting a platform carrying them – be it a ship, an aircraft, or a land-based launcher – close enough to fire and then getting the missile past all the carrier’s defenses (such as the AEGIS Combat System or Close-In Weapons Systems gatling guns). But missiles have increased dramatically in sophistication in recent years, extending their range and their precision. When you compare the range of the U.S. Navy’s standard anti-ship missile for the past forty years – the Harpoon – to the YJ-18 of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army Navy, the Harpoon is rapidly becoming outclassed (which is part of why the Navy has been working feverishly to deploy an anti-ship variant of the longer-ranged Tomahawk cruise missile to the fleet in recent years). There’s also the unfortunate fact that, whatever defenses you have – or are building – they could always be saturated by more missiles.

But extended range models of standard anti-ship missiles and anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCMs) aren’t the only worry on the high seas. Now you also have to contend with a burgeoning new class of anti-ship missile: the anti-ship ballistic missile – like China’s DF-21D with a potential range of over 1300 miles. While ASCMs like the YJ-18 and Maritime Strike Tomahawk already have generous ranges, a ASBM puts an ASCM to shame with its range. An adversary with ASBMs on mobile launchers could position them all along its coastline – or even further inland depending on how extensive its range is – and fire on targets thousands of miles out at sea. And if you deployed an ASBM onboard a surface ship or submarine – as China reportedly may be planning on? Then you’d have even fewer places to hide that were out of range.

Obviously, these weapons aren’t infallible or invincible – no weapon is. Even if you have a fancy missile with a long range, you still need to find and fix your target before you can engage it, and the oceans are vast. But technology is improving on that front as well, especially when it comes to space-based sensors. What this all adds up to is a much harder time for large surface fleets in a major war at sea. While war on the ocean’s surface isn’t going anywhere, its certainly undergoing a rethink.

The carrier requires the biggest rethink in light of these changes, seeing that for any nation that possesses them (like the United States which possesses eleven – more than any other carrier possessing country), is going to be the largest and most conspicuous target on the water. If you do lose one, you stand to lose – in the case of a Nimitz-class – upwards of over 5000 officers and crew and as many as ninety aircraft and helicopters on top of the nearly 10 billion USD carrier itself. While the carrier will still have defenses both on board and in its accompanying battle group, as mentioned before those defenses are less certain in the face of technological developments and also potentially with sheer numbers. An AEGIS missile-defense system may be good, but if you keep firing enough relatively cheap anti-ship missiles at a group of ships, sooner or later one will get through (or the defender will just potentially run out of ammo first).

Again, carriers aren’t completely obsolete. Having a mobile platform capable of launching and retrieving both fixed-wing and rotary-wing aircraft at sea is still useful. Not every potential adversary in the future will have the advanced anti-ship capabilities that some of the most sophisticated militaries in the world are developing or even marketing. There’s still a number of countries around the world that see value in having carriers – including China, which has a third on the way with a fourth possibly in the works. However, maybe like how most other countries in the world that have carriers only have one, two, or at most a handful, we don’t need ten or twelve. It’s an asset that is useful in some situations, but not in all situations. I can’t say for sure how many carriers we should have, but I can say we definitely don’t need as many as we have now and that the final number should ultimately be based on the scenarios we see as most likely and the carrier’s actual role in them.

The few carriers that you’ll hang onto don’t have to be as big as a massive Nimitz or Ford-class “supercarrier” either. Take for example the French Charles de Gaulle-class nuclear-powered aircraft carrier – the only other currently operational conventional “flattop” carrier not in U.S. Navy service. Though at full load it is less than half the tonnage of a Nimitz class carrier, it still carries an air wing of up to 40 aircraft, including multirole fighters, support helicopters, airborne early warning and control aircraft, and more. It does all this with less than half the compliment of a Nimitz class. In a much-reduced role for carriers for the U.S. Navy, several of this size would still go a long way. And this is before we even go down the rabbit hole of STOBAR and STOL carriers – which most other countries have, but I just don’t have time to get into right now. Basically, you got proven options to go smaller and fewer with.

The bottom line for carriers is that they are not obsolete, but their application will become more limited and focused. One way or another, they’re going to have to operate in more permissive environments – either in warzones where extensive anti-ship threats are less pervasive, or in warzones where the anti-ship threat from all domains has been degraded enough to allow them to come in and support the forces that are already doing battle. Carriers still have a use, but more and bigger is not the way forward. The way forward is fewer, smaller, and more smartly used.

“Haha Missile Go ‘Woosh’”

The Navy doesn’t appear to be blind to the changing landscape in maritime warfare, which is why it’s been pushing its concept of Distributed Maritime Operations (DMO). As with most military concepts, a lot of it is pedantic and inscrutable, but the basic idea of DMO is to spread ships out further rather than concentrating them in easier to find and target groups – keeping them connected and coordinated as they do so. The idea is to create targeting problems for an enemy with a large – but not infinite – number of long-range missiles of various types; to make it harder to find and fix targets and make it more difficult for them to choose where to utilize finite resources and munitions.

This is a good first step, but the Navy is doing this while still clinging to the concept of the carrier as it continues to forge ahead with the new Ford-class to replace the Nimitz (which is just as large and has been rife with problems throughout development as all recent Navy ships have been). Meanwhile, the Navy continues to debate with itself and Congress just how many ships it should have (or how many it can really afford instead of giving us all health care and forgiving my student loans – FORGIVE MY FUCKING STUDENT LOANS, JOE).

This brings us to the second half of why fewer and smaller carriers are better – aside from them just becoming more vulnerable targets that offer an adversary a lot of gain from their destruction while offering their operator less and less utility. By having fewer and smaller carriers, you free up a vast amount of resources to put into areas where you get more bang for your naval buck (or send some of that money back to us peasants to build roads, schools, hospitals, etc. but what do I know I’m just a dumb socialist).

Basically, if modern naval warfare is a glorified missile duel, you’re going to want more missile slingers, and right now carriers are taking up resources that could not only be freed up for missile-launching ships but would get more value per ship if you chose to focus on that. You could buy a larger number of smaller ships like frigates and destroyers that present a harder to find target but still have considerable firepower. This applies not just to surface ships, but also missile submarines that could fire land-attack missiles and AShMs as well as torpedoes, and are even more difficult to find in the open ocean (I could go on a whole thing here about anti-submarine warfare but just rest assured that even under the best of conditions ASW is extremely difficult to do; oh, and seeing how ASW is hard to do, maybe if carriers weren’t sucking up so much manpower and resources you could focus on more ASW ships and aircraft)

The aircraft are another part of the equation on why cutting back on carriers gets you more, because not only do you no longer have to worry about the carrier but then also about supporting the numerous aircraft that it carries with munitions, fuel, maintenance, etc. Again, that’s resources you can divert elsewhere for more effectiveness (or again, back to actually trying to improve civil society somewhat). If your carrier is so vulnerable that moving close enough to an operational area to deploy its aircraft poses too much of a risk to the carrier, then maybe you’re better off hitting whatever you would have hit with aircraft with missiles delivered by ship, land-based launchers, or long-range bombers and other aircraft that can carry missiles to a stand-off distance and then fire them and turn right back around. Maybe the aircrews and maintenance crews might be better used in another capacity rather than sailing around on an airstrip that is only useful if it risks making itself a gigantic target.

Also, while I’m always the guy who cautions people not to make Skynet real, this is an area where unmanned vehicles could play a critical role. While I’m very much against making drones that can think and operate on their own, I think a more sensible road forward in this area for all domains is “manned-machine teaming,” where you have several unmanned vehicles that respond to the orders of a human or humans in a manned system and share information between the systems. In this case, instead of having a surface action group of three manned warships, you could have one where there’s one manned warship acting as the command ship, with a handful of unmanned ships essentially acting as floating, self-propelled missile launchers. Not only does not having to have crew on board those ships help you cut back on numerous costs and feel the potential loss of a ship less, but you could also send an unmanned ship into areas that would be more of a risk for a ship with personnel on board. I’m never in favor of creating weapons that operate without any human control, but this is an area where they can act as a force multiplier.

Putting An End to “Everywhere and Nowhere”

I don’t want anyone to be under the illusion that if you just got rid of most of the Navy’s carriers and bought a bunch of ships that just fired missiles that everything would be peachy keen with the service. While that would go a long way in pushing the Navy towards what it ought to be, it is only one part of the equation. There are obviously many other issues that the Navy – as the military as a whole – struggles with. I can’t go into all of them here, but I can go into one big issue that has led the Navy to where it is today and that’s it’s the idea at the core of how it currently operates: the obsession with presence.

At the end of the Cold War with the “peace dividend” that was bought and the cutbacks and drawdowns that ensued, the Navy was faced with a difficult choice with how it would structure itself and operate going forward in the post-Cold War world. For a myriad of reasons, the choice that it ultimately made was to prioritize a global presence above all else, rather than an actual ability to fight a war at sea. Former Deputy Secretary of Defense Bob Work lays this out in a piece for the U.S. Naval Institute (and while he immediately loses credibility in my book for referencing Samuel Huntington, he does make some good points). In a more ideologically aware reading of Work’s analysis, presence was seen as critical to demonstrating the Navy’s worth in a post-Cold War world without a major adversary, preserving American influence around the world by constantly being a reminder of American military might, and also potentially even deterring wars from breaking out through the constant presence of substantial military power.

Obviously, this did not work out. Countless wars have broken out since the end of the Cold War (some of them by our own doing) that were not deterred by constant U.S. Navy presence. Likewise, the degree to which the United States holds influence over the world compared to its fleeting moment of hyperpower in the 1990s is debatable. All the Navy has to show for it in return is a service pushed to the limit. A service that, despite being among the largest and best equipped navies in the world, many times seems to be everywhere and nowhere at the same time, jumping back and forth between places like a 90s sitcom character trying to be with two dates at the same restaurant. A service that, despite having several hundred thousand personnel, runs them ragged to the point they’re crashing ships into one another out of exhaustion and poor training. The U.S. Navy may not be to the point of the Russian Navy (yet), but on a long enough timeline without serious change it’s not hard to imagine it getting there.

One of my oft returned to concepts is the idea that empire is actually toxic to a military. Maintaining empire by necessity requires putting pressure and stress on a military that continuously erodes its effectiveness, professional culture, morale, equipment, and more. You see this in the case of the Navy’s focus on presence in the post-Cold War era, scattering its ships to the four corners of the globe, often with a mission no more specific than “to be there.” Now, even as it’s faced with a potentially serious challenger in the form of the ever-growing Chinese PLAN, the Navy still has this presence mindset that hinders it from returning to that original purpose of fighting a war at and from the sea. It just further reinforces that not having an imperial mindset and approach to the rest of the world is not only betters for the soul ideologically, but also sound military sense if you want a more healthy and capable force.

If you’re not constantly focused on having a ship in every single potential crisis zone or place you have an interest throughout the world, when the shit hits the fan and a crisis becomes serious enough to risk escalating into a war, you may actually have ships available with crews that might actually be well rested and know how to do their jobs that can respond to that crisis and be ready to fight. If you’re not focused on presence for the sake of influence, when an ally or partner comes under attack by an aggressor and requests help, you’ll actually have a naval force that is in good enough shape to assist them. Maybe its overly simplistic to me as someone who’s never served in uniform or taken a class at the Naval War College, but maybe also its just hard to wrap your head around these ideas when you’ve been drinking the Kool-Aid your entire career.

As much as I’m sure many on the Naval staff would love a return to the 600 ship Navy of the Cold War, that’s never going to happen even with the most generous of defense budgets under the current system – let alone under the system we’d rather have in place. Accepting that, then the Navy needs to step back from the obsession of being everywhere at once if it wants to be in one or two places when its really needed and then be able to actually engage in combat to a useful end. It needs to accept that it cannot on its own act as a deterrent and that at the end of the day its role is to fight a war when it is called upon to do so.

Semper Fortis (but for real this time)

A navy will remain a crucial component of the military even under a democratic socialist system, if we want to carry out the strategy I outlined in part one and actually military exercise solidarity with other peoples around the globe. A navy is necessary not only to keep hostile forces from the controlling the seas, but to support forces operating on land and in the air. An effective navy carrying out our strategy not only needs to divest of less useful systems and invest in more practical, efficient, and effective ones, but needs to completely reconceptualize what its purpose is. It needs to not only refocus on fighting a war at sea, but rethink the entire reason its fighting a war at sea to begin with. It needs to understand it is doing so not for the sake of its own influence or the influence of a particular country or flag, but to do so in order to play its part in protecting others that are in danger when war erupts. To ensure that the supplies necessary not only to fighting war but maintaining peace and life are able to flow freely.

For centuries, Navies have been seen by empires as critical to guarding the lifelines of capital and imperial power. For ensuring that an unbroken connection was maintained between the imperial core and its various markets and dependencies. That perception must be broken and replaced with a different concept of lifelines. That the Navy is instead responsible for guarding the lifelines that link together working peoples that are dedicated to building freer and more just societies for all who live in them. Lifelines that allow peoples and nations that are working to create a better world for themselves and others to defend one another from forces of reaction and authoritarianism. In this hypothetical better world that I imagine to keep myself from going batshit crazy, navies must play the role of helping to keep empire and fascism at bay, not working as an active agent to facilitate their spread. As with our perception of war in general as leftists, we have to flip the narrative on the Navy. We have to make sure that when warships put to sea, they’re doing so to defend others, not to facilitate their oppression.

Ok, alright, I’m dipping into the purple prose a bit too much now so I think it’s time to wrap this one up as I’m already over 4000 words (constantly setting new personal “bests” with these). In our next installment in this series, we’ll be looking at the Navy’s own private Army – the United States Marine Corps, and hoo boy I hope you’re not too attached to them because I have plans (don’t worry Marines, the plans I have for you are much like my plans for carriers; you’ll still be around, there’ll just be much, MUCH fewer of you). Also, if you thought I forget about amphibious assault ships in my rant on carriers – that’s where I’m gonna cover them. For now, though, anchors aweigh on my end. Until next time, stay safe out there, folks.

#essay#War Takes#War Takes Essay#leftism#leftist#socialism#democratic socialism#international relations#IR#national security#national defense#international security#foreign policy#foreign affairs#military intervention#defense policy#force planning#force development#force structure#US Navy#U.S. navy#United States Navy#war

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

he makes this joke every time.

#sissel#yomiel#ghost trick#ghost trick phantom detective#ghost trick spoilers#art#my art#fanart#comic#halloween 2023#bad horrible pun this joke has to have been done to death already#you wouldn't believe how long it took me do to the ghost world on god#all done in the mac equivalent of ms paint btw. yes those transparent people were painstakingly drawn by hand.#sissel thinks he's hilarious but it's not like anyone can see his jokes. his talent is being WASTED.#there's a reason sissel is purple yes.#the kids go “nice costume” to yomiel every time. he's not wearing a costume.#depending on when you think this takes place it's absolutely hilarious#pre-canon? dead man answering the door (interrupted from plans of revenge) and getting his fashion sense annihilated by preschoolers.#post-canon? catsitter forced by wife to go answer the door and getting verbally destroyed by kids because she knew it'd be funny#deserve#no watermark or signature because i forgot again. and because it'd look out of place#the big brain play is to make a joke so bad they won't wanna steal and reupload your stuff anywhere#took off the halloween tag bc there are GT spoilers

895 notes

·

View notes

Text

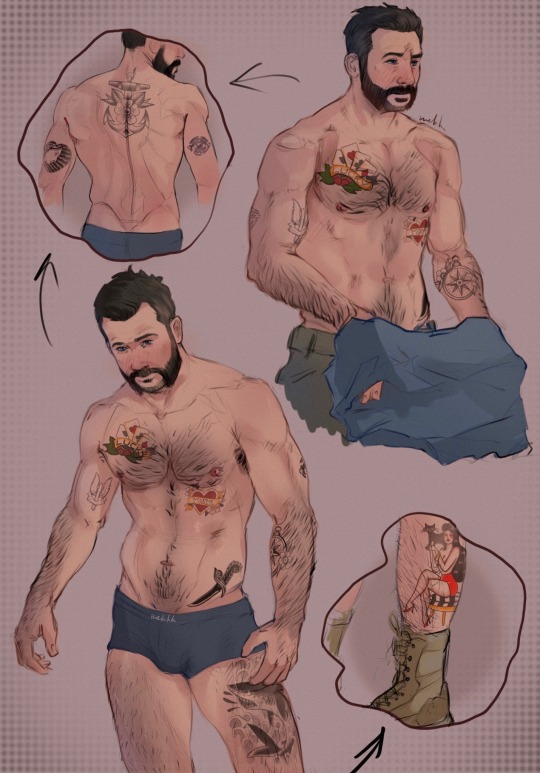

Captain Price with tattoos ✍️

#can’t believe hes finally dooooneee#also I didn’t plan to draw him in underwear#he waw wearing jeans in the beginning#but then i realized#that he MUST have a thight tattoo#so I had to undress him#captain price#captain john price#call of duty modern warfare 2#call of duty#john price#call of duty modern warfare#john price x reader#task force 141#call of duty mw2#barry sloane#barry#love him#modern warfare#call of duty fanart#captain price fanart

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

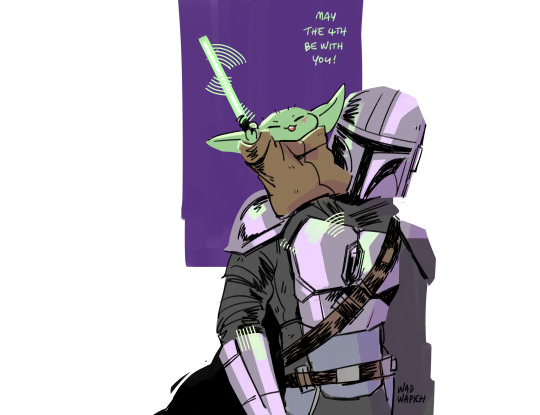

Happy Star Wars Day!

#may the 4th be with you#star wars day#grogu#the mandalorian#din djarin#din and grogu#clan of two#star wars fanart#may the force be with you all!#i never draw something this fast hjdksjh#i was't planning to draw for sw day at first tbh#cuz uni's seriously killing me rn lmao#i forgot to draw the signet pls forgive me

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

cw forced intoxication / dubcon / somno

Nobody touch me I'm thinking about the 141 holding you down and taking turns with you, and while Ghost is splitting you in half on his cock, Soap is grabbing you by the chin and spitting liquor in your mouth <33 Or Gaz holding your head still by the hair as Price fingers your ass open, Gaz cooing at you as he holds the bottle to your lips. You want so bad to be good for them, be the cool fun sexy girl so you gulp down the firey drink like you never have before. Even as your dizzy brain gives out and you fall asleep, the men are happily sober and starting round three on you.

#noel.txt#141 x reader#cw dubcon#i say dub bc i imagine reader planning this out beforehand but yknow#cw forced intoxication#cw somno#i sat on this concept for a minute bc despite my love of it it squicks me out so i might not write more/answer asks abt it lol#brain is weird

776 notes

·

View notes