#enlil-bani

Text

my favourite manner of royal succession (aside from the obvious choice, abolition ofc – be it voluntary or guillotinous) is substitution-made-permanent

which we have one record of, from the 19th century BCE (about a century before the infamous Ea-naṣir and his subpar copper), when a king of the Isin dynasty that appears towards the end of the Sumerian King List, Erra-imittī, was succeeded by Enlil-bāni, a gardener that he crowned himself

this comes from my favourite ritual from the ancient world, the ritual of the substitute king. you see, when an omen predicted that the king was in danger, a servant would be chosen to take his place – the substitute would be given the crown, dressed in royal attire, live in the palace and be treated as king for the duration of the danger not only by the (other) servants/subjects, but hopefully (crucially!) also by the gods. after the danger passed, the real king returned and if the gods hadn't taken care of him already, the substitute was ritually slaughtered

Erra-imittī is notable because once he placed the crown on the substitute, Enlil-bāni, a gardener from the royal palace, he went on to choke on some hot porridge and dropped dead. clearly, the gods saw through Erra-imittī's ruse. by way of this "gastronomic mishap" Enlil-bāni simply did not return the crown and continued to rule for another 24 years

*because of some inconsistencies in the different versions of the SKL in this part, it is also possible that this is a secondary explanation for the break in dynastic succession, invented later to legitimize an usurper's taking of the throne. but even if this is the case, the fact remains that this was then apparently a conceivable, plausible scenario

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

https://qgpennyworth.com/portfolio/story-of-the-ancient-world/

Story of the Ancient World is a work from Holy Nonsense, a Creative Commons project. View Holy Nonsense 2020 here.

Each entry (single page or multiple pages of the same work) is released under an individual CC: Attribution, Non Commercial, No Derivatives license. That means you can repost this work as-is anywhere for any non-commercial purposes.

Image descriptions, including transcriptions of text, are expressly allowed, but just make sure you include the credits that are baked into the image when you do them. Image Description after the cut.

A STORY OF THE ANCIENT WORLD

It was a custom in ancient Babylonia to choose a “king for the day” one day out of each year, taken from the common stock. This king would rule Babylon until his first sunset on the throne, after which he would be sacrificially put to death.

There is one incident in which the real king, Era-Imitti, chose his gardener, Enlil Bani, to be this doomed king. Era-Imitti, ironically, was even more doomed, and died of natural causes while the ceremonial party raged on. The Mock King ruled for two decades, and did it well.

Thus may the sacrificial lamb wield the dagger for himself. Somebody, somewhere, has to win the lottery.

Marginalia: A woman with entirely too many breasts is flanked by overflowing cornucopias, and has some kind of crown on her head. Text beside her reads ““My short term goal is for all of Canada to suck my balls.”

#Holy Nonsense#hail eris#all hail discordia#fnord#apocrypha discordia#novus ordo discordia#discordianism

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

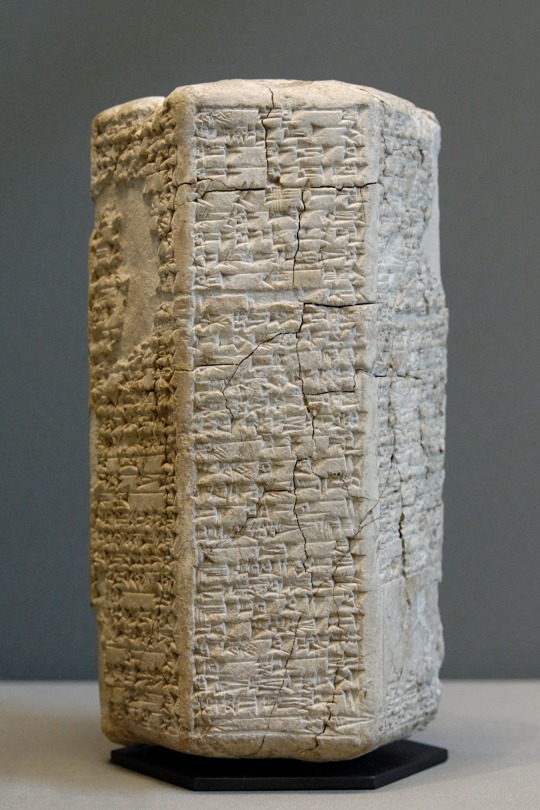

Hymn to Iddin-Dagan of Isin (c. 1950 BC).

During the dynasties of Isin and Larsa, hymns exalting the king were common. This text is written in Sumerian, and is probably a school document.

“To Iddin-Dagan, [the god] Anu decreed a great fate...to the pastorate of the country he raised him, [the god] Enlil looked at him favourably...O Iddin-Dagan, who is like you?”

The Isin-Larsa period (c. 2025 – 1763 BC) followed the Ur III Period, which had ended with the Elamite invasion of 2004 BC. During this time, life was unstable, and non-Sumerian invasions were common. The dynasties of Isin and Larsa were vying for dominance, with Larsa eventually winning out.

During the reign of Ibbi-Sin (the last king of the Ur III Period), the governmental official Ishbi-Erra moved from Ur to Isin and established himself there as a ruler, beginning the Dynasty of Isin. He defeated Ibbi-Sin in battle, and although he wasn't able to expel the Elamite invaders, he did manage to drive them out from the Ur region. The Dynasty of Isin thus had control over Ur, Uruk and Nippur (cities of cultural significance) and flourished for over 100 years.

But Gungunum of Larsa (c. 1932 – 1906 BC) captured Ur during his reign, and Isin lost an important city and trade route. The next two kings of Larsa cut Isin completely off from canals, and so Isin declined rapidly. The usurper Enlil-bani seized power in c. 1860 BC, and Isin lost Nippur at some point as well. The Dynasty of Larsa eclipsed Isin in power and control of the region.

#history#military history#politics#economics#trade#languages#isin-larsa period#dynasty of isin#dynasty of larsa#mesopotamia#sumer#isin#larsa#ur#uruk#nippur#iraq#al-qādisiyah governorate#iddin-dagan#ibbi-sin#ishbi-erra#gungunum#enlil-bani#sumerian language#cuneiform#sumerian cuneiform

61 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Image: Detail of an alabaster bas-relief depicting the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal. Mesopotamia, Iraq. Circa 645-635 BCE. The British Museum, London. Photo by Osama S.M. Amin.

“One of the strangest and most elaborate rituals practised in ancient Mesopotamia, and one that occasionally went terribly wrong: the ritual of “The Substitute King”.

The people who inhabited the Mesopotamian basin in ancient times, the Sumerians, Assyrians & Babylonians among them, were what today we would call very superstitious.

If you were an ancient peasant relying on the floods to inundate your fields every year, you would see start to see the river as a conscious entity that could be either happy or angry. And you would want to keep it happy.

Kings in ancient Mesopotamia were considered to be where the powers of the gods intersected with mortal men.

The most significant way that the Gods were thought to communicate with man was through the sky.

Of all the symbols seen in the sky, the gravest of them all was the eclipse. That’s because certain solar and lunar eclipses were thought to signal the coming death of the king.

Luckily, some ancient innovator thought up a solution to this problem. If death was coming for the king… what if someone else becomes the king for a little while? Thus was born the ritual of the substitute, or šar pûhi (shar PU-khee) in Akkadian.

According to the ritual, the chief exorcist chose a common man. Various cases saw prisoners, condemned men, POWs or men deemed to be "simple" selected. The chosen man was then dressed in the king's robe & crowned. He would carry out all the rituals associated with the kingship.

Meanwhile, the real king went into hiding under heavy protection. In order to hide more effectively from the oncoming misfortune, some kings even changed their names. One especially cautious king even went as far as changing his title to "ikkaru", “the farmer”.

Everything was carefully managed. The real king received regular updates while the substitute went about his business & even married a queen. This went on for an allotted period (in one case as long as 100 days). Once that time was up, the poor substitute was put to death.

When the substitute was put to death, great effort was made to ensure that the curse didn’t linger. He was buried in a tomb and mourned as though royalty. Rituals were performed, and his royal throne, table, weapon, and sceptre were all burned.

There is evidence that on at least one occasion, a substitution didn’t go quite as planned. One king of Isin, Erra-Imitti, enthroned his gardener during the ritual. He then died soon after, leaving the commoner as king. Presumably having consolidated some power, the gardener was allowed to stay, & ruled for 24yrs as king Enlil-bani, according to the Ur-Isin kinglist.

Practice of the ritual seems to have gone on into the time of Alexander’s conquest of Babylon, and into Achaemenid Iran.”

(source: @PaulMMCooper )

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

How eclipses were regarded as omens in the ancient world

http://bit.ly/2vMTkLm

A solar eclipse observed over Grand Canyon National Park in May 2012. Grand Canyon National Park

On Monday, August 21, people living in the continental United States will be able to see a total solar eclipse.

Humans have been alternatively amused, puzzled, bewildered and sometimes even terrified at the sight of this celestial phenomenon. A range of social and cultural reactions accompanies the observation of an eclipse. In ancient Mesopotamia (roughly modern Iraq), eclipses were in fact regarded as omens, as signs of things to come.

Solar and lunar eclipses

For an eclipse to take place, three celestial bodies must find themselves in a straight line within their elliptic orbits. This is called a syzygy, from the Greek word “súzugos,” meaning yoked or paired.

Solar lunar eclipse diagram. Tomruen (Own work) via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

From our viewpoint on Earth, there are two kinds of eclipses: solar and lunar. In a solar eclipse, the moon passes in between the sun and Earth, which results in blocking our view of the sun. In a lunar eclipse, it is the moon that crosses through the shadow of the Earth. A solar eclipse can completely block our view of the sun, but it is usually a brief event and can be observed only in certain areas of the Earth’s surface; what can be viewed as a total eclipse in one’s hometown may just be a partial eclipse a few hundred miles away.

By contrast, a lunar eclipse can be viewed throughout an entire hemisphere of the Earth: the half of the surface of the planet that happens to be on the night side at the time.

Eclipses as omens

More than two thousand years ago, the Babylonians were able to calculate that there were 38 possible eclipses or syzygys within a period of 223 months: that is, about 18 years. This period of 223 months is called a Saros cycle by modern astronomers, and a sequence of eclipses separated by a Saros cycle constitutes a Saros series.

Although scientists now know that the number of lunar and solar eclipses is not exactly the same in every Saros series, one cannot underplay the achievement of Babylonian scholars in understanding this astronomical phenomenon. Their realization of this cycle eventually allowed them to predict the occurrence of an eclipse.

The level of astronomical knowledge achieved in ancient Babylonia (southern Mesopotamia) cannot be separated from the astrological tradition that regarded eclipses as omens: Astronomy and astrology were then two sides of the same coin.

Rituals to preempt royal fate

According to Babylonian scholars, eclipses could foretell the death of the king. The conditions for an omen to be considered as such were not simple. For instance, according to a famous astronomical work known by its initial words, “Enūma Anu Enlil” – “When (the gods) Anu and Enlil” – if Jupiter was visible during the eclipse, the king was safe. Lunar eclipses seem to have been of particular concern for the well-being and survival of the king.

In order to preempt the monarch’s fate, a mechanism was devised: the “substitute king ritual,” or “šar pūhi.” There are over 30 mentions of this ritual in various letters from Assyria (northern Mesopotamia), dating to the first millennium B.C. Earlier references to a similar ritual have also been found in texts in Hittite, the Indo-European language for which we have the earliest written records, dating to second-millennium Anatolia – modern-day Turkey.

Saving the king

In this ritual, a person would be chosen to replace the king. He would be dressed like the king and placed on the throne. To avoid confusion with a real coronation, all this would occur alongside the recitation of the negative omen triggered by the observation of the eclipse.

The real king would keep a low profile and avoid being seen. If no additional negative portents were observed, the substitute king was put to death, therefore fulfilling the prophetic reading of the celestial omen while saving the life of the real king. This ritual would take place when an eclipse was observed or even predicted, something that became possible to do in later periods.

The presence of this ritual among the corpus of Hittite texts in second-millennium Anatolia has led to the assumption that it must have existed already in Mesopotamia during the first half of the second millennium B.C.

A legend

Although omens predicting the death of the king are already known for this earlier period, the truth is that the main basis for such an assumption is an interesting story preserved only in a much later, first-millennium composition known by modern scholars as the “Chronicle of Early Kings.”

According to this late chronicle, a king of the city of Isin (modern Išān Bahrīyāt, about 125 miles to the southeast of Baghdad), Erra-imitti, was replaced by a gardener called Enlil-bani as part of a substitute king ritual. Luckily for this gardener, the real king died while eating hot soup, so the gardener remained on the throne and became king for good.

The fact is that these two kings, Erra-imitti and Enlil-bani, did exist and reigned successively in Isin during the 19th century B.C. The story, however, as told in the late “Chronicle of Early Kings,” bears all the trademarks of a legend. The story was probably devised to explain a dynastic switch, in which the royal office passed from one family or lineage to another, instead of following the usual father-son line of succession.

Looking for meaning in the skies

A lunar eclipse. Neil Saunders, CC BY-NC-ND

Mesopotamia was not unique in this regard. For instance, a chronicle of early China known as the “Bamboo Annals” (竹書紀年 Zhúshū Jìnián) refers to a total lunar eclipse that took place in 1059 B.C., during the reign of the last king of the Shang dynasty. This eclipse was regarded as a sign by a vassal king, Wen of the Zhou dynasty, to challenge his Shang overlord.

In the later account contained in the “Bamboo Annals,” an eclipse would have triggered the political and military events that marked the transition from the Shang to the Zhou dynasty in ancient China. As in the case of the Babylonian “Chronicle of Early Kings,” the “Bamboo Annals” are a history of earlier periods compiled at a later time. The “Bamboo Annals” were allegedly found in a tomb about A.D. 280, but they purport to date to the reign of the King Xiang of Wei, who died in 296 B.C.

The complexity of human events is rarely constrained and determined by one single factor. Nevertheless, whether in ancient Mesopotamia or in early China, eclipses and other omens provided contemporary justifications, or after-the-fact explanations, for an entangled set of variables that decided a specific course of history.

Even if they mix astronomy and astrology, or history with legend, humans have been preoccupied with the inescapable anomaly embodied by an eclipse for as long as they have looked at the sky.

Gonzalo Rubio does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond the academic appointment above.

0 notes