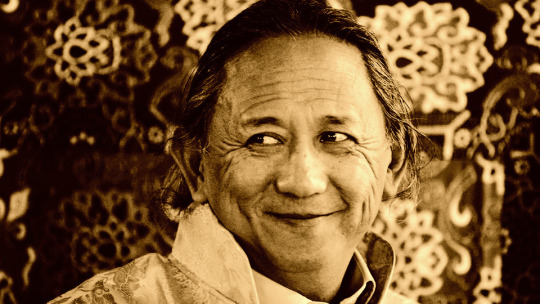

#dzigar kongtrul rinpoche

Text

We are always seeking something from the outside and forgetting that our fundamental well-being and strength depend on how we relate to our own minds.

— Dzigar Kongtrul Rinpoche, “Old Relationships, New Possibilities” (Winter 2008 issue of Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. The Tricycle Foundation) (via Alive on All Channels)

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

"One of the greatest things about being a dharma practitioner is that you are encouraged, and you are taught that you have room to be honest, deadly honest, about your downfalls and flaws, but without that being painful. Why is it not painful? Because we are taught the view of emptiness and egolessness. There is no self to beat up in that view. So we can be that honest." - Dzigar Kongtrul Rinpoche

39 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Agility of mind leads to transformation.

Dzigar Kongtrul Rinpoche

1 note

·

View note

Text

All living beings seek happiness and the causes and conditions of happiness and wish to avoid suffering and the causes and conditions of suffering. That natural intelligence is a sign of the buddhanature and is known as the natural disposition toward enlightenment.

The activation of that natural disposition into actual movement toward enlightenment starts when you begin to connect the dots, meaning, when you identify the cause of suffering and pain and the cause of happiness and liberation and begin to take steps to overcome that which creates suffering. That is known as the development disposition, and that is what fuels our path and is what begins to blossom by entering the path to awakening.

— Dzigar Kongtrul Rinpoche

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

"On the Buddhist path, rather than trying to protect ourselves from our own mind, we actively investigate mind in order to understand how it works. We often have to be quite critical of our habits. We have to look at our faults, including our aggression. We have to examine our neuroses. There is research to be done! If we respond with revulsion toward our mind and its activities, this inquiry cannot take place. We need to understand the mechanics of aggression and learn to reflect in a nonjudgmental way. We may be hard on ourselves, thinking we have anger-management problems' or calling ourselves 'a lost cause.' But in this way, we just sidestep really looking. We need to look at the mind without judgments of good or bad. At the same time, we need to understand how good and bad are defined by virtue of how they function to create happiness and pain. In other words, we need to sort things out with wisdom mind and bring them into review.

All the Buddha's teachings find roots in non-violence: nonviolence toward others, nonviolence toward ourselves, and non-violence even toward negative emotions. It is important that we have a taste of the peace that comes from nonaggression. The dualistic tendency to push things away poses the biggest problem for us. We have so many wants and 'unwants'.

...but how wonderful - there is room

for all. When we begin to understand our mind's habits, we have the leverage to slowly and steadily outsmart them." -

Dzigar Kongtrul Rinpoche, in "Light Comes Through"

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

"A few hundred years after the time of the Buddha, the glorious emperor Ashoka ruled most of the Indian subcontinent. He had expanded his ego's kingdom in a way that few people in history have. Then one day he noticed that a Buddhist monk was giving teachings to one of his wives who treated the monk with great devotion. Ashoka became extremely jealous and decided to have the monk executed right away. But the monk showed no fear. This confounded Ashoka, who had been in many battles and had never seen anyone, not even the bravest warrior, show such fearlessness. The intense emotional pain of jealousy that Ashoka suffered and the intriguing mystery of the monk's fearless mind made the emperor turn inward and self-reflect. He realized that there was a different way of looking at life. This monk had something important to teach him. So he started to receive teachings from the monk's own teacher and eventually became one of the greatest patrons of Buddhism the world has ever known."

~ Dzigar Kongtrul, The Peaceful Heart

Dzigar Kongtrul Rinpoche

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

We cannot eliminate all of the challenges or obstacles in life—our own or anyone else’s. We can only learn to rise to the occasion and face them.

—Dzigar Kongtrul Rinpoche, “Old Relationships, New Responsibilities”

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

No matter your opinions on Tulpas can people please stop calling Sprul Sku a dead practice because it is very much not.

There are multiple living practicioners today (1) and many have faced persecution for their practice, some having to flee their home countries (2). It is extremely disrespectful to call it a dead practice especially in with practicioners actively fighting to keep it alive.

1. The 7th Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche has multiple books and is a known public speaker, Jigmet Pema Wangchen is the the 12th Gyalwang Drukpa and a noted humanitarian. The third Dzigar Kongtrul was the teacher of Pema Chödrön whose a well known Buddhist nun and author.

2. Though not the only country to do so China has a long history of attempting to suppress Tibetan culture and Tibetan Buddhism and continues to do so to this day. Here are a few articles on what's happen, please understand that by saying sprul sku is a dead practice you are directly helping this suppression:

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/world/monitoring/253345.stm

https://www.asianews.it/index.php?l=en&art=10025&size=A

https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/07/30/illegal-organizations/chinas-crackdown-tibetan-social-groups

- Scarlet

#anti tulpa#pro tulpa#syscourse#actually plural#actually multiple#im not sure what tags to use to get this seen so hopefully these work#collective chatter

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Don't think you have to leave most of your mind behind when you become a practitioner. That would be a wrong view of the spiritual path. The ground of practice is your direct experience - regardless of its content. You don't have to act out or indulge in these emotions. Just give them space and see them clearly.

~ Dzigar Kongtrul Rinpoche

別以為當成為一名修行者時,你必須把大部分的思想拋在腦後。那將是對修行之道的錯誤看法。修行的基礎是你的直接體驗——無論其內容如何。你不必表現出來或沉迷於這些情緒。只要給它們空間,清楚地看到它們。

~ 智嘎康楚仁波切

0 notes

Text

The Past Has Already Been Lived

Chinese New Year Parade, Las Vegas. iphone 12 Pro iColorama app

The past is important, but not as important as the present and the future.

The past has already been lived.

It doesn’t have to be relived.

To sacrifice the present and the future by reliving past injuries is not the way of the sages.

— Dzigar Kongtrul Rinpoche, Opening the Injured Heart

‘Start Again,’ I Heard Them SayAugust 2,…

View On WordPress

#Ageing#change#Destiny#enlightenment#Loss#Mojave Desert#New Year#purpose#Reflection#Regret#selfhelp#success#wisdom

0 notes

Text

As you age, you must aim to rejoice more and more. Rejoice in the blessings you have in your life, in the goodness you see in the world around you, free of envy, competitiveness, aggression, or jealousy; this makes the whole world your personal delight.

There is much more satisfaction in rejoicing in the goodness and plenty of the world than in possessing it all yourself.

~ Dzigar Kongtrul Rinpoche

0 notes

Text

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

The notion of enlightenment means, “not bound”. Not bound to what? Not bound to one’s own mind in ordinary ways; not bound in confusion to all the suffering that one’s mind has produced and is experiencing. So the notion of enlightenment is not something outside of one’s own mind.

We cannot imagine achieving enlightenment, let alone perfecting any of the qualities of buddhahood, if we hold to ourselves as who we think we are right now — with the way we think and the validity that we give to our own mind and its existence

— Dzigar Kongtrul Rinpoche

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Sometimes aggression makes people appear powerful. They may get their way and rise to a high position by shouting and intimidating others when their demands aren't met. Many are attracted to that kind of power. But if you take a closer look, these angry people are always having to clean up their messes. They have to spend their energy making amends, giving gifts, mustering smiles, and so on. If this becomes a pattern, they find that all their mental and emotional space is being taken up by the heat of anger and its many repercussions. This makes it difficult for them to be productive and enjoy their leisure time." - Dzigar Kongtrul Rinpoche in the book "Peaceful Heart"

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Turn Your Thinking Upside Down

An article by Pema Chödrön

We base our lives on seeking happiness and avoiding suffering, but the best thing we can do for ourselves is to turn this whole way of thinking upside down.

On a very basic level all beings think that they should be happy. When life becomes difficult or painful, we feel that something has gone wrong. This wouldn’t be a big problem except for the fact that when we feel something’s gone wrong, we’re willing to do anything to feel OK again. Even start a fight.

According to the Buddhist teachings, difficulty is inevitable in human life. For one thing, we cannot escape the reality of death. But there are also the realities of aging, of illness, of not getting what we want, and of getting what we don’t want. These kinds of difficulties are facts of life. Even if you were the Buddha himself, if you were a fully enlightened person, you would experience death, illness, aging, and sorrow at losing what you love. All of these things would happen to you. If you got burned or cut, it would hurt.

But the Buddhist teachings also say that this is not really what causes us misery in our lives. What causes misery is always trying to get away from the facts of life, always trying to avoid pain and seek happiness—this sense of ours that there could be lasting security and happiness available to us if we could only do the right thing.

“Suffering can humble us. Even the most arrogant among us can be softened by the loss of someone dear.”

In this very lifetime we can do ourselves and this planet a great favor and turn this very old way of thinking upside down. As Shantideva, author of Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life, points out, suffering has a great deal to teach us. If we use the opportunity when it arises, suffering will motivate us to look for answers. Many people, including myself, came to the spiritual path because of deep unhappiness. Suffering can also teach us empathy for others who are in the same boat. Furthermore, suffering can humble us. Even the most arrogant among us can be softened by the loss of someone dear.

Yet it is so basic in us to feel that things should go well for us, and that if we start to feel depressed, lonely, or inadequate, there’s been some kind of mistake or we’ve lost it. In reality, when you feel depressed, lonely, betrayed, or any unwanted feelings, this is an important moment on the spiritual path. This is where real transformation can take place.

As long as we’re caught up in always looking for certainty and happiness, rather than honoring the taste and smell and quality of exactly what is happening, as long as we’re always running away from discomfort, we’re going to be caught in a cycle of unhappiness and disappointment, and we will feel weaker and weaker. This way of seeing helps us to develop inner strength.

And what’s especially encouraging is the view that inner strength is available to us at just the moment when we think we’ve hit the bottom, when things are at their worst. Instead of asking ourselves, “How can I find security and happiness?” we could ask ourselves, “Can I touch the center of my pain? Can I sit with suffering, both yours and mine, without trying to make it go away? Can I stay present to the ache of loss or disgrace—disappointment in all its many forms—and let it open me?” This is the trick.

There are various ways to view what happens when we feel threatened. In times of distress—of rage, of frustration, of failure—we can look at how we get hooked and how shenpa escalates. The usual translation of shenpa is “attachment,” but this doesn’t adequately express the full meaning. I think of shenpa as “getting hooked.” Another definition, used by Dzigar Kongtrul Rinpoche, is the “charge”—the charge behind our thoughts and words and actions, the charge behind “like” and “don’t like.”

It can also be helpful to shift our focus and look at how we put up barriers. In these moments we can observe how we withdraw and become self-absorbed. We become dry, sour, afraid; we crumble, or harden out of fear that more pain is coming. In some old familiar way, we automatically erect a protective shield and our self-centeredness intensifies.

“We can become intimate with just how we hide out, doze off, freeze up. And that intimacy, coming to know these barriers so well, is what begins to dismantle them.”

But this is the very same moment when we could do something different. Right on the spot, through practice, we can get very familiar with the barriers that we put up around our hearts and around our whole being. We can become intimate with just how we hide out, doze off, freeze up. And that intimacy, coming to know these barriers so well, is what begins to dismantle them. Amazingly, when we give them our full attention they start to fall apart.

Ultimately all the practices I have mentioned are simply ways we can go about dissolving these barriers. Whether it’s learning to be present through sitting meditation, acknowledging shenpa, or practicing patience, these are methods for dissolving the protective walls that we automatically put up.

When we’re putting up the barriers and the sense of “me” as separate from “you” gets stronger, right there in the midst of difficulty and pain, the whole thing could turn around simply by not erecting barriers; simply by staying open to the difficulty, to the feelings that you’re going through; simply by not talking to ourselves about what’s happening. That is a revolutionary step. Becoming intimate with pain is the key to changing at the core of our being—staying open to everything we experience, letting the sharpness of difficult times pierce us to the heart, letting these times open us, humble us, and make us wiser and more brave.

Let difficulty transform you. And it will. In my experience, we just need help in learning how not to run away.

If we’re ready to try staying present with our pain, one of the greatest supports we could ever find is to cultivate the warmth and simplicity of bodhichitta. The word bodhichitta has many translations, but probably the most common one is “awakened heart.” The word refers to a longing to wake up from ignorance and delusion in order to help others do the same. Putting our personal awakening in a larger—even planetary—framework makes a significant difference. It gives us a vaster perspective on why we would do this often difficult work.

There are two kinds of bodhichitta: relative and absolute. Relative bodhichitta includes compassion and maitri. Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche translated maitri as “unconditional friendliness with oneself.” This unconditional friendliness means having an unbiased relationship with all the parts of your being. So, in the context of working with pain, this means making an intimate, compassionate heart-relationship with all those parts of ourselves we generally don’t want to touch.

Some people find the teachings I offer helpful because I encourage them to be kind to themselves, but this does not mean pampering our neurosis. The kindness that I learned from my teachers, and that I wish so much to convey to other people, is kindness toward all qualities of our being. The qualities that are the toughest to be kind to are the painful parts, where we feel ashamed, as if we don’t belong, as if we’ve just blown it, when things are falling apart for us. Maitri means sticking with ourselves when we don’t have anything, when we feel like a loser. And it becomes the basis for extending the same unconditional friendliness to others.

If there are whole parts of yourself that you are always running from, that you even feel justified in running from, then you’re going to run from anything that brings you into contact with your feelings of insecurity.

“I’m here to tell you that the path to peace is right there, when you want to get away.”

And have you noticed how often these parts of ourselves get touched? The closer you get to a situation or a person, the more these feelings arise. Often when you’re in a relationship it starts off great, but when it gets intimate and begins to bring out your neurosis, you just want to get out of there.

So I’m here to tell you that the path to peace is right there, when you want to get away. You can cruise through life not letting anything touch you, but if you really want to live fully, if you want to enter into life, enter into genuine relationships with other people, with animals, with the world situation, you’re definitely going to have the experience of feeling provoked, of getting hooked, of shenpa. You’re not just going to feel bliss. The message is that when those feelings emerge, this is not a failure. This is the chance to cultivate maitri, unconditional friendliness toward your perfect and imperfect self.

Relative bodhichitta also includes awakening compassion. One of the meanings of compassion is “suffering with,” being willing to suffer with other people. This means that to the degree you can work with the wholeness of your being—your prejudices, your feelings of failure, your self-pity, your depression, your rage, your addictions—the more you will connect with other people out of that wholeness. And it will be a relationship between equals. You’ll be able to feel the pain of other people as your own pain. And you’ll be able to feel your own pain and know that it’s shared by millions.

Absolute bodhichitta, also known as shunyata, is the open dimension of our being, the completely wide-open heart and mind. Without labels of “you” and “me,” “enemy” and “friend,” absolute bodhichitta is always here. Cultivating absolute bodhichitta means having a relationship with the world that is nonconceptual, that is unprejudiced, having a direct, unedited relationship with reality.

That’s the value of sitting meditation practice. You train in coming back to the unadorned present moment again and again. Whatever thoughts arise in your mind, you regard them with equanimity and you learn to let them dissolve. There is no rejection of the thoughts and emotions that come up; rather, we begin to realize that thoughts and emotions are not as solid as we always take them to be.

It takes bravery to train in unconditional friendliness, it takes bravery to train in “suffering with,” it takes bravery to stay with pain when it arises and not run or erect barriers. It takes bravery to not bite the hook and get swept away. But as we do, the absolute bodhichitta realization, the experience of how open and unfettered our minds really are, begins to dawn on us. As a result of becoming more comfortable with the ups and the downs of our ordinary human life, this realization grows stronger.

“We may still get betrayed, may still be hated. We may still feel confused and sad. What we won’t do is bite the hook.”

We start with taking a close look at our predictable tendency to get hooked, to separate ourselves, to withdraw into ourselves and put up walls. As we become intimate with these tendencies, they gradually become more transparent, and we see that there’s actually space, there is unlimited, accommodating space. This does not mean that then you live in lasting happiness and comfort. That spaciousness includes pain.

We may still get betrayed, may still be hated. We may still feel confused and sad. What we won’t do is bite the hook. Pleasant happens. Unpleasant happens. Neutral happens. What we gradually learn is to not move away from being fully present. We need to train at this very basic level because of the widespread suffering in the world. If we aren’t training inch by inch, one moment at a time, in overcoming our fear of pain, then we’ll be very limited in how much we can help. We’ll be limited in helping ourselves, and limited in helping anybody else. So let’s start with ourselves, just as we are, here and now.

Excerpted from Practicing Peace, by Pema Chödrön. © 2006 Pema Chödrön. Reprinted with permission of Shambhala Publications. Published in Lion's Roar Magazine

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

It Gets Easier Once we taste the freedom that comes with independence, it gets easier. We realize how much we have lost by desperately holding on, and we know how much there is to gain through disengaging from confusion. We can do this while expanding our most precious qualities: our good heart and our compassion for others. — Dzigar Kongtrul Rinpoche, “Old Relationships, New Possibilities” (at New Haven Zen Center) https://www.instagram.com/p/CjAs8egu6Fq/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes