#duke of reichstadt

Text

Yesterday was Napoleon II's birthday but I had completely forgotten to draw anything for it, so here's a very late, very rushed birthday drawing for l'aiglon:

(I tried to be experimental with light and colour and it didn't really turn out well, but like I said this was extremely rushed 😭)

#happy birthday baby boy <3#Napoleon ii#Duke of reichstadt#king of rome#history#french history#napoleon#art#my art

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

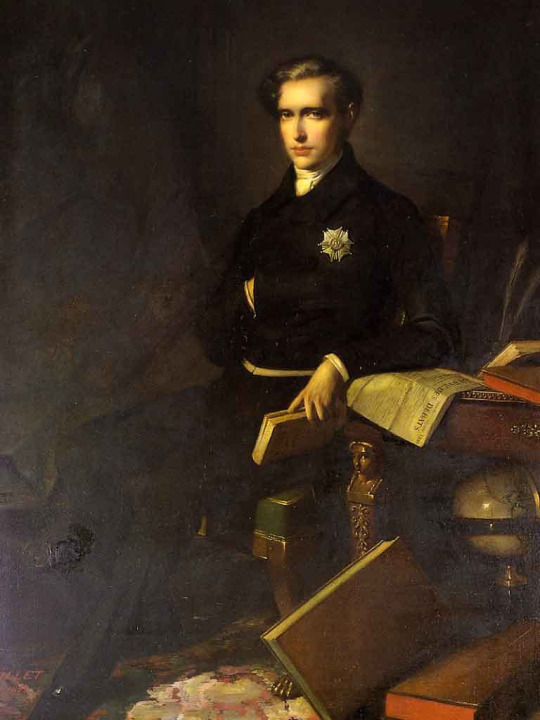

You are traveling near two derelict Napoleon breeding farms that @isthenapoleoncute always complains about and you come to a fork in the road. One direction will lead you to a farm where Napoleon IIs tell nothing but lies, and in the other a farm where the Napoleon II’s always tell the truth. You have business with the farm where the Napoleons tell the truth. Two Napoleon IIs are standing by the fork.

One is dressed like the Napoleon II on the left. The other, like the right.

How can you tell which one is from the farm of lying Napoleon IIs and which one is from the farm of truth telling Napoleon IIs?!

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Letizia’s letter on learning of the death of her grandson, Napoleon II

Addressed to Hortense de Beauharnais

Year: 1832

“I have been given your letter of August 17th, which found me ill and overcome with grief. I try to take courage, but there are some sorrows which are impossible to endure. The blow I have just sustained is one of those. It has re-opened all the barely healed wounds of my heart, and every day I learn new details which add to my sorrow. . . . You will readily appreciate that my health has been greatly affected. It was already very poor, and this fresh grief has made it worse.”

This passing came around the same time as a number of other deaths in the family. Joseph Bonaparte wrote to his mother: “It is our fate to enjoy a little and to suffer much.”

Source: Alain Decaux, Napoleon’s mother

#Letizia Bonaparte#Letizia#Napoleon’s mother#Napoleon ii#Duke of reichstadt#king of Rome#napoleon#napoleonic era#napoleonic#napoleon bonaparte#first french empire#19th century#french empire#Joseph Bonaparte#Joseph#hortense#hortense de beauharnais#letter#Alain Decaux#Decaux

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

It is known when the rumors about Archduke Maximilian's paternity began? Was it right from his conception and birth or when Napoleon III offered him to became the Emperor of Mexico? Was it has his dethronement and execution? Was it along afterwards? If there was prominent during his lifetime, it is know what his action was or his parents or his wife Empress Carlota?

Sorry, I'm totally out of my depths here. I am only dimly aware of these rumours myself, and the one biography of Napoleon II/Duke of Reichstadt that I have read dismissed the idea out of hand.

Maybe @archduchessofnowhere could help?

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

My relations with the Duke of Reichstadt (2/?)

Hi guys! Here is the second part for this series! Thanks for anyone who supported the first post! Making content about the King of Rome/Napoleon II always makes me happy and fills my heart with joy. I hope you enjoy it!

The next day, that is to say, June 24, I addressed the following lines to Count Dietrichstein: "I have been pleasantly impressed by the spirit, knowledge and judgment that your august pupil displayed in yesterday's interview; therefore I deeply regret to have neglected in the past the opportunity of an interview that honored and delighted me as much as yesterday's. When we bear such a great name and know from childhood that we are called to such high destinies; when, moreover, we are so well gifted like Your Highness and we live in times similar to our own, it is because Providence has appointed us for great things. Ordinary men, regardless of the rank in which they have been placed by birth, aspire and achieve only ordinary things. But men out of line, and among these I dare to count the eminent student of Your Excellency, they have duties towards society and history, from which they are not allowed to evade. I look forward to the time when I am granted to renew my visit of yesterday, and I desire nothing more ardently than to maintain His Highness in the opinion that he has formed of me and to which our interview the day before, as well as the favorable idea that he was able to conceive the content of some of my military writings, will certainly contribute. only to a small extent. Please accept with my best wishes, etc."

In response to this letter, I received a very friendly invitation for the next morning. This one came across the kindest orders of His Excellency the Emperor, who called me to met him that same morning. On my arrival, I saw so many people waiting in the antechambers that I thought I had the patience to see the duke. We talked to each other with all the grace of people who understand each other. I again expressed my wish to see him claim the throne of Greece, free to set whatever conditions he saw fit. This idea made him smile; but I clearly noticed that his desires and hopes were tending higher, moreover, he was trying to abuse of himself, pretending that he was too young by a few years to wear the Hellenic crown, and seeming to fear that we would not let him rule alone. Then, abruptly, he returned with marked interest to the duties and qualities of the commander-in-chief. His eyes sparkled, his cheeks burned.

Count Dietrichstein left us alone for a few moments, and the young prince held me tightly with both hands:

"Speak to me frankly," he exclaimed, "do I have some merit, and am I called to a great future, or is there nothing in me that is worthy of ending up like this? What do you think, what do you hope for my future? What will happen to the son of the great emperor? Will Europe support him in taking some kind of independent position? How do I balance my French duty with my Austrian duty? Yes, if France called me, not the France of anarchy, but the one that has faith in the Imperial principle, I would run to her, and if Europe tried to expel me from my father's throne, I would draw the sword against all Europe. But is there an imperial France today? I don't know! A few isolated voices, a few voices without influence, they cannot carry any weight. Such serious resolutions deserve and require more solid foundations. If my destiny is never to return to France, I seriously wish to become another Prince Eugene for Austria. I love my grandfather; I feel that I am a member of his family, and for Austria I would gladly draw my sword against the whole world, except France."

He spoke to me as one speaks to a confessor, and I received his confidences in the same way. These were projects, of course, very legitimate in themselves and that could only become dangerous in a single hypothesis, the realization of which, in truth, was not at all impossible, but seemed at least very distant. Once again he gave vent to the feelings of filial affection. He said that no one had understood his father; that it was pitiful, that it was slanderous not to give his actions any motive other than ambition; that all his life and all his conduct had been consumed by the great and salutary projects which he had conceived for the happiness of Europe; that Austria, in particular, had ignored him and his own interests; that he had played into the hands of the Russians. The duke added that he wanted nothing more than to earn his spurs by fighting them. He spoke with warmth, but also with that frank and intimate conviction of youth. Then, hearing Count Dietrichstein's voice in the next room, he abruptly changed the subject to address this question to me:

— What memory do you have of my father in Egypt?

— The memory of a great figure — I answered.

— I understand, if you are talking about Ibrahim, the viceroy; but the populations? They have not yet returned from their surprise; this astonishment, however, has not been followed by any irritation, for the Arabs and the Turks, though they have the same faith, do not get along with each other, and one heavy yoke succeeded another still heavier.

— Yes, this is an explanation; but the masses see in a great man only a freak of nature, a meteor that shines for a moment and immediately disappears.

At that moment he exclaimed again:

— Oh! If only you stayed with me; but before you, opens a path full of smiling perspectives capable of tempting you.

I shook his hand and said; "We'll talk about this later."

And we separated after kissing.

Only three days after this interview, and since in the meantime I had only been able to meet the Duke under unfavorable circumstances, I had a special interview with him that lasted for more than two hours. On the morning of that day, Count Dietrichstein had come to visit me and had complained, with the bad temper of a mother, about the duke's stubbornness and his aversion to any study except military art and mathematics; there wasn't even a german spelling that he didn't want to treat his way.

The count recognized that his student had a good nature, which, however, was hardened by indocility and pride. The duke, to whom I shared, insofar as I thought useful, these reproaches, did full justice to the count, especially to his excellent heart, but in short he praised nothing else in him. He had a definite opinion of his entourage, and he spoke to me frankly and forthrightly about the Emperor and the court, with the accent of an upright heart, but also of self-assured intelligence. He loved his grandfather with a filial love; for from the day he was brought to Vienna as a child, he had found in him the tenderness of a father. He had his ittle corner to play in the Emperor's room, spent half the days by his side, ate with him when the Emperor dined alone, shared with him the pleasures of the resort, finally grew close to him, like a branch grafted onto a foreign stump. He told me all this; but he added that he had not forgotten for a moment whose day he kept and in what place his father's ashes lay. He painted the court for me in colors that were often not very favorable, revealing, being honest, only the nature, the judgment, the heart, the garb of Archduke John. It was impossible for me to dispute the accuracy of his assessments. In many people he thought precisely like me, and, inside him, he did not compromise more than I did.

Like the agitated traveler who sighs after a fountain of living water, he thirsted for information about the situation in Europe. I told him everything I knew and thought. Although in my opinion the fall of Charles X was inevitable, I was far from expecting that it would be soon; as for Louis Philippe and the younger branch, I didn't even think about it.

Rather, I believed in a period of anarchy, out of which the new government would emerge. To whom would this government fall divided? Could it be the Napoleonic party? This point was beyond my judgment. I could give the duke no other advice than to strengthen his judgment by reading the history of past times, in order to appreciate contemporary events; thus learning to distinguish reality and truth from appearances and illusions, above all, meditating on his father's story, realizing the current situation of the world, which contains in germ the near future that will be the result by virtue of the irresistible logic of things; furthermore, to affirm his person in the army and in the diplomatic spheres, to attract to him capable men of great experience, of whom I named several, finally, to enlighten himself by all possible means on the internal situation of France.

With a wave of his hand, he indicated his book collection, which contained several hundred volumes. They were historical works and memoirs, all related to the war and his father.

This precious treasure was increasing day by day, to which no obstacle was placed. I promised him that I would choose the best among these works, that I would be a very devoted friend of his and that I would complement with my reflections the observations that the general state of politics would suggest to him; finally I begged him not to confuse legitimate desires with achievable desires, but to never lose sight of them. He was so well trained by his young enthusiasm that he called me his Posa(1).

I replied to him:

— That's the language of a twenty-year-old. Is there any consistency in this will? That is what, at the moment, it is difficult for me to know.”

My defiance seemed to sadden him. He kissed me, telling me:

— You're right, I don't deserve you to see in me the son of Napoleon.

I comforted him with these words:

— Your Posa, yes, but on the condition that you do not imitate don Carlos; I will be for your whole life, and I hope, that it will be a glorious life.

He reviewed the entire series of steps to be taken so that, once his military house was established, it could be linked to his person. We had time ahead of us in this regard. He thought he would achieve his ends through his grandfather, the Emperor. I authorized him to do everything he could for this purpose. As for him, he no longer doubted success.

(1) Allusion to the tragedy of Schiller Don Carlos.

Source: Mes relations avec le duc de Reichstadt : mémoire posthume / par le comte de Prokesch-Osten,. . . ; traduit de l’allemand [par A. de Prokesch-Osten fils]. (s. f.). Gallica. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6536278r/f39.item.zoom

#duke of reichstadt#l'aiglon#napoleon ii#the king of rome#napoleon's son#napoleon's family#anton prokesch-osten#hasburg#memoirs

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Napoleon II, styled King of Rome, later Duke of Reichstadt, by Thomas Lawrence, 1818-1819

Napoleon’s only legitimate child, Napoleon François Charles Joseph Bonaparte, was born at the Tuileries Palace on March 20, 1811, to all the splendor of the French Imperial Court. His birth was a touch-and-go affair. The doctor feared that either Napoleon’s wife, Marie Louise, or the baby might die. Napoleon said he would have preferred being at a battle.

The baby was given the title of King of Rome. He was later known as Napoleon II, the Prince of Parma, and the Duke of Reichstadt. He did not hold all of those titles at the same time, and you can tell whether someone was a supporter of Napoleon based on how they referred to the boy after 1815. His nickname was l’Aiglon, or the Eaglet (one of Napoleon’s symbols was the eagle).

He led a short, sad life, living in exile from France and dying of tuberculosis at the age of 21. For details, see “Napoleon II: Napoleon’s Son, the King of Rome.”

39 notes

·

View notes

Note

I was reading up on Napoleon II because your posts about him got me interested, and found out there's a quite well-regarded play about him by Edmond Rostand (of Cyrano de Bergerac fame). Have you read it? And if so, what were your thoughts? Did you like it, was it true to what you've read about the actual Franz, etc.? Did you feel like Rostand did justice to his story?

Thank you for reading my posts! I'm so glad my biography recaps are getting people interested in Franz. I really appreciate it. :)

Truth be told, I've avoided Rostand's L'Aiglon until now because late Victorian drama makes me break out in hives. But I read it, just now, just for you! So I could actually say something about it! And... well...

It might have been well-received back in 1900, but the whole play's aged about as well as milk. It was written as a Sarah Bernhardt vehicle, and IMO there is very little of Franz in the main character: it's Sarah Bernhardt grandstanding, from beginning to end. (I've watched a lot of her movies-- many of them are on Youtube-- and she has a very distinct delivery and style, which is replicated faithfully in the play.) On the whole, I found it tedious, affected and extremely melodramatic. There's not a lot of depth to any of the characters, just lots of florid speechifying (and it even rhymes in the original French, God help me). Franz yearns to be like his dad and rule France. Metternich is a royalist Snidely Whiplash. Prokesch is a faithful sidekick. Countess Camarata is Cool Action Girl and Marie Louise is a shallow twit. I mean, sure, these depictions aren't so far off from reality, but it would have been nice to have some degree of complexity and nuance.

Rostand did do some research, and there are some flashes of wit and insight. I particularly liked this speech here:

I like that "but," I hope you feel its value!

Good Lord, I'm not a prisoner, "but"—that's all!

"But"—not a prisoner, "but"—that is the word,

The formula! A prisoner? Oh, not a moment!

"But" there are always people at my heels.

A prisoner? Not I! You know I'm not;

"But" if I risk a stroll across the park

A hidden eye blossoms behind each leaf.

Of course not prisoner, "but" let anyone

Seek private speech with me, beneath each hedge

Up springs the mushroom ear. I'm truly not

A prisoner, "but" when I ride, I feel

The delicate attention of an escort.

I'm not the least bit in the world a prisoner,

"But" I'm the second to unseal my letters.

Not at all prisoner, "but" at night they post

A lackey at my door—look! there he goes.

I, Duke of Reichstadt, prisoner? Never! never!

I, prisoner? No! I'm not a prisoner—"but"—!

This rings true to me-- and there are some fun scenes where Franz confronts his mother and his grandfather. But then the play devolves into an improbable plot to free Franz where his cousin Camarata dresses up like him and they switch places, and there's a climactic scene where there's a showdown with the chief of police on the field of Wagram, and Franz has a vision of all the men who died at Wagram, and then he's forced to join his own Austrian regiment after he almost attacks them in his delirium. Okay then.

He dies in the last act, and all his family show up to attend his death, which is so far from what actually happened I wanted to go back in time to punch Rostand. While he was dying, Franz actually was deserted by his family, and his mother had to be badgered to show up, which she did at the last minute. (In fact, Franz thought he wasn't dying because his tutor Dietrichstein wasn't there. Dietrichstein claimed Franz was just like a son to him, but left, like everyone else, to leave Franz attended only by servants.) It was all so grim and awful, and this was just... a typical Victorian death scene, out of Camille or Uncle Tom's Cabin. I found it underwhelming as well as infuriating.

There's also the issue of the role was written to be played by an actress (Sarah Bernhardt in Paris, with Maude Adams taking over the role in New York). As I was reading it, I couldn't help but think how much the real Franz would have hated this. He was always chomping at the bit to prove himself as a soldier and go off into combat-- the play leans hard into the depiction of him as a pretty, tragic, frustrated martyr, and I don't think he would have liked that. His depression, his bitterness and rage are all sugar-coated. His stoicism is non-existent. Even his greatest quotes (like the famous "Ma naissance et ma mort, voilà toute mon histoire. Entre mon berceau et ma tombe il y a un grand zéro") are gussied up and drawn out in an elaborate set-piece involving his cradle being physically brought to his death-bed. It's bizarre and frankly a bit tasteless.

I think the play would have been stronger if Rostand had downplayed the fantasy swashbuckling elements, but I guess that was his brand. Personally, I think a psychological thriller about grooming and abuse would have been more apropos for Franz's life, but I'm a 21st century person with 21st century tastes. L'Aiglon is definitely a product of its time, no more, no less.

Anyway, thanks for the ask! Sorry about the rant. 😬

#l'aiglon#edmond rostand#napoleon II#duke of reichstadt#napoleon bonaparte#napoleon#rant#god i have so many thoughts about this#also the weirdness of rostand writing a fantasy swashbuckler about a guy who died 68 years before#this wasn't like cyrano#this was well within living memory#this is like someone writing an OTT fantasy about Charles de Gaulle or Princess Margaret#it's so weird

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hector Fleischmann on Marie Louise

Belle Epoque author Hector Fleischmann REALLY doesn’t like Marie Louise, Napoleon’s second wife, and he is not shy about letting you know this. In his very short book “Marie Louise, Libertine,” here is his take on the last correspondence between Marie Louise and Madame Mère, on the death of Franz, aka Napoleon II, the King of Rome, or the Duke of Reichstadt.

* * *

A few weeks of respite still, and the denouement is close. On July 22, at 5:10 a.m., the melancholy destiny of the young man came to an end; the last link that tied Marie-Louise to the memory of Napoleon was broken. This death, which was to strike her with an unparalleled blow, which seemed to take with it all that was to remain of her radiant and happy youth, this death, it is in two small sentences, poor and banal, that she announces it to her father. Here is the bill. It completes her in the moral:

Schoënbrunn, 22 July 1832.

DEAR FATHER, My poor son has just expired at 5 hours 10 minutes. Heaven has answered my prayers and granted him a sweet and peaceful death. I kiss your hands, my dear father, and thank you for all the kindness and affection you have shown him; my heart, full of filial tenderness for you, will be eternally grateful.

Here is what, at the tragic hour of her destiny, this mother finds to mourn her son. Not a cry of the heart in this bill, not a sob from the bowels. She records the death, without more. But what more could we have expected from her? And, in the letter with which she announces to Madam Mother the disastrous news, it is the same peaceful and neutral insignificance, the same monotone, the same nullity: To Madame Mère, in Rome.

MADAME, In the hope of softening the bitterness of the painful news that I am unfortunately in the position of announcing to you, I did not want to yield to anyone the painful task of telling you about it. On Sunday 22nd, at 5 o'clock in the morning, my beloved son, the Duke of Reichstatd (sic), succumbed to his long and cruel sufferings. I had the consolation of being with him in his last moments, and of being able to convince myself that nothing had been neglected to keep him alive. But the help of art was powerless against a chest disease that doctors, from the beginning, have unanimously judged of unanimously judged to be of such a dangerous nature that it was bound to lead my unfortunate son to the grave, at the age when he was giving the best hopes. God has disposed of it! It only remains for us to submit to his supreme will, and to confound our regrets and our tears.

Accept, Madam, in this painful circumstance, the expression of the feelings of attachment and consideration that your affectionate MARIE-LOUISE has devoted to you.

At the castle of Schônbrunn, 23 July 1882.

But one guesses well that this is only a protocol model copied by the mother in mourning.The sentence is pompously and ridiculously rounded, and in it nothing speaks of what is nature.

That more worthy, more noble and more heart-rending, is the letter with which the blind and solitary grandmother answers in her old Roman palace! Here the great Napoleonic tone crushes the sentence, swells it with the captive storm of the enormous contained pain. It is Fesch that the mother of the Emperor charges to write:

Rome, August 6, 1832.

MADAME, In spite of the political blindness which always deprived me of receiving news of the dear child whose loss you want to announce to me, I never ceased to preserve for him the heart of a mother (1). He was still the object of some consolation for me, but to my great age, to my usual and painful infirmities, God wanted to add this blow, a new token of his mercies, in the firm hope that he will have amply compensated, in his glory, the glory of this world. Please, Madam, receive the testimony of my gratitude, for having taken the trouble, in such a painful circumstance, to relieve the bitterness of my soul. Be sure that it will last the rest of my life. As my condition prevents me from signing this letter, allow me to entrust it to my brother.

#marie louise#Madame Mère#napoleon bonaparte#napoleon II#duke of reichstadt#king of rome#hector fleischmann

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brother sent me this picture because "I recognized him because of you." I can't really justify making him get it for me since I have no place for something of that value and fragility- but I thought some of you folks would appreciate the art. "Kister Scheibe from Germany is the brand," bust of "Napoleon II"

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Christmas everyone!

I recently rediscovered the motivation to draw so here is some art of my favourite angsty prince Napoleon II <3

#he was so pretty its unfair#died young from tuberculosis like a true icon#(I am literally obsessed with him)#napoleon ii#duke of reichstadt#napoleon#napoleonic#house of habsburg#my art#art#artists on tumblr#history

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

All I’m saying is that if I were a supervillain, this is how I’d dress

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

The little king of Rome :)

#Duke of reichstadt#king of Rome#Napoleon ii#franz#l’aiglon#eaglet#napoleonic era#napoleon#napoleonic#first french empire#napoleon bonaparte#19th century#french empire#france#print#history#art#Habsburg#habsburgs

13 notes

·

View notes

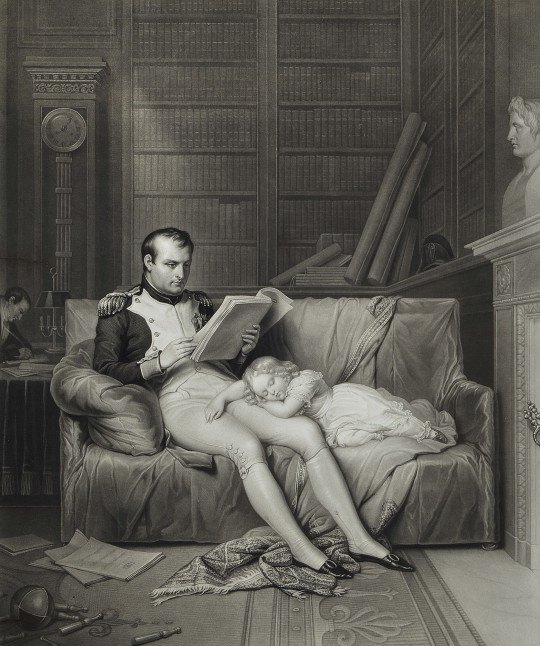

Photo

I’ve come upon several images like the above (engraving by A. V. Sixdeniers), and I’m never quite comfortable with them as I assume they picture a situation that probably never once existed. I also always wondered how much time Napoleon actually even spent under the same roof as his son. Now I see that the French Wikipedia page already has done the maths for me:

1 year, 5 months, 24 days. (Out of not quite 3 years total.)

And on those days, he may have spent how much time with the child? An hour? When the boy was ceremoniously brought before him by his governess to be looked at and talked to, until he was escorted back into his own rooms, where he was surrounded by his own staff of (in 1812) 31 people in total?

I cannot imagine he ever was close to this child. How else could he have written that he rather wanted to see his son in the Seine than in the hands of the Austrians? What father would rather see his son dead?

(Sorry for the random post. Having a bad day today.)

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Metternich: Master of Napoleon's son.

When someone reads about the short and desperate life of Napoleon's son; the King of Rome (Napoleon II, L'aiglon, the Duke of Reichstadt or Franz) soon realizes that, in fact, his life was never his, but Metternich's. Of course, the signs are not at first glance when one barely gets to know the history between these two (and other) characters, even more so knowing that it is said that they only spoke directly with the other on five counted occasions.*¹

We know (or in case you don't, dear reader, you can ask me for the context in private or by asking me to write a blog about it) his governors; his tutors: Count Dietrichstein, captain Foresti and professor Collin -initially - but who was behind all of them? It was Prince Metternich, of course, being he the one who assigned the men to "take care" of the King of Rome, replacing with them his french ladies that the boy loved so much; this way, the Austrian Chancellor guarding since his arrival in Austria the little heir of the "Ogre". It was his work - that is, his careful administration, his observations and movements from far away - that doomed from such a young age the boy who once had everything, only to have nothing the next day.

I bring to you this excerpt from "The King of Rome: Napoleon II, L'Aiglon" by Octave Aubry, which although it isn’t the most descriptive of the point to be discussed in this blog, allows us to peek for a moment at how was the dynamic between Klemens and the boy... or rather, how the chancellor had control of the life of the King of Rome from a distance.

Dietrichstein's reports to Marie Louise make frequent complaints about the child's laziness and ill-will, in spite of his great intelligence. And what can that mean except that he was still resisting?

But under that exacting ferule, gripped in a mold that was crushing his instincts and his will more and more, how could the little King fail to yield in the long run? And in fact he did yield, only to rebel again, be punished once more, and submit a second time. He was rewarded with toys, albums, favorite dishes, sweets, picnics in the country, the circus, a dog, some birds. His grandfather ordered a handsomely chased shotgun for him, just his size, and one day invited him to go hunting, not as an onlooker now, but as a participant. Among Dietrichstein's papers is one of the child's corrected exercises, a little composition describing with a naive importance that day of relaxation and undisguided pleasure.

August 25, 1819.

"To-day I went hunting with my grandfather. We drove as far as the suburbs of Hassendorf where we left the carriage and where the other hunters were waiting for us." I was with my grandfather all the time. We went to the shelters, where I was given a gun, which caused me great pleasure. My grandfather, my Uncle Franz and I went through the shelters to come out on the other side. There my uncle left us to take up the post that had been assigned to him. We waited for the game to come out of the tickets, while the other wing was making a turning movement. After a long wait, the game appeared. I tried a shot, but missed my aim. The other wing was more fortunate than ours. In the beginning my grandfather had no luck, but later on he shot very well. I shot once more. The aged Councilor George, who saw me, came toward me and told me that the shot had frightened him. He took off his hat, showed me the eagle on it, and said he had caught the bird. That made me laugh.”

(…)

Victories over a child sad words indeed to register!

Though, of course, not so much over a child as over the heir of Napoleon Bonaparte! Count Maurice was a prisoner of the method he was applying. His task was to form a character, and he was without character himself. He could be a tutor to the Prince of Parma, but never a friend.

Reports were also regularly sent to Metternich. Everything the child said and did, his work, his amusements, his caprices, his tempers, his tears, his laughs were all set down on huge sheets of paper, and submitted to the Chancellor; and the latter, adjusting his lorgnette, read attentively and classified them in a ponderous file. He seldom referred to such reports at his daily audiences with the Emperor; for he affected a manner of polite indifference toward the young prince.

(…)

But was it not enough for Prince Metternich to have reduced the son of his enemy to such a pass?*² No, that hostage had also to change in appearance as he had changed in dress and decorations. That submissive little Frenchman, so alone and so helpless, who had so stoutly resisted his governors, had to become a spiritless, satisfied subject, without personality and without initiative, a pawn for the Chancellor to manipulate at will on the diplomatic chessboard for, after all, who could say but that he might prove useful later on in some subtle combination? And the Chancellor had eyes which were never so full of tears as not to be able to see far, far into the future.

REFERENCES:

King of Rome: A Biography of Napoleon's Tragic Son André Castelot*¹

This means, reducing him from a crown prince of the French empire, to a prince of Parma, to an Austrian Duke with no political power, or no power at all.*²

Source.

#klemens von metternich#metternich#the king of rome#napoleon ii#duke of reichstadt#l'aiglon#marie louise#francis ii#napoleonic wars

46 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Did you know that a tomb originally intended for Napoleon’s son is sitting in a Canadian cemetery? Napoleon’s son, otherwise known as Napoleon II, the King of Rome or Duke of Reichstadt, died of tuberculosis in Vienna on July 22, 1832, at the age of 21 (see my article about his death). Since his mother, Marie Louise, was the Duchess of Parma, a burial monument for the young man was constructed in Italy. When the Duke of Reichstadt was interred in the Habsburg family crypt at the Capuchin Church in Vienna, the Italian monument was left unused.

Over 20 years later, William Venner, a prosperous merchant from the city of Quebec, came across the magnificently sculpted monument on a business trip to Europe. For details of why and how he brought it back to Canada, and what happened to it afterwards, see “A Tomb for Napoleon’s Son in Canada.”

42 notes

·

View notes