#creates a narrative where they have what more or less boils down to a nuclear family dynamic

Text

Im sorry I love the Zoro Mihawk Perona dynamic but the fandom trend of turning it into “Mihawk adopts Zoro and Perona as children and raises them” makes me want to die

#the fact that it pervades so many au fic is another reason I rarely read one piece aus#first of all I’m not a fan of changing characters’ backstories in such a drastic way#Zoro in canon and Zoro raised as mihawks child would be two very different characters#second of all it’s indicitive of a very odd trend I’ve noticed where fandom takes character with non traditional family dynamics and#creates a narrative where they have what more or less boils down to a nuclear family dynamic#like Zoro already has a family#the straw hats#but bc zoro is one of the only straw hats that you can’t point to a specific character and say ‘that’s his father figure’ ‘thats his sister’#people feel the need to give him a Proper Family with a Dad™️ and a sister™️#which is particularly odd in the Found Family Anime™️#it’s giving superfamily#idk it wouldn’t be bad if it was just a fun thing now and again but god it’s like every single zoro-centric au I see#rambles#sorry I had to rant about this because I just closed out of a fic because of this and I’m just -Keanu smoking meme-#it’s very hard when you dislike a very pervasive fandom trope#if this ends up in the tag and you’re mad about it I’m sorry I don’t want to sensor every word tumblr might pick but I’m not tagging#it myself so please don’t yell at me blame tumblr

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Handmaid’s Tale: Prophecy or Inevitably?

Lydia Cole-November 2018

“Nothing changes instantaneously: in a gradually heating bathtub you’d be boiled to death before you knew it.” It’s amazing how much the world has changed within the past decade, and even within the last few years. Eleven years ago, the first iPhone was released. Ten years ago, Obama was sworn in as the first African American President of the United States. Scientists are close to figuring out how to edit human DNA. Twenty-seven countries have legalized same sex marriage. This is truly the era of change. Sometimes, change happens so quickly that we don’t even really realize that life is different from what it was before.

The Handmaid’s Tale, a thrilling show set in a near future dystopia is all about change, big or small. The story itself isn’t new: it’s been around for over 30 years, since Margaret Atwood’s novel (by the same name) was published in 1985. Bruce Miller has done a better justice to the harrowing themes in Atwood’s novel than any other adaptation has; Atwood herself even stated that the realness of Miller’s story was too horrific to watch at times. It draws inspiration from different historical avenues: Lebensborn (a Nazi program that encouraged higher birth rates), America’s Puritan roots, and East Germany/The Iron Curtain, to name a few. The greatest accomplishment of Miller’s show is that it’s a feminist driven shock value, meant to prevent us from making the increasing anguish throughout the world our new normal. The Handmaid’s Tale is set in the Republic of Gilead, which was formerly the United States. The world is plagued with environmental disasters, as well as low fertility and birth rates. A religious extremist group took it upon themselves to make America great again; They made it look like their actions to abolish the government were the acts of Islamic terrorist groups. Once the religious extremists gained power, they forcibly separated fertile women from their families to create reproductive slaves or forced surrogates or ‘handmaids’. These handmaids are captives in the houses of a specific commander and his wife, who cannot bear children. Once a month, these women are held down and raped during ‘The Ceremony’. It was either this or exile to the Colonies, where these women would spend the rest of their lives cleaning up nuclear waste from the waging war.

Moss leads the cast as the protagonist, Offred, a feisty feminist trapped as a handmaid in a society where a single toe out of line could end her life. She can’t let that happen though. She has to stay alive so that she can find her daughter, Hannah, who was taken from her. Moss’s narration gives us an insight to all Offred’s snarky thoughts. Many people tend to find voice-over narration an example of lazy writing, or unnecessary exposition. But for a character who is allowed to speak very little (mostly in repeated phrases) the voice-over is a welcomed device.

We get to know Offred quite well throughout the show: not just through the narration of her thoughts, but also through flashbacks to her life before, with her family. These flashbacks allow the audience to piece together how not just Offred ended up in Gilead but also how little changes led to America becoming Gilead. . We see her and her colleagues being escorted out of the office because women can’t earn an income anymore. She can’t withdraw from an ATM or even use her debit card to pay for coffee. Flashbacks also tend to be an annoying narrative. But in this case, they work in favor of the story rather than against it.

It is not the flashbacks, narration, or dialogue, that shows off Moss’s spectacular acting. Rather, it’s the silence in between, the expressions on her face, the defiance that shows in Offred’s eyes as she is being slapped or tazed or whipped. Moss does have some of her work cut out for her because Offred is a brilliantly written character. I mean, what kind of person cracks jokes while looking at the dead bodies hanging above her? But Moss’s choice to play the character with astonishing nonchalance is audacious and sensational; her performance carries the show. You can’t have a well written protagonist without an equally enthralling villain. Or in this case, villains. We can say that the obvious villain is the patriarchy, or the system that designed the role of handmaids in the first place. But these are just ideas, mentalities. The Handmaid’s Tale is less about the patriarchy itself and more about the women who uphold it.

Acting alongside Moss is Yvonne Strahovski (Chuck) as Mrs. Waterford and Ann Dowd (Compliance) as Aunt Lydia, the tormenting handmaid handler. Neither of them are inherently evil. They believe that what they are doing is for the greater good of Gilead. What makes them great villains is the fact that they aren’t far off figures, like ‘Big Brother’, or whimsical in their villainy like Captain Hook. They’re written well because they’re so real, so raw. Mrs. Waterford helped create Gilead because she believes in love and in family. All she wants more than anything is a child. Aunt Lydia, though harsh and unwavering in her punishments, truly cares for the handmaids, ‘her girls’. She is a twisted motherlike figure; she punishes but only to ready the handmaids for their divine purpose. Miller has effectively created villains that you will love to hate.

Although the show has many strong points, there are many people that argue that it’s distastefully explicit. Even if you know it’s coming, there’s something new and unnerving about watching Offred lay on the lap of Mrs. Waterford while she is being raped by the Commander. We see the handmaids casually observe the bodies of hanging men, marked by their crimes: Catholic, gay, abortion clinic worker. There is a woman who is repeatedly shamed until she believes that it was her fault that she was gang-raped. These scenes don’t show everything, but they show enough. Margaret Atwood herself said that there were a few times where she had to avert her eyes because it was a scene was so horrific. The show tells a fantastic story but the violence show on screen is what’s preventing a wider audience from tuning in. it’s not a show for the faint of heart.

The show would be unwatchable if it was all doom and gloom; American Horror Story being the example that springs to mind. But, it isn’t. Just like in every story of oppression, there is resistance. There is a spark, hope, that crackles in the darkness. Many of the handmaids come together in resistance, the taste of freedom on the tip of their tongues. In our society, women resist by speaking up: they post on social media, they petition, they protest, and they march. They make themselves known, because how else will they make change happen?. But in Gilead, resistance is a quiet whisper that is carried on the wind: Mayday. Hope. Freedom. Reunion. It is human nature to resist oppression, and the Handmaid’s Tale provides a splendid exhibition of that fact.

The most horrific part of this show does not lie in its explicit nature.. It’s the extreme similarities to the reality that we live in, even though the story is based off of events that happened 30+ years ago. Moss herself thinks that using the violent nature of the show as a reason not to watch it is a weak excuse. She said, “I hate hearing that someone couldn’t watch it because it was too scary[…] I’m like, ‘Really? You don’t have the balls to watch a TV show? This is happening in your real life. Wake up, people. Wake up.’” The show’s timely premiere, close in hand with Trump’s inauguration seems coincidental. Was it? Either way, women have started dressing up in the iconic red robes and white bonnets worn by the handmaids when attending various women’s rights marches. Trump’s new policies, especially those in favor of anti-abortion, are being perceived as threatening to women. Discrimination against working mothers and women who choose not to be mothers are still battles that women continue to fight.

This ‘Handmaid’s Tale’ wasn’t written to be some urgent prophecy, but still as a potential warning of what might come to past. Aunt Lydia, a strong believer in the ‘greater good’ said it best: “Things may not seem ordinary to you right now. But they will.” It’s a dictation of the process that humans go through when they start to numb themselves towards the harrowing atrocities happening around the world, to the point where it’s becoming normal. It’s only when we look back on ‘the good ole days’ will we realize that it’s too late.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Future of American Power

Arundhati Roy on America’s Fiery, Brutal Impotence

The US leaves Afghanistan humiliated, but now faces bigger worries, from social polarisation to environmental collapse, says a novelist and essayist

— September 3rd, 2021

— By Arundhati Roy

This By-invitation commentary is part of a series by a range of global thinkers on the future of American power, examining the forces shaping the country's standing.

IN FEBRUARY 1989 the last Soviet tank rolled out of Afghanistan, its army having been decisively defeated in a punishing, nearly decade-long war by a loose coalition of mujahideen (who were trained, armed, funded and indoctrinated by the American and Pakistani Intelligence services). By November that year the Berlin wall had fallen and the Soviet Union began to collapse. When the cold war ended, the United States took its place at the head of a unipolar world order. In a heartbeat, radical Islam replaced communism as the most imminent threat to world peace. After the attacks of September 11th, the political world as we knew it spun on its axis. And the pivot of that axis appeared to be located somewhere in the rough mountains of Afghanistan.

For reasons of narrative symmetry if nothing else, as the US makes its ignominious exit from Afghanistan, conversations about the decline of the United States’ power, the rise of China and the implications this might have for the rest of the world have suddenly grown louder. For Europe and particularly for Britain, the economic and military might of the United States has provided a cultural continuity of sorts, effectively maintaining the status quo. To them, a new, ruthless, power waiting in the wings to take its place must be a source of deep worry.

In other parts of the world, where the status quo has brought unutterable suffering, the news from Afghanistan has been received with less dread.

The day the Taliban entered Kabul, I was up in the mountains in Tosa Maidan, a high, alpine meadow in Kashmir, which the Indian Army and Air Force used for decades to practise artillery and aerial bombing. From one edge of the meadow we could look down at the valley below us, dotted with martyrs’ graveyards where tens of thousands of Kashmiri Muslims who had been killed in Kashmir’s struggle for self-determination are buried.

In India, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), a Hindu nationalist group, came to power cunningly harnessing post-9/11 international Islamophobia, riding a bloody wave of orchestrated anti-Muslim massacres, in which thousands were murdered. It considers itself a staunch ally of the United States. The Indian security establishment is aware that the Taliban’s victory marks a structural shift in the noxious politics of the subcontinent, involving three nuclear powers: India, Pakistan and China, with Kashmir as a flashpoint. It views the victory of the Taliban, however pyrrhic, as a victory for its mortal enemy Pakistan, which has covertly supported the Taliban in its 20-year battle against the US occupation. Mainland India’s 175m-strong Muslim population, already brutalised, ghettoised, stigmatised as “Pakistanis”—and now, increasingly as “Talibanis”—are at even greater risk of discrimination and persecution.

Most of the mainstream media in India, embarrassingly subservient to the BJP, consistently referred to the Taliban as a terrorist group. Many Kashmiris who have lived for decades under the guns of half a million Indian soldiers, read the news differently. Wishfully. They were looking for pinholes of light in their world of darkness and indignity.

The details, the nuts and bolts of what was actually happening were still trickling in. A few who I spoke to saw it as the victory of Islam against the most powerful army in the world. Others as a sign that no power on Earth can crush a genuine freedom struggle. They fervently believed—wanted to believe—that the Taliban had completely changed and would not return to their barbaric ways. They too saw what had happened as a tectonic shift in regional politics, which they hoped would give Kashmiris some breathing space, some possibility of dignity.

The irony was that we were having these conversations sitting on a meadow pitted with bomb craters. It was Independence Day in India and Kashmir was locked down to prevent protests. On one border the armies of India and Pakistan were in a tense face-off. On another, in nearby Ladakh, the Chinese Army had crossed the border and was camped on Indian territory. Afghanistan felt very close by.

In its scores of military expeditions to establish and secure suzerainty since the second world war, the United States has smashed through (non-white) country after country. It has unleashed militias, killed millions, toppled nascent democracies and propped up tyrants and brutal military occupations. It has deployed a modern version of British colonial rhetoric—of being, in one way or another, on a selfless, civilising mission. That’s how it was with Vietnam. And so it is with Afghanistan.

Depending on where you want to put down history’s markers, the Soviets, the American- and Pakistan-backed mujahideen, the Taliban, the Northern Alliance, the unspeakably violent and treacherous warlords and the US and NATO armed forces have boiled the very bones of the Afghan people into a blood soup. All, without exception, have committed crimes against humanity. All have contributed to creating the soil and climate for terrorist groups like al-Qaeda, ISIS and their affiliates to operate.

If honourable ‘intentions’ such as empowering women and saving them from their own families and societies are meant to be mitigating factors in military invasions, then certainly both the Soviets and the Americans can rightly claim to have raised up, educated and empowered a small section of urban Afghan women before dropping them back into a bubbling cauldron of medieval misogyny. But neither democracy nor feminism can be bombed into countries. Afghan women have fought and will continue to fight for their freedom and their dignity in their own way, in their own time.

Does the US withdrawal mark the beginning of the end of its hegemony? Is Afghanistan going to live up to that old cliché about itself—the Graveyard of Empires? Perhaps not. Notwithstanding the horror show at the Kabul airport, the debacle of withdrawal may not be as big a blow to the United States as it is being made out to be.

Much of those trillions of dollars spent in Afghanistan circulated back to the US war industry, which includes weapons manufacturers, private mercenaries, logistics and infrastructure companies and non-profit organisations. Most of the lives that were lost in the US invasion and occupation of Afghanistan (estimated to be roughly 170,000 by researchers at Brown University) were those of Afghans who, in the eyes of the invaders, obviously count for very little. Leaving aside the crocodile tears, the 2,400 American soldiers who were killed don’t count for much either.

The resurgent Taliban humiliated the United States. The Doha agreement signed by both sides in 2020 for a peaceful transfer of power is testimony to that. But the withdrawal could also reflect a hard-nosed calculation by the US government about how to better deploy money and military might in a rapidly changing world. With economies ravaged by lockdowns and the coronavirus, and as technology, big data and AI make for a new kind of warfare, holding territory may be less necessary than before. Why not leave Russia, China, Pakistan and Iran to mire themselves in the quicksand of Afghanistan—imminently facing famine, economic collapse and in all probability another civil war—and keep American forces rested, mobile and ready for a possible military conflict with China over Taiwan?

The real tragedy for the United States is not the debacle in Afghanistan, but that it was played out on live television. When it withdrew from the war it could not win in Vietnam, the home front was being ripped apart by anti-war protests, much of it fuelled by enforced conscription into the armed forces. When Martin Luther King made the connection between capitalism, racism and imperialism and spoke out against the Vietnam war, he was vilified. Mohammad Ali, who refused to be conscripted and declared himself a conscientious objector, was stripped of his boxing titles and threatened with imprisonment. Although war in Afghanistan did not arouse similar passions on American streets, many in the Black Lives Matter movement made those connections too.

In a few decades, the United States will no longer be a country with a white majority. The enslavement of black Africans and the genocide and dispossession of native Americans haunt almost every public conversation today. It is more than likely that these stories will join up with other stories of suffering and devastation caused by US wars or by US allies. Nationalism and exceptionalism are unlikely to be able to prevent that from happening. The polarisation and schisms within the United States could in time lead to a serious breakdown of public order. We’ve already seen the early signs. A very different kind of trouble looms on another front too.

For centuries America had the option of retreating into the comfort of its own geography. Plenty of land and fresh water, no hostile neighbours, oceans on either side. And now plenty of oil from fracking. But American geography is on notice. Its natural bounty can no longer sustain the “American way of life”—or war. (Nor for that matter, can China’s geography sustain the “Chinese way of life”).

Oceans are rising, coasts and coastal cities are insecure, forests are burning, the flames licking at the edges of settled civilisation, devouring whole towns as they spread. Rivers are drying up. Drought haunts lush valleys. Hurricanes and floods devastate cities. As groundwater is depleted, California is sinking. The reservoir of the iconic Hoover Dam on the Colorado River, which supplies fresh water to 40m people, is drying at an alarming rate.

If empires and their outposts need to plunder the Earth to maintain their hegemony, it doesn’t matter if the plundering is driven by American, European, Chinese or Indian capital. These are not really the conversations that we should be having. Because while we’re busy talking, the Earth is busy dying.

— Arundhati Roy is a novelist and essayist.

0 notes

Note

So then, I was thinking. I know you are skeptical of the Norks being able to aim their nuked armed missiles at us. But what if their goal isn't to just Nuke a major city or two, but pop a couple of EMP bursts across the majority of the U.S. and wreck our power grid? It would take months, if not years to restore the power, and the computers systems that would be fried would take years more to replace. That alone would result in FAR more dead and chaos than just wiping a city or two away.

“OH TEH NOEZ EEE EM PEE” is one of those intricately complex issues of national infrastructure, nuclear/electromagnetic physics, weapon design and international game theory that requires a real thorough, in-depth approach by people who know what the hell they’re talking about to untangle. Naturally this means there’s infinite space for the fear-mongering media and moronic reporters racing a deadline to pick and choose their narrative. The people downplaying the hype (the Daily Mail and Popular Mechanics, if you can believe it,) and the ones pushing the panic are only telling parts of the truth, so sadly you’re stuck with me to explain what the hell’s going on.

There’s Two Kinds of EMP

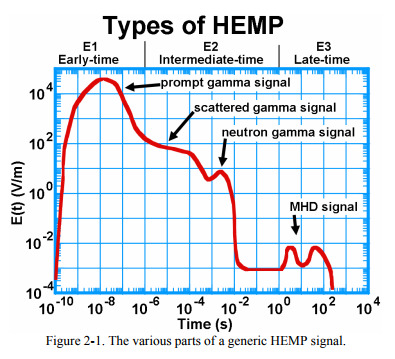

EMP produced by a nuclear blast takes two very different forms, with each one wreaking a very different kind of havoc. To understand them we need to understand how a nuclear bomb produces an EMP.

When a nuke goes off, it generates a ton of gamma rays. When these hit the atmosphere, they strip electrons from atoms in air molecules (the “Compton Effect”) which generates the electro-magnetic pulse. The initial gamma-ray burst from a nuclear weapon happens fast - one microsecond, or so - which means that the resulting EMP pulse also happens fast - and it is very energetic. This powerful and brief magnetic field induces current in conductors as it propagates outward, introducing power surges in electronics far faster than most circuitry’s clamping or surge protection devices can respond. Worse, it induces the current directly in the conductors (wires) rather than entering through a single point, like an incoming power line (which is where most surge protection is focused, for obvious reasons.) This is the EMP we usually think about - the “zap, you’re fried” kind.

But this isn’t the end of the pulse - not by a long shot:

EMP pulses are divided into three discrete phases by the scientific literature - E1, E2, and E3. Note the exponents on the “Time” axis - the initial gamma-ray pumped EMP burst takes a microsecond or so, but the E3 phase can last hundreds of seconds - possibly as long as five minutes. This is because it’s an entirely different beast.

Unlike the “E1″ EM pulse, which is triggered by the gamma rays released by the bomb, it’s the actual blast/fireball effects of the bomb going off that cause the second, much longer effects. The detonation of the bomb displaces a huge chunk of the Earth’s (now-ionized) atmosphere. When that air comes crashing back in, it creates a magetohydrodynamic effect. Magneto-hydrodynamics are infamously complex shit, but it boils down to the movement and interaction of fluid mediums having electromagnetic effects. In this case, the atmosphere is the fluid. The exact mechanisms of the effects are pretty gnarly (here’s the paper if you want to read it yourself) but the upshot is, an exo-atmospheric (high-altitude) nuclear bomb blast produces effects quite like when a Coronal Mass Ejection sends a big gob of the Sun’s atmosphere crashing into the Earth’s atmosphere - in other words, a “geomagnetic storm.” This creates an electromagnetic field of its own, but unlike the fast, violently powerful pulse of the E1, it generates radiation of much longer wavelengths, which induce current in much longer conductors - i.e. power lines. We were hit with a really powerful geomagnetic storm in 1859, which induced so much current in telegraph lines that operators unhooked their batteries to lower the current to acceptable levels.

These effects matter because they propagate quite differently, and because different bombs produce these effects in wildly different quantities. The E1 effects, the nigh-instant “pulse,” is deflected sideways when it hits the Earth’s own magnetic field - causing it to spread laterally across the Earth’s surface, and covering a lot more area than it would if it just expanded outwards as a sphere from the bomb’s detonation point. Worse, the EMP effect is generated mostly by the gamma ray output of a bomb - but most of the blast effects of a bomb come from the x-rays (which are readily absorbed by the atmosphere and produce the heat-blast shockwave that does all the damage,) so bombs are typically optimized to produce lots of x-rays. In other words, the kiloton yield of a bomb has little to do with the possible EMP effect it can have, and even a small bomb, like the 10-20 kiloton boosted fission devices the North Koreans are presumed to have, can produce a sizable EMP effect. So with just a small-yield device, the North Koreans can indeed hit a sizable part of the Continental United States (CONUS) with an E1 EMP effect caused by a high-altitude burst.

The E3 “geomagnetic storm” works - and propagates - much differently. Since it’s caused by the stirring about of the Earth’s atmosphere by a blast, the yield of a bomb is directly proportional to the strength of the E3 EMP effects. The bigger the fireball, the bigger the effect - and moreover, the lower the altitude, the bigger the effect, as it’s displacing more air... or something like that.

The consequences here are that the North Koreans cannot induce a very strong E3 effect across the entire country, as their bombs are far too low-yield to do so.

Now I’d prefer to get more in-depth and explore which kind of attack produces higher destructive field energies given a set input (i.e. a probable 20kt yield boosted fission device of the type the North Koreans likely have,) and out to what ranges, given a low-altitude versus high-altitude burst, but I don’t understand the science at play here nearly well enough to make calls on that. Furthermore, the energy threshold that determines “destructive” varies widely depending on whatever device is being affected, so making comparisons in that fashion is challenging to begin with.

The best approach, then, is to analyze what kind of damage the E1-optimized attack the North Koreans can pull off will do, as opposed to the E3-optimized attack that they cannot.

So what do they do?

Simply put, the E1 phase of an EMP tends to blow out computers and microelectronic, while the E3 phase tends to destroy the national power grid. The latter is far, far worse.

For the actual effects I’ll be relying on my two primary sources for this post; two excellent studies commissioned by the government from the clever lads at Oak Ridge Laboratories. This one concerns the E1 effects, and this one concerns the E3 effects. They used the results of actual EMP and/or power surge tests on various hardware and electronics, so we’ve some actual empirical data to work with, too.

The E1 pulse is high-powered and high-frequency, which means it affects small devices the most - the small wavelength means it can induce current effectively in relatively short conductors. The antenna in your cell phone is more than long enough, for instance. Worse, long cables (like Ethernet lines) also make these devices vulnerable, because while the high-frequency burst won’t induce current as effectively in longer conductors, the pulse is generating tens of thousands of volts - and it’s hitting computer circuits designed for a few volts. Thus Ethernet lines et al can expose any given computer to a lot more induced current than it might’ve picked up from its own internal conductors; it increases the “attack surface,” so to speak. This applies in a wider sense - small devices like wristwatches are unlikely to be affected at all, whereas a big office building’s entire computer network is likely in deep shit. As the report notes, it’s nigh impossible to model how any one electronic device - an IC, a smartphone, whatever - will fail, because they’re such complex pieces of engineering with so many tiny sub-component chips and connections in them. Empirical testing is mandatory to get even a crude idea of the vulnerability, but that requires actually generating an EMP field to try frying things with - meaning there’s no good way to actually test big devices, much less entire building-sized computer networks! This naturally makes estimating the damage from any one EMP almost impossible - and this is before we consider the possible consequences of system upsets, i.e. a temporary error introduced by scrambled 1s and 0s induced by a power surge that doesn’t actually do damage. Corrupted data on tape drives, a system that hiccups for a moment, etc. In some industrial equipment such a bug could cause actual physical damage, and in other places you might just have to reboot your computer and go on your merry way.

I’ll go off on my own, then, and point out that while all the above looks pretty grim for your average smartphone or desktop PC, that’s far from a universal truth. The E1 EMP would have to propagate just like any other field, which means the location - and even the orientation relative to the blast’s source - of the EMP would drastically effect how hard any given system or network is hit. Your average wage-slave workstation will fare poorly, but my gaming rig - built into a hulking metal Cooler Master case with enough fans that it can damn near hover - might fare better. Unless said workstation is inside a massive skyscraper office building, with tons of structural steel, piping, and power cabling helping to form a faraday cage around the entire interior space, as well as high-quality, fast-acting anti-surge protection in the basement. In fact, the city that building is in can affect the currents generated as well, either diminishing or intensifying them.

What won’t be badly affected by the E1 pulse is the nation’s electrical grid - or the nation’s cars. Cars are basically rolling faraday cages, and there’s been actual empirical testing of relatively modern cars with high reliance on internal computer micro-controllers (in 2008) that showed most of them weathered high-power EMP fairly well. There are real risks to the computer controls of our power grid, and the study is up-front about them - but the important thing is that the actual heavy-duty switching equipment tends to be far more robust, and despite ongoing modernization, a lot of it’s still very rugged electro-mechanical “dumb” systems. An E1 pulse could definitely cause serious blackouts, with results much like what we saw during the great East Coast Blackout - rioting, looting, etc. - but a concerted effort could have the damage being repaired, and power flowing again, relatively quickly.

Lots of computers will fry, but the power grid will survive, and so will our cars. The data and productivity loss (from non-operable gas stations, etc.,) will hit our economy hard, but the crucial point is that the damage to our crucial infrastructure will be limited to the most delicate parts of the control systems - in other words, highly centralized. This will make it much, much easier to repair. The potential data loss will probably be more devastating to the national economy with its impact on business, because that’s more irreparable and more permanent, depending on the scale and strength of the attack. However, some companies will come through much better than others (GO TO THE NUCLEAR CLOUD LOL TAPE BACKUPS IN THE BASEMENT 4 EVAH), the economy would rebalance and in the end, it’d be something we could weather and recover from. And remember, this is the worst-case scenario, and even the experts have spoken to how impossible it is to really quantify the potential damage from this kind of EMP. The essential point is our cars would keep rolling, our power would stay on, and the essential backbone of our civilization’s infrastructure would stay intact. No doom, no gloom, no “90% of the country dying of famine and disease,” no leather-and-metal clad post-apocalyptic biker gangs.

The E3 effects are much, much worse, however, because the lower-frequency EM radiation is much harder to shield against, and induces current quite well in our national web of high-tension power lines. Worse, it induces Direct Current, in a system that’s designed for Alternating Current. Since our national power grid is a much more limited and quantifiable system than “every computer thing in the US,” the Oak Ridge Lab was able to do a rather more comprehensive analysis of the potential damage. The long and short of it is, the induced DC currents in the power lines don’t damage control systems - they damage the transformers and switching equipment, the heavy, expensive, elaborate guts of the power network itself. As the study says, this damage could take YEARS to repair. If an attack utilizing multiple higher-yield bombs - targeted to detonate over the most crucial parts of the US power network - were to be made, it could stand a very good chance of plunging the United States into a literal and figurative dark age. Then you can talk about societal collapse and Mad Max scenarios.

In Conclusion

It’s very, very hard to impossible to properly quantify the effects of EMP bursts - even moreso because a great deal of the related research is extremely highly classified and locked away in government archives for obvious reasons. But what we can infer pretty directly is that the truly devastating kind of EMP is the E3 effects that require fairly large-yield bombs to induce to any great degree, exactly the kind of bombs the North Koreans do not have. There’s been some baseless bullshitting about the North Koreans getting their hands on “super-EMP” bomb designs, but even if they somehow got their hands on some of the Soviet Union’s most closely-kept theoretical weapons research, you have to crawl before you can run - and they’re currently laboring on perfecting simple boosted-fission devices.

However, as people have been saying for years now, all of this is only a matter of time. The North Koreans are rumored to already be working in hydrogen bombs - and those would give them the high-yield weapons needed for the truly devastating kind of EMP attack detailed above.

Currently, the only defense the CONUS has is the Ground-Based Interceptors, previously known as Ground-Based Midcourse Intercept - an ABM program funded and championed by Bush, and later cut down and hamstrung by Obama. It’s because of Bush’s foresight years ago that we have even that scant defense. We are out of time - we need to decide, now, if we’re going to invest untold billions into an expanded missile defense system that might be enough to hold off North Korea’s future attack capabilities, EMPs included - or if we need to take our last chance to end these crazy bastards now, before they end us.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

The moon is an egg. This is why that matters.

I’ve wanted to write about the Doctor Who episode where the MOON is an EGG for some time now, really more or less since it aired. When I first saw it I thought it had something quite important to say — about Doctor Who itself, but also about our culture and society — and it’s something that’s become more important in the months and years that have followed. I haven’t actually watched the episode since it aired, so I imagine I’ll make loads of mistakes about the plot and characters and structure of the thing. Hopefully that won’t matter, but if it does you can feel better by shouting at me online.

I remember the basics of the episode, at least. In Kill the Moon, the Doctor, his companion and a little girl travel to the moon in 2049. There, they discover that unusual tidal activity caused by the moon has become a threat to humanity, and a group of astronauts has come to destroy the satellite with nuclear bombs. However, it turns out that changes to the moon’s behaviour have come about because — improbably — it’s really an enormous alien egg which is in the process of hatching. At the end of the episode the moon shatters apart as a giant, dragon-like alien emerges from it, an alien who — the Doctor says — will fascinate humanity so much that they feel they’ll have to go out and explore the universe again.

Below the surface, however, I thought Kill the Moon was about something else entirely. After the episode had first aired, I heard that people on the Doctor Who discussion forums had wondered if the moon from the 1967 serial The Moonbase was an egg too, and asked why no-one had ever thought to mention this at the time. This, I thought, is almost exactly the wrong question to ask about Kill the Moon, because the whole point of the thing is that the moon of 2014 is not the same as the moon of 1967. In the sixties, the idea that human civilisation would one day expand out to space was more or less taken as read: bases on the moon and inhabited wheels in space were things that could quite conceivably exist in the real future as well as the one the Doctor poked around in on-screen. Against this backdrop, the race to put a man on the moon is symbolic of a wider assumed future — and one which adults and children could both conceivably believe in.

Subtextually, I think Kill the Moon is about what happens when this future no longer seems real. In it, the weapons of the sixties — the Earth’s last ever nuclear bombs — are intended to destroy the imagined future of the sixties, here represented by the moon itself. Significantly, the episode portrays the moon as being a bit rubbish; grey, breaking apart, literally covered in cobwebs, coded as something from our past instead of our future. It’s there as the spent remains of what the future was going to be rather than what any of us now think the future really is, and there to remind us that the symbols of that future are not ones that hold real power or appeal for our society anymore.

This, the episode has realised, presents something of a problem for Doctor Who. As a cultural artefact that is itself from the sixties, the future as a place where human expansion and exploration beyond Earth is something that actually happens is more or less hard-coded into the show’s DNA. However, Who has now been around for long enough that the future depicted in its earlier years is either already close to becoming the past — the 1967 serial TheEnemy of the World, for example, is set in the distant era of 2018 — or is manifestly not going to become a reality in the years to come. Half the men who walked on the moon are now dead; it’s 45 years since a human set foot on the place. The expansion that seemed inevitable in the sixties has dissipated away, and the symbology of the future has stayed the same more or less through sheer inertia.

Kill the Moon, then, alludes to the simple fact that this state of affairs cannot continue. Post the 2008 financial crisis, it seems like the future is a place where we all work longer hours for less money in increasingly precarious ways, which isn’t really a recipe for an exciting series of adventures in space and time. This view of the future hasn’t changed since Kill the Moon aired in 2014. Indeed, if anything the future it portrays now seems over-optimistic: it seems rather less likely in 2017 that our future will contain global nuclear disarmament and a black, female president of the USA. Given this, what can a show whose stock in trade is showing us our future actually do? How can it find a way to be optimistic about what lies ahead, at a time where this seems to be ignoring the facts of reality?

Well, it can do it by changing the facts of reality. Apparently, a lot of people criticised Kill the Moon after it aired because most of the things that happen in it are very unscientific. That’s true, but I’m not sure it matters — it’s a text about the way we conceive of the things that exist in the world, rather than one about what those things might or might not actually be. The episode says, in effect, that the future can only be reconceptualised — and by extension, can only be saved — if our perception of the universe changes in a radical way. It’s not enough to continue on with the same tropes around what the future is or what it means. Rather, we need to be able to inhabit a world radically different from the present in basic ways — such as coming to think of the moon as an egg, and the future as a place inhabited by fantastical dragons.

It all falls down, of course, when you ask what this radical new way of viewing things actually is. Here in the UK, I remember in 2015’s Labour leadership contest Yvette Cooper ran on a platform of saying young people needed to be engaged in politics in ways that were quite different to the ones stuffy old people were doing at the time. This is probably true, but an old woman at one of the party’s hustings punctured things by asking what these new ways of engagement might look like, exactly. I think the simple answer is that most of us don’t know, and in the end, I don’t think Kill the Moon does, either — it asks the question “what, exactly, should the underlying narrative be for an optimistic view of the 21st century?”, then tries to convince us that the answer is “taking inspiration from a CGI dragon.” That’s not to say it isn’t saying worthwhile things — contrary to some, I think it’s fine and valid to articulate a problem you yourself have no solution to — but to say that it defines a new space for science fiction to be in rather than doing much within that space itself.

In 2017, however, I think we might be closer to articulating an answer. Just as it was impossible that a dragon could hatch from an egg, it was impossible for Donald Trump to become the president of the United States. Now that the second of these impossibilities is our reality, it’s worth thinking about how this was able to happen, and how some of the forces that enabled it could be used to bring about rather more positive changes. In the days after Trump’s inauguration, I found myself thinking about how those of us who were against him had reacted to his proposals to build “The Wall” — an unbroken barrier stretching over 2000 miles intended to close the border between Mexico and the USA. The Wall, we said, was a patently ridiculous idea, and in many ways it still is. But while I think we were correct to criticise the attitudes that would lead to The Wall being seen as desirable, I now think we were wrong to criticise the ambition. Just as we now don’t send people to the moon or expect ourselves to ever travel to outer space, we’ve come to believe that a public infrastructure project on The Wall’s scale just isn’t something people do anymore. Yet this science fiction is becoming reality: The Wall will be built, and the impossibilities that need to be put into place will become possibilities.

I think this sort of place is perhaps where hope of a kind can be gleaned. The dying future criticised in Kill the Moon is now surely dead; our immediate future is one of a fractured humanity on a single planet, not a united species headed towards the stars. In many ways, to me it’s the stuff of nightmares — the only comfort I can think of is that nightmares are built of the same material of dreams, and that in the sheer scale of what lies ahead we may allow ourselves to think in truly radical ways again. If we can actually achieve tasks like the construction of thousand-mile barriers and the negotiation of leaving the European Union, it surely follows that we can achieve things that match their ambition while rejecting their intent. And I think telling stories about that is crucial, too, because we need to set out visions of what our future can look like that draw from the stories and experiences of our lived present, and not from the desiccated husks of an aesthetic over half a century old. Real originality in fiction is needed to forge a reality that’s better than this one — I think that was the message of Kill the Moon, when boiled down to its basic form. Act and create, it says, and do it now– because we live in a world where the moon can be an egg, and we live in a world where the future can be saved.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The New Age of Astrology

Astrology is a meme and it’s spreading in that blooming, unfurling way that memes do. On social media, astrologers and astrology meme machines amass tens or hundreds of thousands of followers, people joke about Mercury retrograde, and categorize “the signs as…” literally anything: cat breeds, Oscar Wilde quotes, Stranger Things characters, types of French fries. In online publications, daily, weekly, and monthly horoscopes, and zodiac-themed listicles flourish.

This isn’t the first moment astrology’s had and it won’t be the last. The practice has been around in various forms for thousands of years. More recently, the New Age movement of the 1960s and ‘70s came with a heaping helping of the Zodiac. (Some also refer to the New Age as the “Age of Aquarius”—the two-thousand-year period after the Earth is said to move into the Aquarius sign.)

In the decades between the New Age boom and now, while astrology certainly didn’t go away—you could still regularly find horoscopes in the back pages of magazines—it “went back to being a little bit more in the background,” says Chani Nicholas, an astrologer based in Los Angeles. “Then there’s something that’s happened in the last five years that’s given it an edginess, a relevance for this time and place, that it hasn’t had for a good 35 years. Millennials have taken it and run with it.”

Many people I spoke to for this piece said they had a sense that the stigma attached to astrology, while it still exists, had receded as the practice has grabbed a foothold in online culture, especially for young people.

“Over the past two years, we’ve really seen a reframing of New Age practices, very much geared towards a Millennial and young Gen X quotient,” says Lucie Greene, the worldwide director of J. Walter Thompson’s innovation group, which tracks and predicts cultural trends.

Callie Beusman, a senior editor at Broadly says traffic for the site’s horoscopes “has grown really exponentially.” Stella Bugbee, the president and editor-in-chief of The Cut, says a typical horoscope post on the site got 150 percent more traffic in 2017 than the year before.

In some ways, astrology is perfectly suited for the internet age. There’s a low barrier to entry, and nearly endless depths to plumb if you feel like falling down a Google research hole. The availability of more in-depth information online has given this cultural wave of astrology a certain erudition—more jokes about Saturn returns, less “Hey baby, what’s your sign?” pickup lines.

A quick primer: Astrology is not a science; there’s no evidence that one’s Zodiac sign actually correlates to personality. But the system has its own sort of logic. Astrology ascribes meaning to the placement of the sun, the moon, and the planets within 12 sections of the sky—the signs of the Zodiac. You likely know your sun sign, the most famous Zodiac sign, even if you’re not an astrology buff. It’s based on where the sun was on your birthday. But the placement of the moon and each of the other planets at the time and location of your birth adds additional shades to the picture of you painted by your “birth chart.”

What horoscopes are supposed to do is give you information about what the planets are doing right now, and in the future, and how all that affects each sign. “Think of the planets as a cocktail party,” explains Susan Miller, the popular astrologer who founded the AstrologyZone website. “You might have three people talking together, two may be over in the corner arguing, Venus and Mars may be kissing each other. I have to make sense of those conversations that are happening each month for you.”

“Astrologers are always trying to boil down these giant concepts into digestible pieces of knowledge,” says Nicholas. “The kids these days and their memes are like the perfect context for astrology.”

Astrology expresses complex ideas about personality, life cycles, and relationship patterns through the shorthand of the planets and Zodiac symbols. And that shorthand works well online, where symbols and shorthand are often baked into communication.

“Let me state first that I consider astrology a cultural or psychological phenomenon,” not a scientific one, Bertram Malle, a social cognitive scientist at Brown University told me in an email. But “full-fledged astrology”—that goes beyond newspaper style sun sign horoscopes—“provides a powerful vocabulary to capture not only personality and temperament but also life’s challenges and opportunities. To the extent that one simply learns this vocabulary, it may be appealing as a rich way of representing (not explaining or predicting) human experiences and life events, and identifying some possible paths of coping.”

People tend to turn to astrology in times of stress. A small 1982 study by the psychologist Graham Tyson found that “people who consult astrologers” did so in response to stressors in their lives—particularly stress “linked to the individual’s social roles and to his or her relationships,” Tyson wrote. “Under conditions of high stress, the individual is prepared to use astrology as a coping device even though under low stress conditions he does not believe in it.”

According to American Psychological Association survey data, since 2014, Millennials have been the most stressed generation, and also the generation most likely to say their stress has increased in the past year since 2010. Millennials and Gen X-ers have been significantly more stressed than older generations since 2012. And Americans as a whole have seen increased stress because of the political tumult since the 2016 presidential election. The 2017 edition of the APA’s survey found that 63 percent of Americans said they were significantly stressed about their country’s future. Fifty-six percent of people said reading the news stresses them out, and Millennials and Gen X-ers were significantly more likely than older people to say so. Lately that news often deals with political infighting, climate change, global crises, and the threat of nuclear war. If stress makes astrology look shinier, it’s not surprising that more seem to be drawn to it now.

Nicholas’s horoscopes are evidence of this. She has around one million monthly readers online, and recently snagged a book deal—one of four new mainstream astrology guidebooks sold in a two-month period in summer 2017, according to Publisher’s Marketplace. Anna Paustenbach, Nicholas’s editor at HarperOne, told me in an email that Nicholas is “at the helm of a resurgence of astrology.” She thinks this is partly because Nicholas’s horoscopes are explicitly political. On September 6, the day after the Trump administration announced it was rescinding DACA—the deferred action protection program for undocumented immigrants—Nicholas sent out her typical newsletter for the upcoming full moon. It read, in part:

The full moon in Pisces…may open the flood gates of our feelings. May help us to empathize with others… May we use this full moon to continue to dream up, and actively work towards, creating a world where white supremacy has been abolished.

Astrology offers those in crisis the comfort of imagining a better future, a tangible reminder of that clichéd truism that is nonetheless hard to remember when you’re in the thick of it: This too shall pass.

In 2013, when Sandhya was 32 years old, she downloaded the AstrologyZone app, looking for a road map. She felt lonely, and unappreciated at her nonprofit job in Washington D.C., and she was going out drinking four or five times a week. “I was in the cycle of constantly being out, trying to escape,” she says.

She wanted to know when things would get better and AstrologyZone had an answer. Jupiter, “the planet of good fortune,” would move into Sandhya’s zodiac sign, Leo, in one year’s time, and remain there for a year. Sandhya remembers reading that if she cut clutter out of her life now, she’d reap the rewards when Jupiter arrived.

So Sandhya spent the next year making room for Jupiter. (She requested that we not publish her last name because she works as an attorney and doesn’t want her clients to know the details of her personal life.) She started staying home more often, cooking for herself, applying for jobs, and going on more dates. “I definitely distanced myself from two or three friends who I didn’t feel had good energy when I hung around them,” she says. “And that helped significantly.”

Jupiter entered Leo on July 16, 2014. That same July, Sandhya was offered a new job. That December, Sandhya met the man she would go on to marry. “My life changed dramatically,” she says. “Part of it is that a belief in something makes it happen. But I followed what the app was saying. So I credit some of it to this Jupiter belief.”

Humans are narrative creatures, constantly explaining their lives and selves by weaving together the past, present, and future (in the form of goals and expectations). Monisha Pasupathi, a developmental psychologist who studies narrative at the University of Utah, says that while she lends no credence to astrology, it “provides [people] a very clear frame for that explanation.”

It does give one a pleasing orderly sort of feeling, not unlike alphabetizing a library, to take life’s random events and emotions and slot them in to helpfully labeled shelves. This guy isn’t texting me back because Mercury retrograde probably kept him from getting the message. I take such a long time to make decisions because my Mars is in Taurus. My boss will finally recognize all my hard work when Jupiter enters my 10th house. A combination of stress and uncertainty about the future is an ailment for which astrology can seem like the perfect balm.

Sandhya says she turns to astrology looking for help in times of despair, “when I’m like ‘Someone tell me the future is gonna be okay.’” Reading her horoscope was like flipping ahead in her own story.

“I’m always a worrier,” she says. “I’m one of those people who, once I start getting into a book, I skip ahead and I read the end. I don’t like cliffhangers, I don’t like suspense. I just need to know what’s gonna happen. I have a story in my head. I was just hoping certain things would happen in my life, and I wanted to see if I am lucky enough for them to happen.”

Now that they have happened, “I haven’t been reading [my horoscope] as much,” she says, “and I think it’s because I’m in a happy place right now.”

Maura Dwyer

For some, astrology’s predictions function like Dumbo’s feather—a comforting magic to hold onto until you realize you could fly on your own all along. But it’s the ineffable mystical sparkle of the feather—gentler and less draining than the glow of a screen— that makes people reach for it in the first place.

People are starting to get sick of a life lived so intensely on the grid. They wish for more anonymity online. They’re experiencing fatigue with e-books, with dating apps, with social media. They’re craving something else in this era of quantified selves, and tracked locations, and indexed answers to every possible question. Except, perhaps the questions of who you really are, and what life has in store for you

Ruby Warrington is a lifestyle writer whose New Age guidebook Material Girl, Mystical World came out in May 2017—just ahead of the wave of astrology book sales this summer. She also runs a mystical esoterica website, The Numinous, a word which Merriam-Webster defines as meaning “supernatural or mysterious,” but which Warrington defines on her website as “that which is unknown, or unknowable.”

“I think that almost as a counterbalance to the fact that we live in such a quantifiable and meticulously organized world, there is a desire to connect to and tap into that numinous part of ourselves,” Warrington says. “I see astrology as a language of symbols that describes those parts of the human experience that we don't necessarily have equations and numbers and explanations for.”

J. Walter Thompson’s Intelligence Group released a trend report in 2016 called “Unreality” that says much the same thing: “We are increasingly turning to unreality as a form of escape and a way to search for other kinds of freedom, truth and meaning,” it reads. “What emerges is an appreciation for magic and spirituality, the knowingly unreal, and the intangible aspects of our lives that defy big data and the ultratransparency of the web.” This sort of reactionary cultural 180 has happened before—after The Enlightenment’s emphasis on rationality and the scientific method in the 17th and 18th centuries, the Romantic movement found people turning toward intuition, nature, and the supernatural. It seems we may be at a similar turning point. New York magazine even used the seminal Romantic painting Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog to illustrate Andrew Sullivan’s recent anti-technology essay, “I Used to Be a Human Being.”

JWT and another trend forecasting group, WGSN, in its report “Millennials: New Spirituality” lump astrology in with other New Age mystical trends that have caught on with young people in recent years: healing crystals, sound baths, and tarot, among others.

“I think it’s become generally less acceptable to just arbitrarily shit on things as like “that’s not rational, or that’s stupid because that’s not fact,” says Nicole Leffel, a 28-year-old software engineer who lives in New York.

Bugbee, the editor-in-chief of The Cut, noticed this shift a couple years ago. “I could just tell that people were sick of a certain kind of snarky tone,” she said. Up to that point, the site had been running slightly irreverent horoscopes with gifs meant to encapsulate the week’s mood for each sign. But Bugbee realized “that people wanted sincerity more than anything. So we just kind of went full sincere with [the horoscopes], and that’s when we saw real interest happen.”

But a sincere burgeoning interest in astrology doesn’t mean people are wholesale abandoning rationality for more mystical beliefs. Nicholas Campion, a historian of astrology points out that the question of whether people “believe” in astrology is both impossible to answer, and not really a useful question to ask. People might say they don’t “believe” in astrology, but still identify with their Zodiac sign. They may like to read their horoscope, but don’t change their behavior based on what it says. There is more nuance than this statistic allows for.

Many mainstream examinations of astrology as a trend are deeply concerned with debunking. They like to trot out the National Science Foundation survey that measures whether people think astrology is scientific, and remind readers that it’s not. Which, it’s not. But that’s not really the point.

While there are surely some people who blindly accept astrology as fact and view it as on par with a discipline like biology, that doesn’t seem to be the case among many of the young adults who are fueling this renaissance of the Zodiac. The people I spoke to for this piece often referred to astrology as a tool, or a kind of language—one that, for many, is more metaphorical than literal.

“Astrology is a system that looks at cycles, and we use the language of planets,” says Alec Verkuilen Brogan, a 29-year-old chiropractic student based in the Bay Area who has also studied astrology for 10 years. “It's not like these planets are literally going around and being like ‘Now, I'm going to do this.’ It’s a language to speak to the seasons of life.”

Michael Stevens, a 27-year-old who lives in Brooklyn, was in the quarter-life crisis season of life around the time of the total solar eclipse in August this year. “Traditionally, I’m a skeptic,” he says. “I’m a hardcore, like Dana Scully from X-Files type of person. And then shit started to happen in life.” Around the time of the eclipse, in the course of his advertising work, he cold-called Susan Miller of AstrologyZone, to ask if she would put some ads on her site.

She was annoyed, he says, that he called her at the end of the month, which is when she writes her famously lengthy horoscopes. But then she asked him for his sign—Sagittarius. “And she’s like, ‘Oh, okay, this new moon’s rough for you.’” They talked about work and relationship troubles. (Miller doesn’t remember having this conversation specifically, but says “I’m always nice to the people who cold-call. It sounds totally like me.”)

Studies have shown that if you write a generic personality description and tell someone it applies to them, they’re likely to perceive it as accurate—whether that’s in the form of a description of their Zodiac sign or something else.

Stevens says he could’ve potentially read into his conversation with Miller in this way. “She’s like ‘You’re going through a lot right now,’” he says. “Who isn’t? It’s 2017. ”

Still, he says the conversation made him feel better; it spurred him to take action. In the months between his call with Miller and our conversation in October, Stevens left his advertising job and found a new one in staffing. Shortly before we spoke, he and his girlfriend broke up.

“[I realized] I’m acting like a shitty, non-playable character in a Dungeons and Dragons RPG,” Stevens says, “so I should probably make choices, and pursue some of the good things that could happen if I just [cared] about being a happy person in a real way.”

Stevens’ story exemplifies a prevailing attitude among many of the people I talked to—that it doesn’t matter if astrology is real; it matters if it’s useful.

“We take astrology very seriously, but we also don't necessarily believe in it,” says Annabel Gat, the staff astrologer at Broadly, “because it's a tool for self-reflection, it's not a religion or a science. It’s just a way to look at the world and a way to think about things.”

Beusman, who hired Gat at Broadly, shares her philosophy. “I believe several conflicting things in all areas of my life,” she says. “So for me it's very easy to hold these two ideas in my head at once. This could not be true at all, and also, I'll be like ‘Well, I have three planets entering Scorpio next month, so I should make some savvy career decisions.’”

This attitude is exemplified by The Hairpin’s “Astrology Is Fake” column, by Rosa Lyster, with headlines like “Astrology Is Fake But Leos Are Famous,” and “Astrology Is Fake But Taurus Hates Change.”

It might be that Millennials are more comfortable living in the borderlands between skepticism and belief because they’ve spent so much of their lives online, in another space that is real and unreal at the same time. That so many people find astrology meaningful is a reminder that something doesn’t have to be real to feel true. Don’t we find truth in fiction?

In describing her attitude toward astrology, Leffel recalled a line from Neil Gaiman’s American Gods in which the main character, Shadow, wonders whether lightning in the sky was from a magical thunderbird, “or just an atmospheric discharge, or whether the two ideas were, on some level, the same thing. And of course they were. That was the point after all.”

If the “astrology is fake but it’s true” stance seems paradoxical, well, perhaps the paradox is what’s attractive. Many people offered me hypotheses to explain astrology’s resurgence. Digital natives are narcissistic, some suggested, and astrology is a navel-gazing obsession. People feel powerless here on Earth, others said, so they’re turning to the stars. Of course, it’s both. Some found it to be an escape from logical “left-brain” thinking; others craved the order and organization the complex system brought to the chaos of life. It’s both. That’s the point, after all.

To understand astrology’s appeal is to get comfortable with paradoxes. It feels simultaneously cosmic and personal; spiritual and logical; ineffable and concrete; real and unreal. It can be a relief, in a time of division, not to have to choose. It can be freeing, in a time that values black and white, ones and zeroes, to look for answers in the grey. It can be meaningful to draw lines in the space between moments of time, or the space between pinpricks of light in the night sky, even if you know deep down they’re really light-years apart, and have no connection at all.

from Health News And Updates https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2018/01/the-new-age-of-astrology/550034/?utm_source=feed

0 notes

Link

COLD WAR 2.0. Although the evidence for Russia’s interference appears convincing, it is too easy to allow such an account to become the master narrative of Trump’s ascent—a way to explain the presence of a man who is so alien and discomforting to so much of the population by rendering him in some way foreign. In truth, he is a phenomenon of America’s own making. At the same time, Trump’s management style as President has been so chaotic, so improvisational, that the daily bonfire sometimes obscures what has been put in place. “Putin likes people like Tillerson, who do business and don’t talk about human rights,” one former Russian policy adviser said. The Trump Administration, notably, said nothing when a Russian court—the courts are well within Putin’s control—found Alexei Navalny, an anti-corruption campaigner and Putin’s only serious rival in next year’s Presidential election, guilty of a fraud charge that had already been overturned once, a conviction that may keep him out of the race. The Russians see friendly faces in the Administration. Tillerson, as the chairman of ExxonMobil, did “massive deals in Russia,” as Trump has put it. He formed an especially close relationship with Igor Sechin, who is among Putin’s closest advisers, and who has made a fortune as chief executive of the state oil consortium, Rosneft. Trump’s first national-security adviser, Michael Flynn, took a forty-thousand-dollar fee from the Russian propaganda station RT to appear at one of its dinners, where he sat next to Putin. The Obama Administration, in its final days, had retaliated against Russian hacking by expelling thirty-five Russian officials and closing two diplomatic compounds. The Kremlin promised “reciprocal” punishment, and American intelligence took the first steps in sending new officials to Moscow to replace whoever would be expelled. “People were already on planes,” a U.S. intelligence official said. But on December 30th Putin said that he would not retaliate. To understand the abrupt reversal, American intelligence scrutinized communications involving Sergey Kislyak, Russia’s Ambassador to the U.S., and discovered that Flynn had had conversations with him, which touched on the future of economic sanctions. (Jared Kushner, Trump’s son-in-law, met with Kislyak in Trump Tower during the transition; the aim, according to the White House, was to establish “a more open line of communication in the future.”) Flynn was forced to resign when news broke that he had lied to Vice-President Mike Pence about these exchanges. Trump has given risibly inconsistent accounts of his own ties to Russia. When he was in Moscow for the Miss Universe contest in 2013, and an interviewer for MSNBC asked him about Putin, he said, “I do have a relationship and I can tell you that he’s very interested in what we’re doing here today”; at a subsequent National Press Club luncheon, he recalled, “I spoke indirectly and directly with President Putin, who could not have been nicer.” During the Presidential campaign, he said, “I never met Putin, I don’t know who Putin is.” Trump has tweeted that he has “nothing to do with Russia”; in 2008, his son Donald, Jr., said that “Russians make up a pretty disproportionate cross-section of a lot of our assets.” At a news conference on February 16th, Trump was asked, again, if anyone in his campaign had been in contact with Russia, and he said, “Nobody that I know of.” He called reports of Russian contacts “a ruse,” and said, “I have nothing to do with Russia. Haven’t made a phone call to Russia in years. Don’t speak to people from Russia.” The next day, the Senate Intelligence Committee formally advised the White House to preserve all material that might shed light on contacts with Russian representatives; any effort to obscure those contacts could qualify as a crime. By mid-February, law-enforcement and intelligence agencies had accumulated multiple examples of contacts between Russians and Trump’s associates, according to three current and former U.S. officials. Intercepted communications among Russian intelligence figures are said to include frequent reference to Paul Manafort, Trump’s campaign chairman for several months in 2016, who had previously worked as a political consultant in Ukraine. “Whether he knew it or not, Manafort was around Russian intelligence all the time,” one of the officials said. Investigators are likely to examine Trump and a range of his associates—Manafort; Flynn; Stone; a foreign policy adviser, Carter Page; the lawyer Michael Cohen—for potential illegal or unethical entanglements with Russian government or business representatives. “To me, the question might finally come down to this,” Celeste Wallander, President Obama’s senior adviser on Russia, said. “Will Putin expose the failings of American democracy or will he inadvertently expose the strength of American democracy?” The working theory among intelligence officials involved in the case is that the Russian approach—including hacking, propaganda, and contacts with Trump associates—was an improvisation rather than a long-standing plan. The official said, “After the election, there were a lot of Embassy communications”—to Moscow—“saying, stunned, ‘What we do now?’ ” Initially, members of the Russian élite celebrated Clinton’s disappearance from the scene, and the new drift toward an America First populism that would leave Russia alone. The fall of Michael Flynn and the prospect of congressional hearings, though, have tempered the enthusiasm. Fyodor Lukyanov, the editor-in-chief of a leading foreign-policy journal in Moscow, said that Trump, facing pressure from congressional investigations, the press, and the intelligence agencies, might now have to be a far more “ordinary Republican President than was initially thought.” In other words, Trump might conclude that he no longer has the political latitude to end sanctions against Moscow and accommodate Russia’s geopolitical ambitions. As a sign of the shifting mood in Moscow, the Kremlin ordered Russian television outlets to be more reserved in their coverage of the new President. Konstantin von Eggert, a political commentator and host on Russian television, heard from a friend at a state-owned media holding that an edict had arrived that, he said, “boiled down to one phrase: no more Trump.” The implicit message, von Eggert explained, “is not that there now should be negative coverage but that there should be much less, and more balanced.” The Kremlin has apparently decided, he said, that Russian state media risked looking “overly fawning in their attitude to Trump, that all this toasting and champagne drinking made us look silly, and so let’s forget about Trump for some time, lowering expectations as necessary, and then reinvent his image according to new realities.” Alexey Venediktov, the editor-in-chief of Echo of Moscow, and a figure with deep contacts inside the Russian political élite, said, “Trump was attractive to people in Russia’s political establishment as a disturber of the peace for their counterparts in the American political establishment.” Venediktov suggested that, for Putin and those closest to him, any support that the Russian state provided to Trump’s candidacy was a move in a long-standing rivalry with the West; in Putin’s eyes, it is Russia’s most pressing strategic concern, one that predates Trump and will outlast him. Putin’s Russia has to come up with ways to make up for its economic and geopolitical weakness; its traditional levers of influence are limited, and, were it not for a formidable nuclear arsenal, it’s unclear how important a world power it would be. “So, well then, we have to create turbulence inside America itself,” Venediktov said. “A country that is beset by turbulence closes up on itself—and Russia’s hands are freed.”

0 notes