#couthon

Text

I am geographically challenged, and I really, really wanted a way to visualise what constituencies the members of the Third Committee of Public Safety ( July 1793 – July 1794) represented. So, this map was born.

Bertrand Barère: Hautes-Pyrénées

Jacques Billaud-Varenne: Paris

Lazare Carnot: Pas-de-Calais

Jean-Marie Collot: Paris

Georges Couthon: Puy-de-Dôme

Marie-Jean Hérault de Séchelles: Seine-et-Oise

Robert Lindet: Eure

Pierre-Louis Prieur de la Marne: Marne (hence the name…)

Claude-Antoine Prieur: Côte-d'Or (ditto)

Maximilien Robespierre: Paris

André Jeanbon Saint-André: Lot

Louis Antoine de Saint-Just: Aisne

PS: It’s fascinating and telling how many of them represented provinces in the north of France.

#frev#robespierre#french revolution#couthon#barere#collot#billaud varenne#herault#lazare carnot#saint just#saint-andre#Committee of Public Safety#priuer

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

✨Happy New Year 2024 everyone (a little bit late however)✨

#frev#french revolution#digital art#18th century art#black and white#frev art#saint just#robespierre#bonbon#lebas#couthon#barère#happy new year#new year 2024

210 notes

·

View notes

Text

176 notes

·

View notes

Text

I found the Charlotte Robespierre-pins-down-Couthon-in-an-armchair-and-calls-him-a-hypocrite anecdote in its full glory within La Révolution, la Terreur, le Directoire 1791-1799: d’après les mémoires de Gaillard (1908) page 263-272. The table of contents claim this event happened in May 1794.

-

Gaillard therefore presents himself at Mlle Robespierre's house, she welcomes him in a friendly manner, she does not seek to know the political opinions of her visitor; both talk for a long time about her family and their old acquaintances, she names for Gaillard, with great bitterness, the prodigious number of very honest people dragged to the scaffold by Joseph Lebon; she makes him tell her how he was able to save himself at least from prison and tells him how much pleasure she and her older brother felt in receiving news of him from their younger brother; then Gaillard explains to her the embarrassment he finds himself in and asks her to help him with her advice to save the magistrates of Melun and the signatories of the address to Louis XVI.

”When my younger brother passed through Melun,” said Mlle Robespierre, ”all three of us were living together; I still hoped to be able to bring back the older, to snatch him from the wretches who obsess over him and lead him to the scaffold. They felt that my brother would eventually escape them if I regained his confidence, they destroyed me entirely in his mind; today he hates the sister who served as his mother… For several months he has been living alone, and although lodged in the same house, I no longer have the power to approach him… I loved him tenderly, I still do… His excesses are the consequence of the domination under which he groans, I am sure of it, but knowing no way to break the yoke he has allowed himself to be placed under, and no longer able to bear the pain and the shame of to see my brother devote his name to general execration, I ardently desire his death as well as mine. Judge of my unhappiness!… But let’s return to what interests you. The addresses to the king on the events of 1792 are already far from us; it seems to me that the signatures of these addresses are persecuted less than those who protested against the day of May 31. Try to see Maximilien, you will be content; he was very glad that our younger brother saw you at Melun. On this occasion he spoke with interest of the exercises of your pupils and of the attention you had in entrusting him with presiding over them. I won’t introduce you to him, I would not succeed; I even advise you not to speak to him about me. You will be told he is out, don't believe it, insist on your visit.”

The Robespierre family was housed on rue Saint-Honoré, near the Assomption chapel, the sister and younger brother at the front, the older brother at the back of the courtyard. Gaillard went to Maximilien’s apartment; a young man, looking at him with the most insolent air, said to him, barely having opened the door: “The representative isn’t home…”

“He may not be there for those who come to talk to him about business, but that is not my doing; I will talk to him about his family that I know a lot, you have seen me come out of his sister's apartment who is involved in state affairs no more than I am... Bring my name to the representative, he will receive me, I’m sure of it.”

The fellow did not dare refuse to carry a paper on which Gaillard had taken care to indicate himself in such a way as to be recognized, he immediately came back and gave the visitor his paper saying: “The representative does not know you,” and the door was violently slammed shut!…

The insolence of this brazen man whom Gaillard knew to be the secretary of Robespierre, son of Duplay, to whom the sister attributed the excesses of his brother, the sorrow he felt at losing the hope of saving the judges of Melun and to ensure his personal rest, all these thoughts made him very angry; he calls the young man a liar, insolent, he accuses him of deceiving Robespierre and of increasing the number of his enemies every day, all this in the loudest voice with the intention of being heard by Maximilien and lure him to one of the windows where, surely, he would have recognized him. New disappointment, no one appears and Gaillard goes back to tell Mlle Robespierre about his misadventure.

“I prepared you for it, she told him. ”No one can approach my brother unless he is a friend of those Duplays, with whom we are lodging; these wretches have neither intelligence nor education, explain to me their ascendancy over Maximilien. However, I do not despair of breaking the spell that holds him under their yoke; for that I am awaiting the return of my other brother, who has the right to see Maximilien. If the discovery I just made doesn't rid us of this race of vipers forever, my family is forever lost. You know what a miserable state we found ourselves in, reduced to alms, my brothers and I, if the sister of our father hadn’t taken us in. It’s strange that you didn’t often notice how much her husband’s brusqueness and formality made us pay dearly for the bread he gave us; but you must also have noticed that if indigence saddened us, it never degraded us and you always judged us incapable of containing money through a dubious action. Maximilien, who makes me so unhappy, has never given a hold, as you know, in terms of delicacy. Imagiene his fury when he learns that these miserable Duplays are using his name and his credit to get themselves the rarest goods at a low price from the merchants. So while all of Paris is forced to line up at the baker's shop every morning to get a few ounces of black, disgusting bread, the Duplays eat very good bread because the Incorruptible sits at their table: the same pretext provides them with sugar, oil, soap of the best quality, which the inhabitant of Paris would seek in vain in the best shops... How my brother's pride would be humiliated if he knew the abuse that these wretches make of his name! What would become of his popularity, even among his most ardent supporters? Certainly my brother is very proud, it is in him a capital fault; you must remember, you and I have often lamented the ridicule he made for himself by his vanity, the great number of enemies he made for himself by his disdainful and contemptuous tone, but he is not bloodthirsty. Certainly he believes he can overthrow his adversaries and his enemies by the superiority of his talent.”

The tenderness of this unfortunate girl for her brother was therefore very keen and very blind, she forgot that, a few moments before, she had told Gaillard, with the accent of despair and with eyes filled with tears, that death would seem preferable to the pain of seeing Maximilien dedicate his name to public execration, and yet her brother for his part had devoted mortal hatred to her since the trip she had made to Arras to collect evidence of the massacres carried out by Joseph Lebon.

“In the absence of my brother,” said Mlle Robespierre to Gaillard, would you like to try to see Couthon? He prides himself on being good for me, I will ask him to receive you, he will not refuse me, I will precede you by a quarter of an hour, he will give the order to let you in and we will exit together.”

Gaillard gratefully accepts, takes the address of Couthon who lived at n. 97 of the Cour du Manège, today rue de Rivoli, near rue du 29 Juilliet, and the next morning arrives at the indicated time.

Couthon, whose face was truly angelic, wore a white dressing gown. A child of five or six years old, beautiful as Love, was between his father's legs; he had a young white rabbit in his arms which he was feeding alfalfa. Mme Couthon and Mlle Robespierre stood in the embrasure of a window overlooking the Tuileries.

“You (vous) are,” said Couthon to Gaillard, a friend of Mlle Robespierre, you therefore have every kind of right to my interest, tell me, citizen, how can I be of use to you?”

The fine face, the entourage of innocence, the tone, the manners of good company, this care not to use tutoient when everyone else did so, convinced Gaillard that the slander had attached itself in particular to the person of this worthy M. Couthon, he promises to undeceive all those with whom the deputy had relations.

“Citizen representative, one of your colleagues, Maure, deputy for Yonne, had recalled the former judges, all very honest people, to the courts of Melun, and everyone applauded this act of justice. The popular society was offended by this, it threatened Maure that it was going to denounce him to the Convention as a supporter of Louis XVI and his family, given that these judges had adhered to the address by which the directorate of the department complained of the outrages committed against the king on the day of June 20 1792. The next day your colleague issued a decree dismissing these judges who were not yet installed, and ordered the revolutionary committee to incarcerate them. Can you please tell me by which means these unfortunate judges can escape this act of severity?”

“Admit, citizen,” answered Couthon, “that the Convention is indeed to be pitied for being forced to send as commissioners to the departments a crowd of imbeciles who make it hated and who compromise liberty... Maure doesn’t have the strength to understand that true patriots were saddened and rightly outraged by this fatal day of June 20. The aristocrats, as one said then, were delighted by it, the crimes of the people seemed to them a means of forever losing liberty and reestablishing despotism... It was a duty to rise up against the violation of the home of the first official of the the State and the bloody outrages to which it was subjected that day. I signed an address in which our indignation was expressed in the most energetic terms and I am far from repenting of it. Have the judges you are talking to me about been arrested?”

“No, citizen.”

”That’s what I suspected, they will have been warned; in fact, one is not going to prison automatically, one will have their homes sealed and perhaps not be very eager to arrest them?… Can you assure me, citizen, that these judges are honest men?”

”The most honest people in the country!”

”Well, on reflection, I was going to give you bad advice... based on the distance from Melun to Paris, this is where they will come to hide, one will find them, there is no safety in the prisons of Paris. They'd better go home, they shall be given a guard, they won't even be incarcerated... but once again, how can it be made a crime to have signed these addresses?”

“Citizen,” continues Gaillard, with great emotion, you are convinced that the signatures of these addresses have not committed a crime, you are all-powerful in the Committee of Public Safety where your opinion always prevails. Today, seventy unfortunate people are being led to the scaffold, their condemnation based on nothing other than the signing of these addresses…”

Couthon's face changed, he suddenly takes on the tiger's mask, makes a movement to grab the bell pull... Mlle Robespierre rushes at him to stop him (he was paralyzed from the legs down), turns towards Gaillard and says to him: “Save yourself!” In the confusion into which all this throws him, Gaillard takes Couthon's hat, she notices it, warns him, he runs across the apartment and reaches the stairs. He had barely gone down eight or ten steps when he heard Mlle Robespierre shouting to him: “Go and wait for me at the Orangerie.” (The courtyard of the Orangerie was located at the end of the Terrace des Feuillants where Rue de Rivoli now meets Place de la Concorde).

When Gaillard was able to think, he wondered why the various sentries posted along the Feuillants terrace had not stopped him. A glance in a mirror while picking up his hat in Couthon's salon had told him how altered his face was. Even after leaving the deputy, he did not think he was safe, he did not take four strides without wondering if he was being pursued. He has barely gone down into the courtyard of the Orangery when he goes back up onto the terrace, looking anxiously to see if his good angel was arriving. As soon as he sees her, he runs towards her, loudly asking her five or six questions at the same time without paying attention to the crowd around them. Mlle Robespierre, calmer, tells him in a low voice that she will answer him when they have reached the Place de la Révolution.

“Explain to me, please,” said Gaillard to Mlle Robespierre as soon as they were offshore, ”your haste to tell me to take flight flee and why you held back Couthon in his chair?”

“You were fooled, my dear monsieur, by the profound hypocrisy of Couthon, I was completely fooled myself; I believed your judges saved and you forever at peace like all the signatories of these addresses to Louis XVI... Couthon only showed himself to be so good-natured in order to get to know the depths of your thoughts, you fell into his trap, I could not have avoided it more than you. Your bloody and so justly deserved reproach regarding the 63 victims of today struck in the hearth, my presence, even my confidence could not have stopped his vengeance. The members of the Committee of Public Safety each have five or six men at home who are resolute at their command, because they are constantly trembling. Had he reached the bell pull, this very afternoon you would have been placed in the tumbril alongside the 63 unfortunate people you wanted to save... Fortunately, I succeeded in making him ashamed of the crime he was going to commit by immolating a friend that I had brought to his house... Will he keep his word to me? I followed your conversation very attentively, you did not say a word from which Couthon could conclude that you do not live in Paris... Return home quickly, do not follow the ordinary route out of fear that, remembering the name of the city where your judges were to sit, he sends for men to follow you on the road to Melun.” (1)

Mlle Robespierre barely gives her protégé time to thank her and does not want him to accompany her back to her house. Gaillard leaves immediately without seeing his sister or the two dismissed judges, who have taken refuge in Paris.

(1) The story of Gaillard's visit to Couthon is reproduced almost word for word by M. Lenôtre, in his Paris révolutionnaire, vielles maisons, vieux papiers, 1900, La Brouette de Couthon, p. 279.* Mr. Lenôtre draws his story from the collection of Victorien Sardou's autographs. The note appearing among these authographs which speaks of Couthon comes from Fouché's papers: it is in fact Gaillard who, at the request of his friend Fouché, recorded in writing for him the narration of his interview with Couthon. Gaillard took pleasure in often recounting to the people with whom he was in contact this scene of which he had always retained such a terrifying impression of; this is the reason why it appears today in his memoirs.

*Worth noting is that Charlotte’s identitity is kept a secret in this account, she’s simply described as ”a lady.” This account also includes the detail of Couthon’s son starting to cry and the bunny he was holding getting pushed to the floor once his father gets mad.

#charlotte robespierre#robespierre#couthon#georges couthon#frev#someone should draw this…#or just make anything of it at all since this side of charlotte is somehow never brought up by today’s historians#like why she’s SO much more fun like this…#fouché#joseph fouché#girl physically restrains a member of the cps and (allegedly) gets accused of poisoning another

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

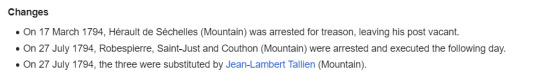

Changes in the Committee of the Public Safety:

71 notes

·

View notes

Photo

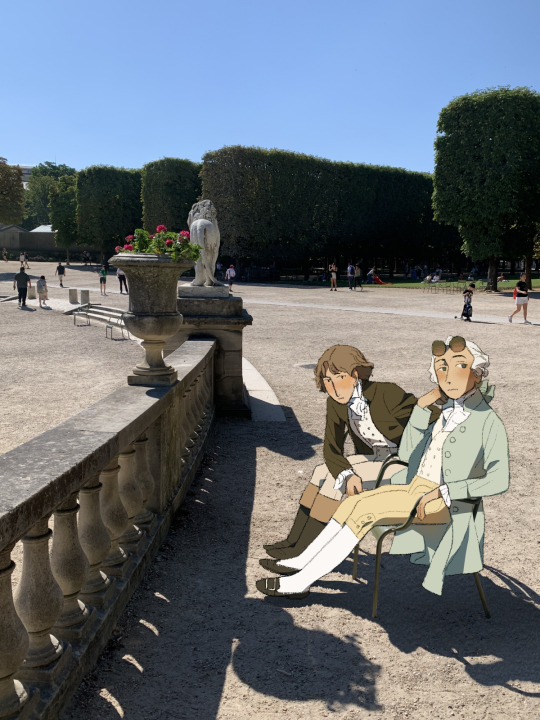

Joyeux 14 juillet ! Look who I found.....

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

The difference in treatment between the Indulgents and the Cordeliers or Hébertistes

I have an opinion that will seem unpopular, no worries I am open to any criticism or to being corrected in the event of an error so do not hesitate to correct me. I have much more sympathy for the Hébertist faction, the exaggerators or the Cordeliers than that of Danton's Indulgents. Indeed if we exclude the Hebert case who is an indefensible man, mediocre in my eyes (I don't think I need to explain why) this is not the case for so many others. I mean Ronsin was a competent and honest administrator.

Despite his mysoginism (horribly reprehensible, just look at the speech he gave concerning the execution of Gouges and Manon Roland) Chaumette could be as competent as procureur syndicale de Paris and had also generous ideas (such as banning whipping in schools, equalization of funeral rites for all, protective measures for the elderly and hospitalized).

One of the most impressive cases is Momoro. Even the historian Mathiez, who nevertheless has little sympathy for the revolutionaries who were against the Committee of Public Safety in the spring of 1794, had practically nothing but praise for Momoro. He voluntarily lived in poverty and when he was tried he said he had given everything for the revolution. It was true in my eyes.

Of course I understand in a certain way the repression exercised by the Committee of Public Safety (more precisely the Convention since an arrest cannot be made without its agreement, it is not a dictatorship either) when Cordeliers wanted to launch a new insurrection against the Convention ( like Momoro for example). The fact of wanting to persecute the priests did not help, not to mention the fact that they wanted stronger repression of the enemies at the risk of making the Revolution even harsher. But when we analyze, I can understand where come frome their anger. Their hatred about religion was due to the fact that not long ago, a lot of religious fanatics infantilized the people, constantly made prohibitions against them (we must NEVER accept infantilization or loss of free will for religious reasons) and atrocious repressions without counting the their wealth that they monopolized (in terms of absurd repression there is nothing but to see the Calas affair, or that of the case of Chevalier de la Barre etc…), even if there were a lot of priest and believers weren't like that . Although the Cordeliers were wrong to respond to religious intolerance by intolerance, I can agree. The same goes for the Terror. At that time France was threatened by enemies from within and without and quite a few of their enemies carried out atrocious tortures (although rotten people like Fouché, Carrier, were not to be outdone in atrocities to the point that the Committee of Public Safety recalled them immediately). Prices were increasing because of the war, so without excusing them once again I can understand their minds when they demanded ever greater repression of the Terror (even if once again it was a serious error ,a mistake and even a fault).

Let's compare to the indulgent (or Dantonists) who are caught up in financial scandals (according to for a lot of historians like Jean Marc Schiappa). Danton moved only because of the financial scandals which were beginning to erupt and did not dare to attack head-on in this period of factional clashes, he let his friends do so. Moreover, according to certain historians like Decaux if I am not mistaken, he only came back against the Hebertists because they attacked them (and they did not only have them as enemies). He is not a clean character. Let's not talk about Fabre d'Eglantine. For Desmoulins I have an unpopular opinion of him. I find him very overrated and no matter how much I tried to appreciate his historical figure (by reading the very good biography of Leuwers or the book by Joseph Andras) I cannot. I don't think that despite the fact that he is very cultured, a man who rightly think that women must have the right of vote and even a republican before his time, he is not capable of assuming an important position unlike Saint Just or Ronsin who he made fun of. And worst of all I find him hypocritical, he who demanded clemency applauded the execution of the Hebertists following a parody of justice (yes I like the Montagnards of this period but this kind of thing should never be tolerated) . He didn't say anything when the wives of Momoro and Hebert were arrested which was very serious (afterwards I don't know well if they were arrested at the same time as Lucile Desmoulins), but he didn't realize that it was going well back in his face.

The Dantonists were irresponsible in my eyes. I completely agree that it was necessary to examine each prisoner on a case-by-case basis because there were surely a large number who had nothing to do there by creating as many commissions as possible as quickly as possible and getting down to business. job right away because prison is a horrible place, even more so for innocent people. But releasing everyone without distinction immediately would have been dangerous because there were also dangerous counter-revolutionaries or spies. I mean have they forgotten that the fall of Toulon to the English was due to betrayal? The betrayal of Dumouriez, the assassinations of some deputies, etc…

Where did this idea of making peace with foreign armies still occupying France come from when the French army was beginning to be victorious? Opposing a war of conquest I completely agree, but allowing one's own territory to be annexed is something else.

And how dangerous would it be to leave corrupt people like Danton in power. Sooner or later, he could perhaps have given in to blackmail in view of the evidence of corruption that contemporaries have today, which would have been very dangerous for France.

As a result, I never understood why the “good” indulgent ones were portrayed against the “bad” Cordeliers and Hébertists.

Whatever happens for all these factions, no matter my great admiration for revolutionaries like Le Bas, Saint Just, Couthon, the fact that I am sorry like many people that Robespierre is demonized, the fact that they allowed a parody of justice against these factions is an unforgivable fault and to have allowed the execution of Marie Françoise Goupil and Lucile Desmoulins among others to consolidate this parody of justice is unacceptable. Even if I understand their states of mind because they could not afford to lose especially in this period against these different factions and contrary to what the Thermidorians put forward, the majority of the Convention was just as guilty as them, there is no excuse for this kind of behavior.

Did Saint Just realize this when he said that the Revolution was frozen (even he spoke more about the consequences of this repression and that the revolution is weakened on this point) ? It would later fall on them and Elisabeth Le Bas was threatened with being guillotined for having been Le Bas' wife (some wanted to force her into a marriage with one of the Termidorians). If they had not allowed the fate of Goupil or Lucile Desmoulins earlier perhaps it would have been more difficult for the Thermidorians to threaten her.

For more information in the form of a movie , I invite you to see" Saint Just ou la Force des Choses" and " la Camera explore le temps Danton, la terreur et la vertue" in English sub. These are good movies about this period.

And you what do you think ?

#french revolution#Terror#georges danton#Camille Desmoulins#Ronsin#Momoro#Cordeliers#Indulgents#History#saint just#couthon#robespierre#lucile desmoulins#Hebert#Chaumette#joseph fouché#Carrier

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm not joking when I say that I think about this letter Couthon sent to Saint-Just at least once a week. 'Embrace Herault' indeed.

#i just!!!!!#so much tragedy in this entire thing#the tragedy on a national level but the personal tragedy#on an individual level too#also couthon asking sj to embrace herault will never not be funny to me#the question is did sj actually go through with it 🤔#anyway#revolution eats its own etc etc#hate that#frev#herault de sechelles#saint-just#couthon#qui posts#TELL ME THAT YOU STILL EXIST#i will neVER shut up about this

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

welcome to the french revolution. we've got catty bitch of a journalist who got executed for being a catty bitch, even cattier bitch journalist who somehow didn't get executed but wrote from his bathtub, big loud guy who cheats on his wife and cheats in his financial reports, fancy dressed lawyer who takes his dog on two hour walks, broke 26 year old goth genius, a few women who burn down buildings and kill shopkeepers, another woman who suicide baited the dog walking lawyer, failed playwright who commits white collar crime, hot bisexual with an orgy cave, another journalist whose paper is primarily expletives, two guys who blew up civilians for no good reason, guy who brings a knife to the government to threaten his fellow officials, guy who thought he got paralyzed from having too much sex, asshole mathematician whose grandson became president of france, and a guy everyone calls bonbon.

#in order:#desmoulins#marat#danton#robespierre#saint just#the srrc#olympe de gouges#fabre#herault#hebert#fouche and collot#tallien#couthon#carnot#augustin#french revolution#frev#shitpost#pigeon.txt

352 notes

·

View notes

Text

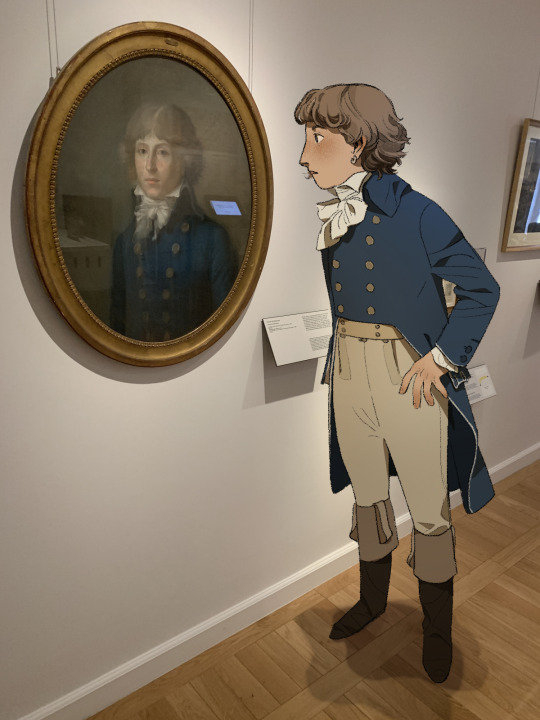

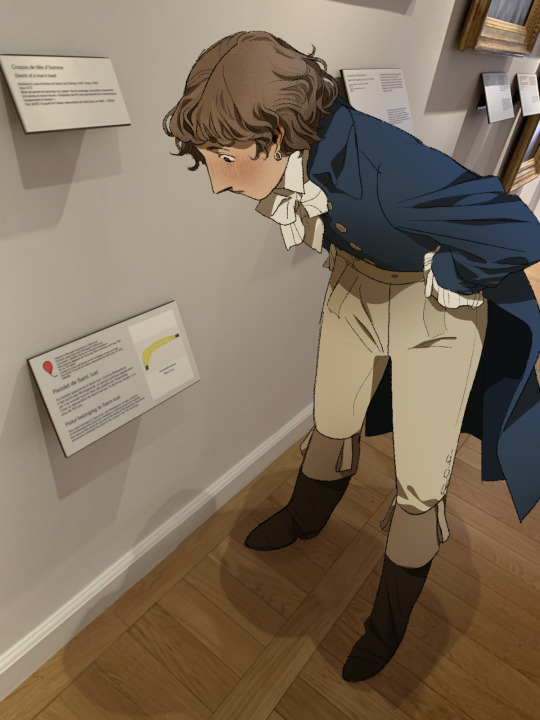

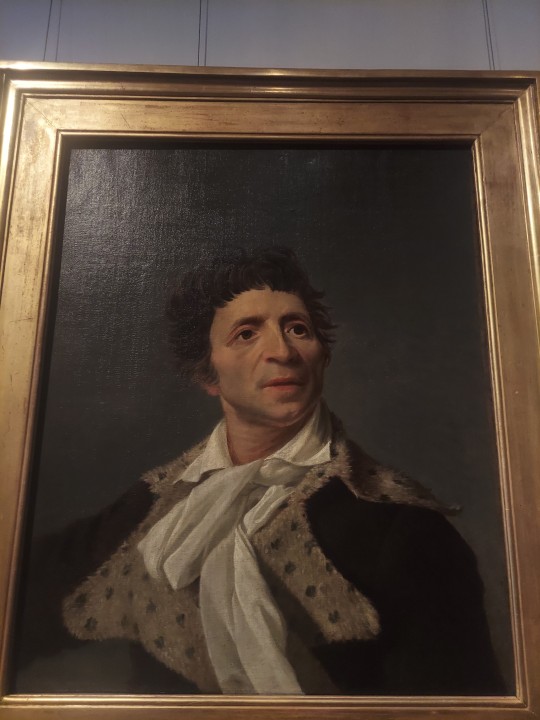

Some photos from Musée de Carnavalet 🥹🫶🏻 best day ever !

pics by me :)

205 notes

·

View notes

Text

Second in the Mapping the CPS series: a map of Ancien Regime France with the places of birth of our notorious third CPS. On the side, you can see a timeline with the date of birth of each of the members.

Some fun facts:

The average age of the Committee of Public Safety in July 1793 was 37, with Lindet being the oldest at 47 and Saint-Just the youngest at 25.

Couthon and Prieur (Cote d'Or) share a birthday on the 22 of December.

Three of the members (Lindet, Robespierre and Carnot) were born in May (so the CPS has 3 birthdays coming up!)

The only deputy of Paris that was actually born in Paris was Collot.

I'm surprised Billaud-Varenne wasn't sent on mission to the West (instead of Prieur de Marne and Saint-André) since he was born in La Rochelle, had family there and lived there until he was 26.

Saint-André shares a birthplace with Olympe de Gouges (a rather small town called Montauban)

Where all the members were born:

Robert Lindet: Bernay

Jean-Marie Collot d'Herbois: Paris

André Jeanbon Saint-André: Montauban

Lazare Carnot: Nolay

Bertrand Barère:Tarbes

Georges Couthon: Orcet

Jacques Billaud-Varenne: La Rochelle

Pierre-Louis Prieur de la Marne: Sommesous

Maximilien Robespierre: Arras

Marie-Jean Hérault de Séchelles: Paris

Claude-Antoine Prieur de la Côte-d’Or: Auxonne

Louis Antoine Saint-Just: Decize

#frev#french revolution#robespierre#committee of public safety#saint just#lindet#collot#saint-andre#lazare carnot#barere#couthon#billaud varenne#prieur#herault

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

I made a playlist of songs that I'm listening to while reading frev biographies! Some song choices were inspired by the revolution. Please give it a listen!!! Hope you guys enjoy it!!! :D

Under the cut are a few transparent pngs used in the album cover!

There are still a few ones left and I'll post them on their own later!

Have a good night, dear citizens, im signing out! :D

#maximilien robespierre#Robespierre#frev#french revolution#frev community#jean paul marat#marat#camille desmoulins#desmoulins#danton#georges danton#saint-just#saint just#antoine saint just#Antoine saint-just#georges couthon#couthon#herault de sechelles#herault#augustin robespierre#bonbon robespierre#charlotte robespierre#eleonore duplay#tea art 🎨#tea playlist#oklo makes a post

132 notes

·

View notes

Text

In an issue of Historia magazine, Hervé Leuwers wrote an uchrony in which Admirat succeeds in killing Robespierre.

So, he shoot him twice in the Duplay's courtward. Everyone is in shock.

In the evening, Barère asked at the Convention to pantheonize Robespierre. Legendre isn't very happy.

The next day, they take him to the Panthéon, coffin open, Marat's behind.

After the shock, the rage explosed. A lot of people think it's the British fault. No more english and hanovrian prisonners. The Revolutionary Tribunal took tougher actions.

A few weeks later, the pressure drops. No one know if they need to continue or not. The CPS emerged weakened.

July 1794, only Barere and Carnot remains in the CPS. Prisons are open.

Lecointre criticizes Billaud, Collot, Couthon and Saint-Just for supporting exceptional measures and concealing the crimes of representatives on mission, such as Carrier. A few weeks later, Billaud, Collot, Carrier and other Montagnards were imprisoned, while the Girondins were rehabilitated. The Convention decided to exclude Marat and Robespierre from the Pantheon.

-----------

Me :

#doomed uchrony#what about Charlotte and Bonbon ?#did they work it out ?#frev#robespierre#saint just#barrere#marat#couthon#billaud#no respect for billaud#i hate you Barere#collot#carnot comes through as always

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

#frev#history#french revolution#art#maximilien robespierre#robespierre#saint just#louis antoine de saint just#couthon#le bas#thermidor

129 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay so, a while ago I found this picture of the CSP, but I still struggle to identify everyone. From left to right: Saint-Just (he seems to radiate light e.e), Robespierre, Couthon, ??? (he could be Barère given the hairstyle and the fact he's staring at SJ, or Billaud since he looks lo much like this portrait of him), ???(no idea, maybe Hérault since he's very good-looking?), Collot, again no idea about the last three on the right.

Any suggestions?

65 notes

·

View notes

Note

What is the whole story of the law of 22 prairial? Who wrote it in the first place? Because I've learned that Georges couthon is the one who wrote it and not robespierre so I just wanna know everything and the background of this.

Tell me about it if you can, and what was the consequences of that law that came after?

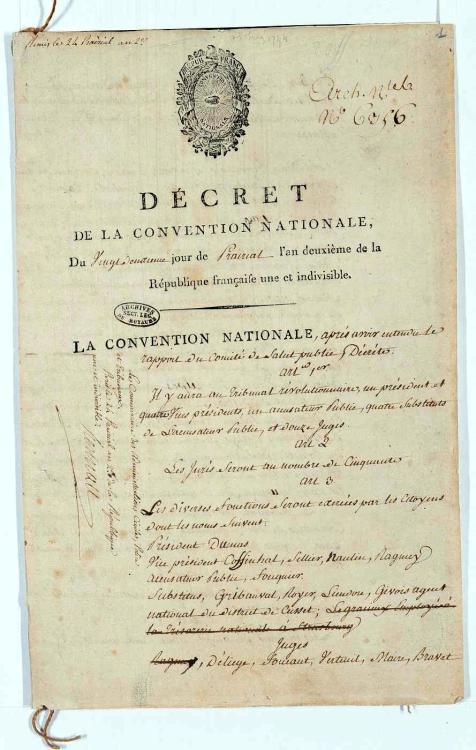

The law of 22 prairial has always been a hot topic of debate for historians, both when it comes to who exactly worked it out, as well as what the intended and actual consequences for it were.

If we start with the first of these questions — who was involved in the creation of the law? — it can be observed that the draft of it is in Couthon’s handwriting. This makes him the only person where any direct involvement in the development of the law can be truly established.

Today, this draft is apperently being kept at AN C 304, pl. 1126 et pl. 1127.

The law of 22 prairial does however share several undeniable similarities with the instruction decree for a commission at Orange, written on May 10 1794, exactly a month before Couthon’s draft was presented before the Convention. Below are the relevant extracts:

The decree for the commission at Orange

The duty of the members of the commission established at Orange is to jugde the enemies of the revolution.

The enemies of the revolution are all those who, by any means whatsoever and with any deeds they may have covered themselves, have sought to thwart the march of the revolution and to prevent the strengthening of the Republic.

The punishment for this crime is death.

The evidence required for the conviction is all information, of whatever nature, which can convince a reasonable man and friend of liberty. The rule of judgments is the conscience of judges enlightened by the love of justice and of the fatherland. Their goal, the public health and the ruin of enemies of the fatherland.

Law of 22 prairial

The Revolutionary Tribunal is instituted to punish the enemies of the people.

The enemies of the people are those who seek to destroy public liberty, either by force or by cunning. [there then follows a list of eleven actions that will deem you an enemy of the people]

The penalty provided for all offenses under the jurisdiction of the Revolutionary Tribunal is death.

The proof necessary to convict enemies of the people comprises every kind of evidence, whether material or moral, oral or written, which can naturally secure the approval of every just and reasonable mind; the rule of judgments is the conscience of the jurors, enlightened by love of the Patrie; their aim, the triumph of the Republic and the ruin of its enemies; the procedure, the simple means which good sense dictates in order to arrive at a knowledge of the truth, in the forms determined by law.

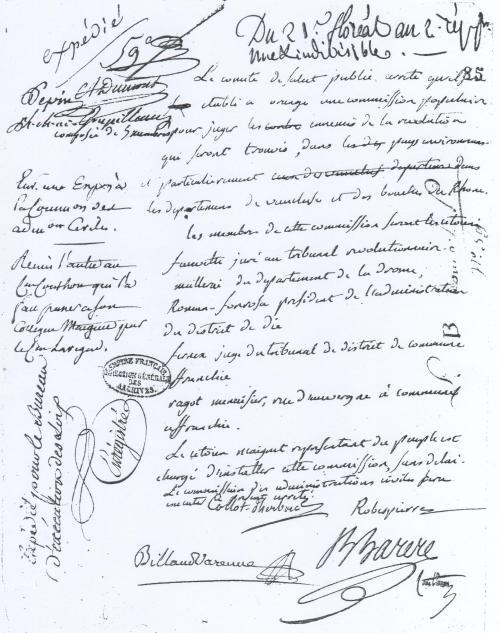

This time, the draft of the decree is in Robespierre’s handwriting (see the image below), and was signed by him, Collot d’Herbois, Couthon, Barère, Billaud-Varennes and Carnot. This, together with Robespierre’s undeniable support for the law of 22 prairial, is was has led some historians to want to give him and Couthon equal responsibility for it. There does however exist no real proof for Robespierre being the actual author behind the draft for the law of 22 prairial, nor evidence that he was the mastermind behind the law and just got Couthon to write it, as stated by his enemies after his death (see for example Robespierre peint par lui-même et condamné par ses propres principes… (1794) by Laurent Lecointre).

Today kept at AN, F7 4435, p. 3, pl. 85

When it comes to the involvement of anyone else in the development of the law of 22 prairial, Barère, Billaud-Varennes and Collot d’Herbois would in their Réponse des membres des deux anciens comités de salut public et de sûreté générale… (1795) claim that the law had been secretly worked out between Robespierre and Couthon — the rest of the CPS had not only had nothing to do with it, but even protested against it.

Is it not known to all citizens since the sessions of 12 and 13 Fructidor, that the decree of 22 Prairial was the secret work of Robespierre and Couthon, that it never, in defiance of all customs and all rights, was discussed or communicated to the Committee of Public Safety? No, such a draft would never have been passed by the committee had it been brought before it. […] At the morning session of 22 floréal [sic, it clearly means prairial], Billaud-Varennes openly accused Robespierre, as soon as he entered the committee, and reproached him and Couthon for alone having brought to the Convention the abominable decree which frightened the patriots. It is contrary, he said, to all the principles and to the constant progress of the committee to present a draft of a decree without first communicating it to the committee. Robespierre replied coldly that, having trusted each other up to this point in the committee, he had thought he could act alone with Couthon. The members of the committee replied that we have never acted in isolation, especially for serious matters, and that this decree was too important to be passed in this way without the will of the committee. The day when a member of the committee, adds Billaud, allows himself to present a decree to the Convention alone, there is no longer any freedom, but the will of a single person to propose legislation.

Against this be lifted the fact that Barère described the law of 22 prairial as ”a law completely in the favor of the patriots” when it was introduced (in the name of both the CPS and CGS, it might be added) to the Convention on June 10, and that both he and Billaud-Varennes stood on Robespierre’s side when the law was being criticised on June 12 (albeit this time they didn’t strictly speak about the law in itself). Furthermore, Collot d’Herbois, Barère, Billaud-Varennes and Carnot, as mentioned above, had actually co-signed the decree for the Commission of Orange on May 10, which suggests that, if they had a problem with the law of 22 prairial, it’s at least unlikely it had to do with the articles it had in common with said decree. All that said, like in the case of Robespierre, there is no solid proof of anyone besides Couthon having worked on the draft.

The historian Léonard Gallois wanted in his Historie de la Convention par elle-même (1835) to give the principal authorship of the law of 22 prairial not to Couthon, but to René-François Dumas, the president of the revolutionary tribunal. This based on the fact that Dumas, according to Gallois, ”didn’t cease to explain to the Committee of Public Safety that it was impossible to legally reach all the enemies of the people and conspirators when these found defenders, allegedly mindful, who held them to ransom, or who insulted revolutionary justice.” On May 30 at the Jacobins, Dumas did indeed suggest ”not to lightly grant unofficial defenders to all those who come to ask for them” and asked ”that a decree stipulating that no unofficial defender may not be granted without the Committee having previously examined the case for which one is requested, be strictly enforced.” Fouquier-Tinville, the public prosecutor, also reported the following in his defence (1795):

On 19 Prairial, I was in the council chamber with Dumas and several jurors. I heard the president speak of a new law which was being prepared and which was to reduce the number of jurors to seven and nine per sitting. That evening I went to the Committee of Public Safety. There I found Robespierre, Billaud, Collot, Barère and Carnot. I told them that the Tribunal having hitherto enjoyed public confidence, this reduction, if it took place, would infallibly cause it to lose it. Robespierre, who was standing in front of the fireplace, answered me with sudden rage, and ended by saying that only aristocrats could talk like that. None of the other members present said a word. So I withdrew. I went to the Committee of General Security, where I was told that they had no knowledge of this work. Two days later, on the 21st, President Dumas spoke again in the council chamber of this new law which was about to be passed, and which would abolish interrogations, written declarations and defenders. That evening again I went to the Committee of Public Safety. There I found Billaud, Collot, Barère, Prieur and Carnot. I informed them of this fact. They told me that it was none of their business, only Robespierre was in charge of this work. They wouldn't tell me more. I went to the Committee of General Security where I found Vadier, Amar, Dubarran, Voulland, Louis du Bas-Rhin, Moses Bayle, Lavicomterie and Elie Lacoste. I showed them my concern. All answered me that such a law was not in the status of being adopted.

While Gallois’ account has not been repeated by other historians (seeing as, again, Couthon’s handwriting is the only one which can be spotted on the draft), it’s also not impossible pressure from people like Dumas inspired the law, especially as he was close to the robespierrists (he is listed on second place on a list of patriots written by Robespierre).

When it comes to the second question — what was the intention with the law? — the historian Annie Jourdan summarized rather neatly the different main theories that have been laid out by historians over the years in a 2016 article titled Les journées de Prairial an II: le tournant de la Révolution ? (which I really recommend for anyone wishing to learn more about all the questions asked here). Franky, I think they all are probably true to some extent, one doesn’t have to exclude the other.

The first interpretation goes that the law was a response to the two failed assassination attemps against Collot d’Herbois and Robespierre on May 22 and 23. These events, the supporters of this theory argue, rattled the Convention in general (who viewed them as part of a bigger, English conspiracy) and Robespierre in particular (see for example this speech he held about it and this letter recalling Saint-Just to Paris written in his hand, both dated May 25 and both rather panicky in tone, as well as a claim made by the deputy Vilate that Robespierre during the last months of his life could speak only of assassination — ”he was frightened his own shadow would assassinate him.”) and this ”law of wrath” to borrow an expression from Hervé Leuwers, was the response, meant to act as the ultimate instrument of defense to protect the regime. What speaks against this being the full truth is the fact that the Orange decree existed already before the assassination attempts, which, as seen, contains much of the same content.

The somewhat opposite interpretation is that the law, instead of a passionate reaction to a sudden event, was a rational response to the Parisian revolutionary justice’s ongoing development. On May 8 1794, a decree had been passed ordering all local revolutionary tribunals (with a few exceptions) be closed and all suspects tried in front of the Revolutionary Tribunal in Paris. Naturally, this had caused overcrowding in the prisons of the capital a month later, and a law which speeded up the administration of justice therefore became a servicable solution. A similar line of thought is that the law was one in a series of decrees with the aim of bringing more power for Committee of Public Safety (we already have the law of 14 frimaire (December 4), the decree of 27 germinal (16 April) and the above mentioned decree of 19 floréal (8 May).

The third interpretation is that Robespierre and Couthon wanted to use the law of 22 prairial to be able to lay their hands on Convention deputies they thought needed to be purged. The law contained an article more or less stripping the Convention of its exclusive right to bring its representatives before the Revolutionary Tribunal. This was what said representatives took the biggest issue with, and on June 11,while Couthon and Robespierre were absent, they talked about scrapping it, something that however was undone the next day when the two came back, proving that that article was important to them. Historians especially sympathetic to Robespierre have argued that purging Convention deputies was his only intended purpose with the law (see for example Albert Mathiez who in his Robespierre terroriste (1920) wrote ”It therefore seems quite likely that by passing the law of 22 Prairial, Robespierre only aimed to punish five or six currupt and bloodthirsty proconsuls who had made the Terror the instrument of their crimes.”) But if that’s the case I wonder why Robespierre also personally contributed to making sure people who very clearly were not proconsuls were put under the mercy of the law (the most obvious example being his contribution to the prison conspiracies, where prisoners were brought before the tribunal in big groups to more or less be judged collectively).

A fourth interpretation goes that the reasoning behind the law was neither emotional nor practical, but ideological. Opposing the former interpretation, where it would only have been the question of using the law against only a small number of deputies, this one argues that it was aimed towards all counterrevolutionaries all over France, in an attempt to finally exterminate them all and thus create the ”virtuous republic” Robespierre talks about in his very last speech on 8 thermidor. Against this interpretation can be lifted the fact that Robespierre seemingly protests against the latest bloody developments in the same speech (though while simultaneously asking that revolutionary justice stays the way it currently is…)

Finally, when it comes to what the actual consequences for the law were, it is undeniable that it contributed to what we today call ”the great terror”, that is, the bloody parisian summer of 1794 during which, between the law’s passing on June 10 and the fall of Robespierre on July 27, 1366 people were executed. Exactly how much it is to blame has however been debated. While older historians have wanted to put all the blame almost exclusively on the law, more recent ones have argued that bickering, overlapping and rivalries between different operative bodies made the whole system work badly and that this was the true cause of the bloodletting, and that the law of 22 prairial would not have multiplied the amount of executions had only things around it worked properly.

#law of 22 prairial#robespierre#couthon#georges couthon#maximilien robespierre#frev#french revolution#ask#long post

55 notes

·

View notes