#coleoidea

Text

“Oh god,” Annabeth moaned, which let her aunt respond with a harsh “Hush!”

It shut Annabeth immediately up, however, it did nothing to ease the feeling of uneasiness rumbling through her.

The Chases followed people and came to a halt when they got closer to the ballroom. The line moved slowly, but Annabeth could pick up Sir Hermes’ voice announcing each guest.

“Lady Nathalie Chase and Lady Anna Chase,” Sir Hermes’ booming voice roared.

Annabeth thought about fleeing but the stern grip on her arm let her know her place. Nathalie dragged her into the large ballroom where all eyes were on them. Curiosity. Disdain. Disbelief. Amusement. No matter who’s gaze Annabeth came across, it was one of the four emotions she could read in people's faces. The big question, who she was, was mumbled through the rows. Quite a few of the dandies were shamelessly gawking at her. Everyone had seen her picture, likely in the Oliveirian Times. She hadn’t read the paper this morning.

Annabeth’s eyes focused on the people in front of her. The King and the Queen sat on golden thrones padded with the finest bordeaux-colored satin. The Queen sat upright on her throne, it was less embellished in comparison to the King’s throne. A variety of symbols had been carved into his throne, different animals such as birds and lions but also scrolls and swords.

The King himself looked rather tired. Even though the Queen had been old, he was most definitely older and Annabeth would have bet a mighty sum to say that he would rather be in bed, reading a good book than commencing the newest season.

Coleoidea my beloved 🫶🏾 you will be published this year, I promise… I’ll try to continue to work on you later this year 🥺

Writing tags: 1 | 2

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

(Correcting the previous question)

Is there a Cecaelia, a hybrid woman-octopus creature in any mythology?

According to Wiktionary, the term was

Apparently coined around 2007 on a discussion thread on Seatails, a mermaid-enthusiast messageboard created by Kurt Cagle, who created a Wikipedia article on the cecaelia (originally “Cecælia”), inspired by Cilia (a cilophyte in “Cilia”, a seven-page short comic story published in issue #16 of the Vampirella comic magazine, released in March of 1972), cilophyte, Coleoidea, and the song “Cecelia” by Simon and Garfunkel, about a fickle and demanding lover (according to Cagle).

They cite Hayward (2017), who says

The entity’s name appears to derive from a single source text, a short pictorial story published in Vampirella magazine entitled ‘Cilia’ (Cuti and Mas 1972) that became the basis for the more general figure of the ‘cecaelia’ some time in the late 2000s.”

Alright but is there actually a woman-octopus hybrid in mythology?

No, not that I know of. There are octopuses, and there are women, but I’ve never run into octopus women.

However, this is off the top of my head. I’ll go have a little literature dive and see if anything turns up.

114 notes

·

View notes

Note

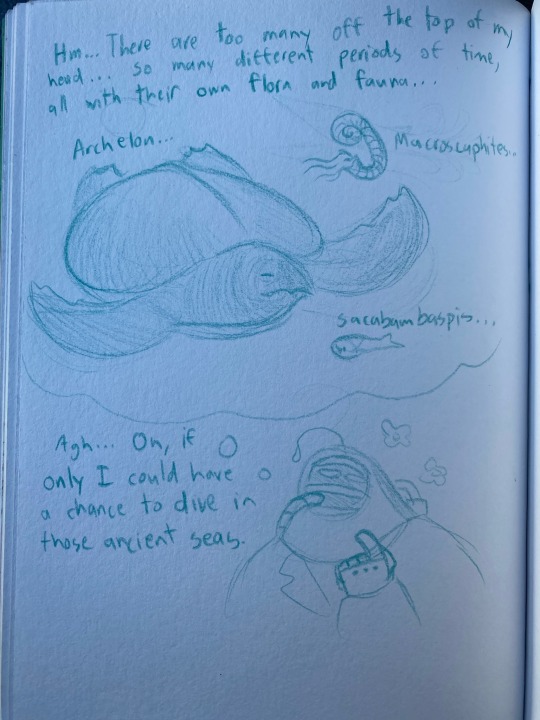

Do you know any ancient sea creatures that you really like, like any specific trilobites or dickinsonia or the famous animalocaris

This world has lived for billions of years, and through out the ages the ocean was filled to the brim with a whole plethora of sea creatures. To the Cambrian Explosion to the age of the dinosaurs, countless species “rules” the oceans. Forgive my sketches here, they could never encapsulate the true glory and scale of these creatures.

One creature that may seem familiar is the Macroscaphite, belonging to the extinct subclass of Cephalopods named Ammonoidea. You may know them better as the common name of “ammonite”. One may be familiar with the modern day Nautilus and assume that it is a long lasting member of this subclass due to their striking similarities, but ammonite were actually closer related to the subclass Coleoidea. This is the group of shell-less cephalopods such as octopi and squid.

Back in the day many ammonites had rather absurd shells, not just the polite little spiral you may sea in many textbooks. Some where cones spiraling up in the most ridiculous manner, some possessed dangerous ridges and spikes, others… well, as you can see with Macroscaphite… I cannot even begin to describe what this shape reminds me of. It is somewhere between a trombone, a paper clip, and a slide whistle. It is as if they all came together and had an abyssal child together, how beautiful.

Sacabambaspis is a mouthful of a name, which is funny to conchsider when you remember that it is a jawless genus of fish. “But Mary,” you say, “how can this fish eat without a jaw?” For this you can look to living examples such as lampreys and hagfish. These specimen can latch onto larger animals like a suction cup. Adult lampreys are parasitic in nature, scraping a “tongue” against their host for a good mouthful of meat. This does not kill the host, that would be bad for the parasite, but it is rather uncomfortable to say the least. I’m saying this from experience. Not enough is known about Sacabambaspis as a whole to say if it was a parasite itself. It is likely that it employed a similar sucking motion to collect food.

As for the Archelon… What a magnificent creature it is, no? The largest documented turtle to swim the seas. Approximately 15ft from head to tail, this reptile would’ve been taller than I am! Can you imagine that? Someone larger than me? There are the boss cogs, yes, but outside of that bunch there aren’t many who rival me in size. Much like the living leatherback sea turtle, Archelon would’ve had a leathery shell, or carapace, unlike other hard shelled turtles. Who knows what prehistoric jellyfish or squid this beast may have consumed. It is hard to imagine such a large fortress of an animal to be contested in its oceans, but during its life the Archelon would’ve shared its waters with large marine reptiles such as the mosasaur.

[The Deep Diver sighs, shutting her notebook and tucking it into a comically small pocket on her suit.]

If only I could have the chance to meet these creatures, even if it is only for a moment… oh well. No reason to dwell in the past, to have suck silly dreams swimming around in my helmet.

34 notes

·

View notes

Note

do you think cuttlefish could be a third inkling/octoling type species considering theyre all very closely related coleoidea??

a lot of ppl ask about cuttlefish in splatoon... they exist already!

they look similar to inklings too, difference being that they have wavy fins in their tentacle hair to reflect the fins of a cuttlefish. makes sense theyd look so similar with how real like squid and cuttlefish look so alike.

tho i dont know if they would be a third playable species because unlike octolings, they werent in hiding and seem to have always existed alongside inklings with no issues + again they just look like inklings with even slighter differences than the octolings

i cant think of a good story reason for them to suddenly become playable either, other than "they are rare in inkopolis/splatlands and mostly are in some other region".

i like to think that in universe, cuttlefish just play turf wars alongside inklings but its just not reflected in game...kinda like how in universe we can easily imagine inklings and octos that arent all just same face same body type same height, but its not reflected in game.

#unrelated to this ask but can the squid sisters are cuttlefish theory be dead and buried already#especially with ROTM#asks#cuttlefish

168 notes

·

View notes

Text

Intro and Sophont List

This is a DnD rehaul inspired by @danbensen's Fellow Tetrapod story.

All races and classes available to DnD 5e will be reinterpreted as a sophont according to his guide for making FT sophonts. (Skill trees will be available for each sophont species).

Sophonts currently in FT will not be added until the current workload is complete. Sophont list below, although it's a heavy WIP.

Humans (Human, Hominid)

Noxissum (Aaracrocka, Pelagornis) -> thrill-seeking sophonts that live on cliffsides

Volutor (Aasimar, Polyneoptera)

Fixers [of Flesh] (Autognome, Canis) -> climbing oophagous sophonts with a focus on hunger

? (Bugbear, Barbourofelidae)

Harvau (Centaur, Mesohippus)

? (Changeling, Coleoidea)

Hemadele (Dhampir, Geospiza) -> blood-drinking sophonts that trade themselves for food

Deager (Dragonborn, Toxicofera) -> artistic sophonts with sprayed venom that dyes

Korrines (Dwarf, Herpestoidea) -> burrowing sophonts with deep familial bonds

Helbosi (Elf, Acariformes)

? (Fairy, Microraptoria)

? (Firbolg/Giant/Goliath, Pecora)

? (Genasi, Spiralia)

Breakers [They that Break the Waves] (Gnome, Otariidae)

? (Goblin, Holocephali)

? (Halfling, Callitrichidae)

? (Kenku, Corvides)

? (Kobold, Isoptera)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

please i hope 10 million undiscovered coleoidea 🙏

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

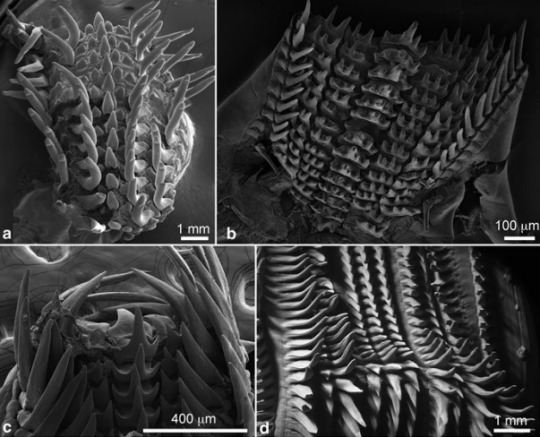

Micrographs of radulae of recent cephalopods

a) Radula of Nautilus pompilius (Nautilidae, Nautiloidea). UMUT unregistered specimen. From off Suva, Fiji.

b) Radula of Japetella diaphana (Octopoda, Amphitretidae).

c) Radula of Loligo pealei (Loliginidae, Coleoidea).

d) Radula of Dosidicus gigas (Humboldt squid, Ommastrephinae, Coleoidea)

From Isabelle Kruta, Neil H. Landman and Kazushige Tanabe's "Ammonoid Radula" via ResearchGate

0 notes

Text

I am Squid. He/they/it. 13'10", thanks for asking. Magic anons are fine. I came from the ocean. And that is my home.

I eat meat. I prefer seafood. But I certainly don't mind a good steak.

Collect my fish. (I'm hungry.) Also, collect all this darn trash. You land dwellers made it, not me. And it's not quite fair for me to have to deal with it.

A squid (pl.: squid) is a mollusc with an elongated soft body, large eyes, eight arms, and two tentacles in the superorder Decapodiformes, though many other molluscs within the broader Neocoleoidea are also called squid despite not strictly fitting these criteria. Like all other cephalopods, squid have a distinct head, bilateral symmetry, and a mantle. They are mainly soft-bodied, like octopuses, but have a small internal skeleton in the form of a rod-like gladius or pen, made of chitin.

Squid diverged from other cephalopods during the Jurassic and occupy a similar role to teleost fish as open water predators of similar size and behaviour. They play an important role in the open water food web. The two long tentacles are used to grab prey and the eight arms to hold and control it. The beak then cuts the food into suitable size chunks for swallowing. Squid are rapid swimmers, moving by jet propulsion, and largely locate their prey by sight. They are among the most intelligent of invertebrates, with groups of Humboldt squid having been observed hunting cooperatively. They are preyed on by sharks, other fish, sea birds, seals and cetaceans, particularly sperm whales.

Squid can change colour for camouflage and signalling. Some species are bioluminescent, using their light for counter-illumination camouflage, while many species can eject a cloud of ink to distract predators.

Squid are used for human consumption with commercial fisheries in Japan, the Mediterranean, the southwestern Atlantic, the eastern Pacific and elsewhere. They are used in cuisines around the world, often known as "calamari". Squid have featured in literature since classical times, especially in tales of giant squid and sea monsters.

Squid are members of the class Cephalopoda, subclass Coleoidea. The squid orders Myopsida and Oegopsida are in the superorder Decapodiformes (from the Greek for "ten-legged"). Two other orders of decapodiform cephalopods are also called squid, although they are taxonomically distinct from squids and differ recognizably in their gross anatomical features. They are the bobtail squid of order Sepiolida and the ram's horn squid of the monotypic order Spirulida. The vampire squid (Vampyroteuthis infernalis), however, is more closely related to the octopus than to any squid.[2]

The cladogram, not fully resolved, is based on Sanchez et al., 2018.[2] Their molecular phylogeny used mitochondrial and nuclear DNA marker sequences; they comment that a robust phylogeny "has proven very challenging to obtain". If it is accepted that Sepiidae cuttlefish are a kind of squid, then the squids, excluding the vampire squid, form a clade as illustrated.[2] Orders are shown in boldface; all the families not included in those orders are in the paraphyletic order "Oegopsida", except Sepiadariidae and Sepiidae that are in the paraphyletic order "Sepiida",

Crown coleoids (the common ancestor of octopuses and squid) diverged in the late Paleozoic (Mississippian), according to fossils of Syllipsimopodi, an early relative of vampire squids and octopuses.[3] True squid diverged during the Jurassic, but many squid families appeared in or after the Cretaceous.[4] Both the coleoids and the teleost fish were involved in much adaptive radiation at this time, and the two modern groups resemble each other in size, ecology, habitat, morphology and behaviour, however some fish moved into fresh water while the coleoids remained in marine environments.[5]

The ancestral coleoid was probably nautiloid-like with a strait septate shell that became immersed in the mantle and was used for buoyancy control. Four lines diverged from this, Spirulida (with one living member), the cuttlefishes, the squids and the octopuses. Squid have differentiated from the ancestral mollusc such that the body plan has been condensed antero-posteriorly and extended dorso-ventrally. What may have been the foot of the ancestor is modified into a complex set of appendages around the mouth. The sense organs are highly developed and include advanced eyes similar to those of vertebrates.[5]

The ancestral shell has been lost, with only an internal gladius, or pen, remaining. The pen, made of a chitin-like material,[5][6] is a feather-shaped internal structure that supports the squid's mantle and serves as a site for muscle attachment. The cuttlebone or sepion of the Sepiidae is calcareous and appears to have evolved afresh in the Tertiary.[7]

Squid are soft-bodied molluscs whose forms evolved to adopt an active predatory lifestyle. The head and foot of the squid are at one end of a long body, and this end is functionally anterior, leading the animal as it moves through the water. A set of eight arms and two distinctive tentacles surround the mouth; each appendage takes the form of a muscular hydrostat and is flexible and prehensile, usually bearing disc-like suckers.[5]

The suckers may lie directly on the arm or be stalked. Their rims are stiffened with chitin and may contain minute toothlike denticles. These features, as well as strong musculature, and a small ganglion beneath each sucker to allow individual control, provide a very powerful adhesion to grip prey. Hooks are present on the arms and tentacles in some species, but their function is unclear.[8] The two tentacles are much longer than the arms and are retractile. Suckers are limited to the spatulate tip of the tentacle, known as the manus.[5]

In the mature male, the outer half of one of the left arms is hectocotylised – and ends in a copulatory pad rather than suckers. This is used for depositing a spermatophore inside the mantle cavity of a female. A ventral part of the foot has been converted into a funnel through which water exits the mantle cavity.[5]

The main body mass is enclosed in the mantle, which has a swimming fin along each side. These fins are not the main source of locomotion in most species. The mantle wall is heavily muscled and internal. The visceral mass, which is covered by a thin, membranous epidermis, forms a cone-shaped posterior region known as the "visceral hump". The mollusc shell is reduced to an internal, longitudinal chitinous "pen" in the functionally dorsal part of the animal; the pen acts to stiffen the squid and provides attachments for muscles.[5]

On the functionally ventral part of the body is an opening to the mantle cavity, which contains the gills (ctenidia) and openings from the excretory, digestive and reproductive systems. An inhalant siphon behind the funnel draws water into the mantle cavity via a valve. The squid uses the funnel for locomotion via precise jet propulsion.[9] In this form of locomotion, water is sucked into the mantle cavity and expelled out of the funnel in a fast, strong jet. The direction of travel is varied by the orientation of the funnel.[5] Squid are strong swimmers and certain species can "fly" for short distances out of the water.[10]

Squid make use of different kinds of camouflage, namely active camouflage for background matching (in shallow water) and counter-illumination. This helps to protect them from their predators and allows them to approach their prey.[11][12]

The skin is covered in controllable chromatophores of different colours, enabling the squid to match its coloration to its surroundings.[11][13] The play of colours may in addition distract prey from the squid's approaching tentacles.[14] The skin also contains light reflectors called iridophores and leucophores that, when activated, in milliseconds create changeable skin patterns of polarized light.[15][16] Such skin camouflage may serve various functions, such as communication with nearby squid, prey detection, navigation, and orientation during hunting or seeking shelter.[15] Neural control of the iridophores enabling rapid changes in skin iridescence appears to be regulated by a cholinergic process affecting reflectin proteins.[16]

Some mesopelagic squid such as the firefly squid (Watasenia scintillans) and the midwater squid (Abralia veranyi) use counter-illumination camouflage, generating light to match the downwelling light from the ocean surface.[12][17][18] This creates the effect of countershading, making the underside lighter than the upperside.[12]

Counter-illumination is also used by the Hawaiian bobtail squid (Euprymna scolopes), which has symbiotic bacteria (Aliivibrio fischeri) that produce light to help the squid avoid nocturnal predators.[19] This light shines through the squid's skin on its underside and is generated by a large and complex two-lobed light organ inside the squid's mantle cavity. From there, it escapes downwards, some of it travelling directly, some coming off a reflector at the top of the organ (dorsal side). Below there is a kind of iris, which has branches (diverticula) of its ink sac, with a lens below that; both the reflector and lens are derived from mesoderm. The squid controls light production by changing the shape of its iris or adjusting the strength of yellow filters on its underside, which presumably change the balance of wavelengths emitted.[17] Light production shows a correlation with intensity of down-welling light, but it is about one third as bright; the squid can track repeated changes in brightness. Because the Hawaiian bobtail squid hides in sand during the day to avoid predators, it does not use counter-illumination during daylight hours.[17]

Squid distract attacking predators by ejecting a cloud of ink, giving themselves an opportunity to escape.[20][21] The ink gland and its associated ink sac empties into the rectum close to the anus, allowing the squid to rapidly discharge black ink into the mantle cavity and surrounding water.[8] The ink is a suspension of melanin particles and quickly disperses to form a dark cloud that obscures the escape manoeuvres of the squid. Predatory fish may also be deterred by the alkaloid nature of the discharge which may interfere with their chemoreceptors.[5]

Cephalopods have the most highly developed nervous systems among invertebrates. Squids have a complex brain in the form of a nerve ring encircling the oesophagus, enclosed in a cartilaginous cranium. Paired cerebral ganglia above the oesophagus receive sensory information from the eyes and statocysts, and further ganglia below control the muscles of the mouth, foot, mantle and viscera. Giant axons up to 1 mm (0.04 in) in diameter convey nerve messages with great rapidity to the circular muscles of the mantle wall, allowing a synchronous, powerful contraction and maximum speed in the jet propulsion system.[5]

The paired eyes, on either side of the head, are housed in capsules fused to the cranium. Their structure is very similar to that of a fish eye, with a globular lens that has a depth of focus from 3 cm (1.2 in) to infinity. The image is focused by changing the position of the lens, as in a camera or telescope, rather than changing the shape of the lens, as in the human eye. Squid adjust to changes in light intensity by expanding and contracting the slit-shaped pupil.[5] Deep sea squids in the family Histioteuthidae have eyes of two different types and orientation. The large left eye is tubular in shape and looks upwards, presumably searching for the silhouettes of animals higher in the water column. The normally-shaped right eye points forwards and downwards to detect prey.[22]

The statocysts are involved in maintaining balance and are analogous to the inner ear of fish. They are housed in cartilaginous capsules on either side of the cranium. They provide the squid with information on its body position in relation to gravity, its orientation, acceleration and rotation, and are able to perceive incoming vibrations. Without the statocysts, the squid cannot maintain equilibrium.[5] Squid appear to have limited hearing,[23] but the head and arms bear lines of hair-cells that are weakly sensitive to water movements and changes in pressure, and are analogous in function to the lateral line system of fish.[5]

The sexes are separate in squid, with a single gonad in the posterior part of the body. Fertilisation is external and usually takes place in the mantle cavity of the female. The male has a testis from which sperm pass into a single gonoduct where they are rolled together into a long bundle, or spermatophore. The gonoduct is elongated into a "penis" that extends into the mantle cavity and through which spermatophores are ejected. In shallow water species, the penis is short, and the spermatophore is removed from the mantle cavity by a tentacle of the male, which is specially adapted for the purpose and known as a hectocotylus, and placed inside the mantle cavity of the female during mating.[5]

The female has a large translucent ovary, situated towards the posterior of the visceral mass. From here, eggs travel along the gonocoel, where there are a pair of white nidamental glands, which lie anterior to the gills. Also present are red-spotted accessory nidamental glands containing symbiotic bacteria; both organs are associated with nutrient manufacture and forming shells for the eggs. The gonocoel enters the mantle cavity at the gonopore, and in some species, receptacles for storing spermatophores are located nearby, in the mantle wall.[5]

In shallow-water species of the continental shelf and epipelagic or mesopelagic zones, it is frequently one or both of arm pair IV of males that are modified into hectocotyli.[24] However, most deep-sea squid lack hectocotyl arms and have longer penises; Ancistrocheiridae and Cranchiinae are exceptions.[25] Giant squid of the genus Architeuthis are unusual in that they possess both a large penis and modified arm tips, although whether the latter are used for spermatophore transfer is uncertain.[25] Penis elongation has been observed in the deep-water species Onykia ingens; when erect, the penis may be as long as the mantle, head, and arms combined.[25][26] As such, deep-water squid have the greatest known penis length relative to body size of all mobile animals, second in the entire animal kingdom only to certain sessile barnacles.[25]

Like all cephalopods, squids are predators and have complex digestive systems. The mouth is equipped with a sharp, horny beak mainly made of chitin and cross-linked proteins,[27] which is used to kill and tear prey into manageable pieces. The beak is very robust, but does not contain minerals, unlike the teeth and jaws of many other organisms; the cross-linked proteins are histidine- and glycine-rich and give the beak a stiffness and hardness greater than most equivalent synthetic organic materials.[28] The stomachs of captured whales often have indigestible squid beaks inside. The mouth contains the radula, the rough tongue common to all molluscs except bivalvia, which is equipped with multiple rows of teeth.[5] In some species, toxic saliva helps to control large prey; when subdued, the food can be torn in pieces by the beak, moved to the oesophagus by the radula, and swallowed.[29]

The food bolus is moved along the gut by waves of muscular contractions (peristalsis). The long oesophagus leads to a muscular stomach roughly in the middle of the visceral mass. The digestive gland, which is equivalent to a vertebrate liver, diverticulates here, as does the pancreas, and both of these empty into the caecum, a pouch-shaped sac where most of the absorption of nutrients takes place.[5] Indigestible food can be passed directly from the stomach to the rectum where it joins the flow from the caecum and is voided through the anus into the mantle cavity.[5] Cephalopods are short-lived, and in mature squid, priority is given to reproduction;[30] the female Onychoteuthis banksii for example, sheds its feeding tentacles on reaching maturity, and becomes flaccid and weak after spawning.[31][32]

The squid mantle cavity is a seawater-filled sac containing three hearts and other organs supporting circulation, respiration, and excretion.[33] Squid have a main systemic heart that pumps blood around the body as part of the general circulatory system, and two branchial hearts. The systemic heart consists of three chambers, a lower ventricle and two upper atria, all of which can contract to propel the blood. The branchial hearts pump blood specifically to the gills for oxygenation, before returning it to the systemic heart.[33] The blood contains the copper-rich protein hemocyanin, which is used for oxygen transport at low ocean temperatures and low oxygen concentrations, and makes the oxygenated blood a deep, blue color.[33] As systemic blood returns via two vena cavae to the branchial hearts, excretion of urine, carbon dioxide, and waste solutes occurs through outpockets (called nephridial appendages) in the vena cavae walls that enable gas exchange and excretion via the mantle cavity seawater.[33]

Unlike nautiloids and cuttlefish which have gas-filled chambers inside their shells which provide buoyancy, and octopuses which live near and rest on the seabed and do not require to be buoyant, many squid have a fluid-filled receptacle, equivalent to the swim bladder of a fish, in the coelom or connective tissue. This reservoir acts as a chemical buoyancy chamber, with the heavy metallic cations typical of seawater replaced by low molecular-weight ammonium ions, a product of excretion. The small difference in density provides a small contribution to buoyancy per unit volume, so the mechanism requires a large buoyancy chamber to be effective. Since the chamber is filled with liquid, it has the advantage over a swim bladder of not changing significantly in volume with pressure. Glass squids in the family Cranchiidae for example, have an enormous transparent coelom containing ammonium ions and occupying about two-thirds the volume of the animal, allowing it to float at the required depth. About half of the 28 families of squid use this mechanism to solve their buoyancy issues.[5] The family Bathyteuthidae get their buoyancy from an oily substance found in their liver and around their mantle and head.[34]

The majority of squid are no more than 60 cm (24 in) long, although the giant squid may reach 13 m (43 ft).[35] The smallest species are probably the benthic pygmy squids Idiosepius, which grow to a mantle length of 10 to 18 mm (0.4 to 0.7 in), and have short bodies and stubby arms.[36]

In 1978, sharp, curved claws on the suction cups of squid tentacles cut up the rubber coating on the hull of the USS Stein. The size suggested the largest squid known at the time.[37]

In 2003, a large specimen of an abundant[38] but poorly understood species, Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni (the colossal squid), was discovered. This species may grow to 10 m (33 ft) in length, making it the largest invertebrate.[39] In February 2007, a New Zealand fishing vessel caught the largest squid ever documented, weighing 495 kg (1,091 lb) and measuring around 10 m (33 ft) off the coast of Antarctica.[40] Dissection showed that the eyes, used to detect prey in the deep Southern Ocean, exceeded the size of footballs; these may be among the largest eyes ever to exist in the animal kingdom.[41]

The eggs of squid are large for a mollusc, containing a large amount of yolk to nourish the embryo as it develops directly, without an intervening veliger larval stage. The embryo grows as a disc of cells on top of the yolk. During the gastrulation stage, the margins of the disc grow to surround the yolk, forming a yolk sac, which eventually forms part of the animal's gut. The dorsal side of the disc grows upwards and forms the embryo, with a shell gland on its dorsal surface, gills, mantle and eyes. The arms and funnel develop as part of the foot on the ventral side of the disc. The arms later migrate upwards, coming to form a ring around the funnel and mouth. The yolk is gradually absorbed as the embryo grows. Some juvenile squid live higher in the water column than do adults. Squids tend to be short-lived; Loligo for example lives from one to three years according to species, typically dying soon after spawning.[5]

In a well-studied bioluminescent species, the Hawaiian bobtail squid, a special light organ in the squid's mantle is rapidly colonized with Aliivibrio fischeri bacteria within hours of hatching. This light-organ colonization requires this particular bacterial species for a symbiotic relationship; no colonization occurs in the absence of A. fischeri.[19] Colonization occurs in a horizontal manner, such that the hosts acquires its bacterial partners from the environment. The symbiosis is obligate for the squid, but facultative for the bacteria. Once the bacteria enter the squid, they colonize interior epithelial cells in the light organ, living in crypts with complex microvilli protrusions. The bacteria also interact with hemocytes, macrophage-like blood cells that migrate between epithelial cells, but the mechanism and function of this process is not well understood. Bioluminescence reaches its highest levels during the early evening hours and bottoms out before dawn; this occurs because at the end of each day, the contents of the squid's crypts are expelled into the surrounding environment.[42] Approximately 95% of the bacteria are voided each morning before the bacterial population builds up again by nightfall.[17]

Squid can move about in several different ways. Slow movement is achieved by a gentle undulation of the muscular lateral fins on either side of the trunk which drives the animal forward. A more common means of locomotion providing sustained movement is achieved using jetting, during which contraction of the muscular wall of the mantle cavity provides jet propulsion.[5]

Slow jetting is used for ordinary locomotion, and ventilation of the gills is achieved at the same time. The circular muscles in the mantle wall contract; this causes the inhalant valve to close, the exhalant valve to open and the mantle edge to lock tightly around the head. Water is forced out through the funnel which is pointed in the opposite direction to the required direction of travel. The inhalant phase is initiated by the relaxation of the circular muscles causes them to stretch, the connective tissue in the mantle wall recoils elastically, the mantle cavity expands causing the inhalant valve to open, the exhalant valve to close and water to flow into the cavity. This cycle of exhalation and inhalation is repeated to provide continuous locomotion.[5]

Fast jetting is an escape response. In this form of locomotion, radial muscles in the mantle wall are involved as well as circular ones, making it possible to hyper-inflate the mantle cavity with a larger volume of water than during slow jetting. On contraction, water flows out with great force, the funnel always being pointed anteriorly, and travel is backwards. During this means of locomotion, some squid exit the water in a similar way to flying fish, gliding through the air for up to 50 m (160 ft), and occasionally ending up on the decks of ships.[5]

Squid are carnivores, and, with their strong arms and suckers, can overwhelm relatively large animals efficiently. Prey is identified by sight or by touch, grabbed by the tentacles which can be shot out with great rapidity, brought back to within reach of the arms, and held by the hooks and suckers on their surface.[43] In some species, the squid's saliva contains toxins which act to subdue the prey. These are injected into its bloodstream when the prey is bitten, along with vasodilators and chemicals to stimulate the heart, and quickly circulate to all parts of its body.[5] The deep sea squid Taningia danae has been filmed releasing blinding flashes of light from large photophores on its arms to illuminate and disorientate potential prey.[44]

Although squid can catch large prey, the mouth is relatively small, and the food must be cut into pieces by the chitinous beak with its powerful muscles before being swallowed. The radula is located in the buccal cavity and has multiple rows of tiny teeth that draw the food backwards and grind it in pieces.[5] The deep sea squid Mastigoteuthis has the whole length of its whip-like tentacles covered with tiny suckers; it probably catches small organisms in the same way that flypaper traps flies. The tentacles of some bathypelagic squids bear photophores which may bring food within its reach by attracting prey.[43]

Squid are among the most intelligent invertebrates. For example, groups of Humboldt squid hunt cooperatively, spiralling up through the water at night and coordinating their vertical and horizontal movements while foraging.[45]

Courtship in squid takes place in the open water and involves the male selecting a female, the female responding, and the transfer by the male of spermatophores to the female. In many instances, the male may display to identify himself to the female and drive off any potential competitors.[46] Elaborate changes in body patterning take place in some species in both agonistic and courtship behaviour. The Caribbean reef squid (Sepioteuthis sepioidea), for example, employs a complex array of colour changes during courtship and social interactions and has a range of about 16 body patterns in its repertoire.[47]

The pair adopt a head-to-head position, and "jaw locking" may take place, in a similar manner to that adopted by some cichlid fish.[48] The heterodactylus of the male is used to transfer the spermatophore and deposit it in the female's mantle cavity in the position appropriate for the species; this may be adjacent to the gonopore or in a seminal receptacle.[5]

The sperm may be used immediately or may be stored. As the eggs pass down the oviduct, they are wrapped in a gelatinous coating, before continuing to the mantle cavity, where they are fertilised. In Loligo, further coatings are added by the nidimental glands in the walls of the cavity and the eggs leave through a funnel formed by the arms. The female attaches them to the substrate in strings or groups, the coating layers swelling and hardening after contact with sea water. Loligo sometimes forms breeding aggregations which may create a "community pile" of egg strings. Some pelagic and deep sea squid do not attach their egg masses, which float freely.[5]

Squid mostly have an annual life cycle, growing fast and dying soon after spawning. The diet changes as they grow but mostly consists of large zooplankton and small nekton. In Antarctica for example, krill is the main constituent of the diet, with other food items being amphipods, other small crustaceans, and large arrow worms. Fish are also eaten, and some squid are cannibalistic.[49]

As well as occupying a key role in the food chain, squid are an important prey for predators including sharks, sea birds, seals and whales. Juvenile squid provide part of the diet for worms and small fish. When researchers studied the contents of the stomachs of elephant seals in South Georgia, they found 96% squid by weight.[50] In a single day, a sperm whale can eat 700 to 800 squid,[50] and a Risso's dolphin entangled in a net in the Mediterranean was found to have eaten angel clubhook squid, umbrella squid, reverse jewel squid and European flying squid, all identifiable from their indigestible beaks.[51] Ornithoteuthis volatilis, a common squid from the tropical Indo-Pacific, is predated by yellowfin tuna, longnose lancetfish, common dolphinfish and swordfish, the tiger shark, the scalloped hammerhead shark and the smooth hammerhead shark. Sperm whales also hunt this species extensively as does the brown fur seal.[52] In the Southern Ocean, penguins and wandering albatrosses are major predators of Gonatus antarcticus.[53]

Giant squid have featured as monsters of the deep since classical times. Giant squid were described by Aristotle (4th century BC) in his History of Animals[54] and Pliny the Elder (1st century AD) in his Natural History.[55][56] The Gorgon of Greek mythology may have been inspired by squid or octopus, the animal itself representing the severed head of Medusa, the beak as the protruding tongue and fangs, and its tentacles as the snakes.[57] The six-headed sea monster of the Odyssey, Scylla, may have had a similar origin. The Nordic legend of the kraken may also have derived from sightings of large cephalopods.[58]

In literature, H. G. Wells' short story "The Sea Raiders" featured a man-eating squid species Haploteuthis ferox.[59] The science fiction writer Jules Verne told a tale of a kraken-like monster in his 1870 novel Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea.[58]

Squid form a major food resource and are used in cuisines around the world, notably in Japan where it is eaten as ika sōmen, sliced into vermicelli-like strips; as sashimi; and as tempura.[60] Three species of Loligo are used in large quantities, L. vulgaris in the Mediterranean (known as Calamar in Spanish, Calamaro in Italian); L. forbesii in the Northeast Atlantic; and L. pealei on the American East Coast.[60] Among the Ommastrephidae, Todarodes pacificus is the main commercial species, harvested in large quantities across the North Pacific in Canada, Japan and China.[60]

In English-speaking countries, squid as food is often called calamari, adopted from Italian into English in the 17th century.[61] Squid are found abundantly in certain areas, and provide large catches for fisheries. The body can be stuffed whole, cut into flat pieces, or sliced into rings. The arms, tentacles, and ink are also edible; the only parts not eaten are the beak and gladius (pen). Squid is a good food source for zinc and manganese, and high in copper,[62] selenium, vitamin B12, and riboflavin.[63]

According to the FAO, the cephalopod catch for 2002 was 3,173,272 tonnes (6.995867×109 lb). Of this, 2,189,206 tonnes, or 75.8 percent, was squid.[64] The following table lists squid species fishery catches that exceeded 10,000 tonnes (22,000,000 lb) in 2002.

Prototype chromatophores that mimic the squid's adaptive camouflage have been made by Bristol University researchers using an electroactive dielectric elastomer, a flexible "smart" material that changes its colour and texture in response to electrical signals. The researchers state that their goal is to create an artificial skin that provides rapid active camouflage.[65]

The squid giant axon inspired Otto Schmitt to develop a comparator circuit with hysteresis now called the Schmitt trigger, replicating the axon's propagation of nerve impulses.[66]

(Did I just paste the entire Wikipedia article on squids here? Yes. Do I know why? No.)

0 notes

Text

I have nothing against USA, but they have tried to extinguish Animalia Bilateria Cephalopoda Coleoidea Sepiolida Vermiformidae Caederus Americana, and that's a crime.

0 notes

Text

Also thank you for 250 kudos and over 7k views for Oh. It’s Them Again 😊

Seeing my most fun Percabeth fic to date be so interesting warms my heart 🫶🏾

If I’m not back with Coleoidea, I’ll certainly be back with 1-2 one shots this year (A Click Apart and/or The Mamas and the Papas)

#pjo#oh. it’s them again#percy jackson#annabeth chase#Percabeth#a Click apart#coleoidea#the mamas and the papas#mel rambles#over and out

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

#squid #mollusc #Decapodiformes #Coleoidea.

https://etsy.me/2PwMIZP

0 notes

Text

Mimic octopus (Thaumoctopus mimicus)

Photo by Marcel Gierth

#id'ing#mimic octopus#thaumoctopus mimicus#thaumoctopus#octopodidae#octopodoidea#incirrata#octopoda#octopodiformes#coleoidea#cephalopoda#conchifera#mollusca

164 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cruz Erdmann was on an organised night dive in the Lembeh strait off North Sulawesi, Indonesia. It was here where he encountered the pair of bigfin reef squid. They were engaged in courtship, involving a glowing, fast‑changing communication of lines, spots and stripes of varying shades and colours. One immediately jetted away, but the other – probably the male – hovered just long enough for Cruz to capture one instant of its glowing underwater show

Photograph: Cruz Erdmann/2019 Wildlife Photographer of the Year

(via Wildlife photographer of the year 2019 winners – in pictures | Environment | The Guardian)

#Bigfin Reef Squid#Sepioteuthis lessoniana#Sepioteuthis#Loliginidae#Myopsida#Decapodiformes#Coleoidea#Cephalopoda#Mollusca#squid#marine life#ocean#Indonesia

32 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Given its transparent body, the glass octopus (Vitreledonella richardi) remains one of the most elusive creatures of the deep sea. Rare photographs such as this reveal an array of opaque organs and a glimpse of its unusually shaped eyes. Scientists think the upward tilt and elongation of its rectangular eyes are adaptations to help the glass octopus avoid predation.

Photo: Solvin Zankl

#Animal#Invertebrate#Mollusk#Cephalopod#Octopus#Lophotrochozoa#Coleoidea#Neocoleoidea#Octopodiformes#Octopoda#Incirrina#Octopodoidea#Amphitretidae#Vitreledonellinae#Vitreledonella#Vitreledonella richardi#Glass Octopus

129 notes

·

View notes

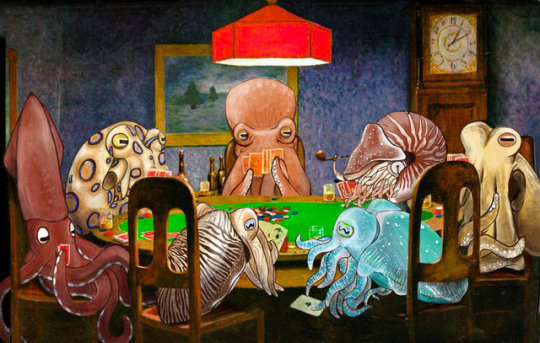

Photo

#cephalopod#tacky#painting#tentacles#art#poker#squid#cuttlefish#octopus#nautilus#coleoidea#gambling#lol

631 notes

·

View notes

Link

This is a playlist containing 4 of my recent videos on octopuses’ circulatory systems and related topics. Hope you guys enjoy!

0 notes