#ca. 400 b.c

Text

~ Brazier in the Form of the Old God.

Place of origin: Teotihuacan, Mexico

Period: Early Classic period (250 B.C.–A.D. 600)

Date: ca. A.D. 400–500

Medium: Basalt

#ancient#ancient art#history#museum#archeology#ancient sculpture#ancient history#5th century#6th century#Teotihuacan#mexico#mesoamerica#early classic period#basalt#a.d. 400#a.d. 500

609 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Embroidered textile feline, Nazca, ca. 200 B.C.–A.D. 400, camelid fiber

Princeton University Art Museum, New Jersey

701 notes

·

View notes

Text

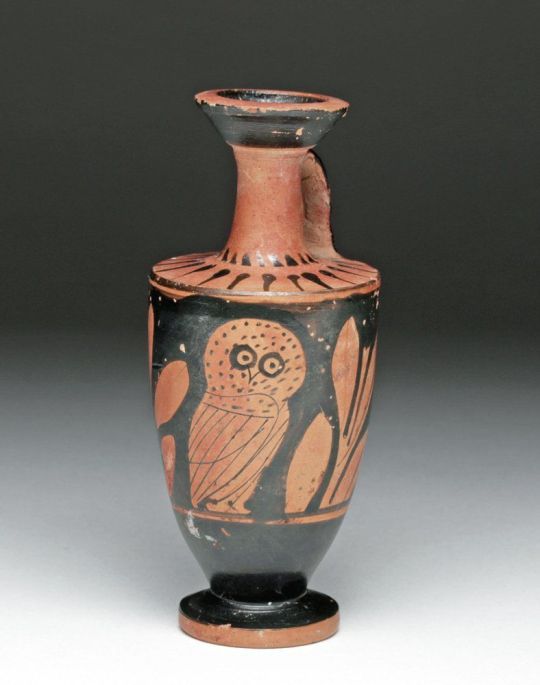

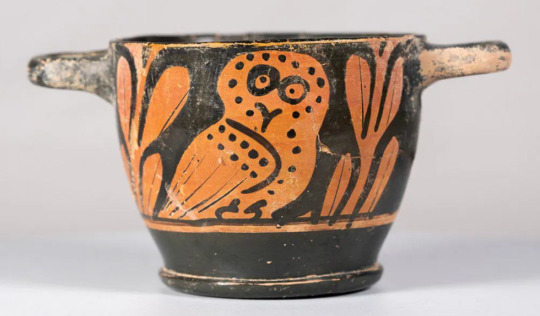

Greek Attic Red-Figure Owl Lekythos, Athens, Greece, second quarter 5th century B.C.

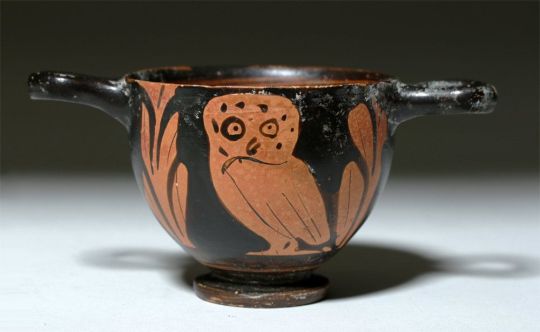

Greek Attic Red-Figure Owl Skyphos, Ancient Greece, Late Attic, ca. 370 to 350 B.C.

Skyphos. Ancient Greece, Attic, circa 400 B.C.

Greek Attic Red-Figure Owl Skyphos, Ancient Greece, Athens, ca. late 5th century B.C.

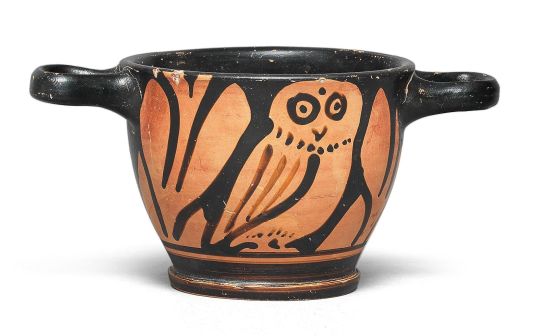

Greek Apulian Red Figure Ware Owl Skyphos, c. 5th-4th Century B.C.

Greek Red-Figure owl skyphos, Magnia Graecia, mid-4th Century B.C.

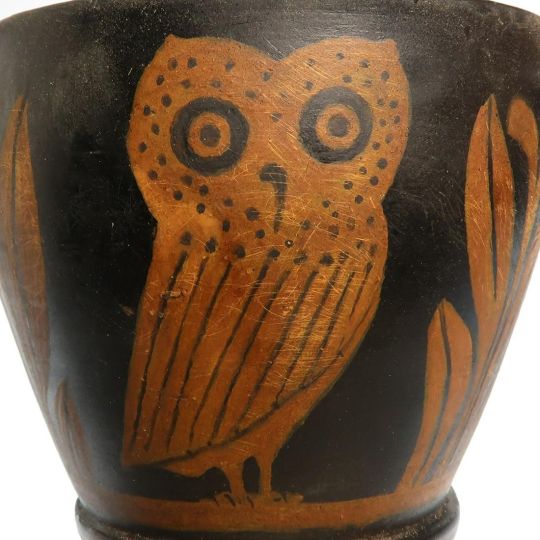

Skypos, Ancient Greece, Athens, Attic, ca. mid-5th century B.C.

#ceramics#ancient greece#i thiiiiink i put all of the links in the right order but i'm not 100% sure. they are the correct links tho#owls#athens#(mostly)#lekythos#skypos#red-figure ware

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

2500-Year-Old Bronze Age Artifacts Found in Poland

A metal detectorist looking for a World War I artifacts near Turobin, eastern Poland, found a hoard of Bronze Age jewelry instead. They were produced by the Lusatian culture in the waning era of their dominance in the region, ca. 550-400 B.C. Lusatian artifacts are extremely rare finds in this part of Poland, and the ones that have been discovered are usually individual pieces or fragments.

Łukasz Jabłoński, armed with a permit from the Provincial Office for the Protection of Monuments in Lublin, scanned the field on January 21, 2023. Digging under the snow, he found 13 bronze artifacts 8-10 inches under the surface of the soil. He immediately reported his discovery to the conservation office in Zamość and turned in the objects.

The 13 pieces include a cloak pin 6 inches long with a large spiral twisted wire terminal 2.8 inches in diameter. The pointed tip of the pin is missing. A second pin is even longer — 6.5 inches — and is intact with its pointed end. The head is a smaller spiral 1.2 inches in diameter with a decorative knob in the center.

Another stand-out piece is a twisted neck torc in penannular shape made from a single piece of bronze wire with tapered ends. The twisting technique was an advanced metalworking skill, especially using bronze because it hardens quickly and must be annealed repeatedly during the twisting process to prevent it from breaking.

There are also eight bracelets in the group: two 4.7 inches in diameter made of thick bronze wire with blunt overlapping ends, two made of single-stranded flat wire (one undecorated, the other incised with herringbone lines), and four massive ones three inches in diameter with overlapping ends.

The hoard is now being conserved and studied at the Museum of the Biłgoraj Land in Biłgoraj. The location of the find site has been kept secret to deter looters while archaeologists excavate it to find out more about the deposit and to look for any additional artifacts that might be in the area.

#A 2500-Year-Old Bronze Artifacts Found in Poland#Turobin Poland#metal detector#metal detecting#metal detecting finds#bronze#bronze artifacts#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient hiatory#ancient culture#ancient civilizations

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Aphrodite of Knidos, Greco-Roman variant on the original marble of ca. 350 B.C. Created, Greece, ca. 400 B.C. Sculptor, Praxiteles.

"While best known as Aphrodite, goddess of love, she was the ancient Greek goddess of love, beauty, fertility, physical pleasure (particularly sexual), eternal youth, grace, and beauty. Additionally, she played roles in commerce, war, and politics, and perhaps most notably, as one of the progenitors of the Trojan War." - Study

120 notes

·

View notes

Text

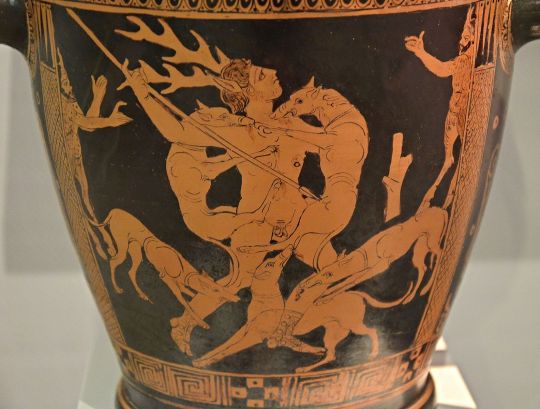

a vase depicting the myth of actaeon from c. 400-350 B.C from the collections of germany's baden state museum // pennsylvania furnace by lingua ignota

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

~ Lucanian Calyx-Krater, ca. 400 B.C.

via theancientwayoflife

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

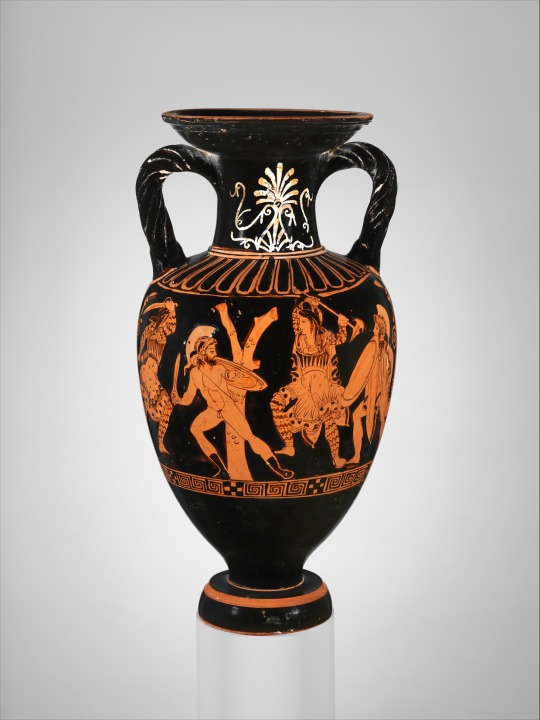

Terracotta neck-amphora (jar) with twisted handles. ca. 400 B.C.. Credit line: Fletcher Fund, 1944 https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/254518

#aesthetic#art#abstract art#art museum#art history#The Metropolitan Museum of Art#museum#museum photography#museum aesthetic#dark academia

1 note

·

View note

Text

Alexander the Great's surprising battlefield decision proved pivotal for facial hair norms that lasted hundreds of years. Photograph By Bridgeman Images

Beards and Mustaches Have a Weirder History Than You Think

No-Shave November may be a modern phenomenon. But our love-hate relationship with beards and mustaches dates back to the days of Alexander the Great.

— By Dina Fine Maron | November 7, 2023

More than 2,000 years ago, as Alexander the Great’s troops prepared for a pivotal battle over Asia, the famous Macedonian commander learned that his troops were outnumbered by at least five to one. To help assuage some of his force’s anxiety, Alexander issued an unusual order—his troops needed to shave. Why? It was too easy, he said, for their foes to grab Macedonian beards.

The move, coupled with Alexander’s surprising success on the battlefield, fueled a trend in beardlessness among Greek and Roman men that endured for the next 400 years, according to historian Christopher Oldstone-Moore, who wrote the 2015 book Of Beards and Men: the Revealing History of Facial Hair.

This tweezer-razor made of bronze or copper alloy and crafted more than 3,000 years ago in Egypt, was found in a coffin in the tomb of Neferkhawet, a scribe who lived around 1500 B.C.

The razor of Amenemhat, the father of Neferkhawet, made of similar materials, was found in the same tomb in the mid-1930s. Photographs By The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1935

Alexander’s wartime decision was really a turning point for facial hair, says Oldstone-Moore, who is himself currently clean-shaven. “The history of men is literally written on their faces,” he writes in his book. Indeed, long before modern movements like No-Shave November or Movember were founded to raise awareness for cancer research and other causes, trends in men’s facial hair have waxed and waned alongside the societal significance of being clean-shaven, whiskered, or mustachioed. Men’s personal grooming, according to historical books and peer-reviewed studies, extends across art, politics, and even into the court room. Much of that work to date focuses on European and American trends, though beard choices have long been meaningful to communities and religions around the world, signaling, among other things, religious piety for Muslims and Jews.

Shaving facial hair dates as far back as the Sumerians and Egyptians, who used razors made of copper or bronze. Generally, however, most men in ancient times favored beards and it was considered arduous and sometimes also unsafe to shave. Still, for most men it wasn’t about being “too lazy to shave,” either then or now, says Oldstone-Moore, an emeritus lecturer at Wright State University, in Ohio. “Fashionable men would still have to go to barbers and have their beards cared for properly, and they’d have oils and combs and that sort of thing.”

The Regal Power of Facial Hair

Facial hair has often been equated with masculinity and related patriarchal power, but that hirsute power is sometimes transferrable: Notably, Pharaoh Hatshepsut (ca 1508– 1458 B.C.) donned an artificial beard when she ruled Egypt for more than two decades. Egyptian kings had previously fashioned themselves in stylized ways, with wigs and crowns and artificial decorative beards, Oldstone-Moore notes, so Hatshepsut’s beard was aligned with her predecessors’ sartorial customs.

Hatshepsut (ca 1508– 1458 B.C.) wore an artificial beard when she ruled Egypt, but her male predecessors had already normalized wearing decorative beards. Photograph By Rogers Fund, 1931, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Beards were later of such import that Shakespeare explicitly mentions them in all but four of his plays, notes historian Will Fisher in the journal Renaissance Quarterly in 2001. Moreover, he writes, analysis of a collection of about 300 portraits of European men from the 1500s and 1600s indicates that for every portrait of a man without a beard, there were about 10 portraits of men with beards. Styles of the time included the thin, angular “stiletto,” a fuller “square cut,” and even a double-tufted “swallowtail.”

Can Facial Hair Make You Sick?

Ideas about the significance of men’s beards have made it into medical books. Growth of facial hair, Renaissance physicians wrote, was explicitly tied to the production of semen, an idea presaged by classical Greek scientists who theorized that men have “vital heat” which explains their size, strength, and hairiness. According to this false theory, both sexes produce this vital heat, which then gives rise to semen, yet women’s bodies aren’t equipped to handle significant amounts of it.

By this way of thinking, Oldstone-Moore writes, only a man’s body could survive growing a beard. In classical Greece, people believed if a post-menopausal woman grew some facial hair, sickened, and eventually died, she simply had an unnatural buildup of semen, and facial hair was a symptom of that underlying issue.

Adding another layer to that theory, German abbess Hildegard of Bingen, around the year 1160, offered that the reason facial hair occurred exclusively around the mouth—rather than, say, on the forehead—was because of men’s hot breath. Women, according to Hildegard’s writings, wouldn’t have breath that was as hot as a man’s because men were formed from the “earth,” whereas females were formed from men, she then explained, tying her thinking back to creation ideology.

By the 1700s, when shaving once again became de rigeur and it was considered respectable and gentlemanly to shave, the phrase “clean-shaven” took hold. In the nineteenth century, Louis Pasteur’s germ theory also further shored up medical support for shaving: Facial hair, doctors warned, was a microbe haven. Indeed, one French scientist noted in a 1907 experiment that the lips of a woman kissed by a mustached man were “polluted with tuberculosis and diphtheria bacteria, as well as food particles and a hair from a spider’s leg.” A study in the Lancet around that same time also concluded that shaven men were less likely to develop colds. The work argued that soap could be more effective on a hairless face, according to Oldstone-Moore.

King C. Gillette patented his famous safety razor in the U.S. in 1904. Employers at the turn of the century expected their workers to be clean-shaven. Photograph By Bettmann, Getty Images

This Gillette safety razor, photographed with its original box, was from the 1930s, when shaving cream and equipment fueled millions of dollars in sales in the United States annually. Photograph By Science & Society Picture Library , Getty Images

Workplace Norms and Controversies

Workplaces in the early 1900s and onward also regulated facial hair and instituted requirements for its male workforce to shave as a key sign of professionalism and cleanliness. Relatedly, in 1904, King C. Gillette patented his safety razor in the U.S. and by 1937, Oldstone-Moore writes, shaving cream and related accessories had estimated sales of $80 million in the U.S. alone. (Related: See these world beard and mustache champion photos.)

Facial hair controversies also rose to the highest court in the land: A U.S. Supreme Court case in 1976, Kelley v. Johnson, even upheld an employers’ authority to dictate grooming standards for their employees. In that case, policemen of Suffolk County, New York, had taken issue with workplace standards that barred them from growing hair below their collars or facial hair except for a neatly trimmed mustache that didn’t extend onto the lip. The county successfully argued that these grooming regulations made police recognizable to the public and contributed to the cohesiveness of the force. In the years that followed, that case precedent was further applied to school employees and other workers across the country.

More than a dozen years after the Supreme Court ruling, in 1992, Massachusetts police officers pushed back against a statewide ban on facial hair among its officers. They, too, lost.

In more recent years, however, despite those standing court rulings, western facial hair norms have shifted, and employers have largely pulled back from stringent regulations, at least informally.

“Beards or facial hair of some sort often come back when gender or masculinity are being somehow debated,” says Alun Withey, a historian at the U.K.’s University of Exeter and author of the 2021 book Concerning Beards: Facial Hair, Health and Practice in Britain, 1650-1900. “Today there are multiple debates and challenges surrounding concepts of gender and the body, so perhaps the recent beard trends in part reflect this,” he says.

With increased facial freedom, a variety of personal grooming choices have now taken hold. But purveyors of men’s shaving and personal grooming equipment are not hurting—market analysis from June 2022 indicates that instead of razors, men are now instead investing more in electric trimmers.

0 notes

Video

youtube

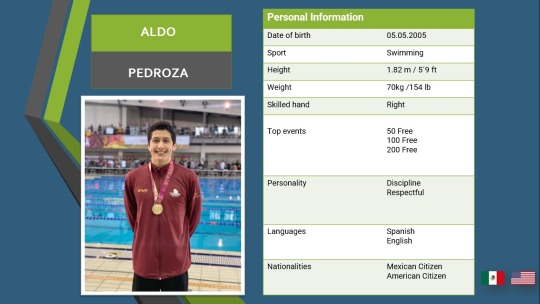

Aldo Pedroza - Men´s Swimming - Mexico - 2024

NOTE: Aldo has american citizenship

Athletic Career

2022 JUN. CONADE NATIONAL GAMES 2022 Tijuana, B.C.

-1st 100 Free (53.14)

-1st 50 Free (24.41)

-2nd 200 Free (1:56.03)

-2nd 4x100 (52.22)

-2nd 4x200 (1:55.44)

2022 APR. CANCUN UNIQUE SELECTIVE 2022

-1st 50 Free (24.81)

-2nd 200 Free (1:56.60)

-3rd 100 Free (53.23)

2022 MAR. GRAND PRIX JR, CANCÚN QROO

-1st 50 Free (24.61)

-1st 100 Free (54.03)

-1st 200 Free (1:57.91)

-2nd 400 Free (4:15.11)

2021 DIC. NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIP SC PRIMERA FUERZA, Guadalajara JAL.

-Final A 8th 50 Free (23.66)

-Final B 2nd 100 Free (51.93)

-Final B 2nd 200 Free (1:54.71)

2021 JUN CONADE NATIONAL GAMES, Monterrey NL

-1st 50 Free (24.92)

-2nd 100 Free (54.13)

-2nd 200 Free (1:59.45)

-1st 4x100 Free Relays

-2nd 4x200 Free Relays

Swimming meets in the US

SI CSA President´s Day Senior Meet (2023)

50 Y Free Finals - 23.32

50 Y Free Prelims -23.14

50 Y Free Finals - 22.40- 17th

50 Y Free Prelims - 22.21- 19th

100 Y Free Finals - 48.26- 15th

100 Y Free Prelims - 48.43- 18th

200 Y Free Finals - 1:44.82- 12th

200 Y Free Prelims - 1:46.67 - 21st

Far Western LC Championships (2022)

50 L Free Finals- 25.08- 8th

50 L Free Prelims- 25.07- 6th

100 L Free Finals - 53.99 - 4th

100 L Free Prelims - 55.29 - 9th

200 L Free Prelims - 2:02.74 - 13th

CA RMDA La Mirada June Invite (2019)

50 L Free Finals - 25.94 - 2nd

50 L Free Prelims - 26.29 - 3rd

100 L Free Finals - 57.56 - 6th

100 L Free Prelims - 58.00 - 5th

200 L Free Finals - 2:04.75 - 3rd

200 L Free Prelims - 2:06.77 - 3rd

400 L Free Finals - 4:27.02 - 5th

400 L Free Prelims - 4:30.22 - 8th

100 L Back Finals - 1:07.65 - 9th

100 L Back Prelims - 1:10.76 - 9th

200 L IM Finals - 2:25.72 - 12th

200 L IM Prelims - 2:26.43 - 10th

CA ORCA SCY H/F SUMMER SIZZLER (2018)

50 Y Free Finals - 24.47 - 2nd

50 Y Free Prelims - 24.92 - 2nd

100 Y Free Prelims - 56.14

100 Y Back Prelims - 1:07.21

100 Y Fly Finals - 1:03.72 - 6th

100 Y Fly Prelims - 1:02.36 - 3rd

200 Y IM Finals - 2:16.41 - 5th

200 Y IM Prelims - 2:20.02 - 7th

400 Y IM Finals - 4:58.28 - 5th

400 Y IM Prelims - 5:01.50 - 5th

Swimcloud Profile

https://www.swimcloud.com/swimmer/1395929/

He would like to major in:

1.- Business Administration

2.- Marketing

3.- Supply Chain Management

Contact information:

+52 686 307 97 29

0 notes

Text

~ Stater of Kroton with head of Hera Lakinia.

Culture: Greek

Period: Classical Period

Date: ca. 400–325 B.C.

Mint: Bruttium, Kroton

Medium: Silver

#ancient#ancient art#history#museum#archeology#numismatic#numismatics#coin#money#currency#ancient currency#stater#kroton#hera lakinia#greek#classical#bruttium#silver#ca. 400 b.c.#ca. 325 b.c.

333 notes

·

View notes

Text

Terracotta head of a woman wearing a stephane

ca. 400–310 B.C.

Cypriot

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

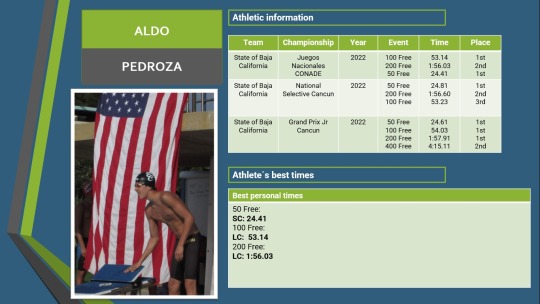

The Mycenaean Warrior Vase 12th C. BCE

"In one of the buildings closest to Circle A (Fig. 1, F), Schliemann discovered the fragments of a large, decorative ceramic bowl, used for mixing water and wine. Because of its friezes of soldiers, he dubbed it “the Warrior Vase.” It is probably the best known piece of Late Helladic pottery (Figs. 3, 5A).

For quite some time after its discovery, scholars dated the bowl to the seventh century B.C. They regarded its peculiar bull’s head handles as definitely derived from those found on eighth-century vases.(1) They likewise considered the registers of spearmen as a development from the eighth-century processional friezes on funerary jars found near the Dipylon Gate at the Kerameikos cemetery of Athens. They unhesitatingly attributed the soldiers on the bowl to the Protoattic Period (i.e., early seventh century B.C.) on the basis of style, comparing them to the warriors on another mixing bowl (Fig. 4) painted by a known seventh-century artist; some even ascribed both bowls to the same man. (2) They felt that still other technical and stylistic features of the bowl and its decoration indicated a date between 700 and 650 B.C. for the Warrior Vase.(3) That same vase is now firmly assigned to the early LH III C period, which Egyptian chronology fixes at ca. 1200 B.C.,(4) leaving as problems the peculiar handles and the figural style. Over seventy years ago, D. Mackenzie replied to those who derived its bull’s head handles from eighth-century prototypes, that the Warrior Vase itself proved that such a device “had a much earlier history.” (5) Still, they stood in isolation from the much later handles, originally thought to be their prototype. The more recent discoveries of two other LH III C handles of the same type(6) has provided companion pieces, but has not alleviated the problem.

The spearmen of the Warrior Vase not only resemble the men depicted on seventh-century Protoattic Pottery from Greece, but, as L. Woolley justly noted, they also look “remarkably” similar to soldiers painted on terracotta roof tiles from Phrygia in Asia Minor, currently dated sometime between the late eighth century and the sixth (fig. 6)(18) Regarding Greek art, “one might almost say that the decorators of Protoattic pottery took up the animal [and human] designs where their predecessors of late Mycenaean times had left off. The similarity is very striking.” (19) With 400 years separating the end of one from the beginning of the other, without anything comparable between the two, “the similarity is very striking” indeed!"

-taken from varchive.org

https://paganimagevault.blogspot.com/2020/02/the-mycenaean-warrior-vase-12th-c-bce.html

#mycenaean#ancient greece#greek#antiquities#europe#pagan#european art#classical art#art history#classic art#paganism#12th century bce

107 notes

·

View notes

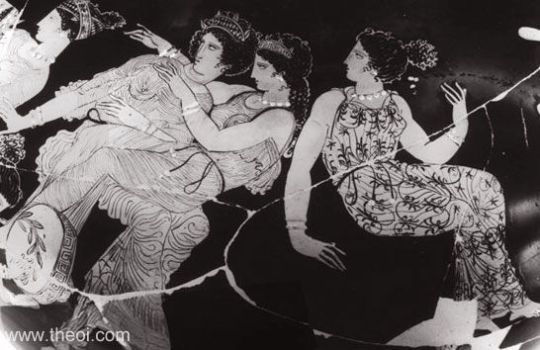

Text

National Archaeological Museum of Florence

Catalogue No.Florence 81948 Beazley Archive No.220493

The Three Graces

Ware Attic Red Figure

Shape Hydria

Painter Attributed to Meidias Painter

Date ca 450 - 400 B.C.

Period Classical

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Chimaera of Arezzo (Italian, #Etruscan, ca. 400 B.C.). Arezzo. Bronze. H. 31 1/2 in. Museo Archaeologico Nazionale di #Firenze, #Florence, #Italy. https://www.instagram.com/p/B4-Y2wTlTgV/?igshid=fzfzrtpqpy6h

54 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sacred animal mummy of a cat

ca. 400 B.C.–100 A.D.

The Met

70 notes

·

View notes