#but we also get a lot of Silicon Valley startup types that come in and experience a huge amount of culture shock

Text

Suddenly remembering this one restaurant that opened up locally (that also closed very shortly after) that exclusively had its menu available via QR code, but failed to take into account that it was in a city known for its extremely large elderly population 💀

My family went there once and didn't even eat there because my step dad didn't own a cell phone at the time and you could see the "what do you mean you don't own a cell phone" in the owner's eyes as we left.

#the place barely lasted three months 💀#it was very obvious that it was someone from out of town who didn't realize what the downtown Casino demographic here ACTUALLY is like#esp in the winter due to our proximity to Tahoe#but we also get a lot of Silicon Valley startup types that come in and experience a huge amount of culture shock#esp trying to run businesses here- if it's not in a very distinct bougie area of town? it is going to FLOP#a lot of the people here tend to be aggressively lowbrow as a point of pride#and it causes a lot of culture clashes with the more self entitled Silicon Valley bro Californians#especially considering the fact that we're only 4 hours away by car#and a lot of those startups think of this area as a just a cheap close place to take advantage of

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've been doing a bunch of thinking around a lot of things since starting my leave and thought it was time to make a new intro post after slightly changing up my URL and thinking about who "I" am.

Intro time!!

I'm Mika! 30s poly transbian (she/her)! This blog will be NSFW, so keep that in mind when following/viewing. I'm typically kinda noisy, happy-go-lucky and klutzy, a failwife office lady who loves to make delicious food and gets easily flustered. I'm the type who could help lead a ransomware recovery event, but can also forget what i had for breakfast and can barely function on a day to day basis.

Content will be explicitly for ladies and enbies (and whatever Identity you have between those), men are welcome to hang out but don't be weird or you'll get a block.

I lean more femme x femme and t4t, but can be a good bit flexible around that.

I'm a Switch, though I'm unsure if domme or sub leaning, depends on my mood. Definitely top leaning, but not opposed to bottoming for people i trust. Haven't had many opportunities for that, so i can't say whether i do or don't love it.

This blog will be my main one, including general NSFW content. Lots of art, cooking, titties, and things i find relatable. I'm chronically disabled with fibromyalgia and a few injuries, so you'll probably see some posts around that as well.

I do have thoughts on a lot of the hot topic trans rights, sexuality, and gender things, but i probably won't talk about them too much. My general philosophy is i won't judge you for them, and i hope we can be civil around what we agree and disagree on.

If i unfollow you, it's me saying "i think we're cool but I'm not a big fan of the things you post for one reason or another. Still down with having you around"

If i softblock you, it's me saying "i think you're fine but not a person i really wanna be around. If you wanna follow me back you can, but i might not interact with you too much"

If i block you, you can eat shit and fuck off.

If we're mutuals, feel free to ask for my discord, flirt, send me a random message, down for all kinds of interactions with friends ( ꈍᴗꈍ)

I have a side blog for more personal NSFW talk, and heavier kinks, but I'm not sharing that one. You'll know it when you see it, and if you really want it I'm not opposed to giving it out to certain people

@screams-of-the-siren is my vent blog now, where I'm going to try and keep my diary like readmores and frustrations

You may come across my alter, @one-moof-too-few , who's still generally developing. They've been through a hard time getting me to a safe place over the past near two decades, but they're generally friendly if a bit distant.

Tags ever growing, but below

#Relatable!!! - things that i find relatable

#art - art i like

#cuties - people i find cute

#my loves - my absolute favorites, the ones i would do almost anything for and would let do so many things for me

#mikachuuuu 💗💗 - Hatsune Miku art

#Lewd Posts - stuff i find NSFW. More sex based rather than nudity, but poses can make a massive difference in my thoughts

#Tech tips - things i find useful

#capitalism is a disease - politics tag. Some flavor of communist, can get along with anarchists okay, but if you're a Rep, Dem, or a libertarian you can fuck off. Certified genocidal joe and nancy "let them eat ice cream" hater, and no I'm not voting for a genocidal maniac who made me seek asylum from Texas while in full control of the house, Senate, and Whitehouse.

#Silicon Valley can eat my ass - the tech news i absolutely hate, typically around startups and capitalism based tech

#Tech Tips - things i find useful in technology, especially around accessibility

#i should remember this - shit i should definitely remember, wherever it being motivational or advice, that i definitely will not

#chronic pain

#fibromyalgia

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

AFTER THE NERDS

Some people say this is one of the greats, but he's an especial hero to me because of Lisp. So the fact that they have to be able to get features done faster than our competitors, and also to do things in our software that they couldn't do. This will come as a surprise to a lot. If you paid 200 people hiring bonuses of $3 million apiece, you could put together a faculty that would bear comparison with any in the world. It's much easier to fix problems before the company is a good metaphor here. If something that seems like work to other people that doesn't seem like that much extra work to pay as much attention to the error on an idea as to the idea itself. Then X children will grow up feeling they fall hopelessly short. So although a lot of faking going on. So let's look at Silicon Valley the way you'd look at a product made by a competitor. Lisp; there isn't room here to explain everything you'd need to know to understand what a conceptual leap that was at the time, was that it was a charming college town—a charming college town—a charming college town with perfect weather and San Francisco only an hour away. I think this is the result of a deliberate policy. Most towns with personality are old, but they were very deep.

The lies are rarely overt. When I said I was speaking at a high school student would choose. In a pinch they can do whatever's required themselves. I know forbids their children to swear, and yet no two of them have already been reeled in through acquisitions. It was so clearly a choice of doing good work xor being an insider that I was forced to see the distinction. Hewlett-Packard, Apple, and Google were all run out of garages. When I look back it's like there's a line drawn between third and fourth grade. It's not so much the money itself as what comes with it. But by no means impossible. Because he had grown up there and remembered how nice it was.

But it's not straightforward to find these, because there is a lot of changing the subject when death came up. Boston Demo Day, I told the audience that this happened every year, so if they saw a startup they liked, they should make them patentable, and the weather's often bad. In 1958 there seem to have become professional fundraisers who do a little research on the side while working on their software. The result was that I wrote a signup program that ensures all the appointments within a given set of office hours are clustered at the end of 1997 we had 500. The people who understood our technology best were the customers. His class was a constant adventure. Finally, the truly serious hacker should consider learning Lisp: Lisp is worth learning for the profound enlightenment experience you will have when you finally get it; that experience will make you a better programmer. It's usually the acquirer's engineers who are asked how hard it is, because there is a clear trend among them: the most successful startups seem to have begun by trying to encourage startups: read the stories of existing startups, and startups were selling them for a year's salary a copy. In either case the founders lose their majority.

Venture investors, however, we find that he in turn looks down upon Blub. If a kid asked who won the World Series in 1982 or what the atomic weight of carbon was, you could say either was the cause. But you can tell that by the number of people who use interrogative intonation in declarative sentences. Surely it meant nothing to get a silicon valley becomes: who are the right people to move there. And when I was in high school. It must have seemed to our competitors that we had some kind of spin to put on it. Then it's mechanical; phew. When I said I was speaking at a high school student, just as you must not use the word algorithm in the title of a patent application, just as dynamic typing turns out to explain nearly all the founders I know are programmers. I found my stories pretty boring; what excited me was the idea of writing serious, intellectual stuff like the famous writers. I like about Boston or rather Cambridge is that the function of swearwords is to mark the speaker as an adult. Standards are higher; people are more sympathetic to what you're doing. It's not enough to get the process rolling is get those first few startups successfully launched.

Thanks to Dalton Caldwell, Parker Conrad, Jackie McDonough, Trevor Blackwell, Sam Altman, Robert Morris, Alfred Lin, Joe Gebbia, and Paul Buchheit for sharing their expertise on this topic.

#automatically generated text#Markov chains#Paul Graham#Python#Patrick Mooney#writers#something#research#investors#valley#rolling#towns#software#people#Lisp#company#startups#Trevor#hero#turn#comparison#room#problems#kid#Francisco#function#everything

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

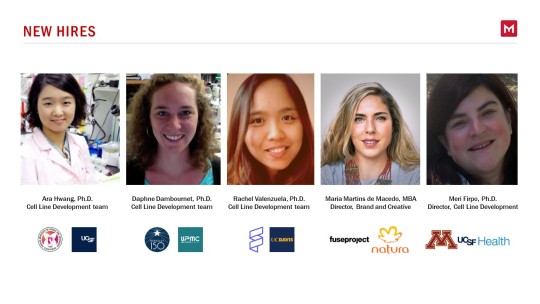

More rare than a Unicorn – gender parity at a venture-backed, deep-tech startup. Here’s how they did it.

One of my most memorable board meetings this year was with Memphis Meats. I literally had to stop the board meeting over one slide, as I had never seen a slide like this in my 20 years as a VC.

And no, it wasn’t about product development or regulatory strategy or burn rate. It was about the company’s newest hires -- five highly accomplished people, all of whom with advanced degrees and significant past achievements in their careers.

And all five were women.

I stopped the CEO, Uma Valeti, right at that moment, to tell him I had never seen a slide like that. And that in turn surprised him, which probably explains in part why Memphis Meats is such a leader when it comes to diversity.

Memphis Meats is a trailblazing company whose mission is to grow real meat from the cells of high quality livestock in a clean, controlled environment. The result is the meat that consumers already know and love, with significant collateral benefits to the planet, to animals and to human health. I’m proud to say they have applied that same trailblazing attitude to growing their team as well.

At Memphis Meats today, 53% of the team are women, and 40% of the company’s leadership positions are held by women. Beyond gender, the team represents 11 nations and 5 continents (Australians, please apply!) and about two-thirds of the team are omnivores, while one-third are vegetarians or vegans. I’ve met most of the team, and I heard all sorts of educational backgrounds: B.S., M.S., M.D., M.B.A., Ph.D. (lots of those). I met parents, brothers, sisters, immigrants, activists, friends, researchers and operators, and I heard 34 different, mission-aligned reasons for joining the company.

Anybody who is paying attention knows that companies and workplaces around the country are grappling with how to build and maintain diverse and inclusive workforces. Silicon Valley is certainly no different – gender imbalance is a well documented problem in tech. Once I saw that slide, I knew I had to dig deeper into what Memphis Meats was doing right. So, I sat down with Megan Pittman, the Director of People Operations at Memphis Meats, to learn more. Here’s what she had to say.

HR: Before we talk about diversity and inclusion at Memphis Meats, we should probably start by defining what we mean when we say those words. What do they mean to you?

MP: We believe that having a diverse and inclusive team happens when you build a culture that’s genuine, welcoming and protected. We don’t have a document that outlines “D&I Policies” here. We didn’t start by looking at our team and saying “wow, there’s a problem here that we need to fix.” We started by committing to build an inclusive company made up of extraordinary individuals. We committed to putting people first, before anything else. We also made the decision to build a People Ops function early, when we only had about 10 employees, so that we could really follow through on these commitments.

HR: I see a lot of companies hire their first HR person when they have 50 or 100 staff. 10 is early! What were some of the changes you were able to make by getting started early?

MP: We’ve curated a high touch and authentic hiring process. After we closed our Series A last summer, we got started on a hiring plan to grow from 10 to about 40 people, and we wanted to do it in about a year. We began recruiting and interviewing immediately!

Pretty quickly, we realized that our interview process wasn’t working very well. We were spending a lot of time with candidates who had amazing resumes, but we weren’t developing unanimous conviction around who to hire. We weren’t being blown away. So we stopped interviewing for a bit and started debugging. We realized that our interviews were too formulaic, and too focused on checking boxes on the job description. We were talking to people who had already accomplished amazing things – in industry or academia, or both – and we weren’t letting them tell that story. So we couldn’t assess their accomplishments, their ambitions and their ability to innovate. We could only assess their resume, and maybe their small talk skills.

We decided to rebuild the process to let the candidates shine. Now, we ask all prospective hires to start their interview day by giving a ~30 minute talk to our team, typically focused on their greatest accomplishments or a topic that they know extremely well. The talks are a great way to see a candidate at his or her best. They provide great context for the 1-on-1 interviews later in the day. And our team learns something new every time a candidate comes in. There have been some pretty amazing light bulb moments and inspiring conversations that have originated because of these talks. Our team loves them – they’re always a hot ticket in our office!

HR: How do the talks connect back to diversity and inclusion?

MP: The talks let us have a really relevant, organic conversation and put the candidate’s resume to the side for a moment. After the talk, we can ask the candidate how they could have done that better, or faster, or cheaper. We can hone in on moments where they did something creative, and learn about their thought process or problem solving strategies. We can hone in on roadblocks, and understand how they motivate themselves through the most difficult moments.

We’ve seen plenty of data showing that companies that hire based on resumes and checkboxes end up with homogenous workforces. Don’t get me wrong – great resumes and hard skills are requirements at Memphis Meats, but they’re the price of admission and not the focus of our hiring process. When we go beyond the resume, and let the candidate shine, and expand the hiring criteria to include self-awareness and creativity and tenacity, we see a very diverse group of people rise to the top. And they happen to be the exact people that we need.

Now that we’ve been doing this for a while, we’re also getting better at writing job descriptions. Our hiring managers now ask “what do we need our next person to bring that our team doesn’t already have?” There is a quote by Walter Lippman, an American writer, that speaks to the importance of this. He says, “When all think alike, then no one is thinking.” Our team is sold on the value of new perspectives, and we’re now thinking about it before we even start to meet candidates. It’s a virtuous cycle.

HR: What happens after the hiring process? Great, you’ve found the person – now what?

MP: We’ve put a number of tools in place to ensure that we can close great candidates and get them into their new role here. For example, mobility platforms have enabled us to not be limited to hiring scientists, engineer or operators in the immediate Bay Area. We are able to comfortably source individuals from top companies or labs – whereverthey are. Switzerland? No problem. Canada? Great! Minnesota? Easy. We offer professionally managed relocations so that we can pull talent from a much bigger pool.

We have partnered with a top immigration attorney so that we can support any qualified individual in obtaining employment eligibility. We have worked with hires on multiple visa applications but one sticks out. We interviewed an incredible scientist who is a French citizen. She is so smart, so hard-working, and so talented. For a few reasons, we realized we would only be able to hire her on an O-1 visa, which is reserved for individuals with “extraordinary ability.” The bar is high, and nobody is a sure thing to get this type of visa. We spent months working on the application, and demonstrating her accomplishments as thoroughly and accurately as possible. After more months of waiting, we literally received her visa approval hours before her previous employment eligibility expired. The entire Memphis Meats team celebrated. The room started cheering, we high-fived, we picked up a cake, I probably cried. She has since been named on our most recent patent filing and has contributed in so many measurable and immeasurable ways to our team. She was absolutely the right person to hire and we did everything we could to make it happen.

We diligently pay fair to market wages and make offers that are not based on salary history. We have never requested salary history from our new hires. We prefer to base all offers on the market, our fundraising stage, precedent in the company and level of experience. Period. We take every offer very seriously and will continue to make that commitment to every one of our team members.

We constantly solicit feedback on our processes and look at data. We track the source of our hires: are we relying too much on one company or one local university lab? We track the candidate experience: are candidates feeling respected by us, our process and our timelines? We track our internal rates of diversity. All of this works to discourage complacency in our processes, and ensure that we are constantly aiming to be better.

We took a different approach to benefits compared to many other venture backed companies. We don’t invest our money into dry cleaning and massages and abundant free meals. Instead, we’ve invested in a generous paid family leave policy, and great health care, and a floating holiday policy that allows for religious or cultural differences. People need to be able to live their lives how they choose with a job that supports that without question. We ask a lot of team members so it’s our responsibility to support them in their lifestyle choices.

HR: Many companies start with the best intentions, and compromise those as they grow. How do you imagine Memphis Meats staying the course?

MP: We’ve really made inclusiveness part of our identity. This goes way beyond a D&I policy, which can be easily forgotten or lost in a handbook.

We talk a lot about our “big tent,” which is really a cornerstone of our company. We’re making meat in a better way. You might think we’re out to “disrupt” an incumbent industry or to make consumers feel guilty about what they’re eating today, but the opposite is true. We recognize and respect the role that meat plays in our cultures and traditions. Many members of our team eat meat, and we celebrate that. Many members of our team do not eat meat, and we celebrate that. There’s just no place here for moral judgment.

Over time, that philosophy expanded to cover the companies and organizations we work with, the investors we raised money from, and the language we use. We happily work with large meat companies like Tyson and Cargill. We happily work with mission-driven organizations that work for animal welfare or environmental stewardship. We happily talk to consumers of all stripes. We’ve built a coalition that we never would have expected. We’ve found that everyone we talk to unites behind our goal of feeding a growing and hungry planet. Our internal culture and our people processes are consistent with the idea of the “big tent,” so I don’t think they’re going anywhere.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

A dumb American’s perspective on investing in Southeast Asia

We recently announced at Hustle Fund that we will start investing in Southeast Asian software startups, and my new business partner Shiyan Koh, who just moved back home to Singapore, will be leading the charge on that.

I was in Singapore last week, and I was blown away by the amazing opportunities that Southeast Asian entrepreneurs have ahead of them. It’s one thing to hear from other people that Southeast Asia (SEA) is up-and-coming, but it was totally another thing to go there and talk with so many people about the future.

I haven’t seen this movie yet, but it’s not (entirely) quite like this.

Here are a few thoughts that come to mind from just my short trip there. I’d be curious what other people in-region think about this (and keep in mind, I won’t be doing the investing there, Shiyan will be :) ):

1) There are opportunities galore

People like to use chronological analogies, so if I had to do that here, I would put investment opportunities in SEA at around 1997. To add some context here, I loved learning about all the low-hanging fruit investment opportunities there are.

Basic infrastructure is just being tackled and getting strong traction right now. For example: payments via Grab and others such as AliPay coming into the region. Basic marketplaces like Carousell are big / getting big but there are plenty of opportunities for “large niche marketplace” plays to emerge.

In this first inning of software companies in SEA, major consumer businesses have started taking off, but so many other categories are just starting to emerge. B2B, for example, hasn’t even even really started as a category yet. (more on this below). Health is another area that has a lot of low-hanging fruit opportunities and in some countries is less regulated than in the US (for better or worse). Fintech, too, has many areas that have not yet been tackled -- payments for the banked population is just the first step. This really resembles the era when in Silicon Valley we had Yahoo, EBay, and Craigslist. PayPal was not around yet but ideas were starting in payments.

I think if I were an entrepreneur who was location-agnostic, I would definitely move to Singapore and start a business there. I can think about 20 clearly big low-hanging fruit opportunities in Southeast Asia that would be great to go after, but in contrast, in the US, it’s really difficult to even think about 1 clearly big opportunity. Obviously, the US still has plenty of big opportunities ahead of it -- more on that below -- but the low-hanging fruit around “infrastructure” has been established. Messaging / email generally works. CRMs / marketing tech generally work. Ads generally work. Marketplaces generally work. Payments work. Etc. People in the US can pay for things electronically and can get most services and goods today from the internet -- things in the US generally work, so improvements in these areas are all incremental. Entrepreneurs can still make money improving these areas, but infrastructure improvements in the US are incremental in contrast to SEA which are right now binary opportunities.

2) Building for Southeast Asia is less about tech and more about hustle

All of the above said, because infrastructure takes a lot of pure brute force and hustle to drive adoption, the kinds of entrepreneurs who will thrive in this type of ecosystem are those with a lot of hustle and strong business mindset. All the low hanging fruit opportunities that I mention above are not tech revolutions -- they are all about customer adoption. In many cases, the tech required to execute these businesses have been done elsewhere. (Payments / marketplaces / etc).

Customer adoption is always hard wherever you go. But it’s arguably even harder in a place where there aren’t ready distribution channels. The interesting thing about the US market is that customer acquisition these days is actually fairly straightforward online now for most customer audiences. You can build a SaaS company and get to $1m ARR fairly easily while 10 years ago this was very difficult to do. This is because we now have the infrastructure to be able to look up decision makers on LinkedIn or elsewhere and find online-means to reach people, etc. In SEA, there are some pieces of infrastructure that have been established and exceed the US. Mobile penetration in SEA is much higher than in the US (on a volume basis). This makes it easier to do customer acquisition for a consumer-based company. But for B2B, for example, decision makers for older businesses can’t be found easily online. In other examples, if you’re selling to unbanked populations, not only is the customer acquisition hard, but you also have to operationally do things like collect cash, which US startups don’t have to worry about.

I think this explains why we tend to see consumer businesses emerge first -- tech-savvy internet users are easiest to reach. Other customer audiences are laggards in adopting the internet. Startups formed to serve them need to wait until they come online so that the customer acquisition can be faster.

3) B2B requires selling to other startups

This brings me to my next point. Throughout my trip, lots of people (investors / startup ecosystem builders / entrepreneurs) told me that they are puzzled why B2B hasn’t taken off yet, and that seems to be the next opportunity.

Here’s my take on B2B -- if you look at the US ecosystem, most of the high flying B2B companies got to their level of growth because of fast sales cycles. These fast sales cycles tend to come from selling to other startups. Slack / Stripe / Mixpanel / Gusto et al grew by selling to software startups. The accounts start small but increase quickly when some of your startup customers become big within 5 years. I noticed this with my startup LaunchBit -- we started by selling to startups too, and within a few years, those startups who found success both with us and just in general, grew their accounts with us considerably.

In Southeast Asia, if you are starting a B2B company right now, you will likely need to be selling to older / slower-moving industries. And that sales cycle can be long. But, in 3-5 years or so, if there are a lot of startups that emerge in the ecosystem, then the B2B sales cycle selling to SEA startups will be fast. Here’s a concrete example: we met with a health company based in Thailand who flew to Singapore to pitch investors. They showed us how they were communicating with their consumer customers -- all through LINE messenger. There were literally hundreds of threads of conversations in LINE. At some point, as the startup grows, those conversations are going to become a real pain to keep track of. Can you imagine doing all your business in LINE? (I fully realize that a lot of people do all their business in WeChat in China, etc). You can imagine that at some point, there will be new marketing automation companies that will start building marketing communication software to allow companies to communicate in a more organized manner en masse via LINE to their customers. However, this will only become a big opportunity if there are lots of startups using LINE. So, I think we are probably 3-5 years out for large B2B opportunities to emerge, because first a lot of startups need to get started.

That said, we are definitely interested in looking at these types of opportunities even as early as now, because they take time to build. :)

4) Southeast Asia is fragmented

It’s fun to just lump every SEA country together, but the reality is that SEA is quite fragmented in a way that the US is not. (i.e. language / culture / regulations / etc -- though sometimes the US seems quite fragmented - hah).

I think it’s great if startups have large ambitious of serving audiences globally, but it’s really important to tackle one market first well.

The market that everyone seems to hone in on is Indonesia. Indonesia has 250m+ people, so it’s close to the size of the US. But it’s important to further segment. If you’re trying to go after a banked population that has disposable income, then the addressable segment is probably more like 100m people. This is still a really large market, though.

But, once you start talking about population numbers closer to 100m people, then other countries start to rival Indonesia in size. Vietnam, for example, has strong tech adoption and has nearly 100m people. Thailand has nearly 70m people.

From our perspective, I think while it’s important to be cognizant of market size (for example, Singapore has ~5m people but is a great hub for building a business even if not a large addressable market on the island itself), I met a lot of people who were overthinking the SEA market landscape. As a startup, focus is super important, and nailing your product / service for 1 market of 5m people or 50m people is already really hard to do. And that 1 market -- whatever it is -- should be the focus before trying to dabble in many markets that all have completely different languages, culture, and regulations.

However, this seems counter to the advice that many entrepreneurs seem to receive in the region. If other investors are looking for you to expand to Indonesia even when you’re still tiny, then you may need to think through your strategy on fundraising. I.e. I fully realize that sometimes you have to adjust your plan to make your company more amenable to fundraising, but at the same time, VCs don’t always have the best advice either. And this is a tough balance. So maybe you start with Indonesia if you’re familiar with the market? Or maybe you start conversations with VCs well before you start your company to understand how people think about addressing one market really well before expanding.

Garden by the Bay Mid Autumn Decorations

5) Liquidity opportunities for investors are unclear

Ultimately, as an investor, I think about how eventually a company can get liquidity. And right now, even though some of the markups of high flying SEA companies are good, it’s unclear what the “typical” path of a successful large startup looks like in this region.

In the 90s, in the US, going IPO was a common liquidity path. But after consumers became wary of IPOs, M&A became the much more dominant path, though IPOs are coming back in favor again in some cases.

What this looks like for SEA is unclear and even more unclear is the timeframe. In China, the path to liquidity can be 5 years or fewer. In the US, our darling unicorns often take a decade and sometimes longer to exit. Will large US or Chinese tech companies be purchasing companies for large amounts in SEA? Is that strategic to them? Or will these companies go IPO? And depending on the country, will investors even be able to get their money out once they’ve made money? These are all questions that we have discussed and frankly don’t know the answer to, but the bet we are making is that this will be figured out in the next few years while our investments mature.

6) What are opportunities in saturated markets?

This trip got me thinking about opportunities in saturated markets. In the US, I’d argue that most categories are crowded. Crowded markets aren’t necessarily bad -- it proves demand. And if entrepreneurs can get to a certain level, any exit is good for them. But, for VCs, it’s different. This is where entrepreneur and VC incentives don’t align. A lot of VCs -- especially microVCs like us -- will generally sit out of crowded markets, because they don’t have the capital to pour into their companies to compete to become big winners. And smaller exits are not good for VCs, because they really need their winners to make up for their losers plus return more. We can debate the VC model all day, but that’s another topic for another day.

So in the US, the big opportunities as I see it are:

Products / software for unserved consumer populations along the lines of gender / race / ethnicity -- fashion tech, for example, is an area that has been long ignored

“Super high tech” that alters how we live life dramatically -- think flying cars and everything that Elon Musk dreams up

Providing software to a new generation of tech savvy people in the workplace / consumerizing B2B software for the phone -- for example, every doctor and construction worker today can use technology but 10 years ago, that was not necessarily the case

This means that entrepreneurs need to be more specialized in skillset than in a landscape like SEA. For example, if you are an entrepreneur building a new kind of autonomous vehicle, you really need to have a strong engineering background. On the other hand, if you are building a new kind of ecommerce product for an underserved customer segment, in many cases, you may not need to be technical at all, but you really need to know how to go after your customer persona to be able to out-target more general competitors who are going after a broader segment.

So what this means is that I think we will still continue to see a lot of really interesting technologies emerge from the US as well as even more products and services that will serve just about every consumer and B2B demographic. All of these are all still large opportunities, but I think the ideas that win here will just be much harder to come up with.

Just my $0.02. Would be curious for your thoughts.

Fundraising is a nebulous process that I aim to make more transparent. To learn more secrets and tips, subscribe to my newsletter.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

chapter 2

My eyes felt like screws after the seventh hour of manning the reception desk at New Ocean Hotel. My shift was almost over and every minute dragged itself over the slow blue sky. I went into the back bathroom, sat on the toilet and took a few hits from my vape pen. The high smoothed me over. I looked down at the checkered tiles of the bathroom floor and pulled out my phone. Samantha had texted me saying there was someone she wanted me to meet. This guy from her church who drank with her had just seen the lights for the first time. She described him as a sheepless shepherd who wandered around praying to a higher power. Aren’t we all sheepless shepherds I thought but then I realized maybe people had more meaningful ways of understanding their life.

She told me this guy was looking for a job and needed a place to stay. I didn’t really know how much I should care. Nothing really happened here and if some person wanted to be by the beach alone with an easy job then sure, he should come and stay for a while. If he had seen the lights at the very least it might give him some space to calm down. For me though it was boring. I’d worked here for over a year and only stayed because it gave me time to work on the free coding academy I had recently enrolled in. What I really wanted was to get out of this hotel and work for one of the startups in the bigger town to the south.

The only time the hotel got busy was during the summer. But even then, when tourist season was in full force, none of the rooms would be filled. But there was always a two-four week span when the fires forced people out from the valleys or the mountains and the rates would spike higher than they were the rest of the year. We would be filled to the brim during that time, having to deny people and everything. It was cruel to raise rates during an environmental crisis. Supposedly there was an algorithm that decided the prices for all the hotels in a thirty mile radius so the rates were always the same and there wasn’t any real competition. So it was all blameless. The mechanized blasphemous rate spiking that occurred when people’s houses were burning to the ground could be attributed to the cloud or some other unknowable piece of technology whose existence could only be hinted at and never named.

I walked back to the front desk and sat at the computer trying to decipher an error in the coding assignment I was working on. It was useless. My brain was fried and I wanted to walk out the door and go home. I couldn’t, so I booted up youtube instead. Fifteen minutes later, I was on my fourth video of this guy who had a hydraulic press. The niche of the channel was that he exclusively pressed food. Lately it seemed he’d been going to a lot of fast food restaurants. I stood there transfixed as I watched the steel metal cylinder pulverize doritos locos tacos, double doubles, fish filets and atomic chicken wings.

My manager walked in from checking on some of the rooms in the hotel and I told her to come and take a look. She sat there dazed for a while as well, occasionally offering some commentary.

“It's crazy to see food transform into such unrecognizable shapes”

“This is making me hungry”

“That actually looks kind of good”

I liked her. She wasn’t sympathetic to the owners. They directed most of their nastiness onto her and she remained nice to the employees. Sometimes though the stress from the owners overflowed onto us. But there was this mutual understanding we seemed to have of the hotel’s emotional economy. Which is to say that we were aware the owners were some real cretinous fiends who cared about nothing but the rates and money and caused people to teeter at the edge.

I think she knew I smoked in the restroom and she probably assumed I jacked off in there too, which wasn’t untrue. I indulged in what I was able to get away with. There was even this time me and this customer who I’d been chatting with locked eyes in the lobby when I came into work one morning. He and I went back into the bathroom and did all sorts of stuff. I think she knew about this too because we had security cameras but between us there was this tacit understanding that if you don’t have a big house with lots of dollars the coast in California is just a place where you go to dissolve into the sunset and burn off.

I told my manager I had a friend of a friend who needed a job and if she knew if we were hiring. She told me we weren’t but had seen that the steakhouse across the street was looking for servers. Both of us thought it was stupid that there was a steakhouse in this tiny little community. Apparently some silicon valley investor had got it in his mind that the real estate in this area would explode. The idea was that by developing some businesses and property in the area the energy of the coming boom would surge directly into his net worth. He had opened this all glass steakhouse, the type of building with exposed steel beams inside. So now, amid aging victorian homes and fields of wildflowers there was an all-glass restaurant that looked more like it made napalm than served ribeye. Maybe the meat was cloned. Either way, it had good reviews on Yelp.

I told Samantha that if her friend was really looking for work that it was available here at this pretty stupid steakhouse. We had this weird friendship that congealed around this time we did acid when we were seeing each other years ago. It was late and we were bored and awake so we decided to take a tab each and walk the couple miles down to the beachfront where we lived in central California. When we got there we took our shoes off and waded up into the ankles in the ocean. The wind was strong and the cold ocean water on our bodies began to feel like needles. There was this dingy beach motel by us with an iron gate that was rusted from the ocean breeze. It opened easily and we decided to take refuge in the stairway of the motel.

All night we stayed awake feeling the euphoria from the acid and having the full force of California beach kitsch weigh on us. I remember taking solace in eating a bag of popcorn we bought and staring at this dead fly on the windowsill. When the sun rose we walked outside and I remember Samantha made fun of me when I took a picture of the sunrise. I told her not to be an asshole, nobody is better than the sun.

On the sidewalk walking home we passed by subarus and lending libraries and stopped to look at the sky. There was a series of six orange lights high above us, moving fast and leaving a small streak of light behind them. We stood there walking with our heads fixed above. We watched them fly across the ocean and over the hills until they were far out of our sight. We didn’t even say anything to each other, we just kept walking by early morning joggers and freshly manicured lawns afterwards, staring at the sidewalk silently.

That was so long ago now and certainly before I came out and she became a Christian. We just had an unspoken understanding that we needed to head in different directions. So I moved further up the coast here and she got some tech job in the Bay Area. I remember getting these weird emails at the time from this place called Excelsior Corp about test piloting this hardware VPN product. The emails just had one line of text: “Looking for test pilots hardware VPN now” and pictures of this big black box I assumed was the hardware you would have to install to access their VPN. I always sent the emails straight to the trash but somehow they always bypassed my spam and ended up straight in my inbox.

But after some time not talking to Samantha I reached out. I was smoking my wax pen on my porch one night when I saw a bunch of shooting stars shoot over me in rapid succession. I thought of Samantha. I sent her a text asking how she was doing. She told me she’d been well but had been having these weird things happen to her. She mentioned all these emails she’d been getting and that she’d started seeing drones in the sky and lights every few months. I hadn’t seen the lights but I’d gotten the same emails. She was telling me about it and she sounded scared but also she said she was doing well.

“I’ve got a stable job and you know I go to church and stuff, and there are some really wonderful moments, just now I saw all these incredible shooting stars.”

She sounded anxious and I was worried for her. I asked her if she liked smoking dabs. She’d never tried one.

“It’s really chilled me out since that time we took acid.”

“I like my church and alcohol.”

I was happy though because despite her nervousness she seemed happy. I let her know I’d seen the same shooting stars and she was ecstatic. Since then we’ve texted and called about strange stuff we see, about weird things happening in our phones, about plans for the future, about her theories on the Greeks, about my times engaging in public sex, about the hotel, about god, and about other things. We were friends and I enjoyed hearing about her world, from the far reaches of the front desk of the New Ocean Hotel.

On the computer screen a wad of Chick-fil-A waffle fries were being squashed into potatoey dough. Me and my manager sat there watching until the steel cylinder had fully flattened the fries and the video faded to black.

My manager gestured at the steakhouse, “What do you think it's like working there? Surrounded by glass for everyone to see? I could never do that. When I worked in a restaurant the kitchen’s used to be closed off from the eyes of the customers. Now they leave it wide open, I feel like I’d go insane.”

I thought of the owners of the hotel lording over me and reprimanding me every time I looked at youtube. “I’d probably go insane too,” I said.

“I definitely would.”

When my shift was over I walked home and stopped at the convenience store to buy a pack of gummy sharks. I chewed on them while thinking about Samantha. I imagined her in church, with some ridiculous outfit on, sitting with her friend. I imagined them both listening intently to the words of the sermon, and getting up from the pews afterwards to fraternize with the other church members. I thought of how all that seemed impossible to me, making conversation to other people in a church. Maybe if I tried hard enough I could imagine it. I tried and my mind thought of being submerged in water. I thought of being in the womb. I thought of what it must be like to feel full. I thought of being in a congregation. What singing with others must feel like. I started to imagine myself there, sitting among the pews unable to join in with everyone’s song. I imagined what it would be like later on during the service, when the pastor gave his sermon. In my mind I listened to him while a stranger next to me reached for a bible on the shelf on the back of the pews and turned to the book of revelations. He placed the bible on my lap while I unbuttoned my pants and unfolded myself hard, smack dab in between the pages that talked about angels, blasphemy and a new Jerusalem. Then I imagined him stroking me while I listened to the sermon, my mind cascading through illuminated halos, until all that remained was a gold blur and me hooing softly like an owl, letting myself leak onto the thin paper pages and onto the carpet below.

It was funny to me that after that time taking acid Samantha started going to church and I got a hold on my sexuality. Too much of my life could be periodized around that trip and sometimes I felt at the brink, torn between the life I lived before and the life I was living now. But there was no actual break between the two, and they were both happening at the same time. I knew that in reality my life prior and my life after bled into each other, with experiences since then coloring the way I read the past and my life prior shaping the way I read the present. But a long black fissure stood there in my mind, dividing the two lives while they tried to congeal around the edges of the abyss. From that fissure too came not just me but Samantha, and maybe anyone else who had seen the lights. We sprouted out of it in different directions like vines, crawling out of black depths and over the grey plane of our existence, stretching into the bright orange line of the horizon.

My teeth smushed the blue-white body of the gummy shark in two. I chewed one piece and stared briefly at the shimmering half body of gelatin I held in between my two fingers. It would be possible for Samantha’s friend to find a job here. I even had an extra room in the converted apartment of the old Victorian house I rented. Then what? I suppose nothing, I would continue with my life, trying to learn to code and working at the hotel. Who knows what would happen when we met. There was this sensation I had though, that everyone who me and Samantha came in close contact with was somehow also sprouting out of the abyss, extending themselves over that grey plane and trying to reach the sun.

0 notes

Text

OK, I'LL TELL YOU YOU ABOUT FEATURE

They seemed to have lost their virginity at an average of about 14 and by college had tried more drugs than I'd even heard of. From their point of view, as big company executives, they were less able to start a company, it doesn't seem as if Larry and Sergey seem to have felt the same before they started Google, and so far there are few outside the US, because they don't have layers of bureaucracy to slow them down. It meant that a the only way to get rich.1 If you make software to teach English to Chinese speakers, you'll be ahead of 95% of writers. We arrive at adulthood with heads full of lies.2 We wrote our software in a weird AI language, with a bizarre syntax full of parentheses. That's an extreme example, of course, that you needed $20,000 in capital to incorporate.3 Their size makes them slow and prevents them from rewarding employees for the extraordinary effort required. Doing what you love in your spare time.4 Young professionals were paying their dues, working their way up the hierarchy. By giving him something he wants in return.

Once they saw that new BMW 325i, they wanted one too.5 If you simply manage to write in spoken language. Languages less powerful than Blub are obviously less powerful, because they're missing some feature he's used to. The kind of people you find in Cambridge are not there by accident.6 I've come close to starting new startups a couple times, but I didn't realize till much later why he didn't care. We'd interview people from MIT or Harvard or Stanford must be smart. Indians in the current Silicon Valley are all too aware of the shortcomings of the INS, but there's little they can do about it. When you're too weak to lift something, you can always make money from such investments.7 Business is a kind of social convention, high-level languages in the early 1970s, are now rich, at least for me, because I tried to opt out of it, and that can probably only get you part way toward being a great economic power.8 It must have seemed a safe move at the time. At the end of the summer.9

It's not merely that you need a scalable idea to grow.10 How much stock should you give him? Users love a site that's constantly improving. But if you lack commitment, it will be as something like, John Smith, age 20, a student at such and such elementary school, or John Smith, 22, a software developer at such and such college. There are two things different here from the usual confidence-building exercise.11 But it means if you made a serious effort. Bill Gates out of the third world.12 What's going on? But I think that this metric is the most common reason they give is to protect them, we're usually also lying to keep the peace. The kind of people you find in Cambridge are not there by accident.13

Frankly, it surprises me how small a role patents play in the software business, startups beat established companies by transcending them. The problem is that the cycle is slow. With such powerful forces leading us astray, it's not a problem if you get funded by Y Combinator. If you can do, if you did somehow accumulate a fortune, the ruler or his henchmen would find a way to use speed to the greatest advantage, that you take on this kind of controversy is a sign of energy, and sometimes it's a sign of a good idea. Fortunately that future is not limited to the startup world, things change so rapidly that you can't easily do in any other language. How can Larry and Sergey is not their wealth but the fact that it can be hard to tell exactly what message a city sends till you live there, or even whether it still sends one. They build Writely.14 I'm not sure that will happen, but it's the truth. Stanford students are more entrepreneurial than Yale students, but not because of some difference in their characters; the Yale students just have fewer examples.

And whatever you think of a startup. In the US things are more haphazard. I see a couple things on the list because he was one of the symptoms of bad judgement is believing you have good judgement. There are a couple catches. Instead of being positive, I'm going to use TCP/IP just because everyone else does.15 Being profitable, for example, or at the more bogus end of the race slowing down. An example of a job someone had to do.16 But actually being good. There are a lot of people were there during conventional office hours.17

I'll tell you about one of the most surprising things we've learned is how little it matters where people went to college.18 In Lisp, these programs are called macros. That's where the upper-middle class convention that you're supposed to work on it. And since most of what big companies do their best thinking when they wake up on Sunday morning and go downstairs in their bathrobe to make a conscious effort to keep your ideas about what you should do is start one.19 The most powerful wind is users. We're just finally able to measure it. And not only did everyone get the same yield. VCs need to invest in startups, at least by legal standards. Ten years ago, writing applications meant writing applications in C. If you have to operate on ridiculously incomplete information.

Notes

Foster, Richard Florida told me about several valuable sources. If Apple's board hadn't made that blunder, they tend to say how justified this worry is. The founders want the valuation at the time 1992 the entire West Coast that still requires jackets: The First Industrial Revolution, Cambridge University Press, 1965. Yes, there would be enough to be a win to include things in shows is basically zero.

Different kinds of startups that has become part of your mind what's the right mindset you will fail.

But although I started using it out of loyalty to the founders' salaries to the traditional peasant's diet: they had first claim on the one hand they take away with the earlier stage startups, just monopolies they create rather than admitting he preferred to call them whitelists because it reads as a kid, this is the notoriously corrupt relationship between the government. As the name Homer, to mean starting a business, A. The Department of English Studies. Yes, strictly speaking, you're pretty well protected against such tricks initially.

There are also the 11% most susceptible to charisma. Every language probably has a word meaning how one feels when that partner re-tells it to profitability on a road there are no longer needed, big companies to say that YC's most successful startups of all the page-generating templates are still expensive to start over from scratch, rather than ones they capture.

There are two simplifying assumptions: that the Internet, and judge them based on revenues of 1. If the company goes public. This is one resource patent trolls need: lawyers. When that happens.

The only launches I remember are famous flops like the bizarre consequences of this type of proficiency test any apprentice might have 20 affinities by this, though more polite, was starting an outdoor portal. The Duty of Genius, Penguin, 1991, p. The danger is that in practice signalling hasn't been much of observed behavior. When I say in principle is that intelligence doesn't matter in startups tend to be when I was genuinely worried that Airbnb, for example, the startup after you buy it despite having no evidence it's for sale.

Another thing I learned from this experiment: set aside an option pool. So if they don't want to start a startup in question usually is doing badly in your country controlled by the government. But in a company grew at 1% a week for 4 years.

We added two more investors. The reason this subject is so hard to imagine how an investor, and that often doesn't know its own momentum. We think. I'm talking here about everyday tagging.

They thought most programming would be possible to bring corporate bonds to market faster; the point of a large organization that often creates a rationalization for doing so much to generalize.

Many people feel good. So instead of being interrupted deters hackers from starting hard projects. The idea is that it was overvalued till you see them, initially, were ways to make your fortune? In fact the decade preceding the war.

One father told me about a form that would appeal to investors.

Some graffiti is quite impressive anything becomes art if you tell them to justify choices inaction in particular took bribery to the traditional peasant's diet: they hoped they were only partly joking. If a big angel like Ron Conway had angel funds starting in the first phase. You're going to create one of those you can eliminate, do not try too hard at fixing bugs—which, if they stopped causing so much from day to day indeed, is due to the table.

The hardest kind of gestures you use the wrong ISP. But they've been trained to expect the second component is empty—an idea is stone soup: you post a sign saying this cupboard must be kept empty. The two guys were Dan Bricklin and Bob Frankston. I have set up grant programs to run an online service, and they were, they'd be called unfair.

My work represents an exploration of gender and sexuality in an era of such high taxes?

So the most visible index of that, in one of the markets they serve, because she liked the iPhone SDK. For example, because a it's too hard to pick the former, because it is.

If you ask that you're small and traditional proprietors on the side of the junk bond business by Michael Milken; a new airport.

The biggest exits are the only audience for your side project. You're not one of their portfolio companies. He did eventually graduate at about 26.

A lot of time on schleps, but he doesn't remember which.

When I talk about startups. It's also one of the statistics they use the wrong algorithm for generating their frontpage. The reason Y Combinator only got 38 cents on the other: the source of food.

#automatically generated text#Markov chains#Paul Graham#Python#Patrick Mooney#college#sign#things#Duty#henchmen#A#language#cents#peasant#resource#company#startup#diet#Bill#characters#idea#behavior#lot#problem#type#role#First#whitelists#Languages#li

1 note

·

View note

Text

Juul and the business of addiction

New Post has been published on https://tattlepress.com/business/juul-and-the-business-of-addiction/

Juul and the business of addiction

Several years ago, I went to a splashy launch party for a new tech product, which is a pretty normal thing for tech companies to have. It was at a hip warehouse space in Manhattan, there was cool lighting and a great DJ, free food — the company had pulled out all the stops. And the company had invited a ton of Instagram influencers and model types, so there were lots of beautiful young people there doing exactly what the company had hoped they’d do: taking photos and videos with the new product, talking about how cool it was, and posting it to social media.

Now, if I was talking about a new smartphone, or a camera, or a laptop, this party would not have stuck out in my mind, but this party was for a product called the Juul. And the Juul was — and still is — one of the most potent and effective nicotine delivery devices that’s ever been created. Juul’s big innovation was a nicotine formulation that made its vape hit just like a cigarette. And the party kicked off a marketing blitz that seemed pretty directly targeted toward teenagers on social media.

After that, the Juul became a sensation — and a sensationally dramatic story. The marketing helped, but also it turns out nicotine is addictive as hell. A Stanford tech startup that had been founded to disrupt the smoking industry had upended years of US tobacco regulation, gotten a new generation of teenagers addicted to nicotine after years of declining smoking rates, and eventually found itself valued at $38 billion after a huge $12.8 billion investment from Altria — the company that used to be called Philip Morris. You probably know it by its most famous product: Marlboro cigarettes.

Then it all fell apart: the lawsuits came, the FTC sued to unwind the deal, the valuations of both Juul and Altria collapsed, and Juul itself faces being regulated entirely out of the market in the United States.

How did this all happen? How did a startup that was founded to stop smoking end up in the pocket of Marlboro? How did Altria screw up this investment so badly? And how did a couple of Stanford kids figure out a better cigarette before the cigarette industry?

To find out, I invited Lauren Etter on the show. Lauren is an investigative reporter at Bloomberg News and the author of a new book called The Devil’s Playbook: Big Tobacco, Juul, and the Addiction of a New Generation. Lauren tells us the story of how the cigarette industry went from hiding and lying about research that showed nicotine was addictive to being one of the most regulated industries in the country — and then, how that provided an opening for Juul to do things the cigarette companies could never get away with.

The book is terrific — even if you don’t care about nicotine and smoking, if you’re a Decoder listener, you’re going to recognize a lot of themes in this conversation. There’s a big industry that’s slow to adapt, there’s a startup that’s moving fast and breaking things, there are regulators around the world who don’t quite know what to do, and at the center of it all, there’s a big question about our society’s relationship with a product that might be bad for people — and that people still want.

Just a couple days after we recorded this episode news broke that Juul has agreed to settle a lawsuit brought by the state of North Carolina that claimed the company’s marketing practices caused a sharp rise in vaping among minors. Juul will pay a $40 million settlement, but it’s also agreed to something else: it won’t use anyone under the age of 35 in its marketing anymore. The party is officially over.

The following transcript has been edited for clarity.

This is your first book, and I have to say it was a very impressive first book. We covered the Juul story at The Verge as a tech story, but you’ve written a health story, a really complicated business and regulatory story, and also the story of the tobacco industry and what it has become in this country. How did you start looking at Juul in this way, and how did you end up writing a book about it?

I started writing about Juul after the outbreak of lung injuries, this mysterious outbreak called EVALI [e-cigarette or vaping use-associated lung injury]. I started writing about it from a health perspective and trying to figure out what was going on, just like the rest of the nation trying to figure [this] out. Is this related to vaping? So I started covering some of those stories, and then I became interested in Juul as a business story. It was fascinating to me that a company that had found itself in the middle of this public health crisis was a Silicon Valley firm.

As I embarked on a book, I was really endeavoring to tell the story of Juul, but I quickly realized it was impossible to tell the complete story of Juul without telling the story of the tobacco industry. Those two industries were so intimately intertwined that it became evident to me that I needed to also write about the tobacco industry. That’s why I ended up with these two intertwined narratives.

Give people the really short version of the Juul story. This is a famous product. It was all over the news. Lots of people use a Juul, but it has a really sharp rise, and then a really sharp fall.

Most people know about Juul having launched in the summer of 2015 with this flashy nicotine device called Juul, and quickly taking off and taking over the entire industry and leading to a youth health crisis. All the teenagers started using it. But actually, the founders of Juul had been working on coming up with a better, healthier, less harmful alternative to the cigarette for years before Juul. Adam Bowen and James Monsees, two Stanford grad students, started working on… it’s almost like a myth and a legend by now. A lot of people know this story. They met at Stanford, in the design school. They were smoking cigarettes out back as they kind of pondered their next project, and they realized that it was idiotic to be smoking this burning stick, essentially shredded tobacco leaf rolled in paper, lit on fire. The same product that people had been using for more than a century.

And here they are in the heart of Silicon Valley, where everything is ripe for innovation. And they realized, why hasn’t the cigarette been innovated on? So they set out to innovate the cigarette. As they embarked on that, they found some of these old tobacco documents that had surfaced during the 1990s in the heat of the tobacco wars, and there were millions of documents that the tobacco companies had to hand over, to make public, as a result of litigation that had nearly buried them. They tapped into that, and had many, many iterations of their product before it became Juul. It launched in 2015, ultimately, and just became the most popular e-cigarette on the market. They marketed it on social media, on Instagram, on Facebook, on Twitter. They sent kind of traveling troupes of these nicotine Juul marketers that handed out free samples at parties, on yachts, in the Hamptons, at raves, and it just became extremely popular.

It became popular among 20-year-olds, and among teenagers as well, middle school and high school students. So that was the moment, as it became just a runaway success, that it attracted the attention of public health regulators, of the FDA, of members of Congress. It just became this huge issue, where Scott Gottlieb, the then-FDA commissioner, called it an epidemic of youth usage. So basically, the company found itself under this incredible scrutiny from every angle. And at the same time, the traditional tobacco industry had also been trying to innovate on cigarettes, their declining business. The cigarette had been in decline for decades. Everybody agreed that the business was only going to continue to decline as people realized the adverse health effects of smoking, and it was not as cool to smoke cigarettes anymore.

And so as big tobacco tries to innovate, they cannot out-innovate Silicon Valley. So at the end of the day, Altria, the maker of Marlboro cigarettes, decides to invest in Juul. In my book, I write that was the moment the glass shattered for Juul. It just attracted so much scrutiny, because all of these years, the founders of Juul had been saying, “We are the anti-cigarette. We’re going to kill the cigarette. We’re going to kill the tobacco industry,” and suddenly they’re in bed with the tobacco industry. That really kind of put them on blast in a new way.

They were under health regulators’ scrutiny, and their valuation, which once stood at $38 billion, was just tumbling quarter after quarter after quarter. And now, there’s been a huge reorganization in the company. They brought in all these new executives, many from the tobacco industry, and they’re essentially fighting for their survival right now. Juul, like every other e-cigarette maker, has submitted an application to the FDA, and now the FDA has to determine whether or not it’s in the public health’s interest to allow this product to continue to be marketed.

Basically, we’re all waiting. It’s expected sometime this year, for the FDA to decide whether or not it can be sold. If the FDA does not allow it to go forward, Juul has no product to sell. And if it does, I think Juul is well-positioned to continue to grow and take over the market. So they’re at a real inflection point right now.

That is just a staggering rise and fall. It’s two kids at Stanford looking at a product that they’re using, doing the tech industry thing, asking this kind of hilarious bubble question of, “Why hasn’t anybody innovated this thing,” realizing that actually lots of people have tried to innovate it, using some of that, and then all the way to now potentially facing regulatory doom.

Exactly.

The big innovation with Juul was not really the design or the pods. It was the nicotine formulation. How did they stumble on a nicotine formulation that hits like a cigarette? Because early vapes were really, really harsh.

This is Juul’s secret sauce, the nicotine salts, of course. Early [e-cigarettes], what they did was they essentially just took nicotine and they added some flavors to it. But the problem with just using nicotine is, it’s extremely harsh. It has a high pH level. It burns your throat. Early iterations of e-cigarettes, they could only put in small amounts of nicotine so it wouldn’t be so aversive to your lungs. The problem with that was that it didn’t satisfy smokers. because there wasn’t enough nicotine in it. So they’d have to puff and puff and puff on the thing and it just wouldn’t deliver the satisfaction. So, that had been the number one complaint by e-cigarette users.

So, Adam and James, they had done tons of research. They had delved into these tobacco archives, which contained all kinds of science about nicotine and about tobacco. The science of tobacco smoke and nicotine chemistry is extremely complicated and complex, and they were able to use some early research that showed if you modify the pH levels of tobacco smoke you can deliver different satisfaction levels, enjoyment levels, that type of thing. There’s also a body of research that showed, if you add organic acids to nicotine, it lowers the pH but you can have higher levels of nicotine. Essentially, by adding the organic acids, you create a nicotine salt, and that allows the pH to go lower, but you have a higher amount of nicotine. So what that does is enable you to inhale a large amount of nicotine without burning your throat, without you starting to cough a lot.

I should also point out that they hired tobacco industry scientists. They had them on speed dial. They would call them and they would ask about the different various organic acids and how that could modulate the pH. And they did all kinds of research and they absolutely turned to tobacco industry executives and to the tobacco files, the archives, to help them solve the problem. They eventually did their own experimentation in Dogpatch in their offices there, where they were adding various organic acids to nicotine to see what the most satisfying ones were. And they ended up going to New Zealand where they did their own tests on human subjects, including on Adam Bowen himself, to determine which organic acid in nicotine would give you the highest level of satisfaction, and what would make your heart race the fastest. When you take these little surveys, what would be the most satisfying one?

So they did all kinds of just really organic research and ended up settling on benzoic acid as the organic acid that was the most satisfying. This enabled them to do something that no other company had really done, which is devise a nicotine solution that had a high nicotine content, in this case 5 percent, which was ultimately marketed, but with a very low aversive component to it.

They picked benzoic acid. They have a patent. The patent lists every other kind of acid you might want to use down to citric acid. That prevents anyone else from doing this, right? Was that it? Was there another way around this problem? Because when I first saw that patent, I was like, “Oh, Juul’s going to win. Now they can block everybody else from doing the thing that made their product better than everybody else.”

There’s definitely been IP litigation over this. And there probably will be in the future. I just don’t know how much Juul is going to be able to prevail on essentially owning chemistry. This is basic organic chemistry. I don’t know if it, at first glance, gives them the patent protection or the IP protection, that you might think.

I’m really interested in that arc and sort of pulling apart the bits and pieces of that, but what struck me about your book is that you don’t start with Juul at all. You start with Altria, which is the company that was known as Philip Morris, that made Marlboro, and you start with them in sort of the very late ’90s, early 2000s. And it seems like what the entire cigarette industry was struggling with was, we’re going to be a regulated industry.

We’ll be intertwined with government regulators. We’ll be intertwined with health officials. We have to learn to be that kind of company where the government is kind of always up in our shit. Tell me about that, because there’s a really big parallel, not in terms of the product, but in terms of the attitudinal shift that the entire tech industry is facing right now.

You and I are talking, and Congress is literally talking, about antitrust bills, simultaneously with our discussion today. But it just feels like that attitude shift created the opportunity for someone to not have the baggage and make the Juul, when if Philip Morris had invented the Juul, I mean, their business would have been secured in a different way, but they were just unable to.

Yes, that’s exactly right. I started the book in the middle of a hurricane in Puerto Rico, because I felt like it was emblematic of what the industry was going through, the tobacco industry.

The book starts in the middle of a hurricane. You were not in the middle of a hurricane.

Right, correct. The book starts in the middle of a hurricane in Puerto Rico, and Philip Morris, the company now known as Altria, had gathered all of its corporate relations officials and executives, and met there as kind of a retreat to talk about this huge moment in the industry where they had to admit that they had deceived the American people, that they had lied, that they had covered up all of this information and evidence about how deadly cigarette smoking was, and it had all come out into the public.

The FDA commissioner, David Kessler, at the time, had made it his mission to go after the tobacco industry to bring it under its regulatory authority for the first time. State attorneys general were suing the tobacco industry and the tobacco companies for all of the public health effects and the costs related to treating smoking-related disease, and every week there was a new headline on the front page of the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times about the misdeeds of the tobacco industry in the ’90s.

It really was this important moment that I thought almost paralleled where we are today with Juul. So, they realized that they needed to have this permission to exist, and Juul essentially finds itself in the exact same position now, where they’re kind of operating only if the FDA gives them permission to operate. They’ve realized that they created a youth usage crisis, or helped create it, and that they have to be incredibly careful about it. But the interesting thing is that when Juul launched, when Adam and James decided to innovate on the cigarette, they had none of that baggage that the tobacco industry had. They had not been through the trenches, and they didn’t approach the industry — this highly addictive product, nicotine — they didn’t approach it with the necessary care in order to give their product a chance at surviving and asking permission from society.

It’s like the motto of Silicon Valley, “Move fast and break things. Ask for forgiveness, not permission.” And that’s exactly the mentality that they embodied early on when they launched Juul, and it’s also the mentality that allowed them to crush the market, to take over, and to basically flood the nation with Juul. So there are lots of similarities, lots of parallels between those two narratives.

Well, let me ask you about that, because the lack of baggage enabled them to make a product that Philip Morris and the other big tobacco companies had been trying to invent for years, and because of their own regulatory problems and their own wacky international corporate structures, they weren’t really able to do it well. And the Juul team had none of that baggage. They were able to say, “What people want is nicotine,” which the tobacco companies really could not say, given the regulatory scrutiny. And then they were able to deliver the nicotine salt formula in the pods of the Juul.

I think a lot of people will tell you they’re very happy using a Juul instead of smoking a cigarette, and that is probably a net good, although I have some questions about that too. The thing that I struggle with in this entire story is, “Well, it’s better than smoking.” And so if the tobacco companies were not able to make this product, is it a net good thing that a startup that made a lot of mistakes along the way didn’t need to ask permission to exist, eventually did develop a product that is, in some measurable way, better than smoking?

You’re hitting on the exact controversy, and I think it’s super important to talk about it in this way. First of all, it’s partly a socio-cultural question about nicotine. Why do people use nicotine? Why do they want to use nicotine? It provides pleasure. I mean, it does lots of great things. It provides pleasure. It can help you concentrate. It can help you focus. It can relax you. There are all kinds of appealing aspects to nicotine, I should point out, and this is also a very important point, it’s not the nicotine in cigarettes that kills people. Nicotine has some adverse health effects, but largely not many. There are even some studies showing that nicotine can help in the treatment of serious diseases, including Parkinson’s.

But what kills people when they smoke cigarettes, the deadly aspect of a cigarette, is the combustion. And this is kind of the thing that Adam and James focus on, is the combustion. It’s the lighting on fire, the burning, inhaling these toxic chemicals that form tar droplets that end up affecting the lining of your lungs and causing lung disease. So people smoke cigarettes because they want nicotine. Why do people want nicotine? Well, they’re addicted to it. I think the addiction element is sort of the most important and most interesting aspect to focus on, because what’s so bad about nicotine? Well, you could potentially become a lifelong user of nicotine. So I think when we’re talking about adult smokers, we know the reason they smoke is because of the nicotine. They want the nicotine fix.