#anishinaabeg artists

Photo

Ogimaa Mikana. Don’t be shy to speak Anishinaabemowin when it’s time. Bayfield St., Barrie, Ontario; Biskaabiiyang. North Bay, Ontario; Untitled (All Walls Crumble). Ottawa, Ontario; Anishinaabe manoomin inaakonigewin gosha. Peterborough, Ontario.

Ogimaa Mikana is an artist collective founded by Susan Blight (Anishinaabe, Couchiching) and Hayden King (Anishinaabe, Gchi’mnissing) in January 2013. Through public art, site-specific intervention, and social practice, we assert Anishinaabe self-determination on the land and in the public sphere.

The Ogimaa Mikana Project is an effort to restore Anishinaabemowin place-names to the streets, avenues, roads, paths, and trails of Gichi Kiiwenging (Toronto) - transforming a landscape that often obscures or makes invisible the presence of Indigenous peoples. Starting with a small section of Queen St., re-naming it Ogimaa Mikana (Leader's Trail) in tribute to all the strong women leaders of the Idle No More movement, the project hopes to expand throughout downtown and beyond.

“The Anishinaabeg endure. We do so through settler colonial time, and across space. We do so in contention. Untitled (All Walls Crumble) considers this movement. To be Indigenous in the city is so often a struggle for recognition, to be seen, and to resist the erasure that is common in Toronto, Montreal, Ottawa, etc. Yet with recognition also comes appropriation and co-optation. In this unease, we consider the benefits of erasure, or at least, covert movement.

Inspired by stories of our relatives and ancestors counting coup, and Basil Johnson’s description of warfare more generally, the Ogimaa Mikana Project considers the tension between visibility and invisibility to challenge settler colonial logic. Against a crumbling wall holding up Ottawa’s major highway - scheduled for demolition and replacement - we draw attention to the ways the settler state recycles itself, and by extension, affirms its legitimacy. We see it and resist in provocative ways that mirror a there/not there presence.

Against this crumbling wall, we reclaim space for an anti-recognition: to speak to each other, as Anishinaabeg, as communities pushed out by gentrification, as the colonized, and offer a refrain and a sign of defiance: “Wakayakoniganag da pangishin. Nin d'akiminan kagige oga ahindanize.”

#Ogimaa Mikana#susan blight#Hayden King#anishinaabeg#anishinaabe#Anishinaabe artist#anishinaabeg artists#Anishinaabe Art#indigenous art#INDIGENOUS CONTEMPORARY ART#contemporary art#public art#place-naming#intervention#art intervention#contemporary anishinaabe art#indigenous collective#indigenous artist collective#Anishinaabemowin

855 notes

·

View notes

Text

More art of Nanabozho bc he is so silly and scrimblo!~

A doobius little creature getting up to mischief

#art#digital art#nanaboozhoo#nanabush#nanabozho#wenabozho#anishinaabe#anishinaabeg#anishinaabe art#anishinaabe artist#ojibwe art#ojibwe#ojibway#ojibwa#first nations#native american#native#indigenous#indigenous art#indigenous artist#furry#furrydrawing#furry community#furry art#rabbit

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Self-Portrait in Reclaimed Copper

Katheryn Wabegijig, b. 1979

Anishinaabe (Ojibwa/Odawa)

Ketegaunseebee/Garden River First Nation

Hammered pennies on stained wood, 2016

Katheryn Wabegijig of Ketegaunseebee/Garden River First Nation portrays herself as though framed in a Canadian penny. At its centre, the artist used a hammer and nail set to pound out the Queen's face and text on the copper pennies that form her silhouette. This laborious act was both an affirmation of copper as a highly significant material to the Anishinaabeg before European contact, and the artist's assertion of her strength as an Indigenous person freeing herself of the repressive effects of colonization.

#katheryn wabegijig#pennies#copper#ojibwa#indigenous peoples#first nations#canada#royal ontario museum#the rom#art

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

WINDOW 57: VIVIENNE BESSETTE (JANUARY 28 - MARCH 17, 2023)

WINNIPEG’S ONLY 24 HOUR ARTIST-RUN CENTRE PRESENTS VIVIENNE BESSETTE

Location: Artspace Building, corner of Bannatyne @ Arthur [sidewalk level]

window is pleased to present our fifty-seventh installation:

~~

Image descriptions:

[Image 1]: An oversize poster hangs in the window. It is green throughout with details in red, yellow, purple, and blue. It reads "COMPOST HOTLINE. Dial Now!" Strips dangle at the bottom with a phone number on some of them, as if ready to tear off. The imagery includes a red phone, compost, and superimposed images of flowers and organic material.

[Image 2]: A regular size version of Bessette's poster is stapled up on an outdoor bulletin, among other posters.

~~

Party line, 2023

Material list: RJ-45 talking to RJ-11, exponential growth of compost slime, spiritual technology of the tear-off flyer, landlordism, call waiting as extra sensory perception, antidote.

By Vivienne Bessette. On view until March 17, 2023.

~~

Artist statement:

The compost hotline is just a phone number but it is also a network of gardens, an imaginary friend and an always-developing informal online collab space where artists, gardeners and community organizers can temporarily freeze the flow of the internet (spirit net) to reflect and share research, personal archives, or the 2am–4am late-night google unconscious. It is meant as an alternative to death for precious trans liminal space, digital scraps, not-to-be-forgotten embodiments, or otherwise entombed hard drive materials. To apply, upload files into the google drive as a constellation of web links, screen shots, images, a recording, or text about what is keeping you up at night.

~~

About the artist:

Vivienne Bessette (b. 1982) is a queer settler & interdisciplinary artist whose ancestry ties them to Ireland, Croatia, France, and the Metis settlements of Cayer, MB, and Red River. Bessette incorporates drawing, painting, woodworking, sculpting, dying, writing, fermenting and building relationships with plants into their practice. They work in and out of the studio, the garden and the kitchen, developing sustainable and alternative modes of food production and utilizing unconventional materials. The strength of entangled and interdependent community is at the stomach of Bessette’s process. Bessette holds a BFA from Simon Fraser University. They have been involved with multiple garden and food-based collectives, including Commons Garden at Sahalli Park Community Garden, Garden Don’t Care, Looking at the Garden Fence, and the project What artists bring to the table for the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria with Derya Akay and Kurtis Wilson. Bessette was a Food Coordinator for Slow Waves Small Projects on Mayne Island. They have been published in The Capilano Review (“Pattern of Pears,” 2020 and “Organize Your Building with the Support of the Vancouver Tenants Union with the Belvedere Residents,” 2018). They live and work on the stolen and unceded territories of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm, Sḵwx̱wú7mesh and səlí̓lwətaʔɬ Nations.

window is located on Treaty 1 Territory, the original lands of Anishinaabeg, Cree, Oji-Cree, Dakota, and Dene peoples and the Homeland of the Métis Nation. window is co-curated by Noor Bhangu, Mariana Muñoz Gomez, and Jennifer Smith.

This installation was made possible with the generous support of the Winnipeg Arts Council.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

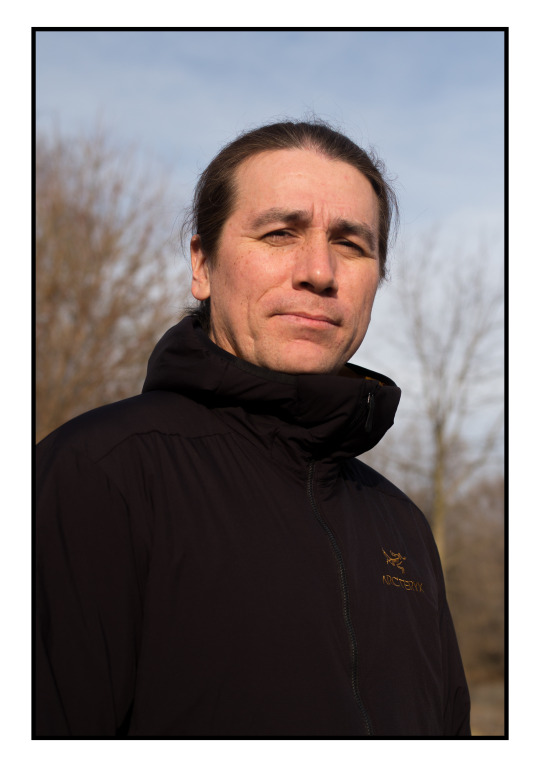

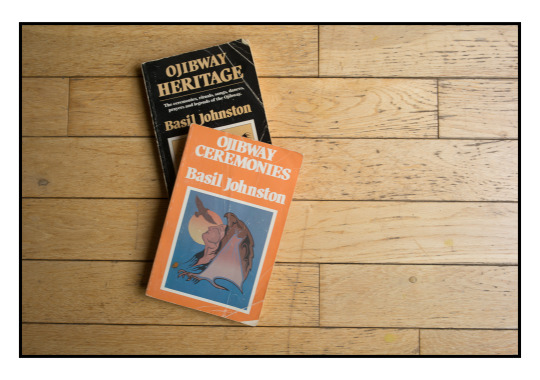

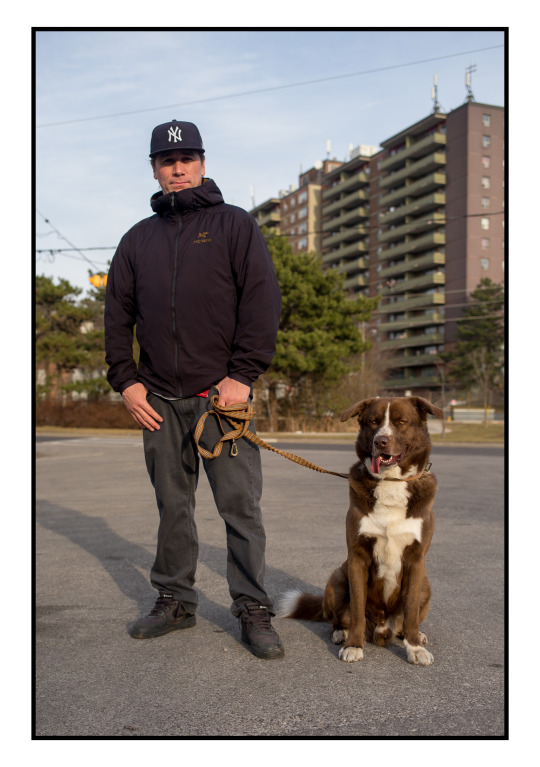

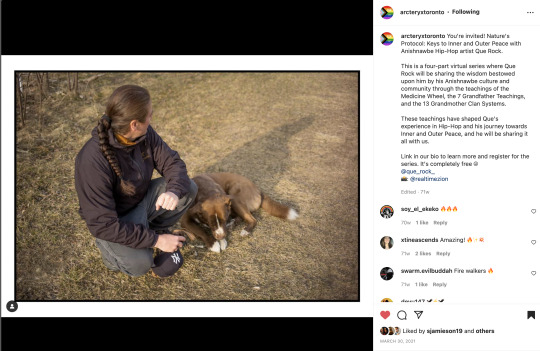

I introduced B-boy/Rapper/Graffiti artist Que Rock to the team to share his Anishinaabeg knowledge. I followed up with some photo to be used as a post on the Arc’ Toronto account.

1 note

·

View note

Text

I’m actually not interested in justice.

I’m interested in Indigenous resurgence [...], addressing gender violence, movement building, linking up and creating constellations of co-resistance with other movements. [...]

[T]he state has co-opted narratives of justice in complex ways, especially against Indigenous and Black peoples. [...] The criminal justice system is another narrative of justice that ends up not being about justice at all; it ends up murdering [...] and criminalizing our communities. [...] [I]n Canada [...] we have a government that is very good at neoliberalism and seducing our hope [...].

-------

So I don’t think about justice very much. I think about resurgence and movement building. [...] I think [...] when we are talking about justice or solidarity [...], we need to start within our intelligence systems [...] the systems of ethics that are continuously generated by a relationship with a particular place, with land [...]. It is an embedded and interwoven spiritual, emotional, and social system of intelligence that fosters independence, community, and self-determination in individuals. It is centered around individuals, a diversity of individuals acting in a way that promotes and brings about more life [...]. The well-being of individuals is directly linked to the well-being of collectives. [...] These processes allow the community of people impacted by the imbalance to learn the context of the individuals directly involved. [...] It focuses on repairing and regenerating relationships [...]. It is a supportive system of processing trauma [...], of accounting for losses or hurt. [...] [S]eeking recognition with the settler-colonial state is a process of co-option and neutralization [...] that guts our resistance movements [...].

When I consider this within Anishinaabeg thought, my understanding is that we are more a collection of collectives, so I don’t see a tension between individuals or collectives. Individuals are hubs of networks. When an individual is hurt, then the system is out of balance. [...] I don’t want to be too prescriptive here because for Indigenous peoples this kind of knowledge has to be learned in a particular way. You can’t read an academic paper or a book about it and think you know what you are talking about. [...] This kind of knowledge needs to be learned in relationship to the place that generated it [...]. There are different ways of interpreting knowledge that collectives of people need to figure out. [...] The point of resurgence isn’t to present case studies and then have them replicated in other communities. That won’t work. [...]

-------

I’ve been thinking a lot about constellations within Nishnaabeg thought. Dene/Cree scholar Jarrett Martineau’s dissertation, “Creative Combat: Indigenous Art, Resurgence, and Decolonization,” uses the artistic practices of a diverse series of Indigenous provocateurs to examine the decolonizing potential of art-making [...]. He really advances this idea of the constellation, drawing upon the work of Indigenous artists’ collectives and folks like Black Constellation. [...]

We can’t rely on the culture that capitalism creates. We just can’t. We can’t achieve Indigenous nationhoods while replicating antiblackness. We can’t have resurgence without centering gender and queerness [...]. Therefore, we need to create constellations of connections with other radical thinkers and doers and makers. [...] That’s why resurgence is so important. I am not particularly interested in holding states accountable because the structure, history, and nature of states is exploitative by nature.

I’m interested in alternatives, I’m interested in building new worlds.

-----------------

Leanne Betasamosake Simpson. “Indigenous Resurgence and Co-resistance.” Critical Ethnic Studies. Fall 2016.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Going to copy one of my favorite Twitter artists (Liz Anna Kozik/@chase_prairie) and run a climate donation drive today in the wake of the IPCC report release.

(but on Tumblr instead bc I only really have followers here)

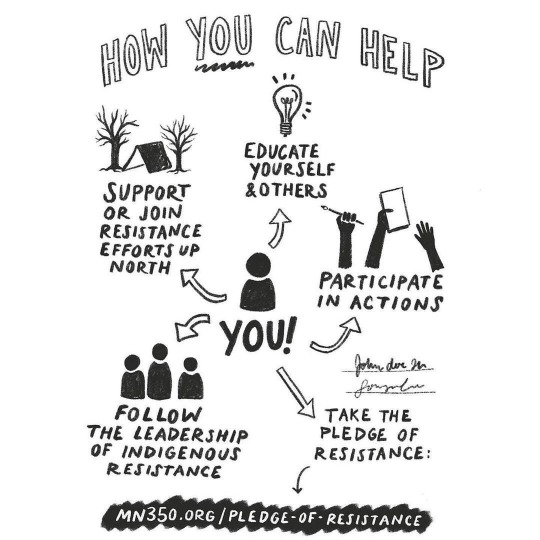

I'll offer custom drawings of the plant, animal, or bladed weapon of your choice in exchange for new donations of at least $20 to stopline3.org. Send a screenshot of your donation receipt, your subject, and your mailing address to me on here or to [email protected] and I'll mail you the drawing (4x6, ink+watercolor).

Support climate justice and fight climate despair!

#climate justice#climate action#un ipcc report#climate crisis#stop line 3#stop line three#line 3#art#ipcc

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

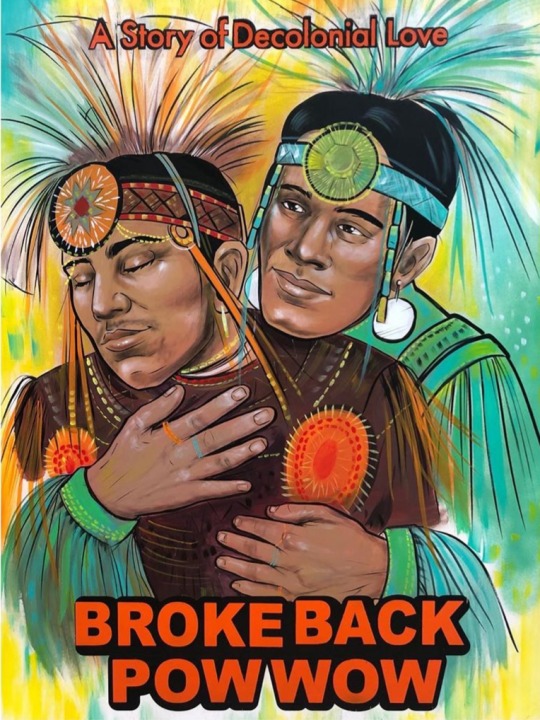

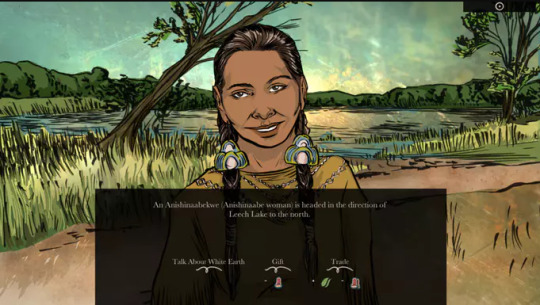

When Rivers Were Trails: an indigenous take on Oregon Trail

When Rivers Were Trails is a "Native-themed decision-based RPG" based on the classic Apple ][+ game "Oregon Trail," in which you play an 1890 Anishinaabeg person who has been forced off your land in Fond du Lac, Minnesota and must migrate through the northwest to California.

The game was created by Elizabeth LaPensée -- an Anishinaabe game creator from Baawaating -- and a team of more than 20 indigenous writers and artists, including visual artist Weshoyot Alvitre and composers Supaman and Michael Charette.

LaPensée says that she used to joke that she wanted an Oregon Trail-style tee with the slogan "You have died of colonization," and that was the germ of the idea that she pitched to Dr. Nichlas Emmons for the Indian Land Tenure Foundation's project to develop K-12 Lessons of Our Land curriculum.

The writers used drew on their own families' stories of displacement to craft the narrative and interactions in the game.

https://boingboing.net/2019/04/17/you-have-died-of-colonization.html

11K notes

·

View notes

Text

Canadian Holiday Inbound: Canada Day, July 1, 2021

Fellow Mozillians,

[Content warning: This involves the historic realities of, and recent news about, the Indian Residential School System in Canada. Please call the National Indian Residential School Crisis Line at 1-866-925-4419 (Canada/US only) if you or someone you know is triggered while reading the content.]

They are called "Truth And Reconciliation" commissions because there can be no reconciliation if we are unwilling to confront the truth.

In the past three weeks, undocumented mass burial sites were revealed at two Canadian Residential Schools, the bodies mostly those of children. More than 130 such schools were funded by the Canadian government during the residential schools system's existence.

From 1831 to 1996, anchored in legislation with names like the Gradual Civilization Act of 1857 and the Gradual Enfranchisement Act of 1869, thousands of Indigeneous children in Canada were forcibly taken from their parents and sent to Residential Schools run by churches and the government.

Through the Residential School System, the Canadian government ran a program explicitly intended to force children to "lead a life different from their parents and cause them to forget the customs, habits & language of their ancestors", to “get rid of the Indian problem.”

Many of these children were abused, not provided enough food or warmth and denied healthcare; many children never came home. We'll never know how many, not for certain. They didn’t see their parents, siblings, cousins, or grandparents again. Their lives were stolen, often ended, because the Canadian government wanted to destroy their culture and didn’t believe they deserved the same human rights as settler Canadian children.

Today - today, right now - some 80% of children in Canadian state custody are Indigenous. There are more Indigenous children in Canada's various child welfare systems today than there were in the Residential Schools system at its peak.

This is not ancient Canadian history. When Netscape Navigator was first released, residential schools in Canada were still operating. This is Canada now, our history and very much our present. For all our talk about what makes Canada different and meaningful, this is also who we are; this is the bedrock Canada was built on.

The introduction to the Truth And Reconciliation Commission's final report concludes that

"... Getting to the truth was hard, but getting to reconciliation will be harder. It requires that the paternalistic and racist foundations of the residential school system be rejected as the basis for an ongoing relationship. Reconciliation requires that a new vision, based on a commitment to mutual respect, be developed. It also requires an understanding that the most harmful impacts of residential schools have been the loss of pride and self-respect of Aboriginal people, and the lack of respect that non-Aboriginal people have been raised to have for their Aboriginal neighbours. Reconciliation is not an Aboriginal problem; it is a Canadian one."

On this wellness week, as we rest and recuperate, consider that Canada Day might be a time, not for celebration, but for reflection, accountability and action. That maybe we can't become the people we say we are, that we could be, without confronting the truth of the people we've been.

Take a moment, on July 1st, to learn the names of Indigenous peoples; find out if you are living on taken land. Take time to learn about issues that Indigenous land stewards, land defenders and activists are engaging with today. Read the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and its Calls to Action, and support the work of Indigenous artists and writers.

Some charities that help survivors of residential schools include https://www.irsss.ca/donate and your local friendship centre (this one is local to the Ottawa area, for example).

If you you'd like to learn more, there are many resources available (credit Creative Mornings Ottawa) including:

Inendi | CBC Short Docs Original by Sarain Fox (Geo-locked to Canadians.)

Settlers Take Action | On Canada Project

“The River, The People and The Industry: The damming history of the Ottawa River Watershed” by Fazeela Jiwa

“Reconciliation Really? A Timeline of the Desecration of Akikodjiwan and Akikpautik, An Anishinaabeg Sacred Place” by Lynn Gehl

Free Indigenous Canada course from U of Alberta

Learn about the land and communities of the land, on which you live.

Algonquin Anishinaabe Land Acknowledgement by Dr. Lynn Gehl, Ph.D., an Algonquin Anishinaabe-kwe from the Ottawa River Valley

We Are All Treaty People by Treaty Education Nova Scotia

We’ll see you after the wellness week,

-Mike, on behalf of #canada

1 note

·

View note

Text

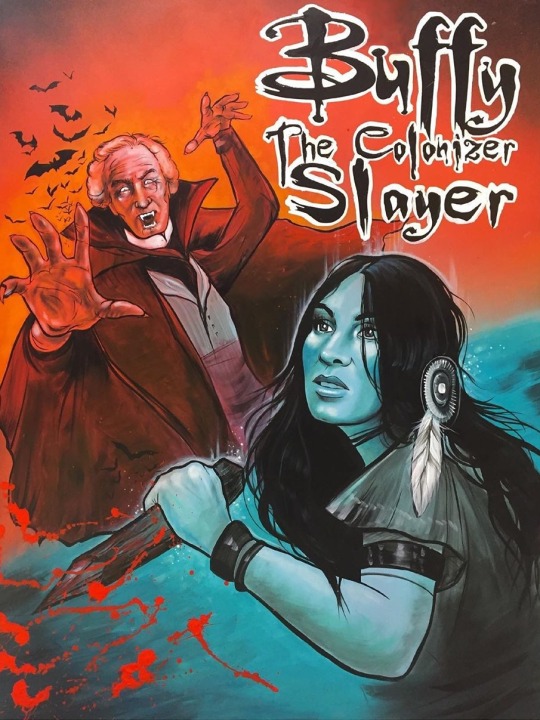

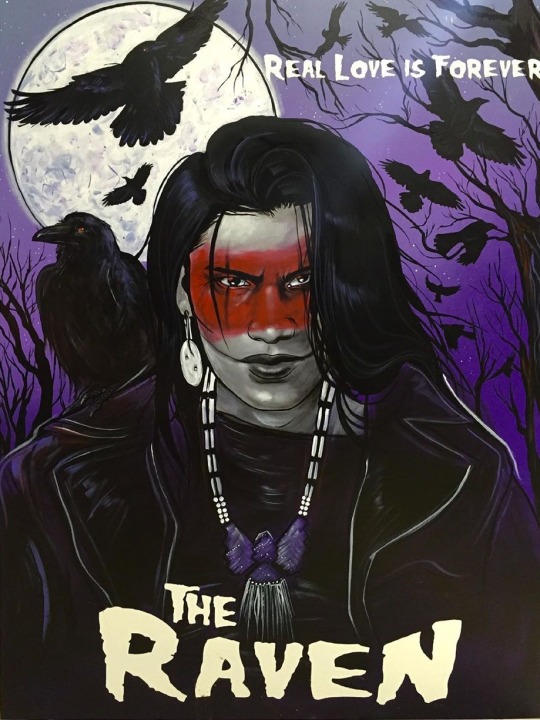

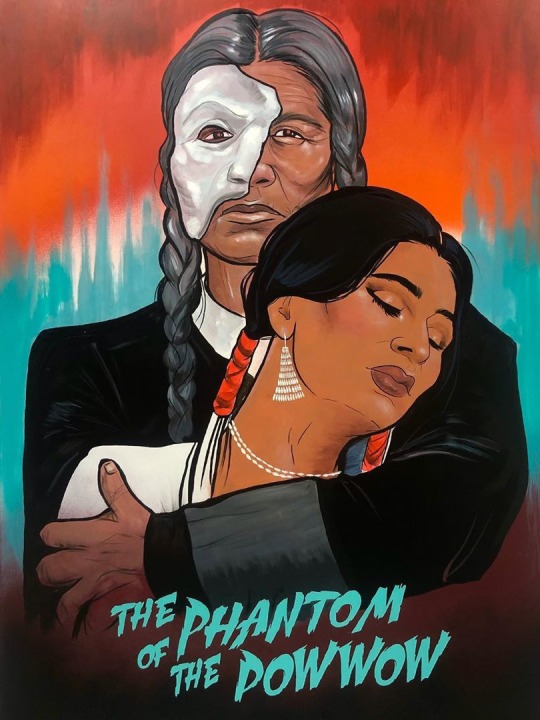

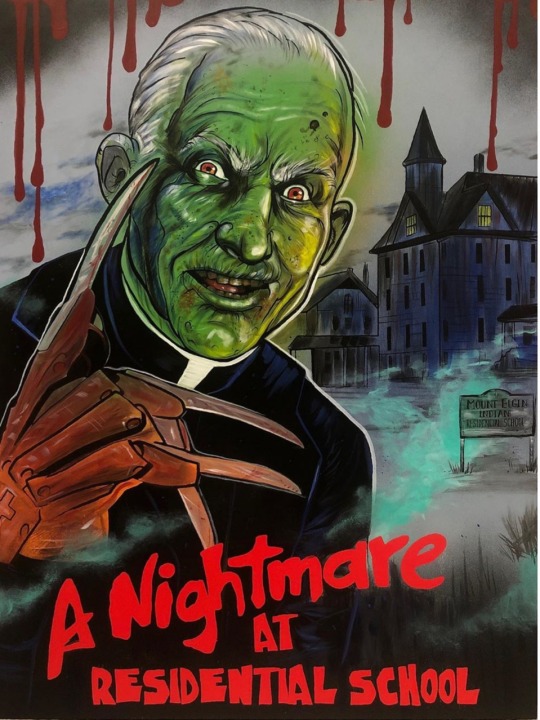

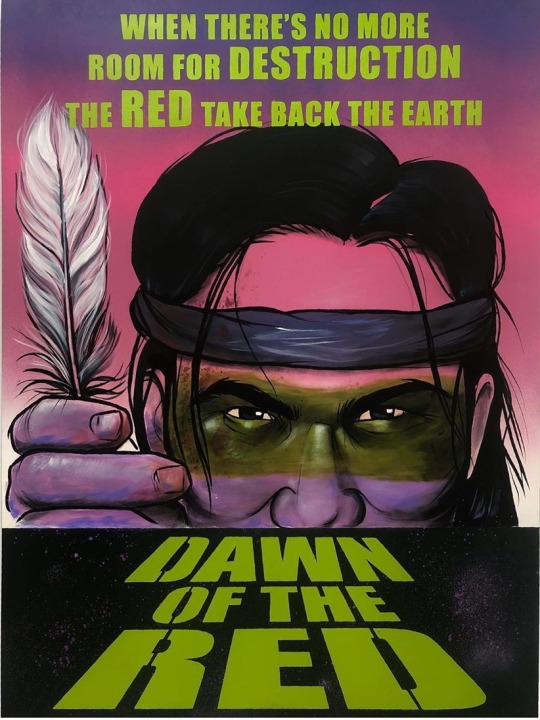

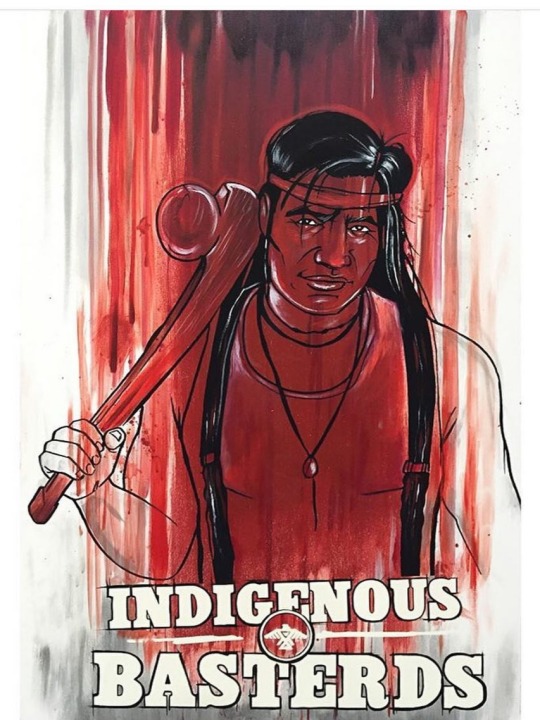

Art by Jay Soule aka Chippewar, a multimedia artist and fashion designer from Chippewas of the Thames First Nation (Deshkaan Ziibing Anishinaabeg) in London, Ontario. IG

🍃

#art#horror movies#indigenous#indigenous art#first nations#native american#native artists#canada#ontario#aesthetic#owl post

27 notes

·

View notes

Link

“Enter a new game: When Rivers Were Trails, a Native-themed decision-based roleplaying video game created with the help of the Indian Land Tenure Foundation and Michigan State University’s Games for Entertainment and Learning Lab and financial support from the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians.

The game came together due to the contributions of indigenous artist Weshoyot Alvitre, 20 indigenous writers, and thematic music by artists Supaman and Michael Charette.

In the game, an Anishinaabeg player in the 1890s is displaced from Fond du Lac in Minnesota due to the impact of land allotments. They make their way to the Northwest and eventually venture into California.

The player, who must first choose a clan with different strengths, must make different choices throughout the game as they come across various indigenous people, animals, plants, and run-ins with Indian agents. In the time period of the game, a difficult time of rapid transition for Native peoples, the writers do not shy from controversial gritty truths involving personal family narratives, tribal stories and the darker sides of history.”

Read the full piece here

491 notes

·

View notes

Photo

DAY 27: Folklore and mythology

This is a touchy subject, especially calling things “folklore and mythology.” Anishinaabe people have a large number of traditional stories, divided into two categories: dibaajimowin and aadizookaan. The first category is for most stories that happened to people you know or can remember, or also for fiction, while the second refers to sacred stories from long ago.

One of the biggest figures of Anishinaabe aadizookaanag is Nenaboozhoo (also spelled Nanabush, Nanabozhoo, Wenabozhoo, Manaboozhoo, and sometimes in the north and far west called Wiisakejaak). He is often called a culture hero or trickster and there are many stories about his adventures. One of the central stories of Anishinaabe people is the story of how the earth was flooded and then remade on the back of a turtle by Nenaboozhoo (or in some versions, Sky Woman), hence why North America is called Turtle Island by some.

Other stories are sometimes about animals and how they came to be certain ways, or about monsters like wiindigos that have troubled people and then been slayed. There are also other beings respected by Anishinaabeg such as memegwesiwag (the little people) and saabe (bigfoot).

(The Twitter icon for National Aboriginal Day designed by Anishinaabe artist Chief Lady Bird | image credit)

Related vocabulary

Nenaboozhoo - Nanabush the trickster/culture hero

memegwesi - the little people

saabe, misaabe - bigfoot

wiindigo - wendigo, cannibal monster

bakaak - skeleton spirit

Mikinaakominis - Turtle Island

Giizhigookwe - Sky Woman

Mizakamigookwe, Shkaakaamikwe - Mother Earth (not a literal translation)

Gookomisinaan - Our Grandmother (refers to the earth or moon)

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

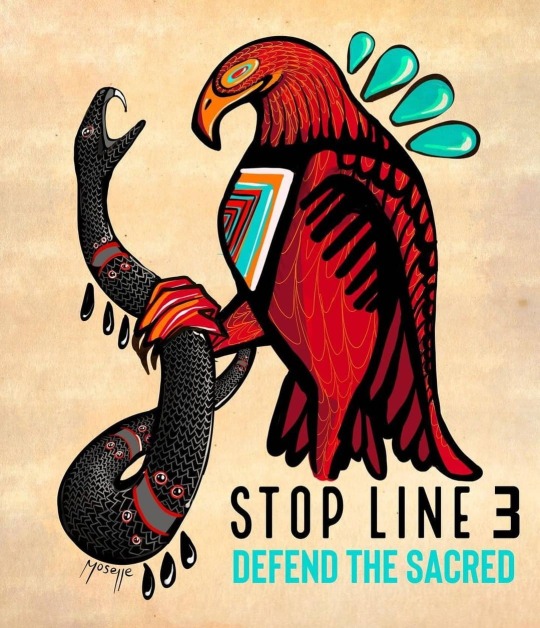

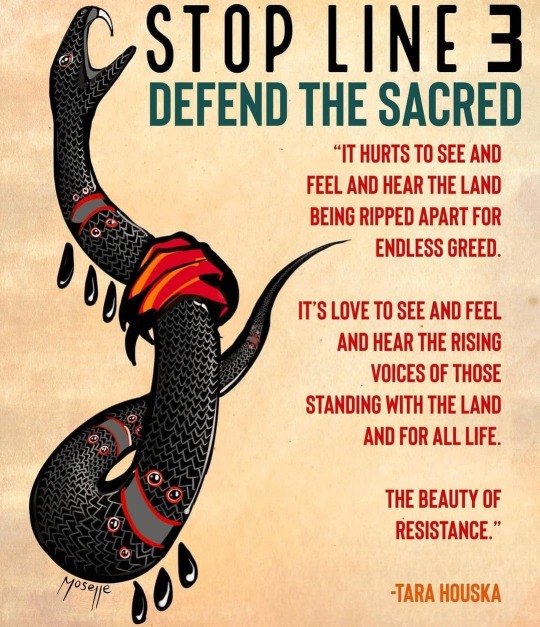

✊🏿🌍💦#ArtIsAWeapon

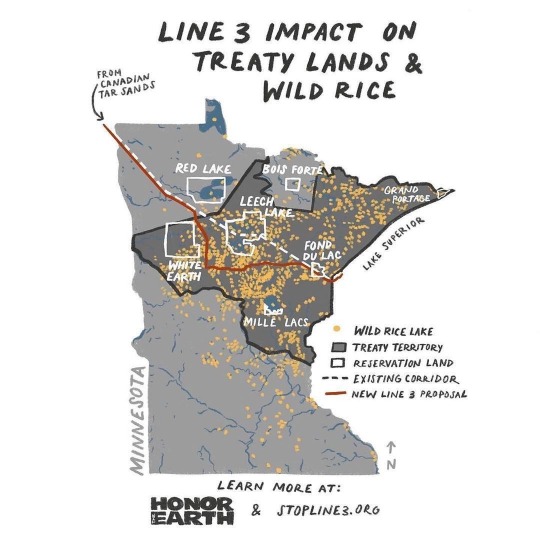

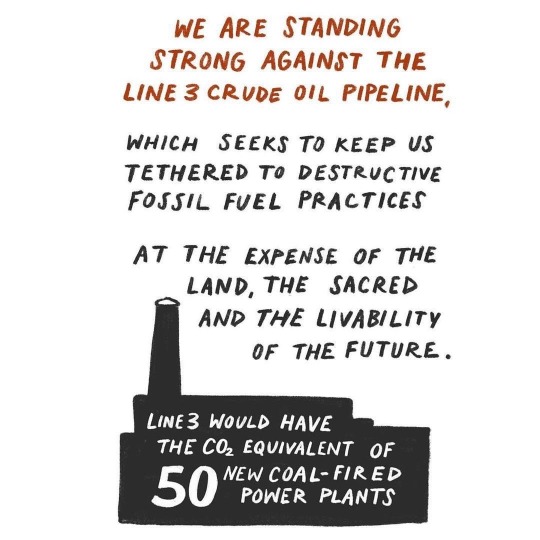

Stop Line 3. Defend the sacred. Swipe ⬅️ to learn more and #takeaction. #WaterIsLife

•

Reposted from @resist_line_3

Now is the time to #StopLine3. The movement is growing. This fight is important. Images by 3-10 by #artist @dioishh

•

Reposted from @lakotalaw If y’all haven’t heard South Dakota legalized lethal force against water Protectors, by privately funded national guard - and #HR1374 would REQUIRE that all states have this policy in place for the sake of “energy security” #StopLine3

Images 1 & 2 by #artist @moselle.singh (reposted) - “It hurts to see and feel and hear the land being ripped apart for endless greed.

It’s love to see and feel and hear the rising voices of those standing with the land and for all life.

The beauty of resistance.”

- @zhaabowekwe (Tara Houska)

Line 3 is a pipeline that is under construction that blatantly violates the treaty rights of the Anishinaabe peoples and will directly impact the wetlands and wild rice grown in those areas. @enbridge is the Canadian pipeline company responsible for this project, and they are also responsible for largest inland oil spill in the US. This expanded pipeline runs from the Mississippi River headwaters to the shore of Lake Superior, disrupting pristine wetlands, woodlands, and Anishinaabe treaty territory.

These pipes WILL inevitably spill into the water and the land, contaminating the soil and water. This will effect the entire Mississippi water way and Lake Superior, the largest fresh water lake in the world.

Please amplify and support the movement to stop Line 3.

Defend the sacred 💜⚔️💜

Consider sharing information, donating, and educating yourselves about what has been going on:

Visit: stopline3.org

Follow: @resist_line_3 @stopline3pipeline @winonaladuke @zhaabowekwe @giniwcollective @nfld.against.line.three @lifewithoutline3 @honortheearth @stopthemoneypipeline @greatplainsactionsociety @justseeds

#stopline3 #noline3 #ln3 #resistline3 #defendthesacred #protecttheearth #art #artactivism #digitalillustration #digitalart #digitalartist #indigenous #womenartists #bipocartists #illustration #amplifierart #artactivist

instagram

0 notes

Text

WINDOW WINNIPEG PRESENTS: WORKSHOP WITH LIZ IKIRIKO

window winnipeg presents A Homemade Practice, a workshop delivered by artist/curator Liz Ikiriko.

Workshop date: Sunday, March 26 1-3pm CDT / 2-4pm EDT

Location: online, via Zoom

Accessibility information: Please contact [email protected] with any access needs.

This workshop is free to attend. Please sign up through our link in bio \\ Please sign up at the following link:

https://www.eventbrite.com/e/a-homemade-practice-tickets-586074754367

~~

Image description: An array of collages is visible. They overlap each other and fill the image. Imagery throughout the collages includes people, a ram, shells, plants, jewellry, roman numerals, and music notes. Visible words among the collages include “The Sun,” “Spellbound,” “New group rules,” “spaciousness,” and “cultivation | cur.”

~~

“What else can you offer the earth, which has everything? What else can you give but something of yourself? A homemade ceremony, a ceremony that makes a home.” - Robin Wall Kimmerer

Hosted by Liz Ikiriko, A Homemade Practice workshop is a practice in breathing, embodied listening, citation, art making and finding ways to cultivate ceremony in the everyday.

Ikiriko will draw on sourcing natural, found materials and the physical act of making as ceremony. Reflecting on numerous artists, writers, and teachers, the workshop will focus on sharing resources for creating a foundational sense of belonging and home in any environment.

The workshop will include a short breathing exercise, meditation, and participants are asked to bring a physical project to work on throughout the online workshop. This could be knitting, collage-making, sewing, painting, etc.

~~

About the artist:

With over fifteen years of experience in the field of contemporary art and photography, and as a Nigerian Canadian mother, maker and curator, Liz Ikiriko has delivered large-scale complex projects working closely with a variety of artists, organizations and institutions, while prioritizing narratives of the African diaspora. Through collaboration and research, she supports and creates embodied experiences to facilitate moments of belonging and care with her communities. She received her MFA in Criticism and Curatorial Practice from OCAD University and has taught photography at Toronto Metropolitan University and Sheridan College; worked on publications including Public Journal, MICE Magazine, Blackflash, Akimbo, C Magazine and most recently contributed to Aperture’s As We Rise: Photography From the Black Atlantic. She is the co-founder of the Ways of Attuning Curatorial Study Group, was a member of the curatorial committee for the 13th Rencontres de Bamako, African Photography Biennial and is the inaugural Curator, Collections and Art in Public Spaces at the Art Museum, University of Toronto.

window is located on Treaty 1 Territory, the original lands of Anishinaabeg, Cree,

Oji-Cree, Dakota, and Dene peoples and the Homeland of the Métis Nation. window is

co-curated by Noor Bhangu, Mariana Muñoz Gomez, and Jennifer Smith.

window acknowledges the support of the Canada Council for the Arts for this programming.

0 notes

Text

Untitled (All Walls Crumble)

The Anishinaabeg endure. We do so through settler colonial time, and across space. We do so in contention. Untitled (All Walls Crumble) considers this movement. To be Indigenous in the city is so often a struggle for recognition, to be seen, and to resist the erasure that is common in Toronto, Montreal, Ottawa, etc. Yet with recognition also comes appropriation and co-optation. In this unease, we consider the benefits of erasure, or at least, covert movement.

Inspired by stories of our relatives and ancestors counting coup, and Basil Johnson’s description of warfare more generally, the Ogimaa Mikana Project considers the tension between visibility and invisibility to challenge settler colonial logic. Against a crumbling wall holding up Ottawa’s major highway - scheduled for demolition and replacement - we draw attention to the ways the settler state recycles itself, and by extension, affirms its legitimacy. We see it and resist in provocative ways that mirror a there/not there presence.

Against this crumbling wall, we reclaim space for an anti-recognition: to speak to each other, as Anishinaabeg, as communities pushed out by gentrification, as the colonized, and offer a refrain and a sign of defiance: "Wakayakoniganag da pangishin. Nin d'akiminan kagige oga ahindanize."

Untitled (All Walls Crumble) is exhibited as part of Language of Puncture, an exhibition curated by visual artist Joi T. Arcand at Gallery 101. Photo courtesy of Gallery 101 and Joi T. Arcand

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some Thoughts on “Magical Realism” and Native American Literature

I’ve been thinking a lot about magic realism as a genre lately and I thought this was interesting. So obviously I adore magic realism as a narrative technique as it blends together these traditionally separate ideas of “realistic fiction” and “fantasy.” But I wanted to look into it a little deeper and after some research, a conversation with my mother, and some contemplation, I had some thoughts about how this idea relates (or doesn’t) to Native American literature.

So historically, magic realism has been a strategy that was largely utilized and popularized by Latin-American writers in the 1940’s and is broadly generalized by “the matter-of-fact inclusion of fantastic or mythical elements into seemingly realistic fiction.” (britannica.com) Which is fantastic. They also write there that “some scholars have posited that magic realism is a natural outcome of postcolonial writing, which must make sense of least two separate realities—the reality of the conquerors as well as that of the conquered.” (britannica.com) I have become increasingly invested in and enthralled by postcolonial and decolonial narratives over the past year and a half and to see that one of my favorite narrative mechanisms was born largely out of the struggle of people of color living in the historical shadow of colonialism was really cool and inspiring.

A few weeks ago I was discussing the aspects of magical realism writing that I found fascinating with my mother after she had just returned from a large conference in Ontario centered around Native/First Nations writing. Now my native heritage comes from my dad’s side, not my mom’s, but as an academic publisher in Michigan, my mom reviews and publishes lots of books by Native authors that center Native issues/narratives (largely Anishinaabeg as we Ojibwe are the people native to the Michigan/Wisconsin/Ontario area.) We discussed how Native fiction authors almost always seem to include some aspect of magic realism in their writings. Even native authors writing non fiction or memoirs seem to draw some of these elements. Therefore, a lot of Native writing (if it ever gets labeled as anything besides simply “Native American literature”) is seen sort of as surreally postmodern or poetic or fantastical. Eventually we discuss that a lot of this is because of the cultural difference between the western American consumers of literature who draw these genre divisions and the cultural beliefs and viewpoints of Native communities. (And here, again, I am speaking mostly about Anishinaabeg because I only belong to the Ojibwe people and can’t speak for the diverse beliefs of the other many and varied peoples native to the Americas.)

The roots of magical realism in Latin America seem to be implementing the seemingly incongruous worlds of magical and mundane blended as a metaphor for the imperfect tension of Latin American countries following a history of colonialism. And while I find this an enthralling artistic expression of the very real struggle of a particular time, place, culture, and ethnic identity, the more I think on it the more I find the application of “magical realism” labels to many Native narratives (specifically the groups of the US and Canada) to be troubling.

The thing is is that, being familiar with Ojibwe belief systems, magical realism only fits these kinds of stories if the label is applied from the outside. Latin American authors combined fantastical elements with detailed realistic aspects metaphorically in order to represent situational struggles. To look at a piece of Native writing and deem that magical realism has been employed as a narrative strategy completely ignores the cultural viewpoint of its cultural origin. To Native people, this “surreal” or “mystical” interpretation of the world is not magical realism, it is just realism.

For example, let’s take a story where the protagonist asks the ghosts of their grandma and great-grandpa for career advice, where they make a necklace from an eagle feather to grant them protection from corrupt police, where they burn offerings to a thunderstorm after a stretch without rain. If you looked at this story from a Western perspective, you would indeed label it magical realism because we consider some of the things to be realistic—asking advice in the face of career uncertainty, police corruption, summer droughts—and some to be magical—speaking to ghosts, jewelry possessing power, thunderstorms having the sentience to receive thanks. However, if you read this same story through the lens of an Ojibwe belief system, there is nothing inherently unrealistic about it. In the Ojibwe tradition, the belief that our ancestors are always with us and come to help guide us is commonplace and accepted. If you ask the spirit that lives inside of an eagle feather for its help and burn tobacco in its honor, a necklace including that would indeed be powerful because it is accepted that spirits inhabiting eagle feathers are very powerful things and spirits are willing to aid Anishinaabeg if one asks in the correct, humble way. And in the old stories, thunderstorms are said to be huge spirit creatures called animikiig or “thunderbirds” and to offer them tobacco is a way of thanking them for the rain they bring to help the growing things. If you read these stories from a place of accepting a cultural/spiritual truth of Native (here specifically Anishinaabe) worldviews, then it is no longer “magical realism.”

In the Latin American tradition, the magical elements of magical realism combined with the world as we know it are metaphorical. In Native stories, often these kinds of things are metaphors but they are not exclusively metaphorical. They are aspects that simultaneously truly exist in the world as accepted from this belief system and can be used as a metaphor as well (just as any object or person in traditional realistic western literature.) Now this is not to say every author of native descent who employs these features in their writing subscribes to or practices their tribe’s traditional spiritual beliefs, nor do I think they have to in order to honor the validity and truth of their culture’s spiritual beliefs and traditions. The point here, I think, is that these stories themselves should be viewed from the cultural viewpoint and that our western ideas of what constitutes “realistic” and what constitutes “magical” don’t necessarily apply to many of the narratives that come out of Native communities and Native authors.

I’ve just been thinking about this a lot and how easily many Native narratives and works of fiction can be misconstrued, especially when they incorporate aspects of traditional beliefs. I think readers need to be careful when reading these things not to fall into this trap of thinking “oooh, look at this creative mystical Indian writer who is so in tune with nature woww what a magical connection with the earth” because that’s a hella racist stereotype. (Look up the “Magical Native American” on TVTropes.) Native stories can and do often depict gritty realistic portrayals of life on reservations, of rampant alcohol abuse, of poverty in inner city communities, of racism, etc. But I think that it’s a problem that when Native authors include (as many do in their life and beliefs) traditional spiritual aspects to their narratives they become seen as “fantastical” and “unrealistic.” Because to many Native communities, this simultaneous existence of modern day Native struggles AND connection to ancestors or participation in ceremonies or offering tobacco to the spirits to help you with a job interview is a very real thing.

19 notes

·

View notes