#and with valjean it was champmathieu being tried as him

Text

Jonathan Harker 🤝 Jean Valjean

Hair turning white after a dramatic moment

#and both due to something happening to someone else#rather than themselves#with jonathan it was dracula attacking mina#and with valjean it was champmathieu being tried as him#dracula daily#les miserables#jonathan harker#jean valjean

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m not coherent but there’s something fascinating about the way Javert’s inability to lie goes from being a source of strength to a source of deep vulnerability.

In earlier chapters Javert’s honesty grants him confidence and strength:

“He raised his head with the intrepid serenity of a man who has never lied.”

But after the barricades, his inability to lie makes him vulnerable around Jean Valjean— he struggles to lie to him and conceal how much he’s affected him, unable to confess his emotions to Jean Valjean because he can’t confess them to himself.

He tries to pretend nothing has changed between himself and Jean Valjean, but refers to Jean Valjean with the formal “you” without being aware of it. He gets instantly emotional the moment he recognizes Jean Valjean outside the sewers, in a way that he was not when he recognized Jean Valjean at the barricades. He tries to lie that he will wait for Jean Valjean in the street and be there to arrest him, but telling that lie seems to physically pain him, and Jean Valjean almost doesn’t believe him:

He added with a strange expression, and as though he were exerting an effort in speaking in this manner:

“I will wait for you here.”

Jean Valjean looked at Javert. This mode of procedure was but little in accord with Javert’s habits.

There’s a line in his resignation in Montreuil sur Mer that describes Javert’s eyes as being so clear that you can see all the way down to the very bottom of his conscience— which is so funny to me. That is a TERRIBLE trait for a police spy. Being so honest that people can see your entire soul is a HORRIBLE spy trait. Who made this man a spy. Who sent him to the barricades.

There’s a weird paradox to Javert’s honesty. He is a “mouchard”/police spy who uses the word “mouchard” as an insult, to describe the kind of liar he doesn’t want to be— and whose coworkers have to carefully leave him out of their corruption schemes because he wouldn’t stand any kind of dishonesty. At the barricades he’s easily captured after revealing his full name address and social security number to a question a better spy could’ve lied their way out of. He’s just not willing to lie, at all, for any reason— even though it’s his job. When he has to follow orders, he’ll gaslight himself into believing incorrect information (ex. “Champmathieu is Valjean”) rather than lie.

Post-barricades Javert is the only time we *really* see Javert struggling to lie to someone else that he feels things he does not feel, and believes things he does not believe…and it’s kinda endearing how he’s so bad at it. He sucks at it a lot.

And that’s just really fascinating, as a character note?

Javert never lied because he was always “irreproachable,” and felt that he had nothing to hide. Whenever he did commit infractions, he would honestly confess his failures and demand punishment. He’s always been stoic and calm, but he’s also always been so transparently honest you can see to the bottom of his conscience.

But when he’s no longer “irreproachable,” and when has things to hide— his honesty becomes this weird source of vulnerability.

#les mis#inspector javert#is this coherent?? idk#but yeee#poor angry brick of a man#les mis letters#lm 4.8.11

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

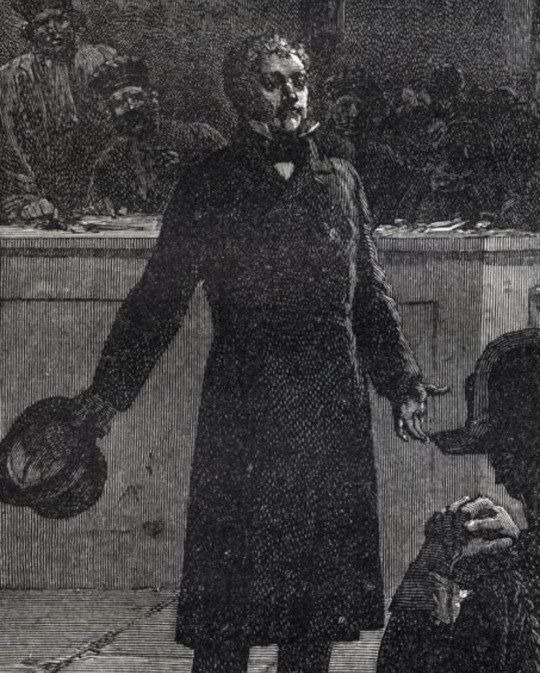

Jean Valjean speaks!

I honestly feel excited every time I see a block paragraph that’s just him talking because we so rarely hear things from his perspective. The latter half of his speech really reminds me of the nettle speech, but in a personal way; rather than a plant becoming dangerous when neglected, Valjean notes that he himself became “vicious” because of the abuses he endured, and that kindness was what allowed him to recover. He states that his condition was not entirely his fault, again recognizing how these systems not only harmed him during and after his imprisonment, but how they set him up for failure in the first place. It’s also interesting that he narrates all of this in the past tense, acknowledging that while he is Valjean in name, the character of Valjean as described at the trial (by both the prosecutor and himself) is quite distinct from who he is today. He’s aware of how much he’s changed.

At the same time, he doesn’t really feel that he can become part of society again. He says:

“I have tried to re-enter the ranks of the honest. It seems that that is not to be done.”

On the one hand, this is a reasonable thing to say at his own trial, which he knows is more on the basis of his identity than the crime Champmathieu is accused of. It’s strange of him to separate himself from “the honest” when he’s the most honest person here - he’s turning himself in and presenting evidence against himself, even wishing the one person who could identify him was present - but he realizes that he won’t be treated as “honest” no matter what he does. On the other, it reflects the persistent gap he perceives between himself and everyone else. In Montreuil-sur-Mer, for instance, he was very isolated in spite of his popularity. Again, his need to conceal his identity contributed to this, but it also indicates how he’s constantly distancing himself from others even as he serves this goal of “honesty.” He can behave as honestly as possible, but he never allows himself to fully rejoin “their ranks” because he doesn’t truly feel as though he’s a part of them.

Spoilers below:

This particularly reminds me of how Valjean distances himself from Cosette at the end of the novel. He returns to considering himself a criminal who cannot “re-enter the ranks of the honest” because “that is not to be done,” so he “has” to remove himself from her life to guarantee her happiness. He again combines legitimate concerns (risking imprisonment if someone discovers his identity) with his self-hatred (making himself suffer by distancing himself from his daughter). This later instance is distinct, of course, in that it’s directly harmful to those around him. In Champmathieu’s case, the people of Montreuil-sur-Mer may suffer if Valjean turns himself in, but that’s mainly due to his position as mayor, and he also does have some level of responsibility for a man being tried under his name. However, with Cosette, he’s just confusing and scaring her without her having any context for his behavior, and he himself is acting on fear, self-doubt, and self-loathing, taking precautions that may not be needed.

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Started watching I Mis 1948 today, and it is. A RIDE.

It starts with Valjean stealing the bread , at which point he is SHOT , apparently to no ill effect, since he's then put to work, shirtless and unmarked, in the galleys

which he tries to escape with an EXPLOSION and STEALING A RAIL CART that he CRASHES INTO A BARRIER before swinging down a cliff and onto horseback!! whence he rushes off again! and is shot AGAIN and the horse...dies?? but NOT HIM

then he leads a prison revolt!!

Unfortunately once he's released, he's rather dull as Valjeans go--the actor basically didn't WANT to play Valjean, with all his inner turmoil, he wanted to be a Dashing Hero!-- to the point that he refused to wear torn clothes, afraid it would ruin his Image to be seen in rags.

(the clothes throughout are pretty good! not Gentleman Jack level maybe, but solidly recognizable for the period. They even give the women bonnets! and period-reasonable hairstyles!)

Javert is also tragically Meh, no menace or sense of presence at all, really; he WOULD be very plausible at being in disguise because even in uniform it's easy to miss that he's there :/

The best part of this adaptation so far is how it handles Fantine's storyline--we see her fired (for always being late , because she's ...going to visit Cosette on weekends??? I am hoping SO HARD that that will pay off in an altered story, I don't need canon faithfulness in this movie, Fantine Be Happy AU ) , and then cut to her walking the street and having her fight with Bamatabois; from there, Valjean steps in--

and then FANTINE GETS TO TELL US HER BACKSTORY, with her own interpretation of it! We get a lovely 1817 flashback, we get to here her sorrow and her determination FROM HER, she gets to take the starring role in her own story and even if the movie screws up everything from this point on, I love it for that.

anyway like I said, most of the Valjean story is pretty Meh, rote stuff performed at an OK level, but we DO get to see Valjean, in his turmoil over Champmathieu, consult his Spiritual Adviser:

SISTER SIMPLICE, SCIENCE NUN!!

(seriously, she DOES take on a more active role in this as his spiritual adviser AND a real medical scientist AND she gets to talk about her faith a little?? this version is doing great by the women in it so far)

ANYWAY that's the first hour of this series gone by and we haven't even had the trial so I have no idea how this is gonna go

We await the results of the Experiment!

#I Mis 1948#SCIENCE SIMPLICE#this moves fasters than a lot of them and the set and costumes are great#and I really do love Fantine#there's a Baptistine too!!!#LM 1948

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Place Where Convictions Are In Process Of Formation

Volume 1: Fantine; Book 7: The Champmathieu Affair; Chapter 9: A Place Where Convictions Are In Process Of Formation

He advanced a pace, closed the door mechanically behind him, and remained standing, contemplating what he saw.

It was a vast and badly lighted apartment, now full of uproar, now full of silence, where all the apparatus of a criminal case, with its petty and mournful gravity in the midst of the throng, was in process of development.

At the one end of the hall, the one where he was, were judges, with abstracted air, in threadbare robes, who were gnawing their nails or closing their eyelids; at the other end, a ragged crowd; lawyers in all sorts of attitudes; soldiers with hard but honest faces; ancient, spotted woodwork, a dirty ceiling, tables covered with serge that was yellow rather than green; doors blackened by handmarks; tap-room lamps which emitted more smoke than light, suspended from nails in the wainscot; on the tables candles in brass candlesticks; darkness, ugliness, sadness; and from all this there was disengaged an austere and august impression, for one there felt that grand human thing which is called the law, and that grand divine thing which is called justice.

No one in all that throng paid any attention to him; all glances were directed towards a single point, a wooden bench placed against a small door, in the stretch of wall on the President’s left; on this bench, illuminated by several candles, sat a man between two gendarmes.

This man was the man.

He did not seek him; he saw him; his eyes went thither naturally, as though they had known beforehand where that figure was.

He thought he was looking at himself, grown old; not absolutely the same in face, of course, but exactly similar in attitude and aspect, with his bristling hair, with that wild and uneasy eye, with that blouse, just as it was on the day when he entered D——, full of hatred, concealing his soul in that hideous mass of frightful thoughts which he had spent nineteen years in collecting on the floor of the prison.

He said to himself with a shudder, “Good God! shall I become like that again?”

This creature seemed to be at least sixty; there was something indescribably coarse, stupid, and frightened about him.

At the sound made by the opening door, people had drawn aside to make way for him; the President had turned his head, and, understanding that the personage who had just entered was the mayor of M. sur M., he had bowed to him; the attorney-general, who had seen M. Madeleine at M. sur M., whither the duties of his office had called him more than once, recognized him and saluted him also: he had hardly perceived it; he was the victim of a sort of hallucination; he was watching.

Judges, clerks, gendarmes, a throng of cruelly curious heads, all these he had already beheld once, in days gone by, twenty-seven years before; he had encountered those fatal things once more; there they were; they moved; they existed; it was no longer an effort of his memory, a mirage of his thought; they were real gendarmes and real judges, a real crowd, and real men of flesh and blood: it was all over; he beheld the monstrous aspects of his past reappear and live once more around him, with all that there is formidable in reality.

All this was yawning before him.

He was horrified by it; he shut his eyes, and exclaimed in the deepest recesses of his soul, “Never!”

And by a tragic play of destiny which made all his ideas tremble, and rendered him nearly mad, it was another self of his that was there! all called that man who was being tried Jean Valjean.

Under his very eyes, unheard-of vision, he had a sort of representation of the most horrible moment of his life, enacted by his spectre.

Everything was there; the apparatus was the same, the hour of the night, the faces of the judges, of soldiers, and of spectators; all were the same, only above the President’s head there hung a crucifix, something which the courts had lacked at the time of his condemnation: God had been absent when he had been judged.

There was a chair behind him; he dropped into it, terrified at the thought that he might be seen; when he was seated, he took advantage of a pile of cardboard boxes, which stood on the judge’s desk, to conceal his face from the whole room; he could now see without being seen; he had fully regained consciousness of the reality of things; gradually he recovered; he attained that phase of composure where it is possible to listen.

M. Bamatabois was one of the jurors.

He looked for Javert, but did not see him; the seat of the witnesses was hidden from him by the clerk’s table, and then, as we have just said, the hall was sparely lighted.

At the moment of this entrance, the defendant’s lawyer had just finished his plea.

The attention of all was excited to the highest pitch; the affair had lasted for three hours: for three hours that crowd had been watching a strange man, a miserable specimen of humanity, either profoundly stupid or profoundly subtle, gradually bending beneath the weight of a terrible likeness. This man, as the reader already knows, was a vagabond who had been found in a field carrying a branch laden with ripe apples, broken in the orchard of a neighbor, called the Pierron orchard. Who was this man? an examination had been made; witnesses had been heard, and they were unanimous; light had abounded throughout the entire debate; the accusation said: “We have in our grasp not only a marauder, a stealer of fruit; we have here, in our hands, a bandit, an old offender who has broken his ban, an ex-convict, a miscreant of the most dangerous description, a malefactor named Jean Valjean, whom justice has long been in search of, and who, eight years ago, on emerging from the galleys at Toulon, committed a highway robbery, accompanied by violence, on the person of a child, a Savoyard named Little Gervais; a crime provided for by article 383 of the Penal Code, the right to try him for which we reserve hereafter, when his identity shall have been judicially established. He has just committed a fresh theft; it is a case of a second offence; condemn him for the fresh deed; later on he will be judged for the old crime.” In the face of this accusation, in the face of the unanimity of the witnesses, the accused appeared to be astonished more than anything else; he made signs and gestures which were meant to convey No, or else he stared at the ceiling: he spoke with difficulty, replied with embarrassment, but his whole person, from head to foot, was a denial; he was an idiot in the presence of all these minds ranged in order of battle around him, and like a stranger in the midst of this society which was seizing fast upon him; nevertheless, it was a question of the most menacing future for him; the likeness increased every moment, and the entire crowd surveyed, with more anxiety than he did himself, that sentence freighted with calamity, which descended ever closer over his head; there was even a glimpse of a possibility afforded; besides the galleys, a possible death penalty, in case his identity were established, and the affair of Little Gervais were to end thereafter in condemnation. Who was this man? what was the nature of his apathy? was it imbecility or craft? Did he understand too well, or did he not understand at all? these were questions which divided the crowd, and seemed to divide the jury; there was something both terrible and puzzling in this case: the drama was not only melancholy; it was also obscure.

The counsel for the defence had spoken tolerably well, in that provincial tongue which has long constituted the eloquence of the bar, and which was formerly employed by all advocates, at Paris as well as at Romorantin or at Montbrison, and which to-day, having become classic, is no longer spoken except by the official orators of magistracy, to whom it is suited on account of its grave sonorousness and its majestic stride; a tongue in which a husband is called a consort, and a woman a spouse; Paris, the centre of art and civilization; the king, the monarch; Monseigneur the Bishop, a sainted pontiff; the district-attorney, the eloquent interpreter of public prosecution; the arguments, the accents which we have just listened to; the age of Louis XIV., the grand age; a theatre, the temple of Melpomene; the reigning family, the august blood of our kings; a concert, a musical solemnity; the General Commandant of the province, the illustrious warrior, who, etc.; the pupils in the seminary, these tender levities; errors imputed to newspapers, the imposture which distills its venom through the columns of those organs; etc. The lawyer had, accordingly, begun with an explanation as to the theft of the apples,—an awkward matter couched in fine style; but Bénigne Bossuet himself was obliged to allude to a chicken in the midst of a funeral oration, and he extricated himself from the situation in stately fashion. The lawyer established the fact that the theft of the apples had not been circumstantially proved. His client, whom he, in his character of counsel, persisted in calling Champmathieu, had not been seen scaling that wall nor breaking that branch by any one. He had been taken with that branch (which the lawyer preferred to call a bough) in his possession; but he said that he had found it broken off and lying on the ground, and had picked it up. Where was there any proof to the contrary? No doubt that branch had been broken off and concealed after the scaling of the wall, then thrown away by the alarmed marauder; there was no doubt that there had been a thief in the case. But what proof was there that that thief had been Champmathieu? One thing only. His character as an ex-convict. The lawyer did not deny that that character appeared to be, unhappily, well attested; the accused had resided at Faverolles; the accused had exercised the calling of a tree-pruner there; the name of Champmathieu might well have had its origin in Jean Mathieu; all that was true,—in short, four witnesses recognize Champmathieu, positively and without hesitation, as that convict, Jean Valjean; to these signs, to this testimony, the counsel could oppose nothing but the denial of his client, the denial of an interested party; but supposing that he was the convict Jean Valjean, did that prove that he was the thief of the apples? that was a presumption at the most, not a proof. The prisoner, it was true, and his counsel, “in good faith,” was obliged to admit it, had adopted “a bad system of defence.” He obstinately denied everything, the theft and his character of convict. An admission upon this last point would certainly have been better, and would have won for him the indulgence of his judges; the counsel had advised him to do this; but the accused had obstinately refused, thinking, no doubt, that he would save everything by admitting nothing. It was an error; but ought not the paucity of this intelligence to be taken into consideration? This man was visibly stupid. Long-continued wretchedness in the galleys, long misery outside the galleys, had brutalized him, etc. He defended himself badly; was that a reason for condemning him? As for the affair with Little Gervais, the counsel need not discuss it; it did not enter into the case. The lawyer wound up by beseeching the jury and the court, if the identity of Jean Valjean appeared to them to be evident, to apply to him the police penalties which are provided for a criminal who has broken his ban, and not the frightful chastisement which descends upon the convict guilty of a second offence.

The district-attorney answered the counsel for the defence. He was violent and florid, as district-attorneys usually are.

He congratulated the counsel for the defence on his “loyalty,” and skilfully took advantage of this loyalty. He reached the accused through all the concessions made by his lawyer. The advocate had seemed to admit that the prisoner was Jean Valjean. He took note of this. So this man was Jean Valjean. This point had been conceded to the accusation and could no longer be disputed. Here, by means of a clever autonomasia which went back to the sources and causes of crime, the district-attorney thundered against the immorality of the romantic school, then dawning under the name of the Satanic school, which had been bestowed upon it by the critics of the Quotidienne and the Oriflamme; he attributed, not without some probability, to the influence of this perverse literature the crime of Champmathieu, or rather, to speak more correctly, of Jean Valjean. Having exhausted these considerations, he passed on to Jean Valjean himself. Who was this Jean Valjean? Description of Jean Valjean: a monster spewed forth, etc. The model for this sort of description is contained in the tale of Théramène, which is not useful to tragedy, but which every day renders great services to judicial eloquence. The audience and the jury “shuddered.” The description finished, the district-attorney resumed with an oratorical turn calculated to raise the enthusiasm of the journal of the prefecture to the highest pitch on the following day: And it is such a man, etc., etc., etc., vagabond, beggar, without means of existence, etc., etc., inured by his past life to culpable deeds, and but little reformed by his sojourn in the galleys, as was proved by the crime committed against Little Gervais, etc., etc.; it is such a man, caught upon the highway in the very act of theft, a few paces from a wall that had been scaled, still holding in his hand the object stolen, who denies the crime, the theft, the climbing the wall; denies everything; denies even his own identity! In addition to a hundred other proofs, to which we will not recur, four witnesses recognize him—Javert, the upright inspector of police; Javert, and three of his former companions in infamy, the convicts Brevet, Chenildieu, and Cochepaille. What does he offer in opposition to this overwhelming unanimity? His denial. What obduracy! You will do justice, gentlemen of the jury, etc., etc. While the district-attorney was speaking, the accused listened to him open-mouthed, with a sort of amazement in which some admiration was assuredly blended. He was evidently surprised that a man could talk like that. From time to time, at those “energetic” moments of the prosecutor’s speech, when eloquence which cannot contain itself overflows in a flood of withering epithets and envelops the accused like a storm, he moved his head slowly from right to left and from left to right in the sort of mute and melancholy protest with which he had contented himself since the beginning of the argument. Two or three times the spectators who were nearest to him heard him say in a low voice, “That is what comes of not having asked M. Baloup.” The district-attorney directed the attention of the jury to this stupid attitude, evidently deliberate, which denoted not imbecility, but craft, skill, a habit of deceiving justice, and which set forth in all its nakedness the “profound perversity” of this man. He ended by making his reserves on the affair of Little Gervais and demanding a severe sentence.

At that time, as the reader will remember, it was penal servitude for life.

The counsel for the defence rose, began by complimenting Monsieur l’Avocat-General on his “admirable speech,” then replied as best he could; but he weakened; the ground was evidently slipping away from under his feet.

0 notes

Text

Les Misérables 60/365 -Victor Hugo

51

In this town, the young men spend fifteen hundred francs the same as one in Paris spends three hundred thousand. “grow old as dullards, never work, serve no use, and do no great harm.”p.130 If Felix stayed out of Paris, he would have been one. The richer are dandies, (a man devoted to style) the poorer are idles among the unemployed, bored and dreamers. In January of 1823 one of these dandies bowed to each lady, he saw in the street and told the one with no teeth to get out of his face. (as we see style is to compensate for lack of character) As her back was turned, he put snow down her dress and on instinct she turned to attack him, Javert seized Fantine and the dandy took the moment to escape.

52

Javert dragged Fantine to the police station, “This class of woman is consigned by our laws entirely so the discretion of the police. The latter do what they please, punish them, as seems good to them, and confiscate at their will those two sorry things which they entitle their industry and their liberty.”p.131 Javert wrote his report, entering judgment of condemnation. He sentenced her to six months and wouldn’t have sympathy as she cried and pleaded how she would earn money to send to her daughter, how she defended herself. (the law has always been biased against the lower class and ill reputed haven’t they)

A few minutes earlier, a man entered but no one paid him attention, he heard Fantine’s pleas. He stopped the soldiers from taking her and Madeliene orders Javert to let Fantine go but Fantine spat in his face. He wasn’t fazed and Fantine calls him a monster that caused all her suffering by dismissing her from the factory. Then tells Javert how he wronged her before taking her leave since she’s free to go. Javert exasperated at the audacity of it all tries to talk sense into Madeliene but he quotes the law, Javert is out of bounds and Fantine watched them as if they held a combat for her and her child’s life, Madeliene saved her. Her hatred crumbled and he apologized for being ignorant of her and he’ll handle everything and she was overwhelmed she collapsed.

BOOK SIXTH JAVERT

53

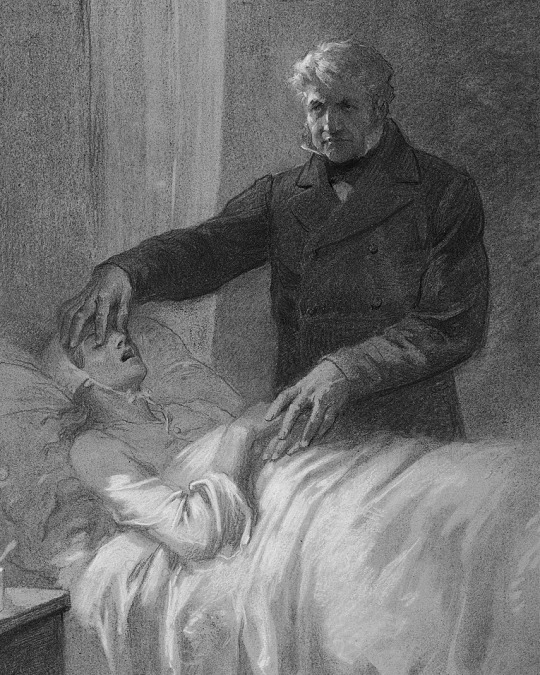

Madeliene had Fantine taken to the infirmary in his house, she became lucid the next morning as Madeliene is praying for martyrs on high and below. He learned about her plight and paid off her debts and had a letter sent to fetch Cosette but Thenardier won't let the cash cow go and rises the price. In this time Fantine didn't recover as the nuns grew softer to her as she wanted her child by her as God’s pardon. As weeks passed, Cosette didn’t come as she wasted and got worse and the doctor said if she’s to see her daughter, make haste to get her. Thenardier still didn’t let her go saying she was too sick to travel and Madeliene made up his mind to get her himself but something came up. (as it always does)

54

As Madeliene was in his office Javert appeared, having gone through a struggle internally over Madeliene. With genuine humility, Javert confessed to feeling in respect towards him, so his duty is to be dismissed. Six weeks ago, after that scene with Fantine. he informed against him to a Prefecture in Paris as an ex-convict Jean Valjean, who disappeared after robbing a Savoyard. The real Valjean had been found, a Father Champmathieu was arrested for robbery and an inmate recognized him as Valjean, enough circumstantial evidence.

Of course, Champmathieu denies he is Valjean for a lesser sentence than life in the galleys, he’s will go to trial as a witness. Madeliene tells him there is other business and police regulations he must do and finds out the date for the trial. He won't dismiss Javert over is mistake but Javert says he’s been so severe as to denounce a respectable man, if he wasn’t severe to himself all his justice will be undone. He doesn’t deserve kindness, he deserves to be made an example of, but will serve until he is replaced. (you know I could make a joke here but I’m just amazed a cop is taking accountably even if he is a fictional one)

BOOK SEVENTH THE CHAMPMATHIEU AFFAIR

55

After Javert’s visit. Madeliene went to visit Fantine and keeps assuring her Cosette will be there soon. The doctor warned him she doesn’t have much time. Back in his office, he marked a road map of France.

56

He went to someone to get a horse and cabriolet for the trip when asked where he’s going Madeliene just repeats the time to show up. Madeliene leaves insurance for the horse and cabriolet, more than they are worth. At home, his cashier listened to his nervous pacing all night.

57

Of course, you already know Madeliene is Valjean (not like it was hard to infer it) and what happened after Gervais, he became a totally different man as the Bishop wished. He sold the silver and wandered from town to town where he settled and established the factory and lived in peace. Until Javert, then his first thought was to denounce himself, but then decided to wait and see. “He repressed this first, generous instinct, and recoiled before heroism.”p.150 It would have been beautiful after the Bishop’s words, but it wasn’t so. (well we need conflict)

At Fantine’s bed he had a vague feeling he must go to Arras and went about his day until he was home, riddled with anxiety. He deluded himself in solitude, did Champmathieu really resemble him, how will it end, what can be done. Gradually, over hours, he came to an answer. He knew hearing that name would cause his new life to vanish and there, God gave him the opportunity to have, Madeliene be more respectable. His place in the galleys was waiting for him that Champmathieu would take. Javert had hunted him but was thrown off, does he have a right to disarrange fate, it is God who wills it so he can continue to do good.

But he continued to ask himself and confessed that it was monstrous to do nothing. He was reopening a door to his past, morally murdering a wretched man, feeling the Bishop was there he had to go to Arras. “He would enter into sanctity only in the eyes of God when he returned to infamy in the eyes of man.”p.154 He makes preparations and letters, the concealment of his name, his life, so distinct they separated into light and darkness antagonistic but good was gaining the upper hand. The Bishop was the first phase of his life, Champmathieu is the second. Tried to reason that Champmathieu isn’t totally innocent, but the heroism of his deed might be taken into consideration and the last seven years, (there was a news story years ago that a guy that was supposed to be in prison for ten years was never taken to prison and the judge let him go because he reformed himself) but it was the theft of Gervais that put him here.

He detached himself that he must do his duty, if he did nothing his good works would be tainted with crime. “virtue without and abomination within, or holiness within and infamy without.”p.155 He had resolved against himself but then remembered Fantine and what would happen to the town and people he’s provided for, it would all die. (pay attention to this) And the child, if the mother dies what would become of her. Champmathieu goes to prison guilty of theft and he remains doing more good.

He believes he is right to stay Madeliene, claim nothing of Valjean, he’s another man now. He opened a secret compartment where lay his old clothes, recognizable to those that saw Valjean at Digne, he had saved the candlesticks. He threw all into the fire that still held a piece of Valjean. A voice seemed to say forget the Bishop, forget everything, destroy Champmathieu’s, enrich the town as Madeliene. (is this an angel demon thing)

His conscience seemed to speak to him, he put the candlesticks back on the mantlepiece. He paced around the room, two ideas, stay silent or denounce himself, he should never be free or loved again, stay in paradise a demon, go to hell as an angel. What should he do, whatever the choice something in him will die.

58

He paced for five hours until he collapsed in a chair and had a nightmare he was with his brother from childhood along a road where everything was dirt colored, his brother was no longer with him in Romainville. He went into an empty house there was a silent man everywhere he went. In the fields he saw a crowd following him and one told him he is dead. (this just reminded me of those Arthur problem solving dream sequences) He woke up then as his horse and cabriolet arrived.

59

Any mail from Arras sent at one at night would arrive in the town by five in the morning. A man drove faster than the mail wagon, he was going to Arras as something urged him forward with no plan. He would prefer not to go to Arras where there was Javert and two convicts who could identify him, but he was going. At the stop in Hesdin the wheel was damaged and the wheelwright can't have it fixed until tomorrow. He can borrow an old calash but no horses to pull it or ride.

Madeliene felt Providence was intervening in his continuing the journey, if he didn’t make it, it wasn’t his fault. Since Javert’s visit the iron hand that held his heart let go. If his conversation with the wheelwright taken place in private no one would have overheard him, but it was in the street and attracted a crowd. A young boy heard and ran off and returned with an old woman who offered to help and the iron hand returned. (could you make a case that the devil is giving him obstacles to give up and God is going him opportunities to continue)

She had a worn-out spring cart but it could get to Arras and he paid to resume on the road. He admitted when the cart moved, he felt joy and found it absurd that he should feel that at turning back on a willing journey. As he left the boy stooped him as he wasn’t paid for his service but Madeliene sped off leaving him nothing. (douche at least toss him a coin) He already lost time in Hesdin and the roads were bad in February.

He stopped again in Saint-Pol four hours later, another hour he was at Tinques, five more leagues (a league is about 3.4 miles) until Arras. His horse was starting to tire as someone told him Arras was seven more leagues away because of road repair. He got directions and a new horse but at the crossroads his cart broke and twenty minutes and a DIY repair later he was at a gallop. Another hour he’ll reach Arras by eight and he didn’t know the hour for the trial. (seems like something you should have found out)

60

Fantine awoke joyful, she had a good dream as she was delirious and the doctor ordered to be informed the moment Madeliene came back. A few months before Fantine was a shadow of herself, illness improvises old age. “Physical suffering had completed the work of moral suffering.”p.170 As the time Madeliene’s visits approached, he didn’t come by five, Fantine began to sing what lulled Cosette to sleep. A servant informed the Sister that Madeliene went out that morning, Fantine demanded to know why he won't come. The Sister wouldn’t lie to her (her whole thing is not lying) and just said he had gone away and Fantine believes he had gone for Cosette.

Fantine laid back down and told the Sister of her daughter, she’s seven now so pretty and has beautiful hands. (this is called irony since we know how horrible Cosette looks but Fantine doesn’t) She believed she would see her again soon and he’ll be here with her tomorrow. When the doctor came at eight, Fantine was thought to be asleep but she wasn’t and asked if her daughter could sleep beside her. The doctor explained to the Sister that Madeliene will be gone for days, best not to give bad news to Fantine. She seemed to be doing better and he believed if Madeliene came back with the child tomorrow the great joy may cure her. (I’m not sure about anyone else but in my family if someone is really sick to the point of their deathbed and then appear to get better they’re half way to heaven about to die)

NEXT

0 notes

Photo

After reading this you might be asking yourself, who is this hater who seems to willfully misunderstand the plot? Well his name is Auguste Vitu (above left) and it all began to make sense to me when I found out that he was a journalist supported by Napoleon III (above right). As you can see he even adopted his benefactor’s hair style. Yikes. No wonder he didn’t like Les Mis.

Anyways, can anyone find me other early examples of what basically amount to fanfiction of LM where the author writes what they think ought to have happened? Sure towards the end he’s just listing things he doesn’t like but also his re-write fairly detailed, even if it is only done out of spite.

Source: Le Figaro, 24 March 1878 (2/3)

Why does Jean Valjean, who has in his pocket his savings of 109 francs an 15 sous from his time as a convict and who has in his bag the bishop’s silver, steal 40 sous from the Savoyard child? And why does he only steal 40 sous, when the child has clean money in his dirty hands? Inexplicable action that goes unexplained. Lets assume that he is punished by forced labor in perpetuity due to the highway robbery and recidivism, this condemnation would be pronounced with Jean Valjean in absentia.

That being said, let us ask ourselves what would happen in a real city, in the case where M. Madeleine found himself obligated, in order to save an innocent man, to reveal his forgotten past to everyone.

Don’t forget that he is a big business man, a millionaire, mayor of the city by decree of the King, and that he cannot be arrested or prosecuted in any jurisdiction without the permission of the Council of State, having been dismissed by royal ordnance. Well! Mister Mayor of Montreuil wouldn’t waste a night and a day running to Arras. He would go, without leaving the city, to the royal prosecutor with whom he conifers daily by duty and, in the privacy of the cabinet, he would explain the situation. The royal prosecutor, following the hierarchy, would warn the general prosecutor who would request the dismissal of the case against Champmathieu until another session. In the meantime, all would be explained. Jean Valjean, or rather M. Madeleine, would ask that his sentence be revoked, making a great effort to show how he tried hard to find the little Savoyard to make up for the consequences of an act that was more thoughtless than premeditated. And because it is public knowledge that M. Madeleine is an honest man who for 8 years has rendered great services to the country and who endeavored by countless means to redeem the faults of his past life, the attorney general, informed by the public prosecutor’s office, would present to the minister’s counsel the following missive:

“Let's avoid the terrible scandal that would arise from the appearance in the criminal court of a mayor appointed by the King; let's not give the liberal press the satisfaction of proving that we choose our mayors from the prisons; M. Madeleine will resign, and the King will pardon fully and entirely the convict Jean Valjean, who will return to the shadows and the silence never to come out of it.”

That is what should have happened because M. Madeleine, as they presented him to us, had become too serious a businessman and too experienced a magistrate to think, even for a moment, of acting otherwise.

There are lots of other extravagances in the play. For example, Fantine descended down to the lowest echelon of vice. Why? Because she was fired from M. Madeleine’s factory because of her status as a single mother. Is that realistic? Is that possible? Would M. Madeleine have lost all sense of humanity? He himself a wretch, would he treat other wretches, less guilty than he, with such harshness? The author of the drama foresaw this objection and had one of the characters say for him “M. Madeleine knowns knowing of what happens in the women’s factor. It’s not him who is firing you, it’s the rules.” But those internal rules of the factory, who came up with them if not M. Madeleine himself?

And what is the significance of the scene where Jean Valjean lets himself be extorted for 15 hundred francs by Thénardier in order to buy the right to take Cosette, when in his pocket he has a letter written by Fantine that authorizes them to give the child to the man who will come to take her?

All of that is outside the realms not only of truth but also any likelihood or common sense.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jean Valjean is my fav character ever , he was always kind, patient, compassionate, utterly selfless, he’s the one who is always there for everyone around him and understanding everyone, trying hard to atone for his sins , He helped a lot of ppl in Montreuil-sur-mer, he was a wonderful man for Fantine and a true father for Cosette, and even he was patient with Javert and eventually saved him , He went to the rampart to save Marius but he also helped everyone there ! , He was brave and gave up his position as mayor to save Champmathieu, Of course he has some faults that make him a human being, as he is not an angel after all, and this is what makes me love him as he does his harshest things to be good with ppl and his daughter , What a wonderful character, He makes me a better person and I dont think i’ll ever stop saying how much i love him and how important he is to me he deserves so much love , I really felt broken when he went away but he's still alive in my heart and soul forever.

Maybe for some ppl i seem ridiculous coz he's just a fictional character but i feel so connected with him.

[ Unfortunately, my language doesn't help me explain my feelings, but I tried to talk about a little bit of what I'm feeling sorry if there are some mistakes. ]

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brickclub 1.2.3 ‘The heroism of passive obedience’

I... oof, it’s all too iconic, and I’m choking a bit on how to talk about a scene that’s just this Big.

I’m fascinated by Valjean’s voice here. He sounds like Hugo’s misérables in a way that he won’t later: he sounds like Éponine, he sounds like Champmathieu. He rambles, he blurts things out because he’s bursting to say them, he’s not tracking how it’s odd to explain to a priest what a bishop is--all the niceties and decorum of bourgeois speech aren’t something he’s learned yet.

And he’s just so honest. He’s actually incredibly sweet. I mentioned a couple of chapters ago how he felt humiliation stronger than he felt hunger or fatigue, and he says as much here: that he was hungry when he came in, but because of the bishop’s respect, he can’t feel it. He wants respect and belonging so much, and he wants them on genuine terms. He seems absolutely terrified of being welcomed into a house by someone who doesn’t know what he is.

..And he never gets over that, does he? Years from now, when Cosette tries to welcome him into her home, he throws himself out because no one else will. Is it fear of being discovered? Is it an unwillingness to be taken for what he’s not? He’ll tell Marius about the weight of the lie on his conscience and the relief of relinquishing it. It feels like this far less sophisticated Valjean wants exactly the same thing.

There’s so much warmth in this character, before anything has changed about him, before we know anything about him besides what he’s blurted out. Valjean at his apparent moral worst is more desperate for belonging and honest respect than he is for food, though he’s starving.

And he never, ever realizes this.

I don’t think he ever understands that the bishop didn’t superimpose goodness onto a canvas of terrible evil. In future he’ll think of himself as someone who needs to atone every minute of every day in order to keep from backsliding, but the bishop only changed how he views his role in the world and the sufferings of others. Valjean’s instincts at his worst and his instincts at his best aren’t that different. Valjean’s soul, bought and unbought, is the same soul.

What does it mean that pre-transformation Valjean is this sweet? Valjean isn’t a hardened criminal, he’s someone vulnerable and on the cusp of becoming something he’s never been before--because of the choices the prison system left to him, it was very likely going to become hardened criminal, but he actually never got that far.

When similar generosity is offered to more hardened criminals (Montparnasse, Thenardier) it doesn’t take.

There’s an idea here that the goodness in people is there all along, if only society would stop crushing it out of them. But STILL:

This purports to be a book about radical change, so what does it mean that Valjean didn’t change as radically as he thinks he did?

85 notes

·

View notes

Photo

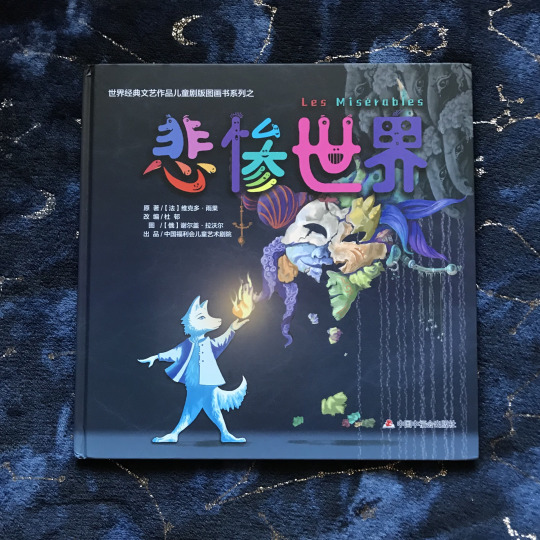

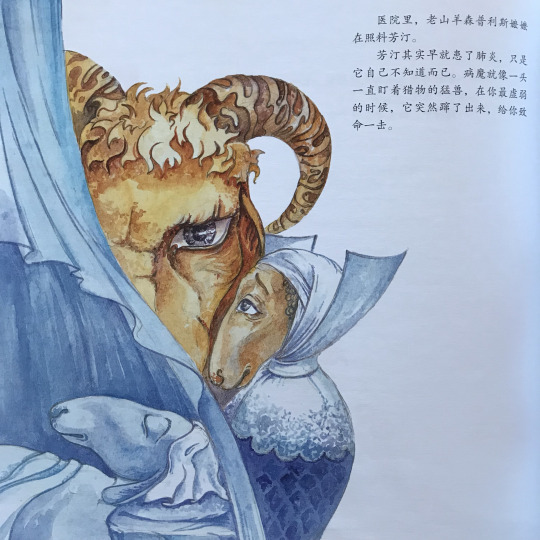

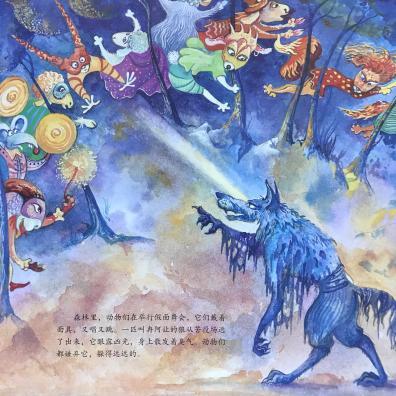

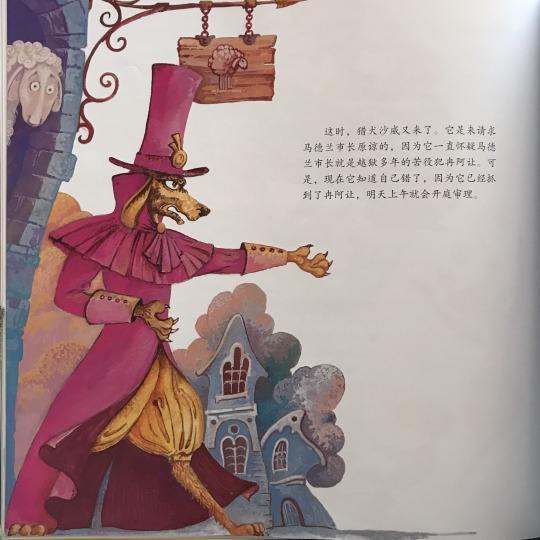

Hey! So! I just got what’s probably one of my favourite weird niche pieces of les mis merch and it’s this children’s picture book with all the characters as Symbolically Relevant Anthropomorphic Animals!!

The book is the novelisation of a Chinese Les Mis stage play and it’s illustrated by a Russian man named Sergey Laver (who also did the set design for the play! Just look at his art it’s so beautiful I love it ;w;) The play was made by a children’s theatre company who also previously preformed adaptations of titanic and Notre Dame de Paris!

The story has been adapted in a way that’s definitely... interesting?? Wolf Valjean escapes from prison where he’s forced to do hard labour, but all the other animals are scared of him and none will help him. Goose Myriel takes him in, Valjean steals his silverware, he gets caught by dog police officers and Myriel covers for him. Many years later, ewe Fantine and her lamb daugher Cosette are on their way to the sheep town of m-sur-m, when they meet the fox Thenardiers. The Thenardiers take in Cosette while Fantine finds work in a factory, but when the other ewes find out she has a child they chase her out onto the streets. As she walks away from the factory she’s hit by a cart and trapped under it. The mayor of the town, a large strong ram, comes to her rescue but this arouses the suspicions of dog police inspector Javert. Desperate to provide for her daughter, Fantine sells her wool coat. She’s bullied and harassed by the locals but when she tries to fight back she’s arrested by Javert. Madeleine arrives to take her to the hospital, but she’s already too sick from not having her warm wool coat in winter that she dies soon after. Javert confesses to Madeleine that he had been suspicious of him but tells him that the real Valjean has been found and is being put on trial. Since her mother is now unable to look after her, Madeleine goes to rescue Cosette from the Thenardiers. He then takes her to the bishop and leaves her on his doorstep with the candlesticks in her arms. Meanwhile at wolf Champmathieu’s trial, Javert has brought jackal Brevet and donkey Cochepaille in to verify his identity. However, at the last minute Madeleine bursts in and tears off his sheepskin, revealing wolf Valjean underneath. Valjean states that he will not let an innocent man preform such hard labour in his name... and then he’s taken back to prison the end!

I mean it’s an effective way to dramatically cut down the story and number of characters I guess? :’3 The company actually talk about how the changes they made were to portray a positive and simple message that children could understand which like,,, it sure is a simpler storyline I’ll give you that!!

“The children's drama "Les Miserables" actually only draws a quarter of the original content, which is different from the original. The first "Titanic" of the "Classic Literary Works Children's Series" talks about "responsibility and responsibility", the second "Notre Dame de Paris" talks about "justice and evil", this children's drama "Les Miserables" speaks of "honesty and openness." [x] (sorry for the bad google translate but you can mostly tell what they’re saying uwu’’)

I’d definitely recommend checking out their website (linked above!) if you haven’t already seen the costumes and stage design for the play because they’re really beautiful! <3 Hshdfsdf I’m just so happy that I have a physical copy of the book for myself now because it’s exactly my kind of thing lol uwu I’d be happy to upload photos of all the art in the book with translations for the text if that’s something people are interested at all? It’d just be run through google translate with a couple of edits from me to make the sentences more coherent so it wouldn’t be the most accurate translation but it’d get the gist of it across uwu’’

#les mis#les miserables#javert#jean valjean#fantine#cosette#eponine#thenardier#bishop myriel#monsters of our making#building a brick wall#men like queue can never change

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Top 10 favourite characters from any fandom

I was tagged by @limalepakko , thank you! Since I have recently listed male characters here (or you know, in August, but we all know time hasn't been a thing for many moons), I took the liberty to list characters in general this time. I also went with which characters feel right at the moment, so does not show all my favourites. I also try to keep these short. (edit: okay so these are not remotely short, I will post a list first and have the explanations be under the cut, read if you want to hear my ramblings c': )

1. Fantine, Les Misérables

2. Javert / Jean Valjean, Les Misérables (yes i am cheating)

3. Carrie "Big Boo" Black, Orange Is the New Black

4. Jane Marple, Agatha Christie's Marple

5. Aunt Lydia, The Handmaid's Tale

6. Bridget Jones, Bridget Jones books & movies

7. Rock Lee, Naruto

8. Sarah O'Brien, Downton Abbey

9. Marilla Cuthbert, Anne of Green Gables / Anne with an E

10. Sister Monica Joan, Call the Midwife

*

1. Fantine, Les Misérables

I love Fantine with all my heart. I remember reading Les Mis for the first time and her story sending chills down my spine. Her character development makes me so sad, from a girl who falls hard and fast and won't deny anything from her lover, to a woman who is so beaten down by society that she can't do anything but laugh at her fate. But I love how she doesn't lose her pride or her fighting spirit and how she still has the guts to spit in Valjean's face when she sees him after being arrested. And I love how all she does is for her daughter and how despite selling "the gold on her head and the pearls in her mouth" she is content, because all that matters to her is that Cosette will live.

*

2. Javert & Jean Valjean, Les Misérables

I was really trying to limit this list to one character per fandom, but alas, I am but a weak little person. Thus, I am cheating already. The thing is that when it comes to Les Mis characters, Fantine, Javert and Valjean are the eternal top 3 for me, but I'm never quite able to say who I love the most. Last time I picked Javert for the male character meme because I love the symbolism and critique of society his character embodies, but let it be known that Jean Valjean is the best character in all of literature and I will fight you on this. The original soft on crime icon (aside from Jesus Christ but they're the same and you know it). Valjean's character journey is such a complicated one from an ordinary man (no worse than any man) to a person, who had been shaped by society and criminal justice system to be a very dangerous man, to someone you could compare to a saint if you wanted to... To an ordinary man, who would do anything for his daughter. He has so many character-defining moments, the biggest ones being in my opinion the trial of Champmathieu and letting Javert go instead of killing him. I just love Jean Valjean so much and could speak about him for hours.

*

3. Carrie "Big Boo" Black, Orange Is the New Black

Hopping away from the Les Mis hole and into a OITNB hole. I was debating on whether I'd put Boo or Pennsatucky on this list since I love them both so much, but I've been feeling so much love for my angry butch king that it had to be her. First of all, I'm just so happy to see butch lesbian representation where the butch identity is not just a joke. I know OITNB sometimes uses Boo questionably, but in general she is a nuanced character and one of the most interesting ones in the series in my opinion. I'm so sad they forgot all about her on the last seasons. I love everything about her, how she has trouble with feelings besides anger and often deflects serious stuff through humor, how fiercely protective she is of those she loves (boosatucky otp forever fucking fight me), how proud she is of her butch identity ("i refuse to be invisible")... Also, not to express attraction, but... Mama I'm in love with a criminal. And not to be a slut for how characters view religion/spirituality/God, but the relieved smile she has in one of her flashbacks when she says "there's no God... there's nothing", like you can't just do stuff like that and expect me not to love the character to bits.

*

4. Jane Marple, Agatha Christie's Marple

Last time I listed Poirot and was a bit frustrated I couldn't list Marple, but now it's time to right that wrong! I love this little old lady so much. I love Agatha Christie so much for just going "you know who is the person who knows everything that's going on in a community, and thus would make the perfect detective for a detective story? the nosy old woman". As she is introduced in The Murder at the Vicarage: "Miss Marple is a white-haired old lady with a gentle, appealing manner — Miss Weatherby is a mixture of vinegar and gush. Of the two Miss Marple is much more dangerous." She is so likable and witty, you can't help but love her. My favourite portrayal of her is by Geraldine McEwan, she looks so gentle but has such a sharp gaze. I would spill all my secrets to her any day. I also am compelled to tell you that when I was a child we had a costume party at my school and I dressed up as Marple and learned some old lady things in English (it was before third grade so I didn't know much English back then) just for the occasion (such as "thank you, my dear", "what a lovely necklace you are wearing" or "there has been a murder"). Teacher might have thought me rather morbid but I remember that day being quite good.

*

5. Aunt Lydia, The Handmaid's Tale

The Handmaid's Tale is such a great series and a book and Aunt Lydia is such a great character. The way she's capable of being absolutely cruel and vicious, but how she is also protective and caring in her own way. One of my favourite scenes in this series is when Serena Joy (my other favourite, can you tell) tells Lydia to "remove the damaged ones" from a line of handmaids and Lydia tries to argue with her. Sure, she is responsible for some of the punishments these women are now "damaged" by, but she truly believes those punishments were for a greater good and now the handmaids deserve their place with the others as much as anyone else. It is chilling and the character is such a dark shade of morally gray, but I can't get enough of it. The actress who plays her, Ann Dowd, has so interesting thoughts about her, like here. I just love this character so much I could scream.

*

6. Bridget Jones, Bridget Jones books & movies

I'm mostly talking about the movies here because Renée Zellweger's performance is iconic. Plus the movies are what made me love this character first. But I'll give it to the books, they're one of the few books I've laughed out loud while reading. Anyway, how do you even begin explaining the love I have for Bridget Jones... I love how she is a character so many people can relate but who would be a comic relief side character in some other story. Yes, yes, it is really bad that she is constantly described as fat when she really is not, but when I was growing up she gave me hope that people who are viewed as fat and/or unattractive by other people can be admired and appreciated, and they don't have to be super talented at everything and highly intelligent and some kind of a super smooth social butterfly to "make up" for what they "lack". And also that they can have standards (i once dodged a bullet by rejecting someone by pretty much subconsciously quoting Bridget Jones so..). I also love how the comedic tone of everything does not dismiss Bridget's feelings. For example in some other movie we maybe would concentrate on how "stupid" Bridget was to trust that Daniel was in love with her, but in Bridget Jones we concentrate on how Bridget was hurt by Daniel cheating on her, how he is the one who did wrong. Idk I just love Bridget Jones so very much can you tell.

*

7. Rock Lee, Naruto

Aka the boy who would have kicked Madara in the balls if Kishimoto had any sense of drama and good storytelling. I think I robbed Lee by not putting him on the fav male characters list. You know that post that goes like "gays be like 'these are my comfort characters', 1 literal ray of sunshine, 2 war criminal" etc? This child is the sunshine. I've been reading and watching Naruto again ( @hapanmaitogai is my sideblog for that nonsense) and I'm so ready to adopt Lee and/or Gai. Rock Lee is just such an earnest character, he has a goal he will give anything to achieve and he's the one true underdog in this manga. I love how he's so kind and polite (it's not so clear in English but in the Finnish translation he speaks as formally as he does in Japanese, he uses singular polite "you", calls Sakura "Sakura-neiti" = "Miss Sakura" etc... i love one polite boy). Also, he has the best fights in the series. Like Lee vs Gaara is a Classic, but we simply can't forget that time Lee absolutely crushed Sasuke in just a few minutes, or that time he politely asked Kimimaro not to kill him while he drinks his medicine. The best boy. I love that boy so much.

*

8. Sarah O'Brien, Downton Abbey

Last time it was Thomas' turn, so now I must talk about the snakiest snake, the queen of weaponized handmaidenry, Miss O'Brien. She is such a great character especially in the first two seasons (I obviously love her on season three as well but Julian Fellowes really tried to make it hard by not explaining her actions at all, didn't he. Well, luckily I am ready to stuff the gaps with my headcanons). She has some of the best comebacks in the series and brings some needed realism in some conversations. I also love how she uses her position as a lady's maid for her advantage and how she is proud of her profession despite being highly aware of the power structures in the Abbey. And then there is the soap. That is such a good character moment, because for a character who always plans ahead, who is ruthless and cunning and intelligent... I don't think O'Brien thought about the soap thing at all before she left the room ("Sarah O'Brien, this is not who you are" hit me like a train). Just once she did something with nothing but anger motivating her and that became one of the defining moments of her character. And one of the defining things of the future relationship between her and Cora. That's why I find the Sarah/Cora ship so interesting, because there will always be the undercurrent of bitter regret. Also Sarah O'Brien and Thomas Barrow are the greatest brotp and Fellowes was a coward for driving the smoking scheming gay best friends apart, and

*

9. Marilla Cuthbert, Anne of Green Gables / Anne with an E

I'm not saying L.M. Montgomery is entirely responsible for me having a fondness for strict, older women who first act unkind but have a heart of gold, but she most certainly did not help. Between characters like Marilla Cuthbert and Elizabeth Murray, how can you not fall in love with the type? It's been a while since I read the Anne series, but I really love how Marilla's character has been adapted into the Anne with an E tv series. Geraldine James looks like she was born to play her, she has me in tears so often. She has the ability to portray someone like Marilla, who is a very hard and stern person but feels deeply for her loved ones. I was watching the episode that dealt with Matthew's heart attack and Marilla berating her brother while hugging herself like she was trying so hard to hold herself together absolutely destroyed my heart.

*

10. Sister Monica Joan, Call the Midwife

It was a tough choice between her and Sister Evangelina. I just love these nuns very much. Sister Monica Joan is such a lovable and wise character. She is so knowledgeable of many subjects, from the Bible to astrology, and I feel like her unspecified memory problems and confusion are handled very tastefully. I also love how she's such an important part of her community despite not working as a midwife anymore. She is such a kind woman and gets visibly upset when others are treated poorly. And how could I not mention her saying "I do not believe in weeds. A weed is simply a flower that someone decides is in the wrong place", like... I love her so so much.

*

I won't tag anyone, but if you read this and you want to do this, consider yourself tagged and you're no allowed to mark me as the one who tagged you!

#this list was fun to make#sorry for rambling#i just really like talking about my favourite characters#do you have a minute to talk about eleven losers#or well.. like four losers?#hm. let's tag#fantine#jean valjean#javert#boo#aunt lydia#bridget jones#rock lee#sarah o'brien#miss marple#those are the ones i have character tags for but let's tag also#ctm#anne with an e#anne of green gables#phuh#many characters#much love

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brickclub Retrobricking: 1.7.3, “A Tempest in a Skull” and 1.7.4, “Forms That Suffering Takes in Sleep”

Between con planning and fic writing, I fell way off the brickclub wagon. Hoping to get back on it day-to-day with Waterloo, starting next week; meanwhile, this is the start of an extremely scattershot writeup of my margin notes from the last 70-odd pages, organized more thematically than anything else.

(All quotes from Donougher, except for a bunch of the chapter titles because the FMA ones are just engraved in my brain. Also, can I say how excited I am to look ahead and see just how many notes Donougher has for Waterloo? SO MANY NOTES. SO EXCITE. Also excited for CONVENT NOTES.)

Firstly—the entire sequence of the Tempest in a Skull, the trip to Arras, and the trial is just so *good*. Every time through I forget just how good, but it’s some of the most suspenseful writing I’ve ever read, even knowing what’s going to happen next—almost by heart at this point.

Ecce Homo: The chapter starts out by finally telling us, “The reader has no doubt guessed that Monsieur Madeleine is none other than Jean Valjean.” And then, having given him that name, it doesn’t use it for him again until he uses it himself, in the courtroom. For the next 50 pages, he’s just going to be called “the man.” (Or occasionally “the traveller,” which comes to the same thing.) And partly this is a nice piece of identity porn, withholding a name from the protagonist until he decides who he is going to be. But it’s also underscoring from the start the decision he’s going to make—to be *The* Man, Behold The Man, Voila Jean.

He’ll finally shed his name on his tombstone, in another parallel to Napoleon, whose monument has no name because of a protocol disagreement over whether to use his last name. Valjean tries to shed it here—to just be *a* man—and he can’t; he can still be Madeleine, but the moment he drops that specific alias, anonymity just makes him Voila Jean again.

It feels appropriate to that—as well as very believable as a character note—that he keeps making his preparations to go to Arras, to drop his life as Madeleine, automatically, in a sort of fugue state. When he does stop and think, we get the recurring insistence to himself that Champmathieu was probably guilty, that he probably deserved to go to the galleys for something. It’s awful, though believable.

—In the opening paragraphs, there are two Dante references which mostly don’t seem to be followed up on, but which do make me look twice at his remembering, in the courtroom, that his previous trial was 27 years ago. Valjean is 54; his first descent into hell came exactly in the middle of his life to that point, which does call back to Dante’s *media vita.*

—We also get an aside about how noble it would have been had Valjean not hesitated in walking “toward that yawning precipice at the bottom of which lay heaven.” Hugo really, really likes that inverted abyss image; it keeps coming up over and over.

And wow Hugo’s just stopped being subtle at all about the Christ thing. (Okay, the brief mention of his burning the credit notes for money owed to him by small shopkeepers—literally forgiving his debtors—is a little subtle.) But early on, we get the explicit comparison to “another condemned man 2000 years ago,” on the off chance that we hadn’t picked it up yet, and the chapter ends with a longer and quite lovely Gethsemane comparison that also picks up on that inverted abyss image:

“Thus did this poor soul struggle in its anguish. Eighteen hundred years before this ill-fated man, the mysterious being in whom are concentrated all the saintliness and all the sufferings of humanity had also refused for a long time the terrible chalice, streaming with darkness and brimming with shadows, that appeared to him in the star-filled depths, while the olive trees shook in the fierce blast of the infinite.”

Petit-Gervais: The shade of Petit-Gervais is all over these chapters—reasonably so, since that is the second offense that has been on Valjean’s record all this time, and that would still send him to the galleys or the guillotine without even needing to consider, say, all the fraud he’s been doing as a matter of course to maintain his identity as Madeleine. (Including the passport he used TO VOTE IN THE ELECTIONS. Because Madeleine is that wealthy.)

And that made me stop and think about how weird it seems, honestly, that an itinerant child chimney sweep would have reported the theft—would have trusted authorities enough not just to think it was worth reporting, but to trust that he wouldn’t draw any hostility, or risk arrest for vagrancy or be accused of any local petty crimes.

And then I wondered whether he reported it because he knew you could trust the authorities in Digne to take it seriously, because the bishop would hear about it. And then I had a sad.

The Dream: The beginning of the dream in 1.7.4 recalls the Petit-Gervais incident, of course, with its empty dust-colored plain and lone rider. But I was also reminded of it by the brief waking dream in 1.7.3: “He felt as if he had just woken from some sort of dream and had found himself sliding down a slope in the middle of the night, standing, shivering, backing away in vain, on the very brink of an abyss. He distinctly perceived in the gloom a man he did not know, a stranger that destiny mistook for him and was pushing into the chasm in his place.” It feels like the missing piece that ties all those abysses and inverted abysses into the P-G scene, with its terrible open space under the sky.

The brother has them take a sunken road, where nothing grows and everything is the color of earth. It’s clearly the grave, and now we know to be afraid when we first read about the sunken road in Waterloo.

Beyond that—I just always love how realistically weird this dream is. It feels like an actual dream—in some places transparent, in some just random (“Why Romainville?”), but mostly very clearly significant in ways that don’t obviously map onto any single reading. Why does Valjean keep walking into empty houses, rooms, streets, and only finding a man in the second one he enters? I would say it’s because the first place is Madeleine, where he is now, and he doesn’t have a self there, but honestly hell if I know. It’s a dream.

Fursona Watch: Valjean himself thinks of Javert as a hunting-dog, possibly for the first time. (Also, I really want to come back to the voice, of God or conscience, that tells Valjean to burn the candlesticks when we get to Derailed; their diction is so similar.)

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of the most heartbreaking moments in Les Mis is when, after travelling through the sewers until he’s nearly dead, Valjean reaches the end only to discover the sewer’s outlet is locked -- using the same kind of locks they use in prisons-- and he can’t get out. As he collapses we’re told that:

“He had only succeeded in escaping into a prison.“

I get so emotional over how that one line, that one moment, summarizes his entire story.

Valjean really does just.... constantly escape from one prison into another prison, over and over and over again.

Valjean’s years in Toulon were made up of desperate escape attempts where his hours of “freedom” are described as:

He wandered for two days in the fields at liberty, if being at liberty is to be hunted, to turn the head every instant, to quake at the slightest noise, to be afraid of everything,—of a smoking roof, of a passing man, of a barking dog, of a galloping horse, of a striking clock, of the day because one can see, of the night because one cannot see, of the highway, of the path, of a bush, of sleep.

And are these escape attempts all followed by years added to his prison sentence.

After he was freed from Toulon he suffered “the imprisonment of his name,” being turned away and punished and starved because of his background. After he robbed Petit Gervais and became a wanted man again, he returned to that state of paranoia mentioned during his Toulon escapes: aware of how tenuous his “freedom” was and paranoid it would be taken away. He lived in that paranoia even when he was happy in M-sur-M--- until the Champmathieu trial happened, his world collapsed around him just as he always feared it would, and he was imprisoned again.

Then he escapes THAT prison (twice), and picks up Cosette while he’s actively on the run from the police. He climbs over the wall of a convent to escape being imprisoned by Javert, and then it turns out--the convent is yet another prison!

(The convent) was the second place of captivity which he had seen. In his youth, in what had been for him the beginning of his life, and later on, quite recently again, he had beheld another,—a frightful place, a terrible place, whose severities had always appeared to him the iniquity of justice, and the crime of the law. Now, after the galleys, he saw the cloister; and when he meditated how he had formed a part of the galleys, and that he now, so to speak, was a spectator of the cloister, he confronted the two in his own mind with anxiety.

Even when Valjean is living with Cosette in Paris the threat of prison is always hanging over his head. I mentioned before how one thing that struck me while rereading the Brick was how hyper-militarized the country is, how the police/the National Guard/prison are basically omnipresent.

Valjean tries to take Cosette on a peaceful walk to see the sunrise and they encounter a chain gang. Valjean tries to take Cosette on a peaceful walk in the Luxembourg gardens and he’s followed home by a young man who begins interrogating his porter about his past, making Valjean assume he’s a police spy. He’s captured by Thenardier and can’t call for help because he’s afraid the police will come--- when the police accidentally “save” him he barely escapes being arrested. Valjean and Cosette live in the Rue Plumet right next to barracks of soldiers. Cosette falls in love with a boy and then, right after Valjean discovers this secret romance, he discovers the boy is in danger of being killed by the National Guard.

He escapes the barricade by climbing into the sewer. There are police hunting for insurgents in the sewers too, and he escapes the police. He journeys through the sewers for hours and hours and hours, until he’s nearly dead, and when he reaches the end!

The tunnel ended like the interior of a funnel; a faulty construction, imitated from the wickets of penitentiaries, logical in a prison, illogical in a sewer (....) The door was plainly double-locked. It was one of those prison locks which old Paris was so fond of lavishing.

There’s something so horrible, eternal, and cyclical about it.

Valjean is talented at escaping! He’s literally an escape artist. He’s inhumanly strong, ridiculously cunning, highly skilled and quick-thinking enough to make a thousand daring escapes in a thousand impossible ways—

Its just that every time he does, the place he escapes to is always another prison. And he has to find a way to escape, again.

Valjean compares himself to Sisyphus and Prometheus at different points, and...agh, yes. It’s like he’s stuck in a time loop, suffering this repeated pointless useless punishment again and again, aging and growing more tired, for all eternity.

The moment when he collapses at the grate of the sewer, unable to continue, having completely given up.... I’ve gone back and forth on how much the barricade drama affects Valjean, but after rereading it I really think it DOES make a big impact on him. I think it’s the turning point where finally he becomes too tired to continue, where he stops finding the strength to continue pushing the boulder up a hill.

I also think this is why Javert letting Valjean go is so impactful to me.

With the help of Thenardier, Valjean he escapes the sewer-- only to immediately encounter Javert. Once again, he’s escaped one prison only to fall into another prison. He’s accepted it. He’s resigned to it. He promises Javert to come quietly if Javert helps him take Marius home, and he fully intends to honor that promise.

But like! Every previous time Valjean went to prison, he was determined to escape. He attempts to escape repeatedly from Toulon; and when he’s re-arrested in M-Sur-M he goes to prison with the full intention of escaping at the first opportunity. (And he does! Twice!)

But here we see Valjean surrender himself to prison without any intentions of escaping. He surrenders himself to Javert’s custody with no plans to free himself. He considers everything “over for him,” in a way that’s compared to suicide.

And that’s when there’s a “concussion in the absolute”-- when Javert Finally (FINALLY) realizes the laws he’s enforcing are wrong, refuses to do his job, and refuses to arrest Valjean.

The moment where Javert lets Valjean go free is a brief unexpected flash of hope. After all the horrors National Guard and the sewers you believe, for a moment, that the cycle can be broken! That maybe there’s still a chance!

After Valjean’s spirit was crushed and he finally resigned himself to prison-- he finally gave up on escaping-- he was given one miraculous last chance at freedom.

And there’s a brief moment of hope that maybe this time he will actually get it!

But he doesn’t; his self-loathing and Marius’s bigotry end up imprisoning him again. Valjean begins to see death as the only way he can escape:

“The dead are not subjected to surveillance. They are supposed to rot in peace. Death is the same thing as pardon (....) would that I could die!”

Which echoes what Javert thinks before his suicide:

Legally, death puts an end to pursuit.

And it’s so frustrating because none of this needed to happen. Valjean should never have been arrested in the first place; and the parallels between his story and the over-incarceration of people today are heartbreaking. Valjean’s punishment was never just, it was never right, it was never reasonable, and yet it just kept going endlessly until his death.

It really makes you want to grab the book and create a better ending, and to get angry at the pointless cruelty and injustice of the world around you; which I guess is the entire point.

#les mis#jean valjean#ALSO i didn't know how to fit this into the post#but everything about the fontis scene#where Valjean is sinking into the mud beneath the sewer#and Hugo describes how the only thing worse than a slow painful death#is a slow painful death that takes place somewhere 'shameful' like a sewer#(and- though this is implied rather than said- like the galleys)#and how it's...symbolic......;-;#but YEE#;_:#why does victor hugo insist on torturing his poor oc like this#anyway the point is: fix it fic#also donating to funds working towards prison abolition

332 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brick Club 1.5.6 “Father Fauchelevent”

We’re introduced to two “enemies” of Valjean back to back. First Javert, and now Fauchelevent, who was jealous and distrustful of Valjean’s successes. Fauchelevent’s mind is changed by Valjean’s act of rescuing and helping him. Similarly, Javert does not start to change his mind regarding Valjean until Valjean spares him as well.

My favorite thing about Fauchelevent (aside from how weird he is later at the convent) is his representation of redemption cycles. He disliked Valjean, and was “punished” for that judgement by going bankrupt; Valjean saves him despite the (likely known) negative efforts of Fauchelevent to undermine him, purchases his cart & horse, and arranges for him to have a job that is possible with his broken knee; Valjean then forgets about Fauchelevent entirely; Fauchelevent reappears later with a vastly different view of Valjean and ends up essentially saving him from under the proverbial cart of Javert.