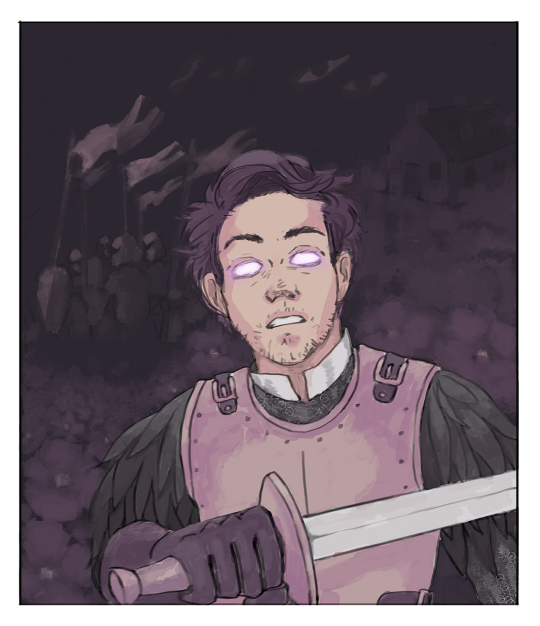

#adaryc cendamyr

Text

the watchers at the battle of yenwood field.

#remembered u can get the iron flail to help u <3 babygirl what are we <3#pillars of eternity#oc: allara leonis#adaryc cendamyr#my art

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

blank_stare.png

blank_stare(1).png

39 notes

·

View notes

Note

If you want to do more voice line compilations, how about one with combat voice lines?

Indeed I do! Since you didn't specify character or situation I decided to be a bit creative. I did limit the ones that are just funny noises but those last two made me laugh too hard to not take them. xD Also turns out Maneha has a whole set of very funny reactions like this one, I might do that one seperately some time.

#pillars of eternity#audio#voice lines#edér teylecg#maneha#hiravias#pallegina mes rèi#devil of caroc#grieving mother#durance#concelhaut#adaryc cendamyr#did have to take two deadfire portraits for this#it continues to shock me that adaryc doesn't have in the white march#did my boy dirty#eventually i'll probably get to deadfire but I don't have that one installed currently so later

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Adaryc as Sidekick mod

The mod is finally finished. Well, version 1.0.0 is >:3

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recounting the halcyon times, watcher?

#quinttyz draws#yea caed nua before eothas decided to destroy it was really..peaceful..#bittersweet but still…peaceful#maybe in another life tempest and adaryc got together in the end 😟#i love torturing myself with thoughts of my watcher and the what could have beens..lol!!#midterms just finished!! tried coloring a piece that was originally just supposed to be a sketch haha#pillars of eternity#pillars of eternity fanart#adaryc cendamyr#adaryc cendamyr x watcher#pillars of eternity 2 deadfire#deadfire fanart#my watcher#oc: tempest withers#adaryc cendamyr fanart

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

to begin another end

When one of his oldest friends is killed during the events in the Whitemarch, Adaryc must travel back to the village where they grew up to bury his remains, and in the process is forced to confront the realities of loss, identity and his own complicated relationship with his roots and his faith.

Content Advisory: religious trauma, attempted suicide, references to self-harm

.....................................................................................................................

Those first days after they returned from the Whitemarch were a blur of exhaustion. They dug graves, conducted services, redistributed belongings, held collections, Adaryc wrote letters – too many letters – to families. And even in the midst of death, the living could not be forgotten, Marwyd needed medical supplies urgently, the duty roster needed to be reorganized to account for their casualties, supply lines needed to be reopened in the surrounding area, new jobs lined up. Adaryc didn’t sleep for two days and there still weren’t enough hours.

There wasn’t time to grieve. Not even for Devet. It still hadn’t sunk in that he was gone. Even as they prepared his body for transport, it wasn’t him, it was was simply another task that needed to be done.

Most of their dead were laid to rest in the hills outside Little Bend where the Iron Flail had a small, unofficial burial ground. But Adaryc had promised Devet, years ago, when they were both much younger, that he would take his body home to his family if it came to that.

Hel, scrape together some campfire ashes and tell them I got smoked by a spell-slinger. I don’t care. Just – promise me you’ll give them something to bury. Maybe that will give them some peace. Gods know I never did.

He remembered the crooked smile on his face when he’d said it.

Kae, one of his sergeants and closest friends, a mountain of a man who was closing in on fifty winters, volunteered to go with him. Only seemed right, he’d said. They’d grown up in the same parish, Adaryc and Devet and Kae. Enlisted together, fought together, made it home together. It had been the three of them there at the beginning, and there had never been a version of events where they were all still standing at the end, not in their line of work, but –

But. The words he couldn’t find ached like a hole in his chest.

They had been on the road since before sunrise, taking it in turns to pull the small two-wheeled cart which held Devet’s coffin. It was Adaryc’s shift; the late morning sun was warm on his shoulders, but the air still had the bite of winter in it. The cart bumped over the ruts left by the spring runoff, loudly jostling the coffin.

Adaryc caught himself grimacing at each impact. He had the absurd impulse to apologize, as though Devet’s corpse was still sensible to pain. His thoughts kept flashing back to the journey down from the mountains. To the wagon full of dead friends stacked like cordwood. To Devet huddled under blankets with the other wounded, with a ghost pale face and sweat beading on his brow, cracking jokes and stubbornly insisting that everything was fine.

Another banging rattle as the cart bumped over a rough patch of road and Adaryc’s jaw tightened. The weight was all wrong. It should have been heavier. There should have been more of him to bury.

He’d been getting better.

His thoughts kept tangling on that part.

It was a childish thought; he had seen enough of war to know that things did not happen because they were supposed to, because they were fair, or because they were deserved; they merely happened. It was one of life’s simplest cruelties.

But the knowledge did nothing to ease the guilt that twisted around his insides like garrotte wire: that he had walked away from Cayron’s Scar with naught but a broken arm and an aching head and Devet had–

He flinched away from the memory of those last hours.

The wagon shuddered over another rut, jarring him back to the present. Haligford was their destination, the small farming village in the South Dales where they had grown up. A two and a half day journey, he thought, if they kept a steady pace.

He shifted his grip on the harness strap. He hadn’t been — hadn’t been back — in almost fifteen years.

........................................................................................................................

There is a surreal quality to the months leading up to the war. News trickles out to the rural parishes in piecemeal, often conflicting reports – days, even weeks, after the events have occurred. They are insulated from what is happening in the wider world, but there is no comfort in that insulation, no safety. It is the difference between cover and concealment.

In a matter of months, the entire shape of the world has changed. Their god has taken a human avatar and chosen Readceras as his divine seat, he has expelled the Aedyran governor and declared the colony’s independence. And yet they still wake every morning to the same barren fields and empty bellies, the same crushing poverty, the same boot on their necks. Everything has changed and nothing has changed, and that dissonance hangs like a sword above their heads. The priests praise Eothas for his deliverance and no one dares ask what they are being delivered from.

When the blow finally comes, it is a perverse kind of relief. Waidwen’s gaze turns upon the Church, to root out corruption, or so it is said, but the watchword cried in every temple, is not ‘corruption’, but ‘heresy’. A small, but deft shift in rhetoric that removes the target from the backs of those in power and lays the blame and responsibility at the feet of the people.

The vorlas crop is rotting in the fields, and the trade agreements Readceras has depended upon so heavily for grain and other supplies are void now that they are no longer an Aedyran colony. People are starving. And their leaders, the voices they trust, tell them that all they have to do to make it stop is to rid themselves of the rot in their midst.

The purges hit the Waelites and Berathians first, the followers of Galawain and Ondra, the small sects dedicated to the other gods. Stories come from the cities of full scale proscriptions; in a village up river a family of Ondrites is burned alive in their house; in Haligford a crowd gathers outside the charcoal burner’s hut in the middle of the night, drags him into the street and chases him to the parish border. Adaryc remembers shouts in the the night and torchlight from the road. Wagons carrying frightened, hollow-eyed families pass through day after day fleeing south to the border.

And when they have driven out all those who follow other gods and their crops are still failing and their bellies still empty, they begin to look closer to home. To those at the edges of their communities, the outsiders, the misfits, anyone does not fit the shape that was prescribed for them.

Adaryc knows it is only a matter of time. His family’s status in the parish is liminal at best. He has no friends. He has always been viewed as ‘troubled’, but ever since the incident with the brewer’s boy the villagers look at him like a gul in their midst. Each night he wakes from nightmares of torches outside their windows. He knows that he is running out of time, and he knows that when they come for him, his father will not be spared; guilty by association.

But a holy crusade – no one could accuse him of faithlessness or heresy if he takes part in that, if he is willing to die for his god. Readcerans revere their martyrs. The dead and the unborn are far easier to love than the living. For all that he cares deeply for his country, that is one of the qualities that he hates the most.

He remembers sitting at the table with his father as the light fades. The hearth is cold; there is no food to cook and they can’t afford to waste fuel on warmth. As has been the case more and more since his brother Eadwyn’s death, talking only lead to arguments, and so they sit in silence, the only sounds the faint click and scrape of his father’s wooden needles.

Adaryc stares at his hands, balled into fists on the table before him. “Osbeorn said there was a messenger at the temple today,” be blurts out at last.

There is a tired sigh from his father. A stop at the temple meant an official proclamation.

“Waidwen is calling for volunteers for a divine crusade.”

The sound of the needles stop.

Adaryc takes a breath and pulls himself up a little straighter. “I’ve decided. I’m going to join.” His attempt at confidence comes out stilted and awkward and it is all he can do not to cringe as his adolescent voice cracks.

He waits, bracing himself. There is silence for several long moments, and then the soft clicking of the needes begins again.

“I’ll have to notify the reeve.” The words are slow, but wearily matter-of-fact. “They were counting on all hands for the second sowing. But I suppose it can’t be helped.”

Adaryc stares at him. Waiting for him to say something – anything – else, but he never even looks up from his work. He has been dreading this confrontation, expecting his father to be angry, to argue, to forbid it; so why does this concession feel so much worse?

He finds himself wishing that he would argue, that he would push back, call him an idiot, gods – ANY reaction at all would be better than this.

Adaryc opens his mouth to protest, to make him react. He is supposed to be furious, he is supposed to argue, to question him, or tell him what he ought to do instead, or – or —

All the words he wants to say tighten into a hard, painful lump in his throat.

He is supposed to care.

Adaryc does not wait for morning; he leaves in the middle of the night without a word to anyone.

...........................................................................................................................

“Hey–” Kae’s hand smacked against his shoulder, pulling him back go the present. He looked at Adaryc sidelong, a concerned scowl knotting his brow, “Come up for air once in a while, yeah?”

(When it was just the two of them, the sergeant tended to dispense with the formalities of rank. )

Adaryc cast him a look of rueful gratitude. “Sorry.”

They were approaching a crossroads, coming up from the south and turning west deeper into the South Dales. A post stood at the center, marking the distance in leagues to various waypoints. One of the names caught Adaryc’s eye.

“Ashwyck,” he said aloud.

Kae looked up as though he had heard the name of an old friend. After a pause he said, half joking, “Could always make a detour. See if that old tavern is still standing.”

It would have been fitting, but they both knew that they could ill afford the delay. The Flail couldn’t spare them any longer than was necessary, and Devet’s body had already begun to fester.

“He wanted to head west to the Bremen depot, you know?” Kae added suddenly, "When we enlisted, I mean. It being closer and all. At least until I pointed out our chances of getting ordered around by someone from home.”

“You’re right. That would be terrible,” Adaryc deadpanned.

Kae chuckled. “Present company excepted.”

“Do you remember that first night in Ashwyck?”

“I remember Dev going up to the bar to get us drinks and coming back with a prickly, half-starved teenager instead.”

The tips of Adaryc’s ears turned pink, recalling that first meeting. “I owe you an apology for that.”

Kae made a dismissive sound. “You were a bit riled up, is all. Devet used to joke that you were the only person he’d ever met with a stick up his ass and a chip on his shoulder at the same time.”

Adaryc snorted. “So, more or less the same as now?”

He was rewarded with a bark of laughter from Kae. “Nah. You don’t get your hackles up near as easy now. As long as we’re not dealing with slavers or landlords.”

“Or delegates from Stalwart,” Adaryc added bitterly.

Kae looked at him sharply. “You still whipping yourself over that?” He gave Adaryc’s shoulder a gentle swat.

“What was that place called?” Kae continued, his thoughts turning back to the tavern in Ashwyck, “The Ploughman’s – no, Pilgrim’s Rest. That’s what it was. I remember because they tossed us out when we couldn’t afford to keep drinking.” He shook his head, “Feels like a lifetime ago.”

.........................................................................................................................

“Look who I found!”

Devet’s voice booms over the clamor around them as he propels Adaryc towards a table at the back of the tavern where another man is seated.

“Another refugee!”

The choice of words sends alarm bells shrilling through him and Adaryc pulls away sharply.

“I’m no such thing! I came here to join the Divine Legion! To serve Eothas!”

The vehemence of his response startles a laugh from Devet who holds up his hands. “Take it easy, kid.”

“Take it easy?” Adaryc hurls the words back at him, the tension which has been building over the past weeks and months finally boiling over. “Tell that to the charcoal burner’s family! You think you can call me a heretic and just– “

“Hey!” The other man who has not spoken until now cuts Adaryc off sharply. “Sit down.”

Adaryc falters, blinking at him in surprise. The steady, even gaze holds his until he flinches away. And after a moment of sullen hesitation, he lowers himself onto the bench.

“Alright, first off –” There is a weary authority in his voice. “No one is calling anyone a heretic. This isn’t a fucking inquisition.

“Second – Bremen depot is a full day’s journey closer to Haligford. Only reason for you to be here in Ashwyck is if you’re trying to get away from something. Same as us.”

Adaryc’s hands ball into fists at his sides, eyes locked on the surface of the table. Shame at his outburst and at being caught out so easily colors his cheeks and fear twists in his stomach. This had been a mistake.

“Point is –” Devet interjects, dropping down next to Adaryc on the bench and giving him a playful nudge in the ribs. “You can relax. You’re among friends.”

Adaryc freezes in surprise at the words. No one has spoken to him like that since his brother died, and to his horror he finds himself on the verge of bursting into tears. His eyes sting and his vision blurs. He hugs his arms across his chest not daring to look up again, afraid that a kind look might shatter him.

“It’s Cendamyr, isn’t it?” asked the older of the two, who looked to be somewhere in his early thirties.

Adaryc instinctively straightened up at the use of his surname, the fact that the other man was addressing him as a peer and not a child. He nodded, sniffing and swiping at his eyes.

“I’m Kae. And this – well, guessing you already know Devet.”

Everyone knew the parish troublemaker.

Devet grinned, leaning forward in a mock bow. “My reputation precedes me.”

They talk for a little while before Devet slides a half-finished plate of food in front of Adaryc. A thin potage of beans and corn, heavily watered down to make it stretch farther, but it looks more substantial than anything he’s had in weeks.

Adaryc’s mouth waters and his head feels uncomfortably light – he hasn’t eaten since before he left home – but still he bristles, the offer touching the raw nerve of internalized shame that is his only inheritance from his father.

“I don’t need your handouts.”

Devet’s brows arch, his expression more amused than annoyed. “Is everything a fight with you?” he laughs, “Come on, you look like you’d blow away in a stiff breeze.”

Adary’s face flushes scarlet. “I – I thought –” he stammers miserably, wishing that he could sink straight through the floor. As indentured servants they had no income, subsisting on the meager rations provided by the estate. The temple’s charity always came with strings of guilt and shame attached and he had assumed this was no different. He is not used to people being kind for its own sake.

“I’m sorry.”

Devet waives off the apology. “Can’t have you fainting in front of the enlistment officer, can we? Besides,” he adds, “I meant what I said before. You’re among friends.”

.........................................................................................................................

They stopped at sunset for evening prayer. Adaryc knelt in the pale, dead grass at the side of the road. Beneath his knees he could feel that the ground was starting to soften; in Haligford they would be tilling the winter cover crops into the soil to prepare for spring planting.

He recited the familiar words, a prayer for protection and guidance, an affirmation of faith in the coming dawn; it was spoken twice, once for the living and once for the lost.

Too late he realized that kneeling had been a mistake; his limbs were stiff with exhaustion and unfolded only with spiteful reluctance.

“See what you have to look forward to?” Kae joked, offering him a hand up – at more than fifteen years his senior, the older soldier had had the sense to remain standing.

Kae looked as tired as Adaryc felt, the skin under his eyes was smudged dark like an bruise, and there was a hitch in his gait that hadn’t been there when they set out that morning; old wounds making themselves known.

The sensible thing to do would be to camp for the night and start fresh tomorrow morning, but —

He felt a stab of guilt at his own hesitation.

“We should stop while there’s still some daylight left,” he said at last, with more conviction than he felt.

There was a heavy sigh from Kae. “If it’s all the same, I’d rather push on through. Get this over with.”

“Your leg – “

“Will be fine. I’m old, not dead.” There was an edge to his voice, pain, weariness and tension all coming to a head, but his tone softened as he glanced sidelong at Adaryc’s bandaged arm. “If you need to rest–?”

Adaryc shook his head. He didn’t want to prolong this anymore than Kae did. They trundled the cart back onto the road and continued westward into the growing twilight. In the shallows of a nearby stream the frogs had begun to sing, their high-pitched chorus filling the air.

“Never did understand why he was so set on this,” Kae said suddenly after they had walked in silence for a short while. “I remember his family. He didn’t owe them a damn thing after the way they treated him. Don’t seem right, leaving him like this.”

It was an odd relief to hear someone say the words out loud; Adaryc knew it was selfish to begrudge Devet his last wish, but he couldn’t find a way to make peace with it.

“I gave him my word.”

“I know.” Kae was thoughtful for a little while, then he looked up, a fond smirk tugging at his mouth. “Were you there for — nah, you’d’ve been too young. The whole debacle with the honeyjack…. Gods, that must be what? Twenty-five years ago now?”

Adaryc shook his head. Devet had been in his mid teens at the time, so Adaryc wouldn’t have been more than six or seven. “It’s funny though – he told the story so many times, it feels like a memory. I can picture it clear as day.”

It had been a prank several months in the making. Devet and a friend had taken a small keg of wyrthoneg, the weak mead that was the only legal form of alcohol in Readceras, and over the course of a long winter cold snap, turned it into an ungodly strong honeyjack, which they had then used to spike the punch at the close of the midwinter holy days. They’d been caught, of course; Devet had spent a week in the stocks, nearly froze to death and was still considered lucky to avoid anything more serious, but even two and a half decades later, his eyes still lit up with mischief at each retelling. It was one of his proudest moments.

“It’s how we became friends.”

Adaryc looked up curiously. He hadn’t heard this part before.

“His family refused to bring him food while he was in the stocks. Too damn busy trying to distance themselves from the scandal, I reckon. So I started doing it. He was just a kid for fuck’s sake. Bit of an ass, sure, but who isn’t at that age. He was….” Kae was quiet for a moment. “He was alright. Haligford was just about bearable with him around.”

There was anther long pause and Kae added softly. “It ain’t right.”

<>

It was a few hours after dark when he heard the cries. It started with a single voice, calling out from the trees and Adaryc’s head snapped up, instinctively reaching for his sword.

The sound came again, urgent but indistinct. His eyes searched the darkness of the treeline, but by long habit, a portion of his attention lingered on Kae, measuring the sergeant’s reaction – the slight delay before he stopped and turned, the feel of his gaze shifting back to Adaryc rather than remaining fixed on the direction of the sound.

Adaryc let his hand drop to his side, but none of the tension left his body. The sound had been in his head: a spirit. In the early years this had caused no shortage of confusion and false alarms, but here, fifteen years later there was no need even for words. They read everything they needed from each other’s body language.

Over time Adaryc had grown better at compartmentalizing these encounters, of assessing and moving on, but that night his consciousness snagged on the voices like a cloak on a nail, wrenching him off balance.

Shame and self-loathing washed over him. To Readcerans, meddling with another’s soul was the ultimate act of blasphemy and hubris, and the ability to read souls was seen as a form of violation, on par with the more sinister abilities of cyphers. Such ‘gifts’ were considered a sign of a sick soul.

“Can you still see him?” The blunt urgency of the question startled Adaryc out of his own thoughts and he stiffened.

“What?”

“Devet,” Kae said simply. “Is he still… You know?”

“No.” It was more of a flinch than an answer, snapping out terse and defensive before he could stop himself.

He tried again, dragging in a breath and letting it out. The topic was less of a boundary and more of an open wound, a sin to be confessed. He spoke carefully, moving from word to word like someone treading on too thin ice.

“There were a few. On the way down from the mountains. But the burials put them to rest.” It wasn’t like after the war when the souls had clung to him for months, facing down specters of his dead friends every waking moment.

“But Devet —” He’d felt him go; felt him slip through his fingers even as he held his hand. He swallowed past the painful catch in his throat and thrust the memory away.

“He didn’t stay.”

Kae nodded solemnly. “He never was one for keeping still.” Adaryc couldn’t tell if he was relieved or disappointed.

“I wouldn’t keep that from you. If he was still —”

“I know. Just kept…. hoping, is all. He used to joke about it, remember? Coming back and haunting the parish.”

Adaryc cracked a weak smile, momentarily imagining Devet rustling pages and blowing out candles in the middle of a sermon.

“Now he’s got us doing it for him, the bastard,” Kai grumbled.

His tone was mild, joking even, but there was an edge of bitterness to the words as well.

The person Kae had lived as for thirty-five years was dead. He had buried them when he joined the war, and when he returned home with his head shaved and his breasts bound up, his family had thrown him out. As far as they — and much of the rest of Haligford — was concerned, Kae too was dead.

Adaryc’s own katabasis had been shorter by comparison, but more gradual. A slow immurement, burying himself alive brick by brick. A corpse walled up inside an effigy of what he was expected to be; in that way, they were similar. And there was a small, painful sort of catharsis in Kae’s offhand acknowledgement of it.

What was a haunting after all if not the dead returning?

They lapsed into silence for a time, following the road as it turned to run parallel with the river. The voices in his head had grown — not louder exactly, but sharper, harder to shut out. There were more of them now — it was always worse near bodies of water, worse too when he hadn’t slept — whispers pressing in from the periphery of his awareness.

Adaryc grit his teeth, striving to focus his whole attention on the sounds of the physical world around him, the creak of the wheels, the soughing of the wind in the trees overhead, the scuff of their footsteps.

The sound of running water.

All at once he was back amidst the desperate scramble to escape the flooding caverns of Ionni Brathr, the roar of the water all around them, the deadly slick of stone and ice underfoot, the crash of falling rock as the caves began to collapse on top of them. And then staggering out onto the ice floes of Cayron’s Scar and seeing it — all that red. Blood on the snow.

Beside him in the darkness, Kae began to hum and the memory drew back before the soft, offkey melody like shadows from candlelight. Adaryc recognized the tune, an old hymn that had been a marching song during the war. The memories it carried were bittersweet, but there was warmth and fellowship in them and the promise of morning no matter how long the night.

It was a small, quietly intimate act of care and Adaryc felt his throat tighten. He did not deserve Kae’s kindness.

.......................................................................................................................

Kae finds him huddled amid the crates and barrels and oil cloth tarps behind the supply tent. He is still shaky with adrenaline. His thoughts keep replaying the same scene over and over again. The physical examination. Standing naked together with the other recruits, the tight grip of the medic’s hands on his wrists, twisting them palms-up to reveal the criss-crossing lines of scar tissue, some not yet fully healed. The disdain in the priest’s voice as he calls into doubt his mental fitness, his commitment, his faith. He had wanted to die of shame. He had wanted to die. He wants to —

Kae sinks down on the packed earth beside him and Adaryc stiffens. His hands tug compulsively at his sleeves and his cheeks burn. He waits for the inevitable questions, the lecture, the platitudes, hot angry tears welling up in his eyes. But Kae doesn’t say anything. And for the first time it occurs to Adaryc that he is not the only one for whom the physical examination had been a forced confession.

For several long minutes they simply sit. Then, with a soft, deliberate exhale, Kae begins unlacing the cuff of his sleeve.

At first Adaryc doesn’t understand; he watches in confusion as Kae rolls up his sleeve to reveal the bare, brown skin of his forearm.

And then he sees them. Thin lines of slightly darker scar tissue, crosshatching the skin from his wrist almost to his elbow. The scars are old enough that they have begun to fade. They say, I understand. They say, it gets better.

.........................................................................................................................

They reached Haligford at dusk on the following day. Adaryc had sent a message ahead before they set out, though it could not have been much faster than they were. Still, some warning was better than none.

“Thought it would look different after all this time,” Kae remarked, the tension in his shoulders belying the evenness of his tone.

He was right. The buildings lining the road through the village were just as Adaryc remembered them. As if he’d been gone a few months rather than fifteen years. It filled him with disoriented unease, the same sort of dissonance he’d felt returning home after the war; the sense that he’d never left, that the war – everything he’d experienced – had never happened. Those who returned were expected to simply pick up where they’d left off.

Their somber procession drew no shortage of stares. But for the moment folk saw the weapons on their belts and steered clear.

“Never thought I’d feel skylined in a valley,” Kae muttered under his breath. It was a joke, but Adaryc felt it too. It wasn’t just the sense of being watched, he felt exposed.

It wasn’t until he heard the faint chuckle behind him that he realized he had instinctively quickened his stride to walk a few paces ahead of Kae.

“Taking point, Cendamyr?”

He let out a short exhale of a laugh at the kneejerk absurdity of it, but he didn’t drop back.

The forge was quiet when they reached Devet’s family home, but smoke was rising from the kitchen chimney. Devet’s sister, Deorhtric, answered the door, still in her leather smith’s apron, smudges of soot on her face. She regarded Adaryc’s travel stained gambeson and the sword at his side with open suspicion and then her gaze moved past him to the cart and her eyes hardened.

Without giving him a chance to speak, she turned and called two names into the house behind her and a moment later two men, whom Adaryc half recognized as husband and brother, joined them in front of the house. Behind them several younger, adolescent faces were just visible in the entryway.

“How did it happen?” Deorhtric managed to make the question sound like an accusation.

What could he tell her? They wouldn’t believe the truth — gods, he scarcely did and he’d been there. “A mercenary company from the Whitemarch was making trouble for villages along the border. We—”

“So my brother died so that you could have a dick measuring contest with another group of brigands,” she cut him off icily.

Adaryc went rigid. He could accept the blame — he was the commander, it was his responsibility — but not the way she dismissed Devet’s death as meaningless.

“He died protecting Readceras—”

She slapped him. The force of the blow snapping his head to the side. “Don’t you dare try to sell me that horseshit. In my own house. Over my own brother’s body. Your lies may have fooled Jora, but I know exactly what you are.”

It took every ounce of self control he had to simply take it. He straightened up, glaring, but she wasn’t finished. Kae had taken a step forward and her gaze fixed on him with sudden recognition.

“You’re that Haglund —”

“Leave him out of this!” Adaryc bristled. She ignored him.

“To think we took you in when you were turned out. And this is how you repay us? Though I don’t know what else I expected from someone who abandoned their family to play lackey for this —”

Adaryc took a sharp step forward, eyes blazing. “Kae is my right hand and one of the best men I’ve ever had the privilege of serving with!” he declared fervently.

“I think,” Kae interjected, calmly but with the finality of the Void, “Deorhrtic. You’ve forgotten who did the abandoning.”

And Deorhtric, to Adaryc’s surprise, stiffened, her face flushing at the quiet rebuke. But before any of them could say another word, another figure emerged from the doorway.

He had only ever known Devet’s mother from the occasional glimpse at the temple on holy days. She had always seemed stern and imposing. From the stories Devet told, she had been the very image of sober propriety; Devet had been her youngest and a perennial disappointment.

It was difficult to reconcile that image with the old woman before him. She was smaller, frailer, and there was a softness to her that was entirely alien to the person she had once been. It was generally accepted that Berath granted kith the mercy of forgetting their past lives at each new turn of the Wheel, but some folk were cursed to begin before that.

The son-in-law turned to her with a mixture of annoyance and concern, urging her to go back into the warmth of the house, but she was insistent.

“Who’s that?” she demanded peering at Adaryc and Kae before spotting the coffin and shrinking back a step, “What do they want?”

“They’ve brought Jora home, Mother.”

For a moment the old woman’s expression brightened, the thought of the coffin displaced by the familiar name. “He’s coming home?”

The husband made another attempt to coax her away, but the sister shook her head. “He’s dead, Mother. Jora is dead.”

Adaryc saw the horrible, frightened confusion on her face as the words slowly sank in. And then she began to weep, a quiet, shattered wailing as she sagged against her daughter.

Deorhtric fumed, keenly aware of the faces that had begun to appear in the doorways and windows of their neighbors’ homes. “Didn’t even have he decency to bring him ‘round the back. Had to drag him through the street like a common criminal – Oh for gods’ sakes!” she rounded on the husband and brother who had begun to argue over where to put the coffin. “Put him in the foundry. It’ll keep until sunrise.”

The brother together with one of the adolescents loped off to prepare space, leaving them with nothing to do but wait.

The sister stood, still supporting her mother, her glare now fixed on the coffin itself. “You see children, this is what comes of foolishness. Folk who think only of themselves come to a bad end.”

A small crowd had begun to gather by this point and Adaryc could only stand there, anger choking in his throat. He planted himself in front of Kae — though his slight frame made for pitiful cover. Most of those gathered spared them only wary, disapproving glances, but one man kept looking at Kae, brow creased as though trying to place him. Adaryc turned toward him, meeting his surprised stare with such aggressive directness that the man turned away in discomfort. Behind him he heard a soft snort from Kae.

In the midst of it all, the old woman withdrew from her daughter and approached the cart. She pressed her trembling hands to the coffin, smoothing or wiping away something only she could see. Did he suffer? she wanted to know. And he did his best to answer. But she could not hold onto the words. She would go back to fingering the coffin and a few moments later the same question again. How did it happen? Did he suffer? Was it painful? Each repetition felt like a knife twisting in his chest.

After what felt like hours, the brother and apprentice returned, ready now to take charge of the body, and Adaryc and Kae were free to go.

Adaryc had had days on the road to brace himself for this, but it still hadn’t prepared him for how much it would hurt. The panicked sense of rage and desperation as the finality of the loss began to sink in.

Grief snapped and snarled like a wounded animal inside his chest. He’s not yours! He had the irrational impulse to grab hold of the cart, to drag Devet away, away from these people and this place that had never wanted any of them. But what he wanted didn’t matter. This wasn’t about him, it was about Devet, and he’d promised Devet he would return him to Haligford.

They left the wagon with the family — the body still needed to be transported to the temple — and headed back the way they had come. The silence was so much emptier; it felt absurd to miss the rattle and jarring of the cart, but it had been almost like a third presence on the road. Now it was just the two of them.

The quiet grew more strained with each step they took. The road seemed narrower, the buildings closer.

Kae scrubbed a hand across his face, breathing out a long sigh once they passed the last house. “Well. That was shit.”

Adaryc exploded, “They had no right! They talked like he deserved it for fuck’s sake! He changed and left and now he’s dead because ‘that’s what happens’. As though this somehow puts things right! Puts everything back to ‘the way it should be’!”

It felt painfully familiar. He remembered the way some villagers had looked at them after the war, at their difficulty re-adjusting to life in the village, as though they were nothing but walking reminders of Readceras’ failure, as though it would have been more convenient – more comfortable – for everyone if they’d died with their god.

“All he’ll ever be to them, all they’ll allow him to be remembered for is a cautionary fucking tale about how you should never change and never leave and never question and just keep fucking pretending that everything around you isn’t on godsdamn fire —” He broke off breathless, so angry he was shaking.

“They don’t matter,” Kae retorted with sudden vehemence. “They aren’t the only ones who will remember him. They got a body. That’s it. They got meat and bones. We got fifteen fucking years. We got him. We got first blood and last breath and everything in between. They don’t fucking matter.”

Adaryc let out an unsteady breath. Kae was right, though in the moment it was small comfort. They walked in silence for a few heartbeats before Kae added. “And if you let my family anywhere near my remains, I will haunt you from Hel to breakfast.”

The remark startled a small, mirthless laugh from Adaryc, but he quickly sobered. “Your family – did you see them?”

“Not yet.”

“Is that better or worse?”

Kae sighed. “Bit of both? There’s a piece of me that gets to wondering sometimes if maybe they’ve changed. I know the answer, but I don’t know, you know?”

“Yeah,” Adaryc admitted quietly. He did.

<>

The burial was set for sunrise the following morning, as was traditional for Eothasian rites.

Adaryc and Kae camped at the edge of town. Darkness had begun to fall by then, softening the unsettling familiarity of their surroundings. In the dark, Haligford and its environs could have been almost any other farming village in Readceras.

There was some comfort in the routine, in the physical acts of gathering water and wood, of scouting the perimeter, in preparing food, in pestering Kae into using the salve Marwyd had given him for his knee, and being nagged in return about his arm. A connection to their life outside of Haligford, to the Flail.

It unnerved him how far away that life felt here and how little he felt like the person he had fought tooth and nail to become. It had been fifteen years; he was a grown man, the commander of a collective of soldiers; he’d survived a war, dozens of skirmishes with mercenaries and bandits, the Eyeless, he’d negotiated with Glanfathans, defied wealthy landowners, stood before the damned Morning Council…. And all it took was a name — mentioned offhand by Devet’s brother arguing with Deorhtric over the funeral arrangements, and all the fear and anger and helplessness came flooding back as if he were a child again.

Homecoming was meant to be a consummation, a joining that made one whole again. But it wasn’t. The person who returned was never the same as the one who left, and there was no reconciling the two. There was just the struggle of one over the other and the slow annihilation of self.

They ate in silence — journey cakes Kae had made with a mix of cornmeal, salt and water, cooked on a stone over the fire. The news that Brother Haemon would be presiding over the burial had them both on edge; Kae smoked and Adaryc fidgeted; nerves turned the food to ashes in his mouth and it was all he could do just to keep it down.

When it came time to bed down, Adaryc took the first watch, staring into the shadows beyond the fire until the restless, skin-crawling sense of waiting grew too much to bear and he got up to walk the perimeter.

“Seen you less on edge before a battle,” Kae remarked when Adaryc returned to stand by the fire for the dozenth time.

Adaryc’s brows quirked upwards, glancing over at where Kai lounged, propped against a tree. “You’re one to talk. How many pipes has that been now?”

There was a low chuckle from Kae. He’d been smoking like a chimney since they’d made camp.

“If I’m honest, a battle would be preferable,” Adaryc admitted, tugging compulsively at his sleeve with his good hand.

“Rymrgand’s frozen ass crack would be preferable.”

Adaryc choked on a laugh, shifting his weight from foot to foot. Despite the warmth of the fire, he couldn’t stop shivering.

“Suppose it was too much to hope that old Haemon would have passed on,” Kae sighed. “Bastards like that are always the last to go. They’re like cockroaches. Kick over enough rubble in an abandoned temple and one of the fuckers would probably come skittering out.”

They had both been Haemon’s ‘favorites’ at different times. Though ‘projects’ might have been more accurate. The ones he took a special interest in. The troubled children who needed to be broken in order to ‘heal’ properly, like a mis-set fracture.

........................................................................................................................

“Your father tells me that you have been shirking your chores.”

The priest smells of tallow and incense. He towers over Adaryc’s eight year old frame where he stands in the flickering light of the altar candles with his hands clasped in front of him, his face hot with shame.

It sounds so much worse, so deliberate when Brother Haemon says it. Adaryc wants to deny it, to explain — He’s not lazy, it’s just…..he’s just….. but there’s no word for the emptiness that has displaced the person he used to be. He feels numb. He feels hollow. His brother has to drag him out of bed every morning. All he wants is to sleep. Tasks that he used to complete quickly now take him ages, if he remembers to do them at all. What is that if not laziness?

“He also tells me that you have not been eating.”

Adaryc’s shoulders hunch a little more. Laziness and ingratitude.

“Is something troubling you, child?”

And because he trusts him — because he has been taught to trust him — he tells him. Or tries to. Feeling clumsily for the words like someone groping for a path in the dark.

Brother Haemon listens patiently. “You are unhappy,” he says at last and Adaryc feels a rush of relief, imagining in that brief moment that he understands.

“Unhappiness is selfish, Adaryc.” The words hit him like a physical blow.

“Just like doubt. The more you indulge it, the more you give in to those feelings, the more you invite misfortune. Do you understand?”

He doesn’t understand. An apology, like a flinch, rises to his lips. I didn’t mean to. I didn’t want to. I didn’t – And then his mind processes the rest of what the priest has said and he goes very still.

“What – what kind of misfortune?”

“Do you think that is the question you should be asking?” The priest’s tone is indulgent, a threat concealed in an invitation, and Adaryc shrinks into himself a little more.

“No, but —” he stammers, pressing forward desperately, “But I mean – it wouldn’t be things like – like the vorlas? Would it? I mean, other people wouldn’t be — they wouldn’t be punished for something I did. Would they?”

Fear clamps around his chest. The words he doesn’t dare confess lodge in his throat until he feels like he might choke. The vorlas in the south fields is failing. They found the first sick plants shortly after his own troubles began.

The priest places a hand on his shoulder, and for an instant the panic subsides. He looks up anxiously, seeking reassurance. And Haemon crushes him like a moth. “Misery begets misery,” he intones. “If a well is polluted, do not all who drink from it become ill? Do not the plants watered by it wither?”

Guilt floods Adaryc. The crops are dying, because of him. His father won’t be able to pay off his debts, because of him.

He feels hot and cold and dizzy at the same time. He feels like he’s going to be sick. If his father and brother find out…. If they knew it was his fault…. If they knew how wicked and lazy and ungrateful he has been…

“What cause do you have to be unhappy?” Haemon adds in the same honey-coated tone. “You have a roof over your head, a father who puts food on your table, you are healthy in body, as are your father and brother. You have much to be grateful for, child. Take joy in those things, repent your ingratitude, and all will be well.”

All will be well. Adaryc cleaves to those words with the desperation of someone drowning. There’s still a chance. He can still fix this. He can make it better.

When he returns home he greets his father with a smile; he completes his chores without prompting, and he eats his dinner with apparent enthusiasm. His brother, Eadwyn watches him, his face an open question, but Adaric doesn’t meet his eyes.

<>

He tries so hard to be happy. He performs normalcy like a prayer — as if conviction alone can make it real. And when that only makes it worse, when the isolation and the fear are more than he can take, he turns his lies in on himself. The numbness, the exhausting heaviness, that is all normal, he tells himself. Everyone feels like this. He just needs to get used to it. He needs to be stronger. Doubtful thoughts clamor in his head and he tries to drown them out with other thoughts, better thoughts. He prays every night.

But the harvest still fails, and guilt and fear take root in his soul like bittersweet vine.

During the winter season, the children of the parish who can be spared from work attend lessons at the temple. One day he asks why Eothas doesn’t answer prayers. That is the wrong question. Brother Haemon makes him spend the rest of the lesson kneeling on the stone floor in view of the other children as punishment.

After the lesson, the priest pulls him aside, interrogating him on the reason why he would believe such a thing.

Adaryc learns that this, too, is his fault. A lack of faith. A lack of sincerity. If he had faith, if he truly believed without any doubt that his prayers would be answered, then they would be. It is as simple as that.

His prayers grow obsessive, lying awake at night repeating the same request over and over. There is always some imperfection. Nothing feels sincere enough, the smallest flicker of distraction or doubt poisons the whole attempt and he must begin again.

It feels like praying to a wall. But he keeps trying. Again and again. And again.

He barely sleeps. His emotions begin to swing violently, often over the smallest things, and he feels less and less in control.

Thoughts that seem to belong to someone else begin to thrust their way to the front of his consciousness; frightening and obscene, and the harder he tries to shut them out the louder and more persistent they become. They are there in every prayer, every sermon, every quiet moment.

He begins to believe that his soul must be stained somehow. That he must have been a truly horrible person in a past life. And it is that person’s thoughts and impulses bleeding through into him. It explains everything – the terrible thoughts, the violent outbursts, the periods of emptiness.

It explains too why his god never answers. Why he never seems to be there in the ways that the sermons and prayers promise. If thou art broken, he shall make thee whole, they say. If thou art in darkness, he shall bring thee to the light. If thou art sinful, thou shalt be reborn. If thou art cold, his warmth shall bolster thee.

But they also say: If thine heart be black, if thine intention be impure, thy life is forfeit. For he hath seen, he can see, he will see. Nothing is hidden from his glory.

Eothas had seen his soul and what he saw there was so monstrous, so unforgivable, that even the god of redemption had turned away. It is the only explanation that makes sense.

.......................................................................................................................

It was still dark when they broke camp. Neither of them had gotten any sleep, but propped against each other back to back by the fire they had managed something resembling rest.

Adaryc splashed water on his face, combed his fingers through his tangled mess of hair; he’d forgotten his razer and Kae didn’t own one. He turned instinctively to ask Devet — only to stand there, paralyzed for several heartbeats, staring at the empty space across the firepit.

He hadn’t learned how to use a razer from his father. When his first beard started to come in during the war, it had been Devet who took pity on him and showed him how to shave without cutting up his face. He remembered his own clumsy embarrassment, Devet’s easy manner soothing his ruffled feathers, he remembered the intimacy of allowing another person to hold a blade to his skin, he remembered feeling safe.

He tugged his rumpled clothes straight with his good hand – his left still hung useless in its dirty, makeshift sling – and straightened up, schooling his features into something he hoped to the gods passed for composure as he turned to Kae and nodded.

They didn’t speak on the walk into the village, their breath forming clouds in the cold morning air. The fields on either side of the road were grown over with vetch and winter rye; a few had been freshly tilled. The spring planting would begin soon and he felt a familiar anxiety tighten in his chest.

Let it be a good year, let it be enough. He murmured the prayer out of habit, and guilt came back like an echo; the fight he’d had with his father on the night that he left for good – if he’d truly cared, then he would have stayed. Your brother would never have turned his back on us. Tired shadows skittered at the edges of his vision and he scrubbed his hand over his eyes, feeling angry and slightly sick.

To the north, the silhouettes of large outbuildings began to rise out of the rolling hills and Adaryc’s jaw tightened.

The Dal’geys estate was a large manor farm that grew larger with every bad harvest and increase in taxes, purchasing the land from the parish when the families that owned it could not pay their taxes, and then allowing them to continue working the land as tenants. The practice had been active under the Aedyran government, but had become increasingly common since the war.

Dal’geys was, by all accounts, a deeply pious man. This meant that he gave generously to the temple with the gold he made off the backs of his slaves and tenants, and precious little else.

In the early years of his marriage, Adaryc’s father had borrowed money from Dal’geys to save his farm, and indentured himself to pay it back. He still lost the farm, and in order to pay for rent and food, he’d had to borrow more. When the four year contract ended, he was more in debt than when he’d started, and the cycle began again.

His father had never recovered from the loss, nor from the sense of failure and shame that accompanied it. In the social hierarchy, indentured laborers were only slightly higher than slaves; he had lost not just his land and independence, he had lost his place in the community.

It ate away at him, but even in the days before Adaryc left, his father still never fully accepted it. The priests taught that patience and hard work would be rewarded, he simply had to have faith.

Have faith.

An old, bitter anger welled up in Adaryc, painful like a wound left to fester. It was convenient – the way poverty and bondage were framed as moral failings. His father had worked himself to death and died alone without a copper to his name, not because he had been conditioned and exploited all his life by those with more wealth and power, but because his faith was insufficient.

What did they know of faith? To them it was nothing but a shell game to keep folk in their place. To blame the slave for his chains and the pauper for being poor.

But Dal’geyss was a pious man.

It was enough to drive a man to arson.

Out of habit Adaryc turned to look south across the fields on the other side of the road, his gaze finding the small smudge of a building more by memory than by sight. There was a light in one window. And for just a heartbeat his father was alive again.

Adaryc froze, reeling from the whiplash of hope and loss. There was a new tenant. Of course there was. It was idiotic to think that —

He swiped a sleeve across his face, furious with himself for the homesick grief strangling in his chest. That place had never been home. His father had been dead for three years and out of Adaryc’s life for even longer. They hadn’t spoken since he’d left Haligford. Adaryc had tried to write him, whenever he saved up enough to send home, but his father had never replied, and eventually the letters had become nothing more than receipts listing the amount of money contained within. Twelve years of silence. Twelve years.

........................................................................................................................

There is no warning, just a road weary messenger appearing like a bolt from the blue with the news that his father has died.

Adaryc is with a squad of his men, helping the villagers of Brightwell clear land for new fields, when the messenger arrives. He hears Devet’s bark of laughter and glances up to see him approaching with another man.

“Messenger for you. Called me ‘Commander’,” Devet grins. “Better watch your back, Cendamyr, I might start getting ‘ambitions’.”

Adaryc’s mouth crooks. They’ve been serving together for twelve years and Devet has steadfastly refused every single promotion Adaryc has tried to offer him.

He turns his attention to the messenger.

“You are Adaryc Cendamyr?” he asks, eyeing Adaryc’s muddy, sweat-stained appearance with undisguised misgivings.

“I am.”

Adaryc takes the letter that the man hands to him and cracks the seal, his hands leaving smudges of dirt on the crisp, white paper.

He stares at the two sparse sentences for a long time.

‘It is with deep regret that I must inform you that your father, Meryc Cendamyr, after long struggle, has succumbed to his illness. May his soul return soon from the Wheel.’

He looks up, his shoulders straightening with a small jerk as he addresses the messenger; he tries to keep his voice neutral, but it comes out stiff and officious instead. “Was there anything else?”

The messenger shifts awkwardly. “The priest said you would cover the fee. That you were good for it, on account of some highborn patrons.”

Adaryc stares at him. Standing there, covered in sweat and mud, in his plain, much-mended clothes and travel worn boots, he feels the absurd, horrifying urge to laugh. The messenger, at least, has the good grace to look uncomfortable.

It is true that they have a few supporters in high places, it is also true that that support is what allows them to continue working in a region where most folk are too poor to pay them. But of course the old priest assumes he’s lining his pockets with it.

It is a moment before he trusts himself to speak.

“How much?” Moving mechanically, he pulls his purse from his belt and upends it into his hand. It is painfully obvious that the small handful of coppers isn’t enough.

In the end he has to borrow the difference from Devet.

“Bad news?” Devet has been watching him closely, but waits until the messenger is gone before speaking.

Adaryc hands him the letter.

The paper crackles as he unfolds it, then – “Effigy’s eyes…” Devet looks up, his normally merry face suddenly serious.

“I didn’t even know he was sick.” It feels like such a small, useless thing to say.

“Adaryc–”

He almost never uses his given name. Always his surname or his rank. And somehow the small act of intimacy affects him more than the letter itself.

“If you need to – “

“No.” It comes out harsher than Adaryc intended and he grimaces. “He’s beyond anyone’s help. This place isn’t.”

Devet looks as though he wants to protest, but instead he places a hand on Adaryc’s shoulder and turns to address the rest of their squad who have been staring curiously ever since the messenger arrived.

“Alright, back to work. Ondra’s tits, I swear y’all are nosier than a village priest.”

...........................................................................................................................

The roof of the parish temple rose into view above the trees, a great, dark shape crouched atop the nearby hill. Adaryc’s hand brushed his belt, feeling reflexively for Steadfast, but there was no comfort in the unfamiliar hilt that hung there now.

As they neared the top of the hill, they skirted the perimeter, entering instead through the gate at the back of the cemetery. Little had changed in fifteen years, save for the new stones which always stood out with such stark nakedness from their lichen encrusted elders. Bright green growth was beginning to peak through the dead winter grass and thick beds of moss cushioned their steps.

They were early. The family wouldn’t be there for a little while yet. Enough time to pay his respects.

He left Kae smoking his pipe in the lee of the transept and made his way into the churchyard. An uncomfortable resonance surrounded him the deeper he went, like a bass string so low and heavy that it no longer registered as sound; whispers tugged at the corners of his mind, echoes of souls still lingering.

His family plot was small, tucked away beneath a whitethorn tree in the northwest corner. The stones were unmarked. Just small fieldstone cairns. Engraving had been far beyond the means of an indentured laborer.

He knew them by memory. The long, low cairn now grown up with weeds was his mother’s, and the two smaller, but higher piles beside it, crusted with lichen and moss belonged to his brothers, little Inri and Eadwyn the eldest. There was a a fourth cairn now as well. Almost pristine in comparison to the others.

He was not sure what he had hoped for, standing before his father’s grave. Some kind of closure, a place to set down the guilt he had carried for so long, for leaving, for not having been there. But the stones were as stubbornly silent as his father had been in life, and he found only questions with no hope of answer and the gnawing, helpless anger of old wounds.

There had been a time before despair and loss and exhaustion had hollowed his father into the bitter, passive shell of a man that he became. In some ways that made it harder. The knowledge that none of it was set, that it might have turned out differently. After everyone he had buried over the past weeks, it felt absurd to grieve for that, for a version of events that had been just a little easier, a little kinder, when there were bodies in the ground, but —

But.

He just wished —

Adaryc scrubbed a hand over his face. He did not doubt that his father had, in his own way, harbored some degree of attachment, perhaps even affection for him. But in the end, Kae was right: love was not a feeling, it was an act.

He let out a long, slow breath. It wasn’t relief, or closure, he was not even sure it was acceptance, but it was an end, of sorts. An acknowledgement, however painful. He knelt on the cold ground, the morning dew soaking through his leggings, and with the little time he had left, he began to remove the worst of the dead grass and weeds from his mother and brothers’ cairns.

He had few memories of his mother. She had died of the same fever that took Inri when Adaryc was only two winters. Her name was Sigge. Eadwyn had sometimes shared stories about her when they were young, but his father scarcely spoke of her at all, except in censure, until Adaryc could no longer separate his memories of her from the sting of his father’s disappointment.

Thank the gods your mother didn’t live to see this.

What would your mother say?

Taking out his knife, he began to scrape some of the lichen from Eadwyn’s cairn, murmuring a prayer that the gods might bless him in his next life. There wasn’t enough time to do it properly, but there was a ritual of care to the act which felt right. A reversal of sorts. Eadwyn had always been the one looking after him.

........................................................................................................................

He is two winters, clinging tightly to Eadwyn’s hand as they stand in the small crowd gathered round an open grave. Something terrible has happened, he can absorb that much from the tearful adults around him, and it frightens him. He wants his mother, but his father gets upset when he asks for her now; he says that Mother and Inri are gone. Adaryc knows they are gone; he saw the man in the dark robes come and take them away. But he wants them to come back.

He starts to cry and Eadwyn scoops him up and holds him against his chest. His brother is trying desperately not to cry, but his cheeks are wet when he pulls Adaryc close. Adaryc huddles into him, burying his face in the crook of his neck. His brother is warm and familiar, an island of safety amidst all the strangeness.

<>

He is six winters, sitting at the table on a snowy night, the warmth of the hearth nearby and the chill of the draft at his back. He can just make out Eadwyn’s face in the glow of the reed light, twisting into silly expressions as they make a game out of trying to make the other laugh while their father’s head is bowed in prayer over their meal. He always catches them of course, that is part of the game, a faint glint of amusement in his eyes softening his censure.

<>

He is ten winters and his world is falling apart. Two years of guilt and fear and secrets, two years of watching bad things happen to the people he loves and knowing that he is to blame. And now Eadwyn speaks of nothing but leaving, of apprenticeships, of jobs in the city, of far away places. Their father will hear none of it, so he confides in Adaryc when they are alone together, his eyes bright with eager determination.

But Adaryc is too absorbed in his own troubles to see how unhappy his brother is, how heavily the burden of their father’s hope weighs on him, the pressure of being the eldest son and second parent, the ‘good child’. All he can see is that his brother wants to leave him.

“But you’re coming back, right?” he asks him after Eadwyn has rambled excitedly about how much more money he thinks he could make from just one season of work in the city.

Eadwyn shrugs a noncommittal affirmative. “You could always come with me!” he grins.

And for an instant Adaryc believes it. But his mind is so deeply mired in old patterns of self-loathing and rejection, that hope just feels like another kind of fear and he shrinks from it, a knee-jerk objection springing to his lips.

“What about the farm? And Father?”

He regrets it immediately, but it is too late. Eadwyn’s face closes off and with a frustrated sigh the conversation is over.

In the end, Eadwyn doesn’t go. A new section of land needs clearing and all hands are needed if they’re to have it ready for planting in the spring. Next year, he swears, he’ll go next year, but there is always another catch, another disaster or delay that forces him to hold off for just one more season, just one more year.

<>

He is twelve and he can’t do this anymore. One winter’s night, letting the bucket fall from his hands as he steps into the ice cold waters of the stream behind their cottage. The water is so dark that he imagines he could fall into it and disappear completely. Wiped from existence like ink spilled over a page.

The cold hurts at first. The shock of it against his chest makes his breath come in violent, spasming gasps. And then, gradually, the pain begins to fade, and his breathing slows. He isn’t shivering anymore. He isn’t even cold. His thoughts are sluggish and indistinct. He tries to imagine falling forward, it would be so easy to just slip beneath the surface.

Vaguely, as from a great distance, he is aware of someone shouting, the sounds of splashing water, and then there are arms around him, and the last thing he is aware of before he loses consciousness is warmth.

Warmth is how he remembers Eadwyn. Not the bright, sunny warmth of a summer’s day, but deep and quiet like a sun-warmed stone at evening.

“I told Father it was an accident,” Eadwyn confesses the following night, whispering as they lay huddled under threadbare woolen blankets on a shared pallet, “That you were fetching water and fell in.”

Adaryc’s shoulders hunch guiltily and he murmurs a half-hearted thanks. In the dark, he can feel his brother’s eyes on him, the painful, searching question in them as the silence between them pulls taught.

“I don’t understand. Why didn’t you tell me? We used to – we used to talk. And now…. I don’t know what happened, you’re so far away. I can’t help you if you don’t talk to me.”

In that moment Adaryc wants to tell him. He wants to believe that even after all the harm he has caused, all the poor harvests, the sick crops, the debt, the fights, Eadwyn’s own crushed dreams of escape, that his brother would forgive him.

He wants to believe. But he can’t. Tears roll down his cheeks and with a soft sigh, Eadwyn pulls him close. They stay like that until morning.

<>

He is fourteen winters, staring at the empty seat across the table. His father says the evening prayer as though nothing has changed, as though nothing is wrong, and he feels like he is drowning. Because Eadwyn is dead and it is his fault.

“Effigy’s eyes —” he blurts out angrily, interrupting the prayer. “He’s not listening! He doesn’t care!”

His father looks up, for a moment too startled by his outburst to even be angry. “Of course he does. But sometimes…..” He falters for a moment, his gaze not quite meeting Adaryc’s. “Sometimes Eothas sends us trials to temper our faith. To strengthen it.”

Adaryc stares at him in disbelief, angry tears welling in his eyes. “You don’t believe that – you don’t believe that Eadwyn died just so god could prove a fucking point!”

“Adaryc–”

“Everything is so hard all the time and you keep saying it makes us better but it doesn’t! It doesn’t! Look at you – all you’ve ever done is bowed your head and rolled over! To god, to the temple, to Dal’Geyss. That’s not faith, that’s – that’s — “

“Adaryc!”

“What is the point? To see how far he can push us before we break? Eothas sounds more like a landlord than a g–”

It is the first time his father has ever struck him in anger.

He remembers the look of shock and regret on his father’s face, the struck-match, incandescent outrage in his own chest. In time, he might have forgiven him for that. But not for what came after.

“Enough!” his father barks, retreating once more to his seat at the table. His voice is rough and fraying at the edges and he does not meet Adaryc’s eyes. “That’s enough. Now sit down and finish your dinner.”

Sit down and finish your dinner. Sit down and pretend that this never happened. Pretend that your grief isn’t eating you alive. Pretend that you accept it – Eadwyn’s death, the blight, the sickness, the hunger and exhaustion, the landlords and slaveholders with their soft hands and big houses. Pretend that you believe all that suffering makes people better. Pretend that the temple sermons fill you with certainty, and the hymns kindle your faith. Pretend that you believe your god answers prayers. Pretend that you aren’t a monster. Pretend that you aren’t hemorrhaging rage and doubt and pain and all the ugly, selfish emotions you’ve tried to pretend for years that you don’t feel. Pretend. Pretend. Pretend.

.......................................................................................................................

Adaryc heard a step behind him and looked up to see Kae approaching. The rite would be starting any moment.

He pushed slowly to his feet, his gaze lingering on Eadwyn’s grave. He found himself wishing suddenly, painfully, that he could have told him. That night after Eadwyn pulled him from the stream, he wished he could have explained, could have trusted him. He thought —

He thought that he might have understood.

<>

The family were already gathered at the east side of the temple yard, a small crowd, maybe a dozen sober-faced scelterfolc, and a few children too young to have ever met Devet, looking bored or curious by turns. And slightly apart, standing over Devet’s coffin —

It didn’t matter that he’d been bracing for it. Adaryc’s gait hitched as Brother Haemon looked up at their approach, and it was only Kae’s presence at his back that kept him from freezing up like an unblooded recruit.

He steeled himself as the priest broke away from the family and began to approach the two newcomers. “Adaryc–” The use of his given name felt like a belt across his back and he hated himself for the reflexive obedience with which he responded, shoulders snapping straight as if he were still the same troubled child, being pulled aside after lessons for the hundredth time.

“This is a surprise. I thought you’d become too grand for Haligford.” Adaryc’s face reddened at the familiar barb, but he bit his tongue, acknowledging Haemon with a stiff nod.

“Brother.”

“It’s good of you make the journey, this time.” Unlike when your father died, the implied censure was plain in his face and tone of voice, and Adaryc stiffened. Out of the corner of his eye, he saw Kae shift, his hands in loose fists resting just below his breastbone. A simple change in posture, but he recognized the veiled aggression behind it and felt desperately grateful for the brief moment of catharsis.

Haemon must have caught his glance because he turned to Kae, and Adaryc saw him pause, struggling to place him just like the man the day before.

Adaryc opened his mouth to interject, but even Brother Haemon wasn’t immune to Kae’s ‘go ahead and try me’ stare; he turned away with a disdainful sniff and, taking his leave, returned to the graveside.

They waited there, in the cold shadow of the temple, restless and silent save for the occasional murmur of the younger children. At last the first rays of sunlight could be spotted cresting the horizon and the priest began to recite the Eothasian blessing for the dead. A censer swung from his hand, burning incense to mask the smell of decay. It smelled like guilt and fear and Adaryc found himself caught in a visceral sense memory of kneeling before an altar bright with candles, whispering the same prayer over and over and over again, stumbling each time as a sliver of doubt or distraction found its way in, never quite right, never quite enough, like a nightmare where he keeps trying to run and his legs won’t work.

He dragged his eyes away from the censer, focusing instead on the coffin where Devet lay.

He had told Devet’s mother that he had died in battle, that it had happened so fast it would have been over before he knew what hit him. He hadn’t suffered. He’d assured her of that.

Lying was a terrible sin. But what possible peace could there be in knowing the truth? That her son had died of his wounds on the return journey, that it had been slow and lingering, that the first amputation hadn’t been enough, that the infection had come back, that by the time he died he was out of his skull with fever and sobbing like a child, begging someone to make the pain stop.

Adaryc had held his hand until he grew still, and he’d kept holding it long after that.

He blinked, swallowing past the tightness in his throat. As the blessing ended, Devet's sister guided her mother to the grave to lay a spray of bloodroot and anemone atop the coffin. That seemed to be the sign for the sexton and her assistant to lower the body into the grave, and Haemon began to recite the prayer of mourning.

Adaryc closed his eyes. He’d said the same prayer over so many graves in the past days that he knew it by rote. He tried to take refuge in the familiarity of the devotion, but the words felt cold and distant, and for the first time in a long time, prayer felt like standing on the wrong side of a locked door.

“Is there anyone who would speak for Jora before he is laid to rest?”

Adaryc’s mouth felt suddenly dry. He should have been prepared for this. “Adaryc?” It was the same tone he had used when calling on wayward children during lessons, catching them out for not paying attention.

It took all his nerve just to pry himself away from Kae’s reassuring proximity. He had the sudden, irrational impulse to ask the sergeant to come with him, like a child afraid of the dark.

He drew himself up, standing parade-ground straight, painfully aware of how he must look with his travel stained clothes and cheeks rough with several days’ stubble.

Brother Haemon took a step back, beckoning Adaryc to stand beside him, not allowing him to keep his distance. His face a cooly benevolent mask as he reached out to rest a hand on Adaryc’s shoulder.

Adaryc flinched, shoulders involuntarily twitching away from the touch, and his face went scarlet. Everyone had seen that. He could feel the familiar, disapproving weight of the priest’s gaze, and as he looked down at Devet’s coffin, he felt suddenly absurd, a toy soldier, as if the Iron Flail was nothing more than a story he’d made up about himself.

“Devet was –” His mouth opened and shut; each word that he reached for felt more hollow than the last; a performance of respectability, of expectation. Devet wasn’t in those words.

Devet wasn’t here.

There hadn’t been time for mourning. There hadn’t been time, and now it was too late, Devet was in a box at the bottom of a hole; he would never see him again, never say goodbye. There hadn’t been time for mourning and now it hit him all at once. His throat tightened and tears spilled over, and all he could think of was those first few days after the amputation, how he’d seemed to recover. He had been getting better, he was supposed to get better, and then –

Out of the corner of his eyes, he saw Brother Haemon step forward as though to usher him away, the words of the final benediction already on his lips, “Eothas, light of spring — “

“I wasn’t finished.” The words came out in a snarl, bristling like a wounded animal, old wounds torn open, flooding him with long festering anger.

There was a reason that the only way Devet could come home was in a box. That was the only version of him, of any of them, that this place would accept.

“I know you think Devet was wrong,” he choked the words out, his voice still rough with emotion. “That he strayed from the path – or was led astray. You think that the life he chose was a sin, a mistake. That he was selfish for choosing to leave.

“Which is pretty fucking rich coming from folk who expect their own children to break themselves into pieces just so the rest of you can feel comfortable!

“There’s folk – a lot of folk – in this world who still have breath in their lungs and roofs over their heads because of Devet, because of what he did. Gods know I’m one of them, must have saved my skin a dozen times at least —

“He mattered. What he did – what he chose to do – mattered.”

For a moment he stood there defiantly, blazing like a torch, before the fire in his eyes guttered and he turned away. His heart was beating wild and erratically and all he could hear was the sound of blood rushing in his ears as his field of vision contracted to a narrow, distant sphere. His legs kept moving but they seemed to belong to someone else.

He walked until Kae’s arm caught him across the chest, gently but firmly corralling him.

“Slow down. You’re alright.” Kae’s hand shifted from his shoulder to the back of his neck, pulling him in. “You kicked a hornets’ nest there, boy,” he chuckled.

Adaryc couldn’t stop shaking, but he let himself be held, leaning his head against Kae, breathing in the familiar scent of pipe tobacco, feeling the even rise and fall of his friend’s chest as his own ragged breathing began to slow.

........................................................................................................................

There is a joke among some of the old soldiers – that no combat-ready company ever passed inspection, and no inspection-ready company ever survived combat. And it seems that a holy war is no exception. The closer they get to the front line, the less pretense and appearance seem to matter; no one in his company cares how he feels about standing watch or fighting or tending injuries, they only care that he does it, and does it competently. They care that he works hard and learns fast. No one asks him to pretend.

Bit by bit his defenses lower and his shoulders come down from around his ears. He learns to stop looking for mockery and rejection in every face around him and, to his bewildered surprise, discovers that some of them actually like him, and he likes them. He has friends.