#Thomas Crowther

Text

The potential of newly created forests to draw down carbon is often overstated. They can be harmful to biodiversity. Above all, they are really damaging when used, as they often are, as avoidance offsets— “as an excuse to avoid cutting emissions,” Crowther said.

The popularity of planting new trees is a problem—at least partly—of Crowther’s own making. In 2019, his lab at ETH Zurich found that the Earth had room for an additional 1.2 trillion trees, which, the lab’s research suggested, could suck down as much as two-thirds of the carbon that humans have historically emitted into the atmosphere. “This highlights global tree restoration as our most effective climate change solution to date,” the study said. Crowther subsequently gave dozens of interviews to that effect.

This seemingly easy climate solution sparked a tree-planting craze by companies and leaders eager to burnish their green credentials without actually cutting their emissions, from Shell to Donald Trump. It also provoked a squall of criticism from scientists, who argued that the Crowther study had vastly overestimated the land suitable for forest restoration and the amount of carbon it could draw down. (The study authors later corrected the paper to say tree restoration was only “one of the most effective” solutions, and could suck down at most one-third of the atmospheric carbon, with large uncertainties.)

Crowther, who says his message was misinterpreted, put out a more nuanced paper last month, which shows that preserving existing forests can have a greater climate impact than planting trees. He then brought the results to COP28 to “kill greenwashing” of the kind that his previous study seemed to encourage—that is, using unreliable evidence on the benefits of planting trees as an excuse to keep on emitting carbon.

“Killing greenwashing doesn’t mean stop investing in nature,” he says. “It means doing it right. It means distributing wealth to the Indigenous populations and farmers and communities who are living with biodiversity.”

[...]

Crowther’s November study—with more than 200 scientists listed as coauthors—instead stresses the power of preserving intact woodlands. While restoring destroyed or fragmented forests would absorb a potential 87 gigatonnes of carbon, simply allowing existing forests to grow to maturity would absorb an additional 139 gigatonnes. These estimates exclude urban, farming, and grazing areas that may once have held forests but are unlikely to be given over to nature.

573 notes

·

View notes

Text

Trees And Carbon Emissions

Great quotes from this article:

“Killing greenwashing doesn’t mean stop investing in nature,” he says. “It means doing it right. It means distributing wealth to the Indigenous populations and farmers and communities who are living with biodiversity.”

...

And even if forests are restored and preserved the right way (by avoiding sapling die-offs, wildfires, or evictions of Indigenous people), such nature projects can still contribute to greenwashing if they’re used as an excuse by businesses or governments to continue emitting carbon as usual—especially if they end up being less effective at drawing down carbon than expected.

This article has a lot more information in it, and has a built in reading of the article at the top of the page.

#punk#anarchist#anarchy#greenwashing#capitalism#indigineous people#infrastructure#carbon emissions#sustainability#trees and forests#nature#science#solarpunk

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Title: The Emergence of Everything: How Nature Leads to Life, the Life to Consciousness, the Consciousness to Spirit (Review)

Author: Marilee Crowther

Rating: ½

One of the few positively notorious hypotheses in neuroscience is the neural Darwinism theory: the idea that human brains evolved from small, non-cortical "proto-neural" structures, and that different regions of the cortex arose from different proto-neural groups.

This theory -- which has some proponents and detractors are sometimes called "neural Darwinists," and proposals for neurobiological justification of this hypothesis are often described as "neural Darwinism" or "neuro-Darwinian" (to distinguish them from sociobiological and evo-psych ideas).

In her book The Emergence of Everything ("EoE"), Marilee Crowther presents a "neuro-Darwinist" account of the emergence of consciousness from the brain. What distinguishes her account from other neuro-Darwinists is that it relies on qualitative rather than computational models of the early brain.

The main thrust of Crowther's neuro-Darwinian account of consciousness is straightforward: she sees it as a consequence of the deep similarity between the perceptual and emotional aspects of consciousness and the deep similarity between the brain and the body. An early, nonepileptic mechanism of temporal binding had evolved as a way to induce neural activity corresponding to gait, and then we learned to internalize the predictions of this model, to "stand in the shoes of the body." Neural activation associated with pain and other emotions are likewise similar to gait, and so we don't merely learn to make conceptual inferences about gait; we reenact it.

What distinguishes her account from others (to the extent that EoE is not simply an exegesis of Thomas Metzinger or Edna Victoria Hollick) is the emphasis on the importance of qualitative models. Most discussions of the "neural Darwinism" hypothesis simply posit some sort of neural capacity for adaptation or learning, without discussing the fact that each part of the brain is only roughly analogous to another part -- the visual cortex is only like the somatosensory cortex, in the same sort of way as the somatosensory cortex is like the visual cortex:

How can the visual cortex be conscious, but not the somatosensory cortex? It is a fundamental principle of the neural Darwinist model that each part of the brain ... interacts with every other part, with each having a unique view of the environment. In addition, each part is well adapted to extract whatever it is designed to extract from the sensory data. The representation of the world at any time is the result of a complex interaction of these processes. For the visual cortex this is a representation of the physical environment. For the somatosensory cortex, it is a representation of the boundaries of the body. Since the representation of the body changes as the body moves, it is hard to conceive how the somatosensory cortex could actually be conscious. But this is not really a problem of somatosensory cortex, but a problem of the entire brain.

I'm inclined to doubt that this difficulty of the somatosensory cortex is actually a problem with the somatosensory cortex and not with the idea that qualitative brain mechanisms can be fundamentally similar to top-down psychological systems. But my point here is that Crowther views the idea of neural Darwinism as demanding, not only the capability for adaptation, but the capability for adaptation in the right direction. (The idea that qualitative brain mechanisms can possess any sort of conceptual power seems suspect to me, but no matter.)

So why are qualitative mechanisms important? They're important, she says, because once the proto-neural precursors of the cerebral cortex began their neurogenesis, the proto-neural architecture was already there:

When the proto-neural precursors began their migration and they came into the forebrain with the brainstem, the precursors had already developed concepts of time. This is shown by the fact that these migrating cells were able to change their speed of migration depending on the time it took to reach a site of neuronal production.

The upshot is that, while the proto-neural precursors are qualitative, once they've become cortical, they're (a) computationally modeling qualitative mechanisms, and (b) systematically undergoing quantitative changes that make their quantitative models converge. Therefore, they are not just any old part of the brain, but a system of parts, each individually constrained by qualitative mechanisms and all systematically converging to a single (or small number of) quantitative functions. (Crowther later clarifies that the precursors themselves aren't quantitative, but just the process by which they are created, a process that produces precursors according to the laws of math and physics.)

I'm not really convinced of this idea. I have a hard time believing that various precursors would be able to produce the cortex so long as they were not quantitative; I also have a hard time believing that in a proto-neural precursor analogue of the other parts of the brain, where nothing is quantitative, we would find quantitative effects. But regardless, it isn't clear to me that even if the proto-neural precursors were quantitative, they would be sensory quantitative mechanisms.

The next step in Crowther's case for the neural Darwinianism of consciousness is more speculative still:

One can assume that the proto-neural precursors derived a sense of time because they could look at the environment and create an environment model, based on their sensory inputs. One can further assume that the environment model and the environment, such as the brain and the body, are moving in time, because one's perception is that the environment is always changing.

The early proto-neural precursors do not appear to be able to recognize that the brain and the body are moving in time. They are (she says) constrained in some way so that the early developing proto-neural precursors, before they begin their neurogenesis, are functionally different from the young adult precursors (who are further along in neurogenesis, but not yet mature):

The child has a representation of their body as a representation of their self. This would imply that they perceive the boundaries of the body are not changing in time and they are not acting in space. Thus, they can begin the process of neurogenesis.

The child and the adult are the same age, but can have drastically different perceptions of space, time and the body because the child has yet to build the neural representation of the body. In addition, the qualitative cells may be different from the child and adult.

I'm not sure I buy this idea. It seems to me that not all animals undergo neural genesis into the forebrain (certainly not during their lifetime, at least), and even if they do, it's hard to imagine that all adult animals are equally advanced in the process of neurogenesis. Crowther takes it for granted that the brain has a "self-model," which includes a representation of the body that is not moving in time, but the evidence for this is far from clear.

The major point of Crowther's book is that the brain is not just an input-processing device. The brain produces concepts, and these concepts are, as far as I can tell, largely qualitative concepts, that are not learned or derived from input, but instead "produced" or "grown" in the brain, from neurogenesis.

How does this work? The human brain begins with the precursors "creating

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nasa has extended the life of a key climate and biodiversity sensor for scanning the world’s forests which was set to be destroyed in Earth’s atmosphere.

The Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation (Gedi) mission – pronounced like Jedi in Star Wars – was launched from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida to the International Space Station (ISS) in December 2018, and has provided the first 3D map of the world’s forests.

Data from the $100m (£81m) sensor, which uses lasers to measure the structure and health of Earth’s forests, has helped scientists better understand drivers of biodiversity loss and global heating. It was going to be incinerated in the atmosphere at the start of this year. Now, after an appeal from forest experts, Nasa has changed its mind and extended the life of the mission.

It is understood that the sensor will be reinstalled and could last until the ISS is decommissioned in 2031, giving scientists more data on issues including how much carbon trees store and the effect of forest fires on the atmosphere.

Researchers overseeing the project, based at the University of Maryland, said Gedi would have the chance to finish its work and calibrate its results with other satellites due to launch this decade that will monitor the planet’s ecosystems.

“The outpouring of support we received for keeping the mission alive was incredible,” said Prof Ralph Dubayah, principal investigator on the mission. “Gedi has made over 20bn observations of the 3D structure of forests, over temperate and tropical forests. This data is helping to address longstanding issues on the role of forests in the carbon cycle – what impact has deforestation and degradation had on atmospheric CO2 concentrations?

“The mission’s return in the 2025 timeframe is spot-on for further reporting on the Paris accords. Incredibly, Gedi may well provide a decade-long set of observations of the structure and biomass of forests. From this data we can understand how natural and anthropogenic disturbances are impacting forests and their functioning.

Thomas Crowther, professor of ecology at ETH Zürich, said: “This is incredible news. Global data about the state of Earth’s ecosystems is vital for our capacity to understand climate change, and to fight against it. Losing this wealth of data would be a travesty for the global climate and biodiversity movements.”

Laura Duncanson, a research scientist on the Gedi team, said: “Extending Gedi until the end of the decade is incredibly exciting at a time when we need to understand how forests are changing in light of climate change, mass restoration efforts, shifting fire and disturbance regimes, and hopefully reduced deforestation."

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

News in Quotes

NEWS IN QUOTES

“If no one had ever said, ‘Plant a trillion trees,’ I think we’d have been in a lot better space.”

— Thomas Crowther, the former chief scientific adviser for the UN’s Trillion Trees Campaign.

Guy Who Urged Planting a Trillion Trees Begs People to Stop Planting So Many Trees

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Tree plantations are not the environmental solution they’re purported to be

https://www.wired.com/story/stop-planting-trees-thomas-crowther/

0 notes

Text

Stop Planting Trees, Says Guy Who Inspired World to Plant a Trillion Trees | WIRED

"preserving existing forests can have a greater climate impact than planting trees. "

0 notes

Text

The potential of newly created forests to draw down carbon is often overstated. They can be harmful to biodiversity. Above all, they are really damaging when used, as they often are, as avoidance offsets— “as an excuse to avoid cutting emissions,” Crowther said.

0 notes

Text

Planting Trillions of Trees Won’t Save the Planet. Here’s a Better Way - The Messenger

0 notes

Text

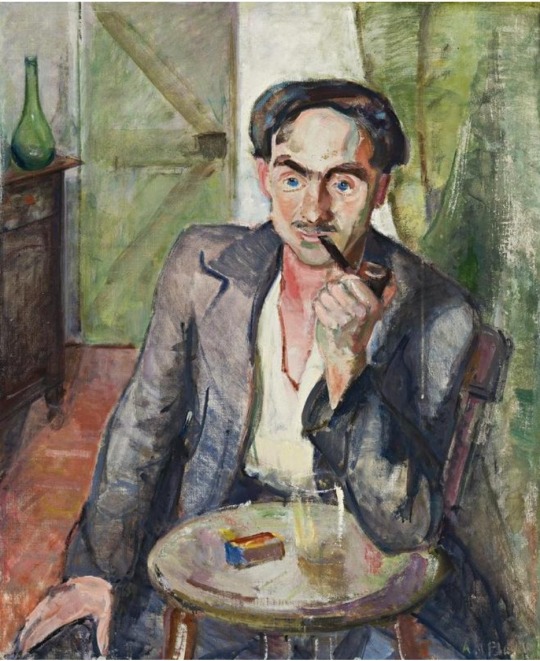

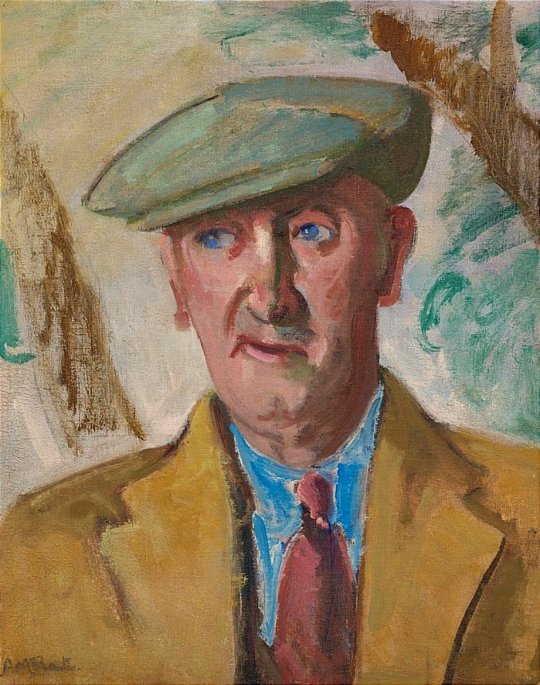

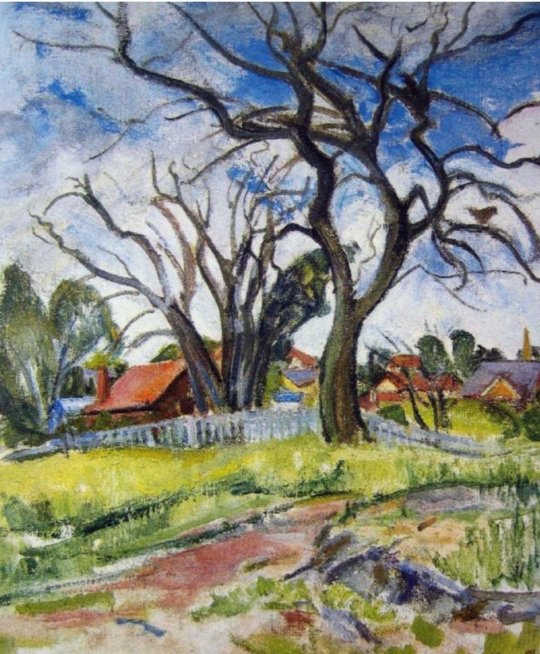

Ada May Plante (1875-1950) pintora neozelandesa.

Nació en Temuka, Nueva Zelanda. Sus padres habían emigrado de Inglaterra y su padre, Thomas Crowther Plante, trabajaba como comerciante. Su madre era Isabella Plante, de soltera Guthrie.

La familia se mudó a Australia en 1888, instalándose en East Melbourne , donde Plante se matriculó en el Presbyterian Ladies' College en 1891. Recibió formación formal en la Escuela de la Galería Nacional de Lindsay Bernard Hall y Frederick McCubbin.

Su primera exposición fue en la Victorian Artists Society en 1901.

En 1902 se trasladó a París para estudiar en la Académie Julian, compartiendo estudio con la artista australiana Cristina Asquith Baker.

Expuso su trabajo de la academia después de su regreso a Australia en la Victorian Artists Society. En 1907 expuso en la Primera Exposición Australiana de Trabajo de Mujeres, lo que le valió premios de retrato y pintura de figuras.

En 1932 expuso su obra en la primera exposición del Melbourne Contemporary Art Group. Expuso en la Sociedad de Arte Contemporáneo en 1941 y 1943 y tuvo su única exposición individual en la George's Gallery en 1945.

A lo largo de su vida vivió en casas que compartió con otros artistas, lo que le permitió entrar en contacto con muchos artistas y estar expuesta a diferentes ideas.

Si bien al comienzo de su carrera pintaba en un estilo impresionista, más tarde pudo dominar el estilo postimpresionista gracias al estímulo de artistas como William Frater y Lina Bryans, con quien vivía en una colonia de artistas en "The Pink Hotel" en Darebin.

Obtuvo elogios de la crítica de Basil Burdett por su trabajo postimpresionista.

Murió en Melbourne.

Tras su muerte se celebró una exposición conmemorativa en la Galería Stanley Coe de esa ciudad.

Le ponemos cara con su Autorretrato.

0 notes

Text

Works Cited

Please note that the following sources cannot be indented properly in Tumblr formatting.

Aristophanes. Lysistrata. Translated by Ian Johnston. First performed in 411 BCE, Nanaimo: Vancouver Island University. https://blackclassicismsp18.files.wordpress.com/2018/01/aristophanes-lysistrata.pdf.

Aristotle. Metaphysics. Translated by W.D. Ross. Documenta Catholica Omnia, -384 to -322. https://www.documentacatholicaomnia.eu/03d/-384_-322,_Aristoteles,_13_Metaphysics,_EN.pdf.

Corlett, J. Angelo. “Interpreting Plato’s Dialogues.” The Classical Quarterly 47, no. 2 (1997): 423–37. JSTOR.

Crowther, Nigel B. "Studies in Greek Athletics. Part I." The Classical World 78, no. 5 (1985): 497–558. JSTOR.

Herodotus. The Histories. Translated by George Rawlinson. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1920. https://files.romanroadsstatic.com/materials/herodotus.pdf.

Hubbard, Thomas K., ed. Homosexuality in Greece and Rome: A Sourcebook of Basic Documents. 1st ed. University of California Press, 2003.

Morgan, William, and Per Brask. “Towards a Conceptual Understanding of the Transformation from Ritual to Theatre.” Anthropologica 30, no. 2 (1988): 175–202. JSTOR.

Plato. The Republic. Translated by Benjamin Jowett. New York: Dover Publications, 2000. https://files.romanroadsstatic.com/materials/plato_republic.pdf.

Plato. The Symposium. Translated by W. Hamilton. The Penguin Classics, 1965. https://www.bard.edu/library/arendt/pdfs/Plato-Symposium.pdf.

0 notes

Text

We all knew that forest restoration could play a role in combating climate change, but we didn't really know how big the impact would be, says Prof. Thomas Crowther of ETH Zurich. Our study clearly shows that forest restoration is the best solution to climate change at the moment

Unknown

0 notes

Video

vimeo

The Singularity - Squarespace from Aoife McArdle on Vimeo.

Superbowl x Squarespace x Adam Drivers

Director: Aoife McArdle @aoifemmcardle

Production company: Smuggler @smugglersite

Executive Producers: Patrick Milling-Smith @patrickmillingsmith, Brian Carmody @bcarmo, Drew Santarsiero @ugotdrew

Managing Director: Sue Yeon Ahn @ahn_off

Head of Production: Alex Hughes

Producer: Brian Quinlan @iambq

Production Supervisors: Chad “Frenchie” Alburtis, Logan Luchsinger

Commercial Coordinators: Sydney Tracey / Julie Guez

1st AD: Anthony Dimino

Director of Photography: Khalid Mohtaseb @khalidmohtaseb

Production Designer: Kelly McGehee @itsmekellymcgee

Casting Director: Jodi Sonnenberg of Sonnenberg Casting

Stylist / Dresser: Julian Arango

CLIENT: Squarespace

Chief Creative Officer: David Lee @dmklee

VP, Creative: Ben Hughes @benhughestv

Creative Director: Mathieu Zarbatany @mathieuzarbatany

Staff Art Director: Alex Thompson @alexmichaelthompson

Staff Copywriter: Pepe Hernandez

Senior Producers: Wes Falik @wesfalik, Sion Prys

Head of Production: Erica Kung @lookupica

Staff Producer: Marisa Wasser

Head of Business Affairs: Kiersten Bergstrom-Pavlik

Senior Business Affairs Manager: Michelle Crane

Design Director: Satu Pelkonen

Design Lead: Albert Chang

Senior Designers: Ryan Carrel, Zoonzin Lee

Designer: Wan Kang

Staff Photographer: Craig Reynolds

Associate Photographer: Spencer Blake

Senior Retouchers: Sara Barr, Derek Kalisher

Editor: Sarah Harvey

Production Designer: Alex Tutelian

Motion Designers: Christina Lu, Videl Torres

Developer: Siman Li

MUSIC & SOUND DESIGN: Q Department @qdepartmentstudios

EDITORIAL:

Final Cut @finalcutedit

Managing Director: Justin Brukman

Executive Producer: Sarah Roebuck

Head of Production: Penny Ensley

Senior Producer: Jennifer Tremaglio

Editor: Dan Sherwen @dansherwen

NYC Assistant Editor: Hannah Wederquist-Keller

UK Assistant Editor: Thomas Brigden

VFX / COLOR / FINISHING:

Black Kite @blackkitestudios

VFX Supervisor: Adam Crocker

VFX Lead: Jonny Freeman, Guillaume Weiss, George Brunt

VFX Artists: Warren Gebhardt, Venu Prasath, David Birkill

3D Lead: Fin Crowther

3D Artists: Jim Cullen, Joel Paulin, Pawel Luszczak, Sandra Guarda, Florian Mounie, Ola

Madsen, Lino Khay, Ronen Tanchum, Ravikumar M.S, James Bown

Colourist: George Kyriacou

Executive Producer: Amy Richardson

Producer: Olivia Donovan

AUDIO POST:

Heard City @heardcity

Managing Partner: Gloria Pitagorsky

Sound Designer & Mixers: Mike Vitacco, Evan Mangiamele

Executive Producer: Jackie James

Senior Producers: Liana Rosenberg, B Muñoz

Producer: Nick Duvarney

Assistant Producer: Dylan Stetson

Assistant Mixers: Seth Brogdon, Virginia Wright, Zoltan Monori, Chenoa Tarin, Oddy Litlabo

1 note

·

View note

Video

vimeo

The Singularity from Aoife McArdle on Vimeo.

Superbowl x Squarespace x Adam Drivers

Director: Aoife McArdle @aoifemmcardle

Production company: Smuggler @smugglersite

Executive Producers: Patrick Milling-Smith @patrickmillingsmith, Brian Carmody @bcarmo, Drew Santarsiero @ugotdrew

Managing Director: Sue Yeon Ahn @ahn_off

Head of Production: Alex Hughes

Producer: Brian Quinlan @iambq

Production Supervisors: Chad “Frenchie” Alburtis, Logan Luchsinger

Commercial Coordinators: Sydney Tracey / Julie Guez

1st AD: Anthony Dimino

Director of Photography: Khalid Mohtaseb @khalidmohtaseb

Production Designer: Kelly McGehee @itsmekellymcgee

Casting Director: Jodi Sonnenberg of Sonnenberg Casting

Stylist / Dresser: Julian Arango

CLIENT: Squarespace

Chief Creative Officer: David Lee @dmklee

VP, Creative: Ben Hughes @benhughestv

Creative Director: Mathieu Zarbatany @mathieuzarbatany

Staff Art Director: Alex Thompson @alexmichaelthompson

Staff Copywriter: Pepe Hernandez

Senior Producers: Wes Falik @wesfalik, Sion Prys

Head of Production: Erica Kung @lookupica

Staff Producer: Marisa Wasser

Head of Business Affairs: Kiersten Bergstrom-Pavlik

Senior Business Affairs Manager: Michelle Crane

Design Director: Satu Pelkonen

Design Lead: Albert Chang

Senior Designers: Ryan Carrel, Zoonzin Lee

Designer: Wan Kang

Staff Photographer: Craig Reynolds

Associate Photographer: Spencer Blake

Senior Retouchers: Sara Barr, Derek Kalisher

Editor: Sarah Harvey

Production Designer: Alex Tutelian

Motion Designers: Christina Lu, Videl Torres

Developer: Siman Li

MUSIC & SOUND DESIGN: Q Department @qdepartmentstudios

EDITORIAL:

Final Cut @finalcutedit

Managing Director: Justin Brukman

Executive Producer: Sarah Roebuck

Head of Production: Penny Ensley

Senior Producer: Jennifer Tremaglio

Editor: Dan Sherwen @dansherwen

NYC Assistant Editor: Hannah Wederquist-Keller

UK Assistant Editor: Thomas Brigden

VFX / COLOR / FINISHING:

Black Kite @blackkitestudios

VFX Supervisor: Adam Crocker

VFX Lead: Jonny Freeman, Guillaume Weiss, George Brunt

VFX Artists: Warren Gebhardt, Venu Prasath, David Birkill

3D Lead: Fin Crowther

3D Artists: Jim Cullen, Joel Paulin, Pawel Luszczak, Sandra Guarda, Florian Mounie, Ola

Madsen, Lino Khay, Ronen Tanchum, Ravikumar M.S, James Bown

Colourist: George Kyriacou

Executive Producer: Amy Richardson

Producer: Olivia Donovan

AUDIO POST:

Heard City @heardcity

Managing Partner: Gloria Pitagorsky

Sound Designer & Mixers: Mike Vitacco, Evan Mangiamele

Executive Producer: Jackie James

Senior Producers: Liana Rosenberg, B Muñoz

Producer: Nick Duvarney

Assistant Producer: Dylan Stetson

Assistant Mixers: Seth Brogdon, Virginia Wright, Zoltan Monori, Chenoa Tarin, Oddy Litlabo

0 notes

Text

youtube

Ecologist Thomas Crowther turned one mistake into a great opportunity to fight the climate crisis.

To learn more, watch Thomas Crowther's full @TED Talk here: http://t.ted.com/pZrKCNx. For more videos like this, follow NowThis Earth.

#trees#monoculture#plantation#biodiversity#Thomas Crowther#ecologist#native trees#Solarpunk#climate crisis#global heating#Youtube

8 notes

·

View notes

Quote

After an evening kickabout, a master’s student who had worked for a tree-planting organization told Crowther that although scientists had counted trees in hundreds of thousands of spots around the globe, nobody knew how many trees there were in total. What’s more, although scientists scoffed at the usefulness to science of deriving such a number, the funders of tree restoration projects were keen to find out, to provide a quantitative basis for their work.

Satellite imagery was supplying the best estimates at the time — but satellites couldn’t tell what was going on beneath the canopy. Crowther, encouraged by Bradford, decided to look for ground data from actual tree counts “where somebody has been standing on the ground, counting the number of trees, measuring how big they are and telling us what species they are — the simplest thing ever”.

The data might be simple to collect on the ground — but persuading scientists to share their work with him seemed at first impossible.

But he gradually cajoled more scientists into complying, until eventually he had amassed data covering about 430,000 hectares — an area roughly the size of Rhode Island. With his colleague Henry Glick, a data scientist, he examined the satellite imagery for these hectares and used machine learning to make millions of comparisons between the two data sets — ground and satellite — to find repeatable correlations that would otherwise have gone unnoticed. The duo used the satellite imagery to extrapolate how many trees lived in areas that lacked good ground inventories. For example, data from forests in Canada and northern Europe were used to revise estimates of the number of trees in remote parts of Russia. This led to the first global model of tree density and the figure of three trillion trees. The team published the map in 20152.

[...] Mathew Williams, a global-change ecologist at the University of Edinburgh, says the work ignores a decade of patient work by scientists trying to work out the intricacies of tree biomass. Instead, “they’ve used a single number from each biome and they’ve just spread biomass across the biome according to the percentage canopy cover — and that’s a naive approach.” Henrik Hartmann, an ecophysiologist at the Max Planck Institute for Biogeochemistry in Jena, Germany, says that one-off climate events such as wildfires could wipe out millions of newly planted trees. “The predictions are based on what the past has looked like, but it’s no longer about mean annual temperature — it’s about having one year that is so hot and so dry that the species just won’t take it any longer,” he says.

“The ecologist who wants to map everything“ from Nature

2 notes

·

View notes