#plantation

Text

In fact, far more Asian workers moved to the Americas in the 19th century to make sugar than to build the transcontinental railroad [...]. [T]housands of Chinese migrants were recruited to work [...] on Louisiana’s sugar plantations after the Civil War. [...] Recruited and reviled as "coolies," their presence in sugar production helped justify racial exclusion after the abolition of slavery.

In places where sugar cane is grown, such as Mauritius, Fiji, Hawaii, Guyana, Trinidad and Suriname, there is usually a sizable population of Asians who can trace their ancestry to India, China, Japan, Korea, the Philippines, Indonesia and elsewhere. They are descendants of sugar plantation workers, whose migration and labor embodied the limitations and contradictions of chattel slavery’s slow death in the 19th century. [...]

---

Mass consumption of sugar in industrializing Europe and North America rested on mass production of sugar by enslaved Africans in the colonies. The whip, the market, and the law institutionalized slavery across the Americas, including in the U.S. When the Haitian Revolution erupted in 1791 and Napoleon Bonaparte’s mission to reclaim Saint-Domingue, France’s most prized colony, failed, slaveholding regimes around the world grew alarmed. In response to a series of slave rebellions in its own sugar colonies, especially in Jamaica, the British Empire formally abolished slavery in the 1830s. British emancipation included a payment of £20 million to slave owners, an immense sum of money that British taxpayers made loan payments on until 2015.

Importing indentured labor from Asia emerged as a potential way to maintain the British Empire’s sugar plantation system.

In 1838 John Gladstone, father of future prime minister William E. Gladstone, arranged for the shipment of 396 South Asian workers, bound to five years of indentured labor, to his sugar estates in British Guiana. The experiment with “Gladstone coolies,” as those workers came to be known, inaugurated [...] “a new system of [...] [indentured servitude],” which would endure for nearly a century. [...]

---

Bonaparte [...] agreed to sell France's claims [...] to the U.S. [...] in 1803, in [...] the Louisiana Purchase. Plantation owners who escaped Saint-Domingue [Haiti] with their enslaved workers helped establish a booming sugar industry in southern Louisiana. On huge plantations surrounding New Orleans, home of the largest slave market in the antebellum South, sugar production took off in the first half of the 19th century. By 1853, Louisiana was producing nearly 25% of all exportable sugar in the world. [...] On the eve of the Civil War, Louisiana’s sugar industry was valued at US$200 million. More than half of that figure represented the valuation of the ownership of human beings – Black people who did the backbreaking labor [...]. By the war’s end, approximately $193 million of the sugar industry’s prewar value had vanished.

Desperate to regain power and authority after the war, Louisiana’s wealthiest planters studied and learned from their Caribbean counterparts. They, too, looked to Asian workers for their salvation, fantasizing that so-called “coolies” [...].

Thousands of Chinese workers landed in Louisiana between 1866 and 1870, recruited from the Caribbean, China and California. Bound to multiyear contracts, they symbolized Louisiana planters’ racial hope [...].

To great fanfare, Louisiana’s wealthiest planters spent thousands of dollars to recruit gangs of Chinese workers. When 140 Chinese laborers arrived on Millaudon plantation near New Orleans on July 4, 1870, at a cost of about $10,000 in recruitment fees, the New Orleans Times reported that they were “young, athletic, intelligent, sober and cleanly” and superior to “the vast majority of our African population.” [...] But [...] [w]hen they heard that other workers earned more, they demanded the same. When planters refused, they ran away. The Chinese recruits, the Planters’ Banner observed in 1871, were “fond of changing about, run away worse than [Black people], and … leave as soon as anybody offers them higher wages.”

When Congress debated excluding the Chinese from the United States in 1882, Rep. Horace F. Page of California argued that the United States could not allow the entry of “millions of cooly slaves and serfs.” That racial reasoning would justify a long series of anti-Asian laws and policies on immigration and naturalization for nearly a century.

---

All text above by: Moon-Ho Jung. "Making sugar, making 'coolies': Chinese laborers toiled alongside Black workers on 19th-century Louisiana plantations". The Conversation. 13 January 2022. [All bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me.]

441 notes

·

View notes

Photo

” Behold the fingerprint of the land,” Guizhou, China.

Nestled in the rolling hills of Guizhou, a remarkable tea plantation bears witness to the astounding beauty of nature's patterns.

Photo by: @youknowcyc

#art#landscaping#agriculture#china#guizhou#plantation#earth#nature#green#drone photography#tea#hills#zen#retreat#landscape architecture

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

witch’s treehouse

Buy me a Coffee // My Links // Merch

#pixelart#witch#witchy vibes#cottage#cottagecore#tree#treehouse#nature#moss#overgrown#mushrooms#shack#abanedoned#night#fireflies#plantation#my art

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Haircutting in Front of General Store and Post Office on Marcella Plantation, Mileston, Mississippi, Marion Post Wolcott, 1939

#photography#vintage photography#vintage#black and white photography#american#marion post wolcott#mississippi#mileston#plantation#1930s#1939#female artists#women artists#photojournalism

113 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The World of Sugar: How the Sweet Stuff Transformed Our Politics, Health, and Environment over 2,000 Years

While granulated sugar was produced in India as early as the 6th century BCE, its usage for a long time remained limited to royalty or ceremonial purposes. It was not until the 13th century that sugar became a major commercial product throughout Eurasia. India, China, Persia, and Egypt were significant in this transformation, prompting Bosma to state that “sugar capitalism began in Asia.”

Continue reading...

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cut-away forest.

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

Your daily brew has a remarkable past! From its legendary origins in Ethiopia to its influential contributions to the Age of Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution, coffee's rich history shaped nations and fueled revolutions.

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hampton National Historic Site, Maryland

photo: David Castenson

#black and white photography#hampton national historic site#landscape#plantation#photographers on tumblr

205 notes

·

View notes

Text

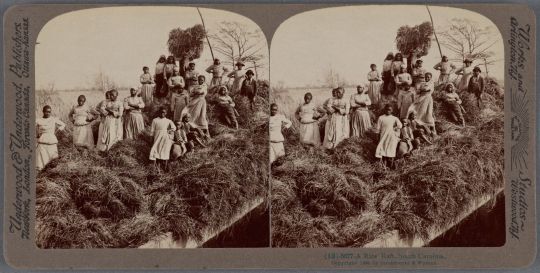

A stereoscope of plantation workers -- seemingly women and children -- riding on a rice raft in South Carolina, 1895. These workers would have been bringing straw from the rice plants to feed livestock after harvesting the more valuable rice grains.

{WHF} {Ko-Fi} {Medium}

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

As a SIDENOTE to the previous post, there is a historical plantation site in Texas, the Varner-Hogg Plantation, south of Houston, where they have removed any books about slavery from the museum giftshop. And the Texas Historical Commission has been sanitizing the video and mentions of slavery in the tour media.

Cause apparently if you send enough mean emails, and you are White, the THC will change history to accommodate you.

Cause the way you right the wrong of history is to hide it so that Whitey doesn't feel uncomfortable.

link

#BulldozeThePlantation

SIDENOTE TO THE SIDENOTE: Among the books removed are "an autobiography of a slave girl, a book of Texas slave narratives, the celebrated novel Roots by Alex Haley, and the National Book Award–winning Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison."

#don't trust whitey#history#slavery#texas#plantation#books#library#bookstore#reading#reading is fundamental

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

On the night of April 30, 1541, the Ming Ancestral Temple in Beijing was struck by lightning and burned to the ground. [...]

[T]he fires forced the Jiajing Emperor to resurrect one of the dynasty’s most expensive, difficult, and destructive projects: the logging of old-growth timber in the far southwest of China. Disaster struck again in 1556, when fires burned the Three Halls that form the central axis of the Forbidden City. The Three Halls burned yet again in 1584. Through the end of the sixteenth century, repeated damage to the imperial palaces forced reconstruction. Yet the lightning strikes in Beijing were also a disaster for the old-growth forests of the southwest, where the logs to build the palaces had first been cut in the early 1400s. As logging supervisors soon learned, ancient trees could not be felled on a regular basis. Officials pressed ever deeper into the gorges of southern Sichuan and northern Guizhou to find them, bringing massive transformations to the environment in the process.

---

The foundations of Beijing were laid between 1406 and 1421 by the Yongle emperor, a junior son of the Ming founder, who moved the court to his personal appanage in north China. [...] Grasping the sinews of power that connected his court to far-flung regions of the empire, Yongle pulled one million laborers to Beijing to build his palaces.

Because the weight of Chinese buildings is carried by their pillar-and-beam frameworks (liangzhu), monumental buildings required monumental trees (Figure 2). So Yongle also dispatched a similarly large labor force to the old-growth forests of the far southwest to cut the fir (Cunninghamia lanceolata) and nanmu (Phoebe zhennan) that grew straight and tall enough to be used for imperial construction.

We cannot be certain just how many logs were cut to build Beijing, but the figure must have been astounding. In 1441, two decades after the completion of the project, 380,000 large timbers were left over from the earlier construction. By 1500, these too were gone, used for repairs or too damaged by rot to be used for construction purposes.

---

In the sixteenth century, logging officials wondered how their predecessors had been able to obtain so many giant timbers. Li Xianqing, who supervised more than 40 logging sites in the 1540s, noted that large trees could still be found, but they could only be transported out with great difficulty and at great expense. The majority had to be discarded as hollow or insect-damaged.

Even when a quality log was found, it took five hundred workers to tow a log over mountain passes.

Skilled craftsmen were on hand to build “flying bridges” (fei qiao), stone-lined slip roads, and enormous capstans (tianche) to tow the logs up slopes (Figures 3 and 4). In the remote forests of the southwest, loggers faced attacks by snakes, tigers, and “barbarians” (manyi); “miasmatic vapors” (yanzhang, probably malaria); storms, forest fires, rockslides, and raging rivers (Figure 5). Labor teams had to carry their own food and often starved. At the rivers, logs were tied into massive rafts bound with bamboo for buoyancy, towed by teams of 40 men, and then launched on the three-year, three-thousand-kilometer journey to Beijing (Figure 6). Only a small fraction of the trees reached the capital in a condition where they could be used for palace building.

---

Expeditions exceeded their budgets up to fiftyfold.

One official remarked, “the labor force numbers in the thousands; the days number in the hundreds; the supply costs number in the tens of thousands each year.” Another saying held that “one thousand enter the mountains, but only five hundred leave” (rushan yiqian chu shan wubai). To make matters worse, logging mostly occurred within territory that was under only loose Ming control [...].

---

The Yongle Palaces were said to replicate the otherworldly atmosphere of the old-growth forests where their pillars originated. The presence of these timbers in Beijing linked the capital, materially and symbolically, to the southwestern landscape of cliffs and gorges where the trees had grown.

But ancient sentinel trees could not be reproduced on demand. The fifteenth-century logging project was a millennial event, removing the growth of hundreds or even thousands of years. Later officials were forced to come to terms with the transformations their predecessors had wrought in the ancient forests. Eventually builders had to switch to smaller, commercially available timber, using ornate artisanship and commercial efficiency to substitute for the austere majesty of the early Ming palaces, and the thousands of years of tree growth on which they rested.

---

All text above by: Ian M. Miller. “The Distant Roots of Beijing’s Palaces.” Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society, Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia no. 39. Autumn 2020. [Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me.]

408 notes

·

View notes

Text

Federal Agency Rejects Developer’s Report That Massive Grain Elevator Won’t Harm Black Heritage Sites

For the second time in six months, a federal agency reprimanded a Louisiana developer for failing to adequately assess the harm that its proposed $400 million agricultural development would cause to neighboring Black communities and historic sites.

In a forceful letter dated Dec. 23, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers rejected claims by the developer, Greenfield LLC, that its massive grain transfer facility in St. John the Baptist Parish upriver from New Orleans will have “no adverse effects.” The Corps is considering a permit application by Greenfield to build on federally protected waters and has the power to halt the project.

That new report, which the Corps received in November, did not address the agency’s demand that the developer conducts a more complete assessment of how the project could damage historic sites and harm residents of nearby towns, according to the Corps’ December letter.

“The report,” the letter reads, “just doesn’t demonstrate adequate engagement, and that must be rectified.”

A Greenfield spokesperson said our team of respected expert consultants and have done thorough evaluations to consider any and all potential impacts. The statement said Greenfield takes seriously its responsibility to provide regulatory agencies with accurate and complete information consistent with the regulatory requirements.

The Corps’ letter criticizes Greenfield and its contractors for failing to meaningfully consult with people whose lives would be impacted by the dozens of looming grain silos, new rail, truck, and shipping traffic, and pollutants from the facility. It says Greenfield and its consultants have not done enough to account for how the development project might harm communities of color, a requirement under federal environmental justice standards.

“It’s very disappointing that they would continue to double down on the report, that they are still saying there will not be any detrimental effects,” Erin Edwards, who blew the whistle on the earlier report, told ProPublica in a recent interview.

“It’s very disappointing that they would continue to double down on the report, that they are still saying there will not be any detrimental effects,” Erin Edwards, who blew the whistle on the earlier report, told ProPublica in a recent interview. Edwards co-authored the first version of the information when she worked as an architectural historian for Gulf South Research Corporation, the for-profit cultural resources, and archaeological consulting firm hired by another of Greenfield’s consultants to conduct a federally required assessment of historical sites.

Edwards resigned in late 2021 after her report was stripped of every mention of possible harm to communities or cultural properties, including her conclusion that the area surrounding the development should be listed as a historic district because of its connection to histories of slavery. In internal Gulf South emails obtained by ProPublica, a company manager wrote that it would lose its contract for the report — and could lose future work — if it didn't change the findings.

“Gulf South knew all along that the project would harm the historic plantations there, and they knew that it would hurt the area as a whole,” Edwards said. “There’s no way to look at the evidence and not see that it’s going to be detrimental.”

The Greenfield grain facility has been the target of sustained pushback from nearby communities, civil and human rights groups, and historic preservation organizations, as well as from other federal agencies, including the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, which oversees national preservation policy. The land where the development is planned sits beside the Whitney Plantation Museum, which serves as a memorial to enslaved people in Louisiana. One plot of land down the river is another unusually well preserved plantation designated as a National Historic Landmark.

To read the ProPublica Report, you can find the complete publication by clicking here and going directly to the information by visiting their site.

#black pride#black history#black lives matter#blacklivesmatter#black stories#black life#black history month#black history matters#civil rights#civil rights movement#race and politics#critical race studies#slavery#slave trade#slave owner#naacp#aclu#southern poverty law center#plantation#polution#grainhandling#grain drying#historical sites#communities of color#black families#new orleans#louisianna#historic sites#gulf south#advisory council

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

His grandmother gave him the nickname "Muddy" at an early age because he loved to play in the muddy water of nearby Deer Creek. Muddy grew up in the cotton country of the Mississippi Delta on the Stovall plantation near Clarksdale, Mississippi. He taught himself to play harmonica and played guitar simply, yet powerfully, proving that three chords played rhythmically and loudly could be as expressive as any tune with more notes and chords. "Waters" was added years later, as he began to play harmonica and perform locally in his early teens.

He had his first introduction to music in church and by the time he was 17 he had purchased his first guitar. "I sold the last horse that we had. Made about fifteen dollars for him, gave my grandmother seven dollars and fifty cents, I kept seven-fifty and paid about two-fifty for that guitar. It was a Stella and people ordered them from Sears-Roebuck in Chicago."

As a young man, he drove a tractor on the sharecropped plantation, and on weekends he operated the cabin in which he lived as a “juke house,” where visitors could party and drink moonshine whiskey made by himself. He eagerly absorbed the classic Delta blues styles of Robert Johnson, Son House, and others while developing a style of his own.

Muddy Waters was born McKinley Morganfield and died on April 30, 1983 at the age of 70.

#muddy waters#love#music legend#delta blues#chicago blues#musician#guitars#harmonica#great migration#black lives#chicago#mississippi#sharecropper#plantation#sears roebuck

46 notes

·

View notes

Note

Question. Didn’t Lestat have money in the first book? Cuz anne made him seem a bit poor in the first book

Louis said he didn’t. But then... Louis didn’t leave one good hair on Lestat….

He appeared frail and stupid to me, a man made of dried twigs with a thin, carping voice.

For example. 😅

I think Louis more or less surmised it at the beginning, because Lestat took the money from their victims, and because he started to furnish the plantation:

‘That’s mortal nonsense,’ he would say to me, while at the same time spending so much of my money to splendidly furnish Pointe du Lac, that even I, who cared nothing for the money, was forced to wince.

Louis takes it upon himself to invest their money, and grow their capital. He thinks he keeps Lestat dependent on him:

For all these years, I’d kept him dependent on me. Of course, he demanded his funds from me as if I were merely his banker, and thanked me with the most acrimonious words at his command; but he loathed his dependence.

(Note the tone implied when Lestat thanks him for money.)

Which is, like, very far from the truth, actually. And it is psychologically very interesting, indeed, especially for the show to hook into imho, but that just as a side note.

This very hard, harsh depiction of Lestat lasts into the second half of the book and then the longing breaks through, obviously impossible to contain:

A sickness rose in me more wretched than anguish when I saw what my dreams were doing. I wanted him alive! In the dark nights of eastern Europe, Lestat was the only vampire I’d found.

I allowed myself to forget how totally I had fallen in love with Lestat’s iridescent eyes, that I’d sold my soul for a many-colored and luminescent thing, thinking that a highly reflective surface conveyed the power to walk on water.

“What would Christ need have done to make me follow Him like Matthew or Peter? Dress well, to begin with. And have a luxurious head of pampered yellow hair.

But that just as a reminder that Louis changes his own stance on certain things even within the story...

Now for the money itself.

In regards to Lestat and money / status Anne set down some interesting basics already, very early in the book - because when Lestat cares still for his father this is a scene:

Don’t I take care of you in baronial splendor!’ Lestat would shout at him.

Don’t I provide for your every want! Stop whining to me about going to church or old friends! Such nonsense. Your old friends are dead. Why don’t you die and leave me and my bankroll in peace!’

There's two very interesting hints in there. For one we know that Lestat was the son of a Maquis, so that man is the Maquis. The "barionial splendor" is a direct hint to their previous lifestyle and the fact that Lestat took care of his father (and his family) then, too.

And then, of course, there's "leave me and my bankroll in peace". This quote is from a part very early in the book. Which makes it clear Lestat did have money at his disposal.

How much exactly is not said, but as said before Louis thinks Lestat is after his plantation because... honestly, he cannot, for a long time, fathom why Lestat would be after him. He cannot understand that Lestat fell in love with him immediately. He cannot believe that Lestat loves him, like that, and has gone full in.

That just doesn't compute for Louis... for a long, long time.

Arguably, I think that is the same in the show.

And, I've said it before, that is a very scary concept, too, so I can understand why Louis had such a hard time accepting.

Someone as beautiful, powerful, capricious, difficult and vivacious as Lestat being totally gone on you... yeah. That is a scary concept.

#asks#money#baronial splendor#bankroll#plantation#amc iwtv#iwtv#amc interview with the vampire#interview with the vampire amc#iwtv amc#iwtv 2022#interview with the vampire#lestat de lioncourt#louis de pointe du lac#loustat#iwtv meta#vc meta#interview with the vampire meta#book quotes#ask nalyra

24 notes

·

View notes