#The Makioka Sisters

Text

The Makioka Sisters by Jun'ichirō Tanizaki, translated by Edward G. Seidensticker, can be a bit of a slog. At 562 pages, this book tells the story of four sisters of an old, noble Osaka family. The main plot is Austen-esque: trying to get the 3rd sister, quiet Yukiko, married despite the high, almost snobbish standards of the old Makioka family, so that poor, modern, outgoing Taeko (affectionately called "Koi-san") can marry her long-time lover. As marriage negotiations continue to fall through for Yukiko, Taeko gets increasingly impatient, and older sister Sachiko worries that her behavior will bring ruin to the family name.

I first, fittingly, began reading this book on the train from Osaka to Tokyo. It was covered by a flowery book cover I bought from a children's library on Nakanoshima island. Despite my best efforts, it took me more than a weekend to get through the hefty paperback.

Making Sachiko our central protagonist gives us an unreliable narrator in an intriguing way: her sensitive, traditional mindset leaves the reader both nostalgic and frustrated in turns. The book's biggest weakness was long, hefty paragraphs that could be repetitive from other sections. I suspect this comes from it being serialized and published in parts. I think the book would have benefited from multiple point-of-views. Sachiko is the perfect representative of the old family, but her actions were often snobbish and cold, and it would have been interesting to have her unreliability interrogated by having Taeko's point of view as well, here and there.

Its biggest strength is to be read between the lines. Over the events of this book, which seem so couched in dated tradition and formality, loom hints of austerity measures and rumors that mark the impending shoe drop of Japan entering World War II. There's a sense (reinforced by the book's Japanese title, "lightly falling snow," which can refer to the falling cherry blossoms, a season of beauty short-lived and always destined to end each year) of impermanence around the entire book. This is a way of life about to be obliterated by world events.

It's worth noting that the government actually stopped the publication of this book in 1943 because “The novel goes on and on detailing the very thing we are most supposed to be on our guard against during this period of wartime emergency: the soft, effeminate, and grossly individualistic lives of women.” All of this gives the novel a very specific wash as a frozen moment in time destined to be swept away. Its ending carries a sort of sadness to it: without spoilers, Sachiko feels confident that the future is set, but World War II is about to change everything for her family and country.

Even in the book itself, many holidays, festivals, and traditional arts and celebrations are being reeled back in light of the Second Sino-Japanese War. All of the book's readers during and after World War II would have recognized this acutely, and I suspect that feeling of loss and nostalgia for a traditional Japan (in all its good and bad) was a huge contributor to making this book a classic.

As for the ending, the book's pacing was steady throughout, less like a flight (with a take-off, stabilization, and descent) and more like a train ride, straight across with a few interesting stops. The ending felt like getting off one stop before the train's final destination. Unceremonious, and it feels like the story keeps going straight ahead, but you're hurried off the train anyway. The events of the last three pages were large compared to a lot of others in the book that got entire chapters, and yet Tanizaki breezes over them and leaves us, it almost feels, mid-paragraph. I did like the bittersweetness he tries to leave us with, but the final sentence felt very low-energy for being the final words of a 500+ page book.

Content warnings for misogyny, ableism, classism, mental illness.

#the makioka sisters#jun'ichirō tanizaki#japanese literature#books in translation#classics#global literature#world classics#historical fiction#my book reviews#reading while wandering japan

39 notes

·

View notes

Note

In your poll I voted for queer-coded Yukiko with more hope in my heart than certainty, realising I was going to have to reread "Sasameyuki" to hunt for clues. >.> At length, I did. Lesbian Yukiko, I just don't see in the text (though if you do, I'd love to hear more). Ace Yukiko feels plausible — but then, asexuality is outwardly indistinguishable from being a Nice Girl from a Good Family, so I'm not rushing to judgment there. But may I posit Autistic Yukiko—? Fastidious about her food, socially maladroit and so shy around strangers that she can barely speak, stubbornly attached to her same place, her same people, her same clothes (i.e. she's still wearing the kimono of her youth), content to let the rest of life pass her by while she continues year after year in her familiar routines — and, as much as possible, avoids the telephone. *sympathetic shudder*

I'm bogged down in the middle of a reread myself right now (I've read Sasameyuki in a few weeks to a month; I've read Sasameyuki in a few days; this time I'm taking over a year) and I remember a lot of what I read as the lesbian-ish coding coming later on in the novel, so I'll have to get back to you on that. Aro-ace Yukiko is a totally solid read too; I believe it's the sense that @carys-the-ninth got when she read it.

Having said that, YES YUKIKO IS AUTISTIC. You see her! You understand her! The phone scene is a great example (just as it's so key to understanding her in general), but I think it shows up even in otherwise difficult-to-explain moments like her apparently thinking it's better for Taeko to marry Okubata than to marry Itakura, from a standpoint of genuine concern for Taeko's wellbeing. That's what the (metaphorical) social skills book said would constitute a good life outcome for Taeko. Why won't Taeko defer to the social skills book??

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

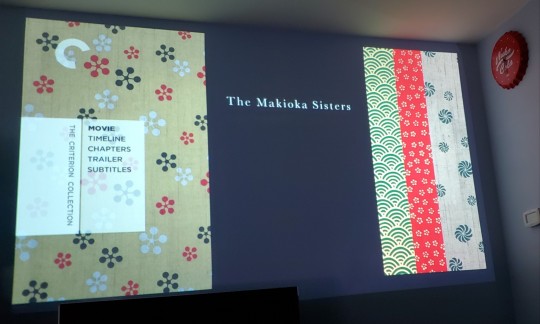

#The Makioka Sisters#Ichikawa Kon#Criterion Collection#Never had an opportunity to use the projector for films before#But now we've got a stand alone blu-ray player because my wife is brilliant!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

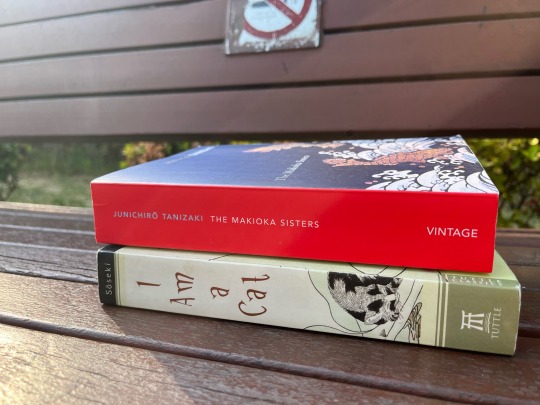

This Week's Books are...

The Makioka Sisters by Tanizaki Junichiro and I Am a Cat by Natsume Soseki!

Yay, more rereads! I read The Makioka Sisters back in January or February, so it's only obivous that I had to revisit it. My sister loves two authors, Maupassant and Soseki; and that's why i'll be rereading I Am a Cat this week :)

I actually bought these books secondhand, which leads me to ask, how do you all feel abt secondhand books? love em or hate em?

Also, another Mishima work will be coming in the mail soon!!! yay!!!

#literature#books#classical literature#reading#japanese literature#studying#book blog#books & libraries#hyeji reads 📚#writing#aesthetic#book recommendations#natsume soseki#i am a cat#tanizaki junichirou#the makioka sisters

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

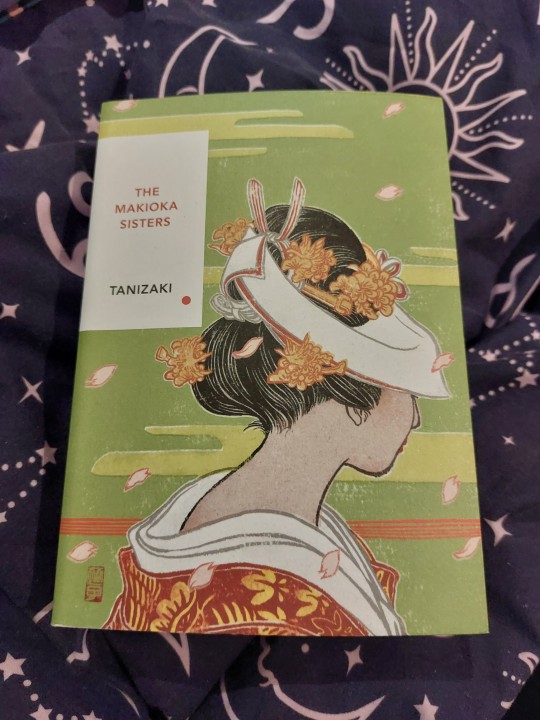

Finally finished this last week. Tbh I wasn't that impressed with it, sorry Tanizaki.

0 notes

Photo

Yoshiko Sakuma, Sayuri Yoshinaga, Yûko Kotegawa, and Keiko Kishi in The Makioka Sisters (Kon Ichikawa, 1983)

Cast: Yoshiko Sakuma, Sayuri Yoshinaga, Yûko Kotegawa, Juzo Itami, Keiko Kishi, Yonedanji Katsura. Screenplay: Shin’ya Hidaka, Kon Ichikawa, based on a novel by Jun’ichiro Tanizaki. Cinematography: Kiyoshi Hasegawa. Production design: Shinobu Muraki. Film editing: Chizuko Osada. Music: Shinnosuke Osawa, Toshiyuki Watanabe.

Lovers of romantic historical costume dramas like the Merchant Ivory movies and the flood of Jane Austen adaptations will find much that's familiar in Kon Ichikawa's The Makioka Sisters. The lushly melancholy scene at the beginning of the film, in which the sisters walk through the blossoming cherry orchards in Kyoto, accompanied by an instrumental arrangement of Handel's aria "Ombra mai fu" from Serse, anticipates by two years the scenes in Tuscany in the Merchant Ivory version of E.M. Forster's A Room With a View (James Ivory, 1985) that are set to music like Puccini's "O mio babbino caro" and "Chi il bel sogno di Doretta." The plot consists of finding a husband for one of the sisters, Yukiko (Sayuri Yoshinaga), whose marital prospects are endangered by the unconventional behavior of her younger sister, Taeko (Yuko Kotegawa), just as Jane and Elizabeth Bennet's were by the scandalous behavior of their sister, Lydia, in Pride and Prejudice. And just as Austen's novels took place against the distant background of the Napoleonic wars, so do the Japanese military incursions into China -- the film begins in the spring of 1938 -- recede into the background of the domestic problems of the Makioka sisters. There are four Makioka sisters, the proud remnants of a family whose male line has died out, but the husbands of the two oldest sisters, Tsuruko (Keiko Kishi) and Sachiko (Yoshiko Sakuma), have adopted the family name and are helping rebuild its fortunes. The sisters adhere to the family tradition that older sisters must marry before younger, which Taeko, the youngest, rebels against. As the film begins, she has already tried to elope with the irresponsible Okuhata (Yonedanji Katsura), and although the family thwarted that attempt, the story made it into the newspapers, which incorrectly reported Yukiko as the one who tried to elope. The family demands a retraction, but the newspaper only issues a correction. Yukiko is beautiful but shy, and attempts by a matchmaker to arrange a marriage for her have fallen through. There is a wonderful scene in which the family goes to meet a suitor, who turns out to be a terrible but funny bore. Ichikawa, who co-wrote the screenplay with Shinya Hidaka, develops and individualizes the characters of the sisters and their husbands well, and stays just this side of romantic sentimentality. The cinematography by Kiyoshi Hasegawa makes the most of the colorful settings -- spring cherry blossoms and autumn foliage -- and especially the beautiful costumes of Keiko Harada and Ikuko Murakami. Only occasionally does the note intrude that this is an ephemeral world, soon to be swept away by war.

0 notes

Text

rip in peace to The Earth Is Online but i must drop it because i'm too much of a literature snob to read 240+ machine translated chapters

#i say this light-heartedly because i shan't be picky with free fan translations of silly action-adventure novels online#but 30 chapters in and i'm still not particularly interested in this story#the premise is good and i had high expectations for it bc of the recs from other orv enjoyers#but it's just meh. like the translation is mid but even the storytelling isn't gripping enough to be worth it#there's better things to read i guess :(#but what do i now read instead. since this one was on my list for so long aough#(and rip to all the high literature i said i would read. like the makioka sisters... i WILL!! but later. i'm too lazy rn oops)

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

how fast do u guys think imgonna finish reading naomi

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Admiring Osaka roses while reading the Jane Austen–like tales of the Makioka sisters.

#the makioka sisters#Jun'ichirō Tanizaki#japanese literature#japan books#japan travel#reading while wandering japan

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

why didn't anyone tell me that tanizaki's makioka sisters is a huge book 💀 I bought it in english (not my first language) because I tought I would be able to read it without any problems.

I read crime and punishment in my first language because I tought I would struggle too much if i read it in english...

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

"In Osaka in the years immediately before World War II, four aristocratic women try to preserve a way of life that is vanishing. As told by Junichiro Tanizaki, the story of the Makioka sisters forms what is arguably the greatest Japanese novel of the twentieth century, a poignant yet unsparing portrait of a family–and an entire society–sliding into the abyss of modernity.

Tsuruko, the eldest sister, clings obstinately to the prestige of her family name even as her husband prepares to move their household to Tokyo, where that name means nothing. Sachiko compromises valiantly to secure the future of her younger sisters. The unmarried Yukiko is a hostage to her family’s exacting standards, while the spirited Taeko rebels by flinging herself into scandalous romantic alliances. Filled with vignettes of upper-class Japanese life and capturing both the decorum and the heartache of its protagonist, The Makioka Sisters is a classic of international literature."

1 note

·

View note

Text

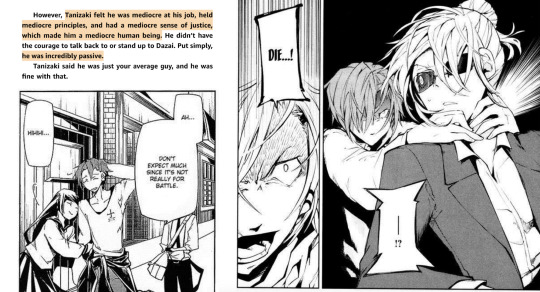

Fucking HELL the BSD writers are on another level of clever. Just found out that the main character of the book No Longer Human attempts a double suicide with a woman by method of drowning, but was saved. Dude the way his ability isn't just named after the story- his CHARACTER references the PLOT!! Of the book the REAL DAZAI WROTE!!! The way in Bungo Preschool all of the kids are requesting books that their namesakes wrote, like Tanizaki asking to be read The Makioka Sisters, a book by the actual Junichirou Tanizaki. There's probably so many literature easter eggs I'll never be aware but the effort they put into it is soooooo cool

#kennacanthink#bungou stray dogs#bsd#dazai osamu#tanizaki junichirou#it's so cool learning about No Longer Human and suddenly going OHHHHOLY SHIT THAT'S WHY HE WANTED A DOUBLE SUICIDEEEEEEE#IT'S IN THE FUCKING BOOK

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

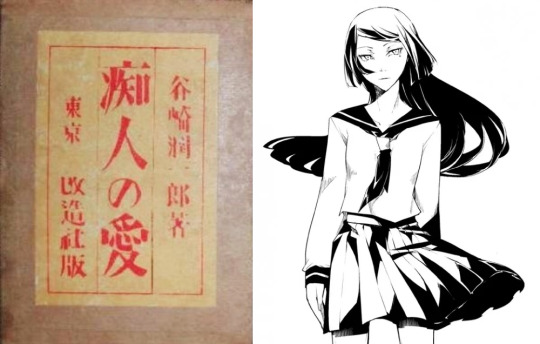

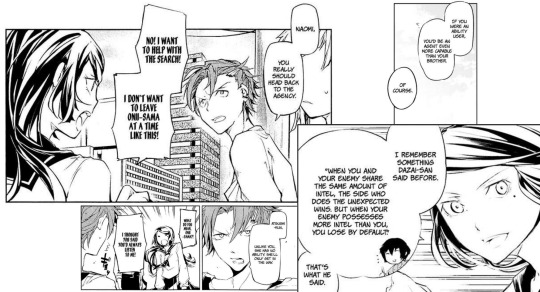

Analysis of BSD Tanizaki (Character and Theories) in Reference to Real Life Tanizaki Jun’ichirou

By popular demand of (1) person in the comments of a post I’ve made briefly touching on this subject, I have compiled all of my thoughts on the portrayal of Tanizaki Jun’ichirou—and by extension, Naomi—in Bungou Stray Dogs in reference to the works of the real life Tanizaki Jun’ichirou-sensei (who I’ll be calling Tanizaki-sensei to differentiate from his fictional counterpart). Disclaimer that I don’t have the academic background to write as an expert on this subject. I will be citing all of my sources in the text.

Tanizaki-sensei (1886-1965) was an author who was well known for writing about sexual obsession and fetishes, and the exploration of Japanese versus Western culture in his works. His female characters were particularly reputable for having strong personalities (drawing upon the dofuku - “poisonous woman” or femme fatale troupe), and frequently fulfilled the domineering role in sadomasochistic relationships with men. This recurring theme is most likely the basis for Tanizaki and Naomi’s relationship in Bungou Stray Dogs.

In a similar vein, motifs such as dreaming, delusions, and fantasies (oftentimes of the erotic nature) frequently appear in Tanizaki-sensei’s works. This could be the basis for Tanizaki’s illusion projection ability, “Light Snow”, which is named after Tanizaki-sensei’s great novel, Sasameyuki (1948), also known as The Makioka Sisters, the title of the English translation, which was changed due to the nuance of the original title being difficult to convey in English.

Going on a slight tangent here, Tanizaki-sensei also wrote a handful of works depicting blindness, such as A Portrait of Shunkin (1933) and A Blind Man’s Tale (1931). In these works, blindness can be interpreted as a metaphor for blind devotion and obsessive worship of one’s love interest, even to the point of martyrdom. For example, in A Portrait of Shunkin (1933), the character Sasuke destroys his own eyesight for his vain mistress, who did not want to be seen after an incident destroys her beauty. Tanizaki and Naomi’s deep affection for each other is reminiscent of these themes (Tanizaki’s willingness to throw away his morals for Naomi, Naomi taking gunfire in Tanizaki’s place).

Unfortunately, we aren’t given any other concrete pieces of information about Tanizaki or Naomi that can be reliably connected to something in regards to the real life author...

The Unreliable Narrator

Which brings me to my first point in regards to fan theories surrounding Tanizaki and Naomi. I have mentioned in previous posts that Tanizaki’s descriptions of himself oftentimes contradict what we are actually shown (not good for combat, cowardly and average, etc), which means that Tanizaki is an unreliable narrator of his own backstory. To what extent he is unreliable, we can only speculate.

However, the theory that Tanizaki cannot be trusted to tell the truth about himself is supported by the real life counterparts’ use of this narrative device in his works. A journal article by The Columbia Companion to Modern East Asian Literature explains that “[Tanizaki-sensei’s stories] are often told by a personified and thus not necessarily reliable narrator,” which is especially evident in both Naomi (1925), a post-hoc account of the protagonist’s marriage, and The Key (1956), two juxtaposed diaries of a married couple.

Since Tanizaki-sensei tended to employ biased narrators in his stories, Tanizaki being an unreliable narrator of his own story would be a clever nod to his real life counterpart.

Moving on, the theory that Tanizaki may be lying about himself opens a world of possibilities regarding what the truth actually is. One popular fan theory is that Naomi is actually an illusory ability construct created by Tanizaki’s ability “Light Snow”.

Sculpting the Ideal Woman

Another recurring theme in Tanizaki-sensei’s works is a character’s desire to “shape” a woman into their vision for what that woman should be. This takes a variety of forms: in The Tattooer (1910), the protagonist “[desires] to create a masterpiece on the skin of a beautiful woman”, thus transforming her into a “real beauty”. In Aguri (1922) the protagonist dreams that “he would adorn [her] with jewels and silks. He would strip off that shapeless, unbecoming kimono... and then dress her in Western clothes”. The desire to make a woman more “Western” is also apparent with the protagonist Joji’s intent in Naomi (1925), the book that BSD Naomi is named after.

However, I must caution that BSD Naomi is actually quite different from how the character of Naomi is in the original novel; BSD Naomi is kinder to the people around her, and isn’t portrayed as selfish or manipulative. The two Naomis’ do share their penchant for mischief, and their bold, tomboyish personalities, as well as their surprising intelligence and aptitude for planning.

Back to the main topic: other BSD fans have pointed out that this theme of “making Naomi” in the novel supports the theory that BSD Naomi was created by Tanizaki’s ability. Considering that this pygmalion-like desire also appears in many other stories written by Tanizaki-sensei, the connection makes sense. Notably a role reversal between the “sculptor” and the “sculpture” always takes place in such stories.

Losing Control

In Tanizaki-sensei’s stories, female characters who are transformed to fit a man’s ideal are rarely subservient by the end of the narrative. Instead, the change oftentimes pushes them into a more dominant role, where they are the ones doing the controlling, rather than being controlled. In Naomi (1925), the protagonist narrates that “I forgot my innocent notion of "training" her: I was the one being dragged along, and by the time I realized what was happening, there was nothing I could do about it.” As the alternate title, A Fool’s Love, may suggest, by the end of the book Naomi has made a fool out of the protagonist, having “made careful plans and lured [him] on”, ultimately ending up in a position of power.

This could be indicative of Naomi’s own autonomy as an ability construct: we see her arguing with Tanizaki and defying his instruction, possessing talent and knowledge that Tanizaki does not have, and making decisions independent of Tanizaki’s will. For all intents and purposes, Naomi is no different than a human being.

Of course, whether or not this theory will prove correct is a different matter. It should be noted that one variation of this theory speculates that Naomi did exist as a real person, but died in middle school. Unable to cope with the loss, Tanizaki unconsciously created an illusion in her image. This idea is reminiscent of A Portrait of Shunkin (1933), where it is said that in the years after Sasuke’s mistress and lover passed away, “he created a Shunkin quite remote from the actual woman, yet more and more vivid in his mind.” The character Sasuke was said to exaggerate his mistress’ talents to the point that his accounts of her were unreliable, and her passing contributed to his over imagination of her likeliness.

Secret Relationships

Another theory I have seen circulating the fandom is that Naomi and Tanizaki lied about their relationship, telling others that they are siblings in order to cover up their romance. In Naomi (1925), a similar ruse is hatched by the character Naomi, who goes behind her husband Joji’s back and sleeps with other men. Joji discovers this subterfuge from the character Hamada, who confesses, “I didn't know about you at all. Miss Naomi...said you were her cousin.” As such, Tanizaki and Naomi may similarly be lying about the nature of their relationship, which would be a nod to the original novel.

Of course, though I am partial to this theory, since I would be sad if Naomi turned out to be an illusion, I cannot with any confidence claim that it is more likely than the other theory I mentioned regarding her, or any other theories that might be circulating.

Return from the West

Moving on from theories involving Naomi, evidence that supports the theory that Tanizaki will change allegiances from the Armed Detective Agency to the Port Mafia can also be found with his real life counterpart. As I touched on a bit before, Tanizaki-sensei wrote about and was influenced by Western culture and traditions. However, after Tanizaki-sensei moved from Yokohama to the Kansai region in 1926, his fascination dwindled, and he completed works such as Some Prefer Nettles (1929), which “[presented] subtly and effectively the great transformation in Tanizaki's life from a worshiper of the West to a believer in the value of the Japanese heritage” as explained by Donald Keene in “Five Modern Japanese Novelists”.

One such work that compared Western and Japanese culture is “In Praise of Shadows” (1933), which associated shadows with traditional Japanese aesthetics, and light with the West. In the essay, he writes “If light is scarce then light is scarce; we will immerse ourselves in the darkness and there discover its own particular beauty.” In Bungou Stray Dogs, darkness and shadows are associated with the Port Mafia, while the light is associated with living morally upright. As such, Tanizaki-sensei’s shift from his fascination with the West (the light) to finding beauty in the darkness (Japanese traditions) could be paralleled in his fictional counterpart switching sides as well.

Moreover, although I am far from informed enough to speak confidently on this subject, I’d be amiss not to mention this meta written by bsd-bibliophile, which explains how the Port Mafia authors were faithful to the styles of traditional Japanese literature, whereas Armed Detective Agency authors were influenced by Western writing. Coincidentally, or perhaps intentionally, the comparison of Japanese versus Western traditions is the subject matter of “In Praise of Shadows” (1933), as I explained above; it would be a very clever reference to Tanizaki-sensei’s shifting interest if the theory that Tanizaki will switch sides ends up being correct.

In Conclusion

Despite knowing very little of Tanizaki’s backstory, and having limited on screen appearances of him in the story, much of what is established about Tanizaki can be traced back to his real life counterpart. We can also attempt to reverse engineer the character Tanizaki by making conjectures about his backstory and future character development based on what we know about Tanizaki-sensei. The theories that Naomi is an illusion, Tanizaki and Naomi are not real siblings, and that Tanizaki will switch sides are all supported by themes, motifs, and narratives that frequently appeared in Tanizaki-sensei’s writing. As such, I am very excited to see which theories will prove true, and how Asagiri-sensei will execute them in Bungou Stray Dogs going forward.

credits: bsd-bibliophile is a great resource for PDFs and ePubs of the works mentioned here, manga caps were scanned and translated by Easy Going Scans or Dazai Scans, highlighted passage in second visual is from the official Light Novel 3, left image in third visual is the first edition cover of Naomi novel

#bsd#bungou stray dogs#bsd naomi#bsd tanizaki#tanizaki junichirou#tanizaki naomi#bsd theory#bsd meta#bsd analysis#min i'll never write an essay of my own free will lu#clown emoji#i think i should get an extra lit credit just for writing this

354 notes

·

View notes

Text

the unofficial ultimate bungo stray dogs reading list

this is mainly for myself bc i rly do want to read most if not all of these and i'm sure it's already been done by someone somewhere. but, i thought why not post it lmao; most if not all of these can be found on anna's archive, z-library, or project gutenberg! (also, consider buying from your local bookstore!) for those that are a bit harder to find, i've included links, though some are from j-stor and would require login to access.

detective agency:

osamu dazai:

no longer human (novel)

the setting sun (novel)

nakajima atsushi:

the moon over the mountain: stories (short story collection)

light, wind and dreams (short story)

fukuzawa yukichi:

an encouragement of learning (17 volume collections of writings)

all the countries of the world, for children written in verse (textbook)

yosano akiko:

kimi shinitamou koto nakare (poem)

midaregami (poetry collection)

edogawa ranpo:

the boy detectives club (book series)

japanese tales of mystery and imagination (short story collection)

the early cases of akechi kogoro (novel)

kunikida doppo:

river mist and other stories (short story collection)

izumi kyouka:

demon lake (play)

spirits of another sort: the plays of izumi kyoka (play collection)

tanizaki junichirou:

the makioka sisters (novel)

the red roof and other stories (short story collection)

miyazawa kenji:

ame ni mo makezu; be not defeated by the rain (poem)

night on the galactic railroad (novel)

strong in the rain (poetry collection)

port mafia:

mori ougai:

vita sexualis (novel)

the dancing girl (novel)

nakahara chuuya:

poems of nakahara chuya (poetry collection)

akutagawa ryuunosuke:

rashoumon (short story)

the spider's thread (short story)

rashoumon and other stories (short story collection)

ozaki kyouyou:

the gold demon (novel)

higuchi ichiyou:

in the shade of spring leaves (biography and short stories)

hirotsu ryuurou:

falling camellia (novel)

tachihara michizou:

in mourning for the summer (poem)

midwinter momento (poem)

from the country of eight islands: an anthology of japanese poetry (poetry collection)

kajii motojirou:

lemon (short story)

yumeno kyuusaku:

dogra magra (novel)

oda sakunosuke:

flawless/immaculate (short story)

sakaguchi ango:

darakuron (essay)

the guild:

f. scott fitzgerald:

the great gatsby (novel)

the beautiful and the damned (novel)

edgar allen poe:

the raven (poem)

the black cat (short story)

the murders in the rue morgue (short story)

herman melville:

moby dick (novel)

h.p. lovecraft:

the call of cthulhu (short story)

the shadow out of time (novella)

john steinbeck:

the grapes of wrath (novel)

of mice and men (novel)

lucy maud montgomery:

anne of green gables (novel)

the blue castle (novel)

chronicles of avonlea (short story collection)

louisa may alcott:

little women (novel)

the brownie and the princess (short story collection)

margaret mitchell:

gone with the wind (novel)

mark twain:

the adventures of tom sawyer (novel)

adventures of huckleberry finn (novel)

nathaniel hawthorn:

the scarlet letter (novel)

rats in the house of the dead:

fyodor dostoevsky:

crime and punishment (novel)

the brothers karamozov (novel)

notes from the underground (short story collection)

alexander pushkin:

eugene onegin (novel)

a feast in time of plague (play)

ivan goncharov:

the precipice (novel)

oguri mushitarou:

the perfect crime (novel)

decay of the angel:

fukuchi ouchi:

the mirror lion, a spring diversion (kabuki play)

bram stoker:

dracula (novel)

dracula's guest and other weird stories (short story collection)

nikolai gogol:

the overcoat (short story)

dead souls (novel)

hunting dogs: (i must caveat here that the hunting dogs are named after much more comparatively obscure jpn writers/playwrights so i was unable to find a lot of the specific pieces actually mentioned; but i still wanted to include them on the list because well -- it wouldn't be a bsd list without them)

okura teruko:

gasp of the soul (short story; i wasn't able to find an english translation)

devil woman (short story)

jouno saigiku:

priceless tears (kabuki play; no translation but at least we have a summary)

suehiro tetchou:

setchuubai/a political novel: plum blossoms in snow (novel)

division for unusual powers:

taneda santouka:

the santoka: versions by scott watson (poetry collection)

tsujimura mizuki:

lonely castle in the mirror (novel)

yesterday's shadow tag (short story collection; i was unable to find a translation)

order of the clock tower:

agatha christie:

and then there were none (novel)

murder on the orient express (novel)

she is the best selling fiction writer of all time there's too much to list here

mimic:

andre gide:

strait is the gate (novel)

trascendents:

arthur rimbaud:

illuminations (poetry collection)

the drunken boat (poem)

a season in hell (prose poem)

johann von goethe:

faust

the sorrows of young werther

paul verlaine:

clair de lune (poem, yes it did inspire the debussy piece, yes)

poems under saturn (poetry collection)

victor hugo:

the hunchback of notre-dame (novel)

les miserables (novel)

william shakespeare:

romeo and juliet (play)

a midsummer nights' dream (play)

sonnets (poetry collection)

the seven traitors:

jules verne:

around the world in 80 days (novel)

journey to the center of the earth (novel)

twenty thousand leagues under the seas (novel)

other:

natsume souseki:

i am a cat (novel)

kokoro (novel)

botchan (novel)

h.g. wells:

the time machine (novella)

the invisible man (novel)

the war of the worlds (novel)

shibusawa tatsuhiko:

the travels of prince takaoka (novel; unable to find translation)

dr. mary wollstonecraft godwin shelley

frankenstein (novel)

#bungo stray dogs#bsd#literature#dark academia#reading list#academia#i'm sure there's people i've missed but i did my best LOL#this also really throws into a stark contrast how relatively un-worldly american literary curriculums really are#obviously; it makes vague sense to focus american literary schooling on the western 'canon' bc so much of the english language#is influenced by it and the 'culture' is more touched by it but HOLY SHIT does it just... astound me#how uneducated i am on even east asian literature (from wheremst i technically hail!!!)#i know like.... maybe 3?? 4??? chinese writers off cuff???#like the only reason i even know anything about jpn literature is i got my minor in jpn so i read some stuff but WOWWWWW there's a wORLD.#the fact that i knew not a SINGLE work by most of these jpn writers but as soon as we got to the guild members#i didn't even have to fucking google/wiki -- i just KNEW off the top of my head#kinda fucked up tbh;;;;#anyway this list is massive but i think at least dipping my foot into some of the poems/short stories will be fun

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

i miss my 2021 hot girl summer of binge reading works of literature referenced in bsd

#i'm still working through my bsd reading list#but i read most of the short stories first so i kind of lost the momentum after that#i've been meaning to read the makioka sisters next so maybe i will finally do that this summer#technically i'm also reading moby dick but. i'm slow with that one#little women and the precipe have also been on hold for a while

12 notes

·

View notes